1. Introduction

Forests and carbon sequestration have become fundamental themes in climate change governance. Since the Bali Action Plan (2007), Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+) has gained significant influence on how forests are viewed and governed in developing countries [

1] and REDD+ has been considered as a game changer shifting forests into the center of global climate change politics [

2]. The REDD+ framework has provided a way for developed countries to offset carbon emissions and enabled forest-rich developing countries to receive payment for conservation. The Paris Climate Agreement signed in December 2015 has further cemented the role of REDD+ in the future of global climate governance. Significant progression has taken place in recent years in the REDD+ readiness process. Numerous countries are approaching final national REDD+ strategies and reference levels submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

REDD+ is based on a simple and appealing idea; however, turning the idea into action is much more complex [

3]. REDD+ was initially hailed as a smart and cost-effective way to mitigate climate change. As it is rolling out, ambiguities and controversies are increasingly surfacing to the stakeholders and actors at different levels. Though general guidelines on how to operationalize REDD+ have now been agreed upon by the UNFCCC, REDD+ is still heavily debated and remains unclear in practice regarding its conceptualization, required political and economic architecture, and its potential long-term impacts [

4].

REDD+ policy has been debated in national arenas among wide arrays of actors including national and international, state and non-state actors with varying levels of power to influence the policy [

5]. Many new actors have entered the arena and old actors have gradually changed their interest, beliefs, roles, and relationships leading to changing dynamics. It is important to understand how different actors with sometimes contradictory goals and different degrees of social, economic and political power are contributing to the debate, design and framing of REDD+ architecture [

6]. Considerable research has been done at the global level specially focusing on the technical implementation of REDD+ and in a global context [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Much less literature has analyzed the discourses and dynamics between actors involved in REDD+. As the analytical understanding of these national and local levels remains limited, scholars are starting to express concern about the large gap in the existing knowledge [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] not least because the success of REDD+ implementation is vitally linked to the local knowledge, support and stake. In this light, this research uses a multi-scale case study of forest governance to examine how actors emerged at national and local levels and how REDD+ discourses have evolved among them at the interface of global interests in carbon commodification vis-à-vis the local realities of community forestry.

Nepal represents an interesting case with its long history of multiple stakeholder involvement in forest management at different levels, strong local forest governance, and a range of actors and diverse perspectives that challenge, and review, fundamental and unresolved conflicts of REDD+ between global paradigms and local practices.

International communities have identified Nepal’s forests as an opportunity to tackle emissions reduction and sequestration through carbon trading in the global market while local communities are managing forests for their livelihood and cultural needs. Nepal is one of the early adopters of REDD+ and is in the process of developing policies, legal framework and organizational structure for its implementation [

20,

21,

22]. As the country is moving beyond its REDD+ readiness phase, this analysis aims to understand how REDD+ is perceived among different actors, whose voices and concerns are influential in the policy debate, and how REDD+ discourses have been shaped and received in the national policy arena.

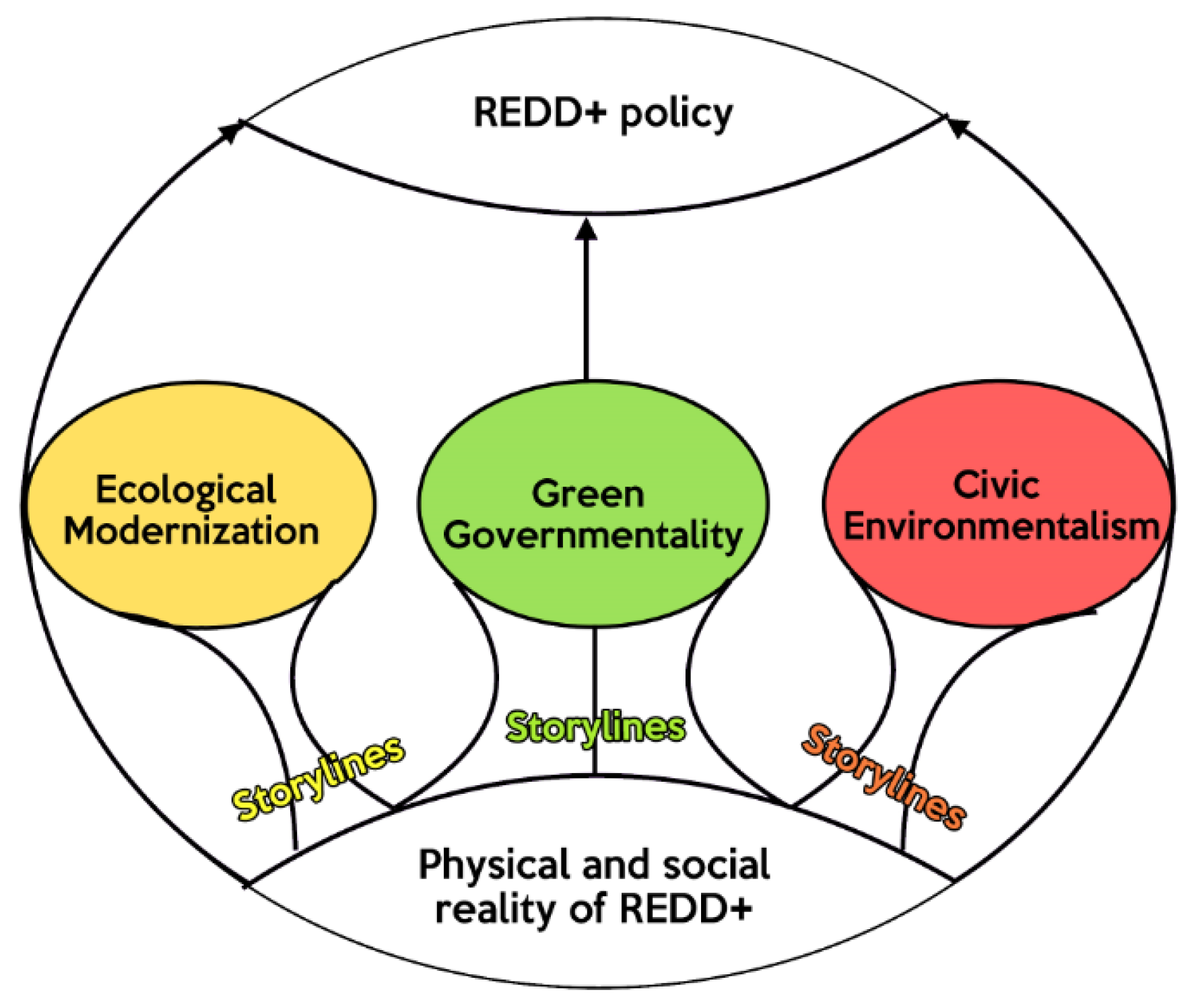

In discourse analysis, ideas, concepts and categories are not necessarily true or false, but they exist at the interface of politics, science, values and knowledge [

23]. Discourses are historically constructed within the existing social norms, various types of knowledge and power mechanisms in a society over long time frames [

24]. Actors involved in the discourses make sense of complex issues through the help of storylines that present core ideas, understandings and perceptions to their potential audiences. In responding to the knowledge gap with respect to national REDD+ policy discourses, the next section discusses the theoretical perspective to the political construction of REDD+ discourses and storylines among different actors.

Section 3 describes the study design and methods which includes interviews with policy actors and forest dependent community representatives, observation of policy events, and analysis of discursive materials.

Section 4 describes actors and their changing roles in Nepal’s forestry sector.

Section 5 explores policy actors’ views around the conceptualization and operationalization of REDD+ at national and sub-national levels. The discussion in

Section 6 then reflects how REDD+ storylines are connected with broader meta-discourses and how these discursive dynamics could influence the REDD+ policy process at the national level.

3. Methodological Approach

This paper builds on a combination of semi-structured interviews, focus group discussion, observations and document reviews from Nepal’s national policy level to local forest communities. The field work was conducted during a particularly important political time window (December 2013 to September 2014) when public consultations were underway to solicit comments on Emission Reduction-Program Idea Notes (ER-PIN), Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) and National REDD+ Strategy. A total of 82 face-to-face interviews were conducted across national and regional government, national and international non-profit organizations and research organizations, civil society representatives, and community individuals in three local forest communities in order to capture the full range of issues and concerns regarding REDD+ and its consultation process.

Two parallel sets of interview questions were used for the national and local levels to ensure they remained thematically comparable. The interviews with national policy actors focused on major forest policies changes in Nepal within past 30+ years, major actors in the policy process and their role; REDD+ policy process, major actors involved and their communication mechanism, interests and roles of different actors in the REDD+ process, compatibility of REDD+ with existing community forestry, and policy options to represent local priorities and needs in the global REDD+ program. Mirroring these, the interviews with local community members focused on understandings of REDD+, potential impacts of REDD+ on local socio-economic livelihoods, ecology, and governance.

The interview participants were purposively selected, comprising a dataset of 22 policy actors and 60 local community forest user group (CFUG) members from three community forests in the Mid-Hills, Inner Terai, and Terai. These three CFUGs were purposively selected to capture three different physiographic regions as well as different levels of exposure to REDD+ and carbon measurements. Bhakarjung CFUG (from Dhikurpokhari VDC, Kaski, Nepal) is located in the middle mountain region, with no prior exposure to REDD+. Rajapani CFUG (from Saljhandi VDC, Rupandehi, Nepal) is located in the Terai, with no prior REDD+ exposure but with basic carbon measurement experience through a Himalayan Community Carbon Project supported by Plan Vivo. Janapragait CFUG (from Shaktikhor and Siddhi VDC, Chitwan, Nepal) is located in the Inner Terai, with prior experience through a REDD+ pilot project funded by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD ).

Two different focus group discussions were conducted with special interest groups in each CFUG, including poor, women, and indigenous groups. Approximately seven to twelve participants were invited to each focus group discussion and the discussion was centered on forest resource access, local resource management and knowledge, as well as power relationships in local forest management and REDD+.

The interviews and focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed and analyzed using simple coding methods. During the preliminary analysis, the codes were regrouped in order to reflect the individual actors’ positions with respect to REDD+ elements, which yielded a matrix representing the extent to which each actor adheres to particular forms of storylines linking with three broad discourses as identified by Bäckstrand and Lövbrand [

37,

38]. The results from interview and focus group analysis were complemented by observation notes and secondary literature. The latter includes a collection of governmental report documents and brochures, as well as publications from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as complementing research data that underscores the research results and enhances understanding of REDD+ implementation in Nepal. Academic peer-reviewed and “grey” political literature on REDD+ were used as well. For observation data, the conducted field visits offered valuable deeper insights into the

de facto implementation of workshops, national dialogues, and project meetings by government actors, civil society, research institutions, and a series of consultation meetings organized for the preparation of Nepal’s National REDD+ Strategy.

Our empirical findings from primary and secondary resources are represented below in a narrative form, in order to outline central discourse features with respect to problem definition of deforestation in Nepal, the proposed strategy for reducing deforestation and the consequent construction of REDD+.

4. Actors and Their Changing Role in Nepal’s Forestry Sector

Nepal’s forest policy and its actors have been shaped through global political and environmental waves, as well as national events [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Specifically, stories of Himalayan degradation in the 1970s, the structural adjustments of the 1980s, and carbon forestry efforts after 2007 constituted major global waves that affected forest policies and (re)shaped the political landscape of Nepal’s forest governance. In addition, major political changes in the country and learning from experience have also been reflected in Nepal’s forest policy development and in defining actors’ roles in the deliberation process.

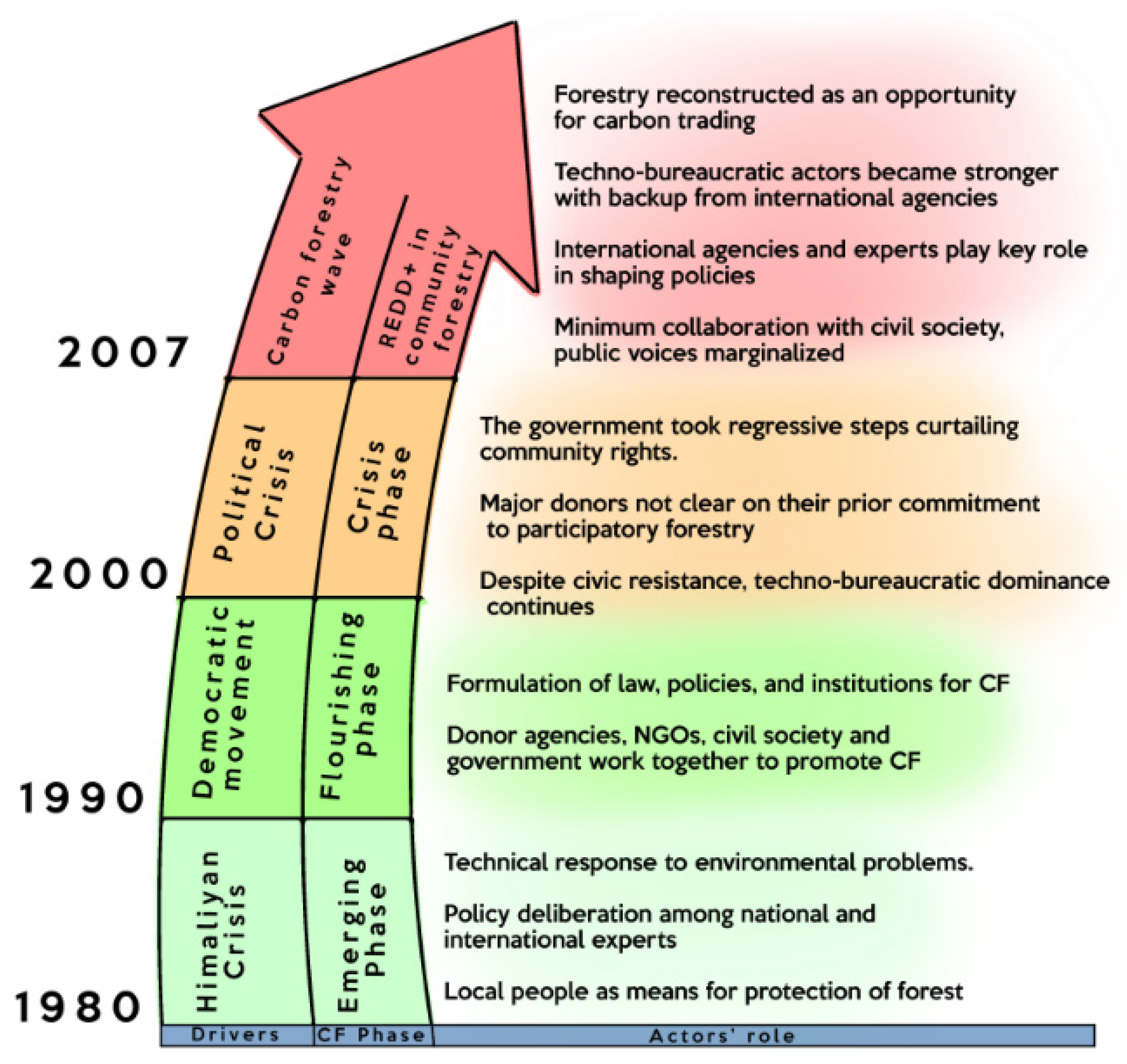

Figure 2 (see below) gives a broad overview about global and national drivers that affected Nepal’s forest policies and its actors throughout different phases of forest governance. The evolutionary process is roughly simplified here and depicted as a linear pathway, but in practice these processes were interconnected and overlapped in complex ways [

44].

Before the late 1970s, Nepal’s forest governance was mainly controlled by state-centric techno-bureaucratic power that excluded the people from forest management in the name of nationalization of privately controlled forestlands. Concerns over Himalayan degradation and subsequent failure of a technical response through large-scale plantation mobilized rethinking among techno-bureaucrats and donors, and opened the door for participatory forest reforms. In the 1980s, the global wave of structural adjustment policies was growing stronger and Nepal was affected as well. Donors pressured the government for a clearer commitment to decentralization and devolution of resource management in the 1989 Master Plan of the Forestry Sector. However, policy deliberations for the Master Plan took place only among national and international experts without consulting the local people. The Master Plan for the Forestry Sector became a milestone for Nepal’s formal policy development toward participatory forest governance. This can be categorized as the emerging phase of community forestry in Nepal.

Following the revolution of 1990, and the restoration of multi-party democracy in the country, civil society regained influence and demanded the devolution of forest rights to the local communities. Nepal’s government promulgated the progressive Forest Act of 1993 and the Forest Regulation of 1995 to pave the way for pluralistic approaches in forest governance, thus giving the local people a greater sense of ownership in local forests. Consequently, state forest lands were increasingly handed to local forest users for management and use. With the increased number of community forest user groups, a national network of forest users—the Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal (FECOFUN)—was established in 1995 to safeguard the users’ rights. Gradually, community forestry became very successful as it moved beyond the protection-oriented forestry regime of the past. Multi-lateral and bi-lateral agencies, NGOs, civil society, and government agencies worked together to promote community forestry in the hills. This represented the flourishing phase of community forestry in Nepal.

During the Maoist-led civil war, local forestry groups practiced

de facto self-governance in the absence of locally elected governments. The government was reluctant to speed up the forest handover to the local communities; instead, it imposed stricter techno-bureaucratic control upon the local forest users. The government banned the harvesting of green trees, proposed taxes on community forestry products and imposed a bureaucratic and inaccessible forest inventory system [

43,

47]. The Royal takeover of 2005 further increased techno-bureaucratic control over the local forests. Despite intense civic resistance, techno-bureaucratic dominance continued even after the abolition of Monarchy in 2006. Repeated threats to revise the Forest Act of 1993 in order to curtail local authority and expansion of new protected areas without adequate community consultation were some of the examples of techno-bureaucratic dominance. Even though donor communities had crucial roles in the earlier stages of community forestry, during the crisis major donors could not come up with clear positions to continue their prior commitments. Overall, the political turmoil and increased bureaucratic control undermining public deliberation pushed community forestry further into crisis.

After the Bali Convention of 2007, global climate change entered Nepal’s forest management agenda with strong commitments toward climate change mitigation. Forestry has since been reconstructed as an opportunity to sequester and trade carbon for climate change mitigation, establishing REDD+ as a new central tool of forest governance. As commented during our interview sessions by an environmental policy expert (see below), the agenda, policies and priorities of community forestry have been adapted to this global paradigm shift. The actors are attracted to the emerging agendas of forest carbon and climate change. During the early stages of REDD+, all Nepalese actors including the techno-bureaucratic actors, civil society and the community networks reported to have more or less equally regarded REDD+ as more beneficial than traditional forestry. Techno-bureaucratic dominance backing from the international donor agencies has gradually created an additional layer over the national policy deliberation, putting priorities on the carbon agenda over local rights and livelihoods. Bilateral and multilateral donors supported the piloting, knowledge generation and capacity building of various aspects of REDD+. However, our interview participants indicate that their collaborations with civil society networks have not grown but remained minimal, and community people have largely remained unaware of REDD+ and its emerging discourses.

The role of actors in Nepal’s forest policy arena is somehow linked with global context. Before the community forestry, the state was the only power. During the preparation of Master Plan, donors dominated the process. Local communities had important roles in the forest conservation during the initial days of community forestry. Now, their role is not as strong as it was in the 1990s. Our policies and priorities are gradually shifting towards globalization and capitalization. The issue of global climate change has already entered our forest policy debate.

An experienced environmental policy expert from civil society

As REDD+ is still rolling out, different actors are entering the policy arena and trying to shape their space and influence the policy process [

48]. The Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) has established a REDD Implementation Center in order to implement the REDD readiness activities in Nepal. The center is leading the country’s policy and program development; monitoring, reporting and verification; coordination among various stakeholders; disseminating information; capacity development; and ensuring benefit-sharing. At the higher level, the government has formulated an inter-ministerial policy steering agency called the REDD+ Apex Body, chaired by the Minister for Forests and Soil Conservation. This committee includes eleven different ministries within and beyond forestry, reflecting how the interests and concerns of REDD+ have grown beyond the Forest Ministry. At a civil society level, forestry as well as non-forestry groups and alliances are attracted in the REDD+ process. Community-based forest user groups networks, women networks,

Dalits, indigenous groups and their networks, private tree growers, research and development NGOs, and private consultant groups are other non-state actors observed in Nepal’s REDD+ policy landscape.

Developed based on the field observations and document review,

Table 1 outlines an overview of the major actor categories, their broader interests and influences as found in the analysis. Individual actors within these broad categories have stronger, weaker or different interest and powers in the REDD+ policy arena. For example, the MFSC is especially interested in the exercise of power and authority, retaining leadership and control over national REDD+ mechanisms [

20]. Non-forestry ministries, on the other hand, have lower stakes and less influence in REDD+ activities. Donor agencies and international NGOs have increased their interests in the REDD+ policy process. Continuing their longstanding involvement, they are deeply invested in maintaining public policy influence through funding, technical support, knowledge generating, up-scaling, and seeing their lessons incorporated in the national policy process. Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal (FECOFUN) and Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN) have secured their political space in the REDD+ policy debate in Nepal, but other civil society networks are struggling to be counted in the process. These civil society networks are interested in retaining the local people’s trust and confidence on REDD+ related issues and empowering their own constituencies.

Local communities are the only place-based actors in these REDD+ networks that are tied to local forest governance in practice. They are deeply invested in ensuring sustainability of their forest, reaping private and collective benefits from forest resource management and participating in the decision-making process to ensure maximum benefit from REDD+. The local elites are particularly interested in—and capable of—influencing local decision-making toward expanding alliances with non-place-based actors for their personal benefits [

15].

The private sector is another category of policy actors in REDD+ with a relatively weak presence. Private tree growers have been noticed in some policy debates on the regional and local level, but they were not as visible in the national policy arena. In contrast, private national and international consultancy companies have been observed to play key roles as knowledge brokers in these meetings, in strong alliance with international donor communities and the REDD+ Implementation Center.

Network interaction and power of the policy actors depend on their resource ties, information ties and shared interests [

8]. The government has great influence in potential funding sources, payment mechanisms and forest carbon markets, and it is the main authority that leads and moderates national policy deliberations for Nepal’s low carbon strategy. The government’s REDD+ Implementation Center represents the main and formal source of information for all the other actors. Donor agencies and international NGOs are also established as powerful actors with policy influence, recognized for their funding, technical support, and the generation of knowledge in the national policy process. World Bank, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Department of International Development (DfID), NORAD (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation), WWF (World Wildlife Fund), and Care are the primary international agencies observed as active and powerful in Nepal’s REDD+ policy process. Government and international agencies are more dominant in resource and information power, and they seem to share more common interests and platforms. Civil society organizations, especially from the community forestry network, indigenous people’s network, women's network and

Dalit networks, share common interests with respect to advocacy and empowerment. However, they mostly remain dependent on international agencies for funding, and on the government for detailed and timely information regarding REDD+ developments. As one of the critical respondents pointed out in the interviews (see below), the role of civil society networks in critical policy issues has been repeatedly weakened due to their increased dependency on external donors, tying them to those agendas instead of their own:

FECOFUN is a good example how the civil society organizations deviate from advocacy to project-sponsored agendas. Now, FECOFUN has become almost a sword without sharpness while it has been expected to challenge the critical power relation with donors and state. Donors want to engage the civil societies in their own agenda. In my twenty-year long observation, most of the actors in forestry sectors are engaging in the projects rather than sticking on their own agenda.

An experienced environmental policy expert from civil society

5. Storylines Around REDD+

Since the inception of REDD+, numerous actors have entered into the REDD+ policy arena with different interests and influences (see

Table 1). Examining underlying assumptions and rhetoric observed in the REDD+ debates, this section aims to identify key storylines among these diverse actors in Nepal’s REDD+ policy arena. These storylines provide symbolic references to develop common understandings which ultimately work as political devices to define the national REDD+ discourse and to influence its policy.

5.1. Win-Win

As in the global policy arena, some actors in Nepal are excited about REDD+, and they perceive REDD+ as a win-win solution for climate change mitigation, poverty reduction, and conservation. They consider REDD+ as means for the greening of development coupled with a strong belief that carbon trading, local forest use, and conservation can go hand-in-hand. According to the proponents of this storyline, REDD+ will bring additional benefits to the local people without limiting their livelihoods and cultural rights. Some respondents who believe this storyline focus on forest carbon whereas others see REDD+ as compatible with existing forest management practices. They anticipate some changes in access and benefits sharing at a local level, but they believe that with some harmonization, it can bring win-win outcomes. Most of the actors in this category are from conservation organizations, donor agencies, government and local elites. A sample of their comments is noted below.

REDD+ will bring additional benefits to the local people without limiting their livelihoods and cultural rights.

Respondent from a conservation organization

Carbon trade can bring more money than the sale of forest products. If we sell forest carbon, there could be certain limitations on forest products use, but we will have other alternatives. Due to the increasing impact of climate change, the scope of the forest will increase in the near future.

Local elite from REDD+ pilot area

However, according to a respondent from a policy research institution, at the beginning, all of the stakeholders were excited about REDD+ and perceived it as a win-win solution. Gradually, however, some of them have expressed declining interest in REDD+ while others have changed their perspective.

5.2. Cost Effective

As a result of Stern’s [

49] report, REDD+ has been proposed as a cost-effective solution to climate change mitigation at the global level. Proponents of REDD+ from developed countries advocate REDD+ against other technological innovations. This became the dominant storyline during the early stage of REDD+ discussion. However, the cost-effective storyline is not very strong among the Nepalese actors—only a few respondents believe in this storyline. The following comment is from a government actor:

REDD+ will definitely be cheaper than the technological solution. It is more viable especially in developing countries where there is the issue of deforestation and forest degradation. It can be done with relatively less investment.

Official from REDD+ Implementation Center, Government of Nepal

Some others also perceive REDD+ as a cost-effective measure, however, they believe it will only work if there is a global consensus, as noted by this international agency representative:

If we reach a global consensus, REDD+ will be a cost-effective solution for climate change.

Representative from an influential international agency

5.3. Carbon Commodification

Carbon commodification presents a way in which to govern forest carbon, namely through market-based approaches. Respondents agree that a global priority for REDD+ is carbon and it is bringing market rationality by giving value to standing trees. Respondents consider REDD+ as an instrument for a low carbon economy. During the interviews and interactions at the workshops, national level policy actors revealed that a global agreement for REDD+ will be done on carbon, and other issues such as socio-economic and environmental benefits will be a secondary issue. This storyline carries the notion of neoliberal conservation to achieve synergy between economic, ecological, and social aspects [

7]. A view from this group from a conservation organization is noted below.

The global priority of local forest management is to reduce emissions through deforestation and forest degradation and to enhance forest carbon stock. Based on the global priority, the national priority is shaped. Our national priority is to keep the forest intact by maintaining 40% forest cover and, of course, poverty reduction is our national priority. Mechanisms like REDD+ are important to reduce global emissions and to bring benefits at the national and local level.

Respondent from a conservation organization

Performance-based payment during the piloting phase also reflects that REDD+ is based on market logic and it brings value when there is a large amount of carbon in the forest. Strict conservation of the forest, with the goal of obtaining carbon money, indicates the commodification of carbon. However, the local reality reveals the controversy about carbon commodification, as noted by an indigenous community leader:

REDD+ Project tells us not to cut the trees. We should not touch the plants inside the boundary pillar of the plots. If we cut the trees, we will lose the carbon payment.

A Chepang community leader from REDD+ pilot area

After the first phase of REDD+ readiness work, the Nepalese government prepared an Emission Reduction Program Idea Note (ER-PIN) and presented it to the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility Carbon Fund for a further carbon finance operation. The payment in the project will be made based on the verified emission reductions resulting from curbed deforestation and enhanced forest carbon stock through better forest management [

50]. This project also promotes the carbon commodification storyline.

5.4. Techno-Managerial

Implementation of performance-based REDD+ projects hinges on the accurate and detailed accounting of emission reductions. This promotes the techno-managerial storyline that expert knowledge is essential for understanding and managing REDD+. Stocks and flows of carbon are therefore constructed as administrative domains responsive to certain forms of political rationality such as government regulation [

51]. The proponents of this storyline see forests as carbon pools and carbon sink, and consider forests as governable units for carbon. The ways in which carbon can be measured, quantified, demarcated, and statistically aggregated lead to a specific rationality, thereby placing a strong need on the role of institutions for good governance and effective laws to protect the environment and human well-being [

52].

During the REDD+ readiness phase, the projects led by WWF, ICIMOD and DFRS were focused on carbon measurement, monitoring, and verification [

53]. These projects support the techno-managerial storyline. The interaction with local communities from the ICIMOD-led pilot site reflects how the REDD+ is being interpreted at the grass-root level, as stated by the chairperson of a REDD+ piloted CFUG:

We can protect the forest but we need experts and highly educated people to measure the carbon in our forests.

Chair Person of REDD+ piloted CFUG

Nepal’s recently submitted ER-PIN has revealed a high level of commitment to adhere the FCPF methodological framework and IPCCC guidelines for measuring, verifying and reporting of forest carbon [

50]. This requires a high level of expert knowledge and the engagement of multi-level stakeholders. Observing these realities, stakeholders at the national level admit the technical and managerial complexity of REDD+ that might threaten local forest management towards recentralization in the name of technological requirements. This viewpoint is expressed below by a civil society leader:

REDD+ is a technical and managerial issue and local actors, especially from civil society, do not have the capacity to understand the issue. This puts REDD+ under the control of techno-bureaucrats.

Secretary, FECOFUN

5.5. Safeguards

This storyline recognizes the trade-off between economic growth, sustainable forest management, the social and cultural value of forests, and carbon sequestration. Although carbon benefit is seen as the main objective of REDD+, this storyline considers safeguards as a necessary condition to prevent risk. After the Warsaw Framework, safeguards have become a pre-requisite for REDD+ funding. Our data indicates that this storyline has become stronger among the REDD+ actors at all levels.

Based on the policy research and learning from pilot projects, the coordinator of a REDD+ pilot project led by ICIMOD—an organization working in the policy issues at the Hindu-Kush region—highlights the need for a strong safeguard mechanism:

Government should redefine the forest management objectives. Scientific forest management can be reconciled with REDD+. REDD+ has already defined five different activities but the social and environmental safeguard is very important and need to be considered seriously.

REDD+ policy researcher

The safeguards storyline recognizes that building robust safeguards helps to prevent negative impacts on non-carbon benefits while working for carbon benefits [

8,

54]. The respondents who believe in the safeguards storyline contend that REDD+ can be compatible with existing community forestry if strong safeguards are put in place, as noted below:

If we focus on climate change mitigation, we should only emphasize on carbon. However, if we add a safeguard to REDD+, it can be compatible with community forestry. Nepal's Readiness Plan Idea Note (R-PIN), REDD Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP) and Emission Reductions Program Idea Note (ER-PIN) indicate the importance of safeguards.

Representative from an influential international agency

The Nepalese government’s R-PP document, which was submitted to the FCPF/ World Bank in 2010, did not use the term “safeguards,” however, it fully supports the safeguards storyline. The document promises Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) to both avoid negative impacts and to ensure positive and additional REDD+ benefits in terms of securing livelihoods and the rights of local forest dependent communities, and for promoting the conservation of biodiversity.

However, some respondents are skeptical about this storyline as the meaning of “safeguards” depends upon who uses it and in what context. During the workshops and interviews, civil society representatives—especially those from indigenous communities—perceive safeguards as a means for the effective implementation of REDD+ through minimizing the social and environmental risks inherent in REDD+ activities. Nonetheless, they argue that without promoting opportunities for local communities to improve livelihoods, REDD+ is not likely to succeed.

5.6. Non-Carbon Benefit/Beyond Carbon

This storyline goes beyond the minimum set of safeguards and advocates for the promotion of co-benefits in REDD+ policies and practices [

54]. It emphasizes the social dimensions of REDD+ governance in terms of capacity building and in addressing the social drivers of deforestation and forest degradation [

1,

55,

56]. Unlike the win-win storyline that carries a neoliberal rationale of REDD+ by emphasizing the economic valuation of carbon, this storyline argues the need for incorporating non-carbon benefits in the REDD+ payment scheme to enhance the interest of the local community for the effective and sustainable implementation of REDD+. Civil society representatives especially advocate this storyline and want to see REDD+ as a vehicle for generating non-carbon benefits. During recent years, the priority of the Nepalese government has also shifted from a carbon focus to a co-benefit mechanism on REDD+ framing. The vision of Nepal’s national REDD+ strategy [

57] gives equal importance to carbon and non-carbon benefits and reads:

Optimize carbon and non-carbon benefits of forest ecosystems for the prosperity of the people of Nepal.

Vision of National REDD+ Strategy of Nepal, 2015

Civil society actors perceive REDD+ as one among many other climate change mitigation solutions, and they advocate co-benefit and additional opportunities for local people from REDD+. Local people cannot imagine any situation that does not provide their full use-rights to local forests for timber, fuelwood and fodder. They do not see any rationale to protect forests only for carbon and argue that financial compensation cannot fulfill the need for their forest products forever.

The Center for People and Forests (RECOFTC)—a regional organization working for the capacity building and rights of local people over forest resources—considers REDD+ benefits as an extra benefit for local people without comprising existing rights:

REDD+ benefits for the community are like the top of the cake. It should bring extra benefits for local communities. For this, the first and foremost point is the safeguards. Safeguards can motivate local people, but the safeguard mechanism should go beyond the preventive one to ensure extra benefits for local people. However, too radical views cannot work for REDD+.

Nepal Country Representative, RECOFTC

The actors who believe in this storyline consider that the success or failure of REDD+ will be determined not only by carbon emission reductions, but also by equity and access to non-carbon benefits for local and indigenous peoples [

58]. During the interview with the spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests, he admitted that Nepal cannot benefit by focusing only on carbon, therefore, the carbon benefit should be considered as an additional benefit for countries such as Nepal. He further argued for the need of international negotiation to secure non-carbon benefits from REDD+. Nepal has identified six non-carbon benefits associated with REDD+. However, it is yet to be clarified how they will be monitored and how the benefits will be shared [

50]. Therefore, respondents speculate that this may pose further challenges in implementation:

It is said that our country position is for non-carbon benefits. But, the question is “who is going to pay?” and “how can monitory value be given for non-carbon benefits?” International buyers might not have interest in paying for non-carbon benefits.

REDD+ policy expert from civil society

5.7. Governance Reform

The governance reform storyline recognizes REDD+ as a new layer in the existing forest management system and urges governance reform to redefine the role, responsibilities, and rights of stakeholders at multi-layers in the changing context [

59]. This storyline recognizes both the opportunities and challenges with REDD+. The global interest in local forest management under REDD+ is for curtailing deforestation and forest degradation, and sequestering carbon for climate change mitigation. However, this study shows that Nepal’s position for REDD+ is to focus on both carbon and non-carbon benefits. Nepal’s R-PP document emphasizes participatory and inclusive processes with multi-stakeholder collaboration, capacity building, respecting the rights of local communities and indigenous peoples, and mainstreaming gender and equity concerns at all levels [

53].

The supporters of this storyline urge simplification of the MRV (Measurement, Reporting, Verification), REL (Reference Emission Levels) and safeguard mechanisms. Otherwise, these supporters suspect that technical hegemony gives space to the globally powerful actors to manipulate these technical aspects for their own benefit, thus marginalizing the local actors. During the interview, a senior official from the Community Forestry Division, Department of Forests, expressed that:

If MRV, REL and safeguards are too technical, developing countries will not benefit from REDD+. Technology should be friendly for the local people and transferrable. Otherwise, complicated technology gives space to the developed countries for power plays.

A senior official from Department of Forests, Nepal

Despite the government’s commitment, the believers of the governance reform storyline see a huge challenge in receiving international attention for payment of the non-carbon benefits.

Community forestry, forest certification, biodiversity conservation or REDD+—whatever the program—all are top-down in nature and they follow a unidimensional “West is the best” model. However, these models will not favor the local forest-dependent people as the procedures are not good. In order to make the REDD+ successful at the ground level, the proponents should fully respect the concept of free, prior, and informed consent, and the policy should be perceived from a multi-dimensional perspective.

Official from Climate Change Program, NEFIN

Managing the forests as local commons for local livelihoods and the global commons for carbon at the same time adds complexity, and some policy actors who are in the research and knowledge development fields urge for policy action to resolve this issue.

Representatives from community forestry networks and the indigenous people’s alliance view the area for governance reform at the national level as defining carbon rights, respecting cultural rights, and maintaining transparency and downward accountability. They commend changing the one-dimensional “West is the best” model in conservation and development into a multidimensional approach that also includes local actors in decision-making:

We need to marry the community forestry and REDD+. There should not be a negative impact on livelihoods at the local level. If there are any negative consequences, they should be compensated for. Furthermore, there is always a risk of rampant deforestation in developing countries after getting access to the market. If we cannot improve the governance right away, I see the chances of deforestation, corruption, and mismanagement of resources after the intervention REDD+.

REDD+ policy researcher

Even though the priorities of actors are different according to the constituency they represent, most of the actors currently support the governance reform storyline. Some advocate the conservation premium in carbon payments while others focus on broader governance reform and implementation of community-driven and right-based approaches to REDD+ implementation. Others ask for simplification of carbon and non-carbon measurement technology and processes. Moreover, REDD+ is not a poverty-reduction program and international investors might not care about such issues. However, the actors see the room to plug other priorities with REDD+ resources, according to a local context. Researchers and advocates also indicate the possibility of non-market-based REDD+ financing.

5.8. Carbon Surrogacy

This storyline perceives REDD+ as a North–South divider [

60,

61] and a new form of colonization [

62]. It criticizes REDD+ as a cost-effective measure for the Global North in transferring the burden for carbon emission reduction to the Global South. According to this storyline’s believers, REDD+ does nothing at all to reduce the world's emissions. Rather, it shifts the burden of mitigating climate change onto the places and people not responsible for it, and least able to cope with it [

63]. However, there are not many in this critical mass who resist REDD+, and their voices are not strong in Nepal’s policy arena. However, some respondents from civil society, especially from the indigenous community, some of the leftist-leaning political followers, and some critical researchers raise the issue of community rights. They are skeptical about REDD+ and see the fear of Global North dominance in forest governance in the name of REDD+:

REDD+ seems beneficial for global and local elites. However, there is a fear that REDD+ might divide our society at the local level and divide developed and developing countries at the global level. In the name of financial benefits, there could be politics to ban forest-use rights and make us dependent.

Local political leader from a left leaning party

Thus, the supporters of this storyline perceive REDD+ to be a controversial issue. Like other offsetting mechanisms, REDD+ might give control to developed countries and the polluters. In the changing geopolitical context, the believers of this storyline consider the commodification of carbon as unavoidable due to global pressure, however, they emphasize being more cautious at the local level. For them, REDD+ is becoming a necessary evil:

Offsetting has been used as license for developed countries to continue emissions. So, if we only depend on REDD+, it will not be a sustainable solution. There should be shared but differentiated responsibilities to fix the climate change problem.

REDD+ policy expert from civil society

The strong believers of this storyline compare the market-based REDD+ mechanism to a surrogate mother and see no benefits at the local level from REDD+:

We are importing timber from Malaysia, while our timbers are decaying in the forest. In the name of carbon increment, we are not extracting any timber from our community forests. I feel like we are playing the role of surrogate mother to conserve carbon for developed countries and getting only a negligible amount from it.

Respondent from a REDD+ pilot CFUG

6. Discussion: Connecting the Storylines to Broader Climate Change Discourses

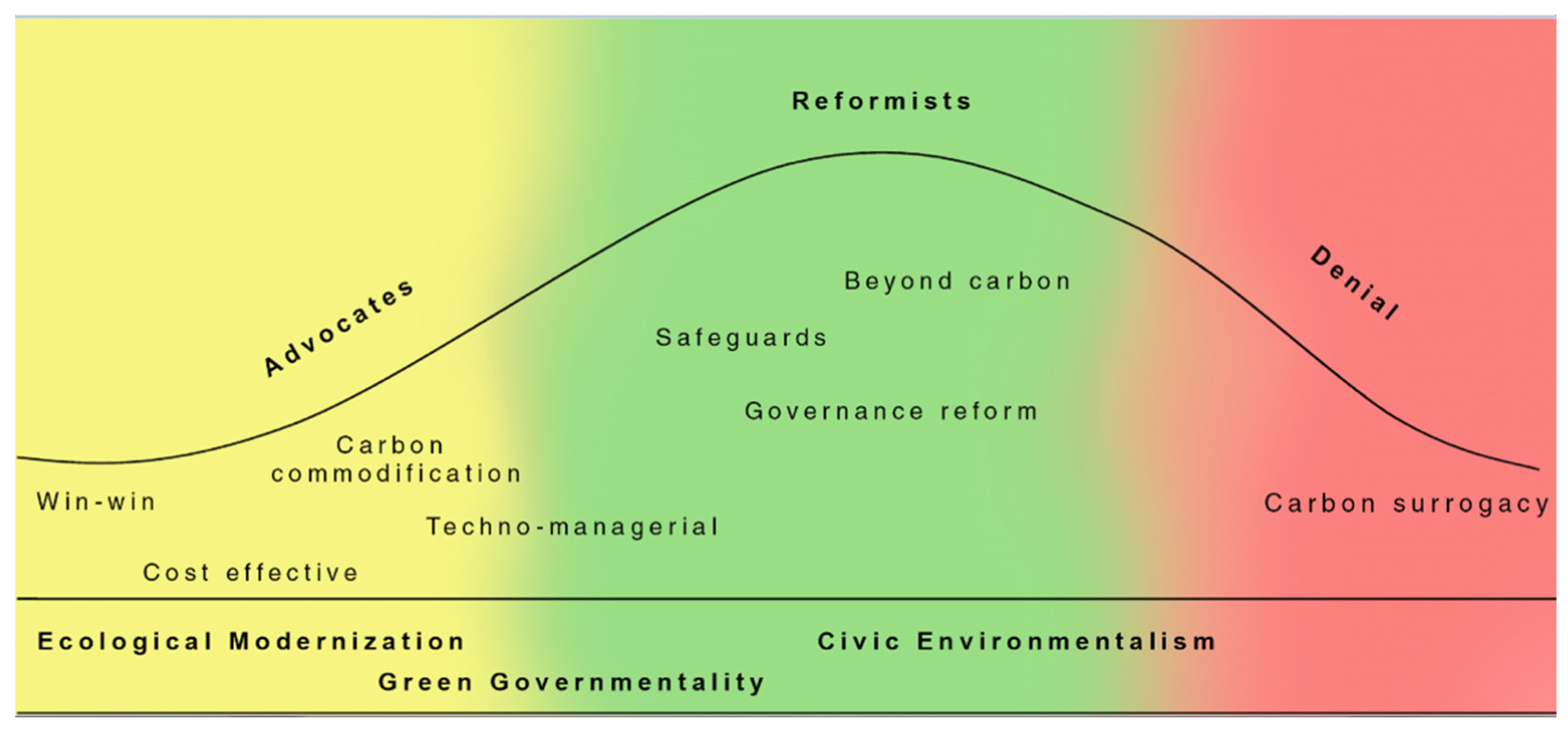

REDD+ is meant to achieve diverse purposes for various groups of people in different contexts. The storylines in the previous section demonstrate multiple ways of identifying the climate change problem and conceptualizing REDD+. Some of these storylines conflict with each other, whereas others are overlapping. In a broader spectrum, some storylines advocate the commodification and technocratization of forests carbon. Some others put forward more reformist agenda and urge for the incorporation of learning from participatory forest management, and to secure the local rights while conserving the forests for global climate change mitigation. On the other end, some storylines are very radical towards REDD+ and consider REDD+ as a false solution to climate change mitigation imposed by global north.

Below (

Figure 3), linking with the storylines described in the previous section, we adopt three meta-discourses that arguably underpin both policy practice and academic debate in environmental governance, particularly on the emergence of REDD+, as examined also by Bäckstrand and Lövbrand [

37,

38].

The first group of storylines frames REDD+ by the commodification of forests as a cost-effective approach to bringing a win-win solution. The commodification of forests goes further than timber to carbon, by putting a price on carbon and making it trade-able. In REDD+, forests are seen to yield carbon sink ecosystem services that can be quantified, verified, and compensated for [

64]. These storylines basically consider forests as instruments for low-cost climate change mitigation and for maximizing synergies. This group of storylines focuses on the monetization of carbon to combat climate change, to conserve the forests, and to secure local livelihoods. These storylines arose as the idea of REDD+ fundamentally emerged to keep tropical forests standing and carbon sequestered. The notion of “result-based payment” [

65] in REDD+ is that developed countries pay money to developing countries to lock the forest carbon by reducing deforestation and forest degradation. Measuring the carbon, and paying for the increased volume of carbon is basically a neoliberal and technocratic rationale that falls under “ecological modernization” meta-discourse [

38]. Storylines including “win-win”, “cost-effective,” “carbon commodification,” and “techno-managerial” favor the ecological modernization meta-discourse in REDD+ policy that confirms the tendency of REDD+ policy actors to favor measurable market solutions without questioning the socioeconomic tradeoffs. However, the protection of local rights and the participation of local people in policy deliberation remains marginal in this meta-discourse, although they are considered to be key for success [

20,

22,

66,

67].

The second group of storylines also focuses on the carbon constituted in the forests, but they emphasize the managerial and technical aspects of forest carbon measurement which falls broadly under the “green governmentality” meta-discourse [

38]. For them, carbon content, sequestration, and emissions are essential concepts for defining forests and forest management [

68]. This group of storylines renders nature and the environment measurable and calculable by setting quantitative standards, indicators, and criteria and by designing and implementing monitoring, reporting and verification systems [

64]. Carbon accounting has been portrayed as a key aspect of REDD+, which includes measuring and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions as well as setting the benchmarks against which performance is measured and payment for REDD+ is made [

69]. This group of storylines seeks precise and internationally reliable technical expertise for calculating the carbon content of forests and their value. It privileges scientific knowledge and expertise as an authoritative basis for governance and regulation, including markets [

25]. Field observation and interaction with the community people in the REDD+ piloting site reveals that the “techno-managerial” storyline has been strongly used at the grassroots level by the project proponents. Developing countries fear that calls to regulate forests under an international climate regime will increase the pressure for a

de facto internationalization of tropical forests, given their role in climate protection efforts. The success of REDD+ as a post-Kyoto regime depends upon the willingness of developed countries to accept differentiated responsibilities to provide adequate resources for REDD+, and to give compensation to developing countries for their acceptance of the obligation to reduce emissions through deforestation and forest degradation. Initially, REDD+ focused on the single function (either the storage of carbon or the emission of carbon) of forests and privileged the expertise of economists and remote sensing specialists [

54]. However, now the global debate has gradually deviated into safeguards and compensation mechanisms [

70]. Internationally, REDD+ emphasizes “do no harm” and contributing to improving the livelihoods of forest-dependent people. The program aims to prevent and mitigate harmful activities within program development and implementation [

71]. The safeguards storyline has been increasingly popular, but it still places its emphasis on carbon. Yet, there is a lack of agreement about the relative priority of carbon versus non-carbon values and the appropriate level of safeguard standards [

71]. “Governance reform” and “beyond carbon” storylines also support some elements of green governmentality.

The third group of storylines critiques both commodification and techno-bureaucratization of forests. This group disagrees with oversimplification of deforestation and calls for a sustained discussion on various issues such as tenure, the rights of indigenous peoples, and biodiversity instead of focusing solely on financial incentives for carbon [

7,

15]. These storylines focus on co-benefits, non-carbon benefits, human rights, and transformative change in governance through the management of forests which falls broadly under “civic environmentalism”. Supporters of this group of storylines consider that treating forests as global commons increases the pressure for

de facto internationalization of tropical forests, given their role in the global carbon cycle and importance in climate protection efforts [

72]. These storylines believe that simply paying for not cutting down trees is not sufficient, but that REDD+ should empower local stakeholders and offer livelihood activities in order to address the underlying causes of deforestation [

3,

20,

55,

73,

74,

75]. Therefore, the idea of non-carbon benefits has recently been internationally introduced which has also been reflected in Nepal’s policy debate. The recent National REDD+ Strategy of Nepal has emphasized the non-carbon benefit aspect [

57]. However, this idea is still clearly underdeveloped [

54]. This group of storylines also urges for governance reform. Otherwise, REDD+ becomes merely another means by which the Global North rules the Global South, in the name of carbon trading. “Non-carbon benefit/beyond carbon” and Governance reform” storylines support the reformist and soft category of civic environmentalism meta-discourse, which suggests increased multilateral, democratic and a bottom-up approach to make accountable institutions recognizing the multiple functions of forests, going beyond carbon. This group offers pragmatic and collaborative solutions for complex and multilevel climate change problems. However, at the extremist level, “carbon surrogacy” storyline supports the discourse that views REDD+ as a new form of colonization, or carbon-colonization. It also critiques REDD+ as carbon surrogacy by which developed countries are avoiding costly mitigation efforts at home while transferring the responsibility to developing countries at a low cost.

In a nutshell, this study broadly examined three meta-discourses in the larger realm of forest governance surrounding Nepal’s REDD+ policy discourses, each of which consists of several storylines. These meta-discourses reveal new as well as deeper connections with related discourses previously identified in environmental politics, and offers new methodological tools for their examination in policy practice from national actors to local forest communities.

The first meta-discourse supports a market-based approach to solve the climate change problem and treats forests as commodities. It conceptualizes carbon as a resource that can be traded. The second meta-discourse believes that science plays a central role in defining climate change problems. This discourse renders nature as measurable and calculable by setting quantitative indicators [

76] and it privileges scientific knowledge and expertise as the authoritative basis for governance, including the market [

25]. Both of these are top-down discourses in nature, and both confirm that REDD+ operates in the carbonization and the technocratization of forest governance [

77,

78]. In contrast, the third discourse is skeptical of market-based mechanisms as a primary design for the REDD+ program [

7]. This discourse adopts a bottom-up approach and believes in participation and stake-holding. This meta-discourse mostly urges for forestry governance reform and calls for a sustained discussion on various issues of social justice, including tenure and the rights of indigenous peoples, rather than solely focusing on financial incentives. However, the radical form of civic environmentalism takes a more critical style storyline rather than offering pragmatic solutions.

The political landscape that surrounds REDD+ in Nepal shows that there is a diversity of actors in the REDD+ policy arena (see

Table 1), and it supports different storylines based on the actors’ social constructs. As the policy process emerges, actors change their position, and one actor may carry more than one storyline in order to understand the problem and perceive the solution from their own institutional and/or personal reality. At the beginning, the REDD+ storylines were focused on the carbonization and technocratization of forests, and they were mostly led by international agencies including the World Bank, USAID, WWF and the Nepalese government. These actors advocated for performance-based REDD+ payment. However, unlike in other developing countries, private carbon market developers have not yet been seen in Nepal. In the early stages, civil society and indigenous groups were also optimistic about REDD+, seeing it as an opportunity for economic growth while offering a cost-effective and efficient solution to deforestation. However, once the discussion on the pros and cons of performance-based and market-led REDD+ governance took place at different levels, the stakeholders gradually changed their position from REDD+ advocacy to a more reformist line.

Globally, safeguards entered into the REDD+ policy debate in 2010, which influenced all of the actors at the national and local levels. Now, strong advocates of REDD+ shifted their storylines towards safeguards, realizing the fact that REDD+ should “do no harm” and should prevent risk to local people. However, the observation of the FCPF-supported program shows that the program is more focused on a risk-based approach and less firm in ensuring the rights of local and indigenous people. It does not go beyond preventive and mitigative safeguard measures. In contrast, general statements of the Nepalese government suggest that the national official focus does intend to go beyond carbon. Nepal’s R-PP reflects the beyond carbon/co-benefits storyline in the framing of REDD+. Nepal’s recent REDD+ strategy focuses on non-carbon benefits which support governance reform for REDD+ implementation. The programs led by conservation NGOs such as the WWF and Winrock emphasize scientific and technocratic storylines. However, national NGOs, civil society organizations, and international NGOs such as RECOFTC, who work on capacity building, emphasize that REDD+ policy and measures should respect international laws and conventions on human rights, and that social and environmental safeguards should be implemented. ICIMOD opines that REDD+ should not be an alternative to community forestry, but that both can go hand-in-hand to ensure community rights. However, it indicates the potentiality of non-market-based financing mechanisms as an alternative to the proposed market-based REDD+ approach. Actors from community forestry and indigenous peoples’ networks are more concerned about local and indigenous peoples’ rights, tenure security, and respect for their free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) when policies, programs, and projects are developed. Their storylines reflect that international agencies and governments are not serious about capacity building and deliberative policy process [

20]. They also reveal their suspicions about the proper implementation of international commitment at the local level. However, REDD+ denial groups at the institutional level are not observed in Nepal, despite some critical individuals from indigenous communities and some on the far political left, who portrayed REDD+ as a divider between developed and developing countries by carbon surrogacy.

7. Conclusions

This article first analyzed how the actors and their relationships have been changed in Nepal’s forestry governance due to the global paradigm shifts. Then, it uncovered different perspectives, understandings and views on REDD+ and forest governance. The study shows that Nepal government follows pluralistic policy approach and new actors are emerging in the policy field. Government, community groups, civil society organizations, international development agencies and private sectors are major categories of actors in Nepal’s forest and climate change policy landscape. Each and every actor has their own interests and power in REDD+ policy process. This research indicated that although there is vast array of actors interested in REDD+ policy process, it is mainly dominated by small group of experts, and limited number of NGO and civil society representatives, and most of the community people are not aware on it.

REDD+ discourses in Nepal evolve as they do in other parts of the world, and they are diverse in nature. One category of actors carries more than one storyline, and they do not necessarily stick to the same position over time. Some storylines complement, others contradict each other. These storylines broadly support three different global meta-discourses. The first group of storylines supports commodification of forest carbon as cost-effective and win-win solutions of global climate change; the second group still supports the commodification of forest carbon but focuses on technical and managerial aspects of carbon at multiple scales. The third group opposes an oversimplification of REDD+ in the name of carbon and urges for governance reform focusing on tenure, rights of local people, and multiple functions of the forest at multiple levels.

Actors employ different storylines and support respective discourses according to their social constructs. International donor agencies are more leaning toward advocating for REDD+, while the state government prefers its continued technical and managerial dominance with a moderate governance reform. In contrast, civil society actors and communities favor governance reform toward social and environmental security over the market and technological dominance. Smaller calls for complete rejection of REDD+ were also recorded during the study, although not strong at the institutional level.

This research offers a qualitative empirical analysis of the connection between power relations and the evolution of discourses on REDD+, and illustrates how some storylines can change, despite unfavorable power relationships. As REDD+ developed, its focus has changed from entirely market-oriented climate change mitigation to livelihoods and environmental concerns, including through the adoption of safeguard mechanisms by the UNFCCC.

The analysis of this case indicates that there is a broad variety of problem definitions surrounding climate change and possible policy solutions, thus emphasizing the need to honor the complexity of the issue with a sense of openness for dialogue at all levels. Bringing local narratives together with national and global narratives helps to broaden the knowledge base and consider policy solutions beyond economy-focused narratives. Our conclusions from this research urge for a stronger collaborative approach in REDD+ to enable multiple benefits of healthy forests, strong communities and effective climate change mitigation. These findings may offer similar relevance for other developing countries with significant community forestry and a strong commitment to REDD+.