1. Introduction

Increasingly, stakeholders inside and outside organizations are raising concerns about corporate issues such as workforce diversity, employee treatment and environmental protection. These issues are often grouped together and labelled sustainability or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) [

1]. Properly understood, CSR requires businesses to make an effort to create a non-discretionary, safe and fair working environment for employees which addresses diversity, develops environmentally friendly policies, promotes fair distribution of profits in society and encourages ethical business practices [

2].

Sheehy (2014) defined CSR as “international private business self-regulation.” From the normative perspective, all regulations are set to serve some specific purpose. So, if the organization claims to have a CSR policy then it must include of all its aspects, that is, environmental sustainability, human rights, employment conditions, business practices in dealings with partners, suppliers and consumers and social impacts starting with basic conformity with the established legal framework and then gradually moving towards the consideration of stakeholder concerns [

3].

Of all the features of CSR mentioned above—that is, the environment, philanthropy and community development—employee focused CSR which leads to the fair and responsible treatment of employees is of particular importance. Research shows that an organization’s reputation as a socially responsible employer has become significantly crucial for its CSR rating. If employees are excluded from CSR, then it merely becomes a marketing strategy. Therefore, if CSR is to be effective, organisations have to go beyond the legal requirements regarding employee rights and needs by valuing and treating them well [

4,

5,

6].

The term internal dimension of Corporate Social Responsibility refers to this kind of socially responsible behavior on the part of the organization towards its employees. Socially responsible behavior towards employees is manifested through a range of CSR activities, such as endorsing employment stability, creating a positive working environment, skills development, diversity, work-life balance, empowerment and tangible employee involvement [

7].

In the past, CSR research has mainly been conducted at the macro-institutional level [

8] and has mostly focused on the link between CSR and corporate financial [

9,

10] and competitive performance [

11]. Researchers have mainly concentrated on the external component of CSR and the interests of external stakeholders by addressing issues such as environmental sustainability [

12], corporate philanthropy [

13] and community development [

14].

Recently, researchers have started to point out the gap in the research that past studies on CSR have often overlooked—a micro-level analysis of employee-related outcomes of CSR [

15]. Employees are the key stakeholders of the organization and they are involved in, contribute and respond to the organization’s CSR policies, especially those that are directly linked to them. Their evaluations of those CSR initiatives are subsequently connected with the fulfilment of their psychological needs, which in return influence their work attitudes and behaviors. Here it is worth noting that employees’ cultural perspectives affect the way they perceive, interpret and relate to CSR initiatives. The cultural variability of the CSR concept and its implementation is an established fact in previous research [

16]. There are specific cultural characteristics, such as collectivism, which have a high probability of affecting CSR and its implications and which can be a direct product of traditional cultural predispositions [

17]. Therefore, the inclusion of cultural context in CSR studies can enhance the understanding of the determinants and consequences of CSR.

In light of the aforementioned discussion, this study is intended to move forward the academic debate on CSR research by focusing especially on providing an improved understanding of employee-focused CSR. It is imperative to develop and empirically test the theoretical models that can explain the underlying mechanisms that address questions such as how and when the internal dimension of CSR is linked with employee outcomes in a specific cultural context.

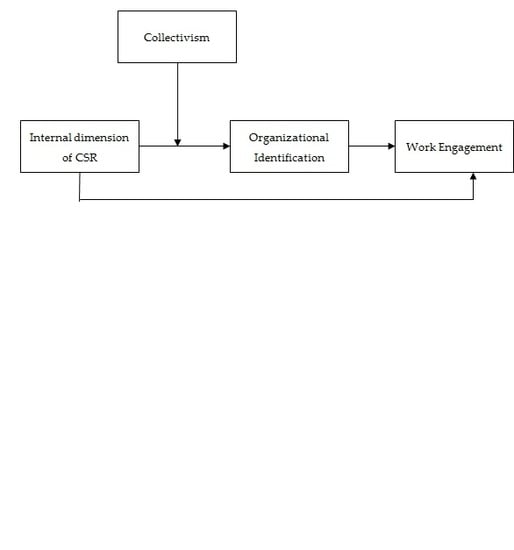

Therefore, the current study aims to theoretically contribute to the literature by proposing and analyzing the underlying mechanisms that can explain how and when the internal dimension of CSR affects employee behavior by employing three constructs: Organizational Identification (OI), Work Engagement (WE) and the cultural dimension of collectivism. The paper is organized in the following sections: the literature review is presented in

Section 2 and

Section 3 highlights the data and methodology used to examine the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR, work engagement, organizational identification and collectivism.

Section 4 discusses the main findings of the paper. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the results and

Section 6 summarizes the conclusions of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Work Engagement

Work engagement is defined as an affirmative, satisfying mental state related to work. In fact, it is not a specific mental state over the short term but an implicit affective–mental state over the long-term and is not mainly directed towards any situation, thing or individual. Work engagement has three dimensions: vigor, dedication and absorption. Vigor is mental resilience, with high levels of energy applied to work, a readiness to devote efforts at work and the demonstration of perseverance in difficult times. Devotion is the involvement of the individual in work with a sense of accomplishment, passion, motivation, pride and defiance [

18,

19]. Absorption is the involvement of the individual in work to the extent that time passes quickly and that he/she finds it difficult to disassociate him/herself from work [

20].

Recent studies indicate that CSR activities humanize the company in a way that other job components cannot, and is a source of competitive advantage [

21]. It indicates that the company is not only a profit-making entity but is concerned about all stakeholders. The paycheck alone cannot keep employees emotionally connected with their jobs; in this regard, CSR can serve as a differentiation point to emotionally connect employees with their work [

22].

Researchers have discussed the link between the four dimensions of CSR and work engagement. Lin [

23] argued that economic CSR makes employees more engaged in their work because they perceive that the organization is doing well for them economically in order to provide them with stable and necessary work and life quality. Legal CSR reduces the adverse effects on the employee in the form of stress, anxiety and insecurity, of which result in disengagement of the employee from work. Ethical CSR motivates and stimulates employees in a business to be positive towards their organization and their jobs, resulting in higher work engagement. Discretionary CSR also increases work engagement because work engagement itself is a discretionary effort on the part of employees to enhance organizational effectiveness. So, when they see the organization going the extra mile to support the community in the form of corporate philanthropy and community involvement, this enhances the employees’ feeling of meaningfulness and their determination to do their jobs.

Social Exchange Theory (SET) can be used to provide the theoretical foundation for explaining the link between Internal CSR and work engagement. SET proposes that human interactions are regulated by a subjective cost and benefit analysis and is based on the comparison of alternatives [

24]. According to SET, the social exchanges between the employees and organization are mostly symbolic and grounded in intangible resources and the exchange process is regulated by the norms of reciprocity. There is considerable research evidence in support of reciprocity norms. The norms of reciprocity are based on the dispositional orientation of employees according to which employees should help those who have supported them in the past [

25]. Employees reciprocate the benefits received from the organization, such as sincere concern shown by the organization about their well-being and fulfilment of implicit promises.

Various models of social exchange have been applied to various aspects of work, such as turnover intentions, organizational citizenship behavior, trust in management and the psychological contract. SET is an influential motivational framework for explaining the specific engagement of employees in discretionary behaviors, since these behaviors are neither obligatory nor recognized by any organizational formal reward systems. For such behaviors, social exchange is analogous and can refer to the common interactions that are continuously evolving with no time limit and are based on social benefits [

26].

The internal dimension of CSR is the treatment of employees in a socially responsible way and it can determine the way employees will behave in the organization. When employees perceive that management has a caring attitude to them, they will reciprocate the caring behavior and will be more willing to fulfil their responsibilities towards the achievement of organizational goals [

27]. Employees are adaptive; they scan and interpret the clues in the working environment and develop attitudes. When a company has a high CSR standing and high ethical standards and practices, it is perceived as a reliable business partner and a respectable member of the business community [

28]. CSR gives a positive signal and indicates to employees that the organization is compassionate towards them. Internal CSR increases self-esteem, optimism and a sense of appreciation, as a result of which employees are more likely to end up with a high level of engagement in their working tasks. Here it is proposed that when the employees perceive that the organization is investing in employee relations, they can feel valued by the organization and this consequently leads to greater engagement with work.

H1: Internal dimension of CSR will be positively related to work engagement.

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Identification

Organizational identification appears when the values of the employees correspond with the values of the organization; alternatively, it can be expressed as the feeling of togetherness or belongingness to the organization [

29]. Social Identity Theory (SIT) can be used to explain the link between the internal dimension of CSR and organizational identification [

30]. According to SIT, social identity is people’s perception of who they are, based on their group membership. This group membership can be a vital source of their self-pride and self-esteem [

18]. There are three facets of SIT: (1) Categorization: assigning people into distinct categories; (2) Social identification: adopting the identity of the group that the individual has identified as belonging to and (3) Social comparison: comparing the group of belongingness to other groups. Group membership gives people a sense of belongingness. As a result, they strive to improve the image of the group which they belong to.

In the case of CSR, employees are more likely to identify with those CSR initiatives that are aligned with their values [

31]. CSR policies, as compared to other corporate policies, show the character of the company, which is not only significant and long lasting but also distinctive. Moreover, companies that engage in CSR are more likely to have a better public image, which develops a sense of pride in their employees [

32]. Past literature shows that an effective CSR strategy gives organizations more flexibility to deal with different situations, such as emerging crises, goodwill improvement or other social and ethical issues, and, most importantly, allows them to build the moral and ethical climate through which they can practice their core values [

33]. Thus, it can be argued that CSR enhances organizational attractiveness by fulfilling an employee’s need to work for socially responsible companies. The employees of such companies have improved self-esteem, which increases their organizational identification (OI) [

34]. Previous studies support the specific link between CSR and organizational identification [

35,

36,

37].

Employees are significant stakeholders of the organization and also the biggest challenge for social responsibility, for example, in the industrial sector one of the potential threats to an organization is the loss of human potential and the low salary of employees [

38]. Internal dimension of CSR is more specifically related to actions directed towards employees. For example, researchers have compared CSR directed towards employees with High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS) and argued that there exists an active link between Human Resource Management (HRM) and internal dimension of CSR as both deals with employees. HRM practices, that is, pay for performance, training and development and empowerment, have previously been found to be strongly associated with organizational identification [

39] and these practices have many similarities with CSR actions primarily directed towards employees [

40]. Moreover, the literature shows that CSR can be a strong predictor of organizational identification because it comprises actions that are positively perceived by employees and assures them that the organization cares, respects and values them [

41]. The literature on social identity also suggests that employees evaluate their internal status in the organization to determine whether they are valued and competent members of the organization. These evaluations effect their perceptions of respect. So here it is argued that CSR actions directed towards employees send signals to employees that the organization is respectful and conscious about their wellbeing, which will consequently increase the employees’ organizational identification.

H2: Internal dimension of CSR will be positively related to organizational identification.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Collectivism Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Identification

In this debate, it is interesting to include cultural perspectives, as both CSR perceptions and practices and organizational identification vary across cultures and take different forms. Collectivism is selected and considered a suitable dimension for current research as it is relevant to the theoretical model in the sense that organizational identification explains the individual behavior in the group [

42]. Collectivist cultures are those where, from birth, people are assimilated in groups and focus on interdependence, group goals, equality norms and collective harmony. In a collectivist society, people place more importance on the welfare of others, as compared to individualist societies where the focus is on individual self-interest. The members of a collectivist culture perceive themselves as part of an extended family or organization. Consequently, they believe that the other members of the group should take care of them and in return, they grant them their loyalty [

43]. Overall, individualists are less concerned and emotionally attached within-groups [

44]. In Eastern collectivist cultures, individuals seek acceptance and are in search of peaceful interdependence. Relationships constitute a significant element of self-definition in collectivist cultures [

45].

The essential characteristic of a collectivist culture is that individuals may be persuaded to subordinate their personal goals to collective goals, which are typically representative of some in-group (for example family, society, organization). Individuals in in-groups tend to have more stable relationships in collectivist cultures and they are ready to make any compromises to the rigorous demands of the in-group. However, unlike those living in collectivist cultures, individualists tend to drop existing in-group memberships and form new ones if they perceive demands to be inappropriate and too challenging. Therefore, the demands of the in-group in individualist cultures are highly specific to a certain time and place as compared to the demands in collectivist cultures which are often diffused. In individualist cultures, individuals perceive themselves as autonomously distinctive from other members, either as individuals or groups. However, in a collectivistic culture an individual’s distinctiveness is based on in-group and out-group membership [

46]. Therefore in collectivist cultures, individuals will have a high probability of identifying with their social groups, which include their organization [

47].

Employees with a collectivist orientation may be keener to define themselves positively as part of the employing organization; they may be more willing to relate to the organization and its goals due to their preference for group goals and psychological attachment with the in-group. It is the opposite for employees with an individualist orientation, who will be least likely to identify or disidentify with the organization [

48]. Therefore, it is proposed here that in a collectivist culture the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and organizational identification will be stronger. When the organization engages in CSR policies in a collectivist culture, the employees will be more willing to care about their organization in order to reciprocate the caring behavior of their employer. Due to their collectivist orientation, they will prefer organizational cohesiveness and place more emphasis on organizational goals as compared to self-goals; consequently, they will be more willing to identify with the organization.

H3: Culture will moderate the positive relationship between CSR and organizational identification such that the relationship will be stronger when collectivism is high.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Identification

The literature that supports a possible link between organizational identification and work engagement argues that employees with a strong organizational identification tend to be more motivated to engage in cooperative behaviors that are beyond their job description. They engage in such behaviors due to the direct and indirect influence of their group identity. Employees who strongly identify with their organizations are actively involved in the tasks and goal setting of the organization and are more motivated to work hard for the accomplishment of those goals. Fu et al. (2014) discussed the internalization of organizational goals due to the intense psychological bonding with the organization. When the individual identifies with the organization, he/she is more likely to relate to its perspectives and engage him/herself in positive work attitudes that eventually benefit the organization, such as work engagement [

49]. The theoretical model of work engagement consists of three dimensions—vigor, dedication and absorption—and is linked with organizational identification in such a way that when employees have a strong psychological bond with the organization and internalize the organizational goals, they will be more energetic and mentally resilient in their work (vigor) [

50]. Thus, they will be more devoted to and determined in their work (dedication) and finally, they will be more involved in it (absorption) [

51,

52].

At this point, it is proposed that, through organizational identification, the internal dimension of CSR will positively affect work engagement and positively influence employees’ organizational identification. Therefore, it can be argued that just like individuals, organizations also have goals and objectives. The internal dimension of CSR shows that the employing organization is concerned about the interests and well-being of its employees which may result in an increasing emotional attachment of the employees to the organization. It can make the organization one big unit working as a whole instead of different groups working individually for different goals; the tendency of the organization and its employees to share the same goals increases and consequently the employees’ engagement with work tasks also increases.

H4: Organizational identification will mediate the relationship between CSR and work engagement.

Figure 1 shows the proposed theoretical model of the current study. Internal CSR is the independent variable; collectivism is the moderating variable; organizational identification is the mediating variable and work engagement is the dependent variable of the study.

3. Data and Methodologies

Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect the data. The scales for the variables were measured using the work of previous researchers. The original survey items were used; however, the scales were adapted for length and language to fit the needs of the present study (

Table 1).

There were two main sections of the questionnaire: the first was the demographic section in which the respondents were asked about the organization name, gender and age. The second section incorporated the questions measuring the variables and was divided into four subsections. The number of survey items for the analysis was finalized after all the measures were tested for validity and reliability.

Table 1 shows the details regarding the sources, the number of items and rating scales used for the study.

The study was intended to provide empirical evidence from a collectivist culture on the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and employee behavior. For this purpose, the data was collected from employees working in the top five banks of Pakistan featured in the Top 1000 World Banks by their (2016) capital [

53]. This sample suited the objectives of our study as Pakistan scored 14 on the individualism/collectivism dimension and is therefore considered a collectivist society [

55]. This implies that in Pakistani society, people have close and long-term commitments to the group they belong to (family or organization etc.). Loyalty is of supreme importance over other social norms and values. Strong relationships are fostered in society and people take responsibility for fellow group members. The employer–employee relationship is treated in moral terms and mostly perceived as a family link.

All chosen banks have approved a CSR strategy from the board of directors and their CSR policies are projected quite prominently on their official websites and also in annual reports of the banks. Therefore, the sample was well suited to serve the objectives of the current study. The population was divided into five strata (Banks) and proportionate stratified random sampling was used to collect the data. The total size of the population was 73,000 employees, approximately. The sample size of between 30 and 500 is appropriate for most research but explicitly following the general guidelines for sample size selection, a sample size of 381 is appropriate for a population of 50,000 and 382 is appropriate for a population of 75,000 [

56]. Following these guidelines, the sample size of the current study was comprised of 530 employees working at the various levels and departments of the top five banks in Pakistan.

4. Results

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is used to test the hypothesized model of the current study. In the following section, the results of the measurement model and the path model are shown, along with the reliability and correlation analysis (

Table 2).

In order to test the distinctiveness of the constructs used in the current study, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is conducted. The overall model fit was tested using the goodness-of-fit indices, including the Model Chi-square, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RAMSA) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The results in

Table 1 show the statistics in the case of the 4-factor model (Internal CSR, collectivism, organizational identification and work engagement), where the chi-square value is 3965.405 (

p < 0.01) with 1658 degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF = 2.39 < 3). The RMSEA was 0.05, the SRMR was 0.042, the CFI value was 0.932 and the TLI was 0.927, which indicate a respectable model fitness. Further alternative measurement models other than the four-factor model were also estimated. The results express the fact that the 4-factor model has a better fit than the other estimated models, which confirms that the respondents were able to differentiate between the constructs under examination for the current study

After confirmatory factor analysis, Cronbach’s Alpha was used to measure the reliability of the variables. Cronbach’s Alpha measures the internal consistency of the group of items by measuring the homogeneity of the group.

Table 3 shows the alpha measure for each variable along with the number of items used in the final analysis. Two items of the internal dimension of CSR were dropped during the CFA due to low factor loadings. Cronbach’s Alpha values lie between 0 and 1, with values close to one showing high reliability; the results indicate a high level of reliability for all the scales used, as the values range from 0.858 to a high of 0.962.

Table 3 shows that the scales used for the variables were reliable.

Table 4 displays the results of mean, standard deviations and correlation analysis of the demographic variables (age and education) and the study variables (Internal dimension of CSR, COL, OI and WE). The results of the Pearson Correlation show that CSR is significantly and positively related to organizational identification (r = 0.766,

p < 0.01), collectivism (r = −0.011,

p > 0.05) and work engagement (r = 0.733,

p < 0.01). In order to test the hypotheses, path analysis was conducted in AMOS. All the variables were standardized before this analysis.

Table 4 shows the path analysis for the current study.

The results demonstrate that the internal CSR has a significant positive relationship with work engagement (β = 0.30,

p < 0.001) and organizational identification (β = 0.79,

p < 0.001). Moreover, organizational identification also has a significant positive relationship with work engagement (β = 0.47,

p < 0.001) in

Table 5;

Table 6.

The positive coefficient values strengthen the conclusion that internal dimension of CSR policies are positively and significantly related to work engagement and organizational identification, which leads to the confirmation of hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2. Thus, the results also reveal that the relationship between organizational identification and collectivism is positive but insignificant. However, the estimate of the interaction term (Internal dimension of CSR*Collectivism) is significant (β = 0.143, p < 0.001), confirming that collectivism moderates the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and organizational identification. In order to probe further the interaction effect, the significant interactions were plotted.

The interactions plotted in

Figure 2 show that the positive relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and organizational identification was stronger at a high level of collectivism. The significant coefficient of the interaction term leads to the confirmation of hypothesis 3 of the current study which states that culture moderates the positive relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and organizational identification, such that the relationship is stronger when collectivism is high.

The analysis of the indirect paths shows that the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and work engagement (β = 0.394,

p < 0.001) is significant (see

Table 6) in the presence of organizational identification. However, the direct path between the internal dimension of CSR and work engagement is also significant, which shows that there exists not only a significant relationship between organizational identification and work engagement but that some direct relationship also exists (

Table 5) between the internal dimension of CSR and work engagement (β = 0.301,

p < 0.001). Therefore, the partial mediation is proved and hypothesis 4 of the study can also be confirmed which states that there is a mediating role for organizational identification in the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and work engagement.

5. Discussion

This study is based on the argument that an organization’s socially responsible policies towards employees can have a great influence on their behavior. Further, this study followed the stream of research that debates the variability of the CSR concept across cultural contexts [

57]. The results confirm both the arguments, as all the hypotheses of the study were confirmed. These results are consistent with the findings of previous researchers, who suggest that CSR is an important tool for retaining the greatest talent that a company possesses. Through CSR policies organizations can retain the best talent which will improve their goodwill and consequently improve corporate performance [

28].

The study contributes to the existing literature by highlighting social identity theory and social exchange theory as the powerful mechanisms explaining the linkage between CSR and employee behavior. In this study, social exchange theory and social identity theory are used to create the link between internal CSR and employee behavior. Further, SIT is related to the group behavior that is congruent with the Hofstede national cultural dimension of collectivism, therefore the SIT model provides an examination of the role of collectivism as a moderator in the relationship between internal dimension CSR and organizational identification.

The results of the study also highlight that when the employees perceive that their employer is socially responsible for them, they tend to find the organization a more attractive one to identify with. Previous literature also confirms this finding, suggesting that CSR leads to strengthening organizational identification (SIT) [

15,

32]. Tajfel (1978) differentiated SIT between in-group and out-group behavior. The study supplements this discussion by explaining that internal dimension of CSR can help develop positive differentiation between the in-group and the out-group. Members of the in-group differentiate themselves from the out-group and in this process of differentiation they try to attribute negative traits to the out-group so as to improve their in-group status [

58]. The results of our study imply that CSR is socially desirable, and employees use CSR as a parameter to positively differentiate their employer from others in order to improve their perception of social identity and this group distinctiveness eventually results in a strengthening of their self-esteem. The positive image of the organization increases the willingness of the individual to identify with the organization [

49].

Our proposed model and findings provide insights into the significance of internal CSR policies that can create awareness among researchers and practitioners as to how internal dimension of CSR can be a leading indicator of positive employee behavior. The study provided sufficient support for the relevance of social exchange theory as a theoretical paradigm in understanding the possible mechanism between internal dimension of CSR and employee behavior. Particularly, our findings highlight that CSR investments influence different stakeholders (shareholders, executive management, government, employees, clients, suppliers) and positively affect their attitudes and more specifically their commitment to their employees; for this reason organizations must include CSR values in their business strategies [

38] and give due importance to employees in designing CSR policies.

The study was conducted on a sample from a collectivist society and the findings of our study show that for people belonging to the collectivist cultures of Asian countries such as Pakistan conformity to social relationships are of high value and it is almost impossible to separate the social context of one’s self. In a collectivist culture, when an organization engages in CSR it leads to a strengthening of the emotional bond between the employees and the organization. When the organization engages in initiatives that are related to enhancing the well-being of employees it leads to the satisfaction of their intrinsic and extrinsic needs; as a result, they tend to identify more with the organization.

The results emphasize that CSR initiatives directed towards employees are one of the forms of corporate investments that eventually result in strengthening positive work-related behaviors, that is, work engagement and organizational identification. The internal dimension of CSR is an important indicator of management’s concern about the well-being of employees and is an important proxy in understanding that the internal dimension of CSR in a collectivist culture leads to a strong organizational identification. Employees feel pride in their organizational membership when they strongly identify with it, as they perceive that they are part of a group that is valuable to them [

59]. Consequently, the stronger organizational identification increases the engagement of the employees in positive work behaviors, such as work engagement, because they will be more motivated to benefit the group (organization) they belong to.

CSR, Corporate Image, Reputation and Brand and their outcomes (profit) are linked to the financial [

60] and other benefits for the firm and for society [

61]. The results of the current study highlight the CSR benefits for the firm at the employee level. The findings of our study may provide organizations with another opportunity to improve their competitive position [

62]. CSR strategically linked to organizational objectives is a source of competitive advantage and increases industrial potential. In this context, the findings suggest that the internal dimension of CSR leads to the development of a workforce that can be a source of competitive advantage and improved corporate performance by increasing the desirable employee outcomes [

63]. The organizations that have well-developed CSR policies are in a better position to implement their business strategy, because of the highly satisfied and well-motivated workforce that is ready to engage in positive behaviors, such as work engagement and organizational identification.

6. Conclusions

This research used social identity theory and social exchange theory together as a mechanism to create a link between the internal dimension of CSR and employee-related outcomes. This study addresses the direct interaction of the employee with the organization. The finding of this research shows that if organizations take care of their most important stakeholders - their employees -, this is an investment which ensures that the organization can get a return in the form of the increased engagement of the employees in positive behaviors.

The findings of this study offer empirical evidence for the popularly held assumption that corporate social responsibility and its implications vary across specific dimensions of national culture. Thus, the socially responsible behavior of organizations can be optimized by initiatives that are tailored according to the cultural beliefs and values of the specific country. For collectivist countries like Pakistan, employees are more concerned about ICSR policies and this is manifested in their behaviors. Individuals with a collectivist orientation are more inclined to search for common values and goals and emphasize group goals over individual goals and desires. So, in a collectivist society when an organization introduces CSR policies, the employees will be more likely to identify with the organization due to the fact they have already given more importance to the organization as a group they belong to. Hence, unity and selflessness are considered as valuable traits for them. So, policymakers and practitioners should rethink their CSR strategies in collectivist countries like Pakistan, which are still very philanthropic. Employees should be given due importance as significant stakeholders and in order to protect their rights and interests, CSR initiatives should be introduced.

In connection with the findings presented above, this study has various implications for CSR and organizational behavior literature. First, it offers insights into the internal dimension of CSR in the context of profit-making organizations in Pakistan; thus, it expands the literature related to CSR in the cultural context of South Asian countries. The findings of this study also have important implications for the CSR strategies of organizations, especially CSR policies that are directed towards employees. Organizations that engage in the internal dimension of CSR can have better productivity because ICSR develops a strong sense of employees’ organizational membership that persuades them to engage in positive work outcomes such as work engagement.

Employees are important stakeholders of an organization and their satisfaction is essential for the organization and in order to strive for competitiveness, the organization should develop specific internal CSR programs and further ensure the successful implementation of these programs. CSR initiatives may focus on treating employees fairly, designing challenging jobs, providing proper feedback, giving autonomy and rewarding positive behaviors. These initiatives can help stimulate positive psychic energy in employees, which can increase their engagement in positive work behaviors such as work engagement.

There were several limitations to the current study. First, the study employed a cross-sectional study design which itself poses inherent restrictions in making inferences. Future researchers can employ a longitudinal study design that can better explain the causal inferences. Second, the data for the study were collected from the leading organizations of one industry, which limits the generalizability of the results. The results may vary across different organizational and regional contexts [

64]. In the future, researchers should examine organizations in different industries to elaborate on the understanding of the internal dimension of CSR and its influence on employee behavior.

Moreover, this study highlighted the specific cultural dimension of collectivism in one country but the findings might vary in different countries due to differences in cultural values. So, the findings of this research should be extended to other countries and cultural dimensions. Employing cross-cultural comparisons can improve and expand the theoretical and empirical findings of this approach as well [

65].

In order to explain the relationship between the internal dimension of CSR and employee behavior, the authors emphasized the role of social exchange and social identity theories as mediation and moderation mechanisms. In future, other mechanisms can be employed by researchers, that is, Leader-Member Exchange (LMX), organizational politics and organizational justice to further elaborate on the relationship between CSR and employee behavior. Lastly, an exciting endeavor can be mentioned that is, employing variables from other disciplines, such as macro- and interventional economics, in order to discover how a company’s engagement in socially responsible initiatives can stimulate employees.

Author Contributions

S.Z., R.S., J.V. and J.P. conceived and performed the experiments; S.Z., D.M analyzed the data and S.Z. wrote the paper; J.V. contributed materials and analysis tools.

Funding

The publication is supported by the EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00022 project. The project is co-financed by the European Union and the European Social Fund. This research was funded by National Research, Development, and Innovation Fund of Hungary. Project no. 130377 has been implemented with the support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the KH_18 funding scheme.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the ÚNKP-19-4 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities and by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kot, S. Knowledge and Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Adv. Res. Law Econ. 2014, 5, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B. Defining CSR: Problems and Solutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P. Unilever’s Drive for Sustainability and CSR–Changing the Game. In Organizing for Sustainability; Mohrman, S.A., Shani, A.B., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 41–72. ISBN 978-0-85724-557-1. [Google Scholar]

- Herbus, A.; Ślusarczyk, B. The use of corporate social responsibility idea in business management. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 6, 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ślusarczyk, B.; Broniszewska, A. Entrepreneurship of women in Poland and the EU—Quantitative analysis. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 9, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Mory, L.; Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V. Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1393–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, M.; Zheng, C.; Khuong, N.; Khan, T.; Usman, M.; Sial, M.S.; Zheng, C.; Khuong, N.V.; Khan, T.; Usman, M. Does Firm Performance Influence Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting of Chinese Listed Companies? Sustainability 2018, 10, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakurár, M.; Haddad, H.; Nagy, J.; Popp, J.; Oláh, J. The Impact of Supply Chain Integration and Internal Control on Financial Performance in the Jordanian Banking Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Kovács, S.; Virglerova, Z.; Lakner, Z.; Kovacova, M.; Popp, J. Analysis and Comparison of Economic and Financial Risk Sources in SMEs of the Visegrad Group and Serbia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, P.; Cupertino, S.; Ruggiero, P.; Cupertino, S. CSR Strategic Approach, Financial Resources and Corporate Social Performance: The Mediating Effect of Innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.; Geenen, J.; Jurcevic, M.; McClintock, K.; Davis, G. Applying asset-based community development as a strategy for CSR: A Canadian perspective on a win-win for stakeholders and SMEs. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The Relationship Between Corporate Philanthropy And Shareholder Wealth: A Risk Management Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orlitzky, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Engagement: Enabling Employees to Employ More of Their Whole Selves at Work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S.; Javidan, M. Components of CEO Transformational Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1703–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-C.; Fatima Wang, C.-C. Collectivism, Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource Advantages in Retailing. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jongh, J.; Meyer, N.; Meyer, D.F. Perceptions of local businesses on the Employment Tax Incentive Act: The case of the Vaal Triangle region. J. Contemp. Manag. 2016, 13, 409–432. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, L. Labour relationship quality perceptions and self-esteem of a sample of Tshwane-based employees. J. Contemp. Manag. 2018, 15, 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement With a Short Questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. Reconceiving corporate social responsibility for business and educational outcomes. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P. Modeling Corporate Citizenship, Organizational Trust and Work Engagement Based on Attachment Theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring Employee Engagement with (Corporate) Social Responsibility: A Social Exchange Perspective on Organisational Participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Karatepe, O.M. An examination of the consequences of corporate social responsibility in the airline industry: Work engagement, career satisfaction and voice behavior. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 59, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, W.; Szántó, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Business Ethics in Controversial Sectors: Analysis of Research Results. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2018, 14, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkkonen, M.-E.; Lipponen, J. Relationships between organizational justice, identification with organization and work unit and group-related outcomes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 100, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the Perception of ‘Goodness’ Good Enough? Exploring the Relationship Between Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Organizational Identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonkutė, E.; Vveinhardt, J.; Sroka, W. Training the CSR Sensitive Mind-Set: The Integration of CSR into the Training of Business Administration Professionals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Song, H.J.; Lee, C.-K. Effects of corporate social responsibility and internal marketing on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Ashraf, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Abdullah, M.I.; Ashraf, S.; Sarfraz, M. The Organizational Identification Perspective of CSR on Creative Performance: The Moderating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.-T.; Kim, N.-M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee–Company Identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency Matters! How and When Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Employees’ Organizational Identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpak, N.O.; Stanasiuk, N.S.; Hlushko, O.V.; Sroka, W. Assessment of the Social and Labor Components of Industrial Potential in the Context of Corporate Social Responsibility. Polish J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 17, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR Is a Social Norm. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Farooq, M.; Reynaud, E. Does Employees’ Participation in Decision Making Increase the level of Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability? An Investigation in South Asia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Farooq, O.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Employees response to corporate social responsibility: Exploring the role of employees’ collectivist orientation. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, T.; Yoon, S. Human Resource Management, Individualism-Collectivism and Individual Performance among Public Employees: A Test of the Main and Moderating Effects*. Korean J. Policy Stud. 2009, 23, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, A.; Aravena, C.; Aliaga, V. Information and communication technologies and their impact in the economic growth of Latin America, 1990–2013. Telecommun. Policy 2016, 40, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Bontempo, R.; Villareal, M.J.; Asai, M.; Lucca, N. Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Ando, K.; Hinkle, S. Psychological Attachment to the Group: Cross-Cultural Differences in Organizational Identification and Subjective Norms as Predictors of Workers’ Turnover Intentions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J. The mediation of in-group identification between collectivism and knowledge sharing. Innovation 2015, 17, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.; Wakefield, K.L.; Tanner, J.F. Industrial buyers’ risk aversion and channel selection. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E.; Ashforth, B.E. Evidence toward an expanded model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ye, B.H.; Law, R. You do well and I do well? The behavioral consequences of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanika-Murray, M.; Duncan, N.; Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Organizational identification, work engagement and job satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Buckley, F. Linking trust in the principal to school outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2009, 23, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, X. Procedural Justice and Employee Engagement: Roles of Organizational Identification and Moral Identity Centrality. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and Organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Loyal From Day One: Biodata, Organizational Identification and Turnover Among Newcomers. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival; Wageningen University & Research: Gelderland, The Netherlands, 2010; ISBN 0071664181. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781119266846. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, P.S.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Published in cooperation with European Association of Experimental Social Psychology by Academic Press; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 0126825505. [Google Scholar]

- Mozes, M.; Josman, Z.; Yaniv, E. Corporate social responsibility organizational identification and motivation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Yifan, H.; Lin, W.; Streimikis, J. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility with Reputation and Brand of the Firm. Amfiteautru Econ. 2019, 21, 442–460. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, D.I.; Dabija, D.-C. ISO 26000: A Brief Literature Review. In ISO 26000—A Standardized View on Corporate Social Responsibility; Idowu, S.O., Sitnikov, C., Simion, D., Bocean, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 81–92. ISBN 978-3-319-92650-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Liang, H.; Zhan, X. Peer Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chwistecka-Dudek, H. Corporate Social Responsibility: Supporters vs. Opponents of the Concept. Forum Sci. Oeconomia 2016, 4, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.F.; Meyer, N. A Comparative Analysis of the Perceptions of Business Chambers in Rural and Urban South Africa on the Developmental Role of Local Government. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 14, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulficar, S. The Impact of Internal Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Behavior: Evidence from Leading Banks in Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, 29 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).