An Effective National Evaluation System of Schools for Sustainable Development: A Comparative European Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Primary education quality has been included among the United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals (MDG) as the second target; confirmed and implemented in the Sustainability Developments Goals (SGDs) of the Agenda 2030 it focuses on obtaining a quality education as a foundation to create sustainable development, but most important is the idea that access to inclusive education can help equip locals with the tools required to develop innovative solutions to the world’s greatest problems;

- The OCED has been involved in education quality for many years, as PISA test was first introduced in 2000;

- In 2001, the European Council identified a fresh set of challenges which must be met so that Europe can become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion through diversification, flexibility and deregulation of education systems. In 2009 and 2010, the European Commission went over the Lisbon Strategy and introduced ET 2020: a strategic framework in education and training and Europe 2020: a 10-year strategy for advancement of the economy of the European Union. A pillar of both these strategies is primary education quality improvement trough school autonomy and self-evaluation. Again, the conclusions of the council of 20 May 2014, on quality assurance supporting education and training, stimulate the commission to back up states in improving school evaluation [1,2].

2. Theoretical Framework

- internal evaluation: auto-analysis and auto-verification of the scholastic service;

- external evaluation: assessment by an external subject/body, primarily finalized to monitor and improvement;

- actions of improvement: planning and implementation, at school establishment level, of the interventions through the development of a plan;

- social accountability: publication and dissemination of the reached results, also using markers, indicators, reports, and comparative data, according to transparency, sharing, engagement and of promotion to the improvement of the service.

3. Research Methodology

- evolution of national evaluation systems, between 2015 and 2018 in countries belonging to Eurydice Network;

- improvement or reforms of national evaluation systems in countries where OECD-PISA 2015 outcome are unsatisfactory.

Is it possible to identify a single and synthetic parameter of evaluation (standardized test) as a measurement element of the existing relationship between school management tools (national system of evaluation) and quality of the system (students’ output)?

- detailed descriptions and overviews of national education systems;

- comparative thematic reports devoted to specific topics of community interest;

- factual reports on education, such as national education structures, school calendars, comparison of salaries, and of required taught time per country and educational level.

- external evaluation,

- internal evaluation,

- development plan,

- social accountability.

4. Results and Discussion

- 4.1

- Evolution of external and internal evaluation of schools within the national evaluation system.

- 4.2

- Considerations about the relationship between PISA 2015 results and national evaluation system development.

4.1. Evolution of External and Internal Evaluation of Schools

- bodies responsible for the evaluation (external and internal);

- focus of the evaluation (external and internal);

- frequency of evaluation activities (external and internal).

4.1.1. External Evaluation

- Establishment of the regional platform for the cooperation of education experts in the region dealing with quality assurance in general education (QA network) and addressing recommendations of the European Quality Assurance Reference Framework in general education, with the particular focus on the internal and external assessment of education;

- Synchronizing the work of this QA network with the work of the Education and Training 2020 Workgroups—Open Method of Coordination nominees—from the countries of the region;

- Establishment of an on-line regional platform offering possibilities for communication and sharing between experts.

- the achievement of the objectives set by management;

- the implementation of any corrective actions.

4.1.2. Internal Evaluation of Schools

- quality of teaching (evaluation of teachers and students);

- organization;

- leadership;

- management of economic resources;

- facilities.

4.1.3. Development Plan

4.1.4. Social Accountability

- defined indicators or common protocols, established at central level;

- standards chosen by each school.

4.2. Relationship between PISA 2015 Results and National Evaluation System Development

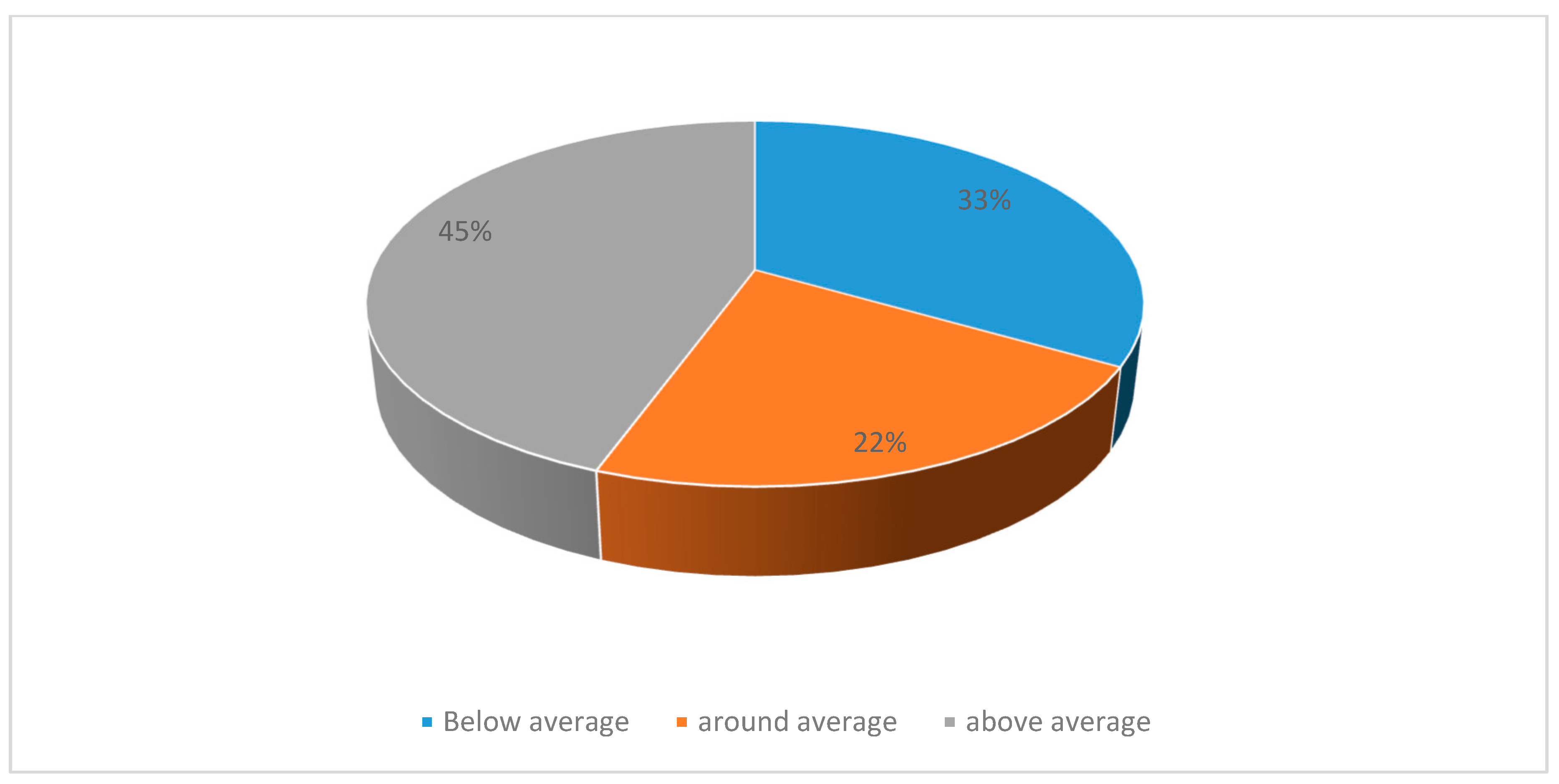

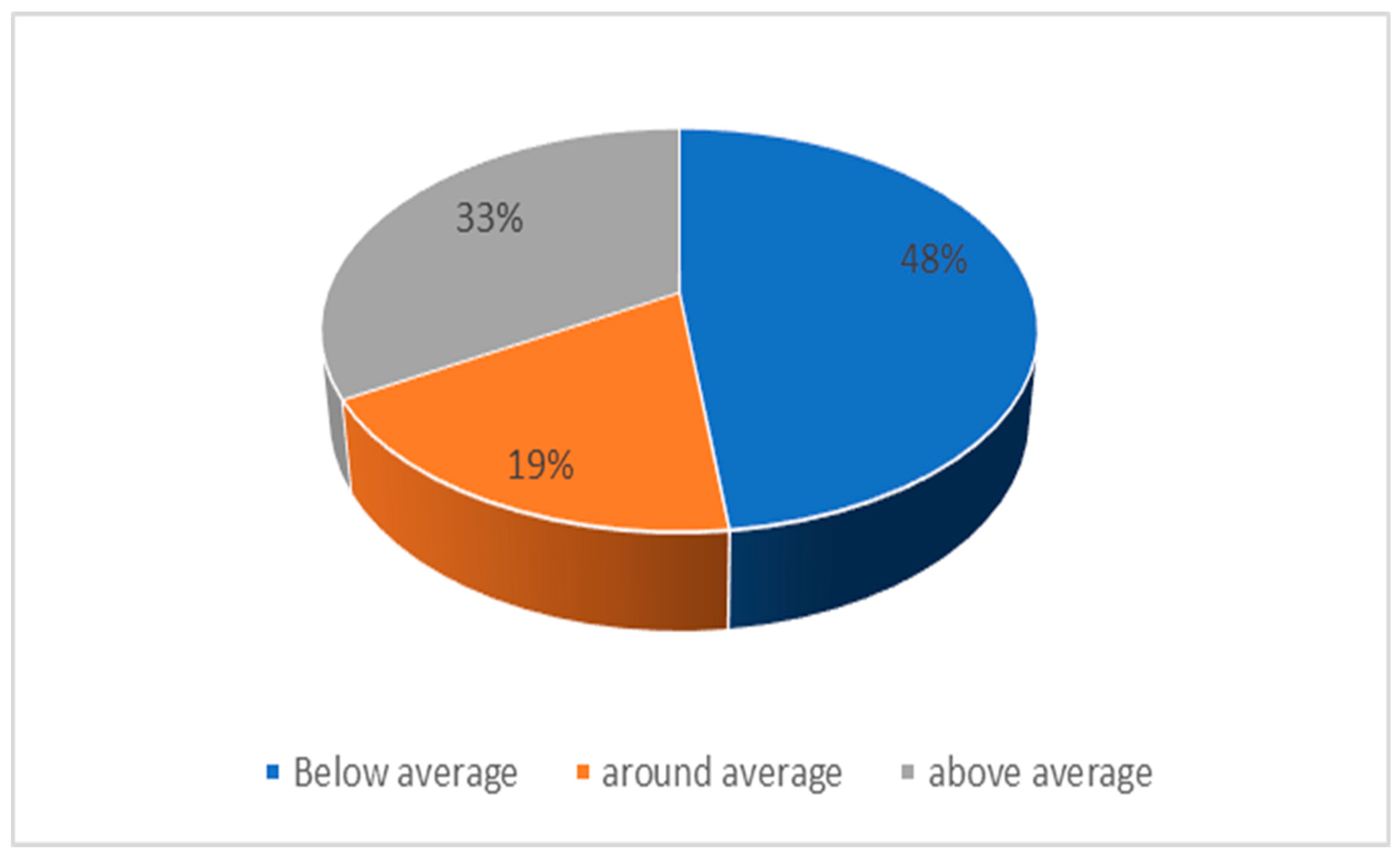

- in 19 countries, academic performance is below the EU average;

- in 7 countries, performance is around the EU average;

- in 14 countries, performance is above the EU average;

- in 3 countries in the Eurydice Network, and therefore the subject of our survey, no information was found in the OECD-PISA 2015 surveys.

- six cases the evaluation of the results is below the average;

- three countries (Finland, Norway and Switzerland) have largely positive results in academic performance and above average, despite the fact that in 2015 they did not have a formalized external evaluation system;

- no countries around average;

- three countries (Liechtstein, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia) where information is not available because these countries did not participate either in the Eurydice 2015 survey (although they belonged to the network) or the OECD-PISA tests (Figure 6).

- in three cases, the evaluation of the results was below the average;

- in one case, Switzerland has largely positive results in academic performance and above average, despite the fact that in 2015 they did not have a formalized internal evaluation system;

- in three cases (Liechtstein, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia) the information is not available because these countries did not participate in either the Eurydice 2015 survey (although they belonged to the network) or the OECD-PISA tests (Figure 7).

- we cannot consider only the outcomes of the students at a certain time, since this data are influenced by subjective and discretionary variables that can strongly condition the overall outcome of the test;

- we cannot use standardized tests, indistinctly administered, without considering the territorial, contextual, and social specificities.

5. Conclusions

- is a condition that defines the quality of the relationships between stakeholders and schools;

- reflects the ability to duly and adequately meet educational expectations and scientific advancement of the management;

- guarantees employment and contributes to the economic and social wellbeing of a country

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EU European Council. Presidency Conclusions; EU European Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- EU Council. Conclusions on Quality Assurance Supporting Education and Training; EU Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boeve-De-Pauw, J.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Cassano, R. School Governance, Accountability and Performance Management. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2017, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Gandini, G.; Franzoni, S.; Gennari, F. The role of key actors in school governance: An Italian evidence. UCER-A 2012, 2, 881–897. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.N.; Herrington, C.D. Accountability, Standards, and the Growing Achievement Gap: Lessons from the Past Half-Century. Am. J. Educ. 2006, 112, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camminatiello, I.; Paletta, A.; Speziale, M.T. The Effects of School-Based Management and Standards-Based Accountability on Student Achievement: Evidence from Pisa. EJASA 2012, 5, 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Link, S.; Woessmann, L. Does School Autonomy Makes Sense Everywhere? Panel Estimates from PISA. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 104, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Cassano, R. Improvement of management performance in the school system. In Proceedings of the 3rd Virtual Multidisciplinary Conference, Žilina, Slovakia, 7–11 December 2015; Volume 3, pp. 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, U. Governing the Education Sector. International Trends, Main Themes and Approaches, Institute for Educational Policy: Governance for Quality of Education. In Conferences Proceedings; The Open Society Institute & World Bank: Budapest, Hungary, 2001; Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A51767&dswid=6248 (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Daun, H.; Mundy, K. Educational Governance and Participation: Focus on Developing Countries; Report 120; Institute of International Education, Stockholm University: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Franzoni, S.; Gennari, F. School Networks and Sustainable Development. Symphonya 2013, 2, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollifroni, M. Environmental Sustainability and Social Responsibility: A theoretical proposal for an accounting evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference Accounting and Management Information System AMIS; Bucharest University of Economic Studies: Bucharest, Romania, 2011; Available online: http://riviste.paviauniversitypress.it/index.php/ea/article/view/1014 (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Cassano, R. Accountability e Stakeholder Relationship nelle Aziende Pubbliche (Accountability e Stakeholder Relationship in PA); Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerens, J.; Glas, C.; Thomas, S.M. Educational Evaluation, Assessment and Monitoring: A Systemic Approach. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=ROaWyYQtStYC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=Educational+Evaluation,+Assessment+and+Monitoring:+A+Systemic+Approach&ots=4mzpt9wJrO&sig=T0_NF2JYTzWNVerftbw7IaYlJuc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Educational%20Evaluation%2C%20Assessment%20and%20Monitoring%3A%20A%20Systemic%20Approach&f=false (accessed on 31 December 2018).

- Brown, M.; Mcnamara, G.; O’hara, J.; O’brien, S. Exploring the Changing Face of School Inspections. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 66, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerens, J. Effective Schooling: Research, Theory and Practice; Cassell: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tiscini, R.; Martiniello, L. Public Sector Reforms and the Role of Public Managers: The Culture of Performance and Merit. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, R. La Valutazione Come Strumento di Governo nel Sistema Scolastico; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salvioni, D.M. Corporate governance, management control and global competition. Symphonya 2005, 1, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Franzoni, S.; Cassano, R. Sustainability in the Higher Education System: An Opportunity to Improve Quality. Sustainability 2017, 9, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Cano, A. A Methodological Critique of the PISA Evaluations. Educ. Res. Asses. Eval. 2016, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, N.; Green, S.K.; Johnson, R.L.; Mitchell, M. Examining Teacher Ethical Dilemmas in Classroom Assessment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelucci, A. OECD-PISA. Il Punto. 2015. Available online: https://www.laletteraturaenoi.it (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Ravitch, D. The Dead and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining Education; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchiardi, P.; Torre, E.M. Valutazione della scuola e del sistema scolastico: Qualità formale e qualità effettiva (School Evaluation formal and real quality). Spazio Filosofico 2015, 1, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Utilization-Focused Evaluation; The New Century Text: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Steinbach, R.; Jantzi, D. School Leadership and Teachers’ Motivation to Implement Accountability Policies. Educ. Admin. Q. 2002, 38, 94–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ehren, C.M.M.; Altrichter, H.; McNamara, G.; O’Hara, J. Impact of school inspections on improvement of schools—Describing assumptions on causal mechanisms in six European countries. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2013, 25, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, R. Transparecny and Social Accountability in School Management. Symphonya 2017, 2, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M.; Potter, J.L. Integrating health impact assessment into the triple bottom line concept. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. Leadership and spirituality. Foresight 2006, 8, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughey, K.F.D.; Coleman, D.C. Adding another top and bottom line to Sustainability thinking in small to medium sized local authorities—Application to a small New Zealand local authority. In Proceedings of the 2007 ANZSEE Conference, Noosa Lakes, Austria, 3–6 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tjolle, V. Your Quadruple Bottom Line: Sustainable Tourism Opportunity. In Proceedings of the SMILE Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eurydice Network. Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe. Available online: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/assuring-quality-education-policies-and-approaches-school-evaluation-europe_en (accessed on 31 December 2018).

| External Evaluation | Internal Evaluation | Development Plan | Social Accountability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsible body | Responsible body | Responsible body | Available |

| Focus | Focus | Focus | Autonomy |

| Purpose | Purpose | Purpose | Disclosure |

| Frequency | Frequency | Frequency | Frequency |

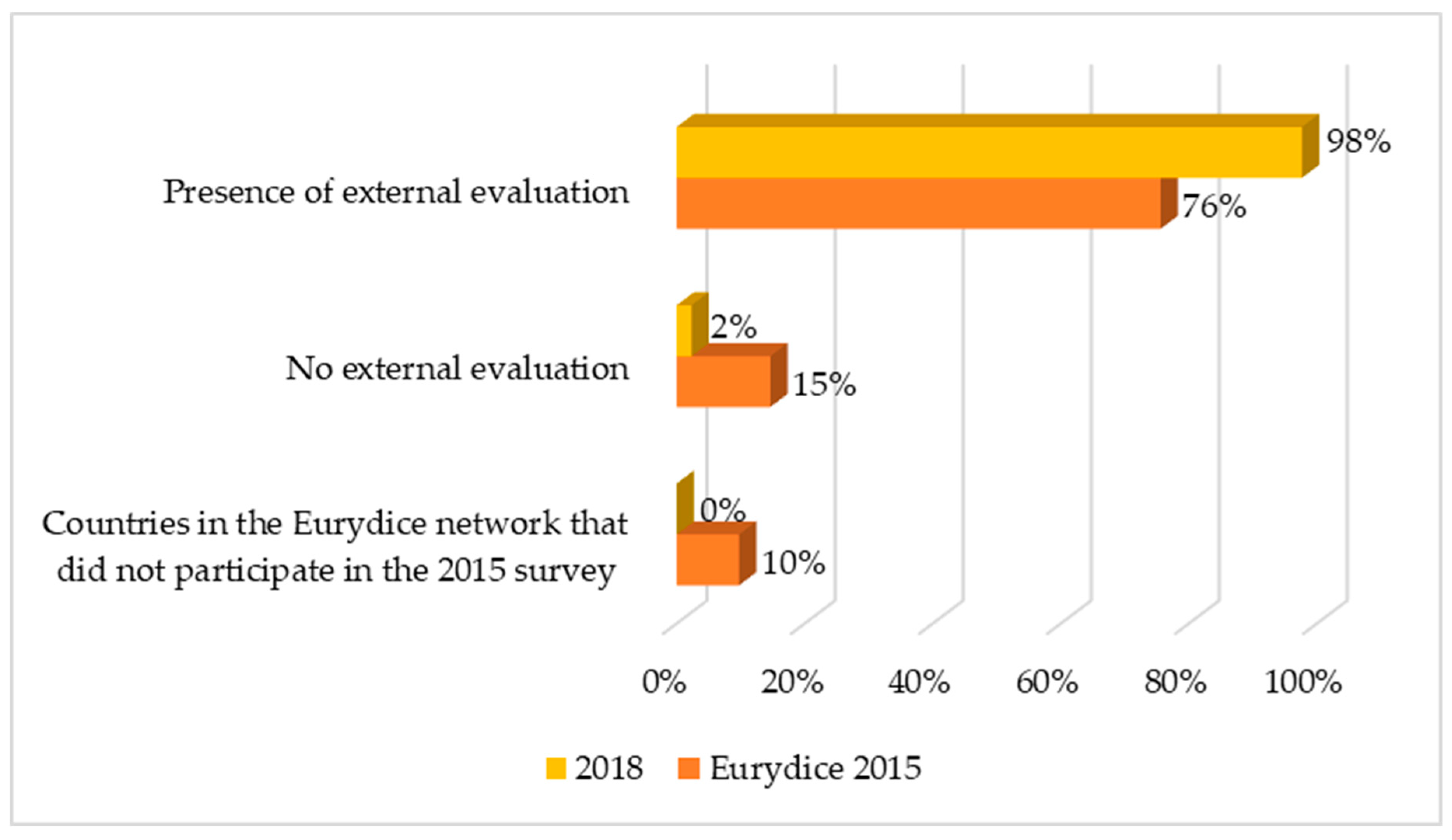

| External Evaluation of Schools | Eurydice 2015 Data Processing | 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.V. | % V. | A.V. | % V. | |

| Presence of external evaluation 1 | 31 | 76% | 42 | 98% |

| No external evaluation | 6 | 15% | 1 | 2% |

| Countries in the Eurydice Network not participating in the 2015 survey | 4 | 10% | - | - |

| TOTAL | 41 | 100% | 43 | 100% |

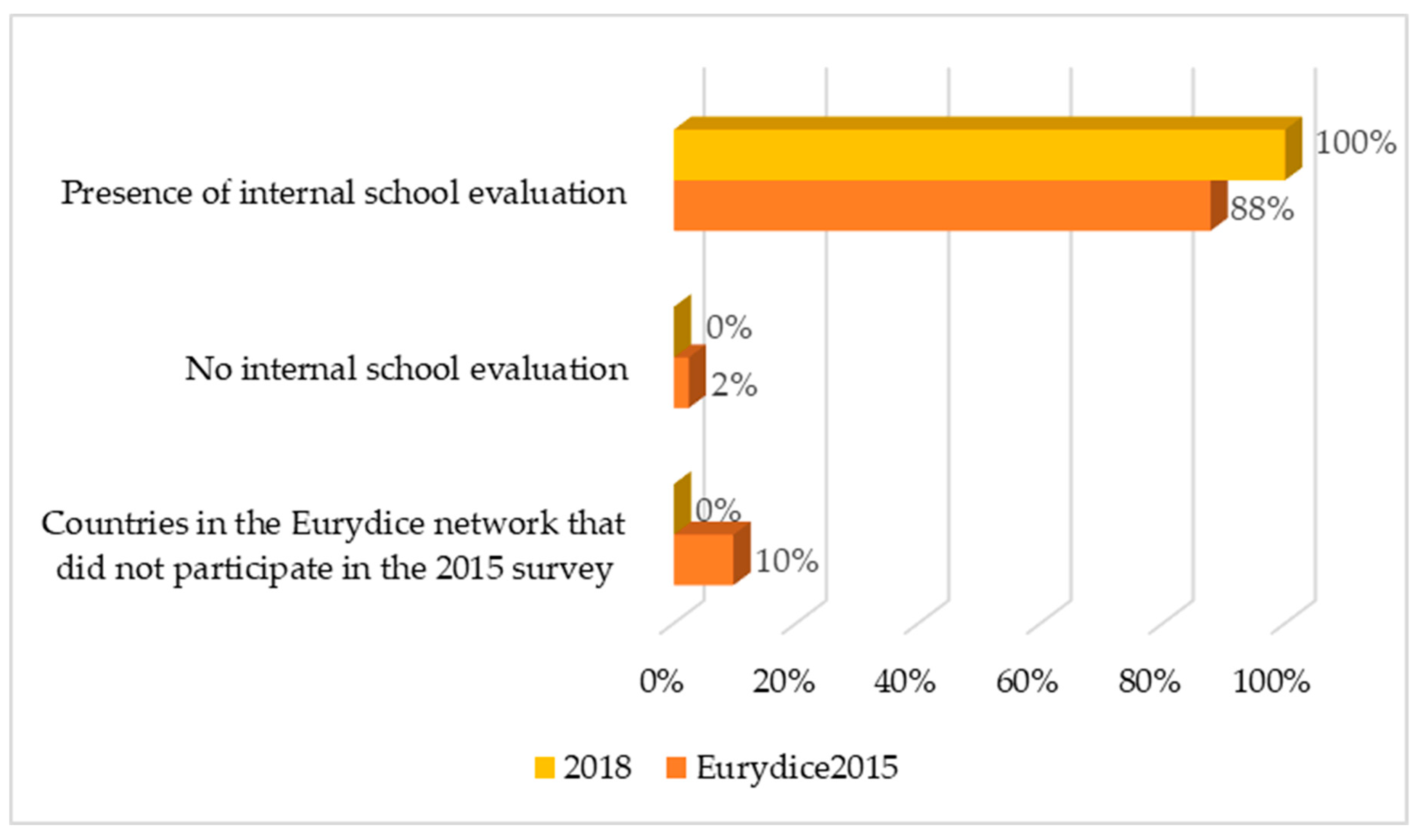

| Internal Evaluation of Schools | Eurydice 2015 Data Processing | 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.V. | % V. | A.V. | % V. | |

| Presence of internal school evaluation 1 | 36 | 88% | 43 | 100% |

| No internal school evaluation | 1 | 2% | 0 | 0% |

| Countries in the Eurydice Network that did not participate in the 2015 survey | 4 | 10% | - | - |

| TOTAL | 41 | 100% | 43 | 100% |

| Development Plan | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| A.V. | % V. | |

| Availability of statements on the use of the development plan | 34 | 79% |

| No statements on the use of the development plan | 9 | 21% |

| TOTAL | 43 | 100% |

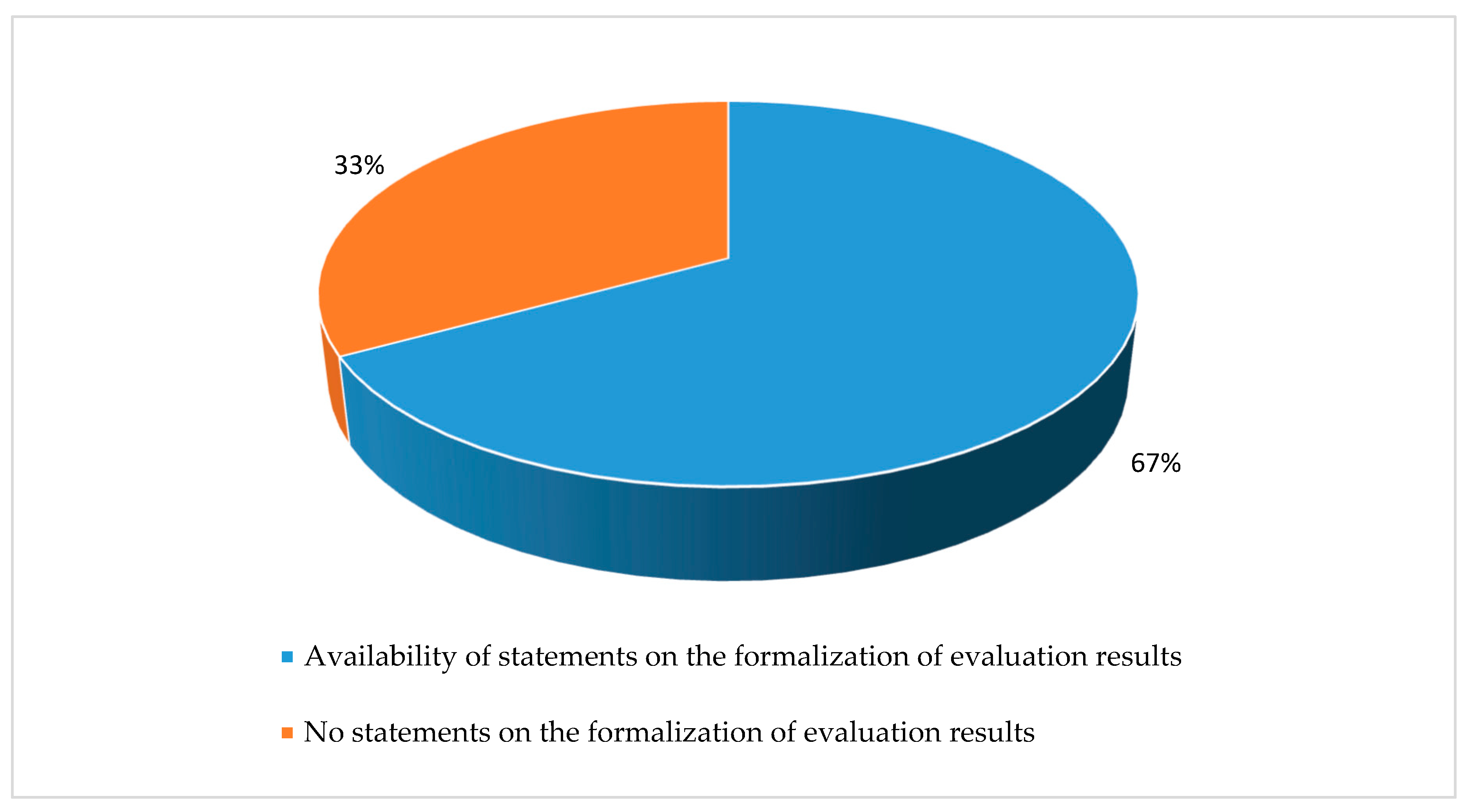

| Formalization of Evaluation Results | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| A.V. | % V. | |

| Availability of statements on the formalization of evaluation results | 29 | 67% |

| No statements on the formalization of evaluation results | 14 | 33% |

| TOTAL | 43 | 100% |

| Average Positioning | PISA 2015 Data Processing | |

|---|---|---|

| A.V. | % V. | |

| Below the EU average | 19 | 44% |

| Around the EU average | 7 | 16% |

| Above the EU average | 14 | 33% |

| Information not available | 3 | 7% |

| TOTAL | 43 | 100% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cassano, R.; Costa, V.; Fornasari, T. An Effective National Evaluation System of Schools for Sustainable Development: A Comparative European Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010195

Cassano R, Costa V, Fornasari T. An Effective National Evaluation System of Schools for Sustainable Development: A Comparative European Analysis. Sustainability. 2019; 11(1):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010195

Chicago/Turabian StyleCassano, Raffaella, Valentina Costa, and Tommaso Fornasari. 2019. "An Effective National Evaluation System of Schools for Sustainable Development: A Comparative European Analysis" Sustainability 11, no. 1: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010195

APA StyleCassano, R., Costa, V., & Fornasari, T. (2019). An Effective National Evaluation System of Schools for Sustainable Development: A Comparative European Analysis. Sustainability, 11(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010195