Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Fungal Inoculum

2.3. Re-Isolation and Confirmation of H. fraxineus and Phytophthora spp.

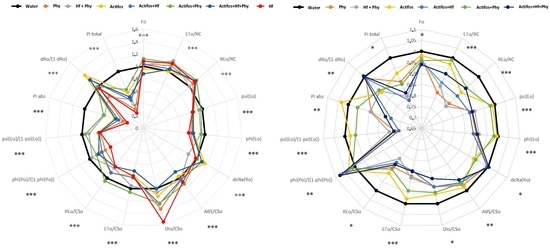

2.4. Chlorophyll-a Fluorescence Measurements

2.5. Analyses of Chemical Composition of Seedlings

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dobrowolska, D.; Hein, S.; Oosterbaan, A.; Wagner, S.; Clark, J.; Skovsgaard, J.P. A review of European ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.): Implications for silviculture. Forestry 2011, 84, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, G.; Cahalan, C. A review of site factors affecting the early growth of ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.). For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 188, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, B.; Tiefenbacher, H.; Litschauer, R.; Kirisits, T. Ash dieback in Austria—History, current situation and outlook. In Dieback of European Ash (Fraxinus spp.): Consequences and Guidelines for Sustainable Management; Vasaitis, R., Enderle, R., Eds.; SLU Service/Repro: Uppsala, Sweden, 2017; pp. 33–53, ISBN (print version) 978-91-576-8696-1; ISBN (electronic version) 978-91-576-8697-8. [Google Scholar]

- Przybył, K. Fungi associated with necrotic apical parts of Fraxinus excelsior shoots. For. Pathol. 2002, 32, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.M.; Blank, R.; Hartmann, G. Abiotic and biotic factors and their interactions as causes of oak decline in Central Europe. For. Pathol. 2002, 32, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharnweber, T.; Manthey, M.; Criegee, C.; Bauwe, A.; Schröder, C.; Wilmking, M. Drought matters—Declining precipitation influences growth of Fagus sylvatica L. and Quercus robur L. in north-eastern Germany. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaci, J.; Rozenbergar, D.; Anic, I.; Mikac, S.; Saniga, M.; Kucbel, S.; Visnjic, C.; Ballian, D. Structural dynamics and synchronous silver fir decline in mixed old-growth mountain forests in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Forestry 2011, 84, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oszako, T.; Delatour, C. Recent Advances on Oak Health in Europe; Forest Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2000; p. 281. ISBN 83-87647-20-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pacia, A.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Tkaczyk, M.; Sikora, K.; Tereba, A.; Borys, M.; Milenković, I.; Pszczółkowska, A.; Okorski, A.; Oszako, T. Common Ash Stand Affected by Ash Dieback in the Wolica Nature Reserve in Poland. Baltic For. 2017, 23, 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, T. Chalara fraxinea sp. nov. associated with dieback of ash (Fraxinus excelsior) in Poland. For. Pathol. 2006, 36, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, H.-O.; Queloz, V.; Hosoya, T. Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, the correct scientific name for the fungus causing ash dieback in Europe. IMA Fungus 2014, 5, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, T.; Holdenrieder, O. The teleomorph of Chalara fraxinea, the causal agent of ash dieback. For. Pathol. 2009, 39, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-J.; Hosoya, T.; Baral, H.-O.; Hosaka, K.; Kakishima, M. Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus, the correct name for Lambertella albida reported from Japan. Mycotaxon 2012, 122, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, V.; Borja, I.; Hietala, A.M.; Kirisits, T.; Solheim, H. Ash dieback: Pathogen spread and diurnal patterns of ascospore dispersal, with special emphasis on Norway. Bull. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 2011, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, L.V.; Nielsen, L.R.; Collinge, D.B.; Thomsen, I.M.; Hansen, J.K.; Kjær, E.D. The ash dieback crisis: Genetic variation in resistance can prove a long-term solution. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderle, R.; Metzler, B.; Riemer, U.; Kändler, G. Ash dieback on sample points of the National forest inventory in south-western Germany. Forests 2018, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, V.; Nagy, N.E.; Hietala, A.M.; Børja, I.; Solheim, H. Progression of Ash Dieback in Norway Related to Tree Age, Disease History and Regional Aspects. Baltic For. 2017, 23, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais, B.; Husson, C.; Caël, O.; Collet, C.; Dowkiw, A.; Saintonge, F.-X.; Delahaze, L.; Chandelier, A. Estimation of Ash Mortality Induced by Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in France and Belgium. Baltic For. 2017, 23, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks, J.J.; Buggs, R.J.A.; Lee, S.J. A first assessment of Fraxinus excelsior (common ash) susceptibility to Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (ash dieback) throughout the British Isles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enderle, R.; Nakou, A.; Thomas, K.; Metzler, B. Susceptibility of autochthonous German Fraxinus excelsior clones to Hymenscyphus pseudoalbidus is genetically determined. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollars, E.S.A.; Harper, A.L.; Kelly, L.J.; Sambles, C.M.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, R.H.; Swarbreck, D.; Kaithakottil, G.; Cooper, E.D.; Uauy, C.; Havlickova, L.; et al. Genome sequence and genetic diversity of European ash trees. Nature 2016, 541, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sambles, C.M.; Salmon, D.L.; Florance, H.; Howard, T.P.; Smirnoff, N.; Nielsen, L.R.; McKinney, L.V.; Kjær, E.D.; Buggs, R.J.A.; Studholme, D.J.; Grant, M. Ash leaf metabolomes reveal differences between trees tolerant and susceptible to ash dieback disease. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marciulyniene, D.; Davydenko, K.; Stenlid, J.; Cleary, M. Can pruning help maintain vitality of ash trees affected by ash dieback in urban landscapes? Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.L.; McKinney, L.V.; Nielsen, L.R.; Havlickova, L.; Li, Y.; Trick, M.; Fraser, F.; Wang, L.; Fellgett, A.; Sollars, E.S.A.; et al. Molecular markers for tolerance of European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) to dieback disease identified using Associative Transcriptomics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, D.; Grant, B. The complex action of phosphonates as antifungal agents. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1991, 66, 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrath, U.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Mauch-Mani, B. Priming in plant-pathogen interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalio, R.J.D.; Fleischmann, F.; Humez, M.; Osswald, W. Phosphite Protects Fagus sylvatica Seedlings towards Phytophthora plurivora via Local Toxicity, Priming and Facilitation of Pathogen Recognition. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, G.E.S.; Barrett, S.; Shearer, B.L. The future of phosphite as a fungicide to control the soilborne plant pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi in natural ecosystems. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2001, 30, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, H.T.B.; Yamakawa, T. Phosphite (phosphorous acid): Fungicide, fertilizer or bio-stimulator? Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2009, 55, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tkaczyk, M.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Oszako, T. Phosphite fertilizers as a plant growth stimulators in forest nurseries (in Polish with English summary). Sylwan 2014, 158, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I. Biostimulant activity of phosphite in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, M.; Pacia, A.; Siebyła, M.; Oszako, T. Phosphite fertilisers as inhibitors of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (anamorph Chalara fraxinea) growth in tests in vitro. Fol. For. Pol. Ser. A For. 2017, 59, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosz, T.; Kubiak, K.A.; Jacek, S.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Tomasz, O. The use of phosphates in forestry. For. Res. Pap. 2016, 77, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swoczyna, T.; Kalaji, H.M.; Pietkiewicz, S.; Borowski, J.; Zaraś-Januszkiewicz, E. Photosynthetic apparatus efficiency of eight tree taxa as an indicator of their tolerance to urban environments. Dendrobiology 2010, 63, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten, L.; Verheyen, K.; Wirth, C.; Bruelheide, H.; Bussotti, F.; Finér, L.; Jaroszewicz, B.; Selvi, F.; Valladares, F.; Allan, E.; et al. A novel comparative research platform designed to determine the functional significance of tree species diversity in European forests. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 15, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Goltsev, V.N.; Żuk-Gołaszewska, K.; Zivcak, M.; Brestic, M. Chlorophyll Fluorescence: Understanding Crop Performance—Basics and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; p. 222. ISBN 978-14-9876-449-0. [Google Scholar]

- Himejima, M.; Hobson, K.R.; Otsuka, T.; Wood, D.L.; Kubo, I. Antimicrobial terpenes from oleoresin of ponderosa pine tree Pinus ponderosa: A defense mechanism against microbial invasion. J. Chem. Ecol. 1992, 18, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepzig, K.D.; Kruger, E.L.; Smalley, E.B.; Raffa, K.F. Effects of biotic and abiotic stress on induced accumulation of terpenes and phenolics in red pines inoculated with bark beetle-vectored fungus. J. Chem. Ecol. 1995, 21, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witzell, J.; Martin, J.A. Phenolic metabolites in the resistance of northern forest trees to pathogens—Past experiences and future prospects. Can. J. For. Res. 2008, 38, 2711–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, B.M.; Manion, P.D. Antifungal compounds in aspen: Effect of water stress. Can. J. Bot. 1994, 72, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Simón, B.; Esteruelas, E.; Muňoz, A.M.; Cadahia, E.; Sanz, M. Volatile Compounds in Acacia, Chestnut, Cherry, Ash, and Oak Woods, with a View to Their Use in Cooperage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3217–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caligiani, A.; Tonelli, L.; Palla, G.; Marseglia, A.; Rossi, D.; Bruni, R. Looking beyond sugars: Phytochemical profiling and standardization of manna exudates from Sicilian Fraxinus excelsior L. Fitoterapia 2013, 90, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Schansker, G.; Ladle, R.J.; Goltsev, V.; Bosa, K.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Brestic, M.; Bussotti, F.; Calatayud, A.; Dąbrowski, P.; et al. Frequently asked questions about in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence: Practical issues. Photosynth. Res. 2014, 122, 121–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angay, O.; Fralischmann, F.; Recht, S.; Herrmann, S.; Matyssek, R.; Oβwald, W.; Buscot, F.; Grams, T.E. Sweets for the foe-effects of nonstructural carbohydrates on the susceptibility of Quercus robur against Phytophthora quercina. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenkhan, R.; Adamson, K.; Hanso, M. The earliest samples of Hymenoscyphus albidus vs. H. fraxineus in Estonian mycological herbaria. Mycol. Prog. 2016, 15, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Blaschke, H.; Neumann, P. Isolation, identification and pathogenicity of Phytophthora species from declining oak stands. Eur. J. For. Pathol. 1996, 26, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Račkovà, L.; Paganovà, V.; Swoczyna, T.; Rusinowski, S.; Sitko, K. Can chlorophyll-a fluorescence parametres be used as bio-indicators to distinguish between drought and salinity stress in Tilia cordata Mill? Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 152, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocki, M.; Zapora, E.; Rój, E.; Bakier, S. Recovering biologically active compounds from logging residue of birch (Betula spp.) with supercritical carbon dioxide. Przem. Chem. 2018, 97, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Laska, G.; Kiercul, S.; Stocki, M.; Bajguz, A.; Pasco, D. Cancer-chemopreventive activity of secondary metabolites isolated from Xanthoparmelia conspersa lichen. Planta Med. 2015, 81, PM_59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, G.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Stocki, M.; Sharma, V.; Zjawiony, J.; Jacob, M. Secondary metabolites from Pulsatilla patens and Pulsatilla vulgaris and their biological activity. Planta Med. 2015, 81, PM_122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V. Identification of Biologically and Environmentally Significant Organic Compounds Mass Spectra and Retention Indices Library of Trimethylsilyl Derivatives; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; p. 429. ISBN 9788301182571. [Google Scholar]

- Pliura, A.; Lygis, V.; Suchockas, Y.; Bartevicius, E. Performance of twenty four European Fraxinus excelsior popualtion in three Lithauanian progeny trials with a species emphasis on resistance to Chalara fraxinea. Baltic For. 2011, 17, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, M.R.; Arhipova, N.; Gaitnieks, T.; Stenlid, J.; Vasaitis, R. Natural infection of Fraxinus excelsior seeds by Chalara fraxinea. For. Pathol. 2013, 43, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pušpure, I.; Matisons, R.; Laviniņš, M.; Gaitnieks, T.; Jansons, J. Natural regeneration of common ash in young stands in Latvia. Baltic For. 2017, 23, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Tulik, M.; Zakrzewski, J.; Adamczyk, J.; Tereba, A.; Yaman, B.; Nowakowska, J.A. Anatomical and genetic aspects of ash dieback: A look at the wood structure. iForest 2017, 10, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, C.; Caël, O.; Grandjean, J.P.; Nageleisen, L.; Marҫais, B. Occurrence of Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus on infected ash logs. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, H.D.; Bartha, B.; Straβer, L.; Lemme, H. Development of Ash Dieback in South-Eastern Germany and the Increasing Occurrence of Secondary Pathogens. Forests 2016, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giongo, S.; Oliveira Longa, C.M.; Dal Maso, E.; Montecchio, L.; Maresi, G. Evaluating the impact of Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in Trentino (Alps, Northern Italy): First investigations. iForest 2017, 10, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakys, R.; Vasaitis, R.; Skovsgaard, J.P. Patterns and severity of crown dieback in young even-aged stands of european ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) in relation to stand density, bud flushing phenotype, and season. Plant Protect. Sci. 2013, 49, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirisits, T.; Cech, T.L. Beobachtungen zum sexuellen Stadium des Eschentriebsterben-Erregers Chalara fraxinea in Österreich [Observations on the sexual stage of the ash dieback pathogen Chalara fraxinea in Austria]. Forstschutz Aktuell 2009, 48, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield, M.J.; Seifert, K.A.; Webber, J. (Eds.) Ceratocystis and Ophiostoma: Taxonomy, Ecology, and Pathogenicity; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1993; p. 293, ISBN 10: 0890541566; ISBN 13: 9780890541562. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette, G.B.; Rioux, D.; Simard, M.; Cherif, M. Ultrastuctural and cytochemical studies of host and pathogens in some fungal wilt diseases: Retro- and introspection towards a better understanding of DED. For. Syst. 2004, 13, 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, J.; Dvořák, M. Sap flow-based quantitative indication of progression of Dutch elm disease after inoculation with Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Trees-Struct. Funct. 2014, 28, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakys, R.; Vasaitis, R.; Barklund, P.; Ihrmark, K.; Stenlid, J. Investigations concerning the role of Chalara fraxinea in declining Fraxinus excelsior. Plant Pathol. 2009, 58, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smillie, R.; Grant, B.R.; Guest, D. The mode of action of phosphite: Evidence for both direct and indirect modes of action on three Phytophthora spp. in plants. Phytopathology 1989, 79, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, D.C.; Ribeiro, O.K. Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1996; p. 562. ISBN 0-89054-212-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hagle, S.K. Management Guide for Laminated Root Rot. In Forest Insect and Disease Management Guide for the Northern and Central Rocky Mountains; In cooperation with the Idaho Department of Lands and the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation; Non-standard pagination; USDA Forest Service, Northern and Intermountain Regions, State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection: Missoula, MT, USA; Boise, ID, USA; Idaho Department of Lands, Forestry Division, Insects and Disease: Coeur d’Alene, ID, USA; Montana DNRC, Forestry Division, Forest Pest Management: Missoula, MT, USA, 2009; Chapter 11.2; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Keča, N.; Karadžić, D.; Woodward, S. Ecology of Armillaria species in managed forests and plantations in Serbia. For. Pathol. 2009, 39, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakys, R.; Vasiliauskas, A.; Ihrmark, K.; Stenlid, J.; Menkis, A.; Vasaitis, R. Root rot, associated fungi and their impact on health condition of declining Fraxinus excelsior stands in Lithuania. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 26, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, R.; Pharmawati, M.; Lapis-Gaza, R.H.; Rossig, C.; Berkowitz, O.; Lambers, H.; Finnegan, P.M. Differentiating phosphate-dependent and phosphate-independent systemic phosphate-starvation response networks in Arabidopsis thaliana through the application of phosphite. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2501–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muñoz, F.; Marçais, B.; Dufour, J.; Dowkiw, A. Rising out of the ashes: Additive genetic variation for crown and collar resistance to Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in Fraxinus excelsior. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percival, G.C. The use of chlorophyll fluorescence to identify chemical and environmental stress in leaf tissue of three oak (Quercus) species. J. Arboric. 2005, 31, 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Percival, G.C.; Keary, I.P.; Al-Habsi, S. An assessment of the drought tolerance of Fraxinus genotypes for urban landscape plantings. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 5, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunov, M.; Dankov, K.; Dimitrova, S.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Strasser, R.; Kalaji, H.M.; Goltsev, V. Effect of water stress on photosynthetic light phase in leaves of two ecotypes of Platanus orientalis L. plants. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, SE/ONLINE, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pšidová, E.; Živčák, M.; Stojnić, S.; Orlović, S.; Gömöry, D.; Kučerová, J.; Ditmarová, L.; Střelcová, K.; Brestič, M.; Kalaji, H.M. Altitude of origin influences the responses of PSII photochemistry to heat waves in European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 152, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollastrini, M.; Luchi, N.; Michelozzi, M.; Gerosa, G.; Marzuoli, R.; Bussotti, F.; Capretti, P. Early physiological responses of Pinus pinea L. seedlings infected by Heterobasidion sp. in an ozone-enriched atmospheric environment. Tree Physiol. 2015, 35, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fini, A.; Ferrini, F.; Frangi, P.; Amoroso, G.; Piatti, R. Withholding irrigation during the establishment phase affected growth and physiology of Norway maple (Acer platanoides) and linden (Tillia spp.). Arboric. Urban For. 2009, 35, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Steinböck, S.; Hietala, A.; Solheim, H.; Kräutler, K.; Kirisits, T. Association of Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus with leaf symptoms on Fraxinus excelsior: Phenology and pathogen colonization profile. In Proceedings of the COST ACTION FP1103 FRAXBACK 4th Management Committee meeting and workshop ‘Frontiers in ash dieback research’, Malmö, Sweden, Belgium, 4–6 September 2013; Vasaitis, R., Cleary, M.R., Eds.; [Poster]Meeting Program and Abstracts. COST: Brussels, Belgium; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bonello, P.; Gordon, T.R.; Herms, D.A.; Wood, D.L.; Erbilgin, N. Nature and ecological implications of pathogen-induced systemic resistance in conifers: A novel hypothesis. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 68, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, F.W., Jr.; Krstić, M.; Zavarin, E.; Barber, H.W., Jr. Inhibitory effecets of volatile oleoresin components on Fomes annosus and four Ceratocystis species. Phytopathology 1968, 58, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Eyles, A.; Bonello, P.; Ganley, R.; Mohammed, C. Induced resistance to pests and pathogens in trees. New Phytol. 2010, 185, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reglinski, T.; Dann, E.; Deverall, B. Implementation of Induced Resistance for Crop Protection. In Induced Resistance for Plant Defense; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 249–299, Print ISBN 978-11-183-7183-1; Online ISBN 978-11-183-7184-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey-Klett, P.; Garbaye, J. Mycorrhiza helper bacteria: A promising model for the genomic analysis of fungal-bacterial interactions. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mock Inoculation and Control | Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (Hf) | Phytophthora Mix * | H. fraxineus + Phytophthora Mix | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 80 |

| Actifos | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 80 |

| Inoculation time | No inoculation | 26 September 2016 | 10 July 2016 | 10 July 2016 26 September 2016 |

| Diameter (D) | Diff in D | Height (H) | Diff in H | Shoot/Root Dry Weight Ratio | Leaf Area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10−3 m | g | cm2 | ||||

| Water | ± | 0.41 ± 0.06 b | 114.50 ± 7.01 a | 22.70 ± 5.93 a | 0.29 ± 0.26 a | 106.47 ± 12.04 a |

| Hf | 6.07 ± 0.17 **b | 0.08 ± 0.01 d | 174.04 ± 6.69 c | 0.71 ± 0.07 d | 0.55 ± 0.47 b | 0.00 ± 0.00 c |

| Phy | 6.26 ± 0.23 a | 0.57 ± 0.14 a | 151.36 ± 6.93 c | 11.79 ± 2.38 b | 0.35 ± 0.19 ab | 65.91 ± 8.91 b |

| Hf + Phy | 6.25 ± 0.21 a | 0.16 ± 0.08 c | 171.54 ± 7.98 c | 9.29 ± 4.45 c | 0.53 ± 0.67 b | 101.09 ± 27.41 b |

| Actifos | 5.38 ± 0.19 c | 0.19 ± 0.05 c | 134.39 ± 7.46 b | 23.11 ± 7.56 a | 0.34 ± 0.17 ab | 111.31 ± 17.28 a |

| Act + Hf | 6.06 ± 0.16 b | 0.39 ± 0.07 b | 183.20 ± 8.84 d | 14.05 ± 3.17 b | 0.36 ± 0.29 ab | 91.22 ± 24.24 a |

| Act + Phy | 6.08 ± 0.20 b | 0.26 ± 0.04 b | 136.89 ± 5.65 b | 11.97 ± 1.82 b | 0.29 ± 0.21 a | 40.35 ± 9.48 b |

| Act + Hf + Phy | 5.93 ± 0.10 b | 0.40 ± 0.15 b | 150.13 ± 8.75 c | 8.65 ± 3.43 c | 0.29 ± 0.31 a | 62.76 ± 17.21 b |

| Water | Hf | Phy | Hf + Phy | Actifos | Act + Hf | Act + Phy | Act + Hf + Phy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRL (cm) | 1014.83 ± 76.44 a* | 846.93 ± 71.98 a | 1065.22 ± 61.93 a | 1541.93 ± 90.66 b | 1061.89 ± 60.16 a | 1346.74 ± 58.42 b | 941.83 ± 36.91 a | 889.81 ± 64.57 a |

| FRL (cm) | 978.85 ± 75.05 a | 793.48 ± 69.36 a | 1012.55 ± 59.24 a | 1474.27 ± 92.32 b | 1012.31 ± 58.89 a | 1268.28 ± 54.86 b | 893.9 ± 34.87 a | 842.42 ± 62.38 a |

| SA (cm2) | 173.07 ± 12.83 a | 208.34 ± 18.21 a | 217.88 ± 12.69 a | 347.37 ± 28.9 b | 207.8 ± 10.26 a | 320.72 ± 17.44 b | 194.8 ± 11.14 a | 187.12 ± 13.91 a |

| FRSA (cm2) | 97.99 ± 7.9 a | 97.49 ± 9.74 a | 113.09 ± 7.24 a | 174.16 ± 9.87 b | 115.71 ± 6.83 a | 161.98 ± 8.21 b | 105.21 ± 4.5 a | 101.32 ± 8.32 a |

| NoT (n) | 5387.95 ± 612.69 a | 3500 ± 480.15 abc | 5093.2 ± 637.52 ab | 7340.44 ± 2510.38 a | 2084.7 ± 305.99 c | 5178 ± 628.92 ab | 4016.3 ± 662.69 abc | 2494.05 ± 361.36 bc |

| FRT (n) | 5384.7 ± 612.65 a | 3496.29 ± 479.88 abc | 5087.6 ± 637.19 ab | 7334.22 ± 2510.51 a | 2081.55 ± 305.97 c | 5172.75 ± 628.81 ab | 4012.25 ± 662.24 abc | 2489.5 ± 361.08 bc |

| FRL/MRL | 43.1 ± 4.27 b | 30.56 ± 5.46 ab | 33.84 ± 2.39 ab | 32.69 ± 4.78 ab | 29.32 ± 2.53 ab | 24.73 ± 1.79 a | 24.19 ± 1.68 a | 30.3 ± 6.91 ab |

| FRT/MRL | 273.09 ± 55.7 b | 158.2 ± 39.07 ab | 165.8 ± 23.42 ab | 196.08 ± 75.8 ab | 57.08 ± 7.74 a | 105.44 ± 18.16 a | 100.4 ± 15.59 a | 84.81 ± 13.91 a |

| Parameters | Mean | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll fluorescence (159) | (1) PIabs | 0.743 | 0.065 | − | |||||||||

| (2) PItot | 1.230 | 0.893 | 0.60 ** | − | |||||||||

| (3) DI/CSo | 67.476 | 21.529 | −0.81 ** | −0.46 ** | − | ||||||||

| (4) ET/CSo | 89.500 | 24.877 | 0.53 ** | 0.68 ** | −0.05 | − | |||||||

| No. of living plants (8) | (5) Survival | 14.875 | 7.060 | −0.39 | −0.53 | 0.02 | −0.53 | − | |||||

| Growth parameters (187) | (6) Height | 141.30 | 38.94 | −0.03 | −0.16 * | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.58 | − | ||||

| (7) Diameter | 5.79 | 1.044 | −0.12 | −0.21 ** | 0.10 | −0.09 | 0.65 | 0.57 ** | − | ||||

| (8) Leaf area | 88.52 | 82.303 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.19 * | − | |||

| Chemical analysis (24) | (9) Phenols | 5.714 | 6.400 | −0.50 * | −0.11 | 0.43 * | −0.23 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.16 | −0.09 | − | |

| (10) Triterpenes | 30.615 | 21.612 | 0.24 | 0.04 | −0.25 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.31 | −0.50 * | − | |

| (11) Sterols | 12.590 | 6.260 | 0.14 | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.32 | −0.16 | −0.12 | −0.03 | −0.32 | −0.28 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keča, N.; Tkaczyk, M.; Żółciak, A.; Stocki, M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Oszako, T. Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species. Forests 2018, 9, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080442

Keča N, Tkaczyk M, Żółciak A, Stocki M, Kalaji HM, Nowakowska JA, Oszako T. Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species. Forests. 2018; 9(8):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080442

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeča, Nenad, Milosz Tkaczyk, Anna Żółciak, Marcin Stocki, Hazem M. Kalaji, Justyna A. Nowakowska, and Tomasz Oszako. 2018. "Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species" Forests 9, no. 8: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080442

APA StyleKeča, N., Tkaczyk, M., Żółciak, A., Stocki, M., Kalaji, H. M., Nowakowska, J. A., & Oszako, T. (2018). Survival of European Ash Seedlings Treated with Phosphite after Infection with the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus and Phytophthora Species. Forests, 9(8), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080442