CSR Maturity in Polish Listed Companies: A Qualitative Diagnosis Based on a Progression Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Which level of CSR maturity—incidental, tactical or strategic—is presented by the companies in Poland covered by the study?

- What is the distribution of CSR maturity in the studied population and does the CSR maturity depend on a company’s size and industry?

- What is the level of CSR process maturity, CSR formal maturity and CSR developmental maturity, and what practices do the studied enterprises present?

2. Recent History of CSR in Poland–Institutional Context

- The first stage of CSR development in Poland (1989–1999) can be described as a phase of silence and lack of interest [34].

- In the second stage (2000–2002), CSR raised dislike and sometimes even opposition from many business leaders and economic columnists, overwhelmed by the idea of “the invisible hand of the market” as a cure-all therapy [34].

- The third stage (2003–2004) brought interest in declaring recognition of ethics and social responsibility as a foundation of a company’s conduct [34].

- The fourth stage (2004–2005) concerned the development of specific, albeit partial projects, involving certain significant areas of a company’s functioning [34].

- The fifth stage (2006–2007) was an attempt to link CSR with other strategies implemented in a company, i.e., communications, personnel, marketing or corporate governance strategy [34].

- The sixth stage (2007-now) is of advanced implementation when managers of large and medium companies try to adapt their activities to standards observed in Western practices [35].

3. Developing CSR in Enterprises

3.1. CSR Determinants

3.2. Progression Models of CSR

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. CSR Maturity–Conceptual Model

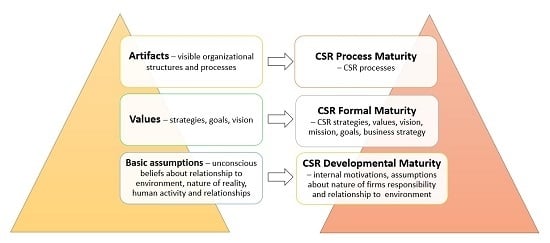

- The CSR maturity can be analyzed at three levels: the level of artifacts, of espoused values and of basic assumption (Figure 2).

- Artifacts will refer to visible processes through which the enterprise conducts CSR activity. The CSR process maturity will be the measured construct.

- Espoused values will refer to CSR commitments as present in companies’ fundamental formal documents, such as strategies, reports, value declarations, mission statements, goals and philosophies. CSR formal maturity will be the measured construct.

- Basic underlying assumptions will refer to the company’s motivation for CSR behavior and beliefs that the company has about the nature of the firm’s responsibility towards the environment. CSR developmental maturity will be the measured construct.

- CSR maturity is reflected in the CSR process, the formal and developmental maturity. A higher maturity of practices in each of the three perspectives means a more advanced CSR implementation in the organization.

- The CSR maturity score allows qualifying the enterprise as using strategic, tactical or incidental CSR.

4.2. Methods and Sample

- Companies’ mission statements

- Codes of ethics

- Corporate governance declarations

- CSR reports and other CSR practice reports

- CSR strategies and other CSR practice declarations

- Prizes awarded to enterprises and membership in organizations

- Management systems implemented in companies

- Business strategies.

- Listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange since at least 2007.

- Represented nine sectors: construction, chemistry, developers, energy, IT, media, food, telecommunication, and banking.

- Listed in WIG industry indexes (between 2007 and 2013 continuously). The CSR maturity evaluation of enterprises in Poland was part of a larger research project covering also financial variables not used in this article and gathered between 2007 and 2013. The sample comprised of companies listed continuously in WIG industry indexes in this period.

4.3. Measures: 3 Perspectives of CSR Maturity

4.3.1. CSR Process Maturity Measure

- Level 1: Initial: The process has not been identified yet, the actions are chaotic and ad hoc. The roles, duties and resources are not clearly specified yet.

- Level 2: Repeatable: The process is stabilized and repeatable. It creates predictable results, although it has not been formalized yet. Project management is implemented; budgeting and schedules are used.

- Level 3: Defined: The process has been defined and documented, roles were distributed, and resources were assigned. Specific codes of conduct and procedures have been developed.

- Level 4: Managed: measures (of effectiveness, quality, etc.) are used; the process is aimed at achieving company goals; it is strictly monitored and reported on an ongoing basis. The process is analyzed, and improvements are introduced.

- Level 5: Optimized: the organization is focused on a continuous improvement and optimization of the process by implementing innovations. It is regularly checked and updated.

4.3.2. CSR Formal Maturity Measure

4.3.3. CSR Developmental Maturity Measure

4.3.4. Incidental, Tactical and Strategic CSR

5. Results and Interpretation

- Which level of CSR maturity—incidental, tactical or strategic—presented by the companies in Poland covered by the study? (Section 5.1)

- What is the distribution of CSR maturity in the studied population and does the CSR maturity depend on a company’s size and industry? (Section 5.2)

- What is the level of CSR process maturity, CSR formal maturity and CSR developmental maturity, and what practices do the studied enterprises present? (Section 5.3)

5.1. CSR Maturity Level of Enterprises in Poland: Incidental, Tactical and Strategic CSR

5.2. Factors Influencing CSR Maturity

- Frequency distribution of CSR maturity results

- Correlation of CSR maturity and the company size

- Comparative analysis of CSR maturity average results for specific industries.

5.3. Three Perspectives of CSR Maturity

6. Discussion

- Popularization of the CSR concept in small and medium enterprises, which currently demonstrates the lowest CSR maturity.

- Supporting CSR industry standards. Currently most sectors in Poland do not have widely accepted CSR norms.

- Promoting the best CSR practices of the leaders and the CSR maturity model.

- Holistic CSR education, directed at implementing CSR at all three levels of organizational culture: beliefs, values and artifacts. In the area of beliefs, enterprises should be encouraged to reconsider their role and responsibility to the environment. In the area of values, companies should be educated on how to include CSR philosophy in all their fundamental documents i.e., mission statements, codes of conduct, or CSR and business strategies. With regards to artifacts, the education should focus on how to build mature, stable and predictable CSR processes and routines.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Company Name | Industry | Company Name | Industry | Company Name | Industry | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agora | Media | 32 | Enea | Energy | 63 | Netmedia | Media |

| 2 | Alta | Developers | 33 | Erbud | Building | 64 | NTT System | IT |

| 3 | Ambra | Food | 34 | Getinholding | Banks | 65 | Orange Polska | Telecom |

| 4 | Arcus | IT | 35 | Global City Holdings | Media | 66 | P.A. Nova | Building |

| 5 | Asseco Business Sol | IT | 36 | Globe Trade Centre | Developers | 67 | Pamapol | Food |

| 6 | Asseco Poland | IT | 37 | Graal | Food | 68 | Pepees | Food |

| 7 | Asseco South Eastern | IT | 38 | Grupa Azoty | Chemistry | 69 | PGE | Energy |

| 8 | Astarta Holding | Food | 39 | Handlowy | Banks | 70 | PKOBP | Banks |

| 9 | ATM Grupa | Media | 40 | Herkules | Building | 71 | PolEnergy | Energy |

| 10 | ATM | IT | 41 | Hyperion | Telecom | 72 | Polnord | Developers |

| 11 | Bank Millennium | Banks | 42 | Indykpol | Food | 73 | Polskie Gornictwo | Energy |

| 12 | Bank Pekao | Banks | 43 | ING BSK | Banks | 74 | Power Media | IT |

| 13 | BBI Development | Developers | 44 | Instal Krakow | Building | 75 | Prochem | Chemistry |

| 14 | Betacom | IT | 45 | J.W.Construction | Developers | 76 | Projprzem | Chemistry |

| 15 | Bipromet | Building | 46 | K2 Internet | Media | 77 | Qumak Sa | IT |

| 16 | BOŚ | Banks | 47 | Kernel Holding | Food | 78 | Resbud S.A. | Building |

| 17 | BPH | Banks | 48 | Kogeneracja | Energy | 79 | Ronson Europe | Developers |

| 18 | Budimex | Building | 49 | Kruszwica | Food | 80 | Seko | Food |

| 19 | CD Projekt | IT | 50 | LC Corp. | Developers | 81 | Simple | IT |

| 20 | CI Games | IT | 51 | LSI Software | IT | 82 | Sygnity | IT |

| 21 | Ciech | Chemistry | 52 | Macrologic | IT | 83 | Synthos | Chemistry |

| 22 | Colian Holding | Food | 53 | Makarony Polskie | Food | 84 | Talex | IT |

| 23 | Comarch | IT | 54 | Mbank | Banks | 85 | Trakcja PRKII | Building |

| 24 | Comp Safe Support | IT | 55 | Midas | Telecom | 86 | Triton Development | Developers |

| 25 | Cyfrowy Polsat | Media | 56 | Mirbud | Building | 87 | TVN | Media |

| 26 | Dom Development | Developers | 57 | Mni | Telecom | 88 | Ulma Construccion | Building |

| 27 | Echo Investment | Developers | 58 | Mostostal Plock | Building | 89 | Unibep | Building |

| 28 | Elektrobudowa | Developers | 59 | Mostostal Warszawa | Building | 90 | Wasko | IT |

| 29 | Elektrotim | Building | 60 | Mostostal Zabrze | Building | 91 | Wawel | Food |

| 30 | Elkop | Building | 61 | Muza | Media | 92 | WBK | Banks |

| 31 | Elzab | IT | 62 | Netia | Telecom | 93 | Zaklady Miesne Kania | Food |

References

- Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu: Fakty a Opinie. CSR Oczami Dużych i Średnich firm w Polsce; Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu, KPMG: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; Available online: http://odpowiedzialnybiznes.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Raport-Spo%C5%82eczna-odpowiedzialno%C5%9B%C4%87-biznesu-fakty-a-opinie-KPMG-FOB-20141.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Matuszak, Ł.; Różańska, E. CSR Disclosure in Polish-Listed Companies in the Light of Directive 2014/95/EU Requirements: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch, J.; Krasodomska, J. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Empirical Study of Polish Listed Companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, H.; Kulczycka, J.; Hausner, J.; Koński, M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Communication about social and environmental disclosure by large and small copper mining companies. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.; Mućko, P. CSR Reporting Practices of Polish Energy and Mining Companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J. Environmental reporting policy of the mining industry leaders in Poland. Resour. Policy 2017, 53, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijalkowska, J.; Macuda, M. CSR Reporting Practices in Poland. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland. Strategies, Opportunities and Challenges; Długopolska-Mikonowicz, A., Przytuła, S., Stehr, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 195–213. ISBN 978-3-030-00439-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rojek-Nowosielska, M. Społeczne Odpowiedzialność Przedsiębiorstw. Model–Diagnoza–Ocena; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2017; ISBN 978-83-7695-655-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wołczek, P. Development of the CSR Concept in Poland–Progress or Stagnation? Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2015, 387, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. From CSR1 to CSR2: The Maturing of Business and Society Thought; Working Paper 279; Graduate School of Business, University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, W.C. Toward CSR3: Why ethical analysis is indispensable and avoidable in ethical affairs. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1986, 28, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. Moving to CSR4. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1998, 37, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horizons 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Competitive Advantage of Corporate Philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zadek, S. The Path to Corporate Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Mirvis, P.; Googins, B. Stages of Corporate Citizenship. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M.; Felps, W.; Bigley, G. Ethical theory and stakeholder-related decisions: The role of stakeholder culture. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. The Future of CSR: Towards Transformative CSR or CSR 2.0; Kaleidoscope Futures Paper Series; Kaleidoscope Futures: Cambridge, UK, 2012; 17p. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W. CSR 2.0.–Transforming Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility; Springer: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-40874-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martinuzzi, A.; Krumay, B. The Good, the Bad, and the Successful–How Corporate Social Responsibility Leads to Competitive Advantage and Organizational Transformation. J. Chang Manag. 2013, 13, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Crabb, A. Maturity of Strategic Management in Organizations. Oeconomia Copernicana 2016, 7, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persse, J.R. Implementing the Capability Maturity Model; Wiley Computer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paulk, M.C.; Curtis, B.; Chrissis, M.B.; Weber, C.V. Capability Maturity Model for Software, Version 1.1; Technical Report; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, B.; Hefley, B.; Miller, S. People Capability Maturity Model (P-CMM) Version 2.0, 2nd ed.; Technical Report; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Coming to a New Awareness of Organizational Culture. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1984, 12, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic, B. Social Costs of the Transition to Capitalism: Poland, 1990–91; Policy Research Working Paper; Series 1165; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gomułka, S. Poland’s economic and social transformation 1989–2014 and contemporary challenges. Cent. Bank Rev. 2016, 16, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategia Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Polski do 2025. Available online: http://www.access.zgwrp.org.pl/materialy/dokumenty/StrategiaZrownowazonegoRozwojuPolski/wprowadzenie.html (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- EU Green Paper: Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- United Nations Development Programme. Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland. Baseline Study. 2007. Available online: https://ngoteka.pl/bitstream/handle/item/85/spoleczna_odpowiedzialnosc_biznesu.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Grabara, J.; Dura, C.; Driga, I. Corporate social responsibility awareness in Romania and Poland: A comparative analysis. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszewska, E.; Wakuluk, I. Napływ bezpośrednich inwestycji zagranicznych do Polski–szanse rozwoju, scenariusze naprawcze. Zarządzanie i Finanse 2012, 1, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Dyczkowska, J.; Krasodomska, J.; Michalak, J. CSR in Poland: Institutional context, legal framework and voluntary initiatives. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 15, 206–254. [Google Scholar]

- Realizacja Celów Zrównoważonego Rozwoju w Polsce-Raport 2018. Raport Przyjęty przez Radę Ministrów 05.06.2018. Available online: https://www.mpit.gov.pl/media/54729/Raport_VNR_wer_do_uzgodnien_20180330.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Strategia na rzecz Odpowiedzialnego Rozwoju. Accepted by the Council of Ministers on 14.02.2017. Available online: https://www.miir.gov.pl/media/48672/SOR.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Ustawa z Dnia 15 Grudnia 2016 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Rachunkowo’sci [Amended Act to Polish Accounting Act from 15 of December 2016], Dz. U. 2017. Poz. 61. Available online: http://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/du/ 2017/61/D2017000006101.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- European Union Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. 2014. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2014:330:FULL&from=EN (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Sroka, R. Raportowanie Niefinansowe: Wymagania Ustawy o Rachunkowości a Praktyka Rynkowa. Wyniki Analizy ESG Spółek w Polsce 2017; SEG, GES, E&Y: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; ISBN 978-83-946600-4-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability Disclosure Database. Available online: http://database.globalreporting.org (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Biznesu w Polskich Realiach. Teoria a Praktyka. Raport Monitoring Społecznej Odpowiedzialności Największych Polskich Firm; Fundacja CentrumCSR.pl: Warszawa, Poland, 2015.

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Rivers, C. Antecedents of CSR practices in MNCs’ subsidiaries: A stakeholder and institutional perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.; Williams, C.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multi-Level Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Dashdeleg, A.; Lin Chih, H. National Culture and Firm’s CSR Engagement: A Cross-Nation Study. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 5, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, S.S.; Ferreti, L.B.; Parker, L.D. The impact of corporate characteristics on responsibility disclosure: A typology and frequency-based analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 1987, 12, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Gordon, B. A study of the environmental disclosure practices of Australian corporations. Account. Bus. Res. 1996, 26, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder-Webb, L.; Cohen, J.R.; Nath, L.; Wood, D. The supply of corporate social responsibility disclosures among U.S. firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 84, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, G.K.; Roberts, C.B.; Gray, A.J. Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by US, UK and continental European multinational corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1995, 26, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2011, 5, 233–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and Organizations. Int. Studies Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Account. Org. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siregar, S.V.; Bachtiar, Y. Corporate social reporting: Empirical evidence from Indonesia Stock Exchange. Int. J. Islamic Middle Eastern Financ. Manag. 2010, 3, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Crabb, A. Sustainable Strategy—A Research Report on Sustainability Practices in Polish Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Business Information Management Association Conference IBIMA, Seville, Spain, 15–16 November 2018; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; pp. 6087–6100. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, L.C.J.; Taylor, M.E. An empirical analysis of triple bottom-line reporting and its determinants: Evidence from the United States and Japan. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2007, 18, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Firm Size, Organizational Visibility and Corporate Philanthropy: An Empirical Analysis. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do Consumers Expect Companies to be Socially Responsible? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Affairs 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of the Firm Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Roberts, R.W.; Patten, D.M. The language of US corporate environmental disclosure. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Gordon, I.M. An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies: Determinants, costs and benefits. Account. Audit. Accoun. 2001, 14, 587–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.L.; Zimmermann, J.L. Positive accounting theory: A ten year perspective. Account. Rev. 1990, 65, 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greening, D.W.; Gray, B. Testing a model of organizational response to social and political issues. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 467–498. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, A.; Kolk, A. Extrinsic and intrinsic drivers of corporate social performance: Evidence from foreign and domestic firms in Mexico. J. Manag. Studies 2010, 47, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, G.R.; Treviño, L.K.; Cochran, P.L. Integrated and decoupled corporate social performance: Management commitments, external pressures, and corporate ethics practices. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. From issues to actions: The importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.M.; Steensma, H.K.; Harrison, D.A.; Cochran, P.L. Symbolic or substantive document? The influence of ethics codes on financial executives’ decisions. Strategy Manag. J. 2005, 26, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Crabb, A. Evolutionary models of CSR—Between the paradigms of moral and economic value creation. In Proceedings of the EURAM Annual Conference: Making Knowledge Work, Glasgow, UK, 21–24 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, C.W. Human Nature Prepares for a Momentous Leap. Futurist 1974, 8, 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, K. A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality; Shambhala Publications, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-57062-724-8. [Google Scholar]

- Halme, M.; Laurila, J. Philanthropy, Integration or Innovation? Exploring the Financial and Societal Outcomes of Different Types of Corporate Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkston, T.S.; Carroll, A.B. A retrospective examination of CSR orientations: Have they changed? J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Organizational Stages and Cultural Phases: A critical Review and a Consolidative Model of Corporate Social Responsibility Development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Woot, P. Should Prometheus Be Bound; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-230-57812-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frooman, J. Socially Irresponsible and Illegal Behavior and Shareholder Wealth. A Meta-Analysis of Event Studies. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.J.; Mahon, J.F. The Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance Debate. Twenty-Five Years of Incomparable Research. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, S.; Popkin, S.J. Integrating ethics into the strategic management process: Doing well by doing good. Manag. Decis. 1998, 36, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Performance–Financial Performance Link. Strategy Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D. Shareholder Value, Stakeholder Management, and Social Issues: What’s the Bottom Line? Strategy Manag. J. 2001, 22, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribo, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strategy Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0875896397. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, P. Interpreting text: An alternative to some current forms of textual analysis in qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Health 1995, 1, 236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki, N.L.; Wellman, N.S. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoud, N.S.; Kavanagh, M.; Slaughter, G. Factors influencing levels of corporate social responsibility disclosure by Libyan firms: A mixed study. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2012, 4, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.H.W.A.; Zain, M.M.; Al-Haj, N.H.Y.Y. CSR disclosures and its determinants: Evidence from Malaysian government link companies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussainey, K.; Elsayed, M.; Abdel Razik, M.A. Factors affecting corporate social responsibility disclosure in Egypt. Corp. Ownersh. Control J. 2011, 8, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, A. The corporate social responsibility disclosure: A study of listed companies in Bangladesh. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 2, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tagesson, T.; Blank, V.; Broberg, P.; Collin, S.O. What explains the extent and content of social and environmental disclosures on corporate web sites: A study of social and environmental reporting in Swedish listed corporations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, W.J.; Levine-Donnerstein, D. Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1999, 27, 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; ISBN 13 978-0134202136. [Google Scholar]

- Philipson, G. A Green ICT Framework: Understanding and Measuring Green ICT; Connection Research Services Pty Ltd.: St Leonards, Australia, 2010; ABN 47 092 657 513. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, D.; Cowan, C. Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership and Change; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 155786-940-5. [Google Scholar]

- Witek-Crabb, A. CSR Versus Business Financial Sustainability of Polish Enterprises. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland. Strategies, Opportunities and Challenges; Długopolska-Mikonowicz, A., Przytuła, S., Stehr, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 43–58. ISBN 978-3-030-00439-2. [Google Scholar]

| Industry | Number of Companies |

|---|---|

| Banking | 10 |

| Chemistry | 5 |

| Construction | 16 |

| Developers | 11 |

| Energy | 5 |

| Food | 13 |

| IT | 20 |

| Media | 8 |

| Telecommunication | 5 |

| TOTAL | 93 |

| Company Size | Number of Companies | |

|---|---|---|

| Small | 1–50 employees | 8 |

| Medium | 51–250 employees | 21 |

| Large (>250 employees) | Medium big: 251–500 employees | 14 |

| Big: 501–5000 employees | 34 | |

| Very big: >5000 employees | 16 | |

| TOTAL | 93 |

| Score (Points) | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial | Some or no CSR awareness. Considered but not implemented. |

| 2 | Repeatable | Some ad hoc CSR, fragmented implementation, but no strategy. |

| 3 | Defined | Formal CSR programs have been defined, but implementation is inconsistent. |

| 4 | Managed | Methodological implementation of programs with adequate measurement and management. |

| 5 | Optimized | All CSR activities are monitored and managed for optimal performance. Best practice. |

| Document | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mission statement | 0 | None/not available |

| 0.5 | Commitment to traditional stakeholders like customers and/or shareholders | |

| 1 | Commitment to a wide group of stakeholders | |

| Code of conduct | 0 | None |

| 0.5 | Brief values declaration | |

| 1 | Extended code of conduct | |

| Corporate governance statement 1 | 0 | No CG statement |

| 0.25 | Over 20 exclusions in CG statement | |

| 0.5 | 10–20 exclusions in CG statement | |

| 1 | Less than 10 exclusions in CG statement | |

| CSR report | 0 | None/not available |

| 0.5 | Brief account | |

| 1 | Extended report following guidelines i.e., GRI | |

| CSR strategy | 0 | None/not available |

| 0.5 | Brief plan or declaration | |

| 1 | Separate extended document | |

| CSR as part of the corporate strategy | 0 | None |

| 0.5 | CSR as one of the elements of corporate strategy | |

| 1 | CSR as an overriding perspective in corporate strategy | |

| Management systems and awards | 0 | None |

| 0.5 | Quality oriented management systems/awards (i.e., ISO 9000) | |

| 1 | CSR oriented management systems/awards (i.e., ISO 14000) | |

| CSR acknowledgment | 0 | None |

| 0.5 | Participation in CSR organizations or in RESPECT Index 2 | |

| 1 | Participation in CSR organizations and in RESPECT Index |

| Score | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-responsibility (red) | Egoism and loyalty of a business to itself. Lack of CSR activities unless they are forced externally (strikes, external pressure, law) |

| 2 | Compliance (blue) | Business undertakes actions requiring social responsibility because of the sense of obligation and within the framework required by law and explicit social expectations. Ad hoc charity and sponsorship involvement. |

| 3 | Profit (orange) | Business uses CSR activities to earn profit, thus strategically integrating environmental, ethical, and social aspects of its operations. Triple bottom line and CSR business case. |

| 4 | Care (green) | CSR initiatives go beyond what is required by law and what is the business case, and results from the care for the planet and for people. The motivation is human potential and sense of responsibility. |

| 5 | Synergy (yellow) | CSR activities are characterized by looking for win-win solutions and for the harmony between what is environmental and social. Motivation comes from the sense that sustainability is important. |

| 6 | Holism (teal) | Social responsibility permeates every aspect of the organization and the business is oriented towards improving the quality of life of all beings. Motivation for CSR comes from the awareness of a correlation between all events and beings. |

| CSR Maturity Level | Score | CSR Process Maturity | CSR Formal Maturity | CSR Developmental Maturity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INCIDENTAL CSR | 0–0.32 |

|

|

|

| TACTICAL CSR | 0.33–0.65 |

|

|

|

| STRATEGIC CSR | 0.66–1 |

|

|

|

| CSR Maturity Level | CSR Maturity Score | No. of Companies | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidental CSR | 0–0.32 | 44 | 47 |

| Tactical CSR | 0.33–0.65 | 29 | 31 |

| Strategic CSR | 0.66–1.0 | 20 | 22 |

| Total | 93 | 100 |

| CSR Maturity Score | |

|---|---|

| Company size (no. of employees) | 0.651 * |

| CSR Maturity | Company Size (No. of Employees) | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (1–50) | Medium (51–250) | Large (>250) | ||

| Incidental CSR | 7 | 17 | 20 | 44 |

| Tactical CSR | 1 | 3 | 25 | 29 |

| Strategic CSR | 0 | 1 | 19 | 20 |

| Total | 8 | 21 | 64 | 93 |

| CSR Maturity Level | Industry | Industry Average CSR Maturity Score | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidental CSR | Telecommunication | 0.26 | 120% |

| (0–0.32) | IT | 0.28 | 47% |

| Tactical CSR (0.33–0.65) | Developers | 0.33 | 53% |

| Media | 0.33 | 70% | |

| Food | 0.40 | 51% | |

| Construction | 0.44 | 55% | |

| Chemistry | 0.48 | 56% | |

| Banking | 0.64 | 42% | |

| Strategic CSR (0.66–1.0) | Energy | 0.70 | 12% |

| CSR Process Maturity | Number of Companies | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | Total | ||

| Initial | 7 | 16 | 21 | 44 | 47 |

| Repeatable | 1 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 16 |

| Defined | 0 | 1 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Managed | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Optimized | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Total | 8 | 21 | 64 | 93 | 100 |

| Document | Level of Practice | Number of Companies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | Total | % | ||

| Corporate governance statement | No CG statement | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 | 12 |

| Over 20 exclusions in CG statement | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 10 | |

| 10–20 exclusions in CG statement | 1 | 10 | 18 | 29 | 31 | |

| Less than 10 exclusions in CG statement | 5 | 4 | 35 | 44 | 47 | |

| Total | 93 | 100 | ||||

| Mission statement | None/not available | 7 | 11 | 24 | 42 | 45 |

| Commitment to traditional stakeholders like customers and/or shareholders | 1 | 8 | 23 | 32 | 34 | |

| Commitment to a wide group of stakeholders | 0 | 2 | 17 | 19 | 21 | |

| Total | 93 | 100 | ||||

| Code of conduct | None | 8 | 12 | 24 | 44 | 47 |

| Brief values declaration | 0 | 6 | 13 | 19 | 21 | |

| Extended code of conduct | 0 | 3 | 27 | 30 | 32 | |

| Total | 93 | 100 | ||||

| CSR/Sustainability report | None/not available | 7 | 17 | 27 | 51 | 55 |

| Brief account | 1 | 3 | 23 | 27 | 29 | |

| Extended report following guidelines i.e., GRI | 0 | 1 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| Total | 93 | 100 | ||||

| CSR/Sustainability strategy | None/not available | 7 | 16 | 24 | 47 | 50 |

| Brief plan or declaration | 1 | 5 | 28 | 34 | 37 | |

| Separate extended document | 0 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 13 | |

| Total | 93 | 100 | ||||

| CSR Process Maturity | Number of Companies | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | Total | |||

| Pre-responsibility | Red | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| Compliance | Blue | 6 | 17 | 26 | 49 | 53 |

| Profit | Orange | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

| Care | Green | 1 | 2 | 9 | 12 | 13 |

| Synergy | Yellow | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

| Holism | Teal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 8 | 21 | 64 | 93 | 100 | |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Witek-Crabb, A. CSR Maturity in Polish Listed Companies: A Qualitative Diagnosis Based on a Progression Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061736

Witek-Crabb A. CSR Maturity in Polish Listed Companies: A Qualitative Diagnosis Based on a Progression Model. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061736

Chicago/Turabian StyleWitek-Crabb, Anna. 2019. "CSR Maturity in Polish Listed Companies: A Qualitative Diagnosis Based on a Progression Model" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061736