The Interaction between FSC Certification and the Implementation of the EU Timber Regulation in Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Legality Verification and Forest Certification in Romania

2. Theoretical and Analytical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

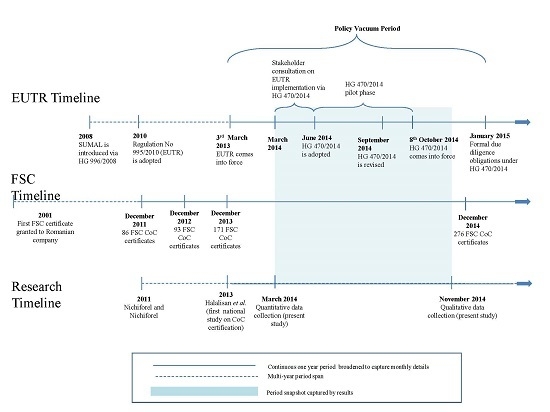

4.1. The EUTR Implementation Process

4.2. Can EUTR Requirements Be Covered by FSC Certification?

| EUTR: Risk Assessment Procedure and Risk Mitigation Procedures Criteria | FSC Certification Scheme | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Assessment Procedures | Assurance of compliance with applicable legislation, which may include certification or other third-party-verified schemes which cover compliance with applicable legislation. | Principle 1 includes legality criteria and national application of legality |

| Prevalence of illegal harvesting of specific trees pecies | Certification/verification is made by a body which is accredited to evaluate against a forest management/chain of custody standard. | |

| Prevalence of illegal harvesting or practices in the country of harvestand/or sub-national region where the timber was harvested, including consideration of the prevalence of armed conflict. | Certification/verification audits include review of documentation and system, and assessment in the forest/company. | |

| Complexity of the supply chain of timber and timber products. | The mixing of certified/verified and uncertified material in a product or product line is allowed, but the uncertified material must be covered by a verifiable system which is designed to ensure that it complies with legality requirements (FSC Controlled Wood). | |

| Risk Mitigation Procedures | Except where the risk identified is negligible, risk mitigation procedures may include requiring additional information or documents and/or requiring third party verification. | |

“Forestry certification does not have any effect on illegal logging…zero”; “A large company such as (…) has 500 suppliers. (…) is certified. Certification is useless, because those 500 suppliers do whatever they want in the forest.”(Forest Owner Association)

“For mega-processors… I don’t give any names, but for those mega-processors who used to cut 1,000,000 cubic meters… I think they were very important beneficiaries of the (previous) system (…) there will be an impact on these (mega-processors), because as half of this torrent of small firms will disappear, they (mega-processors) might have problems”; “I don’t know how it’s possible to verify 2,000,000 cubic meters, yeah? Honestly, whatever system you had in place…”(Furniture Company)

4.3. The Relationship between FSC and EUTR Implementation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASFOR | Forest industry association in Romania |

| CoC | Chain of Custody |

| CA | Competent Authority |

| DDS | Due Diligence System |

| EU | European Union |

| EUTR | EU Timber Regulation |

| FM | Forest Management |

| FSC | Forest Stewardship Council |

| MoEWF | Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests |

| PEFC | Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification |

| SFM | Sustainable Forest Management |

| TBGI | Transnational Business Governance Interactions |

| WWF | World Wildlife Fund |

References

- Bouriaud, L.; Niskanen, A. Illegal logging in the context of the sound use of wood. In Strategies for the Sound Use of Wood; Economic Commission for Europe, Timber Committee; Food and Agriculture Organization, European Forestry Commission: Poiana Brasov, Romania, 2003; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- WWF Danube Carpathian Programme (DCP). Illegal Logging in Romania. Available online: http://wwf.panda.org/?247014/Thousands-in-Romania-protest-illegal-logging (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Peter, L. Romania Acts to Save Forests from Logging Spree—BBC News. Available online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-32792314 (accessed on 29 July 2015).

- Nichiforel, L.; Bouriaud, L.; Dragoi, M.; Dorondel, S.; Mantescu, L.; Terpe, H. Romania. In Forest Land Ownership Change in Europe. COST Action FP1201 FACESMAP Country Reports, Joint Volume; Živojinović, I., Weiss, G., Lidestav, G., Feliciano, D., Hujala, T., Dobšinská, Z., Lawrence, A., Nybakk, E., Quiroga, S., Schraml, U., Eds.; EFICEEC-EFISEE Research Report; University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU): Vienna, Austria, 2015; pp. 471–495. [Google Scholar]

- Bouriaud, L. Causes of illegal logging in central and eastern Europe. Small Scale For. Econ. Manag. Policy 2005, 4, 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Nichiforel, R.; Nichiforel, L. Perception of relevant stakeholders on the potential of the implementation of the “Due Diligence” system in combating illegal logging in Romania. J. Horticult. For. Biotechnol. 2011, 15, 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Knorn, J.; Kuemmerle, T.B.; Radeloff, V.C.; Keeton, W.S.; Gancz, V.; Biriş, I.A.; Svoboda, M.; Griffiths, P.; Hagatis, A.; Hostert, P. Continued loss of temperate old-growth forests in the Romanian Carpathians despite an increasing protected area network. Environ.Conserv. 2013, 40, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatham House Illegal Logging Portal. Available online: http://www.illegal-logging.info/regions/romania (accessed on 29 July 2015).

- WWF. EU Must Tackle Illegal Logging in Own Borders, Says WWF. Available online: http://www.wwf.eu/?19303/EU-must-tackle-illegal-logging-in-own-borders-says-WWF (accessed on 29 July 2015).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 995/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 October 2010 Laying Down the Obligations of Operators Who Place Timber and Timber Products on the Market. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32010R0995 (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Halalisan, A.F.; Marinchescu, M.; Popa, B.; Abrudan, I.V. Chain of custody certification in Romania: Profile and perceptions of FSC certified companies. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSC Public Search. Available online: http://www.info.fsc.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2015).

- PEFC Facts & Figures. Available online: http://www.pefc.org/about-pefc/who-we-are/facts-a-figures (accessed on 9 November 2015).

- Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). In Market Info Pack; Forest Stewardship Council: Bonn, Germany, 2015.

- Giurca, A.; Jonsson, R.; Rinaldi, F.; Priyadi, H. Ambiguity in timber trade regarding efforts to combat illegal logging: Potential impacts on trade between south-east Asia and Europe. Forests 2013, 4, 730–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proforest. Main Report—Assessment of Certification and Legality Verification Schemes For European Timber Trade Federation (ETTF); Proforest: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Halalisan, A.F.; Marinchescu, M.; Abrudan, I.V. The evolution of forest certification: A short review. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. 2012, 5, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dieguez, L. The European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR) and Its Interactions with the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) Certification Scheme in the UK. Master Thesis, University of Freiburg, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 30 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen, J.; Toppinen, A.; Perttula, S. Impact of European Union timber regulation on forest certification strategies in the Finnish wood industry value chain. Forests 2015, 6, 2879–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkema, R.; Junginger, M.; van Dam, J.; Stegeman, G.; Durrant, D.; Faaij, A. Legal harvesting, sustainable sourcing and cascaded use of wood for bioenergy: Their coverage through existing certification frameworks for sustainable forest management. Forests 2014, 5, 2163–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trishkin, M.; Lopatin, E.; Karjalainen, T. Exploratory assessment of a company’s due diligence system against the EU timber regulation: A case study from Northwestern Russia. Forests 2015, 6, 1380–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Overdevest, C.; Zeitlin, J. Constructing a transnational timber legality assurance regime: Architecture, accomplishments, challenges. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 48, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Stone, M.W. Can legality verification rescue global forest governance? Analyzing the potential of public and private policy intersection to ameliorate forest challenges in Southeast Asia. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, T. Transnational governance and the re-centered state: Sustainability or legality? Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M. The (Self-) Regulation of Timber Legality—Thepractical Implementation of the EU Timber Regulation in Germany and Spain. Master thesis, University of Freiburg, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 19 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, R.; Giurca, A.; Masiero, M.; Pepke, E.; Pettenella, D.; Prestemon, J.; Winkel, G. Assessment of the EU Timber Regulation and FLEGT Action Plan; From Science to Policy 1; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nostra Silva. WWF Letter to the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change on measures necessary for the implementation of Regulation (EU) 995/2010. Available online: http://www.nostrasilva.ro/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2013-02-08-NOSTRA-SILVA-WWF-propuneri-EUTR-HG-996-SUMAL-4.pdf (acceseed on 18 December 2015).

- Eberlein, B.; Abbott, K.W.; Black, J.; Meidinger, E.; Wood, S. Transnational business governance interactions: Conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Clark, W.J.; Jones, D.L. Innovation policy vacuum: Navigating unmarked paths. Technol. Soc. 2011, 33, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.C.; Cooper, J.A.; McKenna, J.; Jackson, D.W.T. Shoreline management in a policy vacuum: A local authority perspective. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, A.M.; Ballinger, R.C. Implementing Integrated Coastal Zone Management in a national policy vacuum: Local case studies from Ireland. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halalisan, A.F. Regulation No 955/2010 and FSC forest certification. Rev. Silvicult. Cineg. 2014, 34, 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Climate Change andWWF Danube Carpathian Programme (DCP). Best practice guideline for the proper implementation of Regulation (EU) 995/1010; December 2014. Available online: http://apepaduri.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Ghid-DDS-pt-postare-15-ian-2015.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- WWF Government Barometer 2014. Available online: http://barometer.wwf.org.uk/what_we_do/government_barometer/ (accessed on 9 November 2015).

- FSC-Watch. The Joke That Is FSC’s “Controlled Wood Standard”: The Laundry Is Open for Business. Available online: http://www.fsc-watch.org/archives/2006/11/13/The_joke_that_is_FSC_s__Controlled_Wood_Standard___the_laundry_is_open_for_business (accessed on 29 July 2015).

- Giurca, A.; Jonsson, R. The opinions of some stakeholders on the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR): An analysis of secondary sources. iForest Biogeosci. For. 2015, 8, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavrilut, I.; Halalisan, A.-F.; Giurca, A.; Sotirov, M. The Interaction between FSC Certification and the Implementation of the EU Timber Regulation in Romania. Forests 2016, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7010003

Gavrilut I, Halalisan A-F, Giurca A, Sotirov M. The Interaction between FSC Certification and the Implementation of the EU Timber Regulation in Romania. Forests. 2016; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavrilut, Ines, Aureliu-Florin Halalisan, Alexandru Giurca, and Metodi Sotirov. 2016. "The Interaction between FSC Certification and the Implementation of the EU Timber Regulation in Romania" Forests 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7010003

APA StyleGavrilut, I., Halalisan, A. -F., Giurca, A., & Sotirov, M. (2016). The Interaction between FSC Certification and the Implementation of the EU Timber Regulation in Romania. Forests, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/f7010003