1. Introduction

From different perspectives institutions have been considered central elements in explaining the evolution of regional economies and a wider group of researchers have increasingly generated empirical and analytical evidence of their role in regional development processes [

1,

2]. In this context, Institutional Thickness, theorized by Amin and Thrift [

3], is considered a key condition to promote economic development as well as mobilize actors, organizations, and resources.

Over the last four decades, commitment to tourism as a development strategy for developing economies has increased [

4]. More precisely, in Latin America, tourism is considered a useful development tool, especially at the regional level [

5]. Tourism is an activity in which planners, researchers, and policy makers strive to find successful development models. Sometimes, the success of these models is related to the role of public institutions and private organizations [

6] but existing theory, evidence, and research on the role played by institutions in the evolution of tourist destinations and their regional importance as a development tool has been little explored. However, some contributions have recently started to discuss, although not explicitly, the role of institutions in regional tourism development from the evolutionary economic geography approach [

7].

Admitting that other factors also influence regional tourism development, this study aimed to analyze the impact of institutions in regional tourism development using the institutional thickness concept, and therefore to study how the coordination and interaction of public and private institutional structures affect the intensity and nature of regional tourism. Taking into account these preliminary considerations, this research examined the perception of 28 institutional representatives regarding the role of institutions in tourist development in the region of Antioquia, Colombia.

With this goal, the organization of the paper is structured into six fundamental sections. In

Section 2, the theoretical foundation of the concept of institutional thickness and its relationship to regional tourism development is discussed.

Section 3 presents the regional context of this study.

Section 4 explains the methodological process, while

Section 5 examines the results.

Section 6 describes the usefulness of applying the institutional thickness approach to better understand the dynamics of regional tourism development. Finally,

Section 7 highlights some key features derived from the research.

2. Institutional Thickness and Regional Tourism Development

At the end of the 20th century, a new vision emerged in the economy highlighting the role of institutions in economic performance: the new institutional economy (NIE) [

8]. The NIE is a stream of thought initially developed in the mid-1970s but still perceived today as relatively young [

9]. According to Ménard [

10], the analysis of institutions, their most important characteristics, and how they interact with different organizational solutions is still in its initial stages. Economists such as Coase [

11], who regarded transaction costs in companies and society; North [

12], who dealt with institutions, institutional change, and beliefs; Williamson [

13], who discussed hierarchies, markets, and governance of organizations; and Ostrom [

14], who focused on the governing of common resources, social capital, and complex economic systems, have played an important role in its emergence [

15]. The purpose of the NIE is to explain the role of institutions in social life using an economic language, but integrating concepts from disciplines such as law, political science, geography, sociology, history, and anthropology. It can be summarized by two central ideas: institutions matter, and they are susceptible to analysis [

13].

Despite the existence of nuances and discrepancies [

13], the most common definition of an institution was developed by North [

12], who defined it as the restrictions that arise from human inventiveness to limit political, economic, and social interactions. Institutions are, in short and formally, the result of rules created by humans that shape their interaction, and, according to this author, institutional changes delineate the way society evolves over time and are at the same time key to understanding historical change. From another angle, according to Bathelt and Glucker [

16], institutions can be defined as correlated and relatively stable social interactions between economic agents that develop upon rules and regulations in rather contingent ways. In any case, it is acknowledged that institutions are fundamental in explaining the economic performance of specific societies or social groups [

17] and answering why some institutional frameworks are efficient in promoting economic development while others are not [

18].

There are three ways to classify institutions [

19], according to the degree of formality, the scope of action, and the levels of hierarchy. The degree of formality has to do with the rules that regulate the institutions. Formal rules can be classified into constitutions, laws, property rights, common laws, contracts, and statutes, while informal rules are the norms of behavior sanctioned by society (traditions and beliefs). Depending on their scope of action, institutions can be economic, political, legal, or social. Finally, regarding the different levels of hierarchy, Williamson [

13] proposed the differentiation that appears in

Figure 1. It should be said that, given the objectives outlined in the Introduction, we raise issues related to the level of hierarchy 3; that is, we take into account the relationships between public and private institutional structures.

2.1. Institutions, Regional Development and Governance

In recent years, a considerable amount of work has been developed that analyzes the impact of institutions at a regional level [

20]. Existing research shows how the evolution of the institutional structure of a region explains growth processes and a great variety of results over time, both between countries and between regions within a country. The importance of institutions for regional development has become particularly evident; for instance, when reforms promoted by multilateral organizations fail, it is either because they are focused exclusively on specific economic policies and forget the institutions, or because they look for a harmonization of the role and form of institutions according to similar patterns, regardless of the circumstances of time and place [

21].

Even though the relationships between institutions and the regional development of a territory have been analyzed from different perspectives, the main empirical efforts have focused mainly on analyzing formal institutions and their impact on economic performance over time [

22] by studying the differences in growth rates, government performance, and structures of each country [

23]. For example, Rodrik, Subramanian, and Trebbi [

24] found that “the estimated direct effect of institutions on income is positive and large”. Alternatively, according to Jütting [

19], institutions can have indirect impacts derived from increased investment, better management of ethnic diversity and conflicts, better policies, and increased social capital of a community. Complementarily, more recent significant work has been carried out observing links between institutional structure and regional development, regional innovation systems, regional competitiveness, leadership at a local level, relationships with the government, and intersections with human capital [

25]. Overall, the existing research on institutions has made two important breakthroughs in recent years. First, studies have shown quite clearly that institutions matter to economic growth and development. Second, it has begun to lay the theoretical groundwork for explaining why institutions matter and how these institutions are shaped [

26]. Nevertheless, studies have also shown that, in certain circumstances, the institutional structure can be an obstacle to development [

19]. In this way, there is evidence that the impact depends not only on the quality of the institutional environment, but also on factors such as the local environment, the interests and behavior of the actors involved, the level of education, the quality of infrastructures, local resources, or the level of urbanization [

25].

In their seminal work

Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of long-run Growth, Acemoglu et al., [

27] argued that there is evidence that whether or not a society grows depends on how its economy is organized on its economic institutions. They also emphasized the idea that institutions are based on politics and on the structure and the nature of political power and this relates to the notion of social-political governance [

28]. Therefore, regional development is highly influenced by patterns of governance in which institution building and institution change have prominent roles [

29] and policymakers are looking to regional governance as a framework for improving local and regional competitiveness [

30]. In this framework, the term governance implies systems of governing and the ways in which societies are governed [

31] and how these systems bring legitimacy to political processes [

32].

In the scope of regional tourism development, governance is clearly a significant concept related to the adaptation of destinations to change [

33]. It also draws attention to how governmental and non-governmental organizations often work together [

31] developing rules and mechanisms for a policy, as well as business strategies and involving all the institutions and individuals [

34,

35]. In this framework, institutions give expression, shape and influence to the context for successful or unsuccessful regional development [

36] mixing both identity and economy [

37].

2.2. Institutional Thickness as a Driver for Regional Development

Among the broad and diverse set of disciplinary perspectives created from the study of institutions based on the contributions made by North [

12], the notion of institutional thickness emerges as a leading concept within economic geography and regional development studies [

3]. institutional thickness refers to the density of institutions and organizations that act in a territory to promote development actions [

38]. The concept was introduced in a collection of essays under the title

Globalization, Institutions, and Regional Development in Europe published in 1994 by Amin and Thrift [

3]. According to their observations, institutional thickness explains the superior positioning of some regions with respect to others. Recent research has also highlighted that the performance of institutions explains the success of different territories [

39]. Thus far, researchers such as Rodríguez-Pose [

39] have emphasized the importance of developing an approach that focuses on analyzing institutional effectiveness. Some researchers dedicated to the analysis of institutions have linked regional development to the density or thickness of institutions [

3,

39]. The basic idea of this approach is that the greater is the institutional thickness of a region, the greater is its capacity for growth.

Institutional thickness implies a series of organizational, sociocultural, and economic criteria. It covers different types of institutions, including financial entities, local chambers of commerce, development agencies, local authorities, innovation centers, schools, government agencies, employers, and administrative bodies. It is a complex concept that refers not only to the existence of organizations linked to territorial economic activity, but also fundamentally to the interaction between companies, intermediate organizations, and local public powers [

40]. According to Amin and Thrift [

3], institutions generate greater legitimacy by nurturing trust relationships, stimulating entrepreneurial capacity, and consolidating the empowerment of economic activity in the local environment with institutional thickness.

Institutional thickness as theorized by Amin and Thrift [

3] can therefore be characterized as follows: strong institutional presence, high levels of interaction between organizations, domain structures and/or coalition patterns, identification with a common purpose, and existence of shared norms and values. Institutional presence refers to the existence of different organizations, such as development agencies, government agencies, associations and business service organizations, trade unions, and research institutes, that represent local actors and collectives. Levels of interaction refer to the importance of formal and informal knowledge exchange and the relevance of cooperation among organizations. Domain structures and/or coalition patterns refer to the leadership of the coordination processes that take place, result in a collective representation of what are usually individual interests and balance the differences between institutions that are capable of exerting a dominant influence and those that are not. Finally, mutual awareness and common purpose imply that there is a common agenda. This common agenda for development may be formally defined or simply a collaborative set of priorities. In this context, each institutional actor is a political, economic, social, and cultural agent that promotes situations aimed at capitalizing on local potentialities and assuming an active role in accompanying the development process. The weight of each actor can change during the process of organization and participation.

Since Amin and Thrift [

3] introduced the concept of institutional thickness, various approaches have been developed offering remarkable information to understand the factors that drive regional economic development. Probably one of the most significant contribution was developed by Wood and Valler [

41], who edited a collection that included various articles on theoretical and empirical approaches to developing different aspects of the concept. Moreover, recent academic works move toward frameworks that facilitate the analytical operationalization of the concept. In this respect, following Amin and Thrift [

3], ten years later, Coulson and Ferrario [

42] applied an empirical approach to develop some indicators related to the original concept: institutional presence, degree of interaction, common enterprise, and structure of domination and coalition. They also highlighted that the institutional thickness concept is not without problems. For instance, they discussed issues such as how the term “institution” has different interpretations and is approached in different ways depending on the framework of the discipline (e.g., sociology and institutionalism), to what extent conflating organizations with institutions is an important point to keep in mind and which are limitations derived from the perception that may not be possible to create or replicate an institutional structure.

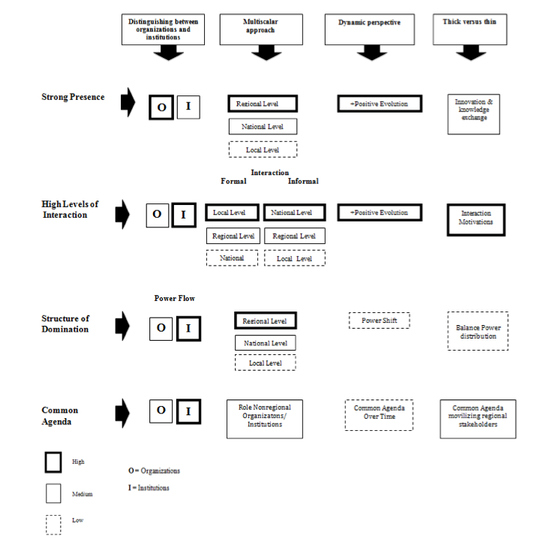

In this same vein, such as the one developed by Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43], have made contributions that could lead to the development of a more complete empirical application of institutional thickness, including some elements that have a prominent place in the research agenda of institutional economic geography [

39,

44], relational economic geography [

33,

34], and geographic political economy [

43]. These elements discuss the concept in terms of the idea of considering four fundamental issues: the distinction between organizations and institutions, since each can play a very different role; the consideration of different territorial scales, including relationships between local and nonlocal agents; an evolutionary perspective based on changes in power over time; and the relationship of institutional/organizational density with innovation (thick vs. thin) (see

Figure 2).

Therefore, this last approach integrates a much broader evaluative context, identifies the role of relevant institutions and power relations between different organizations, deals with the balanced power distribution, and discusses the role of organizational and institutional structures that support knowledge exchange and innovation, among others. Such progress represents a change in the study of institutional thickness in a territory, and therefore in the methodology to develop indicators to gain deeper knowledge in this field and stronger empirical evidence.

Finally, it should be noted that, at least until now, most of the existing analyses around institutional thickness have been applied in the context of industrial areas and developed countries, hence the interest in considering its role in the regional development of a Latin American area in relation to its evolution as a tourist destination.

Many developed and developing countries consider tourism as important for economic progress, but the relationship between tourism and regional economic development [

45], as far as it depends on the development of general policies and regulatory and institutional frameworks, is still unclear. There is a need to investigate how the density of public and private institutional structures and their coordination and interaction may affect the intensity and nature of regional tourism development. There is also a need to provide knowledge about the role of institutions as entities that monitor, promote, harmonize, and collect the interests, expectations, and objectives of actors in the industry and why institutional forms can produce distinctive economic results in each place. In this sense, recent studies reflect how regional tourism development depends, to a great extent, on human agency. Velasco [

46], for instance, discussed factors that imply the collaboration of public and private sector and have enormous potential, and Brouder [

47] debated how research can move from the “what” to the “how” and “why” of regional tourism development.

Thus, the analysis carried out in this study was intended to introduce the observation of the evolution of destinations from the perspective of regional tourism development, adopting the concept of institutional thickness, which has been applied in other areas of knowledge and different territorial contexts. It shows how this kind of approach can enhance its application in the analysis of regional tourism development. For this purpose, the study developed a case study of one Latin American region, Antioquia, Colombia, between 2000 and 2015. The analysis provided evidence on the usefulness of this concept in the context of regional tourism destinations.

3. Antioquia: Introduction to the Regional Context

Antioquia is located in the central northwestern part of Colombia. It is Colombia’s most populated region (6,690,980 inhabitants in 2018) and the largest economy after Bogota’s capital district. According to data from the Colombian Statistical Office [

48], Antioquia contributes USD 46,658 million to the Colombian State, representing 15% of its total GDP. Commerce and manufacturing are the most thriving sectors in Antioquia, representing 15.9% and 15.7% of its total GDP, respectively.

During 2000–2015, Antioquia implemented a key strategy for tourism development based on empowering social actors and creating and reinforcing local and regional public and private institutions [

49]. In the framework of this process, Antioquia and Medellín, the capital city, have been transformed, particularly Medellín [

50]. Therefore, in recent years, the city has received significant international recognition, such as City of the Year (2013), the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize (2016), and the best tourist destination in South America according to TripAdvisor—Traveller’s Choice (2018); it was also nominated for the World Travel Awards in 2018.

This evolution has occurred in the context of the relevant growth of tourism not only in Antioquia, but also in Colombia (see

Figure 3) during the last 10 years [

48]. Specifically, while the growth rate of tourist arrivals worldwide was 7% in 2017, in Colombia it was 28% over the last 10 years.

Analyzing regional tourism development in Colombia as well as economic performance and dynamics implies considering the various socio-political and economic processes that have taken place in the country [

51]. These dynamics of growth are within the context of a chain of events and decisions that have supported tourism development in addition to other very important factors, such as improvements in the country’s security conditions, the positive perception of Colombia abroad, the strengthening of infrastructures, and increased foreign investments, among others.

In this line,

Figure 4 summarizes the main events that have marked the tourist development of the country since 2000 and the strategic decisions that help to make Colombia a tourist destination. In addition to the many implemented decisions concerning security, three key events can be highlighted as the basis for the development of the tourism sector: the creation of the Vice Ministry of Tourism (2006); tourism sectoral plan

Colombia world-class tourist destination (2008–2010) within which the successful international communication campaign was launched, name of the campaign:

Colombia the only risk is wanting to stay; and finally one of the most recent historical milestones, the signing of the Peace Agreement between the government and the FARC (2016).

More specifically, in Antioquia, the starting point was in 1999, when the Council of Competitiveness of Antioquia started long-term, interinstitutional, constructive work to design a Vision Antioquia for the 21st Century. This was the result of an extensive process of agreement among all sectors, defining opportunities for the region in the globalized world and creating an unwavering and united force as a region. As a result, after 8,756 hours of dialogue, an unprecedented agreement for the future was established in the recent history of Colombia with the ambitious vision to convert Antioquia: “In the year 2020 [in] the best corner of America, fair, peaceful, educated, booming and in harmony with nature” [

52]. In this vision, tourism was presented as a key element of economic development, from the business side but also in terms of the city and regional governance strategy, which implied the creation and reinforcement of specific institutions. This vision made progress with the creation and consolidation of key institutions to support regional tourism development (

Figure 5).

The vision marked the initial development of an agenda of strategic actions to respond to anticipated challenges in the region. That common agenda was materialized with the PLANEA: Strategic Plan for Antioquia, which has guided the decisions and actions of actors and sectors interested in the region’s development toward the achievement of shared goals [

53].

In 1995, the Medellín Chamber of Commerce contracted the firm Monitor, created by Michael Porter, to conduct studies on the competitiveness of some industrial sectors in Antioquia. As a result of those studies, the creation of clusters was identified as a priority for Antioquia’s competitiveness. In response, the region prioritized the most important economic activities and established the Cluster Community, by which the integration of public and private sectors was achieved to generate agendas focused on economic development. The developed clusters were energy (2007); textiles, design, and fashion (2008); business tourism (2008); construction (2008); medical and odonatological services (2009); and technology, information, and communication (2009). Clustering efforts have achieved satisfactory results in terms of GDP growth, private investment, and new employment. Since then, the focus in the region has been on uniting public and private interests as well as guiding how the new efforts can generate new public policy, confidence, and innovative businesses in the region.

Another important road map for the region and its tourism sector was a process initiated by the Tourism Development Plan of Medellín 2000–2009, which soon became the city’s tourism guidebook. The plan helped to clarify a common vision and strengthened the partnership-based approach to defining and implementing tourism policy.

Figure 5 shows how Antioquia made progress in the creation and consolidation of key institutions to support regional development in tourism during the study period. The institutional integration between the public and private sectors was also formalized with the creation of the Business Tourism Cluster, and Medellín Convention and Visitors Bureau. In addition, a national context of opening new airlines, hotels, and theme parks and the creation of the Vice Ministry of Tourism in 2006 was transcendent.

Finally, it should be noted that economic growth and job creation in many regions of the country generated a significant increase in disposable income for families and allowed domestic tourism development initiatives. At the regional level, tourism was recognized as a key element of local economies. This recognition was evident in the development plans at both the national and regional level [

54].

In this transformative context, the hypothesis that the role of institutions in the dynamics of tourism regional development was fundamental can be stated, and this is therefore the key point of analysis.

4. Research Design and Methodology

Recent discussions on differences in development between different regions highlight the importance of institutions [

27,

39,

51]. The concept of institutional thickness can therefore be conceived as a building block for an analytical and replicable approach to the analysis of the role of institutions in regional development [

42]. Institutional thickness refers to the density of institutions and organizations that act in a territory to promote development actions. It is characterized by four main elements: strong institutional presence, high levels of interaction between institutions and organizations, domain structures and/or coalition patterns, identification with a common agenda or mutual awareness.

The role of institutions and their impact on regional tourism development has not yet been analyzed in terms of institutional thickness, much less in a Latin American context. This is an opportunity and a challenge to contribute as much to the literature on tourism as to the investigations in regional science, even though indicators of institutional thickness are quite difficult to estimate [

43].

To develop the analysis of institutional thickness in this study, parameters set out in

Table 1 are defined. They address both the key elements related to institutional thickness already discussed by Amin and Thrift [

3] and those updated and adapted by Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43].

In this framework, to understand the role of institutional thickness in tourism regional development, four research hypotheses were set up and an experimental approach was developed. The hypotheses are the following.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Institutional development has played a significant role in regional tourism development.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Institutional level and types of interactions between institutions shape the extent of regional tourism development.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Regional tourism development depends both on the performance of structures of domination among institutions and on the role played by institutions in collective spaces of representation.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The building of interinstitutional common agendas is key for regional tourism development.

4.1. Data Collection

The process of obtaining data to observe the strength of institutional presence in the region, the levels of interaction among organizations, the existing domain structures and/or coalition patterns, the identification of a common purpose, and the existence of shared norms and values was carried out through a qualitative research procedure. The design and implementation of the data collection procedure were carried out in two phases.

The first phase consisted of structured interviews with the aim of having a preliminary view of the institutional structure of the region and knowing the level of importance that interviewees assigned to institutions regarding tourism development over 15 years (2000–2015) (see

Appendix A). Interviews were conducted between May and June 2016, and selected institutions were approached according to their relevance as tourism-related organizations in the region. Institutions interviewed in this phase included the following: Governorate of Antioquia, Directorate of Tourism Development of Antioquia, Medellín Chamber of Commerce, Vice Presidency of Planning and Development, Undersecretary of Tourism/Mayor’s Office of Medellín, Medellín Convention and Visitors Bureau, Hotel and Tourism Association of Colombia (COTELCO), and National Federation of Merchants (FENALCO). The interview data were analyzed through the interview transcripts, identifying topics highlighted in the answers, elaborating on descriptive summaries and further evaluating the connections of these issues with the conceptual framework.

The second phase consisted of designing a questionnaire to obtain measurements for the defined variables and provide evidence on the impact of the institutions on regional tourism development over 15 years (2000–2015). Selected institutions included tourism and regional development agencies (6); local, regional, and national authorities (5); business service organizations (2); chambers of commerce (4); associations (5); universities (4); and research and innovation centers (2).

To identify the appropriate institutions, the process began with mapping the institutions established in the region that were directly or partially related to tourism development. During this process, up to 34 institutions were identified as having played a significant role in the development of tourism in Antioquia between 2000 and 2015. Of these 34 institutions, 28 took part in the study. The other six institutions did not reply to the survey. However, this does not represent a significant negative impact on the analysis, because we obtained the participation of the most active and relevant stakeholders in the territory. In any case, the following institutions did not participate: Colombian Association of Travel and Tourism Agencies (ANATO), Turibus (tourist bus), Chamber of Commerce of Urabá (only involves a small proportion of the region), Tourist Corporation of Bajo Cauca (only involves a small proportion of the region), Comfenalco (a private nonprofit organization), and Fontur (a public institution at a national level).

It is important to note that, following Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43], we decided to differentiate between institutions and organizations. Differences between the two types were determined by the characteristics of their structure; that is, whether they function through public or private arrangements and resources. Institutions refer to authorities that design and regulate norms, laws, policies, and context conditions. Organizations include firms, universities, support agencies, and associations, among others. According to Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43] (p. 331), “mapping institutions and organizations as separate entities provides a more detailed analysis into the factors underpinning regional development, and more precise identification of the strengths and weaknesses of the specific context under consideration”. In our case, these distinctions were very useful to understand what happens inside the region, not only in terms of density but also regarding coordination, leadership, resources, and operationalization of territorial objectives.

4.2. Questionnaire Design

Questionnaire surveys are a popular data collection method for academic research in a variety of fields. This type of data gathering method was useful in this study to collect, analyze and interpret the different views of institutions and organization involved in Antioquia’s tourism development. Therefore, an online questionnaire was sent to the target agents between July and December 2016 through the online platform SurveyMonkey®. The questionnaire included open, multiple choice, and Likert scale questions. The questions were divided into five thematic sections (see

Appendix B). The first section referred to general information data, which included general information about the institution, territorial scope, information on the estimated budget, and percentage of resources allocated to regional tourism development. The second section was about the role played by the institution in the development of tourism in the region (infrastructure, governance, business fabric, arrival of visitors, and economic and social impact). The third section was about the level of interaction within the network of institutions involved in tourism development, their degree of involvement, cooperation, and exchange of information. The fourth section explored the governance structures resulting from the collective representation of what are usually individual and/or sectoral interests, formal and informal representation spaces that allowed the objectives as a tourist destination to be achieved. Finally, the fifth section collected information related to the development of common agendas and projects that allowed the promotion of tourism development in the region. Additionally, four more questions were asked regarding general opinions on the importance of the institutions for regional tourism development.

Data collected over this period were subsequently analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Data for 28 institutions/organizations were entered in the tool and processed using nominal, ordinal, and interval data.

The following section presents results based on the analysis from interview data and survey responses.

5. Results

According to the idea that institutional thickness should focus on the perceptions of regional economic agents on their institutional environment [

43], this section operationalizes the concept through the research findings with the aim of describing each institutional thickness feature in the regional tourism development of Antioquia.

5.1. Strong Institutional Presence

The first element of institutional thickness refers to the existence of an institutional and organizational fabric represented by different types of structures. In this analysis, this approach explores the number (density) of institutions/organizations involved in regional tourism development, their commitment, and the spatial scale.

Appendix C shows the institutions/organizations involved in the tourism sector of Antioquia that participated in the study. These institutions/organizations are classified according to legal and administrative structure as public, private, or mixed (private–public). The commitment to tourism development can be exclusive or partial, and this feature is provided in accordance with the functions attributed to each institution/organization and the budget allocated for tourism development. Regarding this item, participating institutions/organizations considered that their commitment to tourism development evolved positively. In fact, a large proportion of the institutions and organizations exclusively dedicated to tourism development were created after 2000 (see

Table 2).

Based not only on the number of institutions/organizations in the region, but also on their efficiency and impact on tourism growth, 53% of those interviewed considered the existence of institutions as an explanatory factor in improving the governance of the destination and 52% considered the creation of new institutions between 2000 and 2015 as fundamental to tourism development.

The creation of institutions related to tourism development in the region demonstrates a strong institutional presence. This is evidenced not only in the number of institutions, but also in their ability to play their role properly, apply their knowledge, and allocate the necessary resources for regional tourism development. Having institutions/organizations that are committed to general economic development strengthens and fundamentally supports the competitiveness of the destination.

Such development can be traced in the region in general and in Medellín in particular. Regarding general regional institutions, an important aspect has been the incorporation of the development of the tourism industry into their agendas, which help to explain the tourism’s positive performance in recent years. Otherwise, at the regional level, findings highlight a lack of political continuity, particularly in the case of the government of Antioquia. Finally, results obtained show that a large part of the organizations constituted since 2000 were created with a specific objective related to tourism development and, therefore, with a higher level of specialization.

5.2. High Levels of Interaction

Levels of interaction between institutions are related to the importance of formal and informal knowledge exchange and the relevance of cooperation. In this regard, 57% of the interviewees considered the level of interaction between institutions/organizations as intermediate. In the words of one interviewee: “Sometimes the interaction has been complicated by the difference in visions and objectives, and particularly the interest to play the leading role. Institutions are made up of people, and in certain circumstances, some people want to stand out more than others.”

This is an issue that has evolved over time. At the beginning of 2000, institutions showed that there was dispersion and little discussion among them, while, since 2007, actors have demonstrated a medium-high level of interaction. The level of interaction has increased through the design and implementation of joint projects. For example, the intensity of existing relationships between tourism development institutions and general economic development institutions is considered as medium-high. The nature of this relationship is mainly attributed to infrastructure projects (see

Table 3).

Relationships between tourism development institutions/organizations are motivated by the exchange of information and experiences; the design and execution of plans, programs, policies, and projects; and training actions (

Table 3). In particular, the institutions for which the most interviewees reported high levels of interaction were the Subsecretary of Tourism of Medellín (73%), the Department of Tourism of Antioquia (53%), and the Medellín Chamber of Commerce (53%). The role played by the Medellín Chamber of Commerce is striking, as its importance is ranked at the same level as the regional government. This can be explained by the low political continuity reported in the case of the government of Antioquia. In fact, the political continuity at the regional level, in the context of Antioquia, has been due to the Medellín Chamber of Commerce, ensuring the sustainability of actions, projects, and partnerships.

In some areas, institutions/organizations have formed partnerships through formal relationships (work tables, committees, councils, etc.); these partnerships were 65.13% local (municipal level), 61.11% regional, and 57.80% national. Although relationships in the public sphere stand out as being formal, private organizations also often work together through such relationships. Over the years, they have established formal agreements and alliances that have made tangible progress through economic resources and projects.

Institutions/organizations interact informally (through personal relationships, casual meetings, sporadic meetings), but evidence shows that, in the period 2000–2015, 87.50% of participants belonged to some formal space (e.g., regional council, committee, sectoral table, etc.). According to 45% of participants, these formal spaces allow for more efficient coordination in everything that takes place at the destination.

The pattern of exchanges and frequency of interactions were described as intense. Participants reported that their frequency of interaction with public institutions (government of Antioquia, Medellín Mayor’s Office, Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism, ProColombia) was between two and three times a month (

Table 3). This dynamic is also reflected in private institutions (Chamber of Commerce, federations, and unions). On the other hand, patterns of interaction were seen as considerably low in regard to the frequency of making contact among tourism stakeholders and other key players for innovation, such as technological centers, which participants reported having interacted with only once a year.

In these dynamics of interaction, collaboration and cooperation between the public and private sectors have been described repeatedly in the discourse by regional tourism stakeholders and strategic plans formulated during 2000–2015. The potential of these alliances has led to transformations that have been key to economic development, primarily based on the creation of an institutional fabric.

5.3. Structures of Domination and/or Patterns of Coalition

This element considers leadership and the coordination processes that take place in the destination, along with the power relations. In the case of Antioquia, this indicator has been determined by three factors: the role of each institution, the budgetary resources available, and the stakeholders’ perceptions of those who have the power at the destination.

First, the role played by each institution/organization is determined by its founding objectives, and sometimes these functions can influence the level of power that one actor can have over another; for instance, in legislative terms in the case of public institutions, in terms of competitiveness in the case of associations or universities, or in terms of economic impact and employment in the case of companies. However, the formal mission of each institution/organization is not always related to what happens in reality. In Antioquia, one of the negative aspects related to the creation of a large institutional atmosphere has been the duplication of functions, such as in situations where a certain institution plays a role that does not match its original functions. In the case of Antioquia, respondents reported this phenomenon as a reality. There is fragmentation in the roles played by some actors. For instance, a case emerged with the creation of a network of tourism corporations at the regional level, which took on the role of the government of Antioquia in the municipalities without any prior agreement, and this caused friction and confusion in the regional governance destination.

Second, economic resources play a fundamental role in power dynamics. In this sense, Antioquia shows a high degree of domination exercised by public institutions. From the point of view of the allocation of resources, each participating public institution allocated between USD 36,000 and 200,000 for tourism development of the region in 2015, while each private institution allocated less than USD 36,000. Nevertheless, 48% of institutions and organizations stated that their budgets increased over time (since the year of creation).

Third, the perception of actors who are related to the destination stands out in terms of the spatial scale. In the case of Medellín, a key player and leader in the tourism development of the city has been the Medellín Convention and Visitors Bureau. This institution set the agenda of the city in its function as a business destination and led the city’s internationalization strategy. Therefore, it is an agent that exercises power in defining tourism policies of the city. Regionally, perception favors the Medellín Chamber of Commerce as an actor that has representation and recognition and clear guidance to implement projects with a strong impact on the competitiveness of the destination. On the other hand, actors such as universities or training centers cross-cut the others; that is, they have no power over other actors, but their existence is fundamental for the sector to build regional capacity through knowledge and innovation.

Finally, patterns of coalition refer to governance structures that result in collective representation of what are normally individual and/or sectoral interests. These spaces are established as collective representative places through formal mechanisms that allow the objective as a tourist destination to be achieved (

Table 4).

These spaces of coalitions are identified as sectoral consultation bodies that ensure the participation of all stakeholders in important decisions made about the destination. These spaces have established a collective vision of regional tourism development and have determined the standards and frameworks.

5.4. Mutual Awareness and/or Common Agendas

Mutual awareness and common enterprise imply that institutions collectively develop a common agenda, which may be formally defined or simply represent a set of clear, shared regional priorities [

55]. From there, the three most important alliances and the four most key institutional actors in the building of tourism regional development common agendas were the following:

The Government of Antioquia and the Regional Competitiveness Council, which defined a vision for the region’s economic and social development;

The Medellín Chamber of Commerce, which recognized the need for the diversification of the regional economy and developed the “Cluster Community” in partnership with the Medellín City Council; and

The Medellín City Council, which strengthened the tourism sector by collaborating with partners to improve the attractiveness of the capital city and, in turn, the entire region.

In general, actions undertaken from those processes are related to the elaboration of a common vision, the development of a regional competitiveness strategy, and the promotion of the region and the capital city as a tourism destination. At the same time, the key issues of common agendas focused on developing public policies, defining roles, accessing funding, and attracting investment. From our analysis, interviewees argued that existence of common agendas and institutional empowerment have been key for Antioquia’s regional tourism development. However, there has been a persistent perception that the efficiency and thoroughness with which they have been implemented have been suboptimal. Consequently, although it is recognized that common agendas have clearly been established, 42% of institutions and organizations considered institutional coordination to be inefficient, particularly at the regional level (see

Table 5).

Table 5 shows the types common management tools developed by participating institutions at regional and city level. Such results highlight the disparity between the region and capital city in terms of the effectiveness and efficiency of tools for managing local as well as regional development. The efficiencies of those tools relate closely with institutional performance and political stability in the territory. In that sense, participants stressed the importance of developing agendas that transcend political and electoral timeframes as well as facilitate the continuity of objectives established jointly by the public and private sectors.

6. Discussion

The conventional thinking about the relationship between tourism and regional development is present in a wide range of studies [

56]. Some academic research focuses on the local, place-based factors that influence tourism development and ask why some tourism areas develop more than others. Debates on regional development evidence the importance of institutions to explain differences between regions [

27,

39,

51] and can be applied to regional tourism development.

From the institutional perspective, globalization is producing new forms of regional differentiation and tourism is a key driver to this, with attention focused on the regional level as a key scale of economic organization [

57]. The economic success of a region is highly dependent on the local and sectoral institutional setting and the framework of governance in which the regional economy is embedded [

58,

59]. This concept of embeddedness has been particularly influential in directing attention to the social and institutional factors that shape the processes of economic development in particular places [

3,

60,

61]. This approach highlights the importance of developing strategic governance and networks in order to envision region-promoting collective action, thus generating institutional and political forces to act [

42]. In the case of Antioquia, this argument is supported by evidence of collective action and institutional efforts to develop a long-term vision for the region. Since the early 2000s, Medellín and Antioquia have made very important transformations in its institutional and governance structures [

50], making a positive impact on tourism governance through the establishment of new institutional structures, by applying policies for tourism development, by defining resources and rules, and also through coordination and cooperation among numerous actors including all the institutions and individuals. All of this is key according to previously stated evidence provided by, e.g., Beritelli et al., [

34] and Ruhanen et al., [

35].

On the other hand, the evidence collected also reflects that in Antioquia private organizations have gained power and are capable of deeply influencer the decisions made by government. This is the case, for instance, of Medellín Chamber of Commerce and private tourism associations (Cotelco, Anato, Fenalco). This dynamic is directly related to the arguments expressed by Dredge and Whitford [

62] based on the idea that pre-existing institutional structures and underlying power structures determine outcomes in tourism governance. This also relates to Valente, Dredge, and Lohmann [

63] statement that regional tourism organizations established and led by business actors are more effective in leading regional tourism development.

Through the institutional thickness concept, Amin and Thrift [

3] stated that institutions generate greater legitimacy by nurturing relationships of trust, by stimulating entrepreneurial capacity, and by consolidating the empowerment of economic activity in a local environment. This argument relates regional development success to the plurality of interacting actors through a strong institutional presence and high levels of interaction. In this respect, as the empirical evidence shows, this dynamic represents a fundamental element in the development of tourism in Antioquia. However, as Rodriguez-Pose [

39] argued, and as it can be applied to regional tourism development in Antioquia, while institutions are essential for regional tourism development, implementing regional development strategies based on institutions must confront the problem of the lack of a definition of effective institutions.

Figure 6 graphically summarizes the key variables related to the dimensions of institutional thickness and the dynamics within the institutions in the region of Antioquia. This figure was created following the elements proposed by Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43], and it is of interest in order to analyze the effect of each dimension on: (a) the weight of institutions versus organizations; (b) the multiscalar impacts; (c) the dynamic perspective; and (d) thick versus thin. Distinction between lines represents the intensity of these elements, relates each component developed by Amin and Thrift [

3] with each element conceptualized by Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43], and provides an overview of the institutional framework. Therefore, the main results presented in

Figure 6 can be understood as follows.

First, regarding institutional density, the main results obtained point out a greater presence of private organizations involved in tourism development in the region. According to the multiscalar perspective, the institutions/organizations that have the greatest influence on the destination encompass a sphere of regional influence, and their functions and actions impact the entire region.

In addition, the results show that the region had a positive evolution during the period 2000–2015 and participants attributed this evolution to the creation of a new institutional/organizational fabric. In this sense, Hypothesis 1 (H1) was confirmed as there is evidence that institutional development has played a significant role in regional tourism development. In fact, participants felt that this new fabric has improved the governance of the destination.

In regard to interactions, this analysis has identified how interactions and relationships are largely influenced by the motivation of each institution/organization to interact with others. In this sense, institutions represent higher levels of interaction than organizations. This dynamic can be explained by the fact that their public nature requires constant interaction with local, regional, and national private stakeholders. However, particular attention needs to be paid to the functions they play and the incentives they provide [

43].

The way in which institutions are interrelated specifies that formal interaction spaces are mostly used by local institutions/organizations, while interactions on a national scale take place through informal interaction spaces. This is an important point according to Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero [

43], as far as according to them regional development is shaped not only by interactions among local actors, but also by linkages between local and nonlocal actors. For this reason, organizational network analysis should include national and global actors and the evolution of their interactions over time. In this respect, the evolution of interactions in Antioquia has been positive, as many of the participants in the study claimed to belong to different formal and informal interaction spaces during 2000–2015. This engagement is clearly relevant to generate collective learning processes and networking in the region [

64], confirming Hypothesis 2 (H2). So, institutional interactions shape the extent of regional tourism development.

Regarding the power dimension, not all institutions/organizations are equally important for regional development and innovation [

65]. Political economy theories on why some regions are successful while others fail in achieving development emphasize the importance of power relations [

66]. In Antioquia, the findings show that certain actors can play a decisive role in regional tourism development, whether this is influenced by a greater allocation of economic resources or strong leadership and interaction capacity in relation to other institutions/organizations. In this analysis, the power shift is largely determined by regional institutions, but it is important to clarify that, in the context of Antioquia, the power is determined by a greater availability of economic resources for institutions. Proof of this is that institutions/organizations at the national level have less relevance in the process of regional tourism development, at least in the case of Antioquia where governance capability is strong. This is a significant dynamic that could clearly change depending on the context of the place. Nevertheless, in the Antioquia context, changes of power between institutions/organization appear to be minimal, preventing a low balance in the distribution of power. Identifying this dynamic is valuable in order to determine which institutions/organizations at which geographic level have the most power to influence regional development, and to what extent, how, and why the power balance changes over time [

43]. In addition, determining the distribution of power across the political landscape is crucial for an understanding of the changes in institutions and their effects on the policy environment for economic development [

66]. Finally, in Antioquia, the power to influence policies or institutions in regional tourism landscape is often related to leadership through spaces of coalitions that ensure the participation of all stakeholders in important decisions. This collective participation has been more effective than the role of the structures of domination. Therefore, this means that the Hypothesis 3 (H3) could also be confirmed.

The fourth and last characteristic that defines institutional thickness is the development of a common agenda. In Antioquia, interviewees argued that the existence of common agendas and institutional empowerment has been key for regional tourism development, confirming the Hypothesis 4 (H4). At the same time, it has been proven that common agenda operationalization is usually more efficient when it is carried out by entrepreneurs and not by institutions/organizations [

63]. This also demonstrates the decisive role of entrepreneurs in triggering positive changes in the evolutionary trajectory of the destination [

67]. The design of development plans and strategic/sector plans is the most frequent pattern for implementing common agendas. However, implementation depends on changes in the regional and local political context. This reaffirms the idea that common agendas are influenced by the specific patterns of domination and relative power [

68].

7. Conclusions

This paper argues that institutions are important drivers for regional tourism development and highlights the relevance of institutional thickness as concept for research.

Institutional thickness, as initially theorized by Amin and Thrift [

3], is considered a key condition to promote economic development and mobilize actors, organizations, and resources. This approach provides valuable insight into the four factors (strong institutional presence, high levels of interaction between institutions, a mutual awareness and common enterprise among institutions, and the existence of structures of domination and/or patterns of coalition) that can influence the social and economic performance of a place according to them.

Academic literature shows that institutional thickness has been investigated according to different perspectives until now. However, efforts have been made to build empirical frameworks [

21,

42,

43,

64,

65,

68,

69] mainly in developed countries and industrial activity contexts, gaps exist in the study of how different institutional scenarios affect regional growth and on how they contribute to this according to the type of economy [

70].

In this study, we attempted to address this gap by applying the four constitutive features of institutional thickness in a developing region and regarding its evolution, transformation and development as tourism destination. This connects our analysis with recent approaches on analyzing the dynamics of a destination from Evolutionary Economic Geographies approaches [

7]. This is also relevant as within the economic development models adopted by the Latin American and Caribbean countries in which tourism plays a relevant and strategic role, the growing demand to develop tourism is also reflected in the wide range of institutions supporting this sector [

71].

In doing so, this analysis follows the enormous work done in recent years by social scientists to try to understand the role of institutions in economic development [

72]. Bearing in mind that there are other cross-cutting factors that influence regional tourism development, this analysis proposes an empirical application based on the institutional thickness approach not only to determine the ways in which a strong institutional atmosphere influences regional tourism development, but also to learn what aspects can determine its efficiency.

The empirical approach has produced an interesting assessment allowing us to observe the role played by institutions in regional tourism development and the dynamics among the agents involved in this process according to the four factors of institutional thickness. This approach provides a new perspective on the role of institutions in regional tourism development in Latin America, particularly in Antioquia, Colombia, one of the most prosperous regions in the country. Besides, the proposed methodology provides insights to introduce this analytical framework in other regions with similar geopolitical and economic dynamics. Studying and characterizing the nature and relationships of institutions in such geographical contexts can lead to better management and planning of tourism destinations considering issues such as governance, coordination, leadership, and the establishment of common agendas, and enrich the debate on the subject.

Overall, confirming the initial hypothesis, the paper highlights that the concept of institutional thickness can accomplish a valuable synthesis of diverse and often disconnected arguments to account for regional tourism development as it can also make it when accounting on regional economic performance [

42]. Therefore, based on our empirical application, we highlight the following lessons.

First, institutional thickness may explain why qualitative matters are important in regional development as relationships between regional institutional stakeholders and motivation for joint action are relevant in assessing regional performance beyond traditional quantitative factors. Second, issues related to political governance are clearly related to institutional thickness. For instance, we found that this aspect has been relevant in the case of Medellín and Antioquia, where “good governance” has also been coordinated with institutional and organizational factors. Third, the development pace of institutions in the case analyzed also show that exogenous factors can have an important influence too [

66]. Fourth regional development changes take place partly due to changes in institutional frameworks (e.g., policies, legislation, and budgets), and, in this scenario, some institutions are more prominent than others in different phases of the development process [

73]. This consideration is reflected in our results, showing that public institutions play a key role, principally determined by their financial capacity, but also reveal that organizations such as the Medellín Chamber of Commerce is playing a strong leadership when public institutions or regional government does not assume that role.

Obviously, future analyses may be required to propose other indicators and methods for measuring the role of institutional thickness in regional tourism development. In this respect, considering the important role and the different sides of the interactions between institutions probably social networks analysis could be useful for this purpose, as far as networks analysis extends beyond the attributes of individual actors and can evidence how they are positioned within a system [

74].

Finally, we highlight that this paper contributes to the discussion about the role of the recent institutional and economic developments in some Latin American regions specifically in the tourism landscape demonstrating the usefulness of institutional thickness and opening a new window for future applied research to tourism regional development. From a managerial perspective, the results also suggest that the development of institutions and organizations focused in this specific sector is a convenient tool to stimulate, accompany and create a common vision for the tourism industry at regional scale.