Abstract

This paper proposes a conceptual model using four failed mergers (Federated -Fingerhut, KCPL and Western Resources, Daimler–Chrysler and Alcatel–Lucent) and distinguishes two types of dimensions: type of failure (tangible and intangible) and degree of failure (fixable and unfixable). Using case studies as a research strategy and focusing on the Alcatel–Lucent merger, as an example of an idiosyncratic type of “merger of equals”, the model identifies the entrepreneurial conflict variable as a missed step for obtaining a sustainable merger process over time.

1. Introduction

The business history over the last 30 years shows how merger activity is one of the chief methods for growing. For that reason, experts and executives are still searching for models and indicators that provide guarantees of success. The literature regarding mergers is huge, and it is even greater in the case of looking for success [,,,,,,].

For example, classical studies on industrial mergers have differentiated merger success and merger failure by analyzing its behavior during its first decade and statistically ascertaining success in terms of earnings on capitalization [,]. On the other hand, present studies study merger success in a complex analysis of formal financial elements (accounting, budgeting) and nonfinancial elements (strategy, leadership and culture) [].

Failure has been couched in terms as “resale” or “liquidation”, or as “failing to reach certain projected growth or profit” []. Failure also occurs when mergers are announced because the firm’s stock-acquiring process tends to fall slightly and when the profitability of the acquired firm is lower after being sold off (relative comparable non-merged firms) [].

This article examines mergers’ behavior from the failure viewpoint, following the contributions of authors as Ravenscraft and Scherer [,] who have shown the most conclusive evidence of lower post-merger sustainability—measured by financial tangible elements of profitability or labor productivity. By other way, authors such as Weber and Camerer [], have identified intangible elements such as cultural conflict and entrepreneurial behavior, both of which are responsible for reaching an unsustainable merger development process.

The sustainability concept has been applied to several fields: environmental, economic and social []. This article analyzes an economic concept of sustainable merger considering missteps involved in the process as for example intangible elements which are not being considered within a classical pre-merger planning.

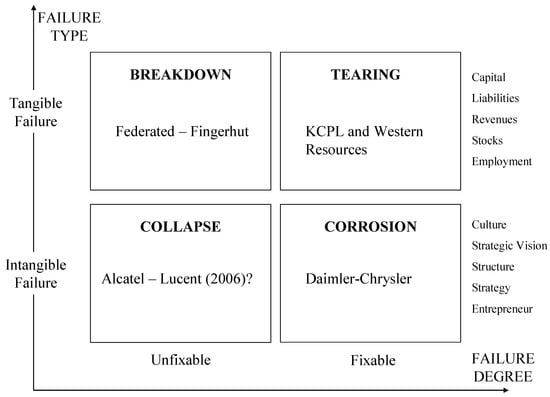

This article proceeds as follows: The first section is dedicated to a literature review which analyses the complexity of obtaining successful mergers; the following section explains the conceptual model of the paper based on the failure viewpoint and its importance for practitioners, as well as the justifying material and methods used in the model; the third section explains the proposed theoretical model built using four failed mergers (Federated–Fingerhut, KCPL and Western Resources, Daimler–Chrysler and Alcatel–Lucent), in the process distinguishing two variables:

(1) Type of failure: On one hand, the tangible ones which come from quantitative elements such as capital, liabilities, revenues or stocks, and onthe other hand, the intangible ones such as culture, strategic vision or entrepreneurial relationship; and

(2) degree of failure, which could be fixable or unfixable during the merger process.

From the combination of both variables, we propose a model of four stages of failure for a merger: breakdown, tearing, corrosion and collapse. This last one is developed in depth in the discussion using the specific case of the Alcatel and Lucent merger, identifying the entrepreneurial conflict as responsible for the failure. Finally, we provide the conclusions and future lines to research.

2. Literature Review

Success and failure in mergers are one of the most studied topics by academics and practitioners [,,], and over the last 30 years, merger activity has been considered one of the chief strategies for organization of growth [].

The decision about what merger type is more suitable in a specific case depends on the motive for which two firms want to merge. For example, a classical example of a horizontal merger is between British Airways and British Caledonian in 1987. In this case, the motives for merger were: On the one hand, the creation of scale and scope economies, which allowed British Airways to gain access to the airport rights held by British Caledonian and to reduce the competition on those routes; and, on the other hand, a further increase in size of the firm due to market power.

The market power motive, usually associated with a horizontal merger, can be enhanced if there are no available substitutes for the monopolized input through vertical integration [,]. The use of a vertical merger to monopolize the market is illegal in most countries because this type of merger establishes entry barriers through the control of supply or through cost advantages that a vertical organization possesses. An example of backward vertical integration has been noted in the United Kingdom with the privatization of the electricity-generating industry, where there has been greater scope to generate some of their own electricity needs.

There are three major types of mergers: horizontal, vertical and conglomerate. A conglomerate or diversification merger introduces organizational behavior to new markets and new products not related to current business activities. In the United Kingdom during the 1960s, between 10 and 15 per cent of the growth of firms was through conglomerate mergers, and by the 1980s, this merger form represented around 30 per cent of all merger activity [].

An example of this behavior could be observed in the Hanson Trust, but it differs in this conglomerate concept because it bought up cheap firms not in order to attain long-term strategic goals. The Hanson Trust came about in the 1960s at the hands of Lord Hanson, a successful British businessman []. The behavior pattern was to generate a firm‘s cash to repay the debt incurred to fund the acquisition and to deliver dividends to shareholders. The Hanson techniques have become standard business practice (from rewarding managers for maximizing shareholder value to focusing on cash generation). So, trying to answer the question about entrepreneurship conflict in mergers, size issue is outlined as a key element [].

In the case of growth through acquisitions, a smaller firm is fitted into the existing structure of a larger organization. In conglomerate cases, large companies are brought together without the advantages of decentralization and autonomy being lost. However, “mergers of equals”, which involves two firms of comparable stature coming together and acquiring the best of each partner to create a completely new organization; two leaders will manage the merged firm together, will take decisions together and will represent the survival of the culture and the soul of each merged firm, and afterwards they will fight for getting the business control.

3. Case Studies to Develop a Conceptual Model of Failure Merger

Using case studies as a research strategy, which has been used too by classic scholars as well as relevant authors of management literature [,,], we propose a conceptual model to focus the entrepreneurial conflict as a missed step in a sustainable merger process over time.

Authors such as Eisenhardt and Graebner [] hold that theory building from case studies is one of the best bridges from rich qualitative evidence to deductive research. Even more, they published an article in one of the lead journals of management, which has been cited more than 11,630 times. In that paper, they justify the meaning of theoretical sampling as selected cases particularly suitable for illuminating and extending relationships and logic among constructs. So, following this research method we have selected concrete merger cases based on their uniqueness which help to understand the idiosyncratic detail of each one.

In this way, this paper proposes a theoretical model using four failed mergers (Federated–Fingerhut, KCPL and Western Resources, Daimler–Chrysler and Alcatel–Lucent) and distinguishes two types of dimensions: type of failure (tangible and intangible) and degree of failure (fixable and unfixable) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Failure analysis (own work).

Tangible failure defines two aspects of the deal structure: price premium and financing type. Hartman [] quotes numerous studies which conclude that between 60 and 80 percent of all mergers are unsuccessful, overestimation of benefits and underestimation of the difficulties entailed in the integration of merged firms being the relevant reasons. According Epstein [], “mergers often fail due to paying too high a purchase price and overburdening the new company with sky-high debt payments”. So, both partners must consider whether their stocks are overvalued or undervalued at the time of the deal. Summarizing, tangible failures are caused by financial elements.

An example of tangible failure in mergers is the merger case of Federated and Fingerhut. Federated paid about 30 per cent premium price in the deal and sold the operation for less than US$ 800 million in 2002, after purchasing the firm for US$ 1.7 billion in 1999 []. This unsuccessful and unsustainable merger case is unfixable and originated by tangible failure. In our failure analysis, this combination of tangible and unfixable failure merger is called “Breakdown”.

Kansan City Power & Light (KCPL) and Western Resources (now known as Westar Energy) is an example of a tangible and fixable failure of merger. This merger terminated in January 2000 due to financial problems of Protection One (a Western Resources subsidiary) and the related decline in Western Resources’ stock price. KCPL expected to grow as a result of the merger from unregulated businesses including subsidiaries (as Protection One), so this expectation suggests that better financial information regarding subsidiaries could have kept the merger agreement. Following the proposed failure analysis, this tangible and fixable failure in a merger is called “Tearing” (see Figure 1).

The failures defined as intangible should be nonfinancial elements such as the ability to merge cultures, building a joint strategic vision, the evaluation of structure fit, understanding the strategy being used; the entrepreneurs are considered in this paper.

The merger of Daimler and Chrysler was defined by several experts and practitioners as a “merger of equals”, which means that each unit benefits from the other’s strengths and capabilities. The previous financial analysis of both companies reflected optimism about the merger. However, differences in culture between both firms caused the merger failure []. The merger was not developed between “equals” because Daimler–Benz and Chrysler had different ways of operating. Daimler’s culture was more stressful, formal and structured whereas Chrysler’s culture allowed a freewheeling style.

The conflict centered on different views on pay scales and travel expenses. The original aim was to share research and processes but differences in corporate policies caused difficulties in the merger. This intangible failure is due to the integration process not being adequately managed. So, this intangible failure could have been resolved. Following the proposed failure analysis, this intangible and fixable failure in this merger is called “Corrosion” (see Figure 1).

Finally, intangible and unfixable failure (“Collapse”) is presented through the case of Alcatel and Lucent. Their entrepreneurs are analyzed as potential failures in this merger. In order to develop this business case from the entrepreneurial viewpoint, first it is necessary to outline a conceptual dimension of the entrepreneur variable (see Figure 1).

The entrepreneur is the one who creates new industries and new markets and promotes major changes in the economy [,,]. So, most markets are created because an entrepreneur has decided to set them up [].

Firms act as market-making intermediators and the entrepreneur is the coordinator of information that he obtains first-hand, by direct observation or second-hand through communication with other people. A merger is a type of tool by means of which the entrepreneur acquires information, and in this way, he turns the information into research and development. However, the information is subjective, and in view of the possibility that two entrepreneurs might have the same information, its interpretation would be different because the nature of its interpretation depends on the identity of the person making it. Thus, the key role of the entrepreneur is based upon a synthesis of information that he must coordinate.

In a merger case, two coordinators must make decisions together, but a coordinator cannot implement a plan without control over resources. Following Markham [], some mergers are the “means by which some entrepreneurs make their exit from the industry, selling their undepreciated assets to other entrepreneurs”. After a merger, it is very important that the new firm defines its new resources and its new property rights, because if not, every entrepreneur would be able to promote rival plans against the other one. So, if the information is often highly subjective and every judgement of a situation is potentially unique for every entrepreneur, the new merged firm could be managed by two heads which provide two different perceptions of any given situation. For this reason, the analysis of entrepreneurial decisions because of personality characteristics has become a relevant issue for researchers and practitioners [].

A Meyer–Briggs type indicator (MBTI) regarding entrepreneur personality preferences is one of the most used by researchers. This indicator is based on Jungian Theory and it establishes four entrepreneurial behaviors: (1) Extroversion–Introversion: modes of orientation to the world; (2) Sensing–Intuitive: ways of Perceiving; (3) Thinking–Feeling: how judgments are formed; and (4) Judging–Perceptive: about the decision-making process. For example, Westerman et al. [] used the MBTI to determine the interaction of personality type with academic performance for persons in their first year of dental school. They only found low and non-significant correlations between MBTI type and success as measured by grade point averages.

Murray and Johnson [] used this instrument to identify the types of females who were more successful at the US Naval Academy, and Shuit [] used MBTI to demonstrate how individuals of different types approach their work and problem solving in a different manner.

However, entrepreneurial behavior should be particularly analyzed and not classified according to subjective characteristics such as ways of thinking or perceiving. An entrepreneur’s objective characteristics would be experience in management positions, previous knowledge in mergers or any other relevant and personal data.

Thus, a 5W tool is proposed as a way of knowing the objective characteristics of every partner before merging: Who is the entrepreneur? (Relative in family business?); when did the entrepreneur arrive in the firm? (Degree of knowledge about his firm); what is his experience in the merger? (is it the first one?); why has he decided to merge? (Personal interests or firm’s interests), and finally, where does the success of his firm lie? (Competitive advantages). The 5W tool tries to study what the entrepreneurs’ behavior for every partner firm could be.

In this context, Lewin’s studies [] propose a person’s behavior function based on two variables: A person who takes decisions and his environment []. It means that one entrepreneur could be a potential failure in a merger depending on the environment where the merger is developed. So, the environment issue is presented as a key point of analysis in the degree of failure in a merger, which could be fixable or unfixable depending on the circumstances.

So, after explaining the personal details of each partner, the second step of Lewin’s analysis is the environment where the merger is going to be developed. The environment variable is defined by three key points: merger motive, merger type and merger size. Let suppose an entrepreneur in the fourth generation of a family business, who was brought into the firm slowly, and, thanks to succession planning, has experience in previous mergers; he decides to merge in order to grow and his firm possesses tangible and intangible competitive advantages.

So, in order to analyze the entrepreneurial failure in a merger of equals context, we present the Alcatel and Lucent Technologies merger as an entrepreneurial failure in a merger of equals context.

4. Discussion about the “Collapse” Case of the Alcatel and Lucent Merger

Alcatel and Lucent Technologies have been defined by several experts and practitioners as “merger of equals”. The proposed merger in 2001 fell apart after Lucent saw itself as being acquired by the larger Alcatel. Lucent is now in better shape than in 2001 and considering that it was spun off from AT&T in 1996 (AT&T Technologies, Inc., the former Western Electric), the company has seen its business legacy decline. For Alcatel, a merger could give it a greater U.S. presence. Alcatel is strong in ADSL and it would also be able to compete with Cisco for VoIP or triple-play business due to Lucent providing it with access to the Baby Bells.

A financial market reporter at USA Today, Matt Krantz [], describes this French–American merger as follows:

“With few exceptions, when companies say they “merged,” what they’re really saying is that one company was acquired. Why don’t they just say that? Maybe it’s an ego thing, but for whatever reason, many acquired companies don’t want to fess up. And the acquiring company helps the target save face. That’s kind of what happened here. The companies went to great lengths to try to hide the fact that Alcatel was buying Lucent. They used terms like "merger of equals" to disguise the fact. Some investors might think—that Lucent is an equal in the deal because Lucent’s CEO Patricia Russo will be CEO of the new company”.

Following Lewin’s behavior function, a merger analysis requires two aspects: a person and an environment. Merger behavior depends on the entrepreneur’s behavior and the merger environment. The Alcatel–Lucent merger behavior is an example of how entrepreneurial failure type could be developed.

Firstly, person behavior is studied through the 5W tool in order to obtain relevant information about merger partners. Lucent’s entrepreneur is Patricia Russo and Serge Tchuruk is Alcatel’s entrepreneur.

The 5W tool presents two solid entrepreneurs, independent of their company, with adequate experience in management and in merger leadership (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Entrepreneur analysis in Alcatel-Lucent Merger (Own work from Alcatel and Lucent’s reports).

Serge Tchuruk is the Non-Executive Chairman and Patricia Russo is the CEO in the new company Lucent–Alcatel. Board composition is international: Six of Alcatel’s current directors (including Tchuruk), six of Lucent’s current directors (including Russo) and two new independent European directors who will be mutually agreed upon. The expected closing date of this merger is between 6–12 months from the merger announcement in April 2006.

Secondly, the Alcatel–Lucent merger environment is analyzed from three aspects: merger motive, merger type and size. A merger of equals, as Alcatel-Lucent calls it, defines the size aspect.

They are two similar-sized companies coming together to create a new organization with significant competitive advantages. In the Alcatel–Lucent case, the fixed exchange ratio is 0.1952; approximately, Alcatel shareowners possess 60 percent while 40 percent is owned by Lucent shareowners.

Although in 2001 Lucent saw itself as being acquired by Alcatel and for that reason that proposed merger was rejected, the fixed exchange ratio demonstrates that Alcatel could be the acquiring firm once again. Whereas an acquisition causes a sense of which company is in charge, a merger of equals often conveys a power struggle as members of both companies are determined to gain control over the new company [].

An Alcatel–Lucent merger report [] specifies the following benefits of scale and scope: ongoing consolidation of global service providers, increasing network complexity and convergence, major network transformation, significant R&D investment in order to maintain leadership, and scale- and scope-enhancing competitiveness. The motives of market power and scale economies are usually associated with horizontal mergers. While Alcatel’s competitive advantage is its strength in ADSL, Lucent’s advantage is accessibility to the Baby Bells. For Alcatel, a merger with Lucent could provide a greater American presence. In this exchange, the Alcatel–Lucent’s CEO would be Patricia Russo (Lucent’s CEO). So, the environment merger analysis of Alcatel–Lucent is: merger of equals + market power and scale and scope economies + horizontal merger.

In the Alcatel–Lucent merger report [], they also explain what their common vision and innovation culture must be in order sto uccessfully meet their goal: shared vision of network transformation; common culture of technical excellence and innovation; deep understanding of customer needs; industry leading depth and breadth of talent; and geographic, portfolio and customer fit. They hold: “two companies and one common vision”. It is particularly interesting when two companies with one common vision have two heads (Russo and Tchuruk), and at least the two independent members of the board must be mutually agreed upon. In addition, this argument is also most interesting when approximately 60 percent of Alcatel’s shareowners are not directly represented by Alcatel’s CEO (Tchuruk).

On analyzing the failure process according to type dimension and degree dimension, the Alcatel–Lucent merger does not present tangible failures a priori (combined revenues of €21/$25 billion and cash of €9/$11 billion). However, intangible failures could appear post-merger. In the Alcatel–Lucent merger report [], intangible variables such as culture, strategic vision, synergy structural costs (approximately €10/$12 billion), and strategic fit (right time, right solutions and right companies) are considered in pre-merger planning, but not in entrepreneur failure.

Tchuruk and Russo are two heads in a new organization whose merger was called “of equals” without that point being completely resolved in the first merger attempt in 2001. Furthermore, two powerful entrepreneurs who are used to managing merger leadership, with experience within their firms and with the same aims, could represent a failure type in merger. So, if they are a potential intangible failure, they should be analyzed during pre-merger planning. The power struggle to seek control over the new organization ends when one of the entrepreneurs wins and the merger turns into a takeover or when the merger is broken due to financial problems caused by wrong management during the entrepreneurial conflict.

Focusing on the second dimension of failure analysis, the degree of failure in a merger could be fixable and unfixable. The potential entrepreneurial failure found in the Alcatel–Lucent merger is more likely to be unfixable (“Collapse”) than fixable (“Corrosion”) due to there being two entrepreneurs (Russo and Tchuruk) and due also to the previous response of Lucent in 2001 when it saw itself as being acquired by Alcatel. The Alcatel–Lucent merger case shows the existence of another intangible failure in mergers, which should be studied in pre-merger planning: the entrepreneur variable.

October 1st, 2008: Alcatel–Lucent announced changes to its leadership and Board of Directors. Non-Executive Chairman Serge Tchuruk and Patricia Russo decided to step down. Russo decided to step down at the end of that year until a new CEO was in place and to maintain the continuity of the company´s business. The same announcement holds “The Board will commence a search for a new non-executive Chairman and CEO immediately”. Tchuruk said that “It is now time that the company acquires personality of its own, independent from its predecessors”; and Russo added: “The company will benefit from new leadership aligned with a newly composed Board to bring a fresh and independent perspective that will take Alcatel-Lucent to its next level of growth and development in a rapidly changing global market. I have every desire to ensure a smooth transition of leadership within the company”.

This leadership conflict between two heads from different business cultures, ways of doing things and aims has been resolved 2 years after the merger with a new Board of Directors and even with a new personality which must be built for the new CEO following the Alcatel–Lucent announcement of 2008. So, a new business is built after Russo and Tchuruk and the merger phase with the conflict leadership is defined by them as “transitional”. At this point, we could ask ourselves if leadership conflict in a “merger as equals” is a transitional phase of a merger or a missing motive in the pre-merger planning.

Alcatel and Lucent’s merger is an interesting example where collapse is not defined yet but the changes to its management team and Board of Directors indicated in the beginning an unsustainable merger where intangible elements such as leadership conflict were missed by the planning process.

5. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

This paper proposes a framework for studying merger failure where intangible elements should be considered as well as tangible elements. In this way, four results of mergers are explained by four behaviors: Breakdown, Tearing, Corrosion, and Collapse.

The Alcatel and Lucent merger is an interesting example defined as a collapse. The changes to its management team and Board of Directors indicated in the beginning an unsustainable merger where intangible elements such as entrepreneurship conflict were missed by the pre-merger planning.

In this way, “mergers of equals” established a new framework for future lines of research, which could be very useful for academics, executives, consultants, and even CEOs affected by a merger process. Tools such as Lewin’s behavior function and 5W are not unique in obtaining relevant information about merger partners. Other indicators which could be able to provide relevant details of each partner and their environment will be very useful in preventing unsustainable mergers built on failure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and F.C.; Methodology, M.S. and F.C.; Software, X.X.; Validation, M.S., F.C. and R.C.; Formal Analysis, M.S. and F.C.; Investigation, M.S. and F.C.; Resources, M.S., F.C. and R.C.; Data Curation, M.S. and F.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dewing, A.S. A Statistical Test of the Success of Consolidations. Q. J. Econ. 1921, 36, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J. The Determinants and Evaluation of Merger Success. Bus. Horiz. 2005, 48, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroski, P.A.; Vlassopoulos, A. Recent Patterns of European Merger Activity. Bus. Strategy Rev. 1990, 1, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.B.; Cromley, R.G. The Horizontal Merger: Its Motives and Spatial Employment Impacts. Econ. Geogr. 1982, 58, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R. The Efficiency Effects of Utility Mergers: Lessons from Statistical Cost Analysis. Energy Low J. 1996, 425, 437–439. [Google Scholar]

- Livermore, S. The Success of Industrial Merger. Q. J. Econ. 1935, 50, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B.R. What Do We Conclude from the Success and Failure of Mergers? J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2001, 1, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.F. Corner boys: A study in clique behavior. Am. J. Soc. 1941, 46, 647–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscraft, D.J.; Scherer, F.M. Life After Takeover. J. Ind. Econ. 1987, 36, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscraft, D.J.; Scherer, F.M. The Profitability of Mergers. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 1989, 7, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.A.; Camerer, C.F. Cultural Conflict and Merger Failure: An Experimental Approach. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; Kishawy, H.A. Sustainable Manufacturing and Design: Concepts, Practices and Needs. Sustainability 2012, 4, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.P.; Santos, J.C.; de Almeida, M.I.R.; Reis, N.R. Mergers & acquisitions research: A bibliometric study of top strategy and international business journals, 1980–2010. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. The impact of firms’ mergers and acquisitions on their performance in emerging economies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2018, 135, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.; Farquharson, C. Business Economics; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Junni, P.; Sarala, R.M. The role of leadership in mergers and acquisitions: A review of recent empirical studies. In Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 181–200. ISBN 9781783509706. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, R.J.; Simkowitz, M.A. Investment Characteristics of Conglomerate Targets: A Discriminant Analysis. South. J. Bus. 1971, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, A.D. Strategy and Structure; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1962; ISBN 9780262030045. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, S.; Liu, C.; Min, M.; Zhou, L. Fit between Organizational Culture and Innovation Strategy: Implications for Innovation Performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasic, B.; Stenz, B. Taken for a Ride: How Daimler-Benz Drove off with Chrysler; William Morrow & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0688173055. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Redvers Opie: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934; ISBN 9780674879904. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, C.Y.; Dunkelberg, W.C.; Cooper, A.C. Entrepreneurial Typologies: Definition and Implications. Front. Entrep. Res. 1988, 8, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, H. Captain of Industry. Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences, III; MacMillan and Co. LTD: London, UK, 1909; pp. 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, M. Information and Organization: A New Perspective on the Theory of the Firm; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1997; ISBN 0198297807. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, J.W. Survey of the Evidence and Findings on Mergers in Business Concentration and Price Policy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1955; ISBN 0870141961. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaki, A.; Tarba, S.; Ahammad, M.F.; Glaister, A.J. The moderating role of transformational leadership on HR practices in M&A integration. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2016, 27, 2488–2504. [Google Scholar]

- Westerman, G.H.; Grandy, T.G.; Combs, C.G.; Turner, C.H. Personality Variables as Predictors of Performance for First-year Dental Students. J. Dent. Educ. 1989, 53, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K.M.; Johnson, W.B. Personality Type and Success among Female Naval Academy Midshipmen. Mil. Med. 2001, 166, 10–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuit, D.P. At 60, Myer-Briggs Is Still Sorting Out and Identifying People’s Types. Workforce Manag. 2003, 72–74. Available online: https://www.workforce.com/2003/11/26/at-60-myers-briggs-is-still-sorting-out-and-identifying-peoples-types/ (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Lewin, K. A Dynamic Theory of Personality; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, M. Lucent and Alcatel: A Merger by any other Name is an Acquisition. USA Today. Available online: www.usatoday.com (accessed on 25 October 2006).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).