Toward Sustainable Development? A Bibliometric Analysis of PPP-Related Policies in China between 1980 and 2017

Abstract

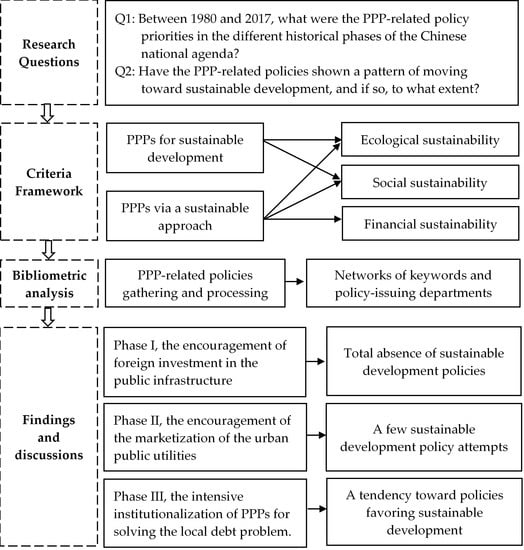

:1. Introduction

2. PPP-Related Policies and Sustainable Development

2.1. PPPs for Sustainable Development

2.2. PPPs via Sustainable Approach

3. Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. Phase I, 1980–1997: Encouragement of Foreign Investment and No Relevance to Sustainable Development

4.2. Phase II, 1998–2008: Promoting the Marketization of the Municipal Public Utilities and a Few Attempts to Encourage Sustainable Development

4.3. Phase III, 2009–2017: The Institutionalization of PPPs and an Obvious Tendency toward Sustainable Development

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The VFM test is a two-fold analysis conducted prior to the PPPs implementation. First, the calculation of the benchmark cost of providing the specified service under traditional procurement and, second, a comparison of this benchmark cost with the cost of providing the specific service under a PPPs scheme. More details see Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M. Are public private partnerships value for money? Evaluating alternative approaches and comparing academic and practitioner views. Accounting Forum. 2005, 29(4), 345-378.

- Law-lib Database is an influential Chinese database of laws and regulations, recording all the policies, laws, and regulations since 1949. It is available at the following link: http://www.law-lib.com/law/bbdw-zy.htm.

- The CPPPC was established by the MoF in December 2014. It is responsible for policy research, consulting training, information statistics, and the international cooperation of PPPs. The PPPs project database, expert database, consultancy organization database, and policy database are available at this official website: http://www.cpppc.org/zh/pppzczd/index.jhtml.

- The PPPs column is a special column built by the NRDC. A second source of PPPs projects, example PPP cases, and PPP-related policies are available at this official website: http://tzs.ndrc.gov.cn/zttp/PPPxmk/.

- LGFVs is short for local government financing vehicles. As quasi-government entities, LGFVs are used by local governments to borrow from banks or issue bonds, while the money collected is used in urban infrastructure areas. For more details, see [70].

- SATI 3.2 is a domestic tool designed by researchers of Zhejiang University, China for bibliographic statistical analysis. More details see Liu, Q.; Ye, Y. A Study on Mining Bibliographic Records by Designed Software SATI: Case Study on Library and Information Science. Journal of Information Resources Management. 2012, 1, 50–58. (In Chinese)

- A UCINET 6 tutorial by Bob Hanneman and Mark Riddle is available at the following link: http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/. More details see Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G. and Freeman, L.C. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies. 2002.

- The Girvan–Newman’s algorithm detects communities by progressively removing edges from the original graph. The algorithm removes the “most valuable” edge, traditionally the edge with the highest betweenness centrality, at each step. As the graph breaks down into pieces, the tightly knit community structure is exposed and the result can be depicted as a dendrogram. More details are available at the following link: https://networkx.github.io/documentation/latest/reference/algorithms/community.html.

- In Phase III, several PPPs policies were jointly issued by more than 10 departments. For the better effect of visualization, for each policy, we only presented the connection between the leading policy-issuing department and the other non-leading departments, and did not present the connection amongst the other non-leading departments.

- We selected 1980 as the starting year for analysis, as it was at that time that China started to engage in PPPs development under the reform and opening-up policies.

- In 2014, the MoF created a policy entitled “Guidance on Regulating PPPs Contract Management” and defined the concept of ‘social capital’ (she hui zi ben) in detail. Social capital refers to enterprises duly organized, validly existing, and in good standing as a legal person under the law of the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C.), consisting of domestic private enterprises, SOEs, and foreign enterprises. However, LGFVs affiliated with native local governments and other SOEs controlled by native local governments are not allowed to act as the social capital to participate in PPP projects launched by native local governments. For example, regarding the SOEs controlled by the Beijing municipal government. This company cannot take part in PPPs projects launched by the Beijing municipal government, for it is not ‘social capital’ relative to the Beijing municipal government. However, it can participate in PPPs projects launched by the Shanghai municipal government, because the company is not affiliated to or controlled by the Shanghai municipal government.

- Considering the length of the paper, the policymaking departments that issued only one or two PPP-related policies during Phase III are not listed in the Table. The details are as follows. (1) The policymaking departments that issued two PPP-related policies during Phase III consisted of the National Office for Agricultural Comprehensive Development, the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, the China Railway Corporation, the National Bureau of Statistics, the State Administration of Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense, the State Council Poverty Alleviation Office, the General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine, and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage. (2) The policymaking departments that issued only one PPP-related policy during Phase III consisted of the National Government Offices Administration, the Supreme People’s Court, the Chinese Academy of Engineering, the State Administration of Work Safety, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the Ministry of Justice, the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration, the China Earthquake Administration, the State Administration of Grain, the General Administration of Customs, the State Intellectual Property Office, the State Food and Drug Administration, the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, the Agricultural Development Bank of China, the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Ministry of Public Security, and the China Meteorological Administration.

- Some examples can be seen in the policy of “Notice on Strengthening LGFVs Management” issued by the State Council in 2010, the policy of “Advice on Strengthening Management of Local Government Debts” issued by the State Council in 2014, and the policy of “Notice on Budgetary Controlling and Cleaning up the Stock of Local Government Debt” issued by the MoF in 2014. The policy of “Notice on Strengthening LGFVs Management”, issued by the State Council in 2010, clearly required using PPPs for solving local government debt problems. The policy of “Notice on Promoting Debt for Equity swap by Using Governmental Funds”, issued by Commission of National Development and Reform, raised the guidance to swap local government debt into equity in PPPs.

- In 2015, the State Council issued a policy entitled “Guidance on Promoting Sponge City Construction” to minimize the side effects of urban construction on the ecological condition and to accelerate the absorption and use of rainfall. The term ‘sponge city’ refers to cities that can adapt flexibly, similar to sponges, to changes in the environment, such that they absorb, store, permeate, and purify rainwater and are able to make use of stored water when needed.

References

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M. Accounting for public private partnerships. Account. Forum 2002, 26, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Economic Commission for Europe. Draft Guiding Principles on People-First Public-Private Partnerships for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Conference Room Paper Submitted by the Secretariat. November 2017. Available online: http://www.unece.org/ppp/wpppp1.html (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- United Nations. Agenda 21. United Nations Conference on Environment & Development. Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. China’s National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2016. Available online: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/zt_674979/dnzt_674981/qtzt/2030kcxfzyc_686343/ (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- de Castro e Silva Neto, D.; Cruz, C.O.; Rodrigues, F.; Silva, P. Bibliometric analysis of PPP and PFI literature: Overview of 25 years of research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 06016002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G.; Zhu, D. Public–private partnership in Public Administration discipline: A literature review. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.; Greve, C. Contemporary public–private partnership: Towards a global research agenda. Financ. Account. Manag. 2018, 34, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhao, X.B. Critical factors on the capital structure of public-private partnerships projects: A sustainability perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, N.A.; Tharun, D.; Laishram, B. Infrastructure development through PPPs in India: Criteria for sustainability assessment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 708–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Tam, E.K. Indicators and framework for assessing sustainable infrastructure. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2005, 32, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, O.O. A service-oriented framework for sustainability appraisal and knowledge management. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. (ITcon) 2005, 10, 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. Governing public-private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjärstig, T. Does Collaboration Lead to Sustainability? A Study of Public–Private Partnerships in the Swedish Mountains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Tam, V.W.; Gan, L.; Ye, K.; Zhao, Z. Improving sustainability performance for public-private-partnership (PPP) projects. Sustainability 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.; Enserink, B. Public–private partnerships in urban infrastructures: Reconciling private sector participation and sustainability. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colverson, S.; Perera, O. Sustainable Development: Is There a Role for Public–private Partnerships? International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD): Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://www.iisd.org/library/sustainable-development-there-role-public-private-partnerships-summary-iisd-preliminary (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Powell, J. PPPs and the SDGs: Don’t Believe the Hype. University of Greenwich Working Paper. , 2016. Available online: http://gala.gre.ac.uk/16843/ (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Hodge, G.A.; Greve, C. PPPs: The passage of time permits a sober reflection. Econ. Aff. 2009, 29, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.T.; Hamburg, S.P.A.; Janetos, A.C.A.; Moss, R.H.A.; Dixon, J.A.A. Protecting Our Planet, Securing Our Future: Linkages among Global Environmental Issues and Human Needs; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1998.

- Barlow, J.; Roehrich, J.; Wright, S. Europe sees mixed results from public-private partnerships for building and managing health care facilities and services. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stigson, B. Paper on Partnerships Involving the Private Sector. OECD and WBCSD. Conference of EECCA Environment Ministers and their partners. October 2004. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/33811690.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2018).

- Oktavianus, A.; Mahani, I. A Global Review of Public Private Partnerships Trends and Challenges for Social Infrastructure. In MATEC Web of Conferences (Volume 147, p. 06001). EDP Sciences, 2018. Available online: https://www.matec-conferences.org/articles/matecconf/abs/2018/06/matecconf_sibe2018_06001/matecconf_sibe2018_06001.html (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Infrastructure Partnership Australia. Australian Infrastructure Investment Report 2015; Perpetual: Sydney, Australia, 2015. Available online: http://www.urbanaffairs.com.au/downloads/2015-10-29-2.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2018).

- Planning Commission. Annual Report (2007–08). Government of India. Available online: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/ar_0708E.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- Planning Commission. Annual Report (2008–09). Government of India. Available online: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/ar0809eng.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- Liebe, M.; Pollock, A. The experience of the private finance initiative in the UK’s National Health Service. University of Edinburgh, Centre for International Public Health Policy: Edinburgh, UK, August 2009. Available online: https://www.allysonpollock.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/CIPHP_2009_Liebe_NHSPFI.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Roehrich, J.K.; Lewis, M.A.; George, G. Are public–private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 113, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, B. Public Private Partnerships and Sustainability Principles Guiding Legislation and Current Practice. Dublin Institute of Technology, 2004. Available online: https://arrow.dit.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=futuresacrep (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Global Green Growth Institute. Green Public-private Partnerships for Public Infrastructure in Mongolia: PPP Model and Technical Guidelines for Green Education Buildings. 2016. Available online: http://gggi.org/site/assets/uploads/2017/02/2016-Green-Public-Private-Partnerships-for-Public-Infrastructure-in-Mongolia-1.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Caldwell, N.D.; Roehrich, J.K.; George, G. Social value creation and relational coordination in public-private collaborations. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 906–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C. Post-contractual lock-in and the UK private finance initiative (PFI): The cases of National Savings and Investments and the Lord Chancellor’s Department. Public Adm. 2005, 83, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivleniece, I.; Quelin, B.V. Creating and capturing value in public-private ties: A private actor’s perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.A. The risky business of public–private partnerships. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2004, 63, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JETRO. Public Private Partnerships in Australia and Japan: Facilitating Private Sector Participation. Japan External Trade Organization, Asia and Oceania Division, Overseas Research Department, August 2010. Available online: https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/en/reports/survey/pdf/2010_01_other.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Planning Commission, India. Faster, Sustainable and More Inclusive Growth: An Approach to the Twelfth Five Year Plan. Working Papers, id: 4452, eSocialSciences. New Delhi: Planning Commission, Government of India; 2011. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ess/wpaper/id4452.html (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M. Public private partnerships and public procurement. Agenda J. Policy Anal. Reform 2007, 14, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- HM Treasury. PFI, Meeting the Investment Challenge; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2003.

- HM Treasury. Draft Value for Money Appraisal Guide; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2004.

- Cruz, C.O.; Marques, R.C. Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Partnerships Victoria. Guidance Material: Practitioners’ Guide; Department of Treasury and Finance: Melbourne, Australia, 2001.

- Partnerships Victoria. Guidance Material: Public Sector Comparator, Supplementary Technical Note; Department of Treasury and Finance: Melbourne, Australia, 2003.

- British Columbia Ministry of Finance. Capital Asset Management Framework: Guidelines; British Columbia Ministry of Finance: Victoria, UK, 2002.

- Department of the Environment and Local Government. Public-Private Partnership Assessment Guidance Note Four; Department of the Environment and Local Government: Dublin, Ireland, 2000.

- Netherlands Ministry of Finance. PPP and Public Procurement; PPP Knowledge Centre: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2001.

- Xu, Y.; Yeung, J.F.; Jiang, S. Determining appropriate government guarantees for concession contract: Lessons learned from 10 PPP projects in China. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2014, 18, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobina, E.; David, H. Problems with Private Water Concessions: A Review of Experience; Public Service International Research Unit: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Walker, B.C. Privatisation: Sell off or Sell out? The Australian Experience; ABC Books for the Australian Broadcasting Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2000; ISBN 0 7333 0797 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Chan, A. Revelation of the Channel Tunnel’s failure to risk allocation in Public-Private Partnership projects. China Civ. Eng. J. 2008, 41, 97–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, T. BOT Financing Research—Take ShaJiao B Power Plant as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Jinan University, Jinan, China, 2006. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, E.; Ding, Y. Applying centrality measures to impact analysis: A coauthorship network analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Himelboim, I.; Smith, M.; Shneiderman, B. Tweeting apart: Applying network analysis to detect selective exposure clusters in Twitter. Commun. Methods Meas. 2013, 7, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, Q.B.; Zhong, D.P.; Ye, X.T. The pattern of policy change on disaster management in China: A bibliometric analysis of policy documents, 1949–2016. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Laville, F. Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics 1991, 22, 155–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Su, J.; Xie, X.; Ye, X.; Li, Z.; Porter, A.; Li, J. A bibliometric study of China’s science and technology policies: 1949–2010. Scientometrics 2015, 102, 1521–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wong, C.W.; Miao, X. Evolution of government policies on guiding corporate social responsibility in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtial, J. A coword analysis of scientometrics. Scientometrics 1994, 31, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, N.; Monarch, I.; Konda, S. Software engineering as seen through its research literature: A study in co-word analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chowdhury, G.G.; Foo, S. Bibliometric cartography of information retrieval research by using co-word analysis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2001, 37, 817–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Ke, Y.J.; Xie, J. Public-private Partnership Implementation in China. Taking Stock of PPP and PFI around the World; Certified Accountants Educational Trust: London, UK, 2012; pp. 29–36. Available online: https://study.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/ACCA%20on%20PPPs%20around%20the%20world.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Chen, C.; Doloi, H. BOT application in China: Driving and impeding factors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Chung, J.; Lee, D. Risk perception analysis: Participation in China’s water PPP market. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.X. Five periods of PPPs development in China. Water Ind. Mark. 2014, 7, 55–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mu, R.; De Jong, M.; Koppenjan, J. The rise and fall of Public–Private Partnerships in China: A path-dependent approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Qiang, M.S. Political risks and sovereign risks in Chinese BOT/PPP projects: Case studies. Chin. Bus. Invest. Financ. 2005, 1, 50–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.L. Issues and solutions of financing urban infrastructure projects. Urban Manag. Sci. Technol. 2007, 2, 34–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lieberthal, K.; Oksenberg, M. Policy Making in China: Leaders, Structures, and Processes; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Li, D. Policy change and policy learning in China’s public-private partnership: Content analysis of PPP policies between 1980 and 2015. Chin. Public Adm. 2017, 102–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.R.; Su, G.C.; Li, D. The rise of public-private partnerships in China. J. Chin. Gov. 2018, 3, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Public Private Partnerships Center. Quarterly Report of National PPPs Projects Development. 26 October 2018. Available online: http://www.cpppc.org/zh/pppjb/7450.jhtml (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Shao, W.W.; Zhang, H.X.; Liu, J.H.; Yang, G.Y.; Chen, X.D.; Yang, Z.Y.; Huang, H. Data integration and its application in the sponge city construction of China. Procedia Eng. 2016, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M.K. The Governance of Contractual Relationships in Public-Private Partnerships. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2004, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sun, W. PPP application in infrastructure development in China: Institutional analysis and implications. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, A.E.; Vining, A.R. Assessing the economic worth of public–private partnerships. In International Handbook on Public–Private Partnerships; Hodge, G.A., Greve, C., Boardman, A.E., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, G. Public-Private Partnership: Ambiguous, Complex, Evolving and Successful: Keynote address to Global Challenges in PPP: Cross-Sectoral and cross-Disciplinary Solutions? Universiteit Antwerpen: Antwerpen, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yescombe, E.R. PPPs and project finance. In The Routledge Companion to Public-private Partnerships, 1st ed.; De Vries, P., Etienne, B.Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 227–246. [Google Scholar]

| Sustainability | PPPs for Sustainable Development | PPPs via a Sustainable Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Ecological sustainability | Policies that encourage PPPs to be used for ecological/environmental protection projects. | Policies that demand that PPPs be used via an environmentally friendly approach, such as the innovative use of a resource or environmentally friendly technologies. |

| Social sustainability | Policies that encourage PPPs to be used for social infrastructure and service projects. | Policies that demand that PPPs be used via a transparent and due process approach. |

| Financial sustainability | Not applicable. | Policies that demand that PPPs be used via a financially sustainable approach, such as the VFM test and the financial affordability test and forbidding government guarantees |

| Phase I: 1980–1997 | Phase II: 1998–2008 | Phase III: 2009–2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Number | Year | Number | Year | Number |

| 1980 | 2 | 1998 | 1 | 2009 | 3 |

| 1982 | 1 | 1999 | 3 | 2010 | 5 |

| 1985 | 1 | 2000 | 1 | 2011 | 2 |

| 1986 | 3 | 2001 | 3 | 2012 | 2 |

| 1988 | 3 | 2002 | 10 | 2013 | 5 |

| 1990 | 2 | 2003 | 4 | 2014 | 26 |

| 1992 | 1 | 2004 | 7 | 2015 | 48 |

| 1993 | 1 | 2005 | 2 | 2016 | 72 |

| 1995 | 3 | 2007 | 1 | 2017 | 85 |

| 1996 | 1 | ||||

| 1997 | 1 | ||||

| 18 Years | 19 | 11 Years | 32 | 9 Years | 248 |

| Department | Number |

|---|---|

| State Council | 11 |

| Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation | 6 |

| State Development Planning Commission | 4 |

| State Administration of Industry and Commerce | 1 |

| Ministry of Construction | 1 |

| Ministry of Electric Power | 1 |

| Ministry of Transport | 1 |

| Department | Number |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Construction | 14 |

| Ministry of Commerce | 11 |

| State Council | 9 |

| National Development and Reform Commission | 6 |

| State Environmental Protection Administration | 2 |

| Ministry of Land and Resources | 2 |

| Ministry of Finance | 2 |

| State Economic and Trade Commission | 1 |

| Ministry of Water Resources | 1 |

| Ministry of Supervision | 1 |

| Department | Number |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Finance | 106 |

| National Development and Reform Commission | 73 |

| State Council | 68 |

| Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development | 34 |

| China Banking Regulatory Commission | 20 |

| Ministry of Land and Resources | 19 |

| Ministry of Transport | 17 |

| People’s Bank of China | 16 |

| Ministry of Agriculture | 16 |

| Ministry of Environmental Protection | 14 |

| Ministry of Water Resources | 12 |

| National Health and Family Planning Commission | 9 |

| State Forestry Administration | 8 |

| Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Commerce, China Securities Regulatory Commission | 7 |

| China Insurance Regulatory Commission, National Energy Administration, Ministry of Science and Technology | 6 |

| National Railway Administration, Civil Aviation Administration of China, China Development Bank | 5 |

| Ministry of Culture, State Administration of Industry and Commerce, Ministry of Education, State Oceanic Administration | 4 |

| National office for aging, General Administration of Sport, State Administration of Taxation, National Tourism Administration | 3 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Li, D.; Man, C. Toward Sustainable Development? A Bibliometric Analysis of PPP-Related Policies in China between 1980 and 2017. Sustainability 2019, 11, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010142

Chen C, Li D, Man C. Toward Sustainable Development? A Bibliometric Analysis of PPP-Related Policies in China between 1980 and 2017. Sustainability. 2019; 11(1):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010142

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Cheng, Dan Li, and Caixia Man. 2019. "Toward Sustainable Development? A Bibliometric Analysis of PPP-Related Policies in China between 1980 and 2017" Sustainability 11, no. 1: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010142