Optical Properties of Nitrogen-Substituted Strontium Titanate Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

3. Results and Discussion

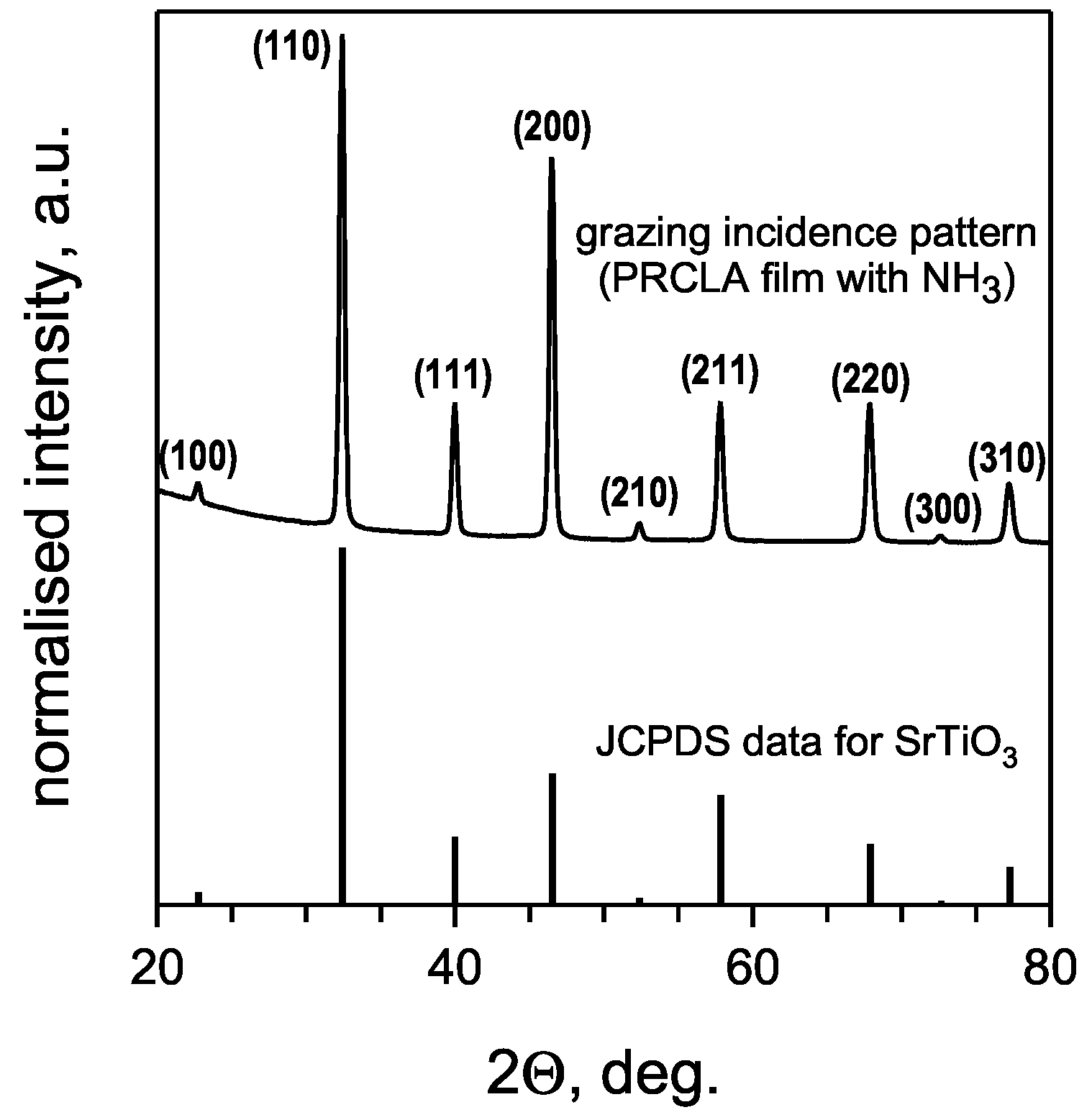

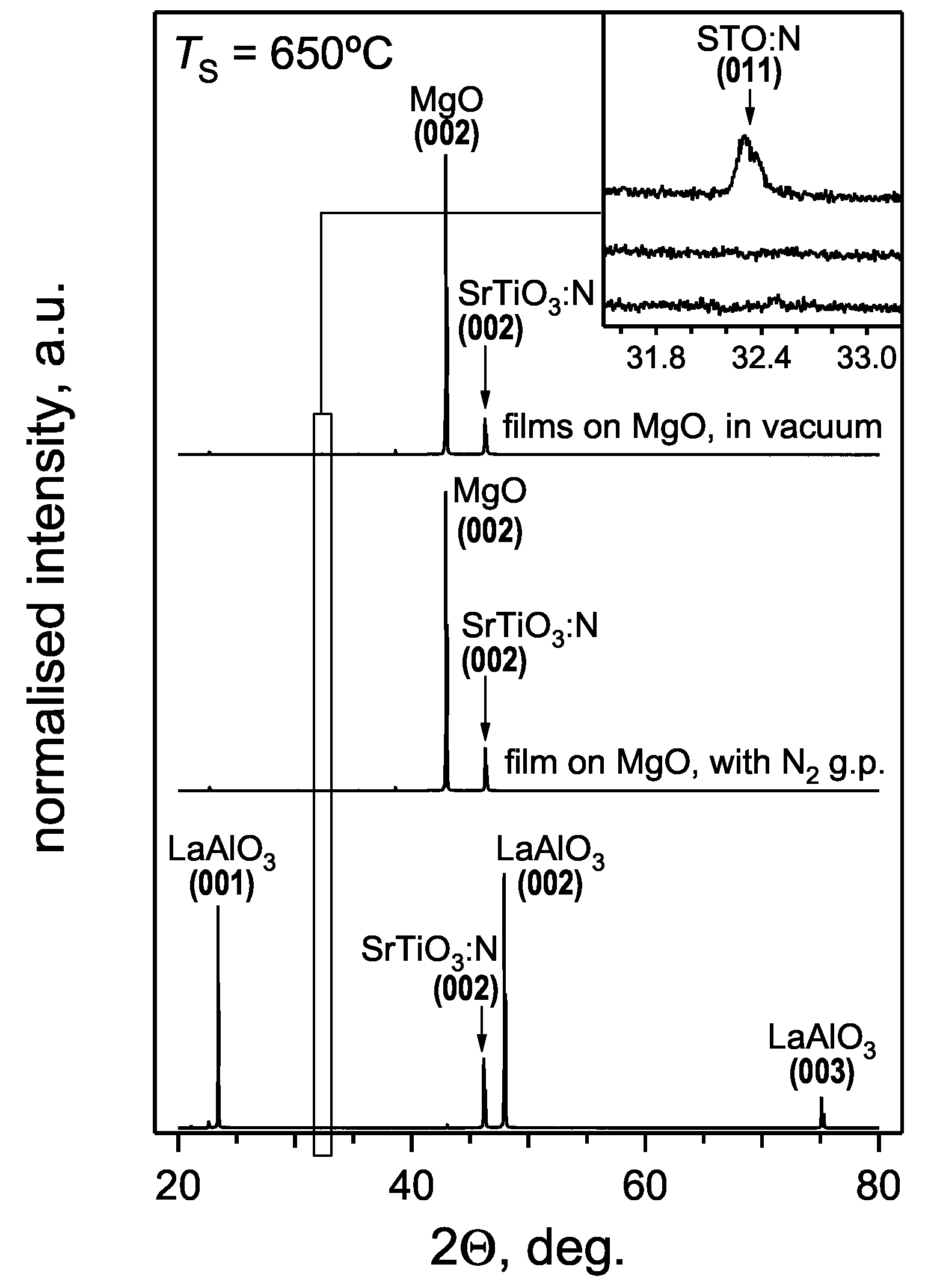

3.1. Crystal structure of SrTiO3:N thin films

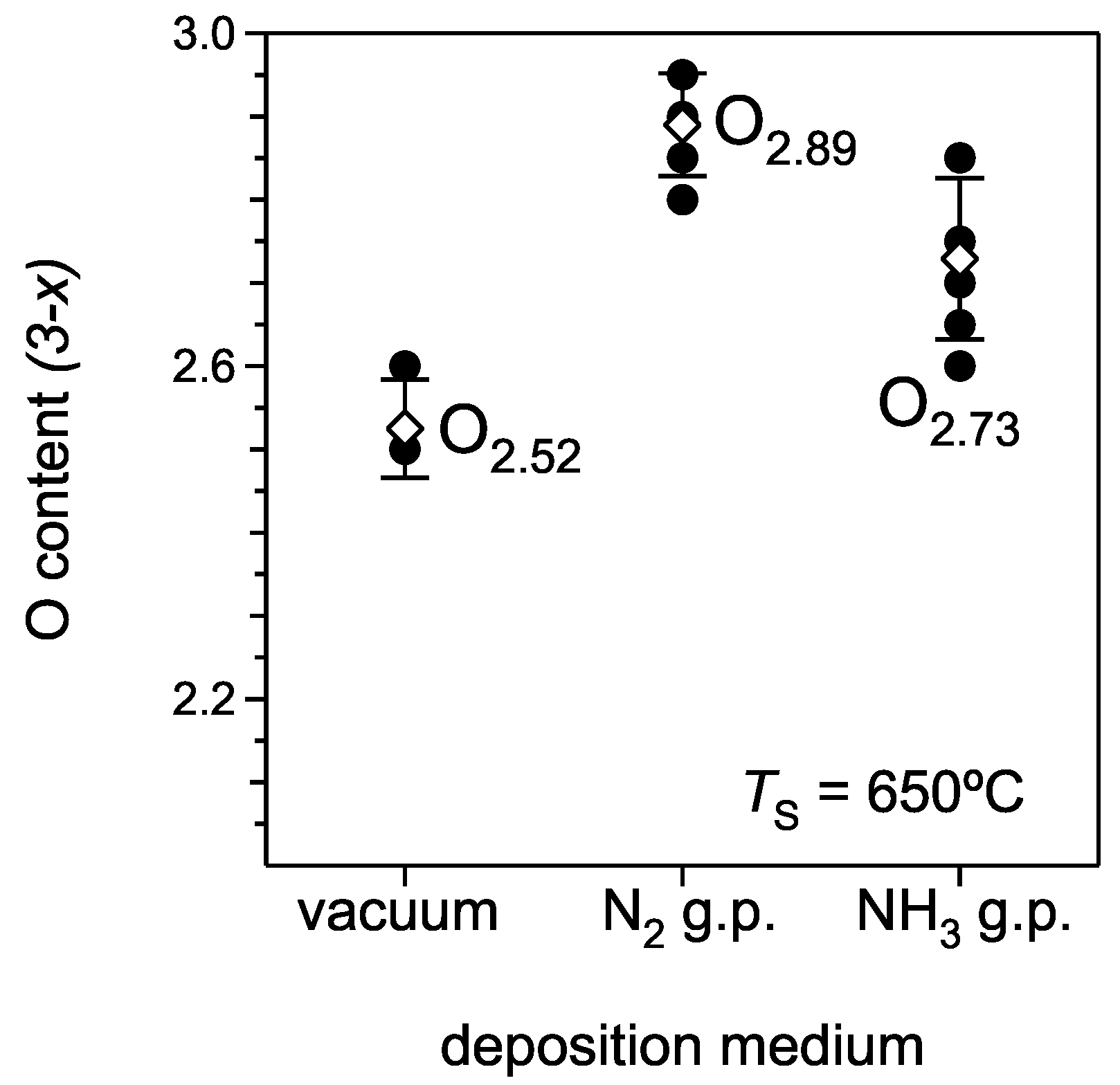

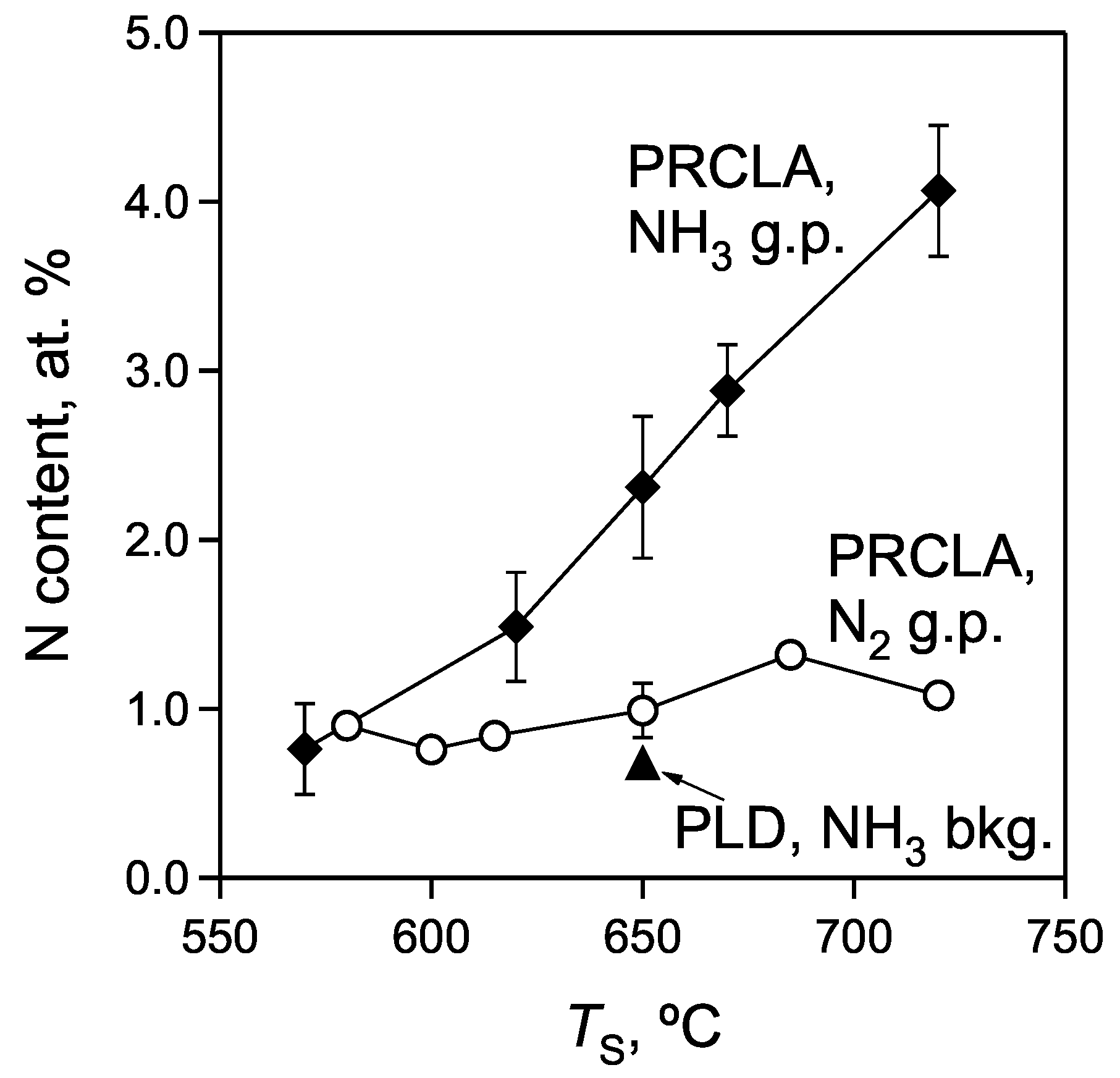

3.2. Chemical composition of SrTiO3:N thin films

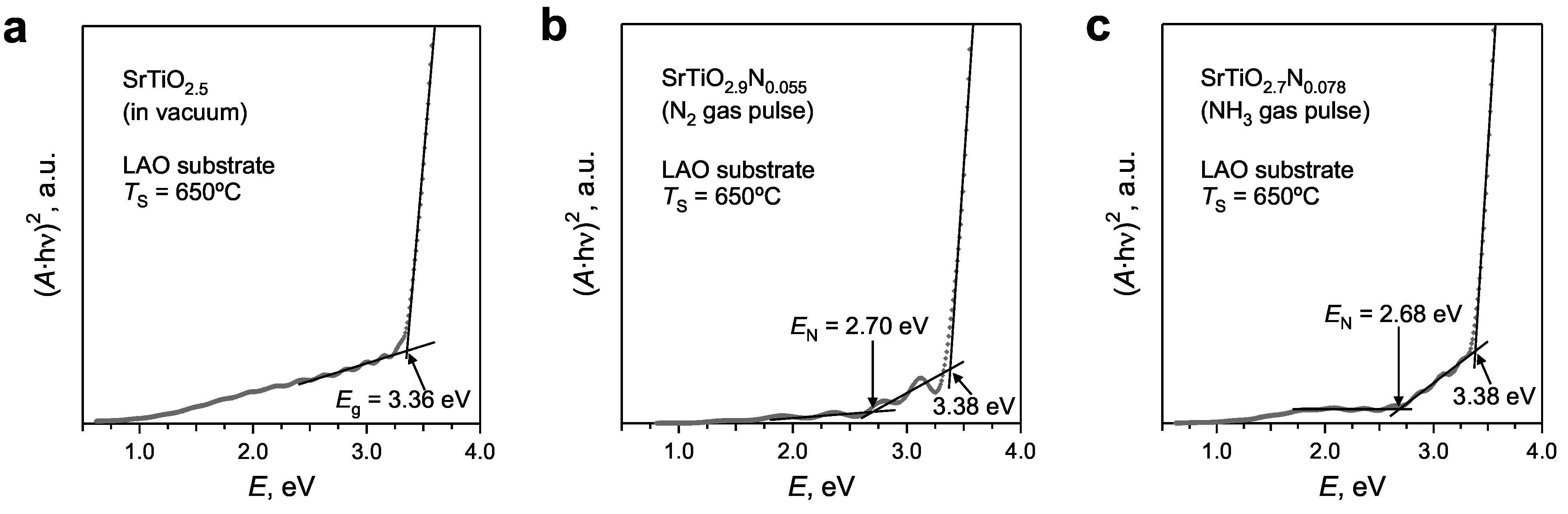

| Deposition Conditions | Average Film Composition | Eg ± 0.05 [eV] | EN ± 0.10 [eV] |

|---|---|---|---|

| conventional PLD, NH3 background | Sr0.98Ti1.02O2.9N0.032 | ||

| PRCLA, under vacuum | Sr0.97Ti1.03O2.52 | 3.36 | |

| PRCLA, with N2 gas pulse | Sr0.98Ti1.02O2.89N0.049 | 3.38 | 2.70 |

| PRCLA, with NH3 gas pulse | Sr0.95Ti1.05O2.73N0.112 | 3.38 | 2.68 |

- Plasma species in a laser plume have a much higher kinetic energy with a deposition in vacuum causing re-sputtering of light elements, such as O, from the surface of the growing film. During the deposition with the gas pulse, the ablated species are slowed down considerably and are not energetic enough to cause a significant re-sputtering [28,29,30]. As a result the oxygen content in a film becomes higher.

- A minor O2 impurity in the used gases (~0.01%) and the very high affinity of the growing film to oxygen species become important for the final oxygen content in films. The average oxygen stoichiometry factors for films deposited with N2 and NH3 gas pulses are 2.89 ± 0.06 and 2.73 ± 0.10, respectively.

- Different dissociation energy of N2 and NH3 molecules. Active atomic nitrogen is probably the most important species for the formation of oxynitrides [31]. During the deposition of thin oxynitride films by PLD these species are mainly produced by the dissociation of the gas pulse and background gas molecules via collisions with the high energetic ablated species from the target. The N2 molecule is thermodynamically very stable and has a dissociation energy of 945 kJ·mol‑1 (~9.8 eV) [32], which is considerably higher compared to the average dissociation energy for one N‑H bond in an NH3 molecule of 391 kJ·mol‑1 (~4.1 eV) [32]. Typical ion energies in PRCLA (close to the target) vary in the range of 5‑15 eV [33]. Thus, it is possible to disproportionate both nitrogen and ammonia molecules and produce active N‑containing species in the PRCLA process via collisions of the ablation plume species with the gas pulse molecules. However, smaller chemical bond energies and the possibility of a consecutive detachment of hydrogen atoms in NH3 makes this process more likely if compared to N2. This results in the higher concentration of atomic N species in the plasma, and in a larger nitrogen content in films grown with the NH3 gas pulse.

- Reducing properties of ammonia and related reaction products. As already pointed out, they can capture the oxygen species in the plasma and at the surface of the growing film, thereby reducing the oxygen content in films. This enhances the number of vacant anionic sites in the crystal lattice available for nitrogen incorporation.

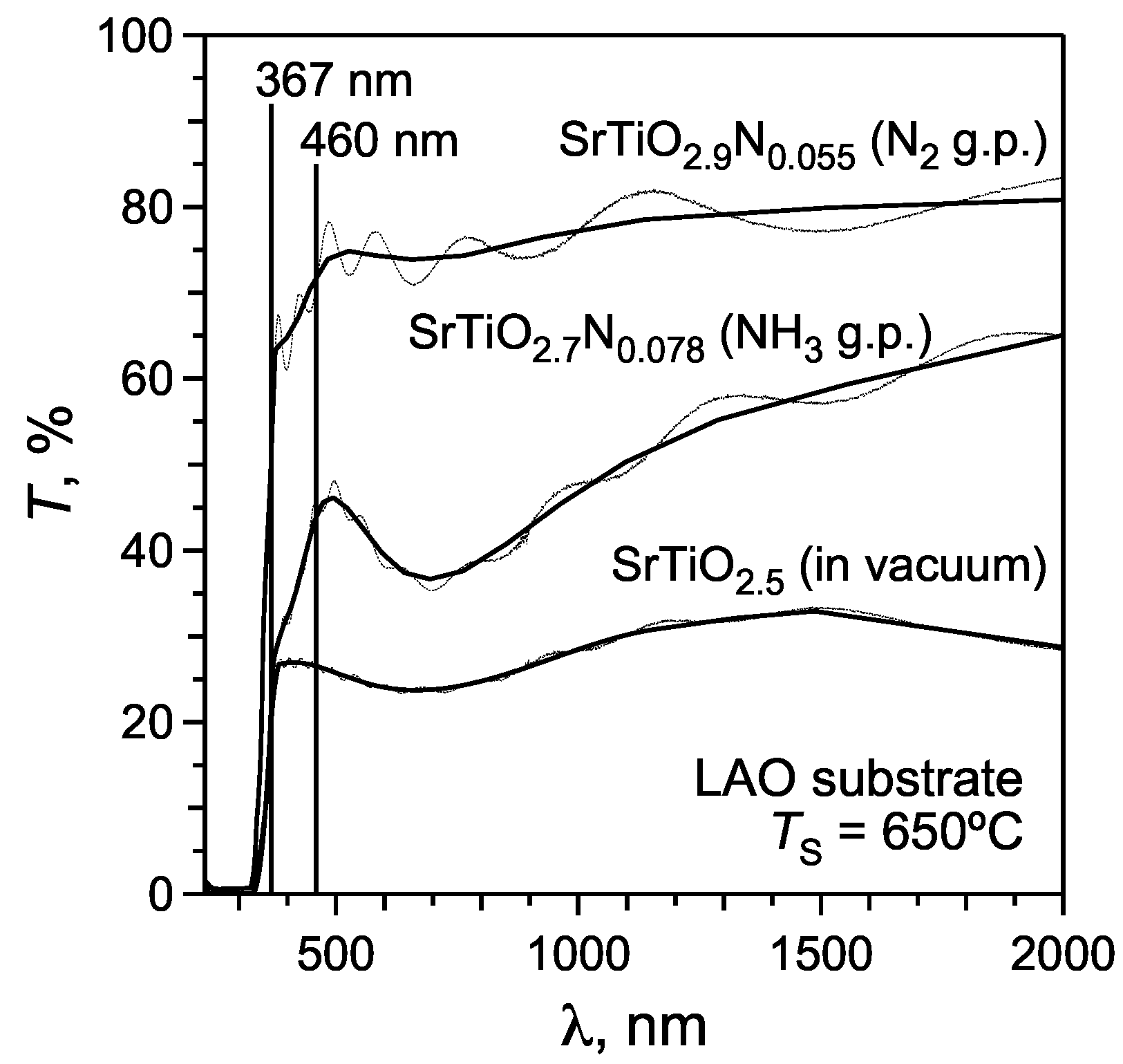

3.3. Optical properties of SrTiO3:N thin films

- Absorption of IR and visible light in a wavelength range of 460‑2,000 nm, which corresponds to photon energies of ~0.6‑2.7 eV. Absorption of these low‑energetic photons is attributed to the electronic transitions within the conduction band of reduced SrTiO3 [35]. Therefore, films with larger anionic deficiencies (i.e., with higher Ti3+ contents) reveal stronger absorption and lower transmittance (T) in this wavelength region, i.e., T (film in vacuum) < T (film with NH3 gas pulse) < T (film with N2 gas pulse).

- A broad absorption band at wavelengths below 367 nm (3.38 eV) is attributed to the band gap of SrTiO3 and occurs through excitation of the valence band electrons to the conduction band. The large electron density in the valence band results in an almost complete absorption of UV light in this wavelength region.

- The absorption shoulder between 367 and 460 nm is a specific feature of N‑substituted SrTiO3 which is not observed in stoichiometric or reduced strontium titanate [13]. This absorption shoulder is attributed to the electron transitions from the localized populated N(2p) states to the conduction band.

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Mitchell, R.H. Perovskites. Modern and Ancient; Almaz Press: Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.; Guo, R.; Bhalla, A.S. Perovskite Oxides for Electronic, Energy Conversion, and Energy Efficiency Applications; The American Ceramic Society: Westerville, OH, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Twu, J.; Gallagher, P.K. Properties and Applications of Perovskite-Type Oxides; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tessier, F.; Marchand, R. Ternary and higher order rare-earth nitride materials: Synthesis and characterization of ionic-covalent oxynitride powders. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 171, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevire, F.; Tessier, F.; Marchand, R. Optical properties of the perovskite solid solution LaTiO2N-ATiO3 (A = Sr, Ba). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 6, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Letschert, H.P. Inorganic yellow-red pigments without toxic metals. Nature 2000, 404, 980–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekshmi, I.C.; Gayen, A.; Hegde, M.S. The effect of strain on nonlinear temperature dependence of resistivity in SrMoO3 and SrMoO3-xNx films. Mater. Res. Bull. 2005, 40, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logvinovich, D.; Aguiar, R.; Robert, R.; Trottmann, M.; Ebbinghaus, S.G.; Reller, A.; Weidenkaff, A. Synthesis, Mo-valence state, thermal stability and thermoelectric properties of SrMoO3-xNx (x > 1) oxynitride perovskites. J. Solid State Chem. 2007, 180, 2649–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logvinovich, D.; Börger, A.; Döbeli, M.; Ebbinghaus, S.G.; Reller, A.; Weidenkaff, A. Synthesis and physical chemical properties of Ca-substituted LaTiO2N. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2007, 35, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, R.; Tessier, F.; Le Sauze, A.; Diot, N. Typical features of nitrogen in nitride-type compounds. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 3, 1143–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuu, D.S.; Horng, R.H.; Liao, F.C.; Lin, C.C. Nitridation of (Ba,Sr)TiO3 films in an inductively coupled plasma. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2001, 280, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasita, D.; Takata, T.; Hara, M.; Kondo, J.N.; Domen, K. Recent progress of visible-light-driven heterogeneous photocatalysts for overall water splitting. Solid State Ionics 2004, 172, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, M.; Takashio, M.; Tobimatsu, H. Photocatalytic activity of SrTiO3 codoped with nitrogen and lanthanum under visible light illumination. Langmuir 2004, 20, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marozau, I.; Shkabko, A.; Dinescu, G.; Dobeli, M.; Lippert, T.; Logvinovich, D.; Mallepell, M.; Schneider, C.W.; Weidenkaff, A.; Wokaun, A. Pulsed laser deposition and characterization of nitrogen-substituted SrTiO3 thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, M.J.; Conder, K.; Dobeli, M.; Lippert, T.; Willmott, P.R.; Wokaun, A. Pulsed reactive crossed beam laser ablation of La0.6Ca0.4CoO3 using 18O. Where does the oxygen come from? Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 4642–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, P.R.; Timm, R.; Huber, J.R. Reactive crossed beam scattering of a Ti plasma and a N2 pulse in a novel laser ablation method. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 82, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marozau, I.; Döbeli, M.; Lippert, T.; Logvinovich, D.; Mallepell, M.; Shkabko, A.; Weidenkaff, A.; Wokaun, A. One-step preparation of N-doped strontium titanate films by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 2007, 89, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.K.; Mayer, J.W.; Nicolet, M.A. Backscattering Spectrometry; Academic Press: New York/London, USA/UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Döbeli, M. Characterization of oxide films by MeV ion beam techniques. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 264010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, H.W.; Barnes, P.W.; Auer, B.M.; Woodward, P.M. Investigations of the electronic structure of d0 transition metal oxides belonging to the perovskite family. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 175, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, T.; Lippmaa, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Meguro, S.; Koinuma, H. Improved stoichiometry and misfit control in perovskite thin film formation at a critical fluence by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 241919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkabko, A.; Aguirre, M.H.; Marozau, I.; Doebeli, M.; Mallepellc, M.; Lippert, T.; Weidenkaff, A. Characterization and properties of microwave plasma-treated SrTiO3. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 115, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, V.E.; Dresselhaus, G.; Zeiger, H.J. Surface defects and electronic structure of SrTiO3 surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 1978, 17, 4908–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canulescu, S.; Lippert, T.; Grimmer, H.; Wokaun, A.; Robert, R.; Logvinovich, D.; Weidenkaff, A.; Doebeli, A. Structural characterization and magnetoresistance of manganates thin films and Fe-doped manganates thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 4599–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canulescu, S.; Dinescu, G.; Epurescu, G.; Matei, D. G.; Grigoriu, C.; Craciun, F.; Verardi, P.; Dinescu, M. Properties of BaTiO3 thin films deposited by radiofrequency beam discharge assisted pulsed laser deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2004, 109, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmehl, A.; Lichtenberg, F.; Bielefeldt, H.; Mannhart, J.; Schlom, D.G. Transport properties of LaTiO3+x films and heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 3077–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Casero, R.; Perriere, J.; Gutierrez-Llorente, A.; Defourneau, D.; Millon, E.; Seiler, W.; Soriano, L. Thin films of oxygen deficient perovskite phases. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 165317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, M.J. Perovskite Thin Films Deposited by Pulsed Reactive Crossed Beam Laser Ablation as Model Systems for Electrochemical Applications; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro, M.J.; Clerc, C.; Lippert, T.; Müller, S.; Willmott, P.R.; Weidenkaff, A.; Wokaun, A. Analysis of the plasma produced by pulsed reactive crossed-beam laser ablation of La0.6Ca0.4CoO3. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 208–209, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, P.R.; Huber, J.R. Pulsed laser vaporization and deposition. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000, 72, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, A.; Hendry, A. Formation of barium-tantalum oxynitrides. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 4686–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleman, A.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. Lehrbuch der anorganischen Chemie; de Gruyter: Berlin, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Canulescu, S.; Lippert, T.; Wokaun, A. Mass and kinetic energy distribution of the species generated by laser ablation of La0.6Ca0.4MnO3. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 2008, 93, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkabko, A.; Aguirre, M.H.; Marozau, I.; Lippert, T.; Weidenkaff, A. Resistance switching at the Al/SrTiO3−xNy anode interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 212102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Destry, J.; Brebner, J.L. Optical-absorption and transport in semiconducting SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 1975, 11, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, T.; Tanaka, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Yogo, T. Influence of the transition-metal doping on conductivity of a BaCeO3-based protonic conductor. Solid State Ionics 2005, 176, 2945–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, H.W. Optical transmission of heat-treated strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. 1959, 113, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.J.; Gao, X.Y.; Wee, A.T.S.; Ong, C.K.; Huan, C.H.A. Thermal stability of nitrogen-doped SrTiO3 films: Electronic and optical properties studies. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 5. [Google Scholar]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Marozau, I.; Shkabko, A.; Döbeli, M.; Lippert, T.; Logvinovich, D.; Mallepell, M.; Schneider, C.W.; Weidenkaff, A.; Wokaun, A. Optical Properties of Nitrogen-Substituted Strontium Titanate Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition. Materials 2009, 2, 1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma2031388

Marozau I, Shkabko A, Döbeli M, Lippert T, Logvinovich D, Mallepell M, Schneider CW, Weidenkaff A, Wokaun A. Optical Properties of Nitrogen-Substituted Strontium Titanate Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition. Materials. 2009; 2(3):1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma2031388

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarozau, Ivan, Andrey Shkabko, Max Döbeli, Thomas Lippert, Dimitri Logvinovich, Marc Mallepell, Christof W. Schneider, Anke Weidenkaff, and Alexander Wokaun. 2009. "Optical Properties of Nitrogen-Substituted Strontium Titanate Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed Laser Deposition" Materials 2, no. 3: 1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma2031388