Simulation of Granular Flows and Pile Formation in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin, and Experimental Verification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Description of Simulation

2.1. Granular Flows and Piles in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin

2.2. Air Flow in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin

3. Computational Domain, Conditions and Procedure

| Computational conditions. | Experimental conditions. | |

|---|---|---|

| Particle | Spherical glass beads | Spherical glass beads |

| Particle diameter, Dp | 200 μm | 201 μm |

| Standard deviation of Dp | 0 μm | 6 μm |

| Particle density, ρp | 2500 kg/m3 | 2490 kg/m3 |

| Initial particle bed height | 83.3 mm | 83.3 mm |

| Initial packing fraction, ρb/ρp | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Imaginary particle mass of SPH, m0 | 6.94 × 10−6 kg | – |

| Number of imaginary particles of SPH | 9000 | – |

| Initial distance between imaginary particle centers of SPH, hk | 1.67 mm | – |

| Computational cell sizes of air velocity, Δx = Δy = Δz | 1.25 mm | – |

| Number of computational cells of air velocity, Nx × Ny × Nz | 80 × 4 × 200 = 64,000 | – |

| Time Step, Δt | 2.0 × 10−6 s | – |

4. Experimental Apparatus

5. Results and Discussion

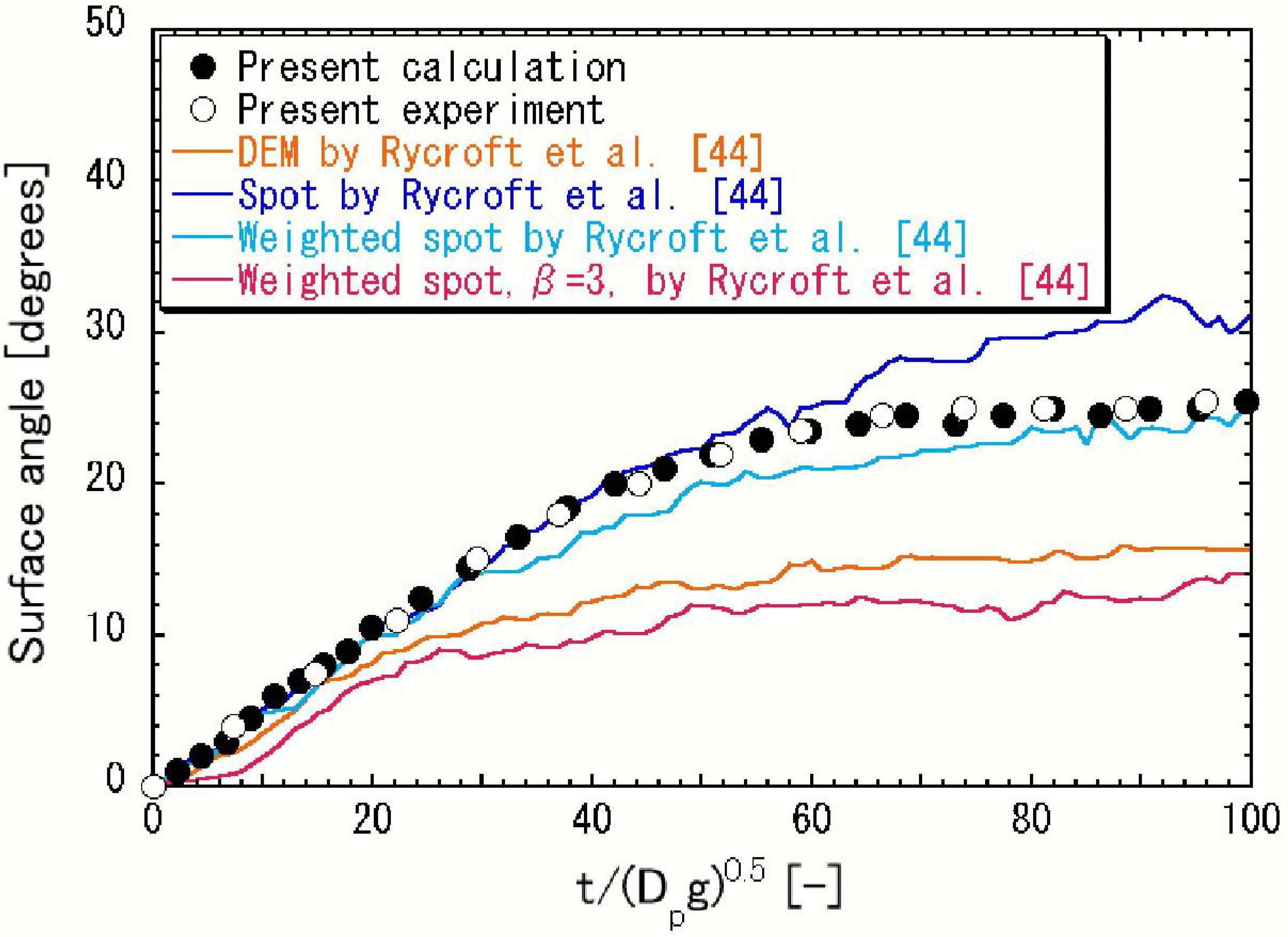

5.1. Granular Flows and Piles in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin

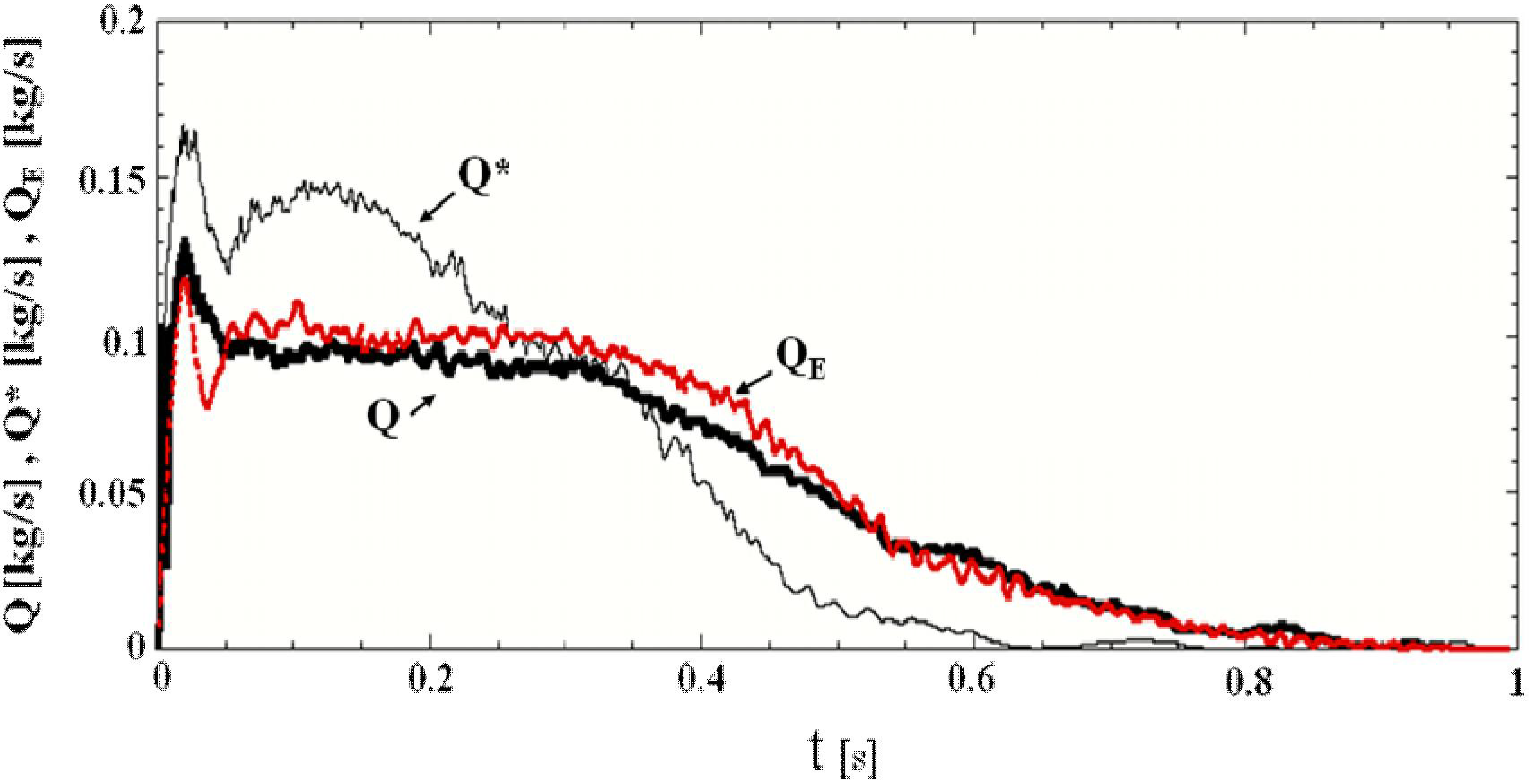

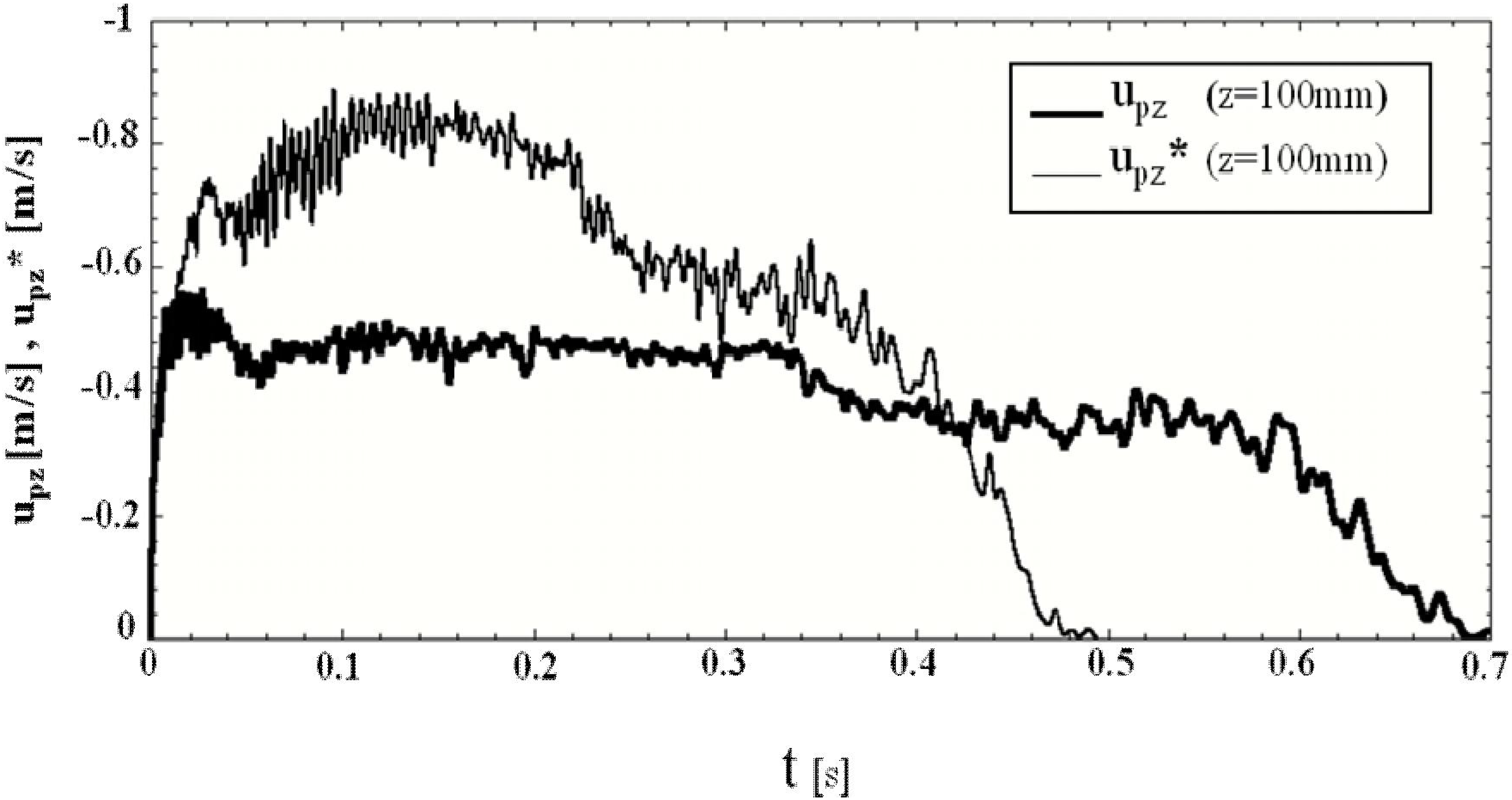

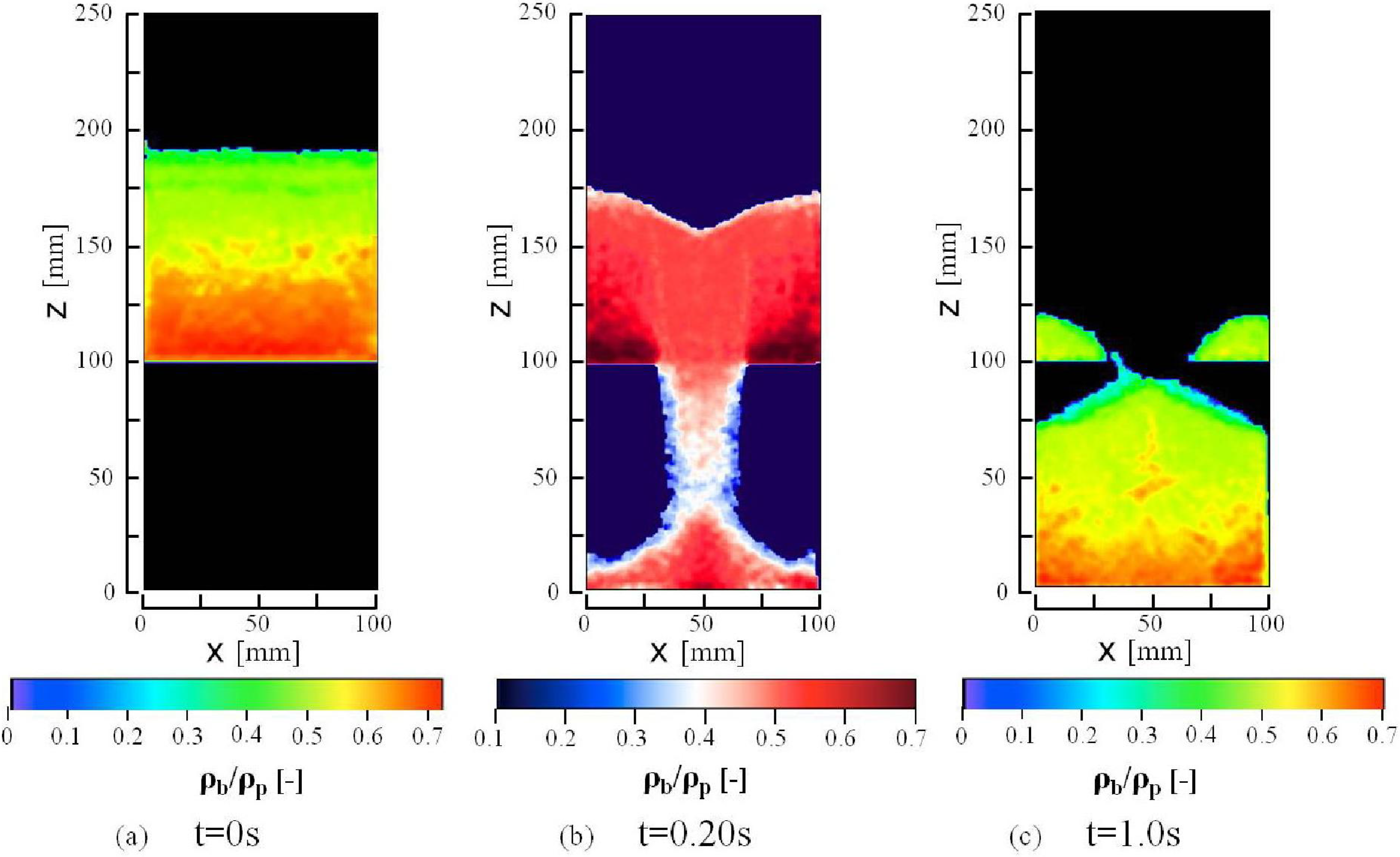

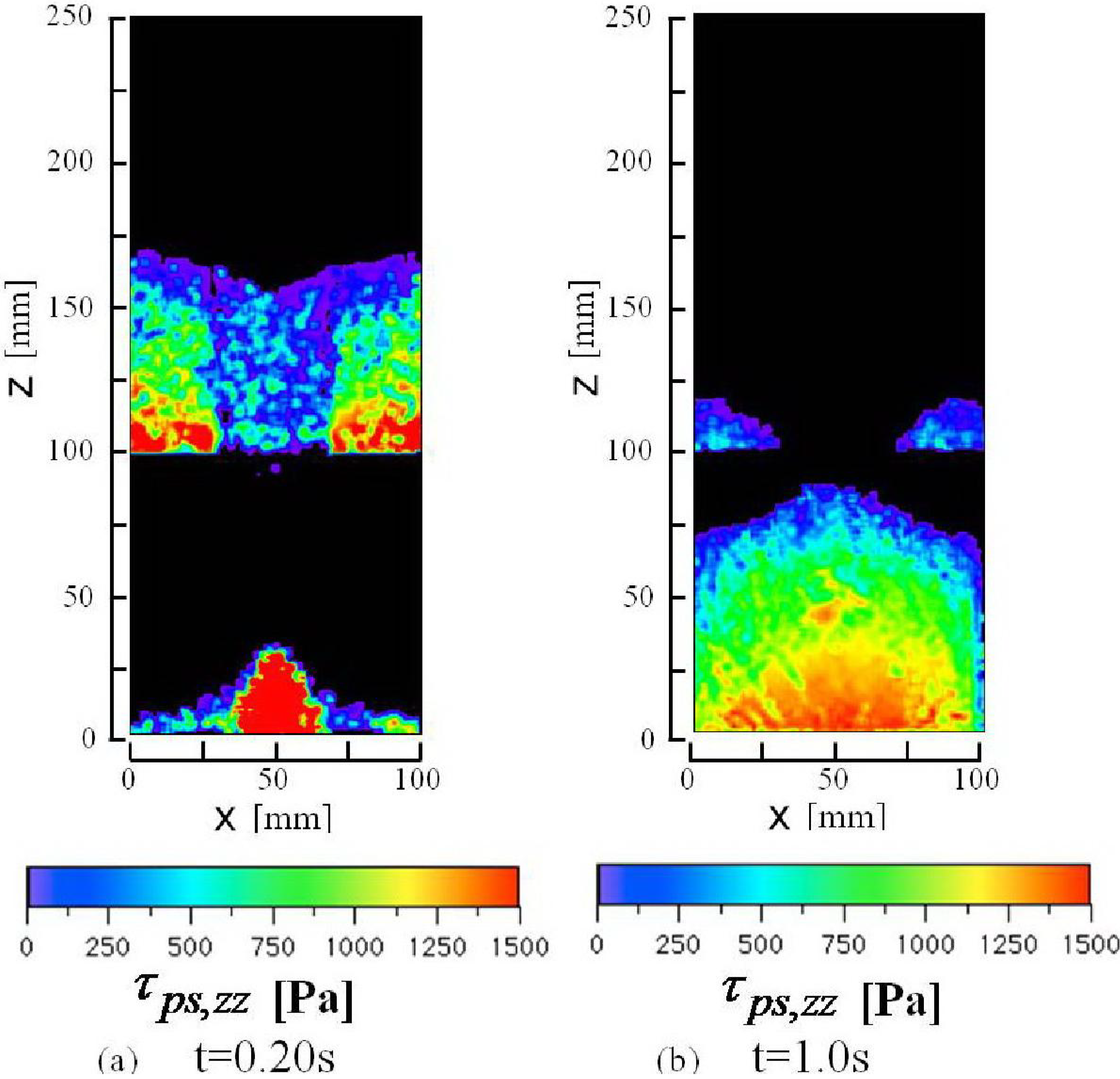

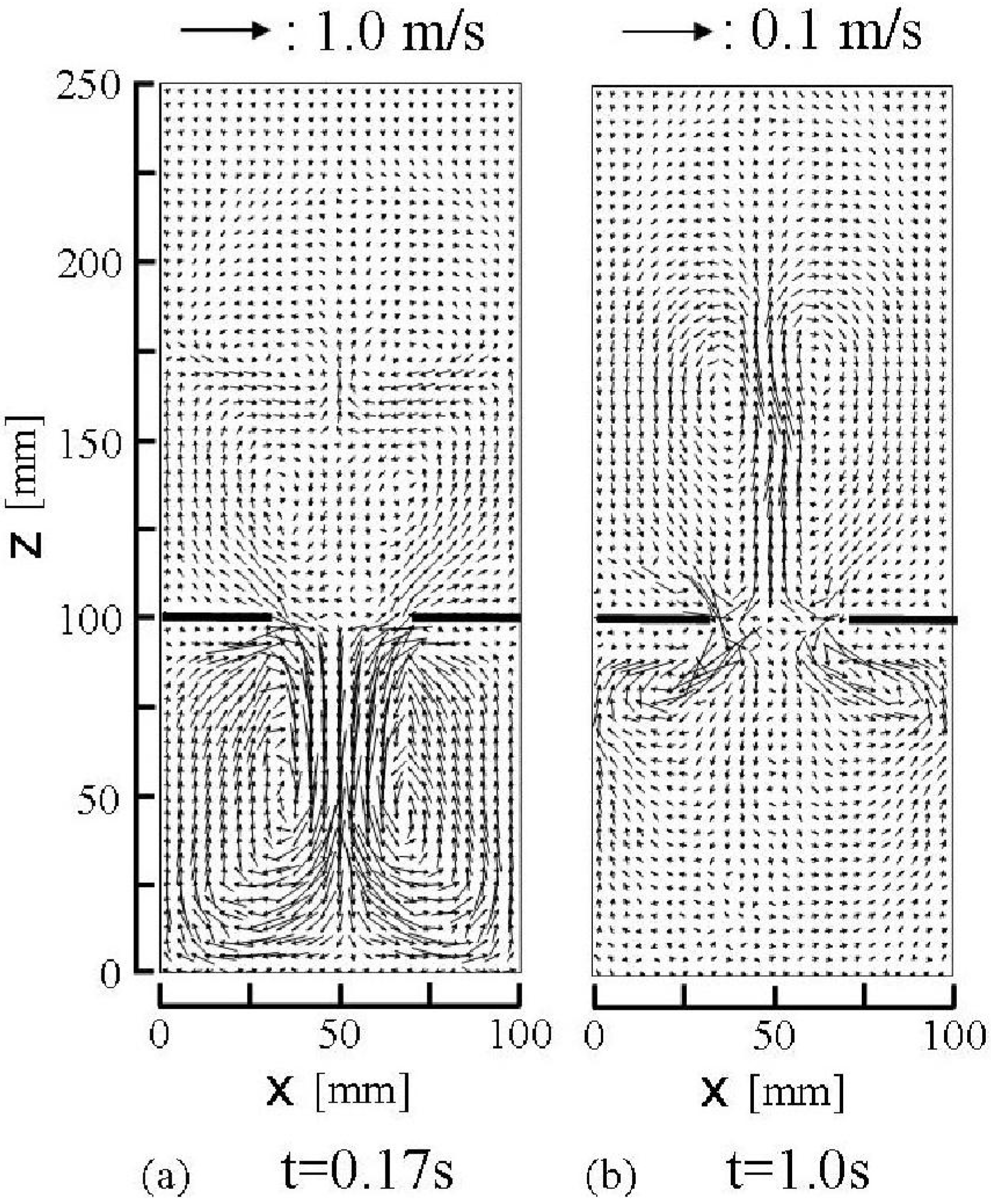

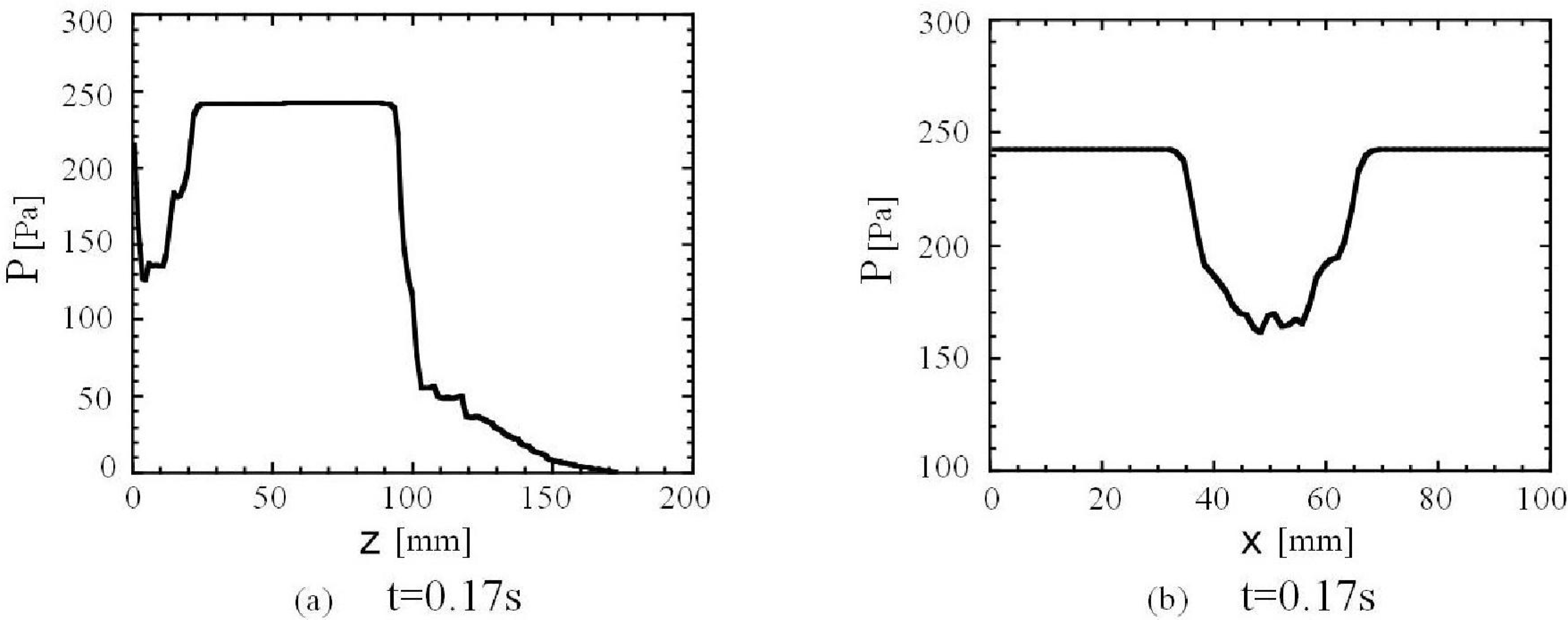

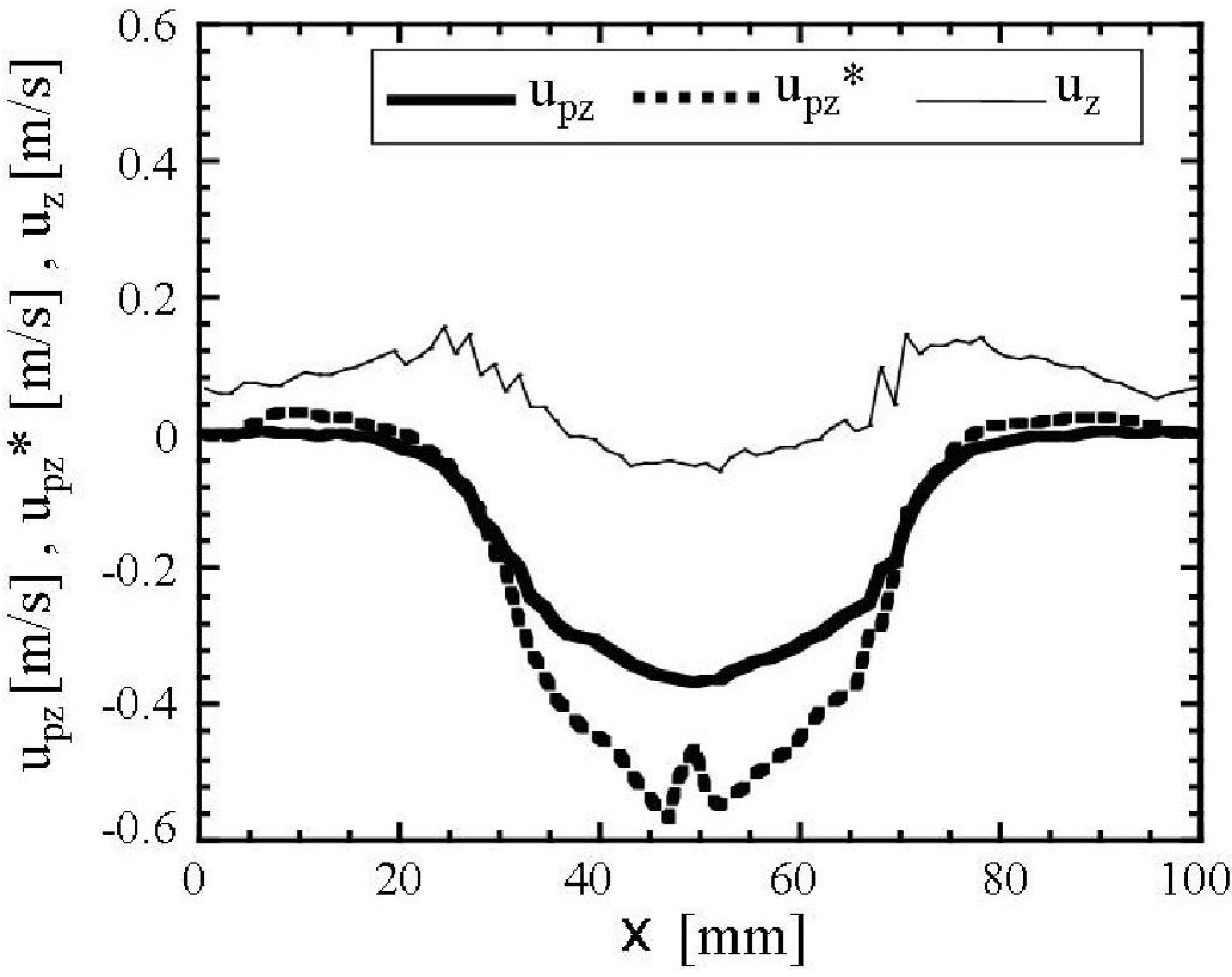

5.2. Effect of Air on Granular Flow in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1References

- Yuu, S.; Umekage, T. Constitutive relations and computer simulation of granular material. Adv. Powder Technol. 2008, 19, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranson, I.S.; Tsimring, L.S. Continuum description of avalanches in granular media. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 020301:1–020301:4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranson, I.S.; Tsimring, L.S. Continuum theory of partially fluidized granular flows. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 65, 061303:1–061303:20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrin, K.; Bazant, M.Z. Stochastic flow rule for granular materials. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 041301:1–041301:28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DorMohammadi, H.; Khoei, A.R. A three-invariant cap model with isotropic-kinematic hardening rule and associated plasticity for granular materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2008, 45, 631–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ooi, J.; Rotter, M.; Wang, Y. Numerical analysis of silo behavior using non-coaxial models. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedderman, R.M.; Tuzun, U. Kinematic model for the flow of granular materials. Powder Technol. 1979, 22, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.S.; Hsu, J.Y.; Lau, Y.D. The granular flow in a two-dimensional flat-bottomed hopper with eccentric discharge. Phys. A 2002, 308, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, A.; Ferjani, M. Revised model for plug/funnel flow in bins. Powder Technol. 2004, 141, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, P.; Guaita, M.; Ayuga, F. Analysis of dynamic discharge pressure in cylindrical slender silos with a flat bottom or with a hopper: Comparison with Eurocode 1. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 91, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Geotechnique 1979, 29, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, T.J.; Ebert, F. Three-dimensional discrete element simulations in hoppers and silos. Powder Technol. 2005, 158, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.P.; Yu, A.B.; Wu, Y.H. Numerical investigation of steady and unsteady state hopper flows. Powder Technol. 2006, 170, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H. Computer simulation of rapid granular flow through an orifice. J. Appl. Mech. 2007, 74, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Curtis, J.S.; Wassgren, C.R.; Hancock, B.C.; Ketterhagen, W.R. Predicting discharge dynamics from a rectangular hopper using the discrete element method (DEM). Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 5821–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruggel-Emden, H.; Rickelt, S.; Wirtz, S.; Scherer, V. A numerical study on the sensitivity of the discrete element method for hopper discharge. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2009, 131, 031211:1–031211:10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Binbo, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y. Multi-scale study of particle flow in silos. Adv. Powder Technol. 2009, 20, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterhagen, W.R.; Curtis, J.S.; Wassegren, C.R.; Kong, A.; Narayan, P.J.; Hancock, B.C. Granular segregation in discharging cylindrical hopper: A discrete element and experimental study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62, 6423–6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterhagen, W.R.; Curtis, J.S.; Wassgren, C.R.; Hancock, B.C. Modeling granular segregation in flow from quasi-three-dimensional wedge-shaped hoppers. Powder Technol. 2008, 179, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Curtis, J.S.; Wassgren, C.R.; Hancock, B.C.; Ketterhagen, W.R. Segregation of cohesive granular materials during discharge from a rectangular hopper. Granul. Matter 2010, 12, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balevicius, R.; Kacianauskas, R.; Mroz, Z.; Sielamowicz, I. Discrete-particle investigation of friction effect in filling and unsteady/steady discharge in three-dimensional wedge-shaped hopper. Powder Technol. 2008, 187, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzun, U.; Baxter, J.; Heyes, D.M. Analysis of the evolution of granular stress—Strain and voidage states based on DEM simulations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London A 2004, 362, 1931–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, M.; Shen, H.H.; Shen, H.T. The stress tensor in granular shear flows of uniform, deformable disks at high solids concentrations. J. Fluid Mech. 1990, 219, 81–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Shen, H.H. Internal parameters and regime map for soft polydispersed granular materials. J. Rheol. 2008, 52, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuu, S.; Umekage, T.; Mitsuiki, Y.; Koga, F. Constitutive relations based on Distinct Element Method results for granular materials and simulation of granular collapse and heap by smoothed particle hydrodynamics, and experimental verification. Adv. Powder Technol. 2008, 19, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuu, S.; Hayashi, A.; Waki, M.; Umekage, T. The stress-strain rate relationship for flowing coarse particle powder beds obtained by the 3-dimensional DEM and experiments. J. Soc. Powder Technol. Jpn. 1997, 34, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jop, P.; Forterre, Y.; Pouliquen, O. A constitutive law for dense granular flows. Nature 2006, 441, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Cruz, F.; Eman, S.; Prochnow, M.; Roux, J.N.; Chevoir, F. Rheophysics of dense granular materials: Discrete simulation of plane shear flows. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 72, 021309:1–021309:17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubliner, J. Plasticity Theory; Dover Publication: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sugino, T.; Yuu, S. Numerical analysis of fine powder flow using smoothed particle hydro-dynamics and experimental verification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002, 57, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.H.; Fukagawa, R.; Sako, K.; Ohno, S. Lagrangian meshfree particles method (SPH) for large deformation and failure flows of geomaterial using elastic-plastic soil constitutive model. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Mech. Geomech. 2008, 32, 1537–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutfraind, R.; Savage, S.B. Flow of fractured ice through wedge-shaped channels, smoothed particle hydrodynamics and discrete-element simulations. Mech. Mater. 1998, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, J.J. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1992, 30, 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuu, S.; Umekage, T.; Matsumoto, K. Numerical simulation of flow fields in two-dimensional fluidized bed using smoothed particle hydrodynamics based on stress strain relations obtained by discrete element method calculation and finite difference method, and experimental verification. Kagaku Kougaku Ronbunshu 2005, 31, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, J.J. Simulation free surface flows with SPH. J. Comput. Phys. 1994, 110, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuu, S.; Umekage, T. Numerical simulation of constitutive relationship between stress and strain of particulate matters. J. Soc. Powder Technol. 2005, 42, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuu, S.; Umekage, T.; Johno, Y. Numerical simulation of air and particle motions in bubbling fluidized bed of small particles. Powder Technol. 2000, 110, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, K.D.; Eaton, J.K. Particle response and turbulence modification in isotropic turbulence. Phys. Fluids. 1990, A2, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, C.; Sommerfeld, M.; Tsuji, Y. Multiphase Flows with Droplets and Particles; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 147–189. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, L.; Naumann, A. Uber die grundlegenden Gerechnungen bei der Schwerkraftaufbereitung. Z. Ver. Dtsch. Ing. 1933, 77, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Umekage, T.; Yuu, S. Measurement of drag force acting on spherical particle in multi-particle system. Trans. JSME 1999, 65, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, E.H. Kinetic Theory of Gases; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1938; pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, F.H.; Welch, J.E. Numerical calculation of time-dependent viscous incompressible flow of fluid with free surface. Phys. Fluids 1965, 8, 2182–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycroft, C.H.; Wong, Y.L.; Bazant, M.Z. Fast spot-based multiscale simulations of granular drainage. Powder Technol. 2010, 200, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycroft, C.H.; Bazant, M.Z. Dynamics of random packing in granular flow. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 73, 051306:1–051306:7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sielamowicz, I.; Blonski, S.; Kowalewski, T.A. Optical technique DPIV in measurements of granular material flows, Part 1 of 3-plane hoppers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennec, T.L.; Maloy, K.J.; Flekkoy, E.G.; Messager, J.C.; Ammi, M. Silo hiccups: Dynamic effects of dilatancy in granular flow. Phys. Fluids 1998, 10, 3072–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veje, C.T.; Dimon, P. The dynamics of granular flow in an hourglass. Granul. Matter. 2001, 3, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muite, B.K.; Hunt, M.L.; Josph, G.G. The effects of a counter-current interstitial flow on a discharging hourglass. Phys. Fluids 2004, 16, 3415–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B.; Stewart, W.E.; Lightfoot, E.N. Transport Phenomena; John Wiley and Sons Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1960; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Calculation of Eaij in SPH

Appendix B: Non-linear Functions of A1, A2, A3, and A4 in Constitutive Equations (1)–(6)

| A1 = 9.4 × 1013a2 + 2.0 × 109a + 9.0 × 105, 0 ≤ a < 0.000045 |

| A1 = −8.0 × 1014a2 + 8.0 × 1010a − 8.0 × 105, 0.000,045 ≤ a < 0.00005 |

| A1 = −1.2 × 1017a3 + 6.7 × 1013a2 − 1.4 × 1010a + 1.7 × 106, 0.000,05 ≤ a < 0.0002 |

| A1 = 1.2 × 1012a2 − 2.1 × 109a + 1.1 × 106, 0.0002 ≤ a < 0.0004 |

| A1 = −3.6 × 1014a3 + 1.2 × 1012a2 − 1.5 × 109a + 9.0 × 105, 0.0004 ≤ a < 0.001 |

| A1 = −3.8 × 1012a3 + 4.1 × 1010a2 − 2.0 × 108a + 4.4 × 105, 0.001 ≤ a < 0.0035 |

| A1 = −1.4 × 1012a3 + 2.7 × 1010a2 − 1.6 × 108a + 4.1 × 105, 0.0035 ≤ a < 0.007 |

| A1 = −6.2 × 108a3 + 5.5 × 107a2 − 2.1 × 106a + 4.1 × 104, 0.007 ≤ a ≤ 0.035 |

| A2 = 9.4 × 1013a2 + 2.0 × 109a + 3.0 × 105, 0 ≤ a < 0.000045 |

| A2 = −8.0 × 1014a2 + 8.0 × 1010a − 1.4 × 106, 0.000,045 ≤ a < 0.000055 |

| A2 = 7.8 × 1016a3 − 6.2 × 1012a2 − 4.8 × 109a + 8.5 × 105, 0.000,055 ≤ a < 0.00016 |

| A2 = −7.0 × 1015a3 + 7.4 × 1012a2 − 2.6 × 109a + 5.0 × 105, 0.000,16 ≤ a < 0.00045 |

| A2 = −2.3 × 1014a3 + 6.2 × 1011a2 − 5.7 × 108a + 3.3 × 105, 0.000,45 ≤ a < 0.001 |

| A2 = 1.7 × 1013a3 − 9.5 × 1010a2 + 1.2 × 108a + 1.0 × 105, 0.001 ≤ a < 0.0025 |

| A2 = −2.7 × 1011a3 + 6.9 × 109a2 − 5.8 × 107a + 2.0 × 105, 0.0025 ≤ a < 0.007 |

| A2 = 3.1 × 108a2 − 8.5 × 106a + 7.6 × 104, 0.007 ≤ a < 0.012 |

| A2 = 1.5 × 106a2 − 5.7 × 105a + 2.6 × 104, 0.012 ≤ a ≤ 0.035 |

| A3 = 7.3 × 1012a2 + 7.3 × 107a + 3.0 × 105, 0 ≤ a < 0.000165 |

| A3 = −1.8 × 1014a2 + 6.2 × 1010a − 4.7 × 106, 0.000,165 ≤ a < 0.000175 |

| A3 = 1.5 × 1016a3 − 1.1 × 1013a2 + 5.7 × 108a + 6.5 × 105, 0.000,175 ≤ a < 0.0004 |

| A3 = −1.2 × 1014a3 + 5.1 × 1011a2 − 7.4 × 108a + 3.9 × 105, 0.0004 ≤ a < 0.0016 |

| A3 = −9.0 × 1011a3 + 1.1 × 1010a2 − 4.8 × 107a + 7.4 × 104, 0.0016 ≤ a < 0.004 |

| A3 = −2.3 × 1010a3 + 1.5 × 109a2 − 1.4 × 107a + 3.2 × 104, 0.004 ≤ a < 0.007 |

| A3 = 6.7 × 109a3 − 2.8 × 108a2 + 3.9 × 106a − 1.9 × 104, 0.007 ≤ a < 0.015 |

| A3 = −2.2 × 105a2 + 4.4 × 104a − 1.9 × 103, 0.015 ≤ a ≤ 0.035 |

| A4 = 4.6 × 1010a2 + 1.4 × 106a + 1.5 × 103, 0 ≤ a < 0.00011 |

| A4 = −3.0 × 1011a2 + 7.2 × 107a − 2.1 × 103, 0.00011 ≤ a < 0.000,13 |

| A4 = 3.1 × 1012a3 − 5.7 × 108a2 − 3.7 × 106a + 2.7 × 103, 0.000,13 ≤ a < 0.00055 |

| A4 = −3.9 × 1011a3 + 1.9 × 109a2 − 3.2 × 106a + 2.3 × 103, 0.000,55 ≤ a < 0.0019 |

| A4 = −2.7 × 109a3 + 4.6 × 107a2 − 2.8 × 105a + 7.3 × 102, 0.0019 ≤ a <0.006 |

| A4 = −7.4 × 107a3 + 3.1 × 106a2 − 4.6 × 104a + 3.0 × 102, 0.006 ≤ a < 0.015 |

| A4 = 6.9 × 104a2 − 5.0 × 103a + 1.1 × 102, 0.015 ≤ a ≤ 0.035 |

| where a = (Eaij Eaij)0.5 |

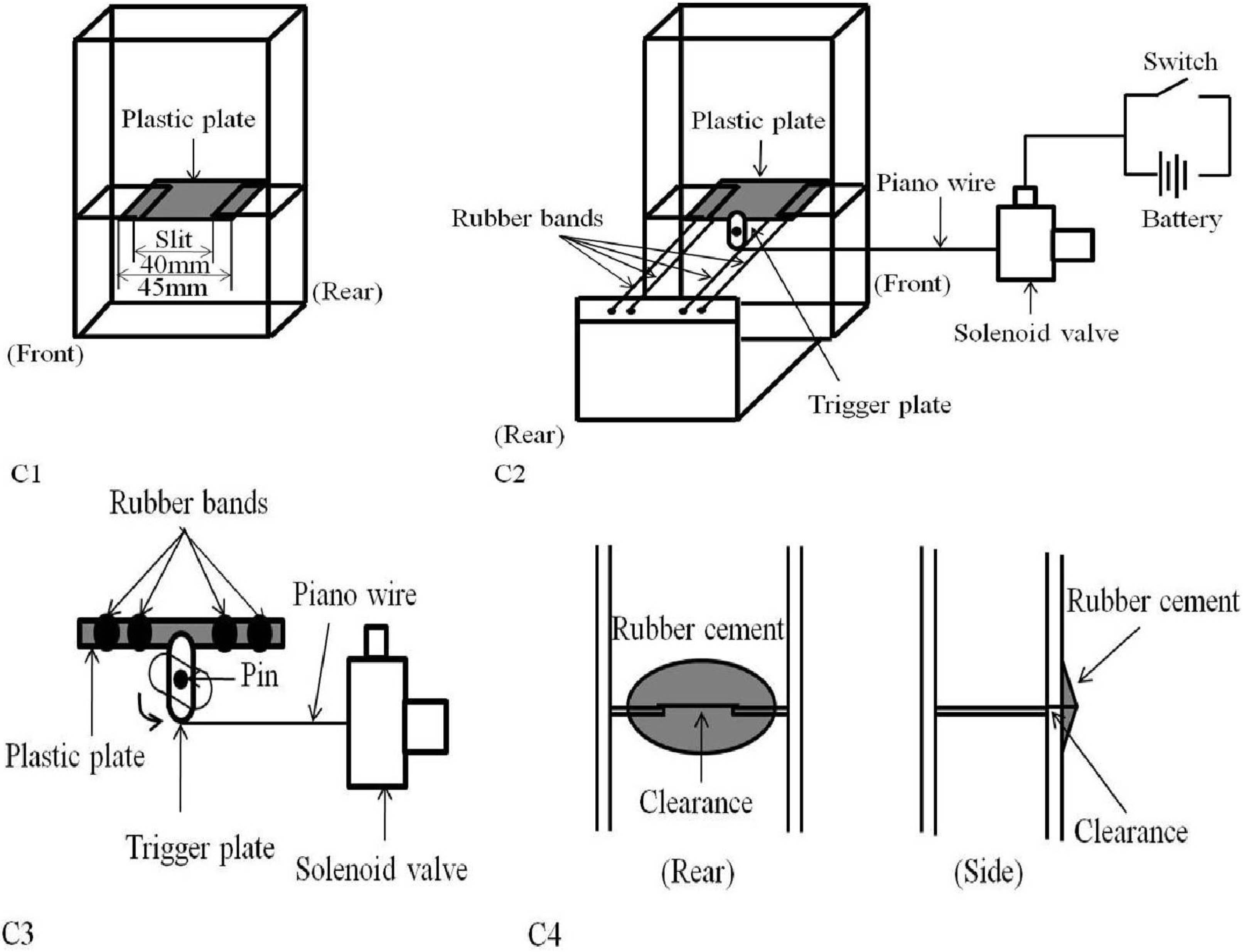

Appendix C:

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuu, S.; Umekage, T. Simulation of Granular Flows and Pile Formation in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin, and Experimental Verification. Materials 2011, 4, 1440-1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081440

Yuu S, Umekage T. Simulation of Granular Flows and Pile Formation in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin, and Experimental Verification. Materials. 2011; 4(8):1440-1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081440

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuu, Shinichi, and Toshihiko Umekage. 2011. "Simulation of Granular Flows and Pile Formation in a Flat-Bottomed Hopper and Bin, and Experimental Verification" Materials 4, no. 8: 1440-1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma4081440