Natural Resources Curse in the Long Run? Bolivia, Chile and Peru in the Nordic Countries’ Mirror

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sources and Methods

3. Results

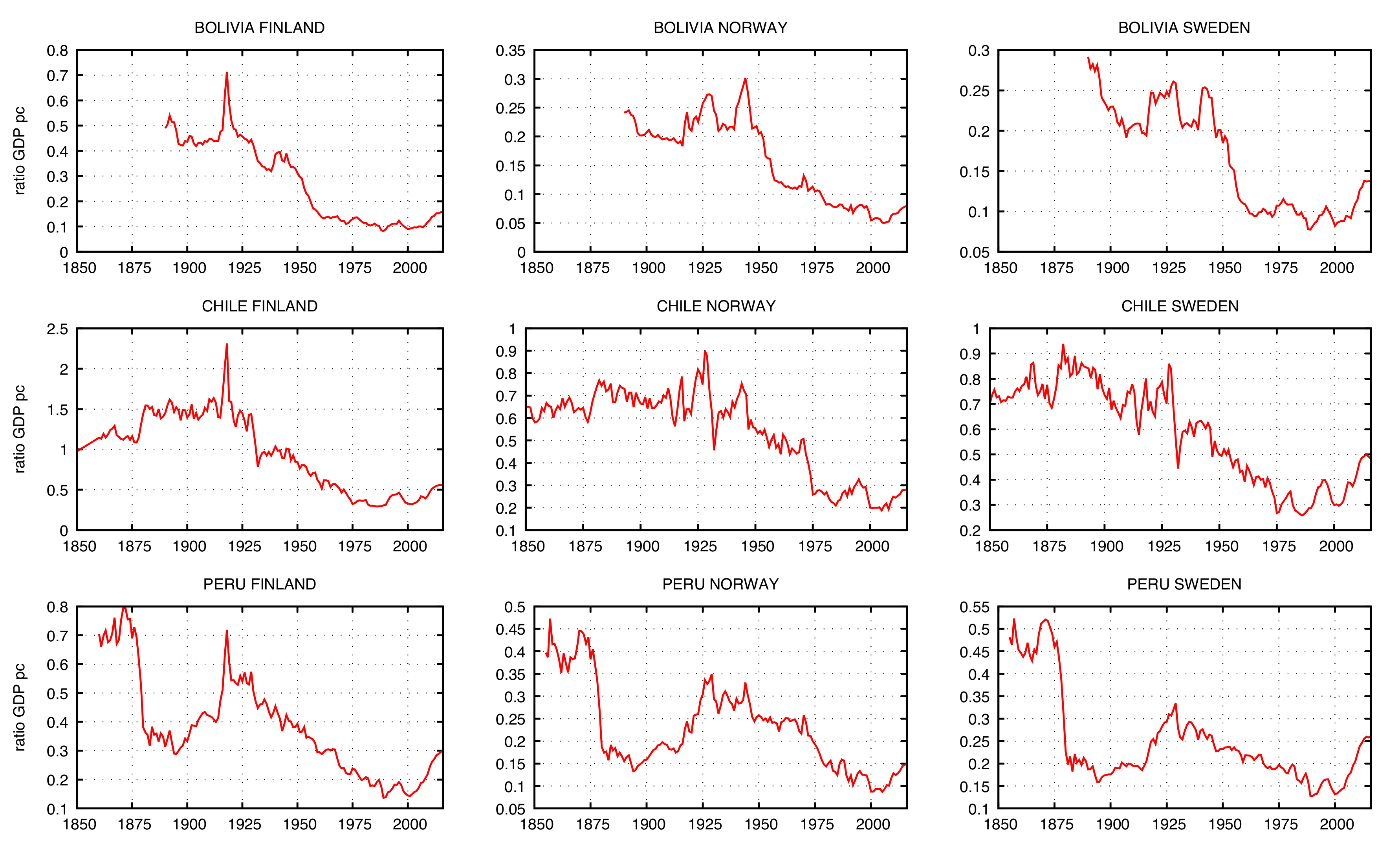

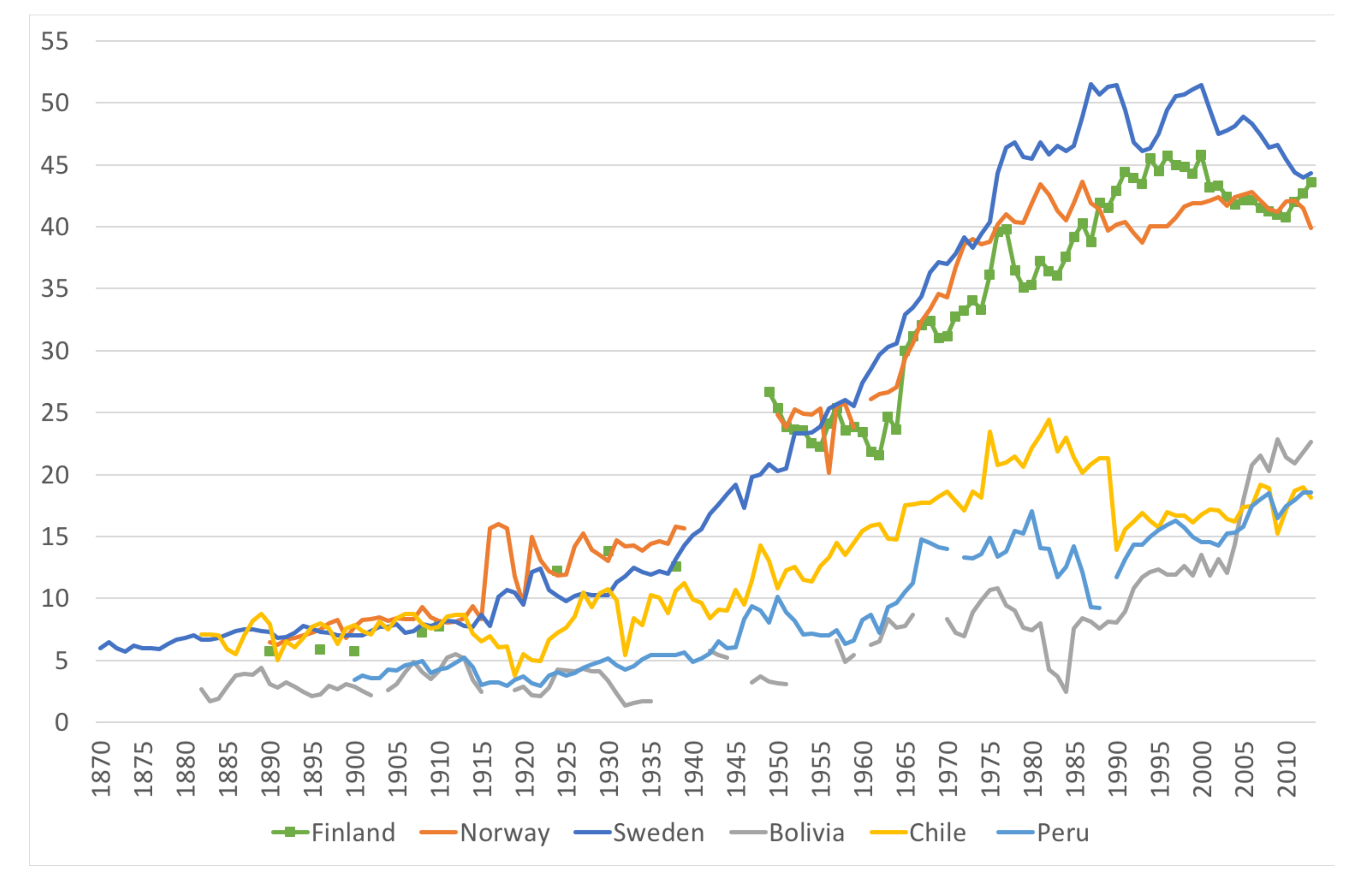

3.1. Long-Term Economic Growth

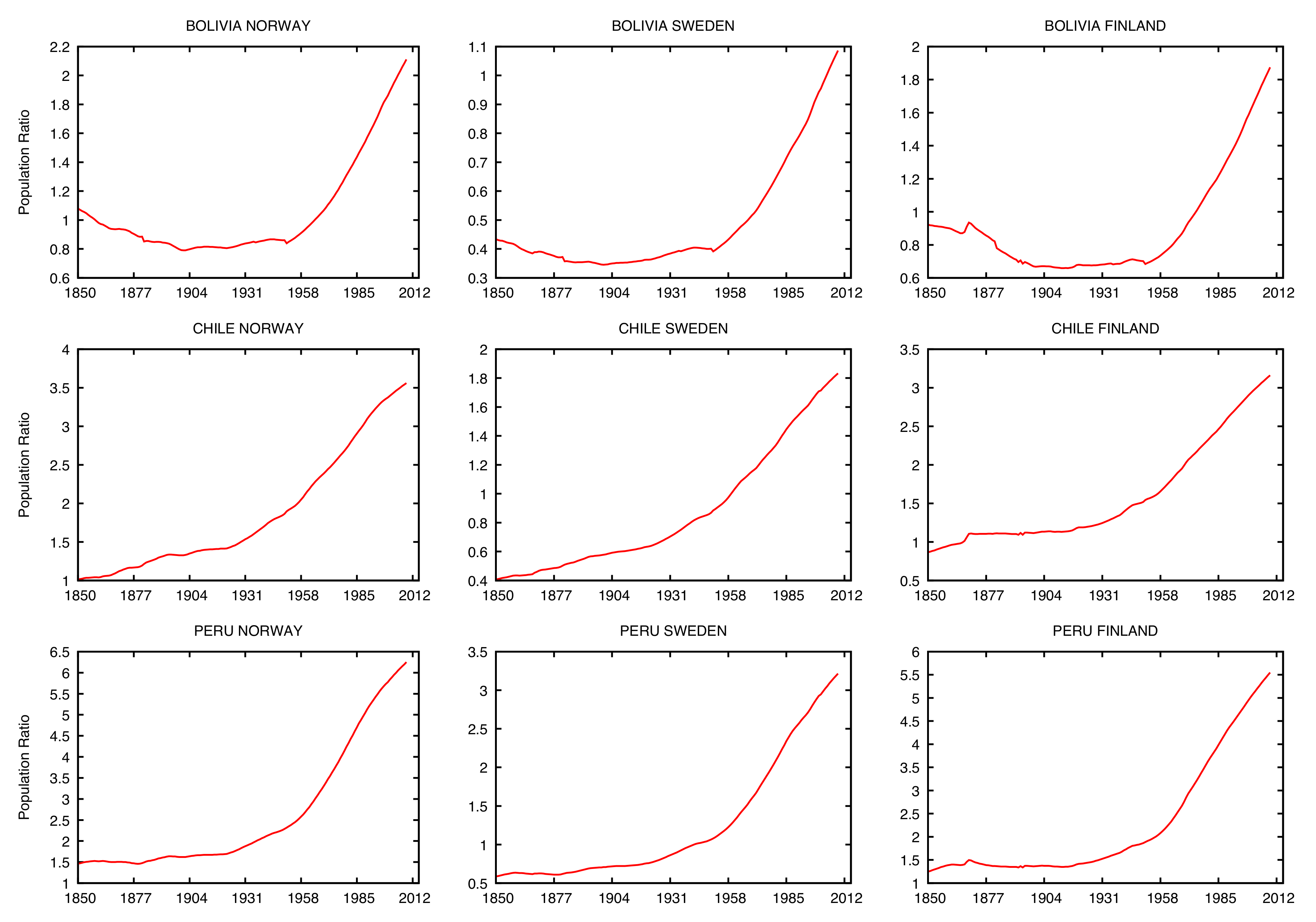

3.2. Economic Divergence

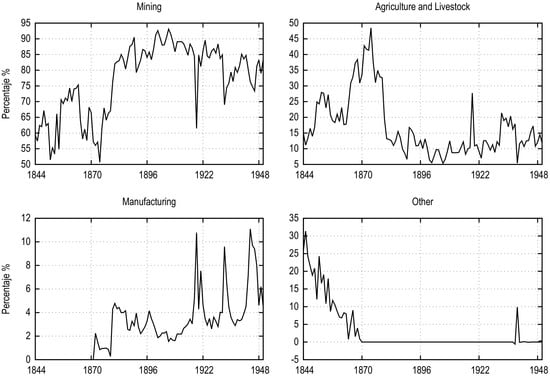

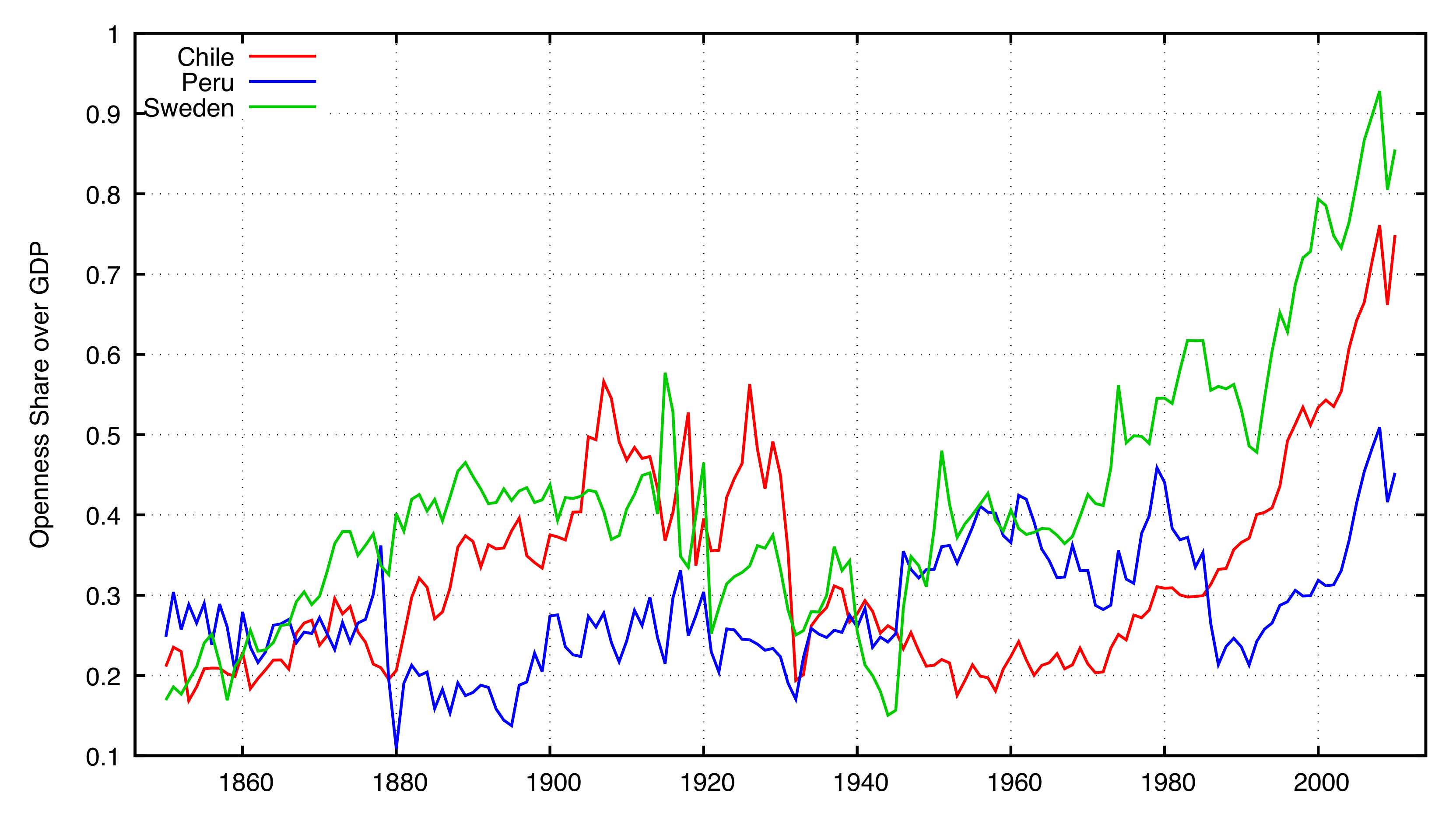

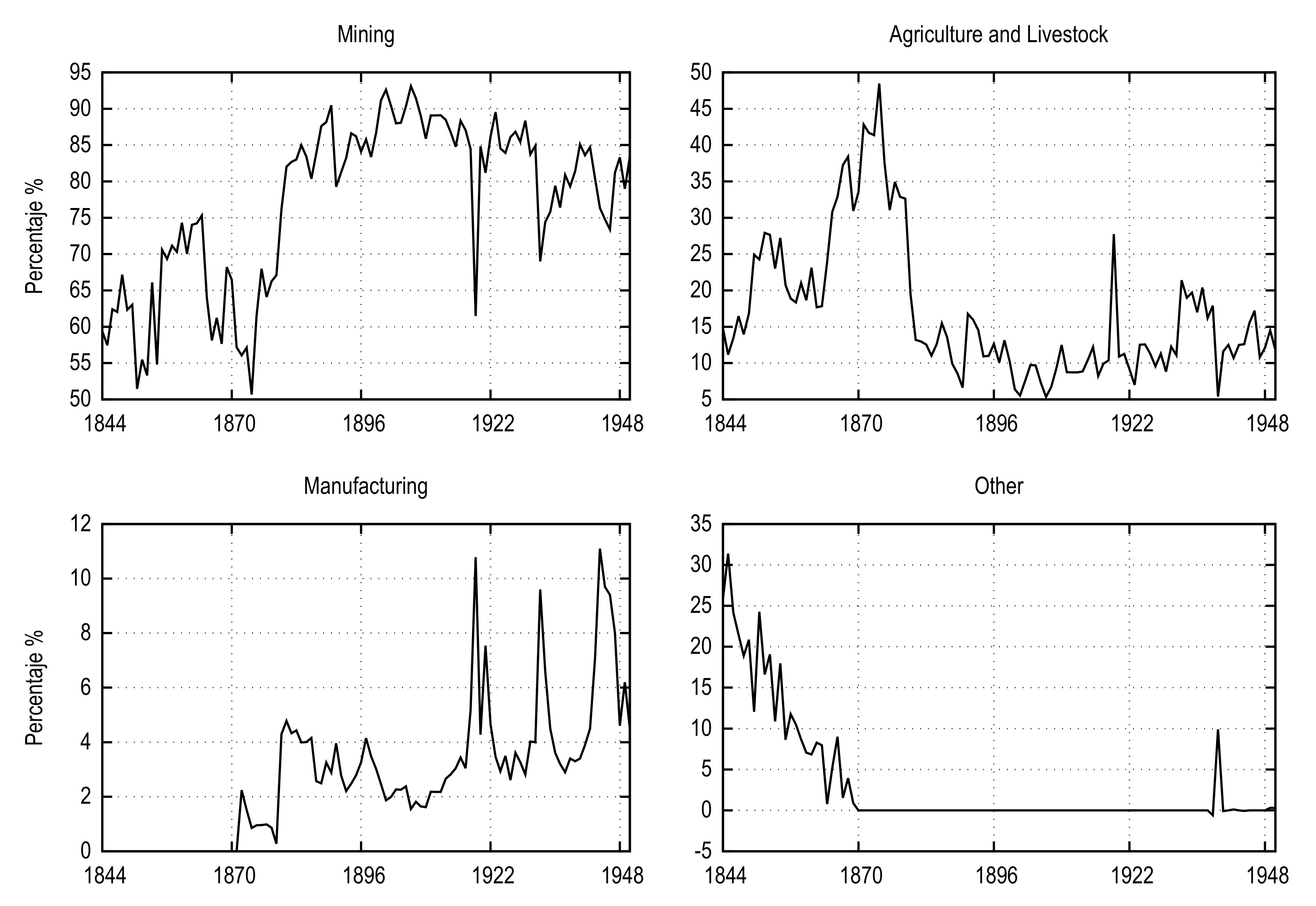

3.3. Trade Evolution and Industrial Development

3.3.1. Trade

3.3.2. Industry

3.4. A Knowledge Gap

3.5. Fiscal Policy

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Auty, R.M. Sustaining development in mineral economies: The resource curse thesis. Resour. Policy 1993, 20, 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. Natural resource abundance and economic growth. HIID Work. Pap. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. The curse of natural resources. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylfason, T. Natural resources, education, and economic development. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2001, 45, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylfason, T. The International Economics of Natural Resources and Growth; CESifo Working Paper Series No. 1994; CESifo: Munich, Germany, 11 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R.M. Natural resource endowment, the state and development strategy. J. Int. Dev. 1997, 9, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattman, C.; Hwang, J.; Williamson, J.G. Winners and losers in the commodity lottery: The impact of terms of trade growth and volatility in the Periphery 1870–1939. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 82, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ploeg, F.; Venables, A.J. Harnessing Windfall Revenues: Optimal Policies for Resource-Rich Developing Economies. Econ. J. 2011, 121, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenwurcel, G.; Katz, S. La economía política de los recursos naturales en América del Sur. Rev. Integr. Comer. 2012, 35, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Willebald, H.; Badia-Miró, M.; Pinilla, V. Introduction: Natural resources and economic development. What can we learn from history? In Natural Resources and Economic Growth: Learning from History; Badia-Miró, M., Pinilla, V., Willebald, H., Eds.; Economic History, Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, J.G. Industrial Catching up in the Poor Periphery 1870–1975. CEPR Discuss. Pap. 2011, 16809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Hoeffler, A. Resource Rents, Governance, and Conflict. J. Confl. Resolut. 2005, 49, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papyrakis, E.; Gerlagh, R. The resource curse hypothesis and its transmission channels. J. Comp. Econ. 2004, 32, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J.A. The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey; NBER Working Paper No. 15836; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, A.J. Using Natural Resources for Development: Why Has It Proven So Difficult? J. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 30, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnott, E.; Nash, J.; Torre, A.D. America and the Caribbean beyond Booms and Busts? World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Hujo, K.; McClanahan, S. Financing Social Policy: Mobilizing Resources for Social Development; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009; p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, P. Fiscal Policy and the Natural Resources Curse: How to Escape from the Poverty Trap; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. The resource curse exorcised: Evidence from a panel of countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 116, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschini, A.D.; Pettersson, J.; Roine, J. The Resource Curse and its Potential Reversal. World Dev. 2013, 43, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnschweiler, C.N.; Bulte, E.H. The resource curse revisited and revised: A tale of paradoxes and red herrings. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, S.S.; Menaldo, V. Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism? A Reappraisal of the Resource Curse. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2011, 105, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferranti, D.; Perry, G.; Lederman, D.; Maloney, W. From Natural Resources to the Knowledge Economy: Trade and Job Quality; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stijns, J.P.C. Natural resource abundance and economic growth revisited. Resour. Policy 2005, 30, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, E.A. Energy and the Industrial Revolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, G. The USA as a Case Study in Resource-Based Development. In Natural Resources and Economic Growth: Learning from History; Badia-Miró, M., Pinilla, V., Willebald, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ville, S.; Dean, P.; Wicken, O. Dynamic Natural Resource Paths of Economic Development in Australia and Norway since 1950. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hillbom, E. Cattle, diamonds and institutions: Main drivers of Botswana’s economic development, 1850 to present. J. Int. Dev. 2014, 26, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillbom, E. Botswana: Caught in a natural trap. In Natural Resources and Economic Growth: Learning from History; Badia-Miró, M., Pinilla, V., Willebald, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz-Loncán, A.; Peres-Cajías, J.A.J. Tracing the reversal of fortune in the Americas: Bolivian GDP per capita since the mid-nineteenth Century. Cliometrica 2015, 10, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, J.; van Zanden, J.L. The Maddison Project: Collaborative research on historical national accounts. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2014, 67, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomström, M.; Meller, P. Diverging Paths: Comparing a Century of Scandinavian and Latin American Economic Development; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Ranestad, K. The mining sectors in Chile and Norway, ca. 1870–1940: The development of a knowledge gap. Innov. Dev. 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadberry, S.; Wallis, J.J. Growing, Shrinking, and Long Run Economic Performance: Historical Perspectives on Economic Development; NBER Working Paper No. 23343; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bolt, J.; Inklaar, R.; de Jong, H.; van Zanden, J.L. Maddison Project Database, Version 2018. Rebasing ‘Maddison’: New Income Comparisons and the Shape of Long-Run Economic Development; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De la Escosura, L. When did Latin America fall behind? In The Decline of Latin American Economies: Growth, Institutions, and Crises. NBER-Conference Report; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.S. A Concise History of Bolivia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 2, p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Mitre, A. Los Patriarcas de la Plata: Estructura Socioeconómica de la Mineria Boliviana en el Siglo XIX; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Lima, Peru, 1981; p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, M. Tecnología Moderna en los Andes: Minería e Ingeniería en Bolivia en el Siglo XX; Biblioteca Minera Boliviana: La Paz, Bolivia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mitre, A. Bajo un Cielo de Estaño: Fulgor y ocaso del Metal en Bolivia; Asociaciòn Nacional de Mineros Medianos: La Paz, Bolivia, 1993; Volume 6, p. 307. [Google Scholar]

- Peres-Cajías, J.A.; Carreras-Marín, A. The Bolivian Export Sector, 1870–1950. In Latin America’s First Export Era Revisited; Kuntz, S., Ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2017; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Grindle, M.; Domingo, P. Proclaiming Revolution: Bolivia in Comparative Perspective; Institute of Latin American Studies: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2003; Volume 10, p. 424. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, C.D.; Sandoval, A.V.; del Rio, M.A.; Sandoval, F.; Mertens, C.; Parada, C. Santa Cruz: Economía y Poder, 1952–1993; Pieb: La Paz, Bolivia, 2003; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J.A.; Sachs, J.D. Bolivia’s economic crisis. In Developing Country Debt and Economic Performance, Country Studies—Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 157–268. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, J.A.; La Torre, G. Inflación, Estabilización y Crecimiento: La Experiencia Boliviana de 1982–1993; Universidad Catòlica Boliviana, Instituto de Investigaciones Socio-Econòmicas: La Paz, Bolivia, 1995; Volume 1, p. 495. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.J. Guano y crecimiento en el Perú del siglo XIX. In HISLA: Revista Latinoamericana de la Historia Económica y Social; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, W.M. The House of Gibbs and the Peruvian Guano Monopoly; Royal Historical Society: London, UK, 1981; p. 281. [Google Scholar]

- Tantaleàn Arbulù, J. La Gobernabilidad y el Leviatàn Guanero: Desarrollo, Crisis y Guerra con Chile; IEP, Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Jesús María, Peru, 2011; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, J.V. Las Economías de Exportación: Esquema de su Desarrollo en la Perspectiva Histórica; UTEHA: México D.F., México, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, E.; Ocampo, J.A.; Thorp, R. An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Latin America, Volume 1: The Export Age: The Latin American Economies in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries; St. Antony’s Series; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, C. La Economía pùblica en el Perú despuès del Guano y del Salitre: Crisis Fiscal y èlites Econòmicas Durante su Primer Siglo Independiente; Banco Central de Reserva del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2012; p. 478. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, R.; Bertram, G. Peru, 1890–1977: Growth and Policy in an Open Economy; Columbia Essays on Modern Writers, Columbia University Press: New York City, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cotler, J. Clases, Estado y Nación en el Perú; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Jesús María, Peru, 1978; p. 407. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, A.F. The Peruvian Experiment: Continuity and Change under Military Rule; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1975; p. 500. [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan, J. Searching for a Better Society: The Peruvian Economy from 1950; Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 1999; pp. xi, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer-Thomas, V. The Economic History of Latin America since Independence; Cambrige University Press: Cambrige, UK, 2003; p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Miró, M.; Ducoing, C.C. The long run development of Chile and the Natural Resources curse. Linkages, Policy and Growth 1850–1950. In Natural Resources and Economic Growth: Learning from History; Badia-Miró, M., Pinilla, V., Willebald, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Miró, M.; Díaz-Bahamonde, J. The Impact of Nitrates on the Chilean Economy, 1880–1930. In The First Export Era Revisited; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 151–188. [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Miró, M.; Ducoing, C. El PIB industrial de Chile durante el ciclo del salitre, 1880–1930. Rev. Urug. Historia Econ. 2013, III, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Miró, M.; Yáñez, C. Localisation of Industry in Chile, 1895–1967: Mining Cycles and State Policy. Aust. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2015, 55, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, G. Trying to ‘tax and spend’ oneself out of the ‘Dutch Disease’: The Chilean Economy from the War of the Pacific to the Great Depression. In An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Latin America, Volume 1: The Export Age: The Latin American Economies in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries; St. Antony’s Series; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sicotte, R.; Vizcarra, C.; Wandschneider, K. The fiscal impact of the War of the Pacific. Cliometrica 2008, 3, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüders, R.; Wagner, G. Nitrate export collapse and the great depression: Trigger or Chance? Cuad. Econ. 2003, 40, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüders, R.; Wagner, G. Export Tariff, Welfare and Public Finance: Nitrates from 1880 to 1930; Documentos de Trabajo 241; Instituto de Economia, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkel, O. El Presente Como Historia: Dos Siglos de Cambio y Frustración en Chile; Catalonia: Santiago, Chile, 2011; p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Meller, P. Un Siglo de Economía Política Chilena (1890–1990); CEPLAN: Vitacura, Chile, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ffrenc-Davis, R.; Muñoz, Ó.; Benavente, J.M.; Crespi, G. The Industrialization of Chile during Protectionism, 1940-82. In An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Latin America; Cardenas, E., Ocampo, J.A., Thorp, R., Eds.; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 3, Chapter 5; pp. 114–153. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, J.; Lüders, R.; Wagner, G. La República en Cifras, 2010; Technical Report; Universidad Católica: Santiago, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ffrench-Davis, R. Challenges for the Chilean economy under cyclical shocks, 1999–2016. J. Post Keynes. Econ. 2017, 40, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, L. En Modern Svensk Ekonomisk Historia: Tillväxt och Omvandling under två Sekel; SNS förlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, L. Sweden’s Road to Modernity: An Economic History; SNS förlag: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; pp. 1–494. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, L. Sweden—Economic Growth and Structural Change, 1800–2000; Lund Univerdity: Lund, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jonung, L.; Kiander, J.; Vartia, P. The Great Financial Crisis in Finland and Sweden: The Nordic Experience of Financial Liberalization; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- Hodne, F.; Grytten, O.H. Norsk økonomi i det nittende århundre; Fagbokforlaget: Bergen, Norway, 2000; p. 318s. [Google Scholar]

- Bergh, T.; Hanisch, T.; Lange, E.; Pharo, H. Norge fra U-Land Til I-Land: Vekst og Utviklingslinjer 1830–1980; Gyldendal: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerberg, J. Innovation, Path Dependency and Policy: The Norwegian Case; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark, M.; Vikström, P. Growth and structural change in Sweden and a story of convergence Finland, 1870–1990: A story of convergence. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2003, 51, 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fellman, S. Growth and investment: Finnish Capitalism, 1850–2005. In Creating Nordic Capitalism: The Business History of a Competitive Periphery; Iversen, M., Thue, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2008; pp. 139–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hjerppe, R.; Kopi-jyvä. Finland’s Historical National Accounts 1860–1994: Calculation Methods and Statistical Tables; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, J. The Road to Prosperity: An Economic History of Finland; Finnish Literature Society: Helsinki, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, S.; Sater, W.F. A History of Chile, 1808–2002; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; p. 454. [Google Scholar]

- Mamalakis, M.J. Historical Statistics of Chile. Demography and Labour Force; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1980; Volume 2, p. 420. [Google Scholar]

- Grytten, O.H. Why was the great depression not so great in the Nordic countries?: Economic policy and unemployment. J. Eur. Econ. Hist. 2009, 37, 369–403. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Galvarriato, A.; Williamson, J.G. Was It Prices, Productivity or Policy? Latin American Industrialisation after 1870. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 2009, 41, 663–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Scarcity and Frontiers: How Economies Have Developed through Natural Resource Exploitation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.S.; Peres-Cajías, J.A. Bolivian Oil and Natural Gas under State and Private Control, 1910–2010. Boliv. Stud. J. 2014, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugattás, L. Estabilización Macro Económica, Reforma Estructural y Comportamiento Industrial: La Experiencia Peruana; CEPAL: Vitacura, Chile, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, M. Organización Industrial, Características de la Industria y Política Comercial en el Perú: 1971–1985; Documentos de Trabajo, 73; Dpto. de Economía, Pontifica Universidad Católica del Perú: Lima, Perú, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Gomá, Ó. Crecimiento Industrial de Chile: 1914–965; Instituto de Economía y Planificación: Santiago, Chile, 1968; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, J.G. From an Export-led to an Import-Substituting Economy: Chile 1914-39; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2000; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jörberg, L. En översikt över den Svenska Ekonomiska Utvecklingen 1870–1979; Ekonomisk-Historiska Institution: Lund, Sweden, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Edquist, C.; Lundvall, B. Comparing the Danish and Swedish systems of innovation. In National Innovation Systems; Nelson, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 265–298. [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren, H. Welfare capitalism. The Swedish economy 1850–2005. In Creating Nordic Capitalism. The Business History of a Competitive Periphery; Fellman, S., Iversen, M., Sjögren, H., Tue, L., Eds.; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2008; pp. 1850–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lobell, H.; Schön, L.; Krantz, O. Swedish Historical National Accounts, 1800–2000: Principles and Implications of a New Generation. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2008, 56, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönberg, P.O. Learning and Returning: Return Migration of Swedish Engineers from the United States, 1880–1940. Ph.D Thesis, Historical Studies, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, J.; Karonen, P. Business: Rooted in social capital over the centuries. In The Road to Prosperity. An Economic History of Finland; Ojala, J., Eloranta, J., Javala, J., Eds.; Finnish Literature Society: Helsinki, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hodne, F.; Grytten, O.H. Norsk ·okonomi i det tyvende århundre; Fagbokforl: Sentrum, Oslo, Norway, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Norges Officielle Statistikk. Nasjonalregnskap, 1900–1929; Aschehoug: Oslo, Norway, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Stonehill, A. Foreign Ownership in Norwegian Enterprises; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1966; Number 2; pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bruland, K. Norsk mekanisk verkstedindustri og teknologioverføring 1840–1900. In Teknologi i Virksomhet: Verkstedindustri i Norge etter 1840; Lange, E., Ed.; Ad Notam forlag: Oslo, Norway, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist, A.K.; Lindmark, M. Sustainability and Shared Value in the Interwar Swedish Copper Industry. Bus. Hist. Rev. 2016, 90, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranestad, K. Multinational mining companies, employment and knowledge transfer: Chile and Norway from ca. 1870 to 1940. Bus. Hist. 2017, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruland, K. Kunnskapsinstitusjoner og skandinavisk industrialisering—Nasjonalbiblioteket. Demokr. Konserv. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hodne, F. Norges økonomiske Historie 1815–1970; Cappelen: Oslo, Norway, 1981; p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- Cippola, C.M. Literacy and Development in the West; Penguin: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Maliranta, M.; Asplund, R. Training and Hiring Strategies to Improve Firm Performance; ETLA: Helsinki, Finland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Engerman, S.; Mariscal, E.; Sokoloff, K. The evolution of schooling institutions in the Americas, 1800–1925. In Human Capital and Institutions: A Long Run View; David, E., Frank, L., Kenneth, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Go, S.; Lindert, P. The uneven rise of american public schools to 1850. J. Econ. Hist. 2010, 80, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankema, E. The expansion of mass education in twentieth Century latin america: A global comparative perspective. Rev. Historia Econ. J. Iber. Lat. Am. Econ. Hist. 2009, 27, 359–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz, R. Some Observation Concerning the Chilean Educational System and its Relation to Economic Growth. In Education and Economic Development; Anderson, C., Bowman, M., Eds.; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Engerman, S.; Sokoloff, K. The Evolution of Suffrage in the New World: A Preliminary Examination; Hoover Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Engerman, S.L.; Sokoloff, K.L. Economic Development in the Americas since 1500—Endowments and Institutions; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Peres-Cajías, J.A. The Expansion of Public Spending and Mass Education in Bolivia: Did the 1952 Revolution Represent a Permanent Shock? In Has Latin American Inequality Changed Direction? Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, L. The Rise of the Fiscal State in Sweden 1800–1914. In Paying for the Liberal State. The Rise of Public Finance in Nineteenth-Century Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs, H.H. A General Theory of Tax Structure Change during Economic Development; Law Sch. Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, R.; Stern, N.H. Taxation and development. J. Econ. Lit. 1993, 31, 762–830. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, J.L.; Lains, P. Paying For the Liberal State: The Rise of Public Finance in Nineteenth-Century Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 1–310. [Google Scholar]

- Scheve, K.F.; Stasavage, D. Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmo, S. The evolution of policy ideas: Tax policy in the 20 th Century. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2003, 5, 206–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmo, S. Taxation and Democracy: Swedish, British, and American Approaches to Financing the Modern State; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1993; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Lindert, M. Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R.; Zolt, E. Redistribution via taxation: The limited role of the personal income tax in developing countries. UCLA Law Rev. 2005, 52, 1627–1695. [Google Scholar]

- Peres-Cajias, J.A. Public Finances and Natural Resources in Bolivia, 1883–2010. Is there a fiscal curse? In Natural Resources and Economic Growth: Learning from History; Badia-Miró, M., Pinilla, V., Willebald, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aidt, T.S.; Jensen, P.S. The taxman tools up: An event history study of the introduction of the personal income tax. J. Public Econ. 2009, 93, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, K.L.; Zolt, E.M. Inequality and Taxation: Evidence from the Americas on How Inequality May Influence Tax Institutions. Tax Law Rev. 2005, 59, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Roine, J.; Waldenström, D. The evolution of top incomes in an egalitarian society: Sweden, 1903–2004. J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 366–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, P. The Politics of Social Solidarity: Class bases of the European Welfare States; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 353. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, L.W.; Winer, S.L. Tax systems in the world: An empirical investigation into the importance of tax bases, administration costs, scale and political regime. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2006, 13, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riezman, R.; Slemrod, J. Tariffs and collection costs. Rev. World Econ. 1987, 123, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbérg, L.G. The Case of the Impoverished Sophisticate: Human Capital and Swedish Economic Growth before World War I. J. Econ. Hist. 1979, 39, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’Hearn, B.; Baten, J.; Crayen, D. Quantifying quantitative literacy: Age heaping and the history of human capital. J. Econ. Hist. 2009, 69, 783–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleven, H.J.; Kreiner, C.T.; Saez, E. Why Can Modern Governments Tax So Much? An Agency Model of Firms as Fiscal Intermediaries. Economica 2016, 83, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, R. Lessons from Seven Decades of Income Taxation. In Options for Tax Reform; Goode, R., Ed.; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, M.; Ducoing, C.; McLaughlin, E. A Sustainable Century? Genuine Savings in Developing and Developed Countries, 1900–2000. In National Wealth What Is Missing, Why It Matters; Hamilton, K., Hepburn, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark, M.; Acar, S. Sustainability in the making? A historical estimate of Swedish sustainable and unsustainable development 1850–2000. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, K.; Kalimeris, P. Unmasking decoupling: Redefining the Resource Intensity of the Economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619-620, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Meissner, C.M. Market potential and the rise of US productivity leadership. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 96, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitz, M. Catching up, forging ahead, and falling behind. J. Econ. Hist. 1986, 46, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, X.; Maloney, W.F. The Innovation Paradox: Developing-Country Capabilities and the Unrealized Promise of Technological Catch-up; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M. The political economy of the resource curse. World Politics 1999, 51, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonsen, M.; Löfgren, Å.; Nilsson, K.; Westerlund, J. Effects of rent dependency on quality of government. Econ. Gov. 2012, 13, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, P.; Kraus, F.; Pfenning, W. State, Economy, and Society in Western Europe 1815–1975. A Data Handbook in Two Volumes; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grytten, O.H. The Gross Domestic Product for Norway 1830–2003; Norges Bank: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Henrekson, M.; Stenkula, M. Swedish Taxation: Developments since 1862; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–334. [Google Scholar]

- Peres-Cajías, J. Bolivian Public Finances, 1882–2010. The Challenge to make social spending Sustainable. Rev. Hist. Econ. J. Iber. Lat. Am. Econ. Hist. 2014, 51, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portocarrero, S.; Beltrán, B.; Romero, P. Compendio Estadístico del Perú; Universidad del Pacìfico, Centro de Investigacion: Lima, Peru, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| 1850 | 1870 | 1890 | 1913 | 1950 | 1970 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolivia | 640 | 735 | 1006 | 1627 | 1759 | 4805 | |

| Chile | 1011 | 1379 | 2174 | 3617 | 4399 | 6811 | 18,075 |

| Peru | 725 | 933 | 471 | 916 | 2048 | 3439 | 9309 |

| Finland | 1035 | 1238 | 1501 | 2293 | 5208 | 14,416 | 38,074 |

| Norway | 1562 | 2095 | 3040 | 5250 | 7947 | 13,333 | 72,578 |

| Sweden | 1446 | 1807 | 2520 | 4825 | 8816 | 18,133 | 42,043 |

| 1900 | 1913 | 1929 | 1950 | 1970 | 1990 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolivia | 5% | 8% | 16% | 15% | 12% | 11.2 | 17.3% |

| Chile | 18% | 19% | 22% | 12% | 7% | 8% | 11% |

| Perú | 7% | 11% | 18% | 12% | 12% | 13% | |

| Norway | 1% | 12.5% | 19% | ||||

| Sweden | 7% | 9% | 5% | 8% | 9% | 5% |

| Bolivia | Chile | Peru | Norway | Sweden | Finland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1850–1870 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.2 | |

| 1870–1890 | 3.8 | –3.6 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.1 | |

| 1890–1913 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| 1913–1919 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | –0.5 |

| 1919–1929 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 5.7 |

| 1929–1939 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| 1939–1950 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| 1950–1973 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| 1973–1990 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| 1990–2003 | 3.4 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| 2003–2010 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 6.1 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 3.4 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ducoing, C.; Peres-Cajías, J.; Badia-Miró, M.; Bergquist, A.-K.; Contreras, C.; Ranestad, K.; Torregrosa, S. Natural Resources Curse in the Long Run? Bolivia, Chile and Peru in the Nordic Countries’ Mirror. Sustainability 2018, 10, 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040965

Ducoing C, Peres-Cajías J, Badia-Miró M, Bergquist A-K, Contreras C, Ranestad K, Torregrosa S. Natural Resources Curse in the Long Run? Bolivia, Chile and Peru in the Nordic Countries’ Mirror. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040965

Chicago/Turabian StyleDucoing, Cristián, José Peres-Cajías, Marc Badia-Miró, Ann-Kristin Bergquist, Carlos Contreras, Kristin Ranestad, and Sara Torregrosa. 2018. "Natural Resources Curse in the Long Run? Bolivia, Chile and Peru in the Nordic Countries’ Mirror" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040965

APA StyleDucoing, C., Peres-Cajías, J., Badia-Miró, M., Bergquist, A.-K., Contreras, C., Ranestad, K., & Torregrosa, S. (2018). Natural Resources Curse in the Long Run? Bolivia, Chile and Peru in the Nordic Countries’ Mirror. Sustainability, 10(4), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040965