Does Employees’ Participation in Decision Making Increase the level of Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability? An Investigation in South Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Corporate Sustainability

2.1. Environmental Sustainability Practices (ESPs)

2.2. Societal Sustainability Practices (SSPs)

2.3. HR Sustainability Practices (HRSPs)

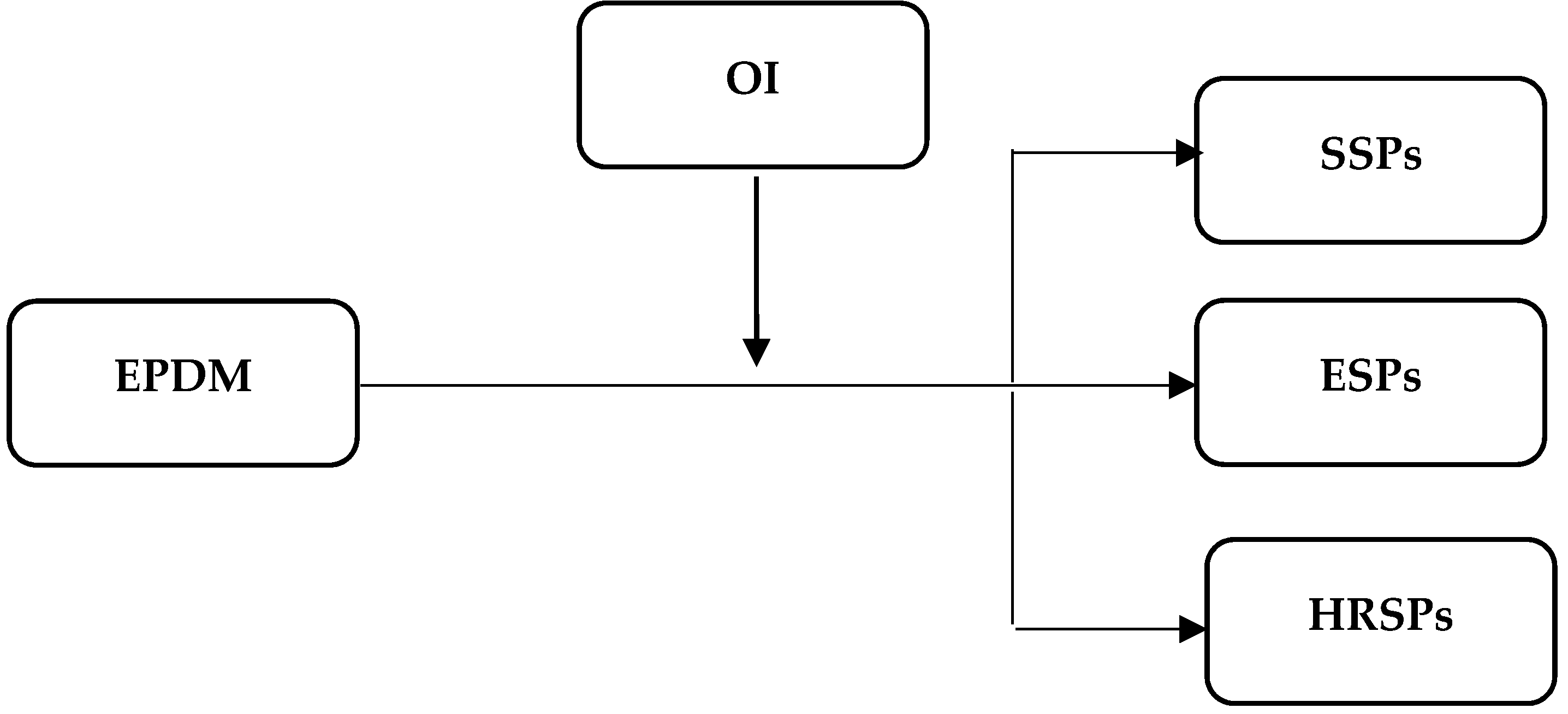

3. Hypotheses

4. Methods

4.1. Sample and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Measurement Validity and Reliability

4.4. Common Method Variance

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

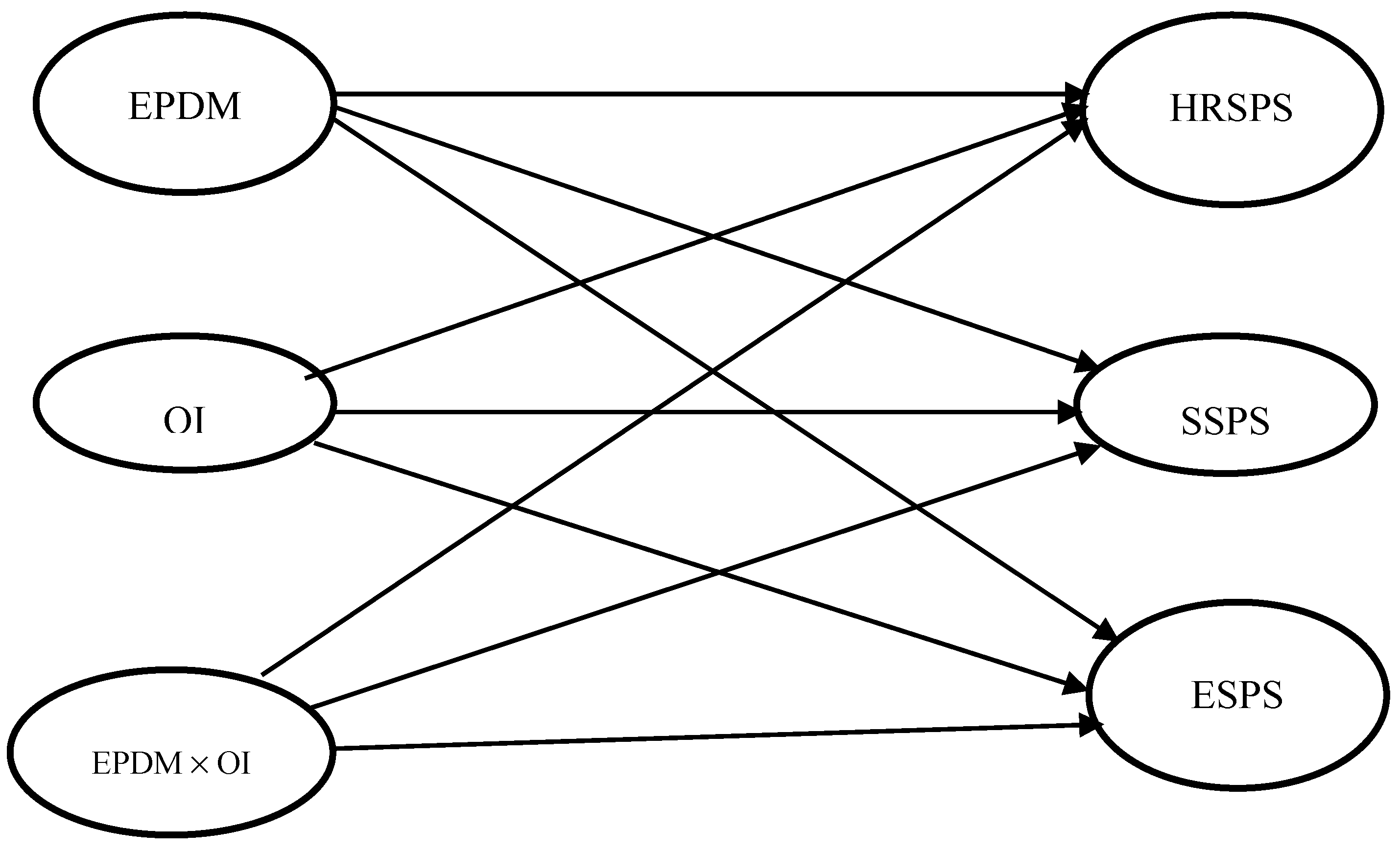

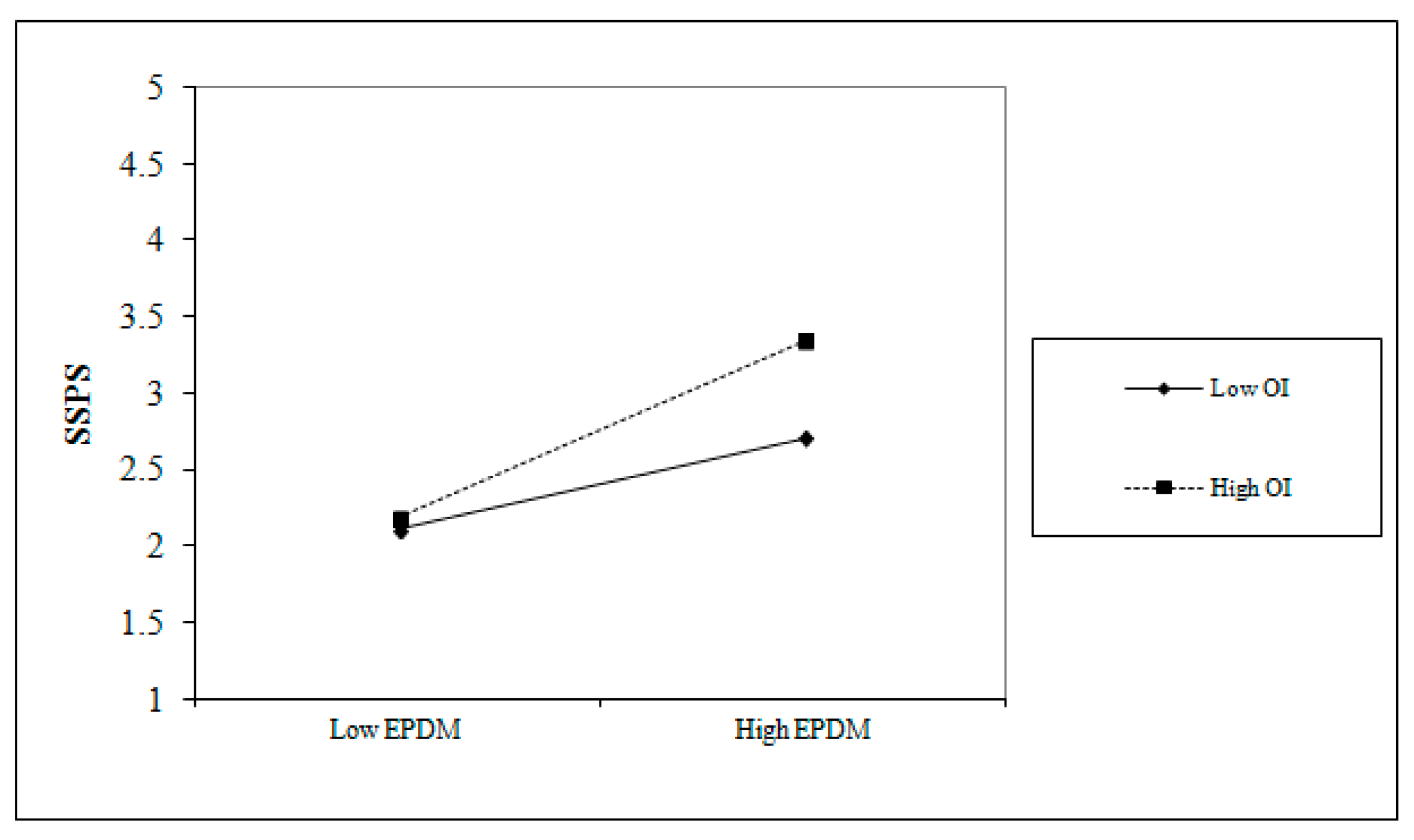

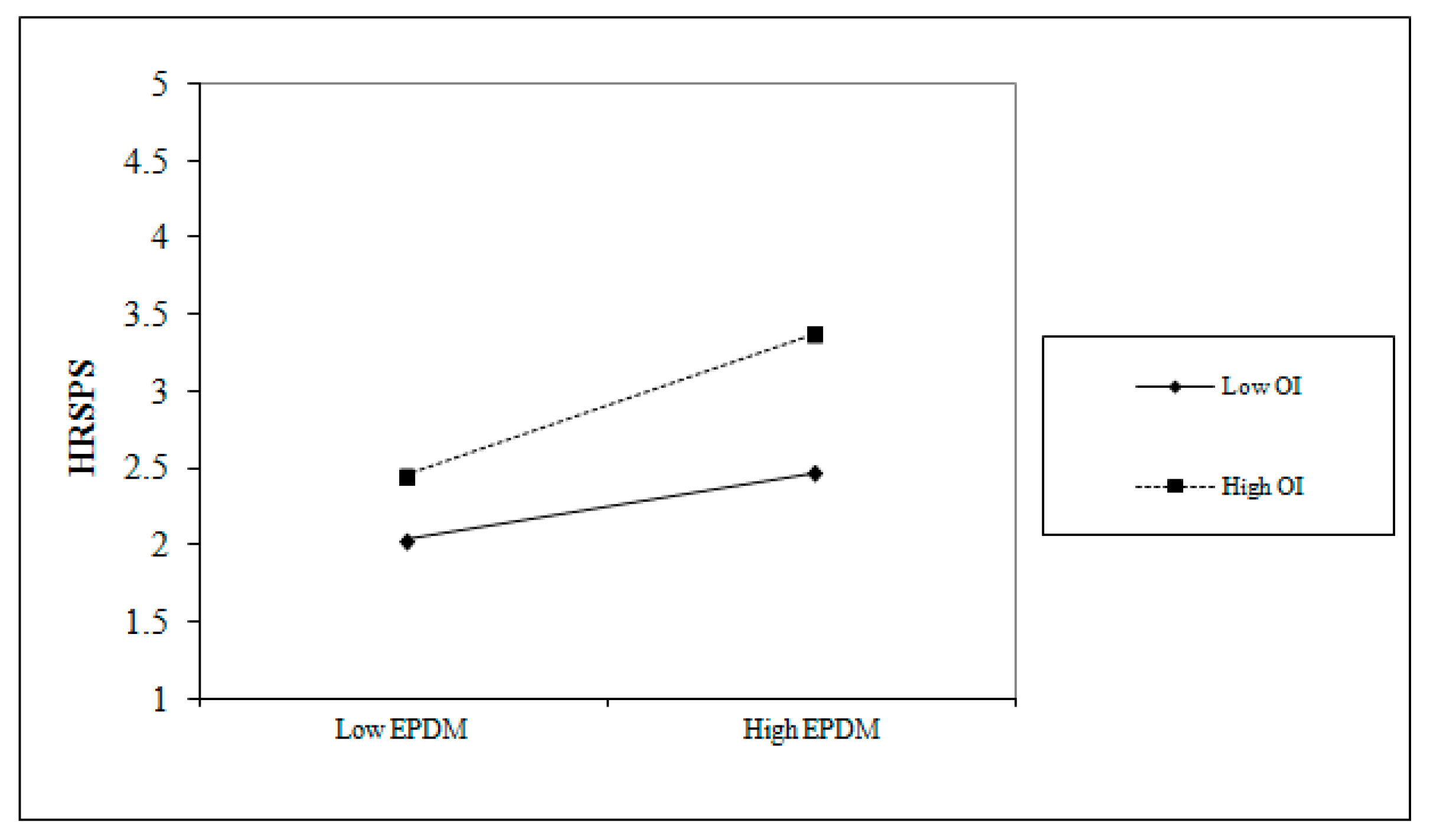

5.2. Hypotheses Testing

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1997; Available online: http://appli6.hec.fr/amo/Public/Files/Docs/148_en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B.; Caggiano, J. Creating sustainable value [and Executive Commentary]. Acad. Manag. Exec. (1993–2005) 2003, 17, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.J.; Hope, C. Incorporating sustainable business practices into company strategy. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2007, 16, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Environmental technologies and competitive advantage. Strat. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Hart, S. Creating sustainable corporations. Bus. Strat. Environ. 1995, 4, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, J.W.; Ramstad, P.M. Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.E.; Huselid, M.A. High performance work systems and firm performance: A synthesis of research and managerial implications. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 16, 53–101. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.P. High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from New Zealand. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, C.A.; Steger, U. The roles of supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee “Ecoinitiatives” at leading-edge European companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.T.; Kim, N.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Farooq, O.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Employees response to corporate social responsibility: Exploring the role of employees’ collectivist orientation. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Farooq, O. Corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership: Investigating their interactive effect on employees’ socially responsible behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Rupp, D.E. Social responsibility in and of organizations: The psychology of corporate social responsibility among organizational members. In Handbook of Industrial, Work, and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Andersons, N., Ones, D.S., Sinangil, H.K., Viswesvaran, C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, N.; Fern, C.T.; Budhwar, P. Explaining employee turnover in an Asian context. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2001, 11, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity theory. In Contemporary Social Psychological Theories; Burke, P.J., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability: An investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. Insights into triple bottom line integration from a learning organization perspective. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2006, 12, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Reconciling sustainability and growth: Criteria, indicators, policies. Sustain. Dev. 2004, 12, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Leal, S.; Cunha, M.; Faria, J.; Pinho, C. How the perceptions of five dimensions of corporate citizenship and their inter-inconsistencies predict affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A. Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberson, C.L.; Healy, M.; Romero, V. Ingroup bias and self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 4, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of group behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J. Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. Why people cooperate with organizations: An identity-based perspective. Res. Organ. Behav. 1999, 21, 201–246. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, T.I.; Moldoveanu, M. When will stakeholder groups act? An interest-and identity-based model of stakeholder group mobilization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A. Group norms and the attitude-behavior Relationship: A role for group identification. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 22, 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.J.; Millington, A.I. Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Jia, W. The fortune corporate ‘reputation index’: Reputation for what? J. Manag. 1994, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.J. The Effects of Employee Ownership on Job Attitudes and Organizational Performance: An Exploratory Study. doctoral dissertation. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Yun, S.U.N.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar]

- Delery, J.E.; Doty, D.H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 802–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Analysis of the Human Relations Policies and Practices in England, Norway, Holland, France, Greece and Germany; OECD Department of Management Reports: Paris, France, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Long, R.J. The effects of employee ownership on organizational identification, employee job attitudes, and organizational performance: A tentative framework and empirical findings. Hum. Relat. 1978, 31, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, A.S. Social Psychology of the Work Organization; Tavistock: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. Employees’ response to corporate social responsibility: An application of a non linear mixture REBUS approach. In New Perspectives in Partial Least Squares and Related Methods; Abdi, H., Chin, W.W., Vinzi, V.E., Russolillo, G., Trinchera, L.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Monroe, G.S. Exploring social desirability bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. To be or Not to Be? Central questions in organizational identification. In Central Questions in Organizational Identification; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D.K. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E. An Empirical Inquiry into the Social Responsibilities as Defined by Corporations: An Examination of Various Models and Relationships. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Loyal from day one: Biodata, organizational identification, and turnover among newcomers. Person. Psychol. 1995, 48, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. Methodology. 1980, 2, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, (Methodology in the Social Sciences); Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, J. Common Method Bias Using Common Latent Factor. Available online: https://youtu.be/Y7Le5Vb7_jg (accessed on 14 February 2018).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Csection Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, W.P. Participative Management, Reading, Mass; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, C.F.; Wakeley, J.H.; Ruh, R.A. The Scanlon Plan for Organization Development: Identity, Participation, and Equity; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Melcher, A.J. Participation: A critical review of research findings. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1976, 15, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J.L.; Vollrath, D.A.; Froggatt, K.L.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L.; Jennings, K.R. Employee participation: Diverse forms and different outcomes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M. Changing employee attitudes. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2002, 38, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The Social Psychology of Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kuvaas, B. Performance appraisal satisfaction and employee outcomes: Mediating and moderating roles of work motivation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Alpha Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSPs | 0.61 | 0.91 | ||||

| SSPs | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.85 | |||

| ESPs | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.91 | ||

| EPDM | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.66 | 0.89 | |

| OI | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.60 | 0.88 |

| Variables | Mean | St. Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSPs | 4.1 | 1.26 | 1 | ||||

| SSPs | 3.65 | 1.33 | 0.59 * | 1 | |||

| ESPs | 3.39 | 1.41 | 0.44 * | 0.58 * | 1 | ||

| EPDM | 4.81 | 1.07 | 0.47 * | 0.56 * | 0.30 * | 1 | |

| OI | 4.44 | 1.21 | 0.43 * | 0.42 * | 0.35 * | 0.49 * | 1 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | HRSPs | SSPs | ESPs |

| EPDM | 0.34 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.21 *** |

| OI | 0.33 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.29 *** |

| EPDM × OI (interaction term) | 0.12 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.04 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farooq, O.; Farooq, M.; Reynaud, E. Does Employees’ Participation in Decision Making Increase the level of Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability? An Investigation in South Asia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020511

Farooq O, Farooq M, Reynaud E. Does Employees’ Participation in Decision Making Increase the level of Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability? An Investigation in South Asia. Sustainability. 2019; 11(2):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020511

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarooq, Omer, Mariam Farooq, and Emmanuelle Reynaud. 2019. "Does Employees’ Participation in Decision Making Increase the level of Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability? An Investigation in South Asia" Sustainability 11, no. 2: 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020511

APA StyleFarooq, O., Farooq, M., & Reynaud, E. (2019). Does Employees’ Participation in Decision Making Increase the level of Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability? An Investigation in South Asia. Sustainability, 11(2), 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020511