1. Introduction

The Mediterranean cities constitute a geographical space in which tourism represents a source of income for their economies.

We have taken the city of Malaga as a reference due to the regeneration process of the brand that is now under way. Malaga, as can be seen in

Figure 1, is a municipality and the capital of the Province of Malaga, in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, Spain. Malaga is the fifth most populated city in Spain. It is located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in a privileged spot. The city covers 398.25 square kilometers and has a population of almost 571,069 inhabitants, although almost a million people live in the metropolitan area.

As can be seen, tourism represents the leading sector in the economic context. Andalusia beat, in 2017, a tourist record reaching 29.5 million visitors, a historical figure that translates to a 4.7% increase with respect to the preceding year. The income earned in 2017 was also historical: 20,400 million euros, 4.5% more than the preceding year. With regard to the province of Malaga, 2017 was its best year ever in terms of tourism. It was consolidated as the fastest growing urban destination with a stay of over 1.3 million people, more than 2.4 million overnight stays, and an occupancy rate of 79% [

1].

Malaga brand was and still is the brand of the territory of Malaga. The Malaga territory brand includes the main elements that defines the territory of the province of Malaga: sun, beach, museums, Mediterranean diet, parties, friendly people, good weather, and traditions. In the sixties, when only the Malaga brand existed, other subsidiary brands appeared. One of them (The Coast of the Sun) positioned itself ahead of the Malaga brand. Why does Malaga need rebranding? The Coast of Sun brand is associated with the sun and the beach and if the institutions want Malaga to be a sustainable city in the future, rebranding is necessary. If institutions and local government want to avoid seasonality and offer other tourist services, they will have to return to the Malaga territory brand concept. Malaga, a city of contrasts, could not only be characterised by a sun and beach tourism. The city council is carrying out marketing campaigns of rebranding, but it is important to know if the new brand is being built on a stable structure. In short, it needs to be a brand that integrates everyone’s opinions.

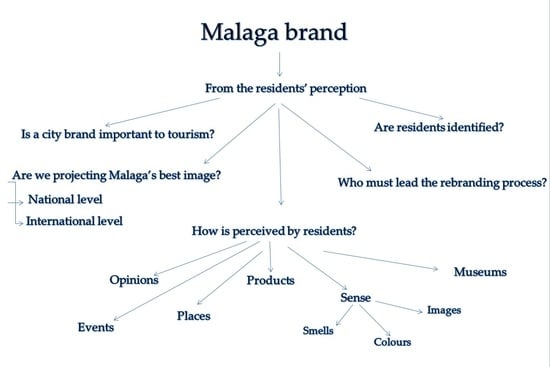

The objective of this research is to know if the new Malaga brand includes the perceptions of the residents. Currently, the rebranding process is focusing on Malaga as a culture city, a distant image of the old concept of Malaga as a city of sun and beaches. The cultural campaigns initiated by the Council of Malaga in order to market the destination in the winter months is focusing on museums. However, in the opinion of the residents, should culture be the basis of rebranding? For rebranding, we must take into account not only the external perception (tourist), but also the internal one (locals). If we create a new image of Malaga, we will make the destination sustainable. With regard to this research, the territory brand will be considered and hence the city brand as a set of differential elements of a geographical space.

The present paper addresses the city brand from the specific perspective of the residents of the city of Malaga. Until recently, this is the most forgotten aspect of branding studies although they can legitimize the city in a political sense [

2]. The typology of these studies offers great advantages, although they may fall into potential stereotypes. It is undeniable that this point of view offers a unique opportunity to represent the common history of the territory and it becomes a fundamental piece in branding strategies [

3].

In contrast to the perception offered by the visitors, the residents’ opinions are always a more complex picture and closer to the sense of identity [

4,

5]. These studies must be the ground on which to build, improve, and polish the existing brands or the brand structures of a territory, in a process called “rebranding” [

6,

7,

8,

9], applied to commercial brands or to cities [

10].

The definition of the territory brand would be the device that combines the differential elements of a territory. The identity in a competitive context appears as the recognition element in the cities’ positioning process. Territory brands imply a fundamental rebirth of the places from a construction process of the brand (branding) on which individual and collective identities are given value [

11]. The perceptions are used as basis for the construction of the experience of “identity”, so the elements that could form that identity and its relationship with those that, under the broad culture spectrum, offer exclusive advantages that make them different from others should be explored. The coexistence of several brands around a territory (city) determines the importance of rebranding [

10], in order to implement new strategies and objectives for city brands [

12].

Each territory can have different meanings depending on the people who are linked to it and it is important that these images are perceived individually and collectively and managed by institutions. They would be talking about construction policies and territorial image communication [

13]. The research should be based on an informed opinion and a deeper understanding of the city brand among residents. It will pave the way to formal and correct involvement of local governments in the review of an appropriate framework, which manages and modifies the attitudes that influence this public good [

14] (p. 362).

2. State of Art

The complexity of the territory brand and the reality on which it is projected is heterogeneous and diverse, according to Jiménez Morales and San Eugenio [

15] (p. 237). Some authors wonder if the territories brands are a necessity [

16]. Others recognize that brands offer the elements that help us differentiate ones from others. Thanks to this attribute we can market a destination and make it more competitive [

17].

The evolution and the sense of the territory brand leads to San Eugenio’s view [

18] (p. 197) in the era of the “branding of places”. That means strengthening the mark and its capacity for differencing territories.

It is necessary to take into account the city’s qualities or identifiable attributes, whether tangible or intangible. In this last chapter, there are a number of complex concepts, such as beliefs, attitudes, and experiences. We discuss the important elements that can contribute to the positioning of a brand in relation to the territory [

19,

20,

21].

In addition, it is precisely on that level where we can talk about the importance of the territories, in the sense in which these become speeches [

22], influencing both visitors and residents. In this way, we will descend from a territory brand to a city brand, with its concretion and proper management of the identity and the projected image being of vital importance.

According to Merrilees et al., [

14] the creation of a city brand should consider the perception of residents in a city, whose attitudes represent key elements, capable of affecting the consolidation of a city through its brand. This represents a new research line that allows the city to takes value and that is followed by a group of authors, whose studies deal with the relationship between residents and the own city brand [

2,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. All these authors lead us to consider the interest of analysing the perception of residents and the city brand applied to the Malaga brand. The most common indicators in the definition of the positioning of brand territory and consequently in the city brand will be identity, culture, heritage, traditions, and events, among others [

11], which are included in our research questions.

This article tries to determine if the marketing campaigns of the new Malaga branding are consistent with the residents’ perceptions. In order to answer this, we posed three research questions.

2.1. Brand and Identity

Users are exposed to image of places, symbols, and representations, with which they elaborate meanings, and with which a particular place can be identified. This is vital both for visitors and for residents [

4,

29].

The development process of the identity of a place begins in childhood and continues through time; therefore, this is a dynamic process and that associates the product of the interaction of memory with the awareness of certain values [

30]. The identity of the territories involves the research and the enhancement of their identity roots. This stage can be described as a contemporary, postmodern and global process. This underlines the economy of the identity, image, and symbolism [

11] (p. 207).

The rebranding process maximizes the benefits of the image that is projected. On a practical level, “Place Branding” relates the identity and the image of a space with the consumption experience of the place [

19]. A good image must be built and sustained, not invented [

8], hence the importance of citizen participation in its construction. The bonding between individuals and their environment is important [

31]. The citizen participation improves the sense of belonging to a place. This identification can contribute to the cooperation among organizations, clubs [

32], and to the union between the resident and his/her city.

The distinctive character of a place can identify the resident [

33] so that identification gains a fundamental relevance. The identification of the brand by the residents is a benefit for the city [

34] since it reinforces their own identity.

RQ1 Do the residents identify with the brand that represents their city?

RQ2 Do the residents know the brands that represent their city?

2.2. Brand and New Cultural Image

The promotion of culture is a greatest challenge in the design of campaigns to promote cities, in terms of the global economy [

35]. This offers new possibilities to cities that find in this element, a formula to make the promotion a success [

36]. If the residents identify themselves with their city and the institutions do respect their opinions, the city may offer activities related to the culture that promote the image of the city and, at the same time, achieve a climate of attraction for tourists, new residents, or investors [

28].

The city brand is used for projecting an image in the world and has become a very powerful asset with which to promote tourism., It may also affect citizens’ quality of life [

37], generating new business opportunities, claiming the identity of its territory, and, consequently, highlighting its market share [

38] (p. 157), [

39].

The culture significance and entertainment activities in general favour the construction of a destination [

40] and specifically, the culture becomes a way to authenticate destinations [

19] not only for visitors, but also for residents. The role of culture and residents’ perception of other Mediterranean cities, such as Barcelona [

41], can create leverage to successfully address the theme in other places, as this kind of study are still scarce for Spanish speakers [

3]. Culture is so important for the brand of the city that is used as a strategy for the economic, social, and environmental renewal of the cities, being one of the strategies that improves the competitiveness of destinations [

42,

43].

RQ3 Do the residents perceive the new image of Malaga as a cultural city?

RQ4 Do the residents think that the new brand is built on the correct elements?

2.3. Brand and Events

The city brand is defined as the bridge between the real and objective space and its perception; these differences may be key and the great events may, when they are created by an organization, modify the attitude towards brands [

44]. Through experiences, the city brand can be improved and consolidated. When the event fulfils the requirements and it becomes significant, it will improve the attitude of visitors and residents towards the city brand [

14].

The inherent symbolism to the city is channeled through the brand, which is consolidated as an important intangible asset of the city, on which the majority of the urban and/or metropolitan communication processes are based [

11] (p. 204). Big events or those that have a great projection, can become generators of emotions of satisfaction [

45], impacting the city brand.

The differential characteristics of marketing of events exhibited by Vila Lopez et al. [

46] (p. 195), following [

47] show, from the offering side, the capacity of a destination to attract visitors, but it also makes them a better place to live from the perspective of the residents themselves.

The type of events that take part in the development of experiential marketing is very diverse [

48,

49,

50]. There are few examples of studies focusing on residents’ perceptions for “mega-events” [

51,

52]. However, the review of the literature has revealed that the numbers of brand studies from the residents’ perspective are increasing [

53,

54]. In addition, the relations that are created between the event and the image that is projected from the city can reveal the importance of the affective and symbolic components, in the transfer process between the perceptions of the sponsored activity and the brand [

55].

In sum, these studies show a relationship between emotional experiences and attitude towards the brand, as confirmed by Vila Lopez, et al. [

46] (p. 197), considering that the Malaga brand has repercussions on events due to their capacity to promote tourism and to modify the attitude of the residents towards the same city brand.

In this framework, in the interest of the events and the repercussions that they may have on the city brand, the following research questions have been raised:

RQ5 Do the emotional experiences lived through the events modify the residents’ attitude towards the city brand?

RQ6 What are the events that can represent the city?

3. Methodology

The aim of the survey was to measure the residents’ perception about the Malaga brand. The quantitative opinion survey was used as a study method in order to answer the questions that were raised in this research. A pilot study of the questionnaire was conducted to ensure suitability, clarity, and relevance of the research instrument. There were no substantial changes after it. The final survey was translated into the three most important languages in the city of Malaga, Spanish, English, and German. Respondents were selected by the snowball sampling strategy [

56]. McMillan and Schumacher [

57] indicate that this technique is defined as the application of a standardized procedure to gather information from a large sample of subjects who meet the desired characteristics for our research.

Snowball sampling can happen in a number of ways. The questionnaire was sent to potential participants, recruiting them for the study. In the first step, the authors sent it to young people, students of different ages, workers, unemployed individuals, housewives, and professionals. Then, those participants recommended additional participants, and so on, thus building up like a snowball rolling down a hill. This procedure may show certain deficiencies (Non-random, anchoring, and lack of control over sampling method) [

58]. However, as pointed out by San Eugenio [

41], Brickman Bhutta [

59], and Unkelos Shpigel, et al., [

60], it is possible to locate hidden or specific populations, and among other advantages, it could be useful as complementary methodology in order to boost the quality of the research.

The snowball sampling formula with online application involves sending the questionnaire via social networks such as Facebook [

61,

62], LinkedIn [

51], mail, and Whatsapp. It allows us to gain information through a fast, cheap, and efficient process [

63]. The internet makes possible to conduct survey research faster than ever before. In economic terms, this useful way is considerably cheaper than other methods, taking into account the time and the tools. On the other hand, Baltar and Brunet [

64] consider that the virtual response rate is higher when using social networks than with the traditional snowball technique. According to the list of companies in the city, the invitation has been sent through their Facebook profiles, which means that businesspersons from the province can also see their opinion expressed in the survey. In an exponential way, Whatsapp has been used to reach a whole network of individuals of different ages and professional economic conditions through family members, representative of the reality of the city of Malaga. We conducted the analyses and graphs using IBM ISPSS software.

Sampling

Data collection was performed during the period between 15 May 2018 and 15 July 2018. After collecting and debugging the information, 1106 valid questionnaires were validated. An error of 2.1% for a confidence level of 95% was obtained (p = q = 0.5). In our study, sampling is reflected in

Table 1.

The study made use of a questionnaire as the research instrument. The final structured questionnaire was prepared using mainly close-ended questions. In an investigation related to the perception of the Malaga brand, it was necessary to carry out a review of the literature, which allowed us to select the adequate items. For studying the demographic profiles of the respondents, questions with multiple choices were framed in the study. The survey was divided into two sections. The first one was profiled to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of the population. The respondents were asked about their gender, age, nationality, level of studies, work activity, income level, and about the number of years that they had been living in Malaga.

In the second section, we focus on the fundamental aspects for the research; the questions related to the residents’ perception of the Malaga brand. In this part, there are 24 questions of which 9 were answered through a Likert scale of 7 points, specifying the level of interest, importance, or significance of the issues raised, where ‘1’, indicates Not at all importance or Strongly disagree and ‘7’ Extremely important or Strongly agree.

Issues are related to the identity and identification of the city brand, its management, the degree of economic interest for companies, its geographic capacity, that is, whether the brand affects the entire province or only the city.

The search for the reconstruction of the Malaga brand (rebranding) has led to intense analysis and debate considering its importance and seeking the perception of the products or services with which it should be associated. It is also important to keep in mind that the brand has to give an adequate image not only in the local sphere but also at national and international level. The choice of the elements (places, smells, images, events, and sounds) that best represent Malaga and the cultural elements that identify it are issues of great interest. In this sense, we have tried to take into account which words identify the Malaga brand and what are the products or services associated with it.

A series of questions related to the perceptions that the residents have of the events that take place in the city are addressed here. These are “emblematic” celebrations, such as Holy Week, The Fair, and The Film Festival, among others. The objective is to know the degree of satisfaction of the residents because sometimes these events cause massive tourism in some urban areas of the city. Finally, the questionnaire reflects on the brand and the senses. In order to build, manage, and position a brand, it must incorporate elements that activate the senses. The consumer will not only identify it by its excellence, but also generate sensations and emotional memories that can be connected with the brand.

4. Results

A total of 1106 subjects participated in this survey. Regarding the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, there were 530 women and 576 men. The distribution of age groups is representative, although a high response rate was given by people over 56 years old (49.7%). The majority of participants were Spanish nationals (96.6%). Regarding the level of education, 65.2% of subjects had university or postgraduate qualifications, and 1.20% of the informants had primary qualifications. The distribution by activity is quite dispersed. Retirees were the largest group in terms of occupation (26.1%), while 32.9% had individual incomes between 25,001 to 40,000 euros per year.

We thought it was important to know if the residents had been living in Malaga for a long time in order to know if there is a relation between the identification and the years of residence. To the question: How many years have you been living in Malaga? they answered “all of life” 59.6% and 22.4% “more than 20 years”. In this sense, there is no correlation between identification with the brand and years of residence. Pearson’s test was applied and the result shows that

r was equal to 0, meaning no linear correlation. The Malaga brand is perceived as valid for the province by 67.8% while 32.2% of respondents feel that it only represents the city and not to the rest of the municipalities. Responding to the first question of the second section, the participants were asked about the identification with the present Malaga brand. As can be observed in

Table 2, women identified with the brand more than men did, but it is important to note that 44.2% of respondents did not identify with the present Malaga brand.

Residents identified with the new culture brand but consider that the Malaga territory brand is not well managed (61.7%). In a Likert scale, the responses to ‘Malaga territory brand is well managed’ are concentrated between ‘1’ and ‘3’ (Strongly disagree, disagree, and somewhat disagree).

In addition, it is important to bear in mind what residents consider about the benefits of the brand. They perceive that the territory brand brings benefits since most of the answers to ‘A territory brand provides benefits to the business fabric’ are placed in the best sections of the Likert scale. Specifically, 69.4% of the interviewees give a rating between ‘5’ and ‘7’ (Somewhat agree, agree, and strongly agree). On the question of who should be responsible for rebranding and for implementing the necessary changes, the respondents are in complete agreement. The Council of Malaga received the highest percentage (69.8%), well ahead of the Malaga Provincial Council with 16.6%.

The survey also asked a question to know if the residents know the brands that already exist in the province. In this sense, it was possible to verify whether the most well-known brands are related to different elements and values. The main ones are those indicated below.

1.—Coast of the Sun (32.5%)

The aim of this brand is to promote the coastline in the province of Malaga. There are many tourist services of all types, including berths for sporting boats at 13 marinas and yacht clubs, as well as golf courses, all types of sports facilities, casinos, and a myriad of leisure and entertainment options.

2.—Malaga Flavour (20.3%)

The first major objective of this brand is to unify the highest quality products in the province under a global image. The second objective is to promote the commercialization of all products linked to the brand, highlighting the quality and uniqueness of each of them.

3.—Malaga Great City (19.5%)

The objective is to promote the tourism supply, events, temporary exhibitions, and museums.

In relation to the importance for promoting Malaga as a destination, the residents consider the brand “Malaga Flavour” (32.5%) firstly, followed by “Malaga Great City” (20.3%) and “Malaga The Coast of the Sun” (19.5%). The study also shows the preponderance that exists in the perception of residents about the Costa del Sol brand in comparison with the Malaga brand. In fact, the participants consider that the first one is still the most important (543 responses between the scores of ‘6’ and ‘7’.) The truth is that the latter includes the former.

Regarding Malaga’s image at national and international levels, the residents were satisfied. The ratings between ‘5’ and ‘7’ reached 76.4% and 55.4%, respectively.

The question about the kind of products/services that should be associated with the Malaga brand allowed us to observe, from the resident’s opinion, the list headed by the culture and cruise sector (317 and 301 respectively). As can be seen in

Figure 2, other outstanding elements are leisure and the agroalimentary sector (products with designation of origin), chosen by 77 and 151 participants, respectively.

Participants were asked about the words that identify the Malaga Brand. As can be seen in

Table 3,

Espetos (skewer of sardines), Sea, and

Biznagas (bishop’s weed) received 260, 259, and 243 respectively.

As can be seen in the

Figure 3, when asked about the cultural elements that identify the Malaga brand, indicating a maximum of three responses, the most representative would be the Picasso Museum and Birth House, followed by the Roman Theatre and Arab Military Fort with 227, 183, and 142 informants, respectively. These are followed by Carmen Thyssen Museum and Cervantes Theatre.

In relation to the traditional events, as can be seen in

Table 4, Holy Week is the most highly valued, followed by the Film Festival. Holy Week was considered to have the biggest contribution to the Malaga brand. However, the Carnival of Malaga, a tradition that has been interrupted in the last century, had lower impact.

The newest events of the city are Christmas Lights, White Night, and Malaga Film Festival. If we take into account the maximum impact on the brand (Likert scale ‘7’), the results vary from 26.2%, 8.4%, and 36.6% respectively, making the Film Festival one of the events with the greatest impact on the brand.

The study of the senses has come to offer very significant nuances, regarding the colours, smells, sounds, and places associated with the Malaga brand, as well as the image that best represents them, allowing in this case a maximum of three responses.

Regarding colours (

Table 5), the most recognized were green and purple (the colour of the Malaga flag), by 288 and 294 respondents, followed by the range of blues; the lightest, representative of the sky and sea was chosen by 251 interviewees and 135 opted for the dark blue.

Regarding the smells (

Table 6), the

Biznaga, known in English as bishop’s weed, is the element that best represents the Malaga brand; specifically, it was mentioned by 55.9% of the respondents, followed by the

Espetos (skewer of sardines) and sea saltpeter, with similar percentages of 18.4% and 17.4%, respectively.

Regarding sounds (

Table 7), they associate the Malaga brand with the sound of the sea (42.3%), the

Verdiales (party music and local dances, 40.1%), and finally with the bells of the cathedral (10.8%).

The places that best capture the spirit of the city are, in the opinion of the residents of Malaga: the Larios Street, the Cathedral, the Port of Malaga, the Alcazaba (Arab military forts), and La Farola (the lighthouse) with 307, 270, 204, 195, and 130 mentions, respectively.

5. Discussion

The brand from the residents’ point of view should be improved inside and outside the city. This is reflected in the low percentage of identification with the Malaga brand (55.8%) in comparison with not identified (44.2%). There is a high percentage of responses indicating that the institutions must implement changes in the promotion of the destination. In response to the second research question, the residents of Malaga know many brands, but the most important, the Malaga brand, was not chosen by any participant. This datum is very relevant when the current target is to place value on the Malaga brand.

Responding to the third and fourth research questions, the new cultural image of the city is being perceived by the residents. This means that there must have been a change. In relation to the elements associated with culture, it can be seen that not all of them are museums. The study shows that the residents take into account a wide range of elements, which have been forgotten by institutions. This is evident when we compare residents’ and the Malaga City Council’s perceived images of Malaga.

In relation to the events, the residents agree with the stakeholders’ strategy. The Holy Week is the top-rated event. This traditional event has a major economic impact on the territory.

If we pay attention to the study of the senses, residents provide very important assessments. While the Malaga City Council chooses the colour blue for the marketing campaigns, the residents choose purple and green. We must emphasize that these two colours are those of the flag of the city.

Responding to the two final research questions, residents who reported having taken part in the event gave it a high level of impact on the brand. Therefore, we understand that the emotional experience lived through the events modifies the attitude of the residents and affects the city brand, with the Holy Week having the greatest impact and the Carnival having the lowest impact on the Malaga brand.

Concerning the specific question regarding smells, the Biznaga is the element that best represents the Malaga brand. It is important to note that this flower does not appear in the announcements of the city.

The sounds are also an important part of this study. The sound of the sea and the Verdiales, the music of the typical dances of the city, are the sounds with the greatest frequency in the responses of the participants.

The main street of the city, Larios Street, is the place that best captures the spirit of the city, followed by the cathedral, known as La Manquita because it is an unfinished building, and Muelle Uno (the port).

Finally, this study reveals that the residents of Malaga identify the Malaga brand with a cultural coastal city. According to residents, Malaga has the scent of the Bizganas and the sea. Malaga is a city painted in green, purple, and blue where visitors can hear Verdiales and the sound of the waves. It is a place that loves Picasso and has his paintings as a cultural reference. A city that, in spite of having one of the most famous museums of the world, the Pompidu Centre, values first the birthplace of a painter. It is a place in the Mediterranean where traditional events such as Easter Week coexist with new ones such as the Malaga Film Festival.

6. Conclusions

The current tourism model has been called into question from various points of view. It has both positive and negative effects, which, once analysed, need to be renewed, taking into account the necessities of the tourists and residents. The fact of the seasonal nature of the tourist sector is a problem for many coastal cities.

Economic growth in Spain has been sensitive to persistent expansion of international tourism. This growth is the main interest for institutions, but in the case of Malaga, another problem of touristification could happen in the near future. Another topic could be the competition among destinations. Tourism accounts for a high percentage of Spain’s economic output and the number of foreign visitors rose to eighty-two million last year. Therefore, Spain is the world’s second most visited country after France. Malaga has benefitted from the military attacks and other political problems in Turkey, Tunisia, and Egypt but they are experiencing a resurgence, marking a revival of demand for these destinations. This may present a risk for Malaga since the growth rates will start to slow down over the next year. That is why the brand is extremely important. Institutions are not looking for a happy coexistence between tourists and residents at this time. The Government wants to increase the number of tourists, the spending per tourist, and the percentage of tourism-generated revenue.

The city of Malaga has evolved from sun and beach tourism to a new model of a cultural city. Malaga is undergoing major transformations in regards to its infrastructure. New museums, the rehabilitation of the historical centre, and a change of mentality are the fundamental factors in the new image of the city. Malaga is now a modern and vibrant city with long multicultural traditions, an active city that does not depend only on the climate and the sea. The objective of reforming the brand is not simply to do better than before, but to do better than elsewhere. The rebranding process in this case is understood as a tool that takes advantage of a coherent and positive image, which serves as the engine to improve the perceptions of the public and contributes to improving its competitive capacity. Malaga offers a wide selection of services for all types of visitors and pockets.

From an economic point of view, without an attractive and distinctive brand, a tourist destination cannot achieve high future value, profitability, and loyalty of its visitors. The brand is competitiveness. For the Malaga City Council, the brand is understood as a step towards promoting economic benefit. The image and the brand are associated with the perceptions of the city and they have the capacity to influence investment offerings, political and diplomatic relations with other cities, possible visitors, etc.

The coexistence of several brands around a territory determines the need to start a rebranding process. This research has contributed with elements and proposals that will lead to the successful introduction of an improved base on which a new global brand can be built. We consider that this study should be drawn up to give a clearer picture about the identification between the residents and the Malaga brand. In this sense, the answers could be useful for institutions. Traditional studies in Malaga have not included the internal viewpoint of residents. Therefore, it is extremely important to progress towards better coordination between institutions and the local people.

In the city, there is a variety of brands which many residents support. In this case, there is a need to merge them into the same idea. Each brand must enhance or value different elements of the city but all must be under the same concept. The coexistence of several brands within the same territory determines whether it is necessary to carry out a rebranding process. There must be synergy between public institutions in order to focus on the rebranding process. This could be a problem if the brands are not well managed. Due to this, it would be interesting to study what the existing brands’ projected images are and how to improve them. In this research, we investigated how the residents perceive the city and then compared the findings with the Malaga City Hall campaigns.

In this sense, we can find many differences between what residents think and what the institution thinks. The resident has several roles. On the one hand, the resident can help with the choice of the attributes that define the image and therefore help the brand. The residents are the best ambassadors of their city, so it is very important that they identify with it. In short, the citizen lives every day with the city and with the visitors. We can affirm that the campaigns that promote Malaga as a destination use an image of Malaga that does not resemble the image perceived by the residents. While Malaga City Council focuses its efforts on promoting the new Pompidou Center, residents consider Picasso’s Birthplace as the museum that best represents the Malaga brand. The results reflect that there are two big issues in relation to the brand. On the one hand, the perception of the residents has not been taken into account in the rebranding process and, on the other hand, the brands are not focused on the same objective. What happens when the brands are in competition with each other? If the objective is to recover the Malaga brand and its attributes, we cannot continue to promote others ahead of it. We must remember that the Malaga brand includes The Coast of the Sun, Malaga Flavor, Malaga Great City, and Malaga Smart City, among others.

Before a rebranding process, it is necessary to know what the most important elements are, what our identity is, what our needs are, what our destination needs, and what our values are. Then, the City Council must study each brand to promote them in a correct way.

Despite this, the projection of the Malaga brand should continue to develop. In this sense, the high percentage of responses in favour of the image at national level is countered by the perception obtained at the international level. Therefore, as we said before, institutions, companies, citizens, and tourists should continue together to improve the image in order to get better results. The new image of the city of Malaga must be projected in relation to the culture. All of these famous elements must be taken into account. This is one of the ambitious wishes of the institutions, so it is relevant for our research to formulate research questions in this regard. It also allows us to verify if the residents perceive the new image of Malaga as a cultural city.

Seasonality is still present in the city of Malaga. If we want to have a sustainable destination, we need to distribute tourism throughout all the months of the year. This is not possible if the promotional campaigns only talk about the beaches. Malaga has a wide range of cultural and leisure offerings; however, institutions continue to promote the climate. This would not be a poor policy if the city could show all its attributes. Malaga is not a city with new monuments. Brands differentiate between destinations but if Malaga offers the same brand as other places it will not be special. In that case, Malaga will not compete in culture, tradition, events, or Mediterranean diet, then, Malaga will only compete on price.

So, while the destinations are competing, we must present a robust brand that can not only attract tourists at all times of the year, but also continue to grow economically and facilitate coexistence.