Abstract

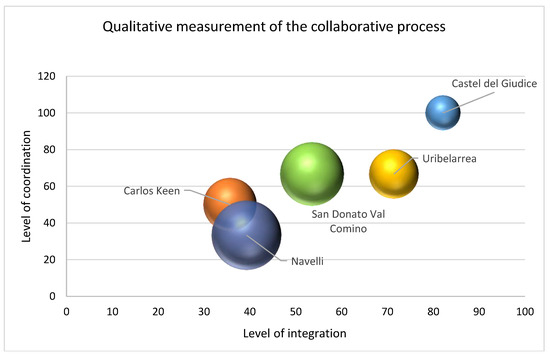

Multi-case-study research conducted in some rural villages of Argentina and Italy is intended to propose a model of analysis and monitoring of the “collaborative processes” which stands behind the tourist enhancement of local assets. Based on the definition of “collective impact”, three main issues are analyzed: (1) the shortage of social capital, typical of some contemporary rural areas as a social problem; (2) the commitment of actors from different sectors to the common agenda of tourist development; (3) the structured form of coordination driven by extra-local organizations and programs, aimed at fostering sustainable tourism in rural villages. These issues are developed into key concepts used for the comparative description and analysis of the cases and for the definition of a common model of measurement and monitoring of the ongoing development processes. The main results are synthesized into a bidimensional plot, where the x-axis represents the “integration” dimension and the y-axis the “coordination”. Each village is then represented as a point of the Cartesian plan. The final idea is to use the model to monitor the processes within each different rural village and to measure the changes over time.

1. Introduction

The definition of “collective impact” introduced by Kania and Kramer [1] as “the commitment of a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem” (p. 36) offers the opportunity to focus on the processes and the dynamics that tourist development may trigger in peripheral rural areas. In particular, from the definition itself, three main issues are identified and used as pillars of a theoretical framework for the comparative analysis of some case studies in rural tourist villages of Argentina and Italy. These issues can be briefly described as follows: (1) the shortage of social capital, typical of some contemporary rural areas, as the social problem to be addressed in order to achieve sustainable tourism development through a collaborative process; (2) the commitment of actors from different sectors to the common agenda of rural tourist development; (3) the structured form of coordination driven by extra-local organizations or programs aimed at fostering sustainable tourism development in rural villages such as “Borghi più belli d’Italia”, “Borghi autentici” and “Bandiere arancioni” (in Italy) and “Pueblos turísticos” in Argentina. From a methodological perspective, the above-mentioned issues have eventually developed into key concepts for the comparative description and analysis of the cases.

Focusing on the first issue—that is the social problem represented by the shortage of social capital as the main barrier to sustainable tourist development in most peripheral rural areas—this can be considered as a so called “adaptive problem” [1] (p. 38). Its characters in fact are not technically delimited and defined, but complex. Thus, its solution is not a predetermined one and can be addressed in different ways.

If on the one hand tourism is often recognized as an important driver of social change in peripheral rural areas, in terms of territorial revitalization [2,3] enhancement of the countryside resources [4,5] and heritage preservation [6], on the other one its management and governance are often very complex, mostly due to the fragile socio-economical structures of small rural communities. Within the Italian context, the ageing and declining population, the inadequacy of social services, as well as spatial peripheralization [7,8] and the crisis of traditional local economies have led to a spiraling-down effect, thus limiting the economic potential of the contemporary rural tourism demand. Similarly, within the Argentinian context, rural areas often highlight a twofold kind of problem. First, the small and family farming shows a structural weakness due to an oligopolistic and oligopsonistic context which limits its capacity of investment and diversification [9]. Second, the growth of rural tourism has often led to the making of “tourist enclaves”, characterized by the folklorization of local identities and the commodification of cultures, instead of favoring a place-based rural development [10].

As most scholars agree, the activation of the place-based resources in terms of tourist offer organization [11,12,13] and of sustainable local development [14,15] implies the involvement and the agency from a varied multiplicity of social actors, public institutions, and private companies. In peripheral rural contexts, however, these conditions are a problem by themselves, since the stakeholders may be lacking the right economic and political power as well as the motivation, the skills and the adequate social competence (such as cooperative learning and working) needed to address the complexity of change. Nor a single entity or actor or association by itself has the power to favor the necessary change, because these social problems show an interdependent nature, which is tightly related to the different social and historical contexts and to a specific social arena. That means that the consequences of any action may be unpredictable and that many outcomes may not be easily forecasted. Social change in fact is usually a consequence of a gradual improvement of an entire system rather than a single and sudden innovation. According to the stakeholders’ perception, rural tourism—more than other socio-economic fields—has showed the growing importance of cultural and institutional factors in economics dynamics [16]. The most influential way to address any adaptive problem and transition is then to trigger and manage a co-evolutive process [17] that supports the mobilization of as many organizations and actors as possible, both on a local and a wider level. Especially in the field of tourism, this is a shift that implies the importance of an approach focused on “community-based tourism” (CBT) [18,19]. Such a shift would include communities’ awareness raising in understanding their situation, their need to take actions, to participate and to make decisions.

This latter aspect—concerning in particular the importance of local communities’ participation and collaboration in the transition towards sustainable tourism—is closely associated with the second issue proposed in the paper, based on the definition of “collective impact”, that is the commitment of actors from different sectors to the common agenda of rural tourist development. Based on this topic, it is here assumed that tourism development can be set in a sustainable way only if it is perceived as a mutual goal within a community and among the different stakeholders [18]. This assumption takes into consideration two different aspects. First, the integration among the different assets shaping the so called “countryside capital” [5]; second, the commitment of social and economic actors operating in different fields. Different actors in fact possess and manage the specific assets that need to be pooled to make the process of tourist enhancement possible. By the way, Garrod et al. [5] write about a necessary re-conceptualizing of the place-based rural resources to achieve a higher profile of rural tourism, in terms of sustainability and interdependence with natural/cultural heritages. This means to re-cast the place-based resources as “capital assets”, that can be invested in and from which some social and economic benefits may be drawn, provided that the assets base is not overstretched by the demand.

Essentially, it can be stated that a place-based rural tourism development is composed of three main assets [5]: the naturalistic one (related to environmental resources and wildlife), the built one (related to rural settlement) and the socio-cultural and economic one (related to agricultural systems and other economic sectors, local identities, and cultures). Based on this conceptualization, social and economic rural development may be favored when the hospitality system is interconnected with the activation of the countryside capital. At the same time, the integration and intertwining among the available assets is made possible by the multifunctionality of local businesses which have to carry on different functions concerning not only agriculture but also the security and quality of food, the management of hospitality, the landscape and biodiversity conservation [20], the safeguard of water and other natural resources, the vitality of local cultural heritage. Therefore, integration, commitment and multifunctionality, rather than being features concerning single farms/enterprises, have to do with the agricultural and tourist system as a whole, characterizing a certain rural area or region [12].

According to such a view, rural tourism has a sense in terms of local sustainable development, when it becomes a set of “common-pool resources” [12] (pp. 9–12). That is, a capital that is “consumed” as if it were a public good and “produced” also through the private and public initiatives from different individual actors who are willing to cooperate. Therefore, rural tourism is a resource because it allows to obtain benefits (which would not be achievable otherwise) and to render additional value, and it is common-pool because it is not completely private, involving several producers and stakeholders coming from different fields of action. Such a framework stresses the fact that rural villages and their tourist enhancement are socially constructed and embedded in a specific set of institutions.

Against this background and based on the process of social innovation suggested by Neumeier [21], it could be assumed that the challenges arising from new tourists’ interests towards rural and sustainable experiences [22] represent an “initial impetus” that may lead an initial group of local actors seeking solutions and ideas able to address the perceived opportunities. The existence of such a stimulus is paramount as it is unlikely that actors will decide to cooperate without a common cause. Over the time, other actors may come and join the core group as they see some kind of either material or immaterial advantage in participating. These actors may be at the same time internal and external to the local community. In any case, the wider is the networking process activated [23], the stronger is the intertwining among actors, the higher is the level of coordination required.

This reasoning eventually leads to consider as important as the above two issues the third one, that is the structured form of coordination driven by extra-local organizations or programs aimed at fostering sustainable tourism in rural villages. The affiliation to at least one of these extra-local institutions has been the main pre-condition the authors used to select cases within the research design. This variable is paramount because it draws attention to the importance of networking and coordination also at levels wider than the local one. Within rural development, social innovation and change are closely related to the emergence of new collective learning and coordination processes, which take place not only on a locally based level but also involve outside participants [21,24]. These latter in particular are committed to foster bridging social capital among different territories. Such a process, while widening relations and partnership outside single villages, eventually results in a clear improvement for the single villages themselves. These external entities (whether a club as the Italian “Borghi più belli d’Italia” or a public support program as the Argentinian “Pueblos turísticos”) are here considered as “backbone support organizations” [1], since they offer an important infrastructure, which can plan, manage and support the local initiatives on a national level through ongoing planning, communication and facilitation.

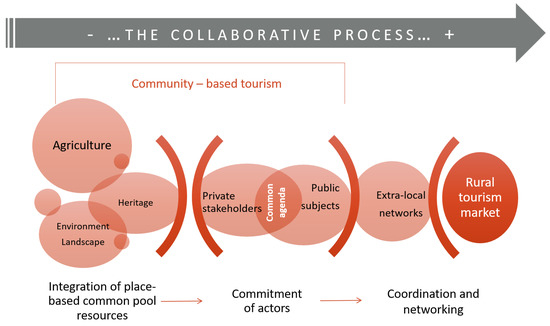

The mobilization of local assets on an endogenous level from one side, the partnerships with national organization/clubs/programs from the other, show that the power of collective action rather than coming from the number of participants is instead related to a multi-level coordination of the activities, through a mutually reinforcing plan of action [1]. As a matter of fact, an innovative and vital rural society implies the nurturing of both local and extra-local resources for the alignment of different groups and contexts towards a common agenda (see Figure 1 for a synthetic overview of the theoretical framework).

Figure 1.

Collaborative process within rural tourism: a theoretical framework. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

These processes open the way to the definition of a new approach to rural development which Bock [24] defines as “nexogenous”. Based on the importance of binding together forces and institutions within and across space, this approach is intended to underline the importance of relations (nexus in Latin) beyond either endogenous or exogenous perspectives. The linkage and coordination coming from extra-local institutions give access to exogenous resources, which may favor revitalization when integrated with the endogenous ones.

Against this background, this paper is intended to integrate the above collaborative ongoing processes with a system of measurement and assessment related to the levels of integration (among resources), of commitments (among local actors) and of coordination (between CBT and extra-local organizations). As highlighted by the multiple-case-study research presented here, what is really lacking is a shared model of processes measurement. A lot of projects and programs aimed at the tourist enhancement of rural villages have been carried on so far, both across Europe and in Argentina. Presumably, most of them have applied both CBT, collaborative nexogenous approach and social innovation, whose principles are shareable within the collective impact framework. Nevertheless, a shared system of measurement of the processes and of the goals has not been clearly structured yet. Based on this necessity, as well as on the definition of “collective impact” the paper tries and infers some variables that can be observed and eventually measured over the time.

2. Methodological Notes

The research here presented has been conducted within the methodological framework of a multiple-case-study research design. The choice towards this kind of method is related to several aspects. First, the case study is particular suitable to study and explore new and complex phenomena, being its nature mainly descriptive and explorative [25]. Second, it is a flexible method whose objectives can be easily re-oriented while the research is on progress and can refer to different data sources, depending on the singular situation to observe [26,27]. Third, it draws attention on the context and it fits those situations in which the boundaries between the studied phenomenon and the context are not clearly evident.

Therefore, each case is an exploration of a bounded complex system through a detailed and in-depth data collection which involves multiple sources of information. The multiple-case-study type in particular allows the researchers to gradually move from particularity to a certain level of generalization. If on a first step each case is analyzed and studied in its specificity, on a second step the comparison among a wider number of cases allows to get to a broader comprehension of the phenomenon [28]. Thanks to this kind of methodological approach, the research has taken into account both the differences among the single cases and the similarities. Furthermore, the multiple-case-study research design is particularly suitable when following an inductive approach. The choice of different cases grounded on the same research objectives may meaningfully help point out the different conditions the theoretical framework is based on. The methodology of multiple case studies has already been used in other contexts to study differences and similarities helping define tourism in rural areas, such as in peripheral Europe [29] and in South Africa [30].

In this research, data and information have been collected through different qualitative research techniques, such as field work, direct observation, and non-standard interviews to key informants. Secondary data such as official statistics and documents have been used too.

The cases have been selected according to a theoretical sampling. That is, according to meaningfulness of the theoretical categories [25] and not based on a statistical representativeness. Therefore, with special concern to the theoretical framework, the cases have been chosen when fitting the following variables and conditions:

- -

- small dimensions and peripherality of the rural villages compared to big cities;

- -

- presence of a (more or less) integrated system of tourist offer at community level, able to include other economic activities; and

- -

- presence of public policies and/or institutions at extra-local level aimed at promoting complex development programs and at activating processes of network building and social innovation for rural tourism development.

Within each case, particular attention has been drawn on the description and the analysis of different aspects tightly related to the main theoretical issues addressed along the paper. Besides the data concerning the social structure of the villages (mainly quantitative) other important qualitative data related to the ongoing social processes have been taken into account. These aspects include the enhancement of the different local assets and the countryside capital, the integration between different place-based resources and economic sectors, the commitment of actors within processes of CBT, the networking processes and the partnerships linking the local level to the regional/national one.

During the analysis, a monitoring sheet has been used to rationalize the data. Therefore, the information collected in each case study have been synthesized in a set of indicators extrapolated from the theoretical framework (see Figure 1). In particular, the following dimensions are taken into account:

- (1)

- Integration of the resources. CBT is pursued on a set of place-based common-pool resources such as agriculture, heritage, environment, landscape, traditional food products, handicraft. The level of integration of these resources could be measured by the following indicators: (a) the number of the different assets involved and (b) the presence of formal elements of integration among the resources, such as collective trademarks.

- (2)

- Commitment of the actors. This aspect takes into consideration the existing relations among private stakeholders, the commitment of local institutions in the building of the tourist offer, the occurrence of meetings and activities leading to the definition and continuous upgrading of a common agenda, the coordination, and the degree of relationships formalization. The level of commitment is here measured by (c) the level of community involvement (d) the level of public commitment (e) the existence of public-private partnerships (f) the definition of a common agenda (g) the existence of formal organizations among actors.

- (3)

- Coordination and level of networking. Local actors’ organizations operate within networks acting at both territorial and extra-local levels. The level of coordination is measured by (h) the existence of backbone supporting organizations (i) the level of networking at extra-local level (l) the level of local actors’ involvement in the activities promoted by extra-local networks for tourism development (promotion, branding, local actors’ empowerment, developing of innovation processes, organization of events, market orientation and products selling).

Finally, each indicator has been assigned with a specific value (see Table 1). To make the measurement system as simple as possible, all the variables values are comprised between 0 and 1 and are assigned the same weight. Clearly, since it proposes the assessment and measure of complex and qualitative processes rather than the impact of a single intervention, the model suggested cannot help to be widely based on the researchers’ discretion.

Table 1.

List of variables identifying collaborative processes and calculation methods.

The sum of the single values has contributed to set each village on a Cartesian plan where the x-axis represents the “integration” dimension and the y-axis the “coordination”.

3. The Argentinian Context

3.1. Rural Development and Rural Tourism Issues

Rural tourism is particularly interesting in the Argentinian context, because both of its relevant growth in the last few years [31] and of its role within mainstream tourism diversification and rural local development. For these reasons, it has recently drawn attention from public policies making.

One of the main characteristics of Argentinian rural regions is heterogeneity, partly due to the complex processes of an unbalanced development that, while benefitting the central area of the country (the Pampas region, along with the most important economic players and the export-oriented primary sector) have weakened the rural economies and populations of more peripheral provinces such Patagonia, Northern and Western Argentina (for further analysis of regional development in Argentina see: [9,32,33,34,35]).

The main problems concerning rural development in these provinces are (following [9]):

- structural weaknesses of public policies in favoring the land ownership by small and family farmers;

- an unequal distribution system managed by intermediaries, processing industries and exporters, which impede small farmers to reach an adequate standard of living and sufficient capitalization;

- low productive diversification, due to both cultural reasons and insufficient resources;

- the small dimension of farms;

- difficulties of small farmers in obtaining credit; and

- capital concentration and extra-regional provenance of the capital.

Other issues to be added are the expansion of extractive processes like the big scale soy production, the mega-projects in mining and the hydrocarbon exploitations. These processes are often associated with speculative and financial capital [9] and sometimes generate conflicts with the rural communities.

In the central region of the country—the Pampas region, whose main part is constituted by the Province of Buenos Aires—two further issues emerge. First, in the fruit and vegetables districts located near the big urban areas, small producers must face similar problems than in the other rural areas of the country, but they are worsened by the land competition for urban uses. Second, in all the other areas, which are characterized by export-oriented cultivations (soy, corn, wheat, sunflowers), the growth of the “technology packages” for farming generates the so called “green desert” or an “agriculture without farmers”.

These processes, which emerged in the 1990s, have become more acute in the present century [36], and have provoked a strong impact on the economic and demographic structures of rural villages, getting to a deeper peripheralization process. Furthermore, the dismantling of the railway system which used to connect rural areas with the main urban centers made the situation even worse.

All these situations have contributed to weaken the small and family farmers in producing an adequate added value. Furthermore, their conditions are sometimes made even more critical because of the oligopolistic and oligopsonistic context in which they work, characterized by big economic groups and insufficiency or ineffectiveness of public policies.

By the way, Manzanal et al. [37], rather than pointing at the public policies failure in sustaining farmers’ capitalization and economic development, focus on the development model itself and on the power and political structures which characterize this model. According to such a perspective, some possibilities may emerge for actions and strategies aimed at finding some development chances for the lower-income local actors in the cracks of dominant actors’ strategies. This does not suppose a change in the structural conditions but rather the search for different and alternative development paths.

In the framework of the “new-developmentalist” policies implemented in the country between 2003 and 2015, various strategic programs were elaborated with the aim of enhancing local rural development. In particular, the INTA (Instituto de Tecnología Agropecuaria) implemented projects aimed at reinforcing small producers and diversifying rural production. Its interventions focus on the processes, through the direct involvement and empowerment of local actors. This is thought to reinforce the socio-institutional network and the local economic system, with the final aim of improving rural communities’ quality of life. It implies an integrated approach to rural environment which links the economic, socio-cultural, political-institutional, and environmental aspects into one single framework [38].

Within these proposals, rural tourism is considered to be a means for the revitalization of small rural economies. Tourism in fact may facilitate productive diversification and promote practices based on the cooperation and interchange among actors, as well as on cooperation at different institutional levels, including public-private partnerships.

This comprehensive perspective is however in contrast with already existing numerous entrepreneurial investments in rural tourism, which have operated in a logic of tourist “enclaves”, by “putting on stage” [39] a stereotyped idea of what the authentic Argentinian culture is meant to be. This has actually led to a deep process of “touristification” [40] that has come to undermine local arenas, finally commodifying local identity and culture.

Considering these issues, the collaborative process proposed by the collective impact approach may assume a great importance for enhancing tourism development in rural villages. In several villages of the Buenos Aires province, for example, the attention towards tourist activities has grown as tourism has been considered a solution for these multiple development issues: as a way out of the economic crisis which followed the dismantling of the whole railway Argentinian system or as an option of economic diversification, combining tourism with local productive activities, mainly agriculture and food processing. According to such a view, different public authorities at national, provincial, and municipal level have developed programs aimed at strengthening tourism in rural villages as a potential development alternative. Among these, the program “Pueblos Turísticos” (Tourist Villages) that has been developed by the Buenos Aires province through the Tourism Department (Subsecretaría de Turismo) can be certainly considered as one of the most important.

3.2. The Program “Pueblos Turísticos”

Tourism in Argentina has showed a relevant growth since 2003, initially favored by the depreciation of the exchange rate but sustained in the different regions by the combination of natural resources, cultural attractions and a significant hotels and services equipment. Argentina is classified as the second international tourist destination in Latin America, after México and as the first in South America with 6.71 million tourist arrivals [41]. Considering domestic tourism, 54.08 million visitors were counted in 2017, of which 30.37 million tourists and 23.71 million daily travelers. Between 2006 and 2017 a significant growth was registered: tourists increased by 48.5% and daily travelers by 36.2% [42]. Between daily visitors, leisure travelers moved from 60.3 in 2006 to 67.0% in 2012. In the case of tourists, the increase in those from abroad stands out: in 2006, they represented 7%, while in 2017 they represented 13.6% [42]. The visit to rural areas is among the main non-traditional destinations for daily travelers and internal tourists: in the first half of 2018 they received 618,000 hikers and 329,000 tourists.

The internal region of the Buenos Aires province is the area with the highest number of daily visitors and tourists (48.0%) [42], mainly coming from de metropolitan region of Buenos Aires. Furthermore, the region showed a growth of daily visitors and short-term tourists higher than the national average, increasing its market share from 29.8% in 2006 to 40.0% in 2014 [31].

This tourism growth has been accompanied by some public policies supporting the development and the promotion of tourist destinations at different institutional levels, through general programs and specific actions. The “Rural Tourism Program” was promoted in the year 2000 by a conjoint intervention of the Tourism Direction and the Agriculture one at national level and it was the most effective in promoting new rural tourism. Within the program different projects were considered, such as the “Municipio Rural Turístico” (Rural Tourist Municipality) and the “Rutas Alimentarias Argentinas” (Argentinian Food Roots) [43].

At the same time, also the Buenos Aires province approved a specific law (Ley Provincial de Turismo 14,209/10) aimed at promoting different issues in this field, according to an integrated approach to tourist development.

The Tourism Department is in charge of implementing the law objectives through different programs. Among them, the program “Pueblos Turísticos” started in 2008, with the aim of promoting the development of small villages of the province through the integration of tourism in the existing activities. The objective was the enhancement of the opportunities for local producers and the encouragement of sustainable tourism activities able to support local identity, employment, genuine resources. Directly related to tourism is the real or potential integration within the local and regional production chains, able to provide goods and services. In this sense, the aims of the program are coherent with the literature on rural tourism [5,44,45,46,47,48].

The program supports small rural villages (less than 2000 inhabitants) which have already exploited or potential tourist attractions and which have expressed their willingness to develop tourist activities and undertakings. It is composed by five sub-programs coordinated in a unique development strategy aimed at strengthening the tourist proposals: Relevar (relieving), Capacitar (empowering), Desarrollar (developing), Promocionar (promoting) and Integrar (integrating). Each sub-program is composed by planned, concrete and measurable actions. Among them, the following ones can be mentioned: the local producers’ empowerment managed by specialists, the tourist signage, the village promotion at local and extra-local scale through different media, the financing of tourist infrastructures for the villages and of the equipment for tourist undertakings. In 2017, 23 villages were part of the program, characterized by different levels of development and program implementation, among them Uribelarrea and Carlos Keen, considered as case studies in this comparative research.

4. The Italian Context

4.1. Rural Tourism and Rural Villages Development Issues in Italy

As a growing phenomenon, Italian rural tourism is receiving larger and larger attention by media and consumers. It is nowadays characterized by a significant growth both on the offer and the demand side and, at the same time, by profound and rapid changes, thus becoming a complex and articulated phenomenon, as such of difficult definition and quantification [44].

Following a generally accepted classification, rural tourism includes the different tourist activities which take place in rural localities, in connection with the place-based resources and where rural culture plays an important role. The rural resources can be interpreted as such from a strict to a broader sense. In a strict sense, they are primarily related to agriculture and agricultural products processing, whereas in a broader sense they would also refer to environmental and protected areas resources, cultural and architectural heritage of the rural villages and the small towns in rural areas.

Rural tourism can therefore be considered as an “umbrella word”, including different tourist products such as agritourism [49,50], slow tourism [51], tourism in rural villages, ecotourism [52], wine and food tourism [53]. At the same time, it can be described as a transversal sector able to activate mechanism of economic and territorial regeneration in rural areas [5].

The strictest relation between agriculture and tourism is represented in Italy by the agritourism phenomenon, defined as a whole complex of diversified activities (leisure and experience in farm-work) and tourist facilities (catering, accommodation, food processing and selling) managed by farmers through the use of multifunctionality [54,55]. The number of agritourist farms in Italy grew constantly in the last ten years, from 17,720 in 2000 to 23,406 in 2017, with a growth rate of 32.1%. In the same period, the growth of beds was 40.7% and the number of nights moved from 8.2 to 12.7 million (+54.1%), generating an economic value of 1.36 billion euros [56].

Within the same period, the municipalities with an agritourist offer grew from 4259 to 4893 (+14.9%). Taken that 5702 municipalities in Italy (70% of the total) count less than 5000 inhabitants, it emerges the importance that this kind of tourist offer can have in the ongoing changes within tourism trends.

Moving towards a broader concept of rural tourism, different market researches consider food and wine tourism as the first travel motivation for Italian and foreign tourists. It is recognized as the main motivation from the 22.3% of Italian tourists and the 29.9% of foreign ones [53]. In 2017, the total expenditure for food products was about 17 billion euros (15% of the total tourist expenditure).

Due to the polycentric structure of Italian territory, characterized by a network of medium-sized urban centers at regional or sub-regional level, it is not possible to provide a unique classification of rural municipalities. A useful concept to approximate the rural condition could be peripherality, meant as the distance to the main service-providers centers. Adopting this definition, 1884 municipalities could be classified as peripheral and ultra-peripheral, with a population of about 4.6 million people and an average of 2438 inhabitants per municipality.

This category performed a meaningful growth in tourist accommodation, both in the number of establishments and in beds, especially within the “non-hotel” sector, including agritourist farms and bed and breakfasts (B&Bs). Also, the number of municipalities providing accommodations has increased.

Considering the time lapse from 2003 to 2012, in these municipalities the tourist function index (beds per inhabitant) increased, both for ultra-peripheral (from 38 to 41%) and peripheral (from 16 to 18%) municipalities. Moreover, it is much higher than the national average (8%). At the same time, the number of agritourist farms and B&Bs moved from 9 to 24% of the total in ultra-peripheral areas and from 10 to 25% in peripheral ones.

Based on the downgrading of mainstream tourism from one side and on the spread of new motivations for tourist choices from the other, these data seem to confirm the development of a process that could be defined as “tourism transition”. This ongoing process is leading to a new perception of peripheries, a divergent conceptualization of remoteness, and a meaningful reorganization of the tourist supply in rural areas [3].

On the contrary, the demographic dynamics in peripheral areas were still negative. The average population growth rate was −1.1% in ultra-peripheral municipalities and −1.8% in peripheral ones, with two thirds of the municipalities affected by a decrease in population. In about one out of three villages the population decrease was higher than 10%, whereas in one out of ten the decrease was higher than 20%. Furthermore, almost half of the peripheral areas witnessed a simultaneous population decrease and an increase in the number of beds in regulated tourist establishments.

Nevertheless, the role of tourism in ultimately modifying the demographic trends and the capacity of rural communities in addressing the opportunities coming from the ongoing tourism transition is still questionable [3].

4.2. National Initiatives for the Tourist Development of Rural Villages

Since late 1990s, “rural villages tourism” in Italy has constantly developed, becoming almost an autonomous phenomenon. It has drawn particular attention on the historical and architectonic heritage of small peripheral municipalities as well as on their food and wine productions. Over the time this kind of experience has been institutionalized through several specific activities aimed at safeguarding a heritage at risk of abandonment due to emigration flows from inner areas to big cities. This objective has been pursued also by some nationwide associations and projects working on promoting a high-quality tourist product in these marginalized contexts. In particular, three different initiatives (Bandiere arancioni, Borghi più belli d’Italia, Borghi Autentici d’Italia) have developed in this field, with each one stressing specific characteristics. The three Italian case studies have been chosen because belonging to one of these associations.

The “Bandiere Arancioni” (“Orange Flags”), a sort of spin-off of the Touring Club Association was the first initiative to develop. It is a tourist-environmental seal of quality and it was born in 1998. This association recognizes a symbolic orange flag to those municipalities that—given the minimum requirements of being situated in an inner area and of not exceeding the number of 15,000 inhabitants—undertake to reinforce their commitment in local development actions aimed at:

- Enhancing cultural local heritage

- Safeguarding the environment

- Promoting hospitality and high-quality accommodation and restaurants

- Revitalizing handicrafts and regional food productions.

The seal is granted following the application from the municipality and a blinded visit and assessment from the association operators who must evaluate the request based on a complex model of territorial analysis. The model takes into consideration more than 250 variables grouped in five different macro-areas (hosting, accommodation and facilities, tourist attractions, environmental quality, overall quality of the village). These quality standards must not be easy to be satisfied, considering that only 9% of the applications are successful in obtaining the orange flag. At the end of 2016 only 220 orange flags were actually granted out of 1786 applications.

Three years after the Touring Club, also the National Association of Italian Municipalities promoted its own initiative for the tourist development of small rural villages and founded the Club “Borghi più belli d’Italia” (“The most beautiful villages in Italy”). Also in this case, the affiliation to the club follows the municipalities’ self-candidacy. Besides some minimum requirements (such as an overall municipality population not exceeding 15,000 residents with no more than 200 living within the old hamlet), the village must have a still well preserved and certified architectonic and environmental heritage. Once the club has granted the award, the municipality has to endorse an agreement aimed at realizing concrete actions of sustainable development such as traffic restricted areas, good care of public green areas, handicrafts and agriculture revivification, organization of tourist tours, organization of high-quality cultural events. The present members of the club are 268 all over the Italian regions.

A separate discourse needs to be entered into for the non-profit association “Borghi Autentici d’Italia” (“Authentic villages in Italy”), founded in 2002. Differently from the two initiatives mentioned above, the title of “authentic village” is different from a tourist brand. Admission to the association does not happen following an application process to be valued for a possible recognition. Instead, it is open to all those municipalities that (satisfying the basic requirements of a population not exceeding 15,000 residents and with an historical valued architectural heritage) declare their commitment to share some important principles related to sustainable development. In fact, to become a member of “Borghi Autentici” means to get engaged in a specific enhancement process, aimed at the sustainable promotion of local cultural identities, at the revitalization of the traditional productive systems, at the restoration and urban redevelopment of the old town, at the improvement of the quality of life for both residents and guests, at the protection of the natural environment, at the strengthening of the active participation from the citizens and at the consolidation of integration and cooperation policies. The tools the association uses to pursue these objectives are “The Code of Ethics and Social Responsibility of the National System of Authentic Villages of Italy”, the “Charter of Quality of Authentic Villages” and the “Charter of Principles”. To accompany and support this path, the association provides its own free technical assistance and has an ethical fund dedicated to all the members. Through the submission to specific calls, municipalities can be funded for the realization of projects and interventions focused on the promotion and the enhancement of both tangible and intangible assets related to the local heritage. The association is currently composed of 189 member villages.

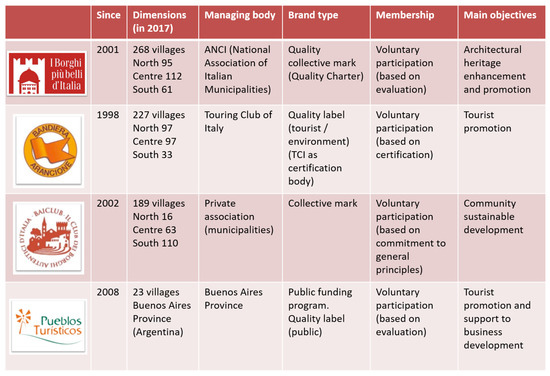

For a synthetic overview of the different Italian and Argentinian initiatives see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Main aspects of tourist rural villages brands. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

5. The Case Studies

5.1. The Argentinian Case Studies

The geographical position of the selected Argentinian case studies is pointed out in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tourist Villages in Buenos Aires province: localization of the case studies. Source: authors’ elaboration from Google Maps.

5.1.1. Uribelarrea

General description. Uribelarrea is a village of the Cañuelas municipality, situated on the borders between the Metropolitan Region of Buenos Aires and the inner rural region of the Buenos Aires province. Uribelarrea village counts with 1300 inhabitants.

In the past, the village was part of an important milk production district, directly connected with the city of Buenos Aires by railways. In the 1990s, the increasing concentration in the milk-producing sector, along with the dismantling of the whole railway Argentinian system, caused the crisis of the small-scale production and distribution, as well as the disappearance of milk-producing and processing firms. This productive change provoked a process of peripheralization of the village, the decline of the rural-urban relations and a strong population decrease. Only during the last years, a growth in the demand of holiday homes by the medium-high class urban population developed a renewed interest for rural areas. New residents were also attracted by the opportunity of new entrepreneurial activities related to this trend.

Integration between place-based resources and commitment of actors. At the moment, livestock farming and artisanal production of different food products (such as cheese, salami, sweets, wine, beer) have developed, mainly oriented to the direct sale to daily visitors through the presence of food establishments. The old railway station has been reconverted into an ethnographic museum focused on the history of the milk production in the village.

Some actors more than others have played a strategic role in this reconversion of the production system. In particular, the presence of the agro-technic school “Don Bosco” contributed to the spread of competences in the food processing sector, to the attractiveness of students from all over the province and to the establishment of new farms and food enterprises by the graduates. “Most students have started their own transformation activity once finished their agricultural studies”—as the Director of Studies of the school said. It represents itself a tourist attraction with his selling point of food products.

Networking and coordination. The organization of the tourist offer is managed by two main institutions: the Tourism Direction of the Municipality (in the public sector) and the Tourist Association Uribellarea (in the private one). The latter involves most local economical actors and promotes a local collective brand: “Uribe pueblo natural” (Uribe natural village), aiming at positioning the village products in the market and at connecting food production with tourist services and commercial activities. At the same time, the association co-organizes with the Tourism Direction a very popular folk food festival, la “Fiesta Nacional de la Picada y la Cerveza”. The Tourism Direction promotes food and cultural itineraries linking the different villages of the municipality into a common tourist product. The Tourism Direction acts also as backbone supporting organization, offering organizational support and leading the private actors’ choices.

Both the presence of the school graduates and of new residents have led to a mixed composition of the local entrepreneurship, composed by both long-term residents and new ones. The association has contributed to mitigate conflicts and to promote integration among traditional and new activities, leading the actors towards a common agenda.

Finally, the opportunity to join the “Pueblos turísticos” program has empowered these dynamics, thanks to the technical assistance, the operators training, the branding at national level and the financial support for the creation of new enterprises offered by the program.

These activities are mutually reinforcing. At the same time, they reinforce the conditions that enabled the reconversion of the village towards a food tourism destination, as a place with a multiplicity of actors with different trajectories but mutually connected within a cross sectors coordination involving cultural and recreational activities, production, tasting and selling of local food products.

5.1.2. Carlos Keen

General description. Carlos Keen is a village of the Luján municipality, situated at the north-east of Buenos Aires province, at 83 km from the city of Buenos Aires. The village counts with 557 inhabitants and with an average number of around 1500 visitors during the weekends. Tourism started in the second half of the 1990s and developed in the first decade of 2000, oriented to the leisure of middle-high class of the urban population. The development of tourist activities led to the establishing of accommodation structures and the building of numerous holiday homes by the inhabitants of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires.

Integration between place-based resources and commitment of actors. The main driver of Carlos Keen attractiveness is gastronomy, with 14 restaurants offering mainly traditional but also gourmet menus. The offer is complemented by recreational activities, green spaces, a rural open-air museum, and a multi-services building (including a small theatre, a temporary exhibition area, a tourist information office) obtained by the reconversion of the old barn of the abandoned train station. Other recreational and sport activities are offered directly on the farms and in the country clubs situated in the area. Agriculture activities, such as breeding, eggs production and vegetables cultivation, have been developed in connection with the gastronomical offer, as well as food processing. Different goods are produced, such as wine, sweets, pasta, honey, cheese, salami, jam, preserved vegetables and mushrooms and liquors. Handicraft products are also realized and sold in the specialized shops of the village. Similarly to Uribellarea, also in Carlos Keen it is possible to find food products realized in other villages belonging to the program Pueblos Turísticos. A familiar entrepreneurial model could be observed, with pluri-activities and diversification which integrate tourist offer with food and handicraft production or other services.

Networking and coordination. Carlos Keen was accepted in the program “Pueblos Turísticos” in 2008, when it was already popular as a gastronomic destination and had already received other national recognitions (it was awarded with the title of Historic Village in 2003 and of National Historic Site in 2006). In its first stage, the program implementation was accompanied by a strong participation of the whole local community, with the creation in 2010 of the Community Tourism Association (CTA), the implementation of signage and training courses management. In particular, the CTA has taken on an important organizational role. It was founded with the specific aim of organizing and managing the tourist development of the village, thanks to the commitment from different subjects (mainly the Luján municipality and the Tourism Department of the Province—through the program Pueblos Turísticos—but also the Center of Territorial and Environmental Research of Buenos Aires) [57].

At a later stage, a twofold attitude emerged. On one side extra-local actors with investments in the village—but with a reduced involvement in the community—showed a slowing-down interest. On the other side instead, the inhabitants with entrepreneurial activities maintained their engagement in a collective work for carrying on a common tourist project [58,59].

In short, over the time the program has broadened the external visibility of the village, but a certain level of criticism has remained unaddressed. For example, the tourism-oriented education is still insufficient, private investments by local actors are low, the foundational architectural heritage still deteriorates [59]. Against this situation, it is clear that—despite a quite successful combination and integration of resources at tourist purposes—the growth of tourism is not related to a shared common agenda yet. It is rather the result of the convergence of different actors’ personal interests. The lack of commitment towards the village’s sake constraint the efficiency of the CTA, which must limit its activities in promotion and collective procurement of intermediate goods.

5.2. The Italian Case Studies

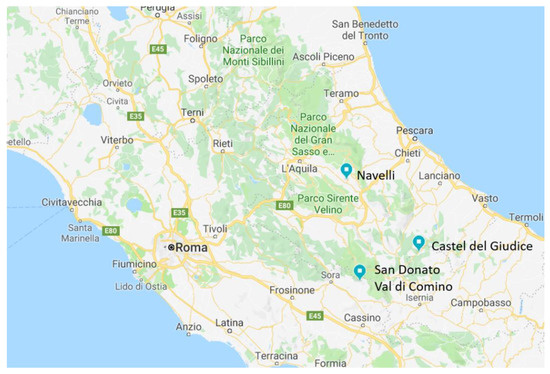

The geographical position of the selected Italian case studies is pointed out in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Rural villages in Italy: localization of the case studies. Source: authors’ elaboration from Google Maps.

5.2.1. San Donato Val Di Comino

General description. San Donato Val di Comino is a municipality of 2076 inhabitants in the Lazio region, in central Italy, at a distance of about 140 km from Rome. The village is in the Apennines mountains, at 721 m above sea level, in an agricultural area and in the buffer zone of an important national protected area (the National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise). Because of the quality of its architectural heritage and natural environment, the village has been rewarded with the orange flag and inserted in this network. Nevertheless, tourist accommodation sector is not highly developed, and the main economic activities are agriculture (olive oil and beans production, sheep breeding) and agritourism.

Integration between place-based resources and commitment of actors. The agricultural sector is structured and organized at district level (Comino Valley), with the presence of various collective organizations. There are an organic producers’ association called “Val Comino Bio”, which has gathered about 80 producers in the valley, two Protected Designations of Origin (PDOs) consortia (pecorino cheese and beans) and a secondary agricultural school. A new generation of young farmers—whose start-ups have been in many cases supported by the EU rural development policies—contributed to this new role of agriculture. “A 30-year-old generation decided to stay and they could make this choice thanks to agriculture”—the Mayor of the town said. The architectural heritage of the old hamlet is well preserved even if underused because of the great number of second-homes which make the actual resident population very weak. This phenomenon is mostly related to the high emigration process towards Rome that characterized the valley in late 20th Century.

Networking and coordination. Public authorities tried to lead the organization process of the economic activities, even if this kind of commitment has not been so successful so far. According to the key informants’ point of view, this would be partly due to the lack of entrepreneurial orientation. “I prefer cooperating with the operators living in the same territory where I live, at least with those I share ideas with. Top down initiatives have often been useless”—one of the interviewees agritourist farmers stated. Because of these reasons, the tourist sector remains far from developing fully its potential. Despite this weakness of CBT processes, there is an important willingness to coordinate the public interventions at district level (represented by a Local Action Group, the Municipality Union, the National Park authority) and to cooperate with national organizations. The municipality is also part of the Italian Association of Organic Cities and the Association “I Borghi più belli d’Italia”.

5.2.2. Navelli

General description. Navelli is a municipality of 562 inhabitants (2017) in the Abruzzo region, in central Italy. The village is in a wide plateau at 760 m above sea level surrounded by the Apennines mountains, at the feet of the Gran Sasso peak. Because of its old hamlet historical-architectural value, and the natural environment, the village was admitted in the Club “I Borghi più belli d’Italia”.

Integration between place-based resources and commitment of actors. Because of the strong depopulation process which characterized the village in the second half of the 20th Century, agriculture is mainly managed by elderly people and mainly oriented to satisfy local markets. Only recently a repositioning towards tourism has been registered, mainly by non-local people (sometimes new residents) who have showed an interest in reusing the ancient buildings as accommodation structures (mostly B&B, and tourist apartments). Various attempts have now being made to contrast agricultural decline and given new value to the regional products: the territory of Navelli is part the PDO Zafferano dell’Aquila (L’Aquila saffron) and chickpeas producers are now associated in a Slow Food Presidium.

Networking and coordination. The coordination process among actors is quite weak, both for the weakness of the business fabric and of the institutions

Here everyone is making his own business and they prefer to sell their products backroom […] Institutions should support stakeholders in their projects. It is not enough to obtain a trademark. If projects do not turn into actual practices and local actions they have no sense.(One of the young public administrators)

At the same time, the level of community commitment is quite low and almost entirely based on the motivation of a small core group of actors which often must manage a certain level of local conflict. Nevertheless, the Slow Food Presidia network and the PDO label could represent a strong branding and promotion opportunity, if adequately supported on the producers’ side and by the activation of some private/public partnerships.

5.2.3. Castel Del Giudice

General description. Castel del Giudice is a municipality of 329 inhabitants in the Molise region, in southern Italy. The village is in the Apennines mountains at 800 m above sea level. It is member of the association “Borghi autentici d’Italia”.

Integration between place-based resources and commitment of actors. In front of a real risk of disappearance of the local community, in 1999 the municipality started a process of revitalization of the village, trying to convert the critical elements (emigration and ageing of the population, abandonment of the buildings, closing of the primary school because of lack of children) in factors for success. The municipality was able to involve most of the inhabitants in this process. The school building was transformed in a care home managed by a public company (composed by the municipality and some inhabitants), an urban transformation company (public/private partnership for investment) was activated to reconvert the abandoned buildings into an “albergo diffuso” (a hotel consisting of houses located throughout the village), an agricultural company (“Melise”) with 75 associated (among the residents) was established for the cultivation and marketing of local varieties of apples, with the aim of preventing the agriculture abandonment.

The municipality has always activated processes. It has always found a solution to solve problems and realize projects. It has aimed at activating trust processes. […] if you want to realize such projects everyone ought to get involved […] you need to have a long-term vision, but you have to close things in the short terms. People need to see results soon, otherwise they keep living waiting for and losing hope in the future.(The Mayor)

Networking and coordination. The municipality is definitely the leading actor of a process aimed at supporting community-based development and tourism. During the last years, it directly looked for external subjects and resources to be involved in the process and it always favored networking, both within the village and in extra-local networks. Castel del Giudice is associated with different national organizations: the Italian Association of Organic Cities Slow Food, Italian Association of “virtuous” municipalities. The network with consuming markets is assured by the relationships with ethical purchasing groups. A community cooperative for the provision of services and agricultural labor force is the last ongoing initiative.

The territory has to be connected; it is absurd that a boy from Molise has to eat apples coming from Trentino; or that we have to sell our apples in Bologna. The supply chain ought to be closed locally; Thanks to networks we can sell our products at a national level. The products are already sold before being produced and that allows us to widen the offer.(Mayor’s statements)

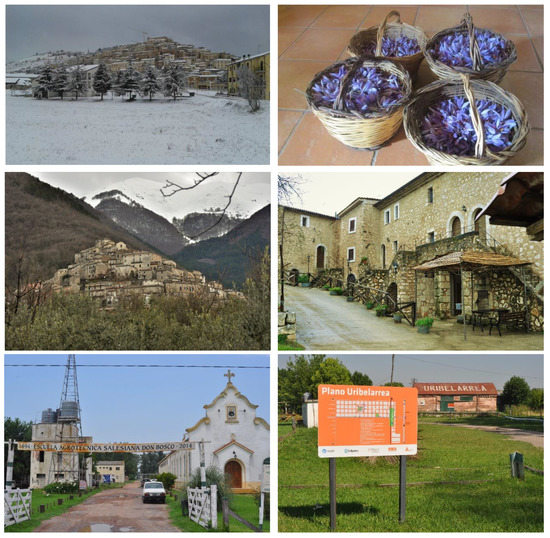

In Figure 5, some pictures of the selected Argentinian and Italian case studies are presented.

Figure 5.

Photos of the villages (from the top to the bottom): Navelli (winter view; saffron flowers); San Donato Val di Comino (view; agritourist building); Uribellarea (agro-technic school; ethnographic museum).

6. Discussion: A Synthetic Overview

Each case study here presented displays someway collaborative ongoing processes which give shape to a more or less integrated system of tourist offer at community level. This result is related to the activation of place-based resources and to the integration among different economic activities.

The commitment of local actors from different economic sectors, together with the presence of various collective organizations and the intervention of public authorities (in a direct way or through the definition of public/private partnerships) represent the main elements of the above analyzed collaborative processes.

The cases are characterized by a different level of networking and coordination between CBT and extra-local organizations. According to their level of complexity, these dynamics may favor the success of sustainable development programs, by activating processes of network building and social innovation through a “nexogenous” approach [24].

Based on these considerations, a model of measurement of these collaborative ongoing processes is proposed, using monitoring sheets and the measurement of the variables used to rationalize and analyze the collected data (see Table 1 in the Methodological notes).

Starting from the descriptive analysis, an attempt of assessment of the five case studies, is provided in Table 2. The sum of the variables summarizes the level reached by each analyzed village within the collaborative process.

Table 2.

Assessment of the presented case studies.

The variables can be summed up and positioned on a Cartesian plan, where the x-axis represents both the level of integration of the resources and the commitment of the local actors (that is the level of local community organization) and the y-axis the level of networking, from the local level towards the extra-local one.

Figure 6 describes the position of each village in a diagram considering the sum of the considered variables. The dimension of each point represents a qualitative evaluation of the amount of available place-based resources. The x-axis summarizes the level of integration, moving from fragmentation to integration of the initiatives (resources and actors). The y-axis instead represents the positioning from individual and isolated initiatives to coordination of actors and institutions on different networking levels. Starting from a given amount of place-based resources, each village could be positioned on a different combination of level of integration and coordination.

Figure 6.

A “qualitative measurement” of the collaboration process (% of the maximum score). The dimension of each point represents a qualitative evaluation of the amount of available place-based resources.

As synthetically represented in the diagram, each village (the points in the plane) shows a different size due to the amount of available local assets. The Italian village of Navelli, for example, is the biggest point. Nevertheless, its position on the plane is among the lowest ones, due to its low scores both on the integration axis (2.75) and on the coordination one (1). On the one hand, the lack of community involvement and of a common agenda, on the other the weakness in networking activities and coordination (related to an only formal membership) leave as strongly unexpressed and latent the potential value of the abundant local assets.

On the opposite, the Italian village of Castel del Giudice, even if showing the smallest size of the point, is set on the highest level of both axes. The full commitment of local actors as well as an advanced participation within the networking process have allowed the village to successfully activate its own available heritage.

7. Conclusions

During the last two decades, rural villages have become the background where several and different programs aimed at the tourist enhancement have taken place, both in Argentina and in Italy.

Most of them have applied (whether according to clear purposes or not) CBT, collaborative nexogenous approach and social innovation, whose principles are shareable within the collective impact framework.

Based on the methodology of multiple case studies, the cases analyzed in this manuscript allowed the researchers to gradually move from particularity to a certain level of generalization and to get to a broader comprehension of the phenomenon. The comparison—both among different countries and among different programs within the same country—showed clear differences but also a substantial homogeneity of the processes and of the related issues. The small dimensions of the villages, their peripherality, a declining population, fragile socio-economic structures constitute clear elements of similar complexity within the rural villages, often limiting the economic potential of the demand. Some theoretical aspects have been confirmed by the cases, such as the actual presence of adaptive problems (i.e., the tourist transition of the local economies) which need to be addressed through co-evolutive processes involving stakeholders from different sectors within a common agenda and a structured management of the transition, as stated by the collective impact approach.

A novelty of the research paper is to take into the same consideration both the level of integration among the different assets of the countryside capital and the commitments among local actors (eventually combined within the process of CBT), next to the role of the structured coordination played by the extra-local organizations aimed at fostering sustainable tourism development in rural villages. The effectiveness of this local community coordination and the role of the potential backbone support played by the extra-local organizations are also considered as influencing one another.

At the same time, some critical findings emerge from the qualitative analysis of the cases. Even if purposed associations do exist (e.g., SlowFood Presidia, agricultural districts and PDOs consortia, tourist associations), local actors often do not participate in organizing activities within their framework, thus reducing their potential in terms of aims integration and agreement on a common agenda. Also, public-private partnerships are still somehow underused, despite their importance in the rural development programs objectives. The involvement of local authorities and actors in the activities promoted by extra-local organizations is often only formal and does not lead to real opportunities for innovation and local development. National corporations and programs, therefore, still play a weak role and sometimes find it difficult to turn into real backbone organizations.

A clear limitation of the research is the limited number and the geographical localization of the analyzed case studies, which does not allow to infer global tendencies in rural villages tourism development paths. Nevertheless, the paper tries to integrate the knowledge about collaborative ongoing processes with a system of measurement and assessment, which may have a general validity. A further step of the research could be the test of the model on other cases and in different rural contexts of other countries.

The proposed model of measurement is intended to share knowledge and self-assessment among the local community actors about the ongoing processes and, at the same time, as an instrument to plan improvement strategies which can be more focused on the revealed weaknesses. Policy implications on rural tourism development programs management and planning could also be drawn by public authorities and extra-local organizations based on the specific elements highlighted by the research.

Against this background, the paper represents an attempt to move a step further towards a wider meaning of collective impact able to assess not only the results and the impact of single initiatives but the processes in their making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and R.S.; Data curation, E.C., H.L.A., F.P.N. and R.S.; Formal analysis, E.C. and R.S.; Investigation, E.C., H.L.A., F.P.N. and R.S.; Writing—original draft, E.C., H.L.A., F.P.N. and R.S.; Writing—review and editing, R.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kania, J.; Kramer, M. Collective Impact. 2011. Available online: https://communityengagement.uncg.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Collective-Impact.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2018).

- Müller, D.K.; Jansson, B. The Difficult Business of Making Pleasure Peripheries Prosperous: Perspective on Space, Place and Environment. In Tourism in Peripheries. Perspectives from the Far North and South; Müller, D.K., Jansson, B., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore, R.; Chiodo, E.; Fantini, A. Tourism transition in peripheral rural areas: Theories, issues and strategies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedenhann, J.; Wickens, E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—Vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Wornell, R.; Youell, R. Re-conceptualising rural resources as countryside capital: The case of rural tourism. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPan, C.; Barbieri, C. The role of agritourism in heritage preservation. Curr. Issues Tourism 2014, 17, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. (Eds.) Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance; Materiali Uval: Roma, Italy, 2014; Volume 31, pp. 7–64.

- Bertolini, P.; Pagliacci, F. Quality of Life and Territorial Imbalances. A Focus on Italian Inner and Rural Areas. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2017, 6, 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Rofman, A. Nueva Configuración del Espacio en la etapa de la Concentración Capitalista. Voces en el Fenix 2013, 27, 100–107. Available online: http://www.vocesenelfenix.com/sites/default/files/pdf/011.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Dieckow, L.M.; Brondani, N.A.; Cáceres, A.N. Los Impactos Económicos de las Políticas Turísticas: Desarrollo Local o Enclaves Turísticos El Caso Paradigmático De Santa Ana, Misiones, Argentina. Palermo Bus. Rev. Spec. Issue 2012, 6, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Collaboration and Partnerships in Tourism Planning. In Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Bramwell, B., Lane, B., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Polman, N.; Poppe, K.J.; van der Schans, J.W.; van der Ploeg, J.D. Nested markets with common pool resources in multifunctional agriculture. Rivista di Economia Agraria 2010, 65, 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- McComb, E.J.; Boyd, S.; Boluk, K. Stakeholder collaboration: A means to the success of rural tourism destinations? A critical evaluation of the existence of stakeholder collaboration within the Mournes, Northern Ireland. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 17, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, R.; Maretti, M. The Link Between Sustainable Tourism and Local Social Development. A Sociological Reassessment. Sociologica 2012, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chaperon, S.; Bramwell, B. Dependency and agency in peripheral tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanagustin-Fons, V.; Lafita-Cortés, T.; Moseñe, J. Social Perception of Rural Tourism Impact. Sustainability 2018, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. Transition Management as a Model for Managing Processes of Co-evolution Towards Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 2007, 14, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, E. A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H.; Santilli, R. Community-based Tourism: A Success? ICRT Occasional Pap. 2009, 11, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo, E.; Finocchio, R.; Sotte, F. Diversificazione multifunzionale nell’impresa agricola e trasformazioni del paesaggio agrario. Ital. J. Agron. 2009, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Social innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, D.; Sharpley, R. More than sense of place? Exploring the emotional dimension of rural tourism experiences. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. Networks—A new paradigm of rural development? J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural Marginalisation and the Role of Social Innovation; A Turn Towards Nexogenous Development and Rural Reconnection. Sociol. Ruralis 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.B. A Case in Case Study Methodology. Field Methods 2001, 13, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marradi, A.; Archenti, N.; Piovani, J.I. Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales; Emecé: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F.; Hall, D. (Eds.) Tourism in Peripheral Areas. Case Studies; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mahony, K.; van Zyl, J. The impacts of tourism investment on rural communities: Three case studies in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2002, 19, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINTUR—Ministerio de Turismo de la Nación. Anuario Estadístico 2014; MINTUR: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015.

- Manzanal, M. Desarrollo Territorial e Integración Nacional ¿Convergencia o Divergencia? In Territorios, Identidades y Federalismo; Nun, J., Grimson, A., Eds.; Edhasa: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Reboratti, C. El noroeste entre la globalización y la marginación. Geograficando 2014, 10, 2. Available online: https://www.geograficando.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/Geov10n02a06 (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Schweitzer, A.F. Patagonia, naturaleza y territorios. Geograficando 2014, 10, 2. Available online: https://www.geograficando.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/Geov10n02a11 (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Valenzuela, C. Implicancias del avance de la “frontera” agropecuaria en el Nordeste Argentino en las últimas dos décadas. Estudios Socioterritoriales Revista de Geografía 2014, 16, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Reboratti, C. Un mar de soja: La nueva agricultura en Argentina y sus consecuencias. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande 2010, 45, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanal, M.; Arzeno, M.; Bonzi, L.; Ponce, M.; Villarreal, F. Poder y conflicto en territorios del norte argentino. Estudios Socioterritoriales Revista de Geografía 2011, 9, 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Guastavino, M.; Rozemblum, C.; Trímboli, G. El turismo rural en el INTA. In Proceedings of the Primer Encuentro de Economía Agraria y Extensión Rural, San Luis, Argentina, 6–8 October 2010; Available online: http://www.aader.org.ar/XV_Jornada/trabajos/espanol/Estrategias_y_experiencias/ensayos/Trabajo%2075%20Completo.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2018).

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncello, R.; Iuso, R. Turismo urbano en contexto metropolitano: Tigre como destino turístico en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires (Argentina). Cuadernos de Geografía: Revista Colombiana de Geografía 2016, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO—United Nations World Tourism Organisation. Panorama OMT del Turismo Internacional; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Desarrollo y Promoción Turística. Encuesta de Viajes y Turismo de los Hogares. In Turismo interno: Segundo Trimestre de; Secretaría de Desarrollo y Promoción Turística: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, F.; Schluter, R. El turismo en los pueblos rurales de la Argentina ¿Es la gastronomía una opción para el desarrollo? Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo 2010, 19, 909–929. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, G. Ruralità e turismo. Agriregionieuropa 2010, 20, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, E.A.L. Relación ciudad-campo y turismo rural. Ensayos teórico-metodológicos. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo 2012, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, A.; Rover, O.J.; Chiodo, E.; Assing, L. Agroturismo e orientação aos circuitos curtos de comercialização de alimentos orgânicos: Estudo do caso “Acolhida na Colônia”. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural RESR SOBER 2018, 56, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.; Thiel Ellul, D. Desarrollo, impacto y sostenibilidad del turismo gastronómico en el ámbito local. El caso de Tomás Jofré, provincia de Buenos Aires. In Proceedings of the Actas 5to Congresso Latino-Amerciano de Investigacao Turística, São Paulo, Brasil, 3–5 September 2012; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wyss, F. Informe Introductorio de Base: Análisis del Turismo Rural en las Américas. In Proceedings of the OMT. El Turismo Rural en las Américas y su Contribución a la Creación de Empleo y a la Conservación del Patrimonio, Asunción, Paraguay, 12–13 May 2003; pp. 17–66. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, S.; Hunter, C.; Blackstock, K. A typology for defining agritourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, C.G.; Barbieri, C.; Rich, S.R. Defining agritourism: A comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Lumsdon, L.; Robbins, D. Slow Travel: Issues for Tourism and Climate Change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballo-Lascurain, H. (Ed.) Tourism, Ecotourism and Protected Areas; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ONT—Osservatorio Nazionale del Turismo. Il turismo enogastronomico. 2018. Available online: http://www.ontit.it/opencms/opencms/ont/it/documenti/index.html?category=documenti/ricerche_ONT (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Ohe, Y.; Ciani, A. Evaluation of agritourism activity in Italy: Facility based or local culture based? Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Ciani, A. Accessing Demand Characteristics of Agritourism in Italy. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 18, 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Anno 2017. Le Aziende Agrituristiche in Italia. 2018. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/221471 (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Flores, F.; Rebottaro, A. El “otro” Luján turístico. El caso de Carlos Keen. Revista del Departamento de Ciencias Sociales 2016, 3, 214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciutto, M.; Roldán, N.G.; Corbo, Y.A.; Cruz, G.; Barbini, B. Análisis de la participación social en el marco del programa “Pueblos Turísticos”. El caso de Carlos Keen. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2015, 13, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabini, V.D. El Turismo Comunitario en pequeñas localidades rurales: Análisis de los impactos económicos en Carlos Keen a partir de la implementación del Programa “Pueblos Turísticos”. Departamento de Turismo, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. 2016. Available online: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/61223 (accessed on 10 June 2018).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).