Responsible Decision making for Sustainable Motivation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Decision Making and Human Potential Motivation

- Decision making performed in other organizational areas that indirectly affects (positively or negatively) work motivation, such as decisional processes, which result in indirect consequence-orientated decisions touching motivation;

- Decision making that intentionally and sustainably improves motivation, like a decision process which results in direct, procedurally satisfied, motivational decisions.

1.1.1. Consequentially Orientated Decisions Affecting Motivation

1.1.2. Procedurally Contented Decision Making Improving Motivation

1.2. Sustainably Responsible Motivation

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Instruments

2.2. Sample

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure—Test of Reliance

3. Data Analysis and Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Indications from Data Analysis

3.2.2. Model of Decision Making for Sustainably Responsible Motivation

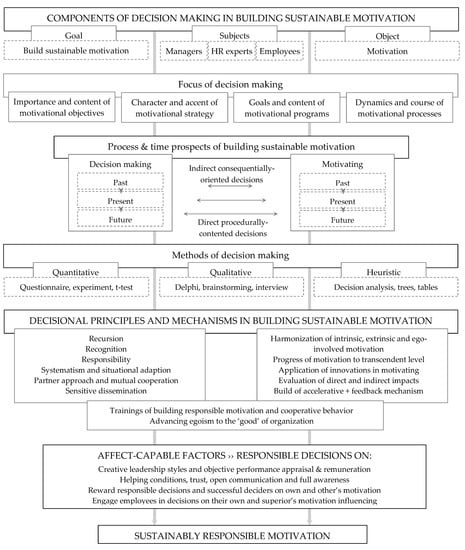

Components of Decision-Making in Building Sustainable Motivation

- Goal (to build sustainable motivation), subjects (participants in the process, such as managers, HR experts, employees, partners, etc.), and the object of decision-making (motivation);

- Focus of decision making on solving four key problems, like setting motivational objectives, working out a motivational strategy, creating motivational programs, and performing motivational processes;

- Process and time prospects of building sustainable motivation, such as mutual and accelerative relations between and among the past, present and future decision making in the area of motivation; and the past, present and future motivations and processes of motivating;

- Methods of decision making potentially usable when deciding a process of motivating individuals and groups, like a quantitative (questionnaire, experiment, t-test, …), qualitative (Delphi method, interview, brainstorming, brainwriting, etcetera.) and heuristic classes (decision analysis, decision trees, decisions tables, and more).

Decisional Principles and Mechanisms in Building Sustainable Motivation

- Application of crucial principles such as the three Rs (recursion, recognition, and responsibility), systematism and permanent situational adaptation to changed conditions, partner approach, open cooperation, sensitive application of taken motivational decisions and measures;

- Achieving the functionality of/for advanced processes of decision making and motivating, such as harmonization of all the motivations, progressing the motivation to a transcendent level, creating and implementing innovativeness in motivating, evaluation of all positive and negative impacts, development of accelerative mechanisms and mechanisms for constructive feedback;

- Building the conditions and overall possibilities for functionality of the proposed model, like training in the area of building responsible motivation, cooperative behavior, willingness and readiness of persons who affect the motivation as well as processes for advancing the individual egoism for the ‘good’ of the organization.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hohnen, P. Corporate Social Responsibility. An Implementation Guide for Business; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2007; ISBN 978-1-895536-97-3. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jereb, B.; Kukovič, D.; Cvahte, T. Lifelong learning program in university/industry partnership project Tempus RECOAUD: Training of eco-management and climate change adaptation. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Human Potential Development 2017, Szczecin, Poland, 7–9 June 2016; University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2017; pp. 101–111, ISBN 978-83-7518-782-3. [Google Scholar]

- Maletic, M.; Maletic, D.; Dahlgaard, J.; Dahlgaard, S.M.; Gomiscek, B. Do corporate sustainability practices enhance organizational economic performance? Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2015, 7, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vojáček, O.; Louda, J. Economic value of ecosystem services in the Eastern Ore Mountains. Econ. Manag. (E&M) 2017, 20, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ma, Q.; Morse, S. Motives for Corporate Social Responsibility in Chinese Food Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Barcik, A.; Dziwiński, P. The effect of the internal side of social responsibility on firm competitive success in the business services industry. Sustainability 2016, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Lee, J.; Chung, Y. Value creation mechanism of social enterprises in manufacturing industry: Empirical evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, M.; Chefneux, L.; Goldberg, A.; von Heimburg, J.; Patrignani, N.; Schofield, M.; Shilling, C. Responsible innovation: A complementary view from industry with proposals for bridging different perspectives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stýblo, J. Innovation behaviour and creativity as the way to organizational effectivity. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Human Potential Development 2017, Szczecin, Poland, 7–9 June 2016; University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2017; pp. 258–265, ISBN 978-83-7518-782-3. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.V.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, W.E.; Stibbe, A. Public health and the environment: What skills for sustainability literacy—And why? Sustainability 2009, 1, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marková, V.; Lesníková, P.; Kaščáková, A.; Vinczeová, M. The present status of sustainability concept implementation by business in selected industries in the Slovak Republic. Econ. Manag. (E&M) 2017, 20, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Agundez, I.; Onaindia, M.; Barragueta, P.; Madariaga, I. Provisioning ecosystem services supply and demand: The role of landscape management to reinforce supply and promote synergies with other ecosystem services. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovey, H. Sustainability: A platform for debate. Sustainability 2009, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Ramstad, P.M. Beyond HR: The New Science of Human Capital; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1422104156. [Google Scholar]

- Christina, S.; Dainty, A.; Daniels, K.; Tregaskis, O.; Waterson, P. Shut the fridge door! HRM alignment, job redesign and energy performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blašková, M.; Blaško, R. Sustainable development of rural tourism through relations between customers’ and employees’ motivation. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2008, 4, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management—A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Physica-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-7908-2187-1. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, M.; Boselie, P.; Brewster, C. Back to the future: Implications for the field of HRM of the multistakeholder perspective proposed 30 years ago. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosak-Szyrocka, J. Employee’s motivation at hospitals as a factor of the organization success. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2014, 8, 102–111. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- James, L.R.; Rentsch, J.R. Justify to explain the reasons why: A conditional reasoning approach to understanding motivated behavior. In Personality and Organizations; Schneider, B., Smith, D.B., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 223–250. ISBN 978-0-415-65078-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T. How to Keep Your Best People: Develop a “Level 4” Mindset in Your Line Managers. Dev. Learn. Organ. 2016, 30, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Handbook of Human Resource Practice, 8th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M. Handbook of Human Resource Practice, 10th ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Koubek, J. Personnel Work in Small and Medium-Sized Companies, 3rd ed.; Grada: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blašková, M. Human Potential Management and Development. Applying the Motivational Accent in Processes of Human Potential Development; EDIS: Žilina, Slovak Republic, 2003; ISBN 80-8070-034-6. [Google Scholar]

- Blašková, M.; Stachová, K.; Poláčková, K.; Stacho, Z.; Blaško, R. Motivation: Motivational Spirals and Decision Making; Oficyna Wydawnicza Stowarzyszenia Menedżerów Jakości i Produkcji: Czestochowa, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-63978-70-9. [Google Scholar]

- Olejniczak, K.; Majchrzak-Lepczyk, J. Social responsibility as the factor of competitive advantage of public entities. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2014, 8, 74–87. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 12 January 2018).

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Ruhe, G. Formal description of the cognitive process of decision making. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Informatics, Victoria, BC, Canada, 17 August 2004; pp. 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tepper, B.B. Managerial Knowledge and Skills; Grada Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 1996; ISBN 80-7169-347-2. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.L.; Turnbull, O.H. Affective bias in complex decision making: Modulating sensitivity to aversive feedback. Motiv. Emot. 2011, 2, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, E. Creative Solutions: How Creativity Can Help with Decision Making and Analysis. 12 December 2008. Available online: www.thinkingmanagers.com/management/creative-solutions (accessed on 19 August 2018).

- Drucker, P. The Effective Decision. Harvard Business Review on Decision Making; HBS Publishing Corporation: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Osinovskaya, I.V.; Lenkova, O.V. The technological development of managerial decisions on the productive capacity of oil producing industrial building structures. Int. Bus. Manag. 2015, 9, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, T.W. Management Science. Building and Using Models; Richard D. Irwin, Inc.: Homewood, IL, USA, 1989; ISBN 0-256-05682-X. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J.A.; Pearce, M.R.; Burgoyne, D.G.; Erskin, J.A.; Mimick, R.H. Introduction to Business Decision Making, 3rd ed.; Scarborough: Nelson, BC, Canada, 1988; ISBN 0-17-603449-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, R.S.; Brooks, M.E. Individual Differences in Decision making Skill and Style. In Judgment and Decision Making at Work; Highhouse, S., Dalal, R.S., Salas, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 80–101. ISBN 978-1-138-80171-4. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Blašková, M.; Blaško, R. Intentional versus unintentional decision making in motivating. In Proceedings of the Monograph from International Conference Toyotarity in the European Culture, Ustroń Jaszowiec, Poland, 4–6 December 2015; pp. 49–62, ISBN 978-83-63978-25-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambuu, U.; Tapiero, C.S. Globalization, Gating, and Risk Finance; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-11-19252-68-9. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Gücbilmez, I.U.; Pawlina, G. A Theory of Loan Commitments Based on the Borrower’s Investment Incentives; Lancaster University Management School: Lancaster, UK, 2009; Available online: http://www.realoptions.org/papers2009/41.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Van der Westhuizen, B. Antecedents, outcomes and personal factor used by sales managers to assess the performance of salespeople. In Proceedings of the 1993 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 26–29 May 1993; Levy, M., Grewal, D., Eds.; Springer Science + B.M.: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 317–321, ISBN 978-3-319-13158-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sokół, A. Diagnosis of intellectual capital in macroeconomic terms on the example of Szczecin and opportunities for development of creative sector. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2017, 11, 59–75. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 28 January 2018).

- Rosak-Szyrocka, J. Human resource management in Kaizen aspect. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2017, 11, 80–92. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 18 February 2018).

- Carnall, C.A. Managing Change in Organizations; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1990; ISBN 0-13-551862-8. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M. A Handbook of Employee Reward Management and Practice, 2nd ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Driskel, T.; Driskell, J.E.; Salas, E. Stress, performance and decision making in organizations. In Judgment and Decision Making at Work; Highhouse, S., Dalal, R.S., Salas, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 251–276. ISBN 978-1-138-80171-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, S.; Jackson, T. Organizational Behavior; Grada: Prague, Czech Republic, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kachaňáková, A. Human Resources Management; Sprint, vfra: Bratislava, Slovak Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, E.G. Quality decision management—The heart of effective futures-oriented management. In Topics in Safety, Risk, Reliability and Quality; Springer Science + Business Media B. V.: Berlin, Germany, 2008; Volume 14, ISBN 978-90-481-8048-6. [Google Scholar]

- Blašková, M.; Poláčková, K. Managerial decision making in motivate as support for safe and ethical behaviour at public universities. Public Secur. Public Order 2018, 20, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Albers, H.H. Principles of Management. A Modern Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Blašková, M. Human Potential Development. Motivating, Communicating, Harmonizing and Decision Making; EDIS: Žilina, Slovak Republic, 2011; ISBN 978-80-554-0430-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barbuto, J.E. Motivation and transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership. A test of antecedents. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2005, 11, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wicks, J.; Scharmer, C.O.; Pavlovich, K. Exploring Transcendental Leadership: A Conversation. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2015, 12, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, G.; Mardani, A.; Senin, A.A.; Wong, K.Z.; Sadeghi, L.; Najmi, M.; Shaharoun, A.M. Relationship between culture of excellence and organizational performance in Iranian manufacturing companies. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2016, 27, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacho, Z.; Urbancová, H.; Stachová, K. Organizational arrangement of human resources management in organizations operating in Slovakia and Czech Republic. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 2013, 61, 2787–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, I. Organisational Behaviour; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blaško, R. Teaching mathematics at university and removing mathematics anxiety: Theoretical and empirical examination. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Human Potential Development 2017, Prague, Czech Republic, 6–8 June 2017; Institute for Public Administration Prague: Nové Město, Czechia; pp. 7–17, ISBN 978-80-86976-41-9. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Kramer, S.J. What really motivates workers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, January–February, 44–45. Available online: http://hbr.org/2010/01/the-hbr-list-breakthrough-ideas-for-2010/ar/1 (accessed on 9 March 2016).

- Figurska, I. Dignity management as a new approach to human resources management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2017, 11, 23–37. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 24 January 2018).

- Kulkarni, S.M. A review on intrinsic motivation: A key to sustainable and effective leadership. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2015, 4, 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E.T.; Cornwell, J.F.M.; Franks, B. “Happiness” and “the good life” as motives working together effectively. Adv. Motiv. Sci. 2014, 1, 135–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Hilper, J.C. The balanced measure of psychological needs (BMPN) scale: An alternative domain general measure of need satisfaction. Motiv. Emot. 2012, 36, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, D.; Tokdemir, O.B.; Suh, K. Effect of learning on line-of-balance scheduling. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2001, 19, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Brueller, D.; Dutton, J.E. Learning Behaviours in the Workplace: The Role of High-quality Interpersonal Relationships and Psychological Safety. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2008, 26, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaløy, O.; Schöttner, A. Incentives to motivate. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 116, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, F. Case method and transcendent motivations. Int. J. Case Method Res. Appl. 2006, XVIII, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D.S.; Henderson, M.D.; D’Mello, S.; Paunesku, D.; Walton, G.M.; Spitzer, B.J.; Duckworth, A.L. Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, A.H. Toward a Psychology of Being, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-29309-5. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Ramstad, P.M. Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, K.B. Sustainability and pathways for implementation. In Handbook of Performability Engineering; Misra, K.B., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2008; pp. 857–874. ISBN 978-1-84800-130-5. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B.; Steiner, G.A. Human Behavior: An Inventory of Scientific Findings; Harcourt, Brace & World: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, L. Motivation. Biological, Psychological, and Environmental, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, J. Understanding Motivation and Emotion, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Milkovich, G.T.; BoudreauF, J.W. Personnel/Human Resource Management. A Diagnostic Approach, 5th ed.; BPI, Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen, J.; Heckhausen, H. Motivation und handeln: Einführung und überblick; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; ISBN 978-3-540-29975-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stombach, T.; Strang, S.; Partk, S.Q.; Kenning, P. Common and distinctive approaches to motivation in different disciplines. In Progress in Brain Research, 229: Motivation—Theory, Neurobiology and Applications; Studer, B., Knecht, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 3–23. ISBN 97-0-044-63701-7. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: Delhi, India, 1987; ISBN 978-0060419875. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer, R.; Chen, G. Motivation in organizational behavior: History, advances and prospects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blašková, M. Attributes of decision making in motivating employees. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2016, 10, 23–37. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- Blašková, M.; Bízik, M.; Jankal, R. Model of decision making in motivating employees and managers. Eng. Econ. 2015, 26, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, A.; Van Hiel, A.; Kruglanski, A.W. When motivation backfires: Optimal levels of motivation as a function of cognitive capacity in information relevance perception and social judgment. Motiv. Emot. 2013, 37, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kanfer, R. Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior. Res. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 223–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. Effective Manager, 2nd ed.; Management Press: Prague, Czech Republic, 1992; ISBN 80-85603-02-0. [Google Scholar]

- Matuska, E. Human Resources Management in a Modern Company; Higher School of Administration and Business of E. Kwiatkowski: Gdynia, Poland, 2014; ISBN 978-83-64505-45-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mathe, H.; Pavie, X.; O’Keeffe, M. Valuing People to Create Value. An Innovative Approach to Leveraging Motivation at Work; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 13-978-981-4365-06-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aldag, R.J.; Kuzuhara, L.W. Creating High Performance Teams; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA; ISBN 978-0-415-53491-8.

- Finke, I.; Will, M. Motivation for knowledge management. In Knowledge Management, 2nd ed.; Mertins, K., Heisig, P., Vorbeck, J., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 66–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. The history of self-determination theory in psychology and management. In The Oxford Handbook of Work Engagement, Motivation, and Self-Determination Theory; Gagne, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Gagné, M. Employee engagement form a self-determination theory perspective. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 1, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blašková, M.; Hitka, M.; Blaško, R.; Borkowski, S.; Rosak, J.; Križanová, A.; Farkašová, V. Management and Development of High-Qualified Human Potential; Technical University: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2006; ISBN 80-228-1701-5. [Google Scholar]

- Index Mundi—Poland & Lithuania. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/factbook/compare/poland.lithuania (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Index Mundi—Slovakia & Lithuania. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/factbook/compare/poland.lithuania (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Country Economy. Available online: https://www.indexmundi.com/factbook/compare/poland.lithuania (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Raosoft. Software for Statistical Calculation. Available online: www.raosoft (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- Lamoš, F.; Potocký, R. Probability and Mathematical Statistics. Statistical Analyses; Alfa: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1989; ISBN 80-05-00115-0. [Google Scholar]

- Likeš, J.; Machek, J. Mathematical Statistics; SNTL: Prague, Czech Republic, 1983; ISBN 04-008-83. [Google Scholar]

- Zvára, K.; Štěpán, J. Probability and Mathematical Statistics; Charles University: Prague, Czech Republic, 1997; ISBN 80-85863-24-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zsolnai, L. Responsible decision making. In Praxiology: The International Annual of Practical Philosophy and Methodology; Translation Publishers: Moncton, NB, Canada, 2008; Volume 16, ISBN 978-1-4128-0818-7. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, D.; Sieber, S. Employees, sustainability and motivation: Increasing employee engagement by addressing sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 6, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palomino, J.A.H.; Medina, J.J.E.; Arellano, M.A. Differences in motivators and values in the work of maquiladora industry employees. Contaduría y Administración 2016, 61, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cewińska, J.; Striker, M. Lifestyle as a determinant of managerial decisions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2018, 12, 47–58. Available online: http://frcatel.fri.uniza.sk/hrme/archi-sk.html (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Bučková, J. Corporate culture as an important factor in the implementary of knowledge management. AD ALTA J. Interdiscip. Res. 2017, 2, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Details | Slovakia | Lithuania | Poland |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age | Male | 38.8 | 39.7 | 39.0 |

| Female | 42.3 | 47.1 | 42.4 | |

| Total | 40.5 | 43.7 | 40.7 | |

| Birth rate | Births/1000 pop. | 9.7 | 9.9 | 9.5 |

| Life expectancy at birth | Male | 73.7 | 69.7 | 73.9 |

| Female | 81.1 | 80.7 | 81.8 | |

| Total | 77.3 | 75.0 | 77.8 | |

| GDP—per capita (PPP) | $ | 32.9 | 31.9 | 29.3 |

| Production growth rate | % | 3.5 | 2.8 | 4.2 |

| Unemployment rate | % | 7.7 | 6.7 | 4.5 |

| Age | Slovakia (n = 500) | Poland (n = 390) | Lithuania (n = 226) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees 80% | Managers 20% | Employees 88% | Managers 12% | Employees 73% | Managers 27% | |||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 18–28 | 39 | 132 | 12 | 11 | 34 | 172 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 1 |

| 29–39 | 47 | 72 | 9 | 16 | 21 | 75 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 34 | 1 | 4 |

| 40–50 | 27 | 44 | 27 | 19 | 7 | 27 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 38 | 6 | 20 |

| 51–61 | 16 | 19 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 38 | 5 | 18 |

| 61> | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 133 | 267 | 52 | 48 | 62 | 280 | 18 | 30 | 38 | 128 | 14 | 46 |

| Characteristics | Processes/Motivational Focuses | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted | Cronbach’s Alpha | n of Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group—Processes | Awareness | 0.568 | 0.835 | - | - |

| Appraisal | 0.712 | 0.795 | - | - | |

| Communication | 0.742 | 0.779 | - | - | |

| Atmosphere | 0.724 | 0.786 | - | - | |

| Total | 0.846 | 4 | |||

| Group—Motivation orientation | Quality work | 0.730 | 0.879 | - | - |

| Improve of skills | 0.761 | 0.867 | - | - | |

| New ideas | 0.796 | 0.854 | - | - | |

| Cooperation with superior | 0.788 | 0.857 | - | - | |

| Total | 0.895 | 4 | |||

| Slovakia | Poland | Lithuania | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation Focus | Degree of Motivation | Employees n = 400 | Managers n = 100 | Employees n = 342 | Managers n = 48 | Employees n = 166 | Managers n = 60 | ||||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | ||

| Motivation to quality work | High | 167 | 41.75 | 61 | 61.00 | 116 | 33.92 | 28 | 58.33 | 48 | 28.92 | 30 | 50.00 |

| Rather high | 156 | 39.00 | 30 | 30.00 | 154 | 45.03 | 17 | 35.42 | 70 | 42.17 | 23 | 38.33 | |

| Average | 47 | 11.75 | 9 | 9.00 | 59 | 17.25 | 3 | 6.25 | 39 | 23.49 | 6 | 10.00 | |

| Rather low | 21 | 5.25 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 1.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 1.81 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Low | 9 | 2.25 | 0 | 0.00 | 9 | 2.63 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 3.61 | 1 | 1.67 | |

| Mean | 1.87 | 1.48 | 1.94 | 1.49 | 2.09 | 1.65 | |||||||

| Standard deviation | 0.97 | 0.66 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 0.80 | |||||||

| Motivation to improve knowledge and skills | High | 130 | 32.50 | 53 | 53.00 | 138 | 40.35 | 30 | 62.50 | 39 | 23.49 | 18 | 30.00 |

| Rather high | 165 | 41.25 | 31 | 31.00 | 128 | 37.43 | 12 | 25.00 | 73 | 43.98 | 30 | 50.00 | |

| Average | 66 | 16.50 | 14 | 14.00 | 61 | 17.84 | 6 | 12.50 | 39 | 23.49 | 9 | 15.00 | |

| Rather low | 23 | 5.75 | 2 | 2.00 | 5 | 1.46 | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 4.82 | 2 | 3.33 | |

| Low | 16 | 4.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 10 | 2.92 | 0 | 0.00 | 7 | 4.22 | 1 | 1.67 | |

| Mean | 2.08 | 1.65 | 1.90 | 1.53 | 2.22 | 1.97 | |||||||

| Standard deviation | 1.04 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.86 | |||||||

| Motivation to new ideas | High | 64 | 16.00 | 30 | 30.00 | 80 | 23.39 | 17 | 35.42 | 22 | 13.25 | 21 | 35.00 |

| Rather high | 161 | 40.25 | 51 | 51.00 | 157 | 45.91 | 28 | 58.33 | 63 | 37.95 | 24 | 40.00 | |

| Average | 122 | 30.50 | 14 | 14.00 | 77 | 22.51 | 2 | 4.17 | 56 | 33.73 | 13 | 21.67 | |

| Rather low | 30 | 7.50 | 3 | 3.00 | 16 | 4.68 | 1 | 2.08 | 16 | 9.64 | 1 | 1.67 | |

| Low | 23 | 5.75 | 2 | 2.00 | 12 | 3.51 | 0 | 0.00 | 9 | 5.42 | 1 | 1.67 | |

| Mean | 2.47 | 1.96 | 2.21 | 1.78 | 2.56 | 1.95 | |||||||

| Standard deviation | 1.03 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 1.02 | 0.89 | |||||||

| Motivation to cooperate with superior | High | 79 | 19.75 | 45 | 45.00 | 86 | 25.15 | 18 | 37.50 | 25 | 15.06 | 17 | 28.33 |

| Rather high | 162 | 40.50 | 41 | 41.00 | 143 | 41.81 | 21 | 43.75 | 53 | 31.93 | 27 | 45.00 | |

| Average | 103 | 25.75 | 10 | 10.00 | 87 | 25.44 | 9 | 18.75 | 60 | 36.14 | 13 | 21.67 | |

| Rather low | 39 | 9.75 | 3 | 3.00 | 11 | 3.22 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 9.64 | 2 | 3.33 | |

| Low | 17 | 4.25 | 1 | 1.00 | 15 | 4.39 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 7.23 | 1 | 1.67 | |

| Mean | 2.38 | 1.74 | 2.21 | 1.80 | 2.62 | 2.05 | |||||||

| Standard deviation | 1.04 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.08 | 0.89 | |||||||

| Motivation Focus | Tested Characteristics | Leadership | Appraisal | Communication | Trust | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK | PL | LT | SK | PL | LT | SK | PL | LT | SK | PL | LT | ||

| Degree of freedom (table chi-square coefficient at significant level 0.05) | 8 (15.507) | 16 (26.296) | 16 (26.296) | 16 (26.296) | |||||||||

| Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Motivation to quality work | Pearson Chi-Square | 76.502 | 49.277 | 27.259 | 227.841 | 93.941 | 113.114 | 132.999 | 108.679 | 100.760 | 192.656 | 105.196 | 67.341 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 77.817 | 49.864 | 29.724 | 150.494 | 75.214 | 68.634 | 104.557 | 86.610 | 64.676 | 156.734 | 91.155 | 56.149 | |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 62.014 | 31.959 | 23.986 | 117.342 | 52.218 | 51.544 | 77.966 | 63.040 | 44.559 | 121.982 | 75.168 | 39.608 | |

| n of Valid Cases (value) | 500 | 383 | 211 | 500 | 381 | 214 | 500 | 380 | 213 | 500 | 385 | 215 | |

| Motivation to improve knowledge and skills | Pearson Chi-Square | 70.414 | 44.438 | 26.160 | 182.444 | 47.528 | 130.988 | 147.951 | 78.157 | 123.583 | 134.709 | 62.804 | 75.270 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 76.053 | 43.355 | 26.358 | 141.683 | 41.139 | 85.350 | 110.797 | 60.815 | 92.932 | 122.861 | 51.258 | 62.839 | |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 57.202 | 34.573 | 21.281 | 97.868 | 27.876 | 50.692 | 80.198 | 36.939 | 55.466 | 90.640 | 35.138 | 41.292 | |

| n of Valid Cases (value) | 500 | 380 | 211 | 500 | 378 | 214 | 500 | 377 | 213 | 500 | 382 | 215 | |

| Motivation to new suggestions | Pearson Chi-Square | 107.518 | 64.072 | 33.297 | 218.369 | 81.665 | 114.600 | 193.217 | 101.609 | 124.140 | 198.136 | 107.724 | 72.654 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 117.239 | 64.998 | 32.768 | 159.314 | 66.133 | 81.884 | 147.854 | 76.117 | 98.017 | 167.868 | 92.705 | 67.446 | |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 95.708 | 58.313 | 28.099 | 109.434 | 53.111 | 52.873 | 100.283 | 56.843 | 62.208 | 119.342 | 75.298 | 51.942 | |

| n of Valid Cases (value) | 500 | 379 | 207 | 500 | 377 | 210 | 500 | 376 | 209 | 500 | 381 | 211 | |

| Motivation to cooperate with superior | Pearson Chi-Square | 133.091 | 76.258 | 53.207 | 291.071 | 132.533 | 131.040 | 174.370 | 189.949 | 144.366 | 274.270 | 135.398 | 124.884 |

| Likelihood Ratio | 142.405 | 76.230 | 49.161 | 201.736 | 91.280 | 100.348 | 134.894 | 119.407 | 113.727 | 231.467 | 117.453 | 107.303 | |

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 114.184 | 68.414 | 39.229 | 148.862 | 81.020 | 73.449 | 104.392 | 91.098 | 65.955 | 174.604 | 103.385 | 73.152 | |

| n of Valid Cases (value) * | 500 | 381 | 210 | 500 | 379 | 213 | 500 | 378 | 212 | 500 | 383 | 214 | |

| Factor of Change | Mean of ALL | Mean of SK | Mean of PL | Mean of LT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant success in the work area | 29.40% | 34.60% | 31.03% | 22.57% |

| Big failure in work | 6.03% | 5.00% | 10.00% | 3.10% |

| Experience of joyful, pursuing event | 9.15% | 6.40% | 8.21% | 12.83% |

| The success and happiness of a child | 9.03% | 4.20% | 10.51% | 12.39% |

| Slow maturation and own development | 20.54% | 11.20% | 43.33% | 7.08% |

| Satisfaction in partner life | 15.00% | 19.60% | 12.56% | 12.83% |

| Meeting recognized, respected man | 11.07% | 12.40% | 9.74% | 11.06% |

| Achieving a long-desired goal | 26.76% | 32.20% | 26.41% | 21.68% |

| Starting a family | 22.44% | 44.40% | 17.18% | 5.75% |

| Death of a loved one or friend | 8.84% | 18.00% | 7.18% | 1.33% |

| Arising the hidden, latent need | 11.68% | 25.40% | 7.44% | 2.21% |

| Long-term fatigue, stress, burn-out | 17.71% | 1.40% | 28.72% | 23.01% |

| Awareness of own qualities | 27.66% | 11.20% | 44.36% | 27.43% |

| Demotivating influence of superior | 12.36% | 4.00% | 15.38% | 17.70% |

| Failure, unfortunate of the child | 11.76% | 31.40% | 2.56% | 1.33% |

| Disappointment in partner life | 13.07% | 30.60% | 4.62% | 3.98% |

| Change of job or employment | 21.46% | 14.80% | 29.23% | 20.35% |

| Health and state of health | 25.16% | 25.40% | 23.08% | 26.99% |

| Characteristics | SK vs. PL | SK vs. LT | SK vs. All | PL vs. LT | PL vs. All | LT vs. All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive sum | 87 | 113 | 140 | 99 | 92 | 40 |

| Negative sum | −84 | −58 | −31 | −72 | −79 | −131 |

| Test statistics | 84 | 58 | 31 | 72 | 79 | 40 |

| Confirmed hypothesis | H1 | H1 | H0 | H1 | H1 | H0 |

| Suggestions | Slovakia | Poland | Lithuania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | Managers | Employees | Managers | Employees | Managers | |||||||

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | |

| Greater interest in employees | 184 | 46.00 | 38 | 38.00 | 157 | 45.91 | 24 | 50.00 | 65 | 39.16 | 22 | 36.67 |

| Training activities and skills development | 131 | 32.75 | 25 | 25.00 | 147 | 42.98 | 15 | 31.25 | 13 | 7.83 | 4 | 6.67 |

| Creating good relationship | 121 | 30.25 | 33 | 33.00 | 165 | 48.25 | 20 | 41.67 | 90 | 54.22 | 29 | 48.33 |

| Higher remuneration and rewards | 160 | 40.00 | 40 | 40.00 | 251 | 73.39 | 26 | 54.17 | 97 | 58.43 | 26 | 43.33 |

| Career growth and job prospects | 176 | 44.00 | 32 | 32.00 | 157 | 45.91 | 18 | 37.50 | 60 | 36.14 | 21 | 35.00 |

| Participation in decisions | 76 | 19.00 | 20 | 20.00 | 56 | 16.37 | 11 | 22.92 | 30 | 18.07 | 11 | 18.33 |

| Fairness, justice and humanity of superior | 310 | 77.50 | 66 | 66.00 | 168 | 49.12 | 22 | 45.83 | 76 | 45.78 | 23 | 38.33 |

| Providing the necessary information | 137 | 34.25 | 23 | 23.00 | 86 | 25.15 | 5 | 10.42 | 41 | 24.70 | 11 | 18.33 |

| Mutual and open cooperation | 191 | 47.75 | 40 | 40.00 | 156 | 45.61 | 18 | 37.50 | 70 | 42.17 | 27 | 45.00 |

| Space for autonomy and self-realization | 166 | 41.50 | 36 | 36.00 | 77 | 22.51 | 12 | 25.00 | 35 | 21.08 | 12 | 20.00 |

| Better work conditions | 56 | 14.00 | 23 | 23.00 | 137 | 40.06 | 13 | 27.08 | 40 | 24.10 | 11 | 18.33 |

| Recognition for quality work | 225 | 56.25 | 43 | 43.00 | 122 | 35.67 | 13 | 27.08 | 35 | 21.08 | 15 | 25.00 |

| Employee bonuses and benefits | 191 | 47.75 | 34 | 34.00 | 126 | 36.84 | 7 | 14.58 | 67 | 40.36 | 22 | 36.67 |

| Improving mutual communication | 135 | 33.75 | 27 | 27.00 | 111 | 32.46 | 18 | 37.50 | 45 | 27.11 | 17 | 28.33 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blašková, M.; Figurska, I.; Adamoniene, R.; Poláčková, K.; Blaško, R. Responsible Decision making for Sustainable Motivation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103393

Blašková M, Figurska I, Adamoniene R, Poláčková K, Blaško R. Responsible Decision making for Sustainable Motivation. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103393

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlašková, Martina, Irena Figurska, Ruta Adamoniene, Kristína Poláčková, and Rudolf Blaško. 2018. "Responsible Decision making for Sustainable Motivation" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103393