Green to Gold: Beneficial Impacts of Sustainability Certification and Practice on Tour Enterprise Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Effects that Sustainability Practices Have on Financial and Non-Financial Firm Performance

“Travelers are coming to expect that tourism businesses will become sustainable in the same way they expect free Wi-Fi connectivity in hotels or online check-in for air travel.”

3. Methodology of the Study

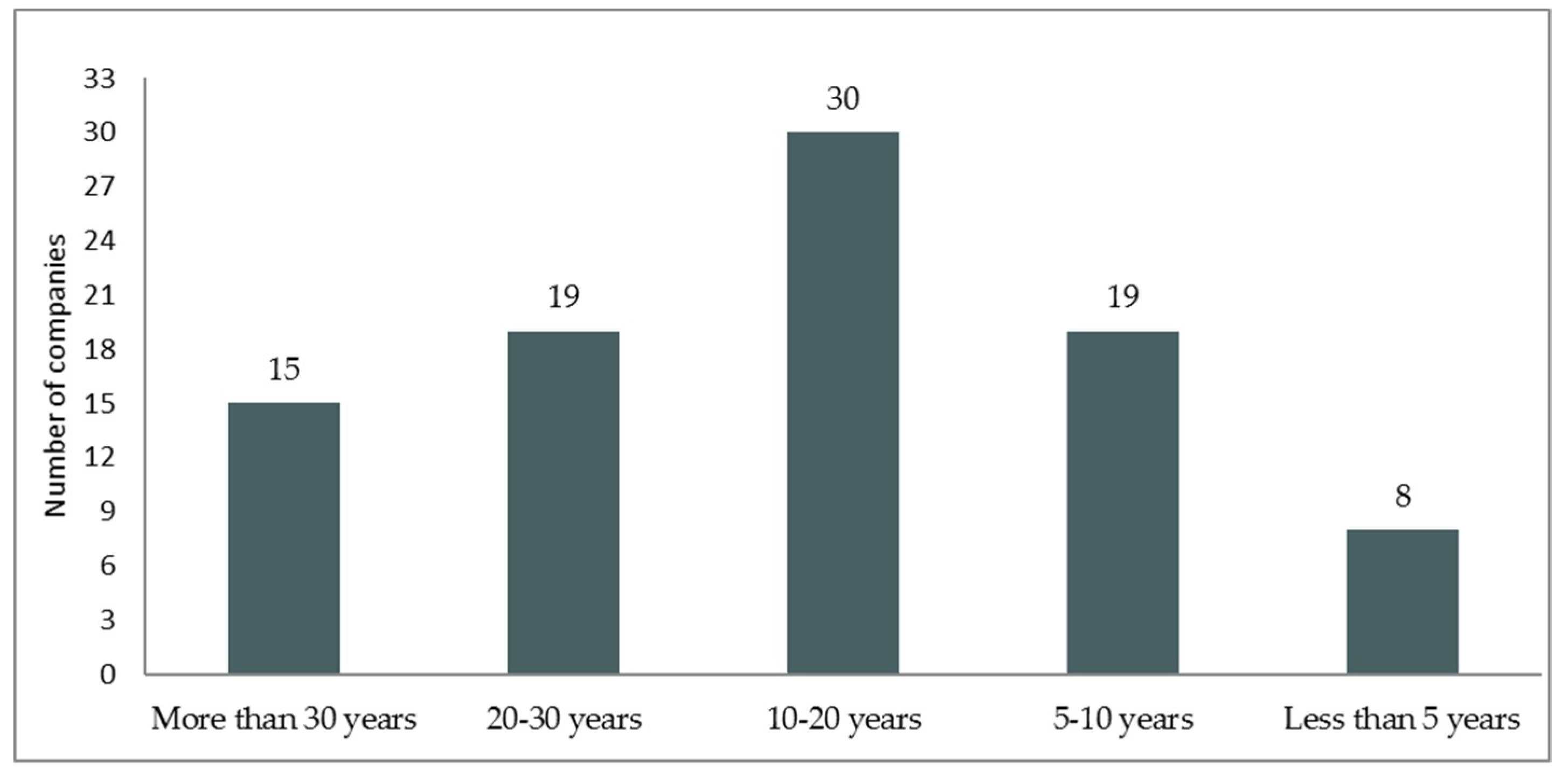

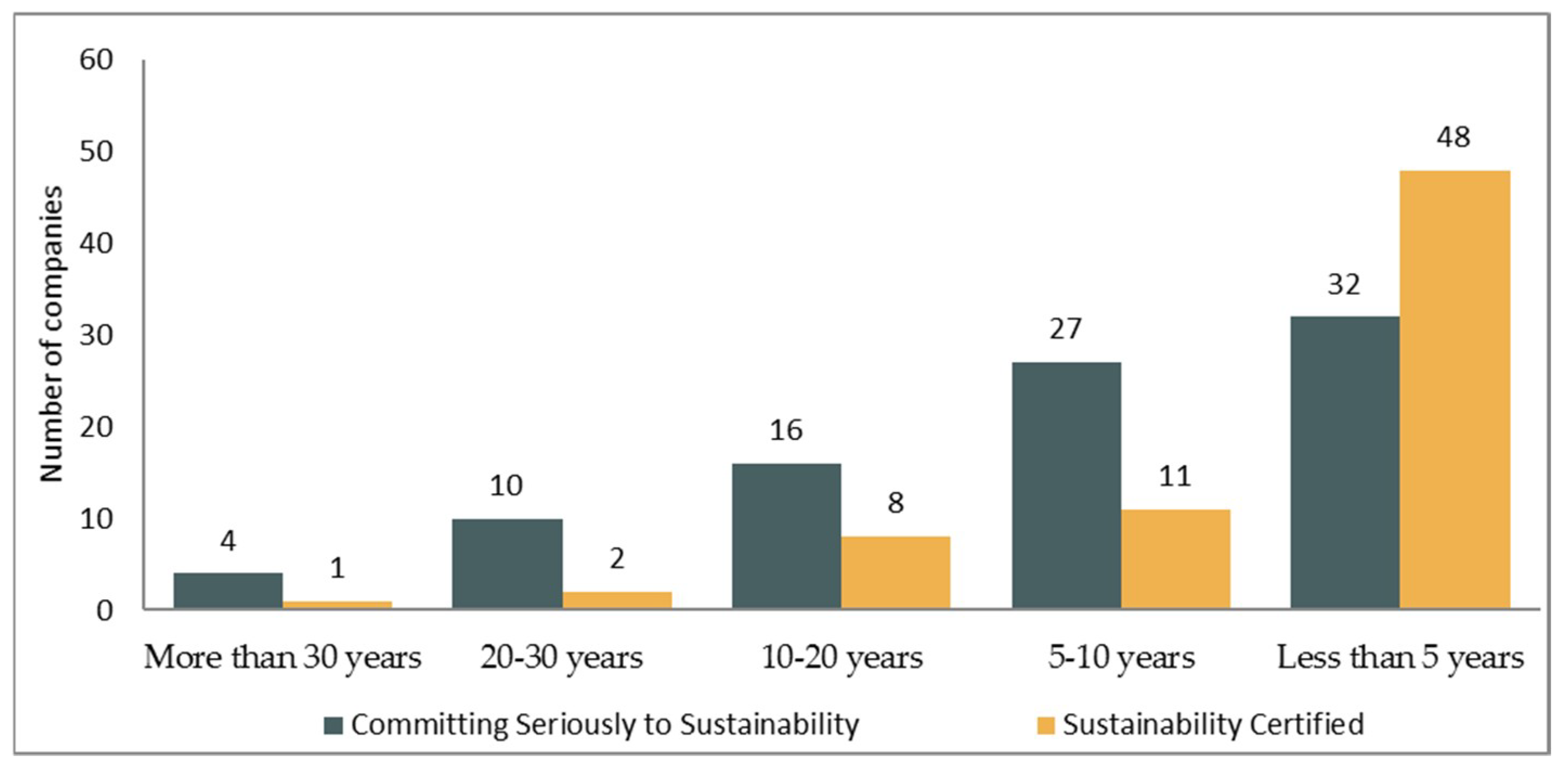

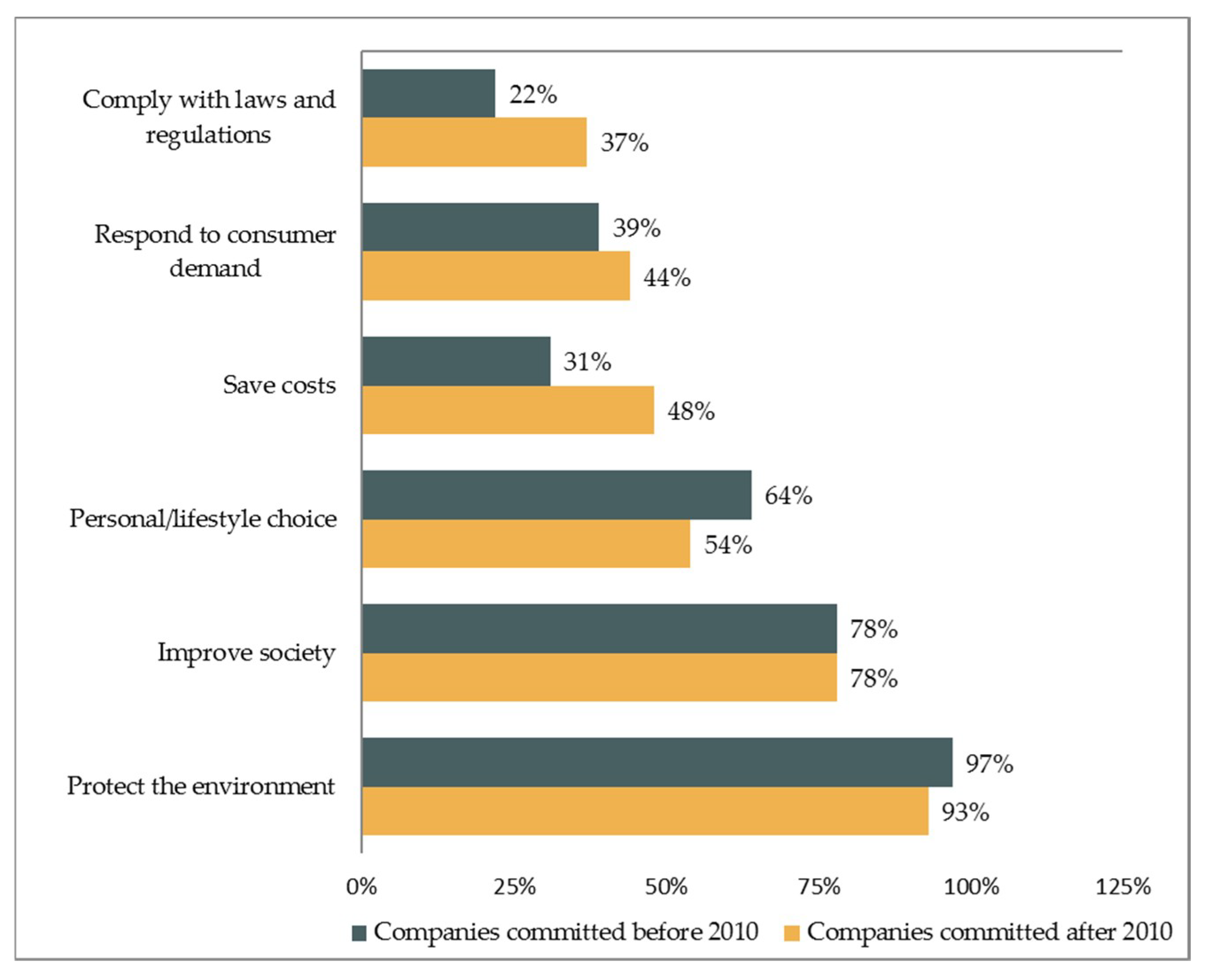

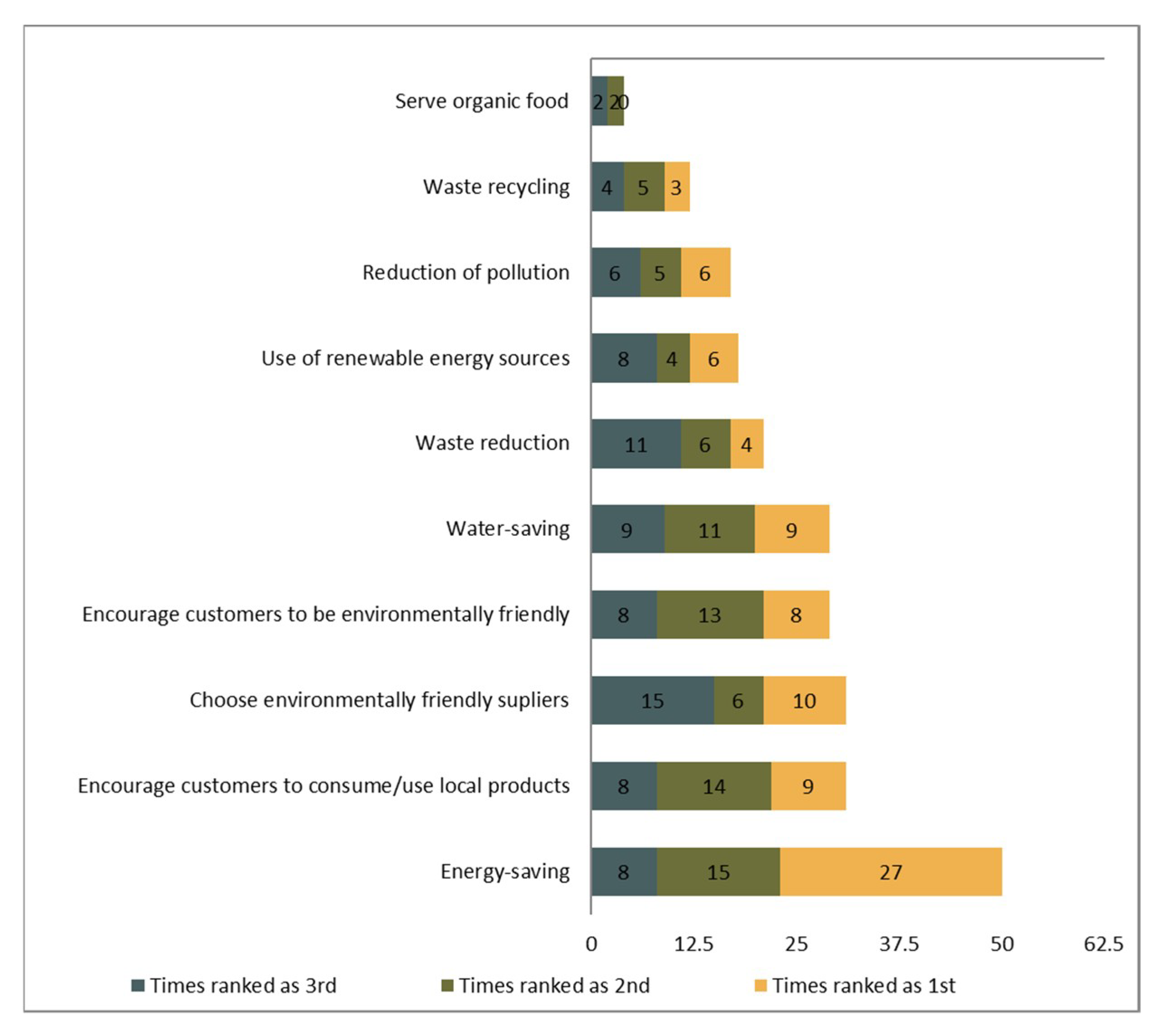

4. Results of the Exploratory Study

An additional influencing factor on customer numbers and spending on sustainable tours has been identified as customer age & origin. The study reviewed whether there were differences in motivational influence based on these factors and found no significant difference.“Protection of wildlife”“Thailand doesn’t have very many eco-laws, so we make our own.”“For now a good marketing tool, but in a few years we believe that without a sustainability certificate we are out of the market.”“It is all about bringing awareness to people.”

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Carasuk, R.; Becken, S.; Hughey, K.F. Exploring values, drivers, and barriers as antecedents of implementing responsible tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Garay, L.; Jones, S. Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaugeois, N.; Goodwin, B.; Thuot, L.; Sliskovic, L.E.; Simmonds, G.; Whitney-Squire, K.F.; Faktor, A.; Young, J.; Simpson, T.; Borton, S.; et al. Made in BC: Innovation in Sustainable Tourism. Fostering Innovation in Sustainable Tourism. 2009. Available online: https://web.viu.ca/sustainabletourism/Innovation%20manual%20Final%20June%204.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the global hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, A.; Stokes, D.; Chen, H. Small businesses and the environment: Turning over a new leaf? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bonini, S.; Bové, A.-T. Sustainability’s Strategic Worth: McKinsey Global Survey Results; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability-and-resource-productivity/our-insights/sustainabilitys-strategic-worth-mckinsey-global-survey-results (accessed on 2 July 2017).

- Dickinson, J.E.; Robbins, D.; Lumsdon, L. Holiday Travel Discourses and Climate Change. J. Transport Geogr. 2010, 18, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Rathouse, K.; Scarles, C.; Holmes, K.; Tribe, J. Public understanding of sustainable tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 2010, 37, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Cohen, S.A.; Cavaliere, C.T.; Reis, A.C.; Finkler, W. Climate change, tourist air travel and radical emissions reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Peeters, P.; Scott, D. The Future of Tourism: Can Tourism Growth and Climate Policy be Reconciled? A Mitigation Perspective. Tourism Recreation Res. 2010, 35, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Degrowing Tourism: Décroissance, Sustainable Consumption and Steady-State Tourism. Anatolia 2009, 20, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S.R.; Holmes, M. Does the tourist care? A comparison of tourists in Koh Phi Phi, Thailand and Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Larsen, S. Attitudes, efficacy beliefs, and willingness to pay for environmental protection when travelling. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 15, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Kazeminia, A.; Ghasemi, V. Intention to visit and willingness to pay premium for ecotourism: The impact of attitude, materialism, and motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.; Cheung, O.; Jim, C.Y. Expectations and willingness-to-pay for ecotourism services in Hong Kong’s conservation areas. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pengwei, W.; Linsheng, Z. Tourist Willingness to Pay for Protected Area Ecotourism Resources and Influencing Factors at the Hulun Lake Protected Area. J. Resour. Ecol. 2018, 9, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Banking and Finance: Non-Financial Reporting; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/finance/company-reporting/non-financial_reporting/index_en.htm (accessed on 31 January 2017).

- Dendler, L. Sustainability Meta Labelling: An effective measure to facilitate more sustainable consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1. Available online: http://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 7 November 2018).

- Armstrong, J.S.; Green, K.C. Effects of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility policies. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1922–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Lee, S.; Huh, C. Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 21, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M. Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.H.; Chang, Y. Ambition versus conscience, does corporate social responsibility pay off? The application of matching methods. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, D.C.; Winston, A. Green to Gold: How Smart Companies Use Environmental Strategy to Innovate, Create Value, and Build Competitive Advantage; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, D.; Turban, D. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; Tarí, J.J. Environmental practices and firm performance: An empirical analysis in the Spanish hotel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S.; Dodds, R. Why Go Green? The Business Case for Environmental Commitment in the Canadian Hotel Industry. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 19, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, E.; Habisch, A.; Pechlaner, H. Values that create value: Socially responsible business practice in SMEs: Empirical evidence from German companies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortés, E.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D. Environmental strategies and their impact on hotel performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.; Ricaurte, E. Hotel sustainability benchmarking. Cornell Hosp. Rep. 2014, 14, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aznar, J.P.; Sayeras, J.M.; Galiana, J.; Rocafort, A. Sustainability Commitment, New Competitors’ Presence, and Hotel Performance: The Hotel Industry in Barcelona. Sustainability 2016, 8, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Rosenthal, S. Signaling the Green Sell: The Influence of Eco-Label Source, Argument Specificity, and Product Involvement on Consumer Trust. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makower, J.; Pike, C. Strategies for the Green Economy: Opportunities and Challenges in the World of Business; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Sustainable Tourism at East Carolina University. (n.d.). 10 Low to No-Cost Green Practices You Can Implement Today. Von Center for Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://www.ecu.edu/cs-acad/sustainabletourism/upload/10-Sustainable-Practices-You-can-Implement-Today.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Federation of Tour Operators. Travelife Sustainability Handbook. Travelife: Sustainability in Tourism. 2006. Available online: http://www.travelife.org/tourism_business_new/documents/Supplier_Sustainability_Handbook_English.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Kakaley, A.; Volkman, J.; Weaver, B.L. No-Cost/Low-Cost Energy Savings Guide; IFMA Foundation: Houston, TX, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.fmi.gov/sites/default/files/NoCostLowCostGuide.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Reichel, A.; Haber, S. Identifying Performance Measures of Small Ventures: The Case of the Tourism Industry. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 257–287. [Google Scholar]

- Akbaba, A. Business performance of small tourism enterprises: A comparison among three sub-sectors of the industry. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 23, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBusk, S. Hotels Install Window Film to Increase Energy Efficiency. 2015. Available online: https://www.llumar.com/window-film-blog/commercial-window-film-blog-llumar/hotels-install-window-film-to-increase-energy-efficiency (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Esty, D.C.; Simmons, P.J. The Green to Gold Business Playbook: How to Implement Sustainability Practices for Bottom-line Results in Every Business Function; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brebbia, C.A.; Pineda, F.D. Sustainable Tourism; WIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Budeanu, A. Impacts and responsibilities for sustainable tourism: A tour operator’s perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum for the Future and The Travel Foundation. Survival of the Fittest: Sustainable Tourism Means Business; Forum for the Future and The Travel Foundation: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- TripAdvisor. Tripadvisor Survey Revelas Travelers Growing Greener; TripAdvisor: Needham, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.multivu.com/mnr/49260-tripadvisor-eco-friendly-travel-survey-voluntourism-go-green (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Kwan, H.; Liu, H.; Mak, H. Willingness to Pay for Responsible Travel; Ryerson University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Adlwarth, W. Corporate Social Responsibility—Customer Expectations and Behaviour in the Tourism Sector: Trends and Issues in Global Tourism; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- López-Sánchez, Y.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. In search of the pro-sustainable tourist: A segmentation based on the tourist “sustainable intelligence”. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Travel & tourism 2015: Connection Global Climate Action; World Travel & Tourism Council: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Makower, J. Green Marketing Is Over. Let’s Move On; Greenbiz: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011; Available online: http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2011/05/16/ green-marketing-over-lets-move?page=full (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Crane, A. Marketing and the Natural Environment: What Role for Morality. J. Macromarketing 2000, 20, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leire, C.; Thidell, Å. Product-related environmental information to guide consumer purchases—A review and analysis of research on perceptions, understanding and use among Nordic consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green marketing: Legend, myth, farce or prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Buckley, R. Carbon labels in tourism: Persuasive communication? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Elgammal, I.; Lamond, I. Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived Greenwashing: The Interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental Performance on Consumer Reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarino, J.; Font, X. Sustainability marketing myopia: The lack of persuasiveness in sustainability communication. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 8, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A. The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools, and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, G.; Font, X.; Nawijn, J. The power of persuasive communication to influence sustainable holiday choices: Appealing to self-benefits and norms. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Kim, D.Y. The effects of message framing and source credibility on green messages in hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford, E.R.; Hartman, C.L. Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Nairn-Birch, N.; Balzarova, M. Choosing the right eco-label for your product. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2013, 4, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Big Room Inc. Ecolabel Index. 2017. Available online: http://www.ecolabelindex.com (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Hamele, H. DestiNet: Mehr Transparenz im nachhaltigen Tourismus. In Tourismus in Entwicklungs- und Schwellenländer; (S. 239–240); Studienkreis für Tourismus und Entwicklung: Seefeld, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M.J. CBSR Blog: CSR as a Driver of Employee Engagement; 3BL Media: Northampton, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://3blmedia.com/theCSRfeed/CBSR-Blog-CSR-Driver-Employee-Engagement (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Wirtenberg, J. Building a Culture for Sustainability: People, Planet, and Profits in a New Green Economy; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Society for Human Resource Management. Advancing Sustainability: HR’s Role: A Research Report by the Society for Human Resource Management, BSR and Aurosoorya; Society for Human Resource Management: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano, D.F. Corporate social responsibility and labor turnover. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2010, 10, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, Careers, and Callings: People’s Relations to Their Work. J. Res. Pers. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A. Finding Positive Meaning in Work. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, M.A.; Pekovic, S. Environmental standards and labor productivity: Understanding the mechanisms that sustain sustainability. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, L.; Stanciu, O.; Țichindelean, M.; Vinerean, S. Achieving employee satisfaction by pursuing sustainable practices. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2013, 8, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Watch. A Guide through the Tourism Label Jungle. 2016. Available online: https://www.tourism-watch.de/en/content/guide-through-tourism-label-jungle (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Dunphy, D.; Griffiths, A.; Benn, S. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the hospitality industry: Some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nielsen Company. Consumer-Goods’ Brands That Demonstrate Commitment to Sustainability Outperforme Those That Don’t; Nielsen: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.nielsen.com/ca/en/press-/room/2015/consumer-goods-brands-that-demonstrate-commitment-to-sustainability-outperform.html (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Kachel, U.; Jennings, G. Exploring tourists’ environmental learning, values and travel experiences in relation to climate change: A postmodern constructivist research agenda. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hellmeister, A.; Richins, H. Green to Gold: Beneficial Impacts of Sustainability Certification and Practice on Tour Enterprise Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030709

Hellmeister A, Richins H. Green to Gold: Beneficial Impacts of Sustainability Certification and Practice on Tour Enterprise Performance. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030709

Chicago/Turabian StyleHellmeister, André, and Harold Richins. 2019. "Green to Gold: Beneficial Impacts of Sustainability Certification and Practice on Tour Enterprise Performance" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030709

APA StyleHellmeister, A., & Richins, H. (2019). Green to Gold: Beneficial Impacts of Sustainability Certification and Practice on Tour Enterprise Performance. Sustainability, 11(3), 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030709