1. Introduction

There is great need for multidimensional frameworks to guide diverse stakeholders from government, business, and civil society as they attempt to collaboratively solve complex societal problems [

1], such as poverty and developing sustainable food systems [

2]. Nonlinear, dynamic, and involving interactions between various structures and stakeholders, these problems require collaborative approaches that need to be sustained over long periods [

3]. For addressing such so-called “grand challenges” [

4,

5,

6] or “wicked problems” [

7,

8,

9], the collective impact framework that has been developed in the fields of philanthropy and social innovation has been widely touted since 2011. Collective impact partnerships (CIPs, as we call them in this paper) involve “long-term commitments by a group of important actors from different sectors to a

common agenda for solving a specific social problem. Their actions are supported by a

shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, and

ongoing communication, and are staffed by an independent

backbone organization” (emphasis added) [

10]. A body of literature on collective impact has emerged in a context where researchers are also deepening understanding about inter-organizational collaborations more broadly, including motivations for engaging in them [

11,

12], the various types of partnerships [

13], their stages of evolution and value creation [

14,

15], strategy formulation and implementation processes [

16], and assessment of their impacts [

17]. Among various types of inter-organizational collaborations involving foundations—such as “affinity groups” and “learning partnerships” [

18,

19,

20,

21]—collective impact continues to gain widespread use in multiple domains, as it is “appealing in its simplicity” [

22], and provides one of “the clearest frameworks” to guide decision-makers’ collaborative work [

2,

23]. Additionally, the framework emphasizes impact, which governments, community organizations, and funders particularly are concerned about [

18].

While acknowledging the utility of the collective impact framework, critics have noted the need for further developing its theoretical foundation beyond its underlying upper management, top-down approach, and for its practical implementation based on empirical evidence beyond the business sector [

2]. Some argue that it does not adequately draw upon the prior extensive research on inter-organizational collaboration and community-engaged research, and the issues of equity and power that such literature highlights [

22]. Additionally, little attention has been paid to empirically-informed theory about the processes by which partnerships for collective impact are initiated and evolve [

24]. Further, there is limited guidance about how to implement various elements of the approach when stakeholders span civil society, government, and business [

25]. Efforts are being made to incorporate perspectives from community-engaged research and practice to strengthen the theoretical foundations of collective impact [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Others have also addressed questions about the implementation of different aspects for collective impact, such as the functions of backbone organizations [

31]. Recently scholars have proposed an updated collective impact framework, expanding it from a management to a “movement building” paradigm [

32]. This paper draws from the original and updated frameworks, summarized in

Table 1.

Despite developments noted above, limitations remain in the collective impact framework. Critics and proponents alike widely acknowledge that seemingly intangible factors, such as interdependent human interactions and relational dynamics are at the heart of a complex system’s ability to adapt and evolve for collective impact [

33]. Yet, while the collective impact literature has embraced emergence and acknowledged the non-linearity of processes and outcomes [

34], work remains to be done in theorizing and measuring complex stakeholder interactions for emergence. Inter-organizational collaboration researchers point out that monumental challenges remain in measuring seemingly intangible factors during collective impact processes, to inform stakeholders about progress and changes needed for sustainable solutions to complex societal problems [

35,

36]. Questions persist about measurements to demonstrate how relationships formed between individual stakeholders in various types of partnerships spanning organizations and institutional sectors (business and government, in addition to community) may contribute to the emergence of CIPs [

33,

34,

37], and outcomes that evolve as stakeholders learn [

36,

38,

39]. The challenges of measuring seemingly intangible, nonlinear changes and showing results of collaboration efforts in CIPs have practical implications. Faced with measurement-related challenges, some stakeholders may become disenchanted about CIPs or other collaborative processes over time, sometimes reverting to the norm of working in silos [

35], rather than sustaining engagement with other stakeholders. Such disengagement has been noted among well-resourced organizations that may be unwilling to cede their agendas to the desires of knowledgeable, yet resource-poor communities, who, in turn, may feel dominated or ignored by funders [

22,

25].

This paper’s purpose is to contribute to theory and practice in addressing critiques of the collective impact literature, and specifically in measuring individual stakeholders’ interactions and how emergence occurs. We grapple with the question:

How can decision-makers coherently conceptualize and measure seemingly intangible factors to sustain partnerships for the emergence of collective impact? We carried out a case study to address this question between 2013 and 2017. The period encompassed the latter part of a decades-long partnership in the province of Quebec, involving Canada’s largest private family foundation, the Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation (with initial assets of 1.4 billion Canadian dollars); the Quebec government; multiple community organizations; and a few businesses promoting healthy lifestyles [

40,

41]. A “collective impact project” emerged over the period [

42]. To develop our case study, data collected and analyzed included documents, interviews with 24 philanthropy leaders in Quebec and beyond, concerning their experiences innovating in partnerships between foundations and other types of organizations to solve complex societal problems, as well as interviews and observations of multiple stakeholders participating in the Quebec processes that we focused on.

Our data highlighted foundations’ role in “convening” and “facilitating” interactions among diverse individuals from multiple organizations and institutional sectors over time, for learning and collaboratively crafting strategies and innovating for solving complex societal problems through partnership structures such as CIPs. Highlighting the importance of individual-level interactions across institutional sectors, Tim Brodhead, who worked extensively in international development and served as President and CEO of The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation from 1995–2011, noted [

43]:

Governments and business have created international institutions that allow them to communicate and collaborate, but our ability to connect as individuals lags far behind […] Business and governments, rightly or wrongly, are distrusted, their motives are suspect. We must open other channels that allow for direct person-to-person links—exchanges, collaborative projects...

Thus, we explored the processes through which individuals embedded in various organizations across institutional sectors convened to interact over time for collective impact. The

multidimensional proximity framework [

44,

45,

46,

47] provided a useful analytical lens for the Quebec case. While acknowledging calls for application of theories and frameworks such as the Community Coalition Action Theory (CCTA) [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52] and the “Above and Below the Line” (ABLe) Change Framework (“Above” representing conceptualization, “Below” for implementation) [

53], to address the limitations of collective impact research noted above, we used the proximity framework, as it has been used in prior research with stakeholders spanning institutional sectors, including community organizations and businesses. Largely developed by economic geography scholars [

45,

46,

54], the proximity framework has been useful in explaining inter-organizational collaboration for innovation to solve problems [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60], particularly in technological domains [

61]. The basic premise is that proximity reduces uncertainty and solves coordination problems [

46,

62]. It fosters coordination and trust, thereby facilitating interactive learning and innovation. For example, it is relatively easier for geographically proximate actors to communicate and share knowledge that contributes to innovation [

61]. Thus, our use of the framework provides opportunity for better integrating collective impact research and practice into the broader academic discourse and development of practical tools for cross-sector collaboration and learning to solve complex societal problems. Additionally, the proximity framework allows us to explicitly theorize about individual stakeholders’ interactions at various stages of collaboration processes, and potential associations with outcomes, addressing another limitation of prior accounts, in which the role of individual human interactions for collective impact has remained implicit.

Whereas the initial literature on how proximity drives learning and innovation in inter-organizational collaboration largely focused on

geographical proximity [

63], other dimensions—including

organizational, institutional (or cultural), cognitive, and social proximity—have been specified over the past two decades [

44,

46]. Empirical studies show that each dimension’s role depends on the type of knowledge being produced [

47], characteristics of collaborating organizations, and type and phase of partnerships [

60]. For example, factors explaining why technological firms located close to universities and research labs had a greater likelihood of collaboration and major innovation were beyond, although related to geographical proximity. Entrepreneurs who had previously worked at universities and research labs, and had continued to live in the same area had maintained personal relationships with people in the institutions, with continued interactions that enhanced learning and innovation [

55]. This represents social proximity, which has been found to be linked to greater innovative performance at the firm level [

64], but has not been theoretically developed in the CIP literature despite the emphasis on building trust and relationships for collective impact [

10,

32,

33,

35]. Social proximity measures such as an ego’s trust, willingness to share information and put effort into requests by the alter have been shown to impact collaboration and innovation [

61]. Drawing on cases from technological domains, proximity researchers note that where learning and innovation need to occur among individuals whose norms and values differ, such as those from different institutional sectors or regions (e.g., decision-makers from government or business and a community organization), enabling social proximity may be especially vital. One of the advantages of the proximity framework is that, rather than privileging factors, such as the social capital of some groups (e.g., resource-rich business leaders), it highlights the distances between any two stakeholders at the beginning of collaboration processes (e.g., distance between business and community decision-makers’ social networks, differences in their understanding of a problem), and how they evolve over time. Further, the relationships between different dimensions of proximity, processes, and outcomes are not linear, allowing for capturing complexity in interactions during collaborations. For example, two stakeholders who are too cognitively proximate may not be able to learn much that is new from each other, while being too distant, also impedes learning [

43]. This implies that iterations between divergence and convergence may be needed to arrive at optimal levels of proximity for learning while collaborating for collective impact [

61]. Given the multiple dimensions and definitions of proximity [

58], it is imperative to specify the meanings we use in this paper, drawing from prior research (

Table 2).

Findings about proximity in technological domains have potential applications in other spheres, such as in collaboration for solving complex societal problems. From the Quebec case that we analyze, we show how various dimensions of proximity are associated with iterative processes of divergence and convergence to address the complex challenge of preventing obesity and weight-related problems, for the emergence of a CIP. Beyond prior research that highlights proximity as enabling collaboration for technological innovation (i.e., proximity as cause, innovation as consequence), we develop a multidimensional proximity model to show how various dimensions of proximity were iteratively enabled among individual decision-makers interacting within and across organizations and institutional sectors in Quebec, while enabling the emergence of collective impact (i.e., proximity as iterative cause and effect of strategies and partnership structures for collective impact). We situate ours among

process studies [

74], which are more concerned with “a series of occurrences of events rather than a set of relations among variables” [

75], and do not attempt to locate “singular causes” for outcomes [

76].

The rest of our paper is divided into 4 sections. First, we summarize our processual analysis, which involved iteratively analyzing theory and the data [

74], in an inductive approach. Second, we elaborate on our integration of the disparate bodies of literature on collective impact and proximity, and our extension of the multidimensional proximity framework from the domain of technological innovation in applying it to the Quebec case. We show how emergence of collective impact involves iterations of divergence and convergence, as various dimensions of proximity are enabled among stakeholders. A third section discusses the implications of our findings, as we propose future proximity research that addresses the limitations of this study, while informing managers and researchers of ongoing CIPs in Quebec and beyond [

42,

77]. We then conclude by highlighting our paper’s contributions to theory and practice of collective impact, as well as to the literature on proximity.

2. Materials and Methods

The research informing this paper was initiated to inform a foundation and a university research center that had the goal of developing a framework for how philanthropy simultaneously engages government, business, and community organizations in innovating to solve complex societal problems [

41,

78]. As the processes of collaboration that we studied had already begun, the relevant actions of stakeholders could not be manipulated. Thus, an inductive approach was used in collecting data from multiple sources for case study development [

79,

80]. Prior to data collection, ethical clearance was obtained from the ethics board of the authors’ institution (June 2013), and written informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

The study proceeded in two phases. First, to understand the context within which foundations engage in cross-sector partnerships, we reviewed literature, including academic publications, organization strategy documents, program and project reports, and websites of philanthropies and cross-sector initiatives; followed by interviews of a purposive sample of 24 philanthropy leaders with extensive experiences in multi-stakeholder partnerships at global, national, provincial, and community levels.

Table 3 summarizes information on the philanthropy leaders who we interviewed over the period from July to December 2013. Semi-structured interviews lasted from 45 to 90 min. Our interview questions were about decision-makers’ partnership processes, including (i) collectively defining problems, (ii) overcoming organizational and institutional barriers and identifying synergies; and (iii) developing activities and metrics for innovations to realize shared goals.

Findings from the three themes addressed by philanthropy leaders then guided our study protocols for the in-depth Quebec case study. Our objective was to analyze historical and real-time philanthropy-supported partnership processes involving diverse individual stakeholders who interacted with each other and with the organizational structures in which they were embedded, across multiple institutional sectors. Thus, we adopted a process approach in iteratively collecting and analyzing multiple types of data [

74]. We reviewed documents and notes from interviews and participant-observations of meetings at the provincial, regional (Montreal), and local levels from September 2013 to March 2017, in evaluating the partnership processes and evolution of networks supported by Québec en Forme (QeF), the focal NGO that implemented Quebec’s government-philanthropy partnership to address obesity and weight-related problems (

Table 4). The networks included organizations spanning public (e.g., municipal government), community (e.g., early childhood centers, schools and school boards, clinics and health centers, community development centers and neighborhood associations) and, to a smaller extent, business (e.g., local enterprises, including in agri-food, etc.).

We focused on two community networks that were partly supported by QeF—Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (NDG) and Centre-Sud in the Montreal region. We selected the two because their processes were deemed by QeF to exemplify the complexity of their multi-stakeholder processes, and the community actors granted access for our research to be conducted. In each community network, representatives from diverse organizations convened regularly over years, in fortnightly or monthly meetings, to develop and implement anti-poverty strategies. The meetings were part of multi-stage iterative processes by which the multiple organizations in each community network were mobilized, partly with QeF funding and technical assistance provided by QeF coordinators designated to each community. The processes included developing profiles of their communities to assess their needs related to healthy eating and physical activity; using the community profiles to inform a diagnostic analysis of the priorities to be tackled in the community; developing a shared vision of change; crafting a three-year strategic plan; specifying annual action plans with interventions that they collectively proposed; applying for funding from QeF and other funders to leverage community resources for interventions that the community network member organizations implemented; and evaluating their strategic plans and the associated action plans and interventions.

We iterated between data collection and analysis, incorporating emerging themes into follow-up reviews, interviews, and focus group discussions, and what we focused on during observations. Differing from analyses based on variance, our processual analysis was more concerned with “a series of occurrences of events rather than a set of relations among variables” [

75], we were not attempting to locate “singular causes” for outcomes [

76], and we did not seek to generalize findings. Rather, we were guided by five assumptions underlying processual analysis [

74]. First, the processes of the sampled communities were also embedded at multiple levels, so we paid attention to events at the regional (Montreal), provincial (Quebec), federal (Canada), and global levels. Second, there were interactions between the diverse stakeholders who interacted with each other and with structures in which they were embedded at the multiple levels noted. Third, the processes that we analyzed were temporally connected, in that events prior to our data collection, those ongoing during our data collection in 2013–2017, and events of the future are related to each other. Fourth, the structures, events that occurred, and decision-makers’ roles emerged over time, in a complex manner that linear and unidimensional explanations are unable to account for. Finally, processes at the level of the sampled communities are linked to outcomes at multiple levels in multiple domains. For example, some individual stakeholders who were operating in organizations at the regional level at the start of our data collection transitioned to work at community-level organizations, while others moved from provincial to regional level organizations, and vice-versa. In unanticipated ways, some stakeholders also became involved in the collective impact project that emerged at the latter part of this study. We triangulated between the different types of data collected, determining key themes from coding and analyzing notes. For example, after initial interview questions about the types of problems that stakeholders focus on in their community networks and observations of discussions at meetings, we refined data collection protocols to gather richer data on the differences in stakeholders’ priorities based on their understanding of specific problems that were noted in meetings, such as food security or physical activity.

We had multiple stages of coding and analysis [

81,

82]. Beginning with open coding, we summarized the data collected with a code that was often verbatim from the informants, linked with text from interviews/notes. This was followed by axial coding of the categories from the open codes, involving moving to developing descriptive categories of researcher-centric concepts about actors, structures, processes, and outcomes; and then theoretical coding, with identification of themes to describe and explain what was emerging from the data. Although we were not seeking to generalize findings, and did not have access to data to formally compare the processes we observed in the two communities sampled with others, we validated our analyses of the data through focus group discussions and interviews with key decision-makers who work with multiple community networks in Montreal.

Two sets of key themes emerged from our data. The first set of themes was about the challenges/opportunities among stakeholders during collaboration processes, categorized as geographical, organizational, cognitive, social, and institutional factors. A second set of themes was related to the timeframes and measures of collaboration processes among stakeholders. This second set of themes resulted in our analyses of the first set of themes through the lens of short-, medium-, and long-term frames. Given the sets of themes highlighted in our data, we used the proximity framework to analyze how multiple dimensions of proximity are associated with collaboration processes and measures of progress in the short-, medium-, and long-term, as diverse stakeholders interact for the emergence of collective impact partnerships to solve complex societal problems. For example, initial text about meetings highlighted the convening of stakeholders, and in turn the enabling of geographical proximity in the short-term, or organizational proximity in the medium-term.

3. Results

A short case of foundation-supported partnerships provides a prelude to the multidimensional proximity framework and its utility for analyzing the Quebec case. In what has become one of the best known examples of collective innovation efforts to address complex societal problems, the history of the Green Revolution illustrates how geographical proximity between key decision-makers from two foundations iteratively enabled other dimensions of proximity, for the emergence of strategies and partnership structures to address food insecurity at a global level (

Box 1).

Box 1. Proximity and the emergence of partnerships for the Green Revolution

According to historical accounts [

83], in the 1950s Forrest “Frosty” Hill, Vice President for Overseas Development of the Ford Foundation, and J. George Harrar, Deputy Director for Agriculture at the Rockefeller Foundation habitually rode the same commuter train from Scarsdale, where they both lived, into New York City, where their offices were a few blocks from each other (

geographical proximity). Due to their geographical proximity, the two began to engage in informal conversations during their commute and developed a friendship (

social proximity). Their conversations also deepened their shared understanding about challenges faced in agriculture in developing regions (

cognitive proximity), leading to formal collaboration between the two foundations (

organizational proximity): they collectively supported research centers to engage in agricultural innovations for growing sturdier, more productive crops. Subsequently, the collaborations between the two foundations and the research centers they supported extended across institutional sectors, including the United Nations, the World Bank, agri-business, and other academic institutions (

institutional proximity), and was formalized in the formation of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), which comprised the research centers. These efforts contributed to the prioritization of agriculture on the international development agenda in the 1960s and 1970s, becoming known as the Green Revolution. The extensive global network and movement that emerged from the geographical proximity of two decision-makers iteratively enabled other dimensions of proximity and the partnership structures that emerged, and contributed to a greater degree of food security for developing nations, staving off projected famines, especially in Southeast Asia.

The historical case of the Green Revolution, with its complexities in outcomes, points to the utility of the multidimensional proximity framework, in explaining how partnership structures, such as the CGIAR emerged, partly from the interactions of two individual decision-makers. The case is also consistent with other empirical studies showing how geographical proximity stimulates social proximity, as reduced geographic distances favor social interaction and the building of trust for knowledge transfer [

46,

84], and social entrepreneurship [

85].

In this paper, we focused on

Collective Impact Partnerships (CIPs), as our data from philanthropy leaders and the Quebec case specifically highlighted CIPs for collectively addressing complex societal problems. Enabling interactions between individual stakeholders, which we conceptualize as enabling various dimensions of proximity [

46], is the key mechanism for the emergence of collective impact in the case we studied in Quebec. Building on decades-long efforts and province-wide mobilization particularly in the early 2000s, the case that we studied involved engaging key actors from across sectors around solving a specific societal issue: unhealthy lifestyles and weight-related problems [

40,

86].

Our data showed that the five conditions that Kania and Kramer (2011) and Cabaj and Weaver (2016) proposed for CIPs (

Table 2)—which we relate to the proximity dimensions in this section—were manifested to different extents in three timeframes that we identified in the emergence of the CIP in Quebec. We organize our study findings according to the three timeframes, which also guide our development of a model showing how various dimensions of proximity were associated with divergence and convergence that characterized the partnership processes. First, in the short-term was the role of philanthropy and key partners such as the provincial government in

convening diverse stakeholders around shared aspirations to collaborate in developing and implementing strategies to address complex societal problems. In the model that we develop, we conceptualize the convening of stakeholders around shared aspirations or a common agenda, one of the CIP success conditions, as enabling the geographical dimension of proximity.

Second, in the medium-term was developing formal partnerships networks, which added in the four remaining CIP conditions: having a backbone organization, engaging in continuous communication, mutually reinforcing activities, and a shared measurement system. This second timeframe is conceptualized in our model as making efforts to further develop geographical proximity, and in turn enable organizational, cognitive, social, and institutional proximity.

Third, during what we specify as the long-term timeframe, we highlight the challenge in realizing one of the CIP conditions that we specify: developing shared measures of qualitative processes and outcomes, for sustaining learning and engagement of stakeholders. We found that the lack of baseline measurement of largely qualitative factors—conceptualized as cognitive, social, and institutional proximity between stakeholders, which some evaluations suggested were important for explaining which community networks successfully brought about desired outcomes—is a problem in providing evidence for sustained engagement of stakeholders, such as government and local businesses. We show the emergence of a CIP in Montreal, Quebec in this timeframe, and note the need for frameworks to conceptualize and measure qualitative factors during the CIP’s processes. We use the case to develop a multidimensional proximity model that coherently conceptualizes qualitative proximity factors, for measuring their change over time.

3.1. Convening of Diverse Stakeholders around Shared Aspirations in the Short-Term: Quebec, 2001–2006

A first condition for successful CIPs is for stakeholders to have

shared aspirations [

32], or a

common agenda [

10], elaborated as “a shared vision for change, one that includes a common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving it through agreed upon actions”. Shared aspirations or a common agenda are less likely to form when stakeholders from different institutional sectors are working in silos. Recognizing that multiple individuals may be implicated in any such effort, for simplicity, we use examples of dyads. For example, in the case of Quebec in the 1980s, decision-makers from government (Stakeholder #1) made efforts to prevent obesity through banning fast-food advertisements to children [

87]. The problem was viewed as one that could be solved by regulation. However, such a strategy occurred in parallel with a strategy by business leaders (Stakeholder #2), including those from outside Quebec, of marketing fast-food to youth, rather than being concerned with addressing obesity. As these two stakeholders formulated and implemented their deliberate strategies in silos, there was no convergence in aspirations or outcomes. Businesses spent resources producing and marketing fast-food, leading to weight-related health problems in society, whereas public resources were spent to treat such problems.

Informants emphasized the importance of addressing siloed approaches to solving complex problems by convening and engaging all relevant stakeholders to deepen their understanding of the specific contexts, spaces, or places where problems are being addressed, especially during iterative processes of co-creating strategies. Stephen Huddart, President and CEO of the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation notes [

88]:

There is a recognition that we [foundations] are part of the system that we are trying to change. So we realize that in changing ourselves, we change the relationships to the systems and the people in the systems that we are working with [...] It is when you have various actors bringing their multiple perspectives to a problem that we are able to address them in a holistic and more long-lasting way.

Public health processes in the 1990s and 2000s in Quebec were illustrative of approaches that convene stakeholders and break down silos. Over decades, there were multiple forums for dialogue around obesity prevention [

89,

90,

91], representing efforts at enabling proximity between stakeholders for strategy formulation. For example, in 2000, an association of public health professionals convened a group of experts from multiple sectors and created a committee—the Groupe de travail provincial sur la problématique du poids (GTPPP)—with two key objectives: to develop a common understanding of the obesity problem, and to develop a global and multi-sectoral plan to address the problem [

92]. Findings from the GTPPP and various other local, provincial, federal, and global taskforces and committees, including the WHO [

93], subsequently informed the development of a number of policies, including a Public Health Act (PHA) in 2001 that was to guide geographically-defined regions and communities [

94]. In our model, efforts at convening diverse individual stakeholders represents enabling

geographical proximity (denoted by the solid

GP arrows in

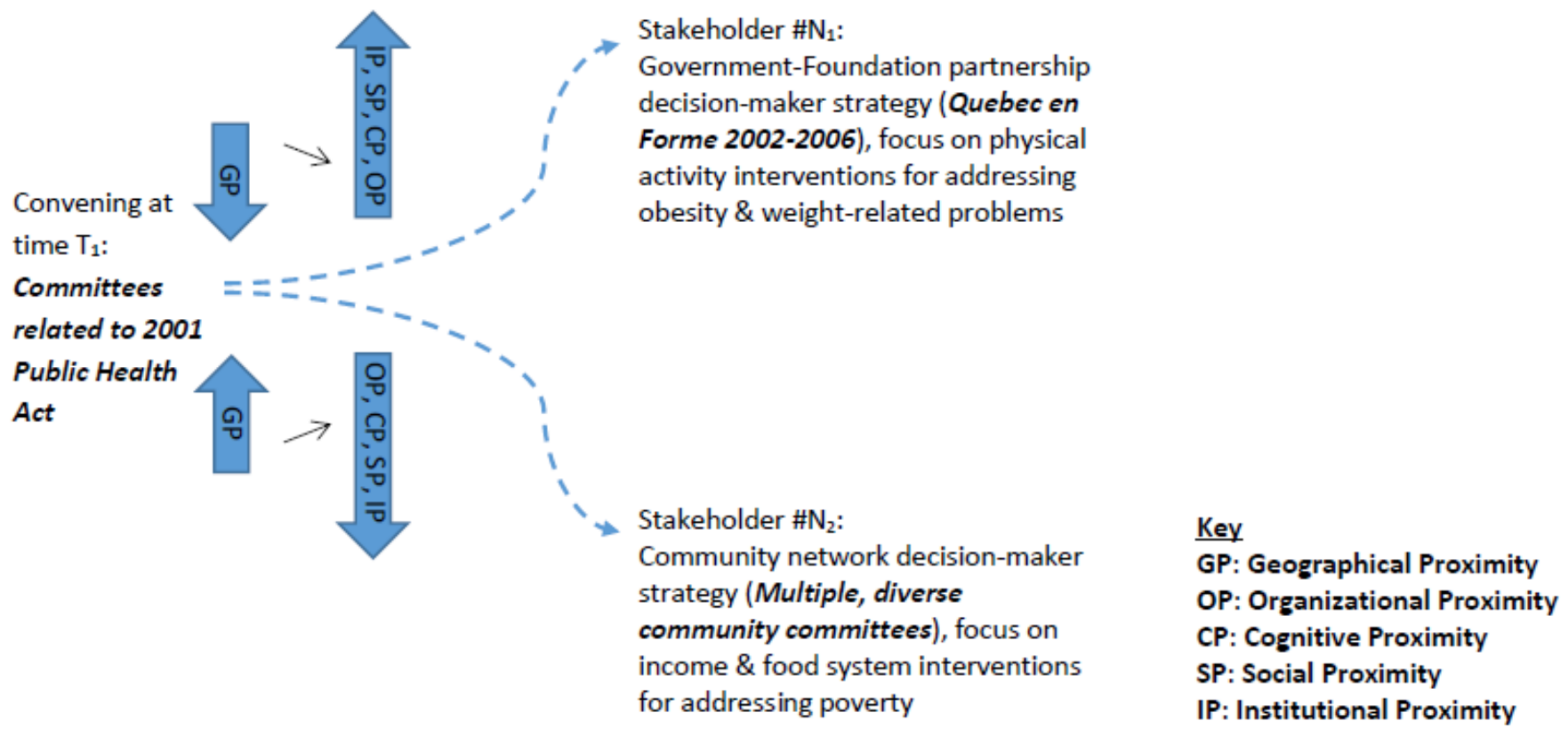

Figure 1).

Despite convening efforts, this phase of the Quebec case in the early-2000s was characterized by

divergence in strategies, as the perspectives of stakeholders from some institutional sectors were missing in forums that were convened to develop strategies and partnerships. From our findings in the first phase of the Quebec case, we built the first part of our model, illustrated in

Figure 1. We found that despite a desire to engage diverse actors with expertise on the multiple issues related to addressing the “weight problem,” during deliberations to build on the 2001 PHA in the early 2000s, there was relatively greater engagement by physical education experts, who saw physical activity as the solution to the obesity problem, and resulting strategies were relatively skewed towards physical activity, as compared to nutrition and food security. Indeed, following an agreement between the Quebec government and the Chagnon Foundation a partnership strategy was adopted to promote physical activity (denoted by Stakeholder #N

1 in

Figure 1), due to the understanding of the obesity problem. The Chagnon Foundation and government created an NGO, Quebec en Forme in 2002, “to promote physical fitness among disadvantaged children aged 4 to 12 years” [

95]. QeF had emerged from a pilot project in one of the 17 administrative regions of Quebec (Mauricie-Trois-Rivières), as the Chagnon Foundation sought to address the needs of youth from families with low-income. Given evidence that decision-makers had seen of low-income youth being motivated to stay in school through participation in sports [

96], an underlying assumption for QeF’s initial work was that getting lower-income youth in sports would contribute to addressing problems of poverty and inequality that concerned them, including obesity [

97].

Enabling geographical proximity in the short term was not enough for collective impact, though. Collective efforts were initially counteracted by cognitive, social, organizational, and institutional distances between stakeholders.

Table 5 summarizes our findings that despite enabling geographical proximity, there were other dimensions of distance between stakeholders.

These dimensions are denoted by the solid “OP,CP,SP,IP” arrows in

Figure 1 depicting negative

organizational proximity (

OP),

cognitive proximity (CP),

social proximity (SP), and

institutional proximity (

IP), which tended towards divergence. The strategy of decision-makers in the government-foundation partnership (Stakeholder #N

1, with focus on physical activity) diverged from the strategy of other stakeholders (e.g., Stakeholder #N

2, with focus on food security by some community organizations) in

Figure 1.

Despite such divergence, geographical proximity may, in turn, enable other dimensions of proximity (denoted by the little arrows from

GP towards the other dimensions). The order in which different dimensions of proximity are enabled depends on the context [

60]. For example, in the case of the Green Revolution (

Box 1), geographical proximity enabled social and cognitive proximity, which further enabled organizational and institutional proximity, in turn. In the Quebec case, other proximity dimensions were enabled in a second phase of partnership processes.

3.2. Development of Formal Partnerships Networks in the Medium-Term: Quebec, 2007–2017

A second set of CIP conditions are largely organizational. This set includes having a

backbone support organization with dedicated staff, “separate from the participating organizations who can plan, manage, and support the initiative through ongoing facilitation, technology and communications support, data collection and reporting, and handling the myriad logistical and administrative details needed for the initiative to function smoothly” [

10].

Continuous communication is another condition that is directly related to geographical, organizational, cognitive, and social factors. Geographical proximity has motivated, and typically characterizes an organization, as it facilitates face-to-face interactions. Establishing formal partnerships between organizations—enabling organizational proximity—facilitates more regular face-to-face interactions among decision-makers from different organizations, possibly enabling other dimensions of proximity. That geographical and organizational proximity enable cognitive proximity is implied in CIPs, in the need for stakeholders to share their “deep knowledge” with each other in CIPs [

10]. Social proximity is also implied in CIPs, with the recognition that “developing trust among nonprofits, corporations, and government agencies is a monumental challenge,” so that CIP participants “need several years of regular meetings to build up enough experience with each other to recognize and appreciate the common motivation behind their different efforts [

10]”. Engaging in

mutually reinforcing activities is another condition. Whereas not all organizations in CIPs are expected to do the same thing, each is expected to undertake a “specific set of activities at which it excels in a way that supports and is coordinated with the actions of others”.

Beyond short-term convening that our model conceptualizes as enabling geographical proximity, philanthropy leaders in our study emphasized the longer-term processes by which formal organizational partnerships—which we conceptualize as organizational proximity—that characterize CIPs for solving problems were emerging. Notes Hilary Pearson, President and CEO of Philanthropic Foundations Canada (PFC), an association of Canadian foundations, charities, and corporations [

98]:

There is a significant interest [in philanthropies and other types of organizations] about collaboration ... in a way that there was not, five or six years ago. So we’re seeing more structured groups coming together ... A lot of it is really just about exchanging ... learning ... talking to each other about projects ... there isn’t really as much formal pooling of money. [Organizations] tend to be more reluctant about getting into pooled fund projects partly because of processes ... because of governance issues, because of accountability issues, because of communication issues they might perceive ... You don’t see as much formal collaboration as you would think, but it’s coming.

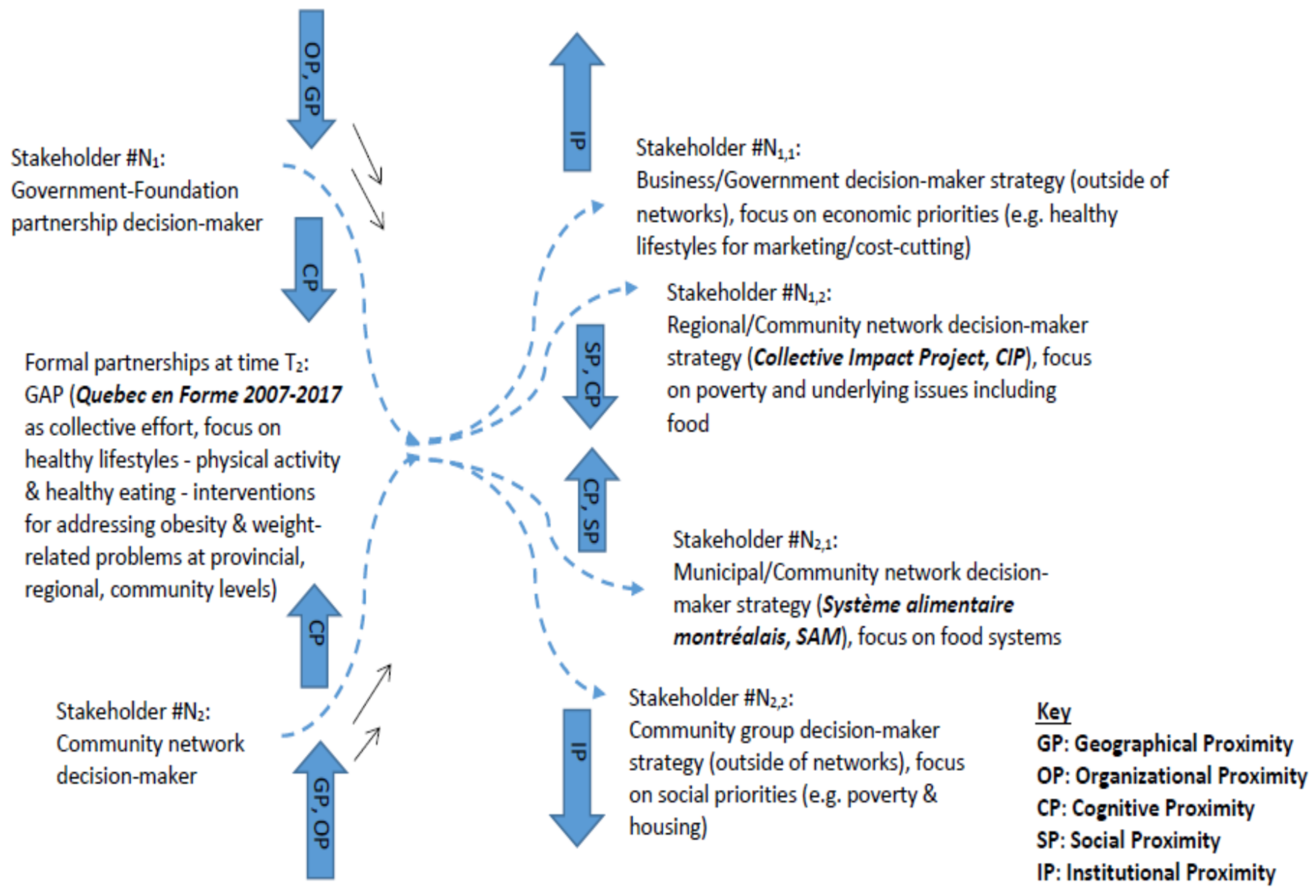

We observed the slower evolution of such formal partnerships in our empirical study in Quebec in a second phase from the mid-2000s to mid-2010s, during which there were iterations between convergence and divergence of stakeholders’ strategies and organizational structures. Quebec’s 2001 Public Health Act (PHA), which had been crafted in the previous phase (

Figure 1), provided the context, and was the starting point for various processes that took place in this second phase. As noted before, in the previous period, there was divergence between stakeholders, such as QeF (Stakeholder #1, representing the government-Chagnon Foundation partnership) and community groups (Stakeholder #2) in

Figure 2.

In this second phase, co-location/meetings and developing participation in organizational networks supported by QeF represented enabling

geographical proximity (

GP) and

organizational proximity (

OP), respectively, between these two sets of stakeholders, denoted by the solid arrows “GP,OP” tending towards convergence in

Figure 2. Particularly, following the 2001 PHA, there were additional forums for face-to-face deliberations among diverse stakeholders in multiple committees, leading to Quebec’s 2006

Government Action Plan (GAP) to promote healthy lifestyles and prevent weight-related problems. At the organizational level, to implement the GAP, the government-Chagnon Foundation partnership pooled resources to create a Fund for Healthy Habits, committing to investing 480 million Canadian dollars over the period 2007–2017, with a focus on the underprivileged population aged 0 to 17 years across Quebec. Initially, a management corporation

(Société de gestion du Fonds pour la promotion des saines habitudes de vie, SGF) managed 25% of the pooled funds for major provincial and regional projects, while 75% of the funds designated to support mobilization, development and implementation of strategies by local community networks were managed by QeF, the nonprofit that had been established by the Chagnon Foundation in 2002 [

86].

Geographical and organizational proximity also enabled

cognitive and

social proximity between individuals from across sectors (denoted by the little arrows from the solid “

GP,

OP” arrows towards “

CP,

SP”) during iterations between convergence and divergence of strategies among stakeholders. Iterations of interactions between decision-makers during agenda-building and review sessions that had started in the previous phase also directly informed changes in their understanding about the “problem”. This is denoted by the solid “

CP” arrows on the left hand side, depicting cognitive proximity in

Figure 2, also attracting stakeholders towards convergence. In addition to initially prioritizing physical activity to address the problem, food and healthy diets also came to be included by stakeholders as a priority for the GAP, due to the input by nutrition experts. Given QeF’s role in implementing the GAP, in 2006 it expanded its organizational mandate from its initial focus on physical activity for the population aged 4–12, to also include “healthy eating” among the population aged 0–17 years [

86]. This exemplifies QeF aligning its organizational mandate to become proximate with nutrition experts and community organizations involved in the GAP. The adoption of the GAP by physical activity and healthy eating advocates to promote “healthy lifestyles” represented the emergence of a

common agenda, which is one of the characteristics of a CIP [

10], although the collective impact framework had not yet been developed, and it was not explicitly framed as such in the Quebec case.

Organizational partnership structures were further consolidated during this period. An initial review of the GAP highlighted the need for improving coordination with geographically-defined local level stakeholders for strategy elaboration and implementation [

40]. Thus, “to ensure greater consistency among strategies and create a synergy among all funded projects, the Quebec government and Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation decided to bring [SGF and QeF] closer together,” with a 2010 merger consolidating QeF as the

backbone organization for engaging with all stakeholders [

95]. QeF interacted with networks of organizations across public, private, and civil society sectors engaging in

mutually reinforcing activities characteristic of CIPs—although not explicitly specified as such in this case—and undertaking specific activities to promote healthy eating and physical activity in their respective communities [

95]. Thus, for example, QeF set up regional offices that became hubs from which QeF funded, and directly provided technical assistance to geographically-defined

local partner groups (

LPGs, or Regroupements locaux de partenaires, RLPs), networks of organizations spanning public, community and, to a smaller extent, business sectors. The LPGs were to identify problems, and develop and implement strategic plans to advance the healthy lifestyles agenda [

95]. In each region, “development agents” were mandated to reach out and coordinate with the LPGs. Having started with 35 geographically-defined LPGs in eight administrative regions in 2007, by 2013 QeF was working with 157 LPGs across the 17 regions of the province, including existing local organizational networks, and others created by assembling local stakeholder organizations in partnership for the first time (

Table 6).

Along with geographical and organizational proximity, we found the reduction of cognitive and social distances through another CIP success condition: having

continuous communication. For example, in the two Montreal community networks that we observed in-depth, individual representatives from diverse organizations met monthly and in some cases fortnightly to identify problems in the community to collectively tackle, and brainstorm ideas that were narrowed down to align with strategic priorities, including healthy eating and physical activity. The strategic priorities were then used to develop proposals that were submitted to QeF and other funders, for obtaining resources to implement the strategies over the period 2014–2017. Informants highlighted that it took time for them to deepen their own understanding and develop a shared view of problems to engage effectively with the political and sociocultural levers in their own organizations and communities. The quote below, from an individual who had represented early childhood organizations for over five years in one of the community networks (NDG) is illustrative of cognitive changes that have occurred [

99]:

Now I feel like we understand what we are working on together better. At first when I went back to my organization, I could not explain what the [community network] was doing. But now with all the time we have spent together we understand each other better … and what we are working for.

Informants noted that despite initial differences, particularly between decision-makers from government, the Chagnon Foundation, and community groups, goals began to converge, in part shaped by social proximity between individual representatives from the various sectors who interacted and socialized regularly over years. The quote below, from a community network member who had over a decade of experience in face-to-face interactions with government and philanthropy stakeholders, and held positions in various community organizations during the period of the study, illustrates the reduction in social distance that had also been occurring [

100]:

Sometimes communities don’t feel comfortable sharing some types of information with QeF ... because sometimes you are working with some organizations and there is limited money ... and you are not sure what they will use that information for [...] At first people didn’t trust QeF ... the Chagnon Foundation ... There was even a book about how rich people like Mr. Chagnon don’t pay their taxes ... ‘Ces riches qui ne paient pas d’impôt’ [Our translation: These rich people who do not pay taxes] ... But when you see him [Mr. Chagnon] you can see he has a good heart. He believes in this cause.

Here, the trust that stakeholders developed in Mr. Chagnon at the individual level (social proximity) enabled trust in the foundation he had created and, in turn, in the work of QeF. Changes in cognitive and social proximity that we observed at the community level are also suggestive of institutional level changes for convergence. A community development agent reflected that crafting and implementing strategies collectively across sectors in his region had become the norm [

101]:

It was simple [for those that used to work in silos] ... [now] we have had to deal with complexities, but now we are better off … We realized the synergies from such concerted efforts, although complexities arose—there were so many issues that needed to be dealt with … When people are put together in committees from the various groups working on the different issues, they see the synergies. For example, they see the links between physical activity and crime prevention. Some programs that initially focused on getting youth into sports also prevent them from getting into crime ... Even after QeF ends, we will not go back to working alone in silos.

However, beyond anecdotal accounts such as this one, claims of such change were not possible to ascertain when we turned our attention to explore another condition that Kania and Kramer (2011) note as necessary for successful CIPs: shared measurement systems.

3.3. Need for Development of Measurement Systems in the Long-Term: Quebec Presently

Measurement systems are a means for organizations to operationalize the vision of change that varies from one institutional sector to another (e.g., economic profit for business, social development for community organization), and guide them in specifying which problems they cognitively consider important, and the incentive structures and routines to use for reaching and measuring their progress. Agreement on measurement and reporting enables stakeholders to hold each other accountable and learn from each other’s successes and failures [

102]. In the Quebec case, a province-wide measurement framework provided cognitive guidance to decision-makers about what impacts were being targeted (

Table 7).

The measurement framework specified five categories of data that QeF encouraged each community network to gather for decision-makers to analyze in diagnosing problems, and in formulating and implementing strategies for achieving desired educational and health outcomes related to obesity reduction (e.g., improved self-concept among youth). Whereas socio-demographic data, and the data on economic and physical settings of communities, as well as on organizations in partnerships were largely quantitative, others such as behaviors; political and sociocultural contexts of communities; and opportunities, levers, resources and barriers faced in the community for influencing change were qualitative and had the least developed measures specified [

103]. Some evidence was provided about health and educational outcomes desired from the decades-long government-foundation partnership [

104,

105]. However, as an economic analysis of the partnership pointed out, there had been a lack of baseline measurement of largely qualitative factors [

106], such as social relationships, which some evaluations suggested were important for explaining which networks successfully brought about desired changes in outcomes [

96].

During interviews and observations of collaboration processes, decision-makers anecdotally noted qualitative factors as being what differentiated community networks that successfully addressed their communities’ problems from others, although we observed that decision-makers found it difficult to specify, assess and disseminate information about such qualitative factors. QeF coordinators working with multiple community networks raised the “important issue” of “how to treat qualitative data” [

107], with the following note about the need for frameworks to guide decision-makers in communities to gather and use such data:

Just as in conducting research, the [community networks] need to be guided by the questions that they are looking to answer, and a framework that helps them prioritize what data is pertinent or not. Currently they often gather a lot of data that is not relevant, so they end up developing long profiles that even they don’t use.

The lack of frameworks and measures of qualitative factors is a problem in sustaining the engagement of current stakeholders, such as government, or further engaging others, such as businesses or potential funders for collective impact. In the Quebec case, informants noted that one of the reasons for lack of engagement by stakeholders from business is that the benefits of engagement are unclear to them. Anecdotes may not be enough to engage such stakeholders, who may be interested in measurable data that align with their institutional norms, for convincing them to invest time and other resources in collective efforts. A community group leader noted the following [

99]:

But there is still a problem of measuring qualitative indicators … We need to find some ways to present such information to leaders from other sectors that makes them see how they can benefit if we work together.

Presently, in the Quebec case, despite the efforts made over the decade or so, institutional distance has persisted between the government-foundation partnership and some community-level leaders. Some among the latter perceive the former as being more focused on economic cost-cutting priorities and bureaucratic accountability measurements and processes, rather than the social needs of communities [

108]. There are also distances between the respective strategies of the businesses and community networks, with the former having been relatively less involved in QeF related initiatives and the face-to-face interactions. While QeF seeded some provincial level business initiatives, such as a program called Melior to engage food industry corporations to make their offerings healthier, individuals from businesses—even those at the community level—have largely been absent from the collective strategy-making and face-to-face interactions that have been ongoing at the community level. For example, by 2011 only 1% of 2923 QeF partner organizations were from the private sector [

41]. There has also been limited participation by individuals from business in regional level mobilization efforts that QeF had also been funding, for example, through the

Système alimentaire montréalais (SAM), a cross-sectoral network of over 30 organizations promoting a healthy food system in the city of Montreal [

109]. Whereas food business representatives have been invited to participate in the SAM, they have not been as engaged—measured through meeting attendance—as other community stakeholders. In our model, we depict this as divergence in strategies of decision-makers from different institutional sectors, denoted by Stakeholder #N

1,1 (e.g., business or government leader, focused on economic priorities such as balancing budgets) and Stakeholder #N

2,2 (e.g., community leader, focused on social priorities related to poverty in their community) in

Figure 2. The institutional distance between such stakeholders is represented in

Figure 2, with negative

institutional proximity (

IP) tending towards divergence.

Further, there have been fissures in existing cross-sector partnerships, also partly attributed to limitations in measurement and having information that can be used to engage stakeholders. For example, we found that current divergence in the strategies and partnership between the government and the Chagnon Foundation is partly related to challenges of measuring and illustrating qualitative concepts, as well as showing impacts that a market-oriented government desired as it cuts budgets. The following is an excerpt from the President of the Chagnon Foundation, Jean-Marc Chouinard [

110]:

We at the [Chagnon Foundation]—like others wishing to “change the world” for the better one small or medium step at a time—wish to learn from our successes and embrace the learning that comes from more deeply understanding how and why something isn’t working as expected … And governments’ short-term view is driven by a deep sense of intolerance to risk. This difference in risk tolerance suggests that a full partnership with government for a society-changing initiative can be difficult. Especially when it comes to supporting innovation… If the outcome of a project includes something like “creativity,” it is possible to succumb to the notion that this is a nice word but too risky to support. New approaches are, by nature, approaches with uncertain outcomes, and they should not be supported based on outcome objectives. Philanthropy can, for example, put time and energy into figuring out exactly how to research, operationalize, and measure “creativity” or innovation. There is so much to learn from these initiatives. But it is not easy for government to justify investing in a project that risks doing things wrong or even right, but with insufficient data in terms of accountability.

Despite a desire by the Chagnon Foundation for another multi-year period of formal partnership with the government, and negotiations that ensued towards the latter part of the 2007–2017 period, the government-foundation partnership that QeF was part of is ending, as initially stipulated (as not all the earmarked funding for the period was expended, some activities supported by the partnership will be funded into 2019). We conceptualize the difference between decision-makers in the private foundation and the government as institutional distance between the two stakeholders.

The institutional distance between the Chagnon Foundation and the Quebec government also illustrates a broader challenge of differences between the timeframes and related measures of progress among stakeholders from different institutional sectors, for them to stay engaged. Dr. Emmett Carson, founding CEO and President of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, the largest community foundation in the U.S. highlighted the need for process evaluation frameworks that consider differences in timeframes across decision-makers from different sectors [

111]:

If I’m on a year-to-year budget at a corporation [working with other stakeholders in a partnership], and someone’s got to make the case, what do they need in hand to go back and make that case? [What is needed is] very different from a foundation that started out by saying we’re making a 3-year grant.

Consistent with other informants in our study, Dr. Carson noted that frameworks are needed that specify short-term measures for informing stakeholders such as businesses or politicians, who need quick successes aligned with business and election cycles, respectively, and medium- and long-term measures for other stakeholders, such as foundation leaders, newly-elected politicians, and community workers to sustain their personal, organizational, and institutional engagement in crafting and implementing strategies for collective impact.

We also find that, in the Quebec case, while proximity was previously enabled among some stakeholders (denoted by the strategies of Stakeholder #N

1,2 and Stakeholder #N

2,1 in

Figure 2), for them as well, there is need to address the issue of conceptualizing and measuring qualitative factors during processes for collective impact. In October 2015, it was announced that the Chagnon Foundation was partnering with a key partner, Centraide/United Way of Greater Montreal and other organizations in a regional-level Collective Impact Project (CIP) that explicitly adopted the collective impact framework (Stakeholder #N

1,2 in

Figure 2). The CIP “aims to increase the impact of collective action and achieve measurable and significant outcomes in the reduction of poverty” in Montreal [

42]. The Chagnon Foundation, Centraide/United Way of Greater Montreal, and other partners—including seven other foundations: the Silver Dollar Foundation, Foundation of Greater Montreal, J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, Mirella and Lino Saputo Foundation, Pathy Family Foundation, Marcelle and Jean Coutu Foundation, and Molson Foundation—pooled

$22.5 million over five years in this new regional-level initiative, inviting geographically-defined communities in Montreal “to experiment, innovate and find new ways to accelerate change”. This exemplifies the type of formal collaboration that Hilary Pearson, President and CEO of Philanthropic Foundations Canada (PFC) predicted would emerge, when interviewed in 2013, as stakeholders learn to overcome organizational and other related barriers. In explicitly adopting collective impact, Centraide/United Way of Greater Montreal serves as a

backbone organization for the CIP. Having Centraide as the backbone organization signifies a departure from the 2007–2017 approach of having QeF, which the Chagnon Foundation created as an NGO for its government partnership, as the backbone for community level organizations. Notably, there may be closer institutional proximity between Montreal’s community organizations, businesses, and Centraide, given prior organizational proximity between them. Centraide was created in 1975 by merging a number of charitable organizations that served different community sectors, at the request of donor businesses that preferred interacting with one focal organization [

112]. Thus, Centraide already has a history of engaging with these diverse stakeholders, including businesses, thereby potentially addressing the lack of business engagement that has characterized efforts hitherto. Additionally, the Chagnon Foundation’s flagship NGO, QeF is continuing to advance the GAP’s healthy lifestyles agenda, although it is being reorganized to focus more on providing support, including funding, for regional-level backbone organizations. In Montreal, such backbone organizations supporting healthy eating, specifically, are exemplified by the SAM (Stakeholder #N

2,1 in

Figure 2). The SAM, itself, was transitioning as of 2017 to become Montreal’s food policy council, networking multiple organizations spanning institutional sectors [

113].

4. Discussion

The Quebec case we studied highlighted that despite successes in convening diverse stakeholders and initiating formal organizational partnership networks to address complex societal problems, challenges remain in having measurement systems to guide and assess longer-term processes for collective impact. Emphasis is placed on cause-effect variables and outcome measures, with process measures receiving relatively limited attention. Yet, the nonlinearity of collective processes among diverse stakeholders for effectively addressing complex societal problems often makes it futile to attempt establishing direct cause-effect attributions that have characterized top-down approaches. Thus, in addition to evaluating how strategies and related interventions impact outcomes like obesity and weight-related problems, it is important to also focus upstream, for a deeper understanding of how factors, such as the multiple dimensions of proximity, shape, and are shaped by, strategies and partnership structures, ultimately contributing to collective impact in addressing complex problems. While such efforts at enabling proximity may seem mundane, they are among the “minor” [

3], yet “high leverage”, factors that decision-makers can use in potentially causing disproportionate positive changes in complex systems [

32].

Our findings in the Quebec case are consistent with challenges noted in assessing qualitative, long-term process changes, for example, by Margaret Hempel, a director at the Ford Foundation [

114]:

I think the focus on impact measures [in the short-term] is a mistake. We take a longer-term view and establish long-term relationships ... Such a long-term view ends up developing institutions. For example, Ford foundation support was instrumental in the development of demography and women’s studies as fields in many educational institutions ... [Yet] it is challenging to measure efforts at changing norms and culture.

Under different circumstances in Quebec, or in other contexts, proximities between stakeholders and the convergence of strategies and partnership structures might differ from what we found in the case presented. For example, some unanticipated outcomes have emerged from the two communities that we studied. While both communities applied to participate in the new Montreal Collective Impact Project, one was selected (Centre-Sud), while the other was not (NDG). Yet, food system organizations in the two communities are currently collaborating on other projects, including another collective impact effort with a national level backbone organization. Such outcomes provide the basis for comparative studies that we have initiated. In all cases, however, a shared measurement system will be vital to capture changes in geographical, organizational, cognitive, social, and institutional proximities between stakeholders for collective impact. Experiences have shown that focusing a priori on developing a shared measurement system in CIPs can be limiting and, as such, systems should be emergent [

32]. Emergent measurement systems enable learning, and allow diverse stakeholders to better visualize the synergies with others.

Our experience in conducting this study suggests that decision-makers across sectors—academics and practitioners alike—are empowered in efforts to collectively innovate for solving complex problems when they can better assess efforts to enable various dimensions of proximity among groups of stakeholders that they convene, in the short-, medium-, or long-term, in any specific geographic location. In Quebec, while the processes for collective impact to address the complex societal problems related to obesity are in motion, it is not yet clear the extent to which some stakeholders, such as decision-makers from business, with their different systems of measurement and incentive structures will be engaged in the regular stakeholder interactions that are occurring in communities. In efforts to change individual and collective mindsets, social relationships, organizations, and institutions for desired outcomes, decision-makers in partnerships for collective impact in Quebec and elsewhere need to address the following question: What approaches are effective in enabling the multiple dimensions of proximity between diverse stakeholders, including community, businesses and government, for the emergence of collective impact?

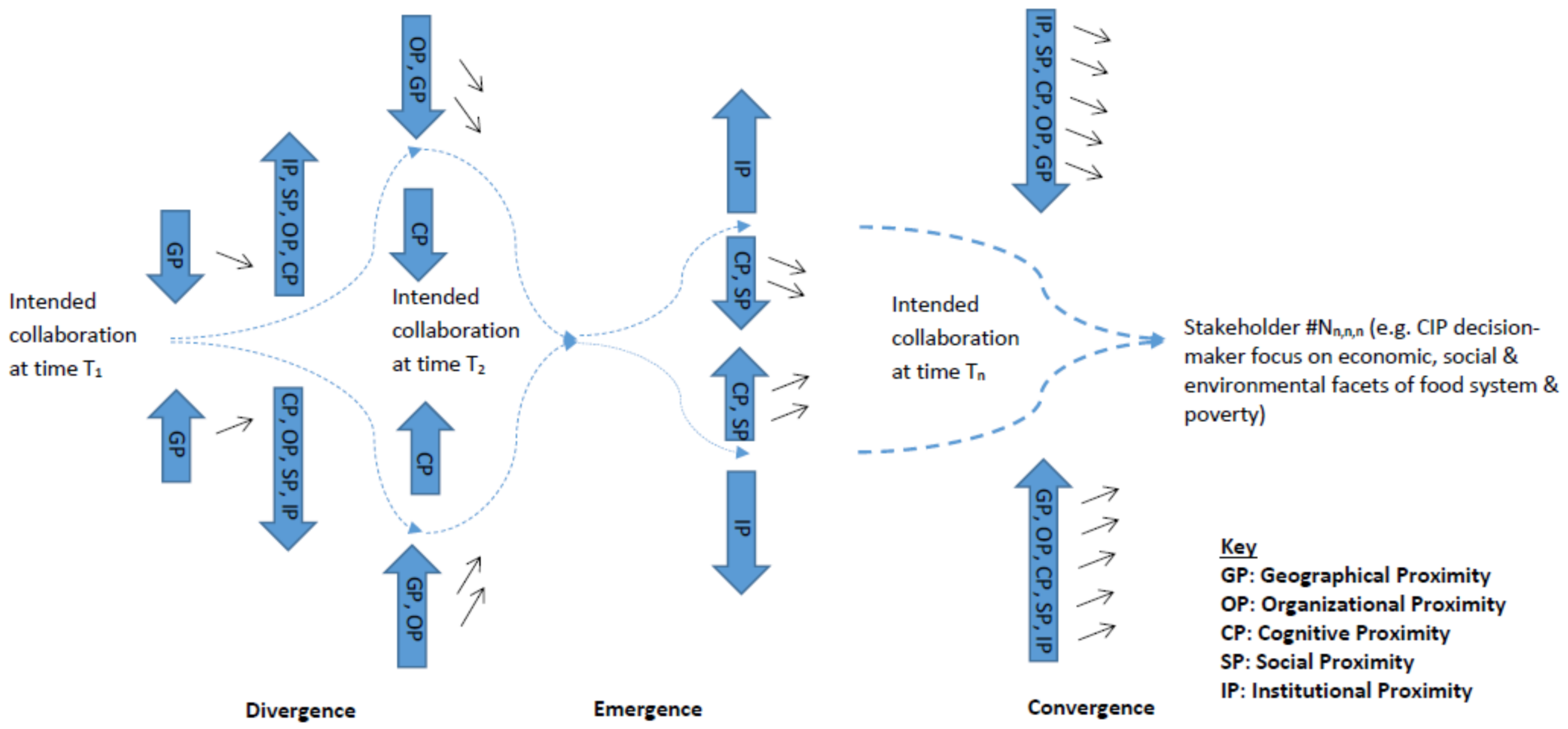

In ongoing processes, decision-makers can use the proximity framework to specify and measure relevant factors—notably the seemingly intangible ones, such as cognitive, social, and institutional proximity—at baseline, and their short-, medium-, and long-term changes, linking them with evolving intermediate outcomes and long-term impacts that diverse stakeholders are concerned with. In our stylized multidimensional model, over multiple iterations, the various dimensions of proximity attract stakeholders from across public, private, and community sectors towards convergence in strategies and partnerships for collective impact in addressing the root causes of poverty and food system related problems (denoted by the strategy of Stakeholder #N

n,n,n in

Figure 3). The number of iterations for convergence of strategies and partnerships structures depends on which dimensions of proximity are enabled.

Similar to ongoing proximity research in other domains, we propose formally testing our multidimensional model in future collective impact research, which will be crucial for analyzing relationships between proximity and processes and outcomes in Quebec and beyond. Based on the Quebec case studied, we make a number of propositions, summarized in

Table 8.

Measures of proximity will be captured during different phases of collaboration between diverse stakeholders from across institutional sectors, to analyze their interactions, and show how learning and innovation emerge over time for collective impact. Proposed research on the emergence of common indicators will also measure relationships between proximity variables and outcomes that they have been associated with in research on learning and innovation, such as knowledge exchange, innovative performance, and joint projects and alliances.

Table 9 summarizes examples from research we are pursuing in testing the model developed here, as we analyze the proximity between pairs of stakeholders—ego (e.g., community leader) and alter (e.g., business person/philanthropy leader)—in CIPs and other types of cross-sector and interdisciplinary partnerships, as well as related outcomes.

Recent proximity studies are adopting multiple methodological approaches to explore how the dimensions of proximity interact to stimulate effective learning in partnerships for innovation [

44,

61]. Ethnographic studies show that cognitive and social proximity are important for successful collaboration in business development, technology acquisition, and innovation [

127]. Others propose the use of longitudinal surveys to measure the different dimensions of proximity, to show their relationships over time [

61,

124]. We note that the advancements in mobile applications and other digital tools for collecting real-time data more cheaply and extensively provides opportunities for such proximity research. We will use text-mining and other digitally-enabled approaches to analyze data from online platforms, on people’s locations, organizational and institutional affiliations, as well as their understanding of problems and social relationships. We will also take advantage of mobile devices’ collaborative data collection possibilities for supporting stakeholders’ development of shared indicators and measurement systems for collective impact (through mobile apps, software development, etc.).

5. Conclusions

We have contributed to addressing critiques of the collective impact framework by applying concepts from the proximity literature to the Quebec case. We have further developed the theoretical foundation and practical implementation of collective impact based on empirical evidence from stakeholders that span public, private, and civil society sectors [

2]. Consistent with the use of proximity in analyzing learning and innovation in technological domains [

44,

45,

46], we found utility in the multidimensional proximity framework for explaining processes by which collective impact partnerships emerge, and can be sustained, for solving complex societal problems. We have also addressed noted limitations of the proximity literature [

61] through our analysis of diverse stakeholders, as opposed to relatively homogenous groups of actors from one social sector (e.g., scientists or professionals), and multiple proximity dimensions, as opposed to one. A critique of the prior proximity literature is the lack of real-time data and the use of measures, such as publications and patents as outcome variables, as that does not offer a complete picture of the effects of proximity on learning or innovation. Thus, another key contribution of this paper is in specifying a model for real-time analysis of relatively intangible factors related to partnership processes, such as stakeholders’ social relations, norms, and values, and for further exploration of linkages with outcomes, such as innovative performance. The model guides researchers and practitioners as they specify, gather, and make sense of such qualitative factors to sustain their efforts towards collective impact.

Our ongoing research will address some of the limitations of this study. For example, we were unable to capture the partnership processes that we analyzed in Quebec in real-time from its inception in the early 2000s. Future research, for example on the emerging CIP in Quebec, can gather real-time data by integrating our proposed model in assessment and evaluation plans. Additionally, while we did not have data for a more rigorous comparative analysis of the communities studied, future research can focus on such a comparison. Further, our future research will continue to integrate knowledge that has developed in parallel across the domains of economic geography, innovation, and philanthropy, in deepening the understanding and contributing to the theory and practice of partnerships for collective impact. For example, using the multidimensional proximity framework, geographers and economists, who may focus on relatively shorter-term geographical and related cost and efficiency factors impacting innovation, will collaborate with researchers in cognition, sociology, organizational studies, institutional theory, and other disciplines, to explore cognitive, social, organizational, and institutional factors that shape, and are shaped by, partnerships in the long-term. In conclusion, the agenda emerging from this paper is, in itself, an opportunity for closer proximity between diverse academic and practitioner stakeholders to address complex societal problems.