The Socio-educational, Psychological and Family-Related Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Spanish Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Betancor, M.V. Empoderamiento: Una alternativa emancipatoria? Reflexiones para una aproximación crítica a la noción de empoderamiento. Trab. Soc. Cienc. Soc. 2011, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Palmero, A.; Palmero-Cámara, C.; Jiménez-Eguizábal, A. El impacto de la educación secundaria y superior en la creación de empresas en la Unión Europea. Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2012, 252, 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Luis, M.I.; Palmero, C.; Escolar, M.C. Impacto de la educación en el emprendimiento. Making-of y análisis de tres grupos de discusión. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. PSRI 2015, 25, 221–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.J. Emprendimiento, Iniciativa y Creatividad. In Cómo ser Competente. Competencias Profesionales Demandadas en el Mercado Laboral; Servicio de Inserción Profesional Practicas y Empleo: Salamanca, Spain, 2013; pp. 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M.; Fuentes, M.M.; Ruiz, J. Análisis del emprendedor potencial: Integración de cognitivos y relacionales. AJOICA 2014, 12, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, G.; Soukiazis, E., II. The determining factors of entrepreneurship in Portugal. Rev. Gestão Países Língua Port. 2015, 14, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, A.M.; Pérez, M.I.; Palma, M.; López, M.C. Emprendimiento: Visión actual como disciplina de investigación. Un análisis de los números especiales publicados durante 2011–2013. Estud. Geren. 2016, 32, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toca, C. Consideraciones para la formación en emprendimiento: Explorando nuevos ámbitos y posibilidades. Estud. Geren. 2010, 26, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.C. Entrepreneurship as a legitimate field of knowledge. Psicothema 2011, 23, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Torres, F.; Artigas, W. Emprendimiento económico: Elementos teóricos desde las perspectivas de sistemas y redes. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2015, 21, 429–441. [Google Scholar]

- Dau, L.A.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A. To formalize or not to formalize: Entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, A.; Thurik,, A.R. Entrepreneurship and its determinants in a cross-country setting. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.; Thurik, R. Postmaterialism influencing total entrepreneurial activity across nations. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Summary Report. The Public Debate Following the Green Paper “Entrepreneurship in Europe”; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. Shaping of Competencies of Managers in Academic Incubators of Entrepreneurship in Poland. Organizacija 2014, 47, 52–65. Available online: http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/orga.2014.47.issue-1/orga-2014-0005/orga-2014-0005.xml (accessed on 23 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- Johansen, V. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial activity. In Proceedings of the IntEnt 2007–17th Global Conference, Internationalizing Entrepreneurship Education and Training, Gdansk, Poland, 8–11 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- do Paço, A.M.F.; Ferreira, J.M.; Raposo, M.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Dinis, A. Behaviours and entrepreneurial intention: Empirical findings about secondary students. J. Int. Entrep. 2011, 9, 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kourilsky, M.L.; Walstad, W.B. Entrepreneurship and female youth: Knowledge, attitudes, gender differences and educational practices. J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lim, S.; Pathank, R. Influences on students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship: A multi-country study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2006, 2, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Audretsch, D.B.; Sarkar, M.B. The process of creative construction: Knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J.; Strom, R.J. Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Amorim Neto, R.C.; Rodrigues, V.P.; Stewart, D.; Xiao, A.; Snyder, J. The influence of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial behavior among K-12 teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 72, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. The Free-Market Innovation Machine: Analyzing the Growth Miracle of Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D. How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam, K.; Schipper, M.; Runhaar, P. Developing a competency-based framework for teachers’ entrepreneurial behaviour. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriano, J.A.; Palací, F.J.; Morales, J.F. El perfil psicosocial del emprendedor universitario. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2006, 22, 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Hermel, P.; Srivatava, A. Entrepreneurial intentions—theory and evidence from Asia, America, and Europe. J. Int. Entrep. 2017, 15, 324–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Aponte, E.; Arias-Gómez, D. Intención emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios: Integración de factores cognitivos y socio-personales. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Soc. 2015, 6, 320–340. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, I.; Valencia, A.; Montoya, A. Mapeo del campo de conocimiento en intenciones emprendedoras mediante el análisis de redes sociales de conocimiento. Ingeniare Rev. Chil. Ing. 2016, 24, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.A.; Prieto, F.A. La sensibilidad al emprendimiento en los estudiantes universitarios. Estudio comparativo Colombia-Francia. Innovar. Rev. Cienc. Admin. Soc. 2009, 19, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 25, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanero, A.; Vazquez, J.L.; Munoz-Adanez, A. A social cognitive model of entrepreneurial intentions in university students. Anal. Psicol. Spain 2015, 31, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.C.; Aldana, R.; de Dios, S.; Yurrebaso, A. La intención emprendedora como elección de carrera. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 4, 543–552. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.C.; Lanero, A.; Yurrebaso, A. Variables determinantes de la intención emprendedora en el contexto universitario. Rev. Psicol. Soc. Apl. 2005, 15, 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B.; Lassas-Clerc, N. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2006, 30, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maija, A.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentios in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar]

- Dheer, R.J.S.; Lenartowicz, T. Multiculturalism and Entrepreneurial Intentions: Understanding the Mediating Role of Cognitions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 426–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A. Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 692–701. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras Torres, F.; Espinosa Méndez, J.C.; Soria Barreto, K.; Portalanza Chavarría, A.; Jáuregui Machuca, K.; Omaña Guerrero, J.A. Exploring entrepreneurial intentions in Latin American university students. Int J Psychol. Res. 2017, 10, 46–59. Available online: http://revistas.usb.edu.co/index.php/IJPR/article/view/2794 (accessed on 6 June 2018). [CrossRef]

- Do, B.-R.; Dadvari, A. The influence of the dark triad on the relationship between entrepreneurial attitude orientation and entrepreneurial intention: A study among students in Taiwan University. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 185–191. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1029313216304249?via%3Dihub (accessed on 30 May 2018). [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Akhtar, F.; Das, N. Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Tarapuez, E.; García, M.D.; Castellano, N. Aspectos socioeconómicos e intención emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios del Quindío (Colombia). Innovar 2016, 28, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2008, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Walmsley, A.; Liñán, F.; Akhtar, I.; Neame, C. Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Stud. High Educ. 2018, 43, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanero, A.; Vázquez, J.L.; Gutiérrez, P.; García, M.P. Evaluación de la conducta emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios. Implicaciones para el diseño de programas académicos. Pecvnia 2011, 12, 219–243. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1288085776?accountid=12268 (accessed on 13 May 2018). [CrossRef]

- Schaub, M.; Tokar, D.M. The role of personality and learning experiences in Social Cognitive Career Theory. J. Voc. Behav. 2005, 66, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. OB and Entrepreneurship: The reciprocal benefits of closer conceptual links. In Research in Organizational Behavior—An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews; Staw, B.M., Kramer, R.M., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 225–270. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfelt, J.; Kotter, J.P. The maturation of career theory. Hum. Relac. 1982, 35, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J. A psychological cognitive model of employment status choice. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 17, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The social dimensions of enterpreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Entreprenurial Mind; Kent, C., Sexton, D., Vesper, K.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Regmi, K.D. Lifelong learning: Foundational models, underlying assumptions and critiques. Int. Rev. Educ. 2015, 61, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A. Competencia emprendedora e identidad personal. Una investigación exploratoria con estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Educ. 2014, 363, 384–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A. Entrepreneurship pedagogies in lifelong learning: Emergence of criticality? Learn. Cult. Social Interact. 2015, 6, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Barreto, K.; Zuniga-Jara, S.; Ruiz-Campo, S. Educación e Intención Emprendedora en Estudiantes Universitarios: Un Caso de Estudio. Form Univ. 2016, 9, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Martínez, A.; Fernández, R. Características del emprendedor influyentes en el proceso de creación empresarial y en el éxito esperado. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2010, 19, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, P.; Welsh, D.; Bushmarin, N. Locus of Control and Entrepreneurship in the Russian Republic. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1995, 20, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Kolvereid, L.; Westhead, P. An Exploratory Examination of the Reasons Lea- ding to New Firm Formation Across Country and Gender. J. Bus. Ventur. 1991, 6, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; Van den Broeck, H.; Cools, E.; Vanderheyden, K. In Search for the Heffalump: An Exploration of the Cognitive Style Profiles among Entrepreneurs; Vlerick Leuven Gent Management School Working Paper Series-4; Vlerick Leuven Gent Management School: Vlerick, Brussels, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neri, J.L.; Watson, W. An examination of the relationship between manager self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions and performance in Mexican small businesses. Contad. Admin. 2013, 58, 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R. Marketing; Barrons: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis of the relationship between business owners’ personality characteristics and business creation and success. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.; Langan-Fox, J.; Grant, S. Entrepreneurship research and practice: A call to action for psychology. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Busenitz, L.; Lant, T.; McDougall, P.P.; Morse, E.A.; Smith, J.B. Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; West, G.P., III; Shepherd, D.; Nelson, T.; Chandler, G.N.; Zacharakis, A. Entrepreneurship research in emergence: Past trends and future directions. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.A. Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs «connect the dots» to identify new business opportunities. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, B.; Kaish, S.; Ronen, J. The entrepreneurial way with information. In Applied Behavioral Economics; Maital, S., Ed.; Wheatsheaf Books: Brighton, UK, 1988; pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Voc. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupani, M.; Azpilicueta, A.E.; Sialle, V. Evaluación de un modelo social-cognitivo de la elección de la carrera desde la tipología de Holland en estudiantes de la escuela secundaria. REOP Rev. Española Orientación Psicopedag. 2017, 28, 8–24. Available online: http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/reop/article/view/21615/17821 (accessed on 6 June 2018). [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Social cognitive career theory and subjective well-being in the context of work. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.C. The measurement of vocational interests: Issues and future directions. In Handbook of Counseling Psychology; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: Nueva York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Rodermund, E.; Vondracek, F.W. Occupational dreams, choices and aspirations: Adolescents’ entrepreneurial prospects and orientations. J. Adol. 2002, 25, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, E.; Schmitt-Rodermund, E. Crystallizing enterprising interests among adolescents through a career development program: The role of personality and family background. J. Voc. Behav. 2006, 69, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. On Lines and Planes of Closest Fit to Systems of Points in Space. Philos. Mag. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, W.; Hishamuddin, B.I. Revisiting personality traits in entrepreneurship study from resource-based per- spective. Bus. Ren. Q. 2008, 3, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Laviada, A. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Informe GEM España 2015; Universidad de Cantabria: Cantabria, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez de Luco, G.A.; Campos, J.A. La intención emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios: El caso de la Universidad de Deusto. Bol. Estud. Econ. 2014, 69, 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P.D.; Hay, M.; Bygrave, W.D.; Camp, S.M.; Autio, E. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Executive Report. 2000. Available online: http://www.gemconsortium.org (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- Delgado, M.I.; Gómez, L.; Romero, A.M.; Vázquez, E. Determinantes sociales y cognitivos en el espíritu emprendedor: Un estudio exploratorio entre estudiantes argentinos. Cuaderno Gestión. 2008, 8, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Drennan, J.; Kennedy, J.; Renfrow, P. Impact of childhood experiences on the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Entrepren. Innov. 2005, 6, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marino, D. Gender, Entrepreneurial Self Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíritu, R. Análisis de la intención emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios a través de los rasgos de personalidad. Multiciencias 2011, 11, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gürol, Y.; Atsan, N. Entrepreneurial characteristics amongst university students: Some insights for entrepreneurship education and training in Turkey. Educ. Train. 2006, 48, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Álvarez, J.; Pedrosa, I. Evaluación de la personalidad emprendedora: Situación actual y líneas de futuro. Pap. Psicól. 2016, 37, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Lumpkin, G.T. The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2010, 367, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, F.; Sánchez, S.M. Análisis del perfil emprendedor: Una perspectiva de género. Estud. Econ. Aplic. 2010, 28, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.M.; Gartner, W.B.; Shaver, K.G.; Gatewood, E.J. The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, R.; Neergard, H.; Kirketerp, A. Self-efficacy: Conditioning the Entreprenurial Mindset. In Understanding the Entreprenurial Mind; Carsrud, A.L., Brännback, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 233–358. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Entrepreneurship Flash Eurobarometer 134; Directorate General Enterprises: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.C. Evaluación de la personalidad emprendedora: Validez factorial del cuestionario de orientación emprendedora (COE). Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2010, 42, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J. Are Nascent Entrepreneurs Jacks-of-all-Trades? A Test of Lazear´s Theory of Entrepreneurship with German Data. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 2415–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

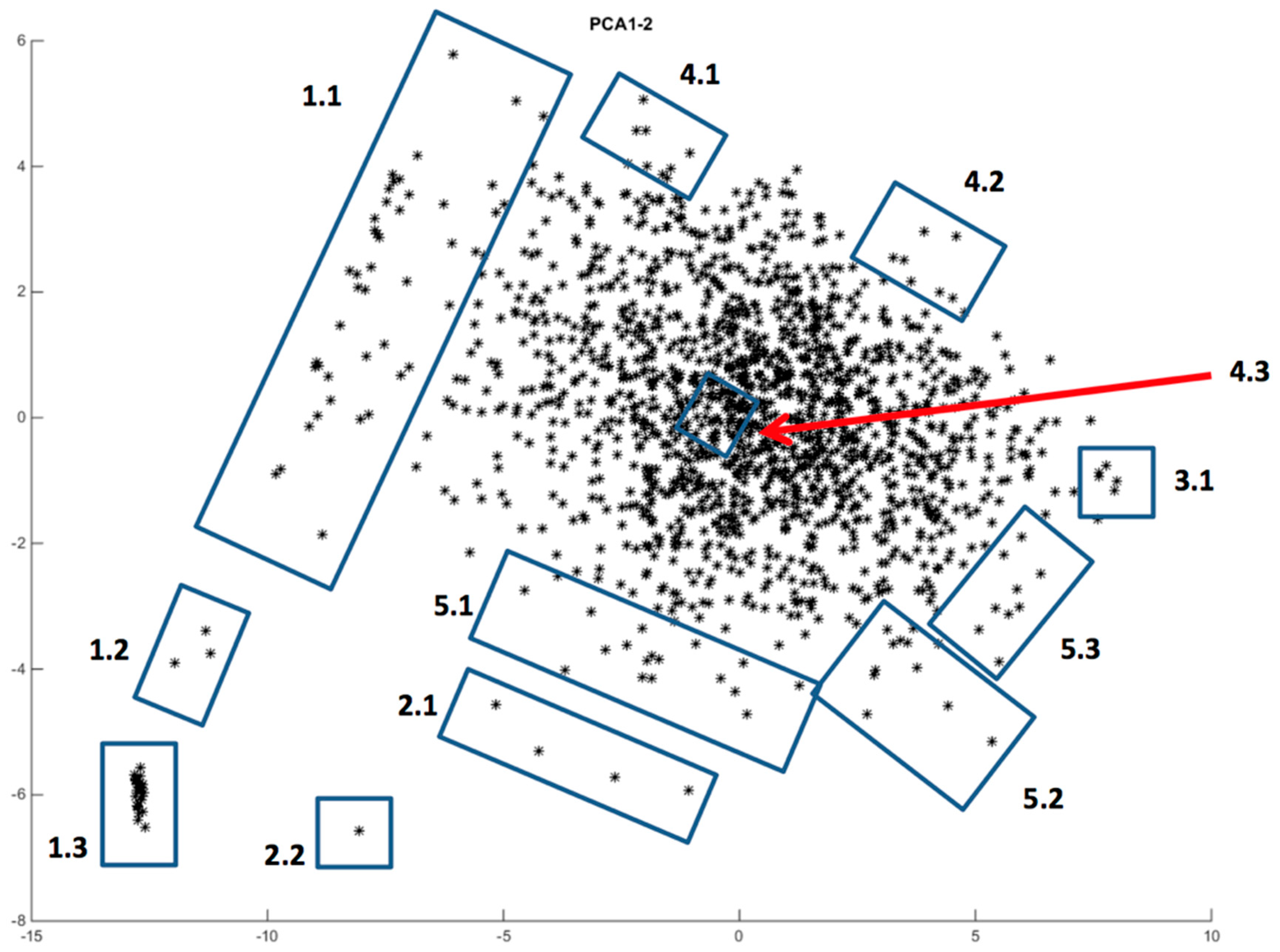

| PCA Group | Average Entrepreneurial Interest | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 2.13 | 47 |

| 1.2 | 1.76 | 3 |

| 1.3 a | 1 | 25 |

| 2.1 | 1.5 | 4 |

| 2.2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3.1 | 2.6 | 5 |

| 4.1 | 3.22 | 9 |

| 4.2 | 4 | 8 |

| 4.3 b | 2.5 | 30 |

| 5.1 | 3 | 18 |

| 5.2 | 3.08 | 12 |

| 5.3 | 3 | 9 |

| Total number of participants | 171 |

| PCA Group | Average Entrepreneurial Interest | Number of Participants | Average Global Entrepreneurial Interest of the PCA Groups | Total Number of Participants in the PCA Groups (146 Students) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High entrepreneurial interest groups a | 4.1 | 3.22 | 8 | ||

| 4.2 | 4 | 9 | |||

| 3.1 | 2.6 | 12 | |||

| 5.3 | 3 | 18 | |||

| 5.2 | 3.08 | 9 | |||

| 5.1 | 3 | 5 | |||

| 3.10 | 61 (41.8%) | ||||

| Low entrepreneurial interest groups | 4.3 | 2.5 | 30 | ||

| 1.1 | 2.13 | 47 | |||

| 1.2 | 1.67 | 3 | |||

| 2.1 | 1.5 | 4 | |||

| 2.2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1.59 | 85 (58.2%) |

| High Entrepreneurial Interest Group | Low Entrepreneurial Interest Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Women | 38% | 41% |

| Men | 62% | 59% | |

| Education of parents | None | 12% | 2% |

| Primary | 0% | 8% | |

| Secondary | 72% | 87% | |

| Higher | 16% | 3% | |

| Education of mother | None | 6% | 3% |

| Primary | 19% | 3% | |

| Secondary | 69% | 89% | |

| Higher | 6% | 5% | |

| Employment of father | Employment contract | 12% | 45% |

| Self-employed | 37% | 22% | |

| House husband | 0% | 0% | |

| Unemployed | 25% | 11% | |

| Retired | 13% | 11% | |

| Pensioner | 13% | 11% | |

| Employment of mother | Employment contract | 23% | 50% |

| Self-employed | 14% | 37% | |

| House wife | 27% | 0% | |

| Unemployed | 27% | 0% | |

| Retired | 4% | 0% | |

| Pensioner | 5% | 13% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escolar-Llamazares, M.C.; Luis-Rico, I.; de la Torre-Cruz, T.; Herrero, Á.; Jiménez, A.; Palmero-Cámara, C.; Jiménez-Eguizábal, A. The Socio-educational, Psychological and Family-Related Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Spanish Youth. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051252

Escolar-Llamazares MC, Luis-Rico I, de la Torre-Cruz T, Herrero Á, Jiménez A, Palmero-Cámara C, Jiménez-Eguizábal A. The Socio-educational, Psychological and Family-Related Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Spanish Youth. Sustainability. 2019; 11(5):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051252

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscolar-Llamazares, M. Camino, Isabel Luis-Rico, Tamara de la Torre-Cruz, Álvaro Herrero, Alfredo Jiménez, Carmen Palmero-Cámara, and Alfredo Jiménez-Eguizábal. 2019. "The Socio-educational, Psychological and Family-Related Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Spanish Youth" Sustainability 11, no. 5: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051252

APA StyleEscolar-Llamazares, M. C., Luis-Rico, I., de la Torre-Cruz, T., Herrero, Á., Jiménez, A., Palmero-Cámara, C., & Jiménez-Eguizábal, A. (2019). The Socio-educational, Psychological and Family-Related Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions among Spanish Youth. Sustainability, 11(5), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051252