Abstract

The objective of this study was to use the perceptions of internet users to analyse the effect of the social, economic and environmental dimensions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) implemented by hotel establishments in order to determine whether those dimensions are perceived by consumers. Our analysis was based on a sample, distributed by age, sex and province segments, obtained from the Andalusian population between 16 and 74 years of age who are users of travel websites (e.g., TripAdvisor, Booking) and hotels corporate websites. A questionnaire was used to investigate each latent factor related to the three main dimensions of CSR that may affect the perceptions of accommodation service consumers. The questionnaire was statistically validated and developed in previous economic studies in this field. The data were analysed using Partial Last Square (PLS) methodology. The results confirm the validity of the three dimensions analysed, although consumers appear to play more relevance upon economic and environmental factors than upon the social components of CSR.

1. Introduction

The starting point for the modern analysis of CSR in the scientific literature was the publication in 1953 of Howard Bowen’s book Social Responsibilities of the Businessman [1]. Bowen provided a new paradigm for obtaining business results that took into account the benefits to the community in which the company was based, but he did not provide a definition of the concept. Since Bowen, several institutions and firms have tried to define it, but no uniform definition of CSR exists to date [2].

Among these public institutions, and in relation to the geographic and social environment in which our analysis is framed, the European Commission has indicated the way forward for companies by noting that they must fully assume their social responsibilities and, in line with their network of relationships, they must establish a process designed to integrate social, environmental and ethical concerns into their business operations. For the European Commission, this triple field of action (i.e. social, environmental, and ethical) forms the basis for companies and institutions to take action. Following the EC suggestions, some European countries (e.g., Italy) have introduced ethical dimensions in some sectors into their legal systems [3].

However, from the companies’ point of view, the economical dimension is more important than the ethical one; the basis of the CSR used to be the social, environmental and economical dimension. In this sense, the Financial Times defines CSR as “a business approach that contributes to sustainable development by delivering economic, social and environmental benefits for all stakeholders”.

Traditionally, companies have been considered as having a negative effect on all three aspects, particularly the environment, but now they are expected to have a positive effect. Consumers expect this from large companies, but also from smaller ones. We must not forget that most companies that operate in the tourism sector are small or medium sized (more than 90% for the Spanish case) and, as [4] pointed out, those firms need to implement strategies and take choices to overcome the limitations faced by small firms.

It is mainly through concern for the environment that the concept of CSR has been incorporated into the tourism industry in general. The hotel industry is relevant not only because of the revenues and employment that it generates worldwide, but also because it produces high levels of carbon dioxide emissions, is highly dependent on energy, and can have a marked effect on natural resources. The implementation of CSR in the Spanish tourism industry has been uneven, because of the types of companies that have begun to introduce it and because of the type of practices that have been implemented [5].

Such diversity in the implementation of CSR is due to the nature of the tourism product itself and to the supply-demand relationship that exists in this sector.

From a market point of view, customers and suppliers have different perceptions of the same reality. Clients tend to see the tourism product (i.e. transport, accommodation, catering, and activities) as a complete package that provides them with a satisfactory experience for which they would pay an all-inclusive price. However, tourist package suppliers tend to think of the product as singular: that is, hotels offer accommodation but have no influence on the rest of the package. In other words, the client has a vision of the tourism product as a "destination package", whereas each individual supplier typically implements CSR in isolation [6].

Furthermore, the buying/selling process has the characteristic of the product being consumed at some distance from the client’s home. That is, the client buys the package before traveling to the destination without being able to test the product before consuming it. This characteristic underlies two relevant aspects in our analysis: consumer trust during the purchasing process, and the purchasing channel and its recent evolution. As CSR has grown in relevance, new technologies have also drastically changed the way consumer-tourists behave when obtaining information, choosing a product and undertaking the purchasing process using the new technologies that expand the number of products available. The relentless development of electronic commerce (e-commerce) has had a strong effect on the tourism industry because it has given rise to a new consumer profile. This consumer is highly sensitive to key CSR issues and also has more tools to demand that tourism companies implement CSR. As [6,7] pointed out, in countries with advanced social development, buyers consider the CSR factor as part of the purchasing decision process that is also valued by the consumer, allowing companies to charge extra for the same product.

Although in the tourism sector, as will be discussed in Section 2, studies that have considered the environmental variable of the CSR have been very frequent, recent changes in consumer demands regarding the environmental impact have not been taken into account. In addition, the rapid growth of the hotel industry has also had negative aspects [8]. In this context, and as noted in [9], consumers also take into account the precarious employment situation, as well as working conditions and salary in many jobs, in the hotel industry. A greater social awareness of women’s rights and their imbalances in terms of wages and employment opportunities have placed this sector, composed mostly of women, into spotlight. The case of cleaning workers and floor services in Spanish hotels has also been analysed from the point of view of tourism consumer decisions [9].

The aim of this study was to use the perceptions of internet users to analyse the effect of the key dimensions of CSR implemented by hotel establishments. Specifically, by using a database that contains references to the behaviour of e-commerce of these consumers, we can determine the impact on their purchases of accommodation due the way they perceive the efforts of hotel companies in terms of respect for the environment, social integration and economic sustainability. The study was based on a sample selected for the case of Spain.

2. Literature Review

The literature on CSR in the hotel industry is scarcer than that for other fields of analysis within the tourism sector, and it is even scarcer when compared to other economic sectors. As Gligor-Cimpoieru et al. [10] pointed out, most studies in this field are limited to environmental issues, and tend to neglect the social and cultural variables of CSR. Thus, it has often been pointed out that tourism makes intensive use of the environment, which is a de facto indispensable element in the tourism product [5,11,12,13]. Although this view is generally true, not all tourism activities or all tourism segments have such a direct relationship with the environment. For example, holiday hotels are typically located on coasts or in natural areas where the environment is an intrinsic part of the tourism package. Thus, they have to implement specific environmental management measures. However, city hotels mainly cater to business tourists, and are therefore more concerned with the management of human resources and occupational health than with environmental management [14].

However, most large hotel chains have focussed the development of CSR practices on the environmental dimension and have reached higher levels of sustainability. Their objectives are to obtain cost savings and increase their presence in the new market segments that are more demanding regarding environmental issues [6,15,16,17,18,19]. In performing an analysis of CSR in Spanish hotel chains, [5] did an in-depth analysis of the literature and found that most studies have addressed the types of CSR practices implemented in hotel companies, the publication of CSR reports, and the economic effect of CSR. The latter aspect has been widely analysed by other authors [20,21,22,23]. Some of these authors have suggested that increased CSR investment leads to short-term improvements (i.e. increased profitability) and long-term improvements (i.e. increased company value). Therefore, investment in CSR benefits the organization ([24,25]) by improving its competitiveness and performance [17]. It also improves employee commitment, motivation, and loyalty to the company ([26,27,28]). It has also been suggested that clients are willing to paying more for sustainable measures [29]. Other authors have suggested that the change in hotel management has been driven and will continue to be driven by the demand from customers who currently show greater concern for the cultural and natural heritage, and by the increase in environmental protection and ecotourism practices ([30,31]).

In relation to the size of the company, in the literature, it seems that only large hotel companies adopt proactive policies in terms of CSR. However, some authors such as [32], taking Eurobarometer data, point out that small hotel companies which consider environmental concerns to be among their objectives have a greater increase in sales and go beyond environmental legislation. To the best of our knowledge, nobody has done this type of study for the Andalusian hotel industry. However, we could take as a proxy the work of [33], who has analysed the environmental strategy and performance in small companies in the Andalusian automotive sector, concluding that these firms vary their environmental compromise from reactive regulatory compliance to proactive prevention of pollution and environmental leadership, the latter being those that obtain the highest economic performance.

Not everything that glitters in CSR is gold, and some authors who have published articles on the lodging sector have expressed doubts concerning the concept or even whether CSR actually exists, at least for accommodation companies. Thus, [34] criticised the marked confusion regarding the concept of CSR and sustainability in the business world. Some authors as [35] suggested that CSR is nothing more than a way by which to gain a competitive advantage in the market. Others, such as [36], have suggested that the prevailing approaches to CSR are so fragmented and disconnected from business and strategy that they mask great opportunities for companies to benefit society.

Regarding the demand side, there is little research on what sustainability means to consumers, which aspects are most valued, and what they would most like to change regarding company behaviour ([35,37]). Some authors have suggested that from the perspective of consumers, CSR has only two dimensions: society and the environment [38].

Several studies conducted in Spain, and specifically in Andalusia, have shown that environmental quality standards, such as ISO 14001, help improve hotel productivity and performance and customer perceptions of the establishment. The study addressed four-star hotels and aspects related to cleaning, attention to detail, and comfort [39]. In their analysis of the ethical responsibility in some tourism subsectors, [40] suggested that advertising aimed at highlighting the ethical behaviour of organizations has a positive influence on the perceived quality of tourism products and intentions to purchase.

However, [37] suggested that despite the acknowledged influence of CSR on customer loyalty, the topic remains relatively unexplored. These authors also suggested that customers are likely to believe that socially responsible companies operate in a more honest way and that they are willing to use companies that implement CSR actions. Thus, some CSR initiatives can be effective instruments to increase the level of trust between hotel companies and their clients.

Some authors have suggested that real commitment to sustainability can only come through consumer pressure, and that innovation and improved quality and corporate image is determined by customer pressure ([39,40]). Thus, hotels wishing to build loyalty in some segments by implementing CSR should focus their attention on designing policies and strategies that would lead customers to perceiving them as socially responsible brands. This approach would require mechanisms by which to provide consumers with credible information about the companies’ CSR activities [38].

Needless to say, in the interests of brevity (all the papers have a limit of words for publication), we have centred our analysis in the literature related to both the tourism sector and the European Union Countries. However, CSR has been analysed in very different sectors and countries. For instance, [41] did a cross country analysis between the UK and Italy before the introduction of non-financial reporting directive comparing and obtaining as main result the importance of national and sub-national CSR policies to implement corporate social disclosure.

The lack of transparency on firm’s websites is analysed, among others, in [2,42]. That first paper expands the conceptual framework of dialogic communication on social media by incorporating a social dimension via social presence of firms’ CEOs. In a very interesting paper, [2] study a critical issue in CSR implementations: the communication firm-consumer by the analysis of web-bases CSR communications in the Czech Republic and Ukraine, concluding that TOP 100 companies operating in these countries communicate economic and environmental responsibility activities in the greatest scope, and ethical responsibility activities the least, a fact which corresponds to the frequently exclusively philanthropic approach to the concept of CSR in these countries.

Also, in Czech Republic, [43] tried to identify socially responsible practices applied by the statutory cities this country in order to analyse and evaluate the scope and structure of socially responsible activities performed by them and communicated on the internet obtaining similar results that the obtained before for Czech companies. In Romania, [44] analysed the correlation between profit and the decision to do CSR activities and tried to identify the correlations between the level of CSR activities and the dimension of profit, obtaining that the companies which implement CSR activities in a greater extent are more profitable in economic terms.

The concept of stakeholder engagement has been also analysed. [45] analyse this aspect of the CSR in the European banking sector concluding highlighting areas in banking that can be strengthened to improve SE processes; [46] concludes demonstrating that whilst specific types of value may vary according to the OC context, culture and purpose, our investigation of the dynamics of OC value creation in terms of stakeholder engagement (cognitive, emotional and behavioural), when linked to the causal mechanisms used to generate profit, yields new and relevant insights.

This brief review of the literature shows that most CSR studies have focussed on company behaviour. We add to the scarce literature on consumer perceptions by addressing consumer behaviour in the face of CSR practices. The aim was to better understand the perceptions of consumers regarding CSR actions and to what extent they value these actions. We also analysed whether CSR actions have a positive influence on the consumers’ perceptions of hotel services and on their final decision when contracting hotel accommodation.

3. Materials and Methods

This study analysed an Andalusian population of internet users who make purchases through the internet. According to the Survey on Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Households 2017 published by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, 2 795 986 Andalusian internet users between 16 and 74 years old used e-commerce for private or household purposes in 2017. This figure represented 44.43% of the Andalusian population in this age range in 2017, and was more than 5 percentage points below the Spanish average for this population group. Three of the e-commerce products most in demand by Andalusian users are accommodation services (43% of internet users), tickets for shows (36.5%), and travel services such as public transport tickets and car rental (35.2%). These percentages are around 10% less than the averages for the Spanish population (i.e. 54.1% for accommodation services, 46.6% for tickets for shows, and 44.7% for travel services). It seems reasonable to assume that some special factors differentiate Andalusian e-commerce users from Spanish e-commerce users as a whole when they make purchases in the tourism sector, and more specifically, in the accommodation sector. The study included a sample of 412 individuals, which was statistically representative of the Andalusian population between 16 and 74 years old that uses e-commerce, which implies a maximum error of 4.85% for a confidence level of 95%. The individuals in the sample were selected among users of opinion websites such as Trip Advisor and Booking, among others. We have mainly used these two opinion websites because they are the most important in the Spanish market. The distribution of individuals by age, sex and province segments has been determined by probabilistic sampling by proportional affixation. Individuals in the random sample were provided with an online questionnaire for the collection of statistical information. The data collection period has been developed between March and May 2018.

We investigated the effects of some CSR actions on demand, based on the relevance customers give to such CSR actions.

The different dimensions used in the present work have been previously analysed in the literature, converting the social, environmental and economic dimensions into the three pillars of social responsibility that should be considered in future decision-making.

Social dimension: it is subject to a lesser analysis than the rest of the dimensions in the specialized literature. The behaviour patterns of the organizations have been analysed and identified [47]. Thus, communication efforts aimed at highlighting the ethical and social behaviour of organizations have a positive influence on the perceived quality of tourism products and the intention to purchase. In the case of Spain [48] and specifically in Andalusia, some case studies show how certain quality standards (obtained through external certifications to companies) help improve the hotel’s productivity [11].

Environmental dimension: some works identify the increase in consumer sensitivity to environmental issues [49]. The study of environmentally proactive behaviours is repeated in the specialized literature, making it necessary to give greater emphasis on how economic and social objectives can be combined with environmental objectives to achieve greater efficiency [50], and thus, to reduce uncertainty towards these dimensions [51].

Economic dimension: this dimension constitutes one of the engines of economic development [52], with the appearance of different interest groups, perspectives and economic dimensions in the analysis [53]. The hotel industry is not immune to the different dimensions of analysis [54]. The location of the hotels (coast, city or natural places), conditions the perspectives of consumers, although those located in natural landscapes use the environment as a tourist claim resource, those located on the coast or urban environments are obliged to implement specific environmental management measures.

We investigated the latent factors related to the three dimensions of CSR that may affect consumer perceptions using a statistically validated 26-item questionnaire (Table 1) developed in previous studies. The work has a confirmatory character, based on those previous studies. The Likert scale is used to measure the importance of the different variables. For optimal inclusion, a preliminary test of the questionnaire was carried out among professionals (academic researchers and tourism consultants) to determine possible errors in the design of the questionnaire and/or in the transcription of the data that had to be collected, to guarantee the quality of the information obtained, analyse the absence of data and observe the level of coherence in the answers given.

Table 1.

Latent Factors.

We formulated three main hypotheses on the effect of the three CSR dimensions implemented by hotels on consumers’ perceptions of their accommodation services:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

The social dimension of CSR (CSR-S) has a direct effect on customer perceptions of hotel services (CPH).

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

The environmental dimension of CSR (CSR-En) has a direct effect on the economic dimensions of CSR (CSR-Ec) and CSR-S.

Two sub-hypotheses of H2 were formulated: H2.1: CSR-En has a direct effect on CSR-S; H2.2: CSR-En has a direct effect on CSR-Ec.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

CSR-Ec has a direct effect on CPH.

We tested these hypotheses using a reflective model in which each latent variable is the cause of the corresponding observed variable. The observed variables (i.e. measures) are therefore a reflection of the dimensions of CSR and consumer perceptions. The data were analysed using partial least squares (PLS) methodology, which is a methodology that combines two techniques of multivariate analysis: principal components analysis and the multiple linear regression.

There are multiple advantages in the use of the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique ([55,56,57]), among which the following can be highlighted:

- Predictive character that allows the planning and future decision making of the agents involved.

- A very large sample size is not necessary.

- A lower initial requirement in the distribution of the variables that are integrated in the sample.

- The PLS methodology does not assume variable normality and estimates least squares recursively.

- It is also more suitable than the maximum likelihood method for predictive models or for the exploratory and developmental stages of a theory.

The main disadvantage of this technique, which does not invalidate its use as confirmed by the extensive literature in this field, is that the PLS regression is a correlative rather than a causal model, in the sense that the models obtained do not offer fundamental information about the phenomenon studied, since you do not work with the original variables.

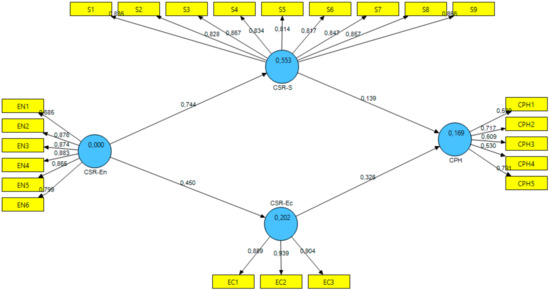

The structural sub model to be estimated was based on four latent factors and their respective indicators included in the reflective measure sub model. The reflective model provided the basis for the four hypotheses that were finally tested. The variable that represented the customers’ perceptions of services and quality was considered an exogenous variable, which could thus affect other factors. The foregoing aspects were based on previous literature in this field of research [58]. Figure 1 shows a nomogram representing PLS estimations using the SmartPLS 3 software package [59]. We draw attention to the results of individual item reliability testing, which has been used in similar contexts [55]. In any case, a cut off of < 0.4 was applied using an item-trimming process [60].

Figure 1.

Structural Sub-Model.

4. Results

The results shown in Figure 1 confirm the appropriateness of the indicators selected. Similarly, the reliability measures shown in Table 2 confirm the validity of the questionnaire used to assess the four latent dimensions proposed. The index of goodness-of-fit proposed by [61] as the geometric mean of the average communality and the average R2 had a value of 0.451. This index is a working solution to the problem of the lack of optimization of scalar functions in PLS modelling and can provide an overall validation of the model.

Table 2.

Reliability Measurements.

As shown in Table 2, the indicators used to verify the reliability of the measuring instruments and internal consistency (i.e. Cronbach’s alpha and the composite reliability indexes) were in all cases more than 0.7 or very close to 0.7. Therefore, the reliability of the constructs was confirmed by their fulfilling the criterion proposed by [62]. In addition, the higher values of the composite reliability index in the PLS model have the advantage over Cronbach’s alpha values of there being no need to assume that all indicators have the same weighting [63].

According to the criteria established by [63] to obtain convergent validity, the values of the average variance extracted (AVE) for the four constructs were more than or very close to 0.5. In addition, the items are placed on the latent variable, where together they increase its quantitative load and the criterion proposed by these authors to test discriminant validity was also fulfilled. That is, a comparison of the amount of variance captured by the construct (AVEj) and the shared variance with other constructs (ρij) for the four latent variables (Table 3) showed that the values of the square root of the AVE of each construct were more than the estimated correlation between them (1):

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix of Latent Variables.

In the case of the predictive capacity of the structural sub-model (see Table 2), the estimated values of the R2 statistic were more than 0.1 for all latent and significant variables. Therefore, the acceptability criterion proposed by [64] was fulfilled.

Table 4 shows the estimations of the direct and total effects between the latent variables of the study model. As shown, the dependency relationships in the proposed model were verified, and they also confirm the study hypotheses. These results are in line with those obtained by [58] for a sample of Spanish consumers. However, CSR-S had a weaker effect on Andalusian CPH than it did on Spanish CPH.

Table 4.

Direct and Overall Effects Between Latent Variables.

With the aim of confirming the theoretical assumptions on which the hypotheses are based, Table 5 shows the estimations of the standardized regression coefficients of the constructs and their corresponding t-statistics using bootstrapping with 5000 samples. The estimated values confirm the statistical significance of the coefficients related to each of the proposed relationships. The signs of these values also confirm the primary and secondary study hypotheses.

Table 5.

Tests of the Hypotheses of Direct Effects Between Latent Variables.

The results presented in Table 5 show the relevance to Andalusian clients of the three dimensions of the CSR initiatives (i.e. economic, environmental, and social) implemented by hotels. It is noteworthy that the relevance of the economic and environmental dimensions reached 99%.

The PLS model provides an assessment of the predictive capacity of our model, by indicating the variance explained by the predictor variables of the endogenous construct in the model. Although its predictive capacity was weak in the case of the social dimension, it was moderate or strong in the other two cases [65].

5. Discussions

This study used a sample of 412 individuals, which was statistically representative of the Andalusian population between 16 and 74 years old that uses e-commerce. We analysed the covariance structure of the factors related to the different dimensions of CSR and to the services provided by hotel establishments, following the methods describes in [58]. The results of the questionnaire used to create the study database show that customer perceptions of hotel services are influenced by four latent factors. The relationships established between those latent factors provided the basis for formulating the three main hypotheses and two sub-hypotheses. All these hypotheses were confirmed.

Firstly, H1 was confirmed, despite CSR-S having the weakest positive effect on customer perceptions (0.139), with Andalusian customers having lower scores than Spanish customers. This result contradicts, in the Andalusian case, the results suggested by [40] or, for the case of Peru by [7], but is in line with the conclusions of [9] for the case of Mexico, where it states that both consumers as the managers of the hotel companies do not know how to recognize hotels’ efforts in social matters, especially due to the difficulty of specific certifications since the existing ones tend to value the quality [66] but not how it has managed to reach that certain level quality. As [67] pointed out, many companies report their CSR goals, but only a few of them provide details of specific initiatives which they have undertaken. As we show in the literature review, communication of the CSR efforts seems to be the “Achilles heel” for companies, as [3] and [45] demonstrated for the case of UK and Italy, [42] for the United States, [46] for the case of Australia and [2] in Czech Republic. In this last country, some authors obtained similar results on this issue for different sectors of the country: [68] for the gambling sector, [69] for the chemical industry and [70] for sugar companies.

If companies pay more attention to this, and according to the results obtained in [71] for the case of Colombia and suggested by [44] for Romania, consumers would be willing to pay a higher price if the company meets certain characteristics in its management, such as commitment to the environment, good treatment of workers and support for anti-poverty programs, among other variables; that is, they would be willing to pay more for business attributes linked to social responsibility.

Secondly, H2 was confirmed in that CSR-En had a positive effect on CSR-S (0.744) and CSR-Ec (0.450). Furthermore, the two sub-hypotheses were confirmed in that CSR-En had an indirect positive effect on customers’ perceptions of hotel services (0.250). These results show that environmental commitment on the part of hotel establishments, and therefore their greater environmental awareness, is highly relevant to Andalusian consumers. These results come to confirm those already obtained for the Spanish case by [15,16,17], among others, or for the international case by [22] or [72], which reinforces our own investigation.

Thirdly, H3 was confirmed in that CSR-Ec had direct positive effect on customers’ perception of hotel services (0.326). This result was as expected according to the relevant literature in this section [20,21,22,23].

In summary, the study hypotheses were confirmed, showing that the model was useful in determining the effect of the different dimensions of CSR on consumer perceptions of hotel services. Nevertheless, the model showed that the economic and environmental factors of CSR are more relevant to consumers than the social components of CSR.

6. Conclusions

It appears reasonable to conclude that customers of hotel services have an increasing interest in business attitudes that promote the greater involvement of hotel establishments in their environmental, social, and economic setting. The results should be taken into account by those responsible for hotel offers, because their involvement in activities related to CSR can be determinant of customer acquisition and loyalty. The strong predictive capacity of the model could be useful to managers by allowing them to adjust the different dimensions of the CSR to the individualized management of the establishments. But, particularly, our findings obtained for the environmental issue could be of interest to hotel managers to guide their investment strategies, which could help them differentiate the services they offer from those of the competition.

Another interesting element to be considered by managers of accommodation companies is the fact that it is difficult for consumers to perceive the efforts of these companies in everything related to the social dimension. The creation of some type of certification that allows such recognition (as in the case of quality certifications, for example) would be an element to be considered by companies. As [71] and [72] pointed out, in the Spanish tourism sector any of the quality models and certifications studied (including ISO 9001 and ISO 14001, EMAS and others), only the Spanish Q-Mark certificate is significantly awarded for consumers.

Also, the participation of employees and even suppliers in promotion campaigns of the establishment, as is common practice among many companies in other sectors, could be a signal to consumers that they are satisfied with their participation in the company and that the behaviour of the company is guided by ethical standards. The communication of the CSR measures implemented by firms and institutions is an issue of critical importance. Efforts in this field are useless if there is no communication between the stakeholders or if it is not running in the correct way.

Finally, this study is limited by the fact that data were not available on consumer socioeconomic variables, such income level, employment status, or cultural level. Some studies on CRS have demonstrated the relevance of these variables for a more detailed analysis [73,74,75,76]. Had these data been available, the study could have provided more specific conclusions. Nevertheless, this limitation could act as a stimulus for future studies using other methodologies.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to each parts of this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Tetrevova, L.; Patak, M.; Kyrylenko, I. Web-based CSR communication in post-communist countries. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Pizzi, S. Ethical firms and web reporting: Empirical evidence about the voluntary adoption of the Italian “legality rating”. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 14, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, F.; Franch, M.; Rizio, D. Environmental management practices for sustainable business models in small and medium sized hotel enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.M.; Alonso, M.; Celemín, M. Responsabilidad social corporativa en las cadenas hoteleras españolas. Un estudio de casos. Revista de Responsabilidad Social de la Empresa 2013, 13, 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; García-Pozo, A.; Marchante-Lara, M. The environment and competitive strategies in hotels in Andalusia. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2011, 10, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal Peralta, J.; Leo Rossi, E.; Navarrete Álvarez, M. Responsabilidad Social Empresarial de los servicios hoteleros: Valoración de los consumidores. Revista Académica y Negocios 2019, 4, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, E.E. Responsabilidad Social Empresarial y gestión ambiental en el sector hotelero; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Sánchez, A.R.; Vargas Martínez, E.E.; Castillo Nechar, M.; Zizumbo Villarreal, L. Responsabilidad Social Empresarial en la hotelería. Un enfoque ético. Gestão Regionalidade 2018, 34, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligor-Cimpoieru, D.C.; Partenie-Munteanu, V.; Nitu-Antonie, R.D.; Schneider, A.; Preda, G. Perceptions of Future Employees toward CSR Environmental Practices in Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Ons-Cappa, M.; Febrero-Paño, E. An analysis of environmental proactivity and its determinants in the hotel industry. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, I.; Gémar, G.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L. Are green hotels expensive? The impact of eco-friendly policies on hotel prices in Spanish cities. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pozo, A.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Ons-Cappa, M. Eco-innovation and economic crisis: A comparative analysis of environmental good practices and labour productivity in the Spanish hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Celemín, M.; Rubio, L. Use of different sustainability management systems in the hospitality industry. The case of Spanish hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gil, M.J.; Burgos-Jiménez, J.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.J. Analysis of environmental management, organizacional context and performance of Spanish hotels. Omega 2001, 29, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Moreno, E.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.; Burgos-Jiménez, J. Enviromental strategies in Spanish hotels: Contextual factors and performance. Serv. Ind. J. 2004, 24, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.F.; Claver, E.; Pereira, J.; Tarí, J.J. Environmental practices and firm performance: An empirical analysis in the Spanish hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M.D.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E. The whole relationship between environmental variables and firm performance: Competitive advantage and firm resources as mediator variables. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3110–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.M.; Rodríguez, J.M. Organisational behaviour and strategies in adoption of certified management systems. An analysis of the Spanish hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Boluk, K. Using CSR as a tool for development: An investigation of the fairhotels scheme in Ireland. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 14, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X. Doing good to do well? Corporate social responsibility rea-sons, practices and impacts in small and medium accommodation enterprises. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Lee, S. Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Lee, S.; Huh, C. Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, S. Do socially responsible activities help hotels and casinos achieve their financial goals? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, O.; Ionescu-Somers, A.; Steger, U. The business case for corporate sustainability: Literature review and research options. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Law, R. You do well and I do well? The behavioral consequences of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.M.; Kim, N. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.; Rodrigues, L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pozo, A.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Marchante-Mera, A. Environmental sustainability measures and their impacts on hotel room pricing in Andalusia (southern Spain). Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 1971–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.A.; Vargas-Vargas, M.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C. Personal attitudes in environmental protection. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2012, 6, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva Álvaro, J.J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez Martínez, F.J. Rural tourism: Development, management and sustainability in rural establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moreno, A.; Díaz-García, C.; Sáez-Martinez, F. Environmental responsibility among SMEs in the hospitality industry: Performance implications. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 1527–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Hurtado-Torres, N.; Sharmac, S.; García-Morales, V.J. Environmental strategy and performance in small firms: A resource-based perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, S. Adoption of voluntary environmental tools for sustainable tourism: Analysing the experience of Spanish hotels. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the global hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P.; Rodríguez Del Bosque, I. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Perez, A.; Rodríguez Del Bosque, I. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 2014, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró-Signes, A.; Segarra-Ona, M.; Verma, R.; Mondéjar-Jimenez, J.; Vargas-Vargas, M. The impact of environmental certification on hotel guest ratings. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchoo, W.; Butcher, K. The influence of ethical responsibility initiatives on perceived tour program quality and tour booking intention. In Proceedings of the International Hospitality and Tourism Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F.; Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S. The state of art of corporate social disclosure before the introduction of non-financial reporting directive: A cross country analysis. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Tsai, W.H.S.; Chen, Z.F.; Ji, Y.G. Social presence and digital dialogic communication: Engagement lessons from top social CEOs. J. Public Relat. Res. 2018, 30, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrevova, L.; Jelinkova, M. Municipal Social Responsibility of Statutory Cities in the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hategan, C.D.; Sirghi, N.; Curea-Pitorac, R.I.; Hategan, V.P. Doing Well or Doing Good: The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profit in Romanian Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Cosma, S.; Leopizzi, R. Stakeholder engagement: An evaluation of European banks. Corp. Soc. Res. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, C.L.; Campbell, J.; Moore, S.; Simpson, J. Creating value in online communities through governance and stakeholder engagement. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2018, 30, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the hospitality industry: some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secondi, L.; Meseguer-Santamaría, M.L.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Vargas-Vargas, M. Influence of tourist sector structure on motivations of heritage tourists. Serv. Ind. J. 2011, 31, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.W.; Hawkins, R. Attitude towards EMSs in an international hotel: An exploratory case study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasin, F. Sustainability: Are we all talking about the same thing? State-of-the-art and proposals for an integrative definition of sustainability in information systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference ICT for Sustainability, Stockholm, Sweden, 24–27 August 2014; pp. 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Glavic, P.; Lukman, R. Review of sustainability terms and their definitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, P.; Everard, M.; Santillo, D.; Robert, K. Reclaiming the definition of sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2007, 14, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, R.G.; Rosenhead, J.; Salhofer, S.P.; Valle, R.A.B.; Lins, M.P.E. Definition of sustainability impact categories based on stakeholder perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissen, F. Sustainable hospitality: A meaningful notion? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use as an Ilustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least square latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Emerald JAI Press: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mondéjar Jiménez, J.; Sevilla-Sevilla, C.; García-Pozo, A. Environmental, Social and Economic Dimension in the Hotel Industry and its Relationship with Consumer Perception. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS3; University of Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2013; Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems re- search using partial least squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The Assessment of Reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.; Miller, N. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Velasco, C.; Quintana-García, C.; Marchante-Lara, M. Total quality management, Corporate Social Responsibility and performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grosbois, D. Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrevova, L. Communicating CSR in High Profile Industries: Case Study of Czech Chemical Industry. Eng. Econ. 2018, 29, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrevova, L.; Patak, M. Web-Based Communication of Socially Responsible Activities by Gambling Operators. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrevova, L. Communication of socially responsible activities by sugar-producing companies. Listy Cukrov. Repar. 2017, 133, 394–396. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pozo, A.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Marchante-Mera, A. Environmental Good practices, quality certifications and productivity in the Andalusian hotel sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; García-Pozo, A.; Marchante-Lara, M. Measuring the effects of quality certification on labour productivity. An analysis of the hospitality sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1100–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquina, P.; Reficco, E. Impacto de la Responsabilidad Social Empresarial en el comportamiento de compra y disposición a pagar de consumidores bogotanos. Estudios Gerenciales 2015, 31, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, C.A.; Siquaw, J.A. Best hotel environmental practices. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1999, 40, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.R.; Vargas, E.E.; Delgado, A.; Rodríguez, F. Responsabilidad Social en la Hotelería. Una percepción desde el turista de negocios. Investig. Adm. 2017, 46, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel Lyne, L.; Hernández Ángel, F.; Ochoa Hernández, M.L.; Garza Arroyo, M.A. El efecto de la Responsabilidad Social Corporativa percibida en el comportamiento de compra de los nuevos consumidores dominantes. In Global Conference on Business and Finance Proceedings 2018; The Institute for Business and Finance Research: San Jose, CR, USA, 2018; Volume 13, pp. 309–318. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).