Empirical Identification of Latent Classes in the Assessment of Information Asymmetry and Manipulation in Online Advertising

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- •

- Are e-consumers aware of information asymmetry and manipulation in advertising?

- •

- Do latent data affect e-consumers’ (respondents’) declared answers, and how?

Previous Literature and Research

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Method

- Introductory questions about experiences and ways of using the Internet regarding the frequency and extent of social networking, online shopping, and goals and rationale for using the Internet.

- Rating the intentions of advertisers and the advertising message in light of their own experience and presence in the world of online advertising.

- Evaluation of the impact of advertising on the e-consumer in the context of individual and social assessments.

- The subjective perception of the role of advertising in the process of online shopping.

- Evaluation of respondents’ knowledge in the field of online marketing and their digital competences.

2.2. Participants

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

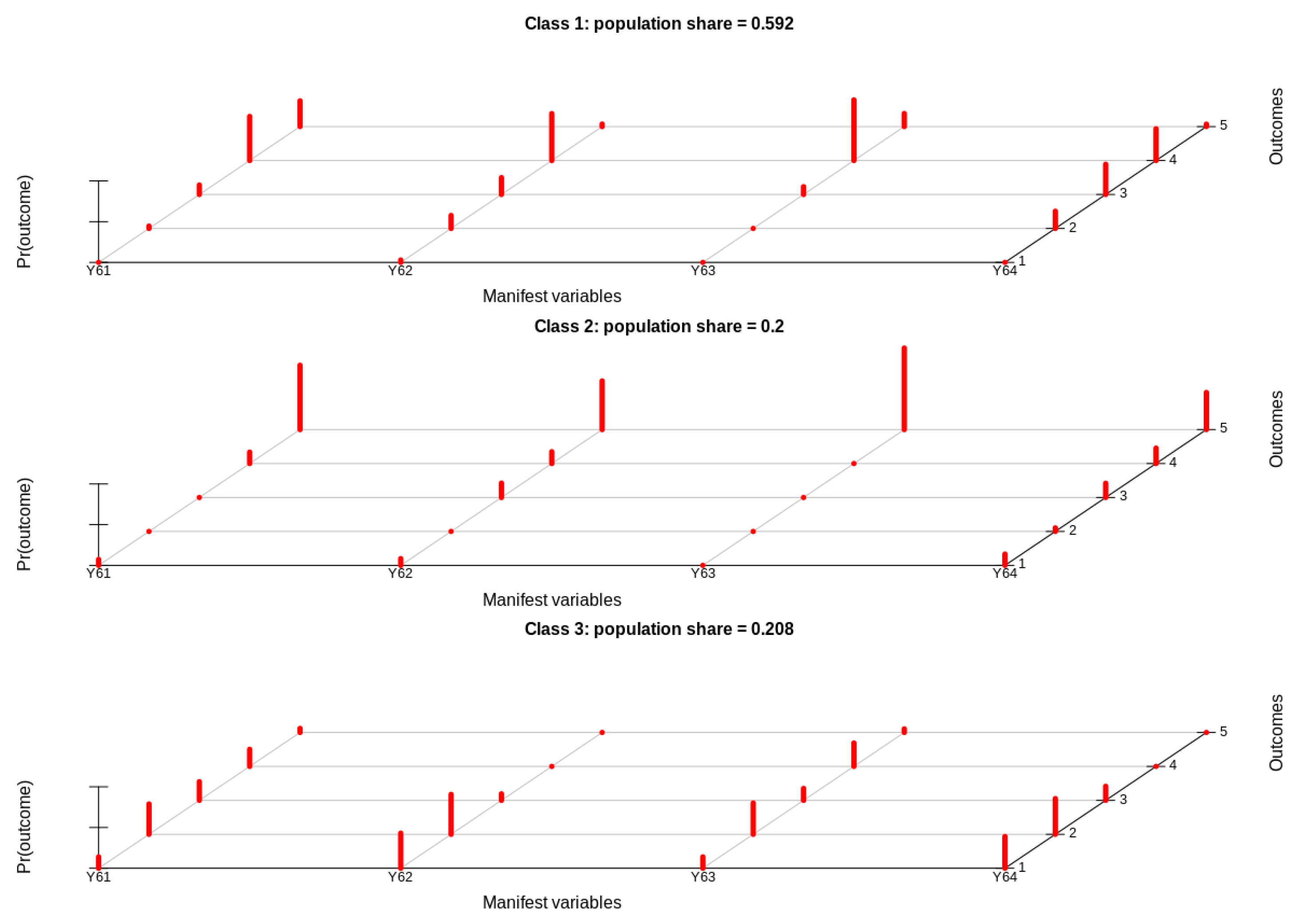

3.2. Empirical Findings

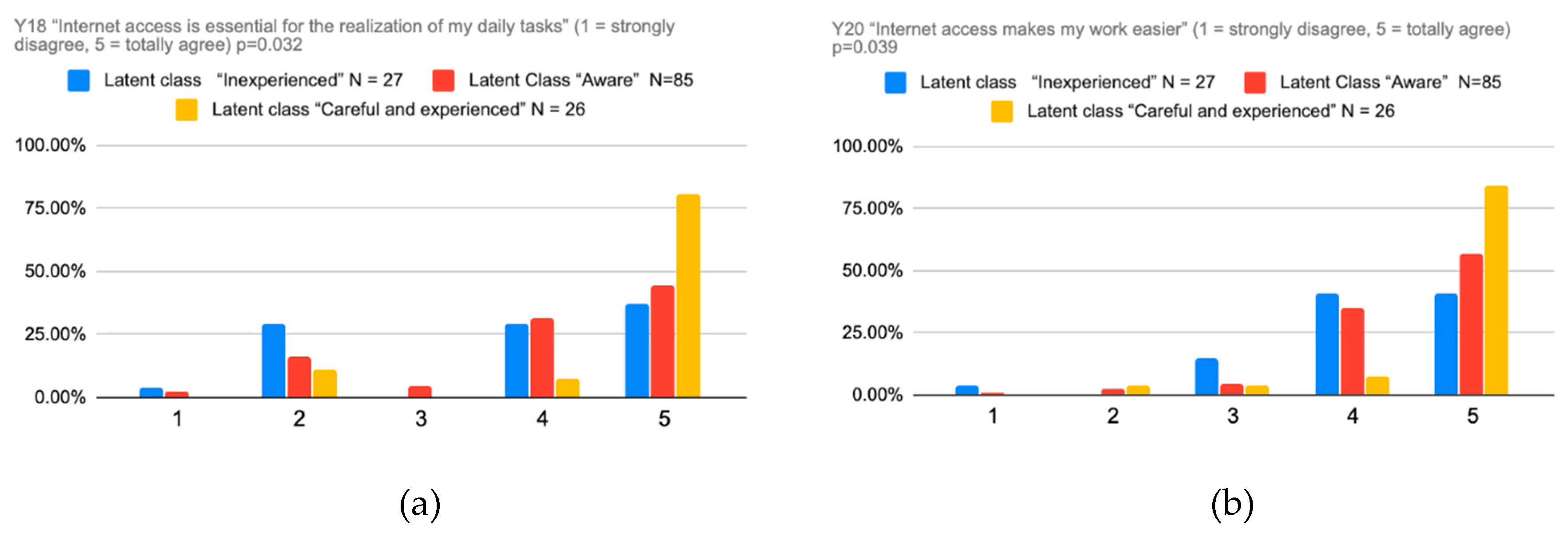

- Professionalization of Internet use (Y18, Y20).

- Trust in social proof of rightness (Y22, Y28, Y32, Y53).

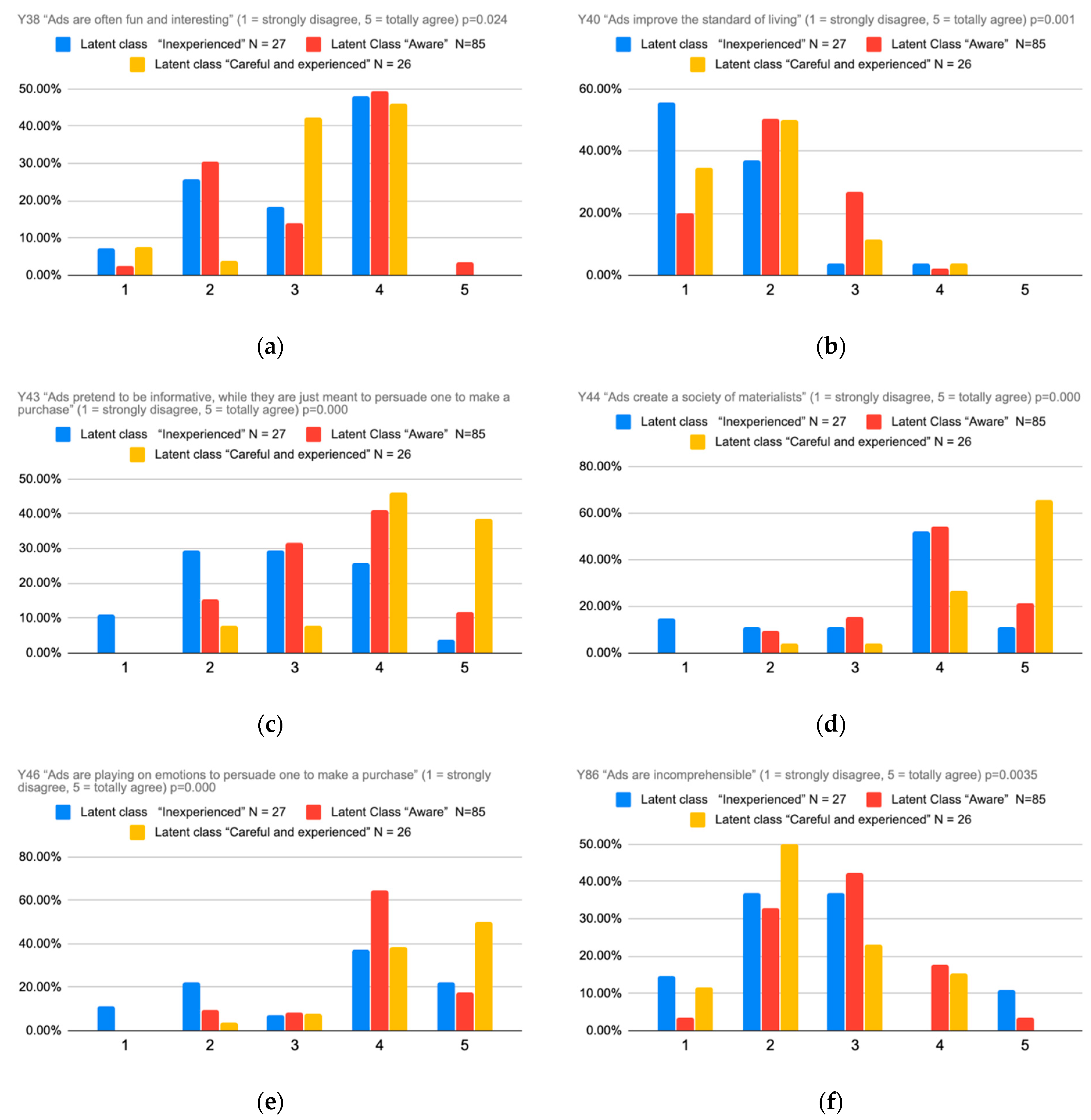

- Attitude towards online advertising (Y38, Y40, Y43, Y44, Y46, Y86).

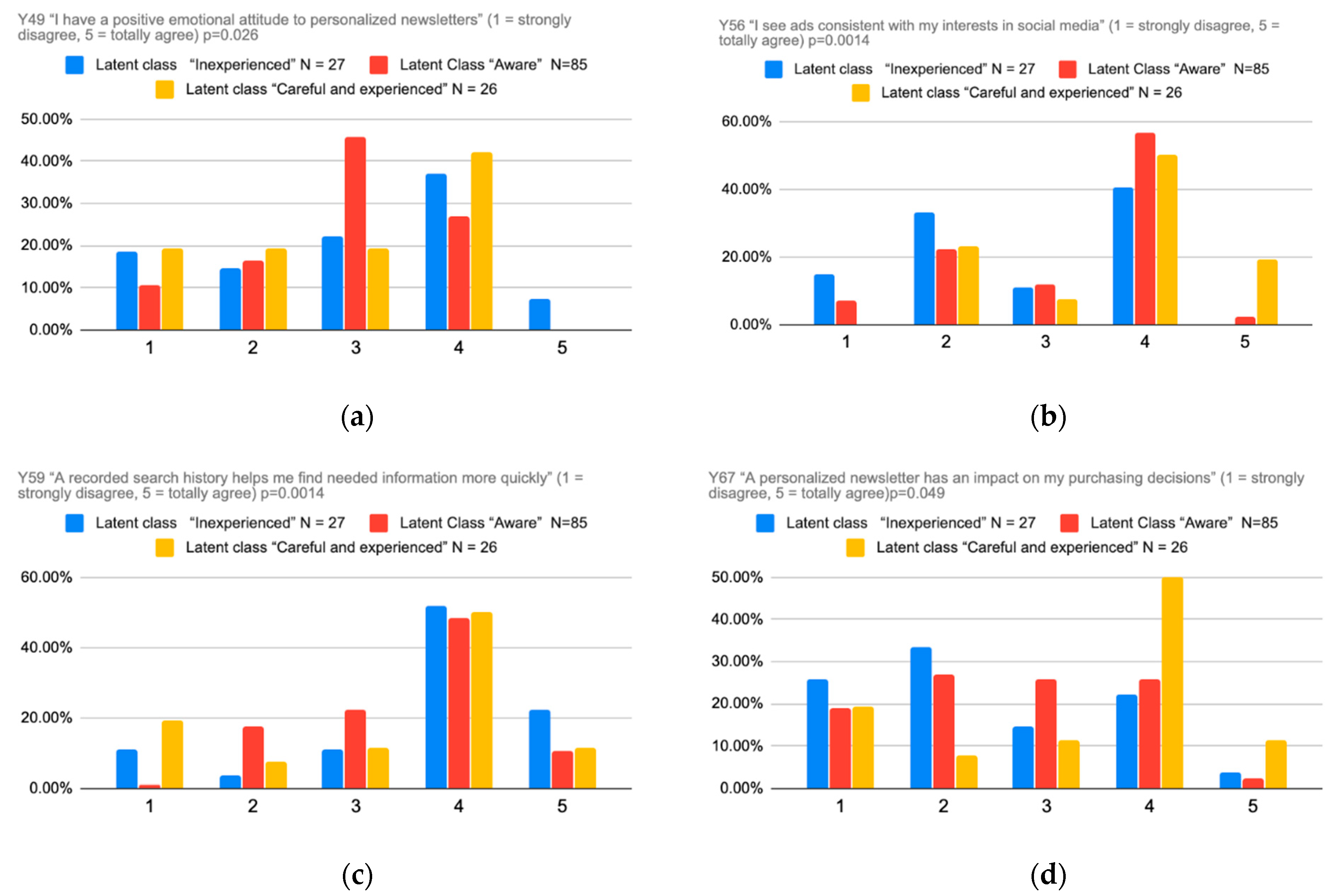

- Attitude towards personalization of online advertising content (Y49, Y56, Y59, Y67).

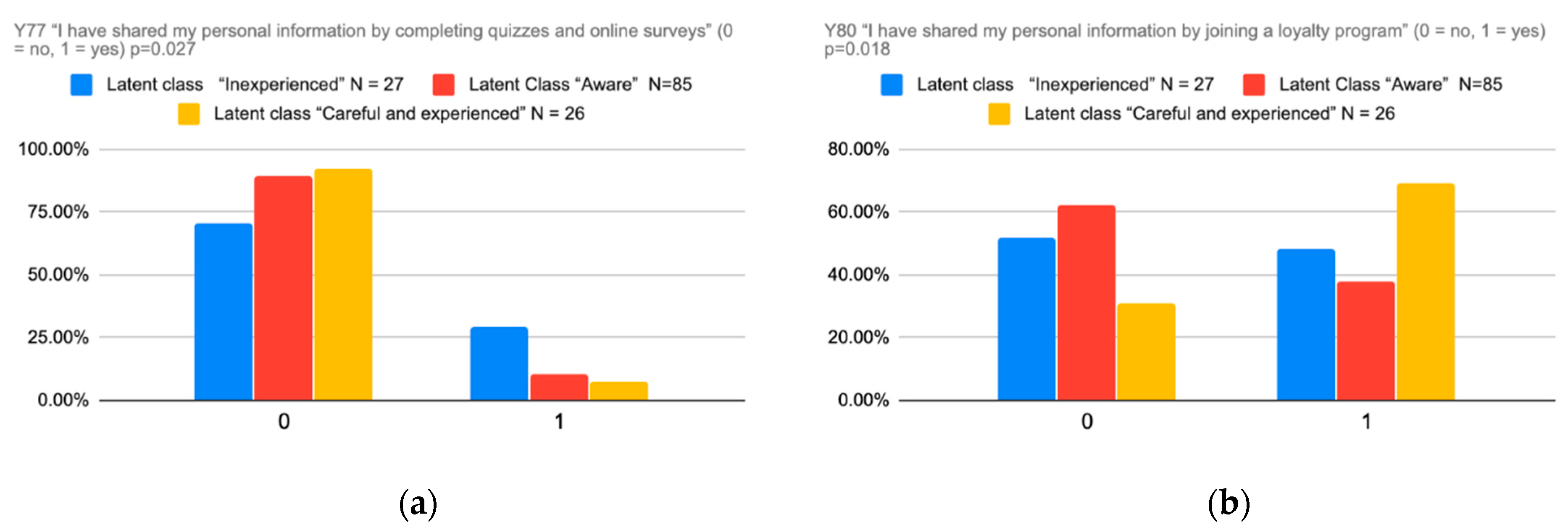

- Willingness to share personal information online (Y77, Y80).

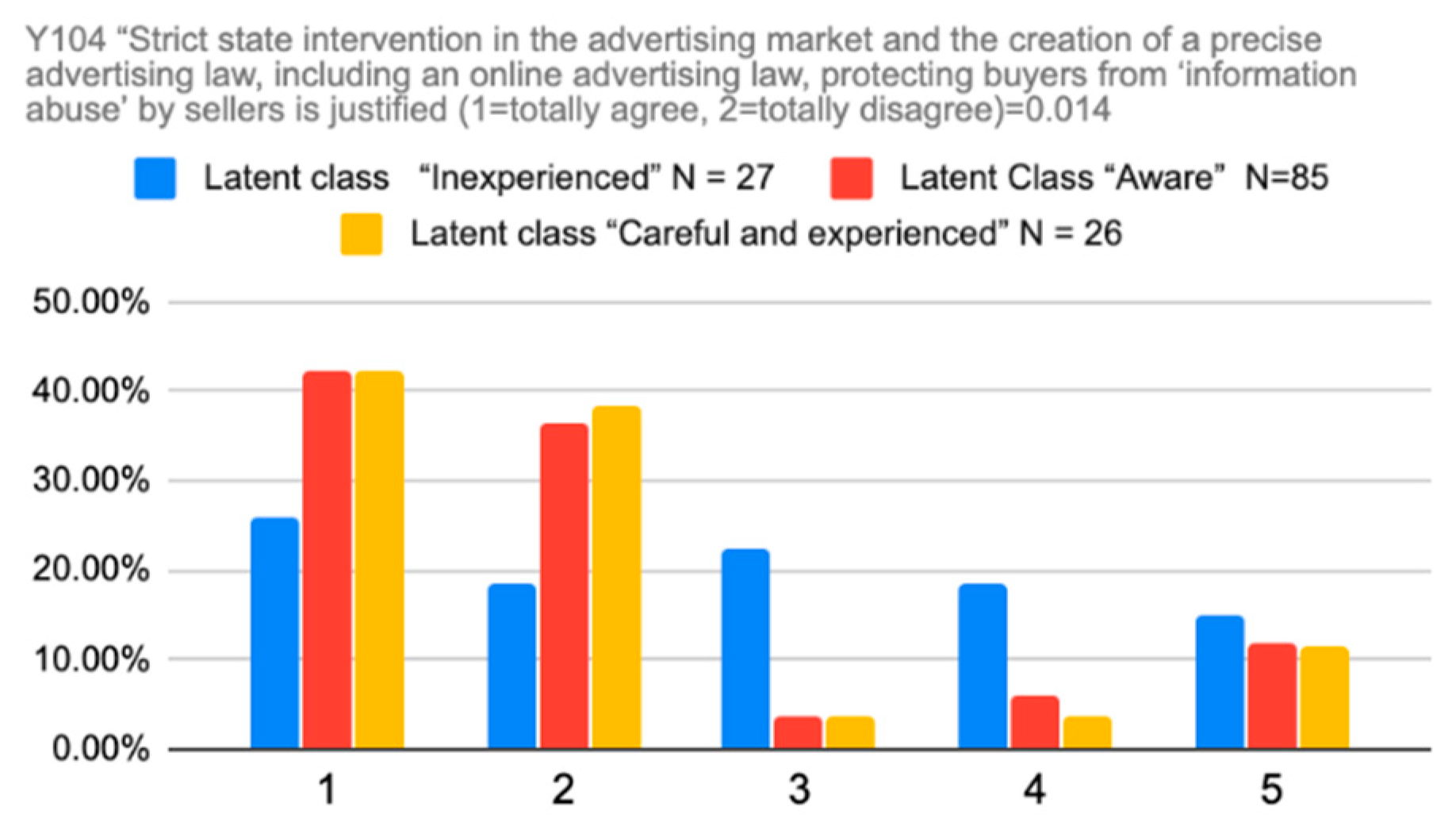

- Attitude towards state intervention in the regulation of online advertising (Y104).

4. Discussion

“Just as our computers need protection against malware, so too we need protection against phishing for phools more broadly defined”.[75]

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LaTour, M.S.; LaTour, K.A. Positive mood and susceptibility to false advertising. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trivedi, K.; Trivedi, P.; Goswami, V. Sustainable Marketing Strategies: Creating Business Value by Meeting Consumer Expectation. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Certified, B. Corporation. Available online: https://www.bcorporation.net (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Gordon, R.; Carrigan, M.; Hastings, G. A framework for sustainable marketing. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.; Komiyama, H.; Takeuchi, K. Sustanability Science: Building a new discipline. Sustain. Sci. 2006, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- SDG—2030, Action Agenda (AAAA). Available online: http:/www.un.org./esa/ffd.wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAAAOutcome.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Aaker, D.A.; Stayman, D.M. Measuring Audience Perceptions of Commercials and Relating Them to Ad Impact. J. Advert. Res. 1990, 30, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, L.; Lewis, C.; Auty, S.; Buijzen, M. Is Children’s Understanding of Nontraditional Advertising Comparable to Their Understanding of Television Advertising? J. Public Policy Mark. 2013, 32, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. Factors Affecting Cognitive Resistance to Advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Friestad, M.; Boush, D.M. The Development of Marketplace Persuasion Knowledge in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. J. Public Policy Mark. 2005, 24, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettel, M.; Spilker-Attig, A. Online advertising effectiveness: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2010, 4, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, Y.G. Identifying key factors affecting consumer purchase behavior in an online shopping context. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanak-Kosmowska, K. Rola Serwisów Społecznościowych w Komunikacji Marketingowej Marki; Wydawnictwa Drugie: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chapoton, B.; Régnier Denois, V.; Nekaa, M.; Chauvin, F.; Flaudias, V. Social Networking Sites and Perceived Content Influence: An Exploratory Analysis from Focus Groups with French Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.C.; Kim, Y. Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic world-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.H.; Kartajaya, H.; Setiawan, I. Marketing 4.0. Moving from Traditional to Digital; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.H.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management; Pearson: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Ogilvy on Advertising in the Digital Age; Carlton Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, E. The Social Animal; Worth/Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, D. The Network Society. Key Concept Series; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, G.; Tkaczyk, J. (Eds.) The Impact of the Digital World on Management and Marketing; Poltext: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, M. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Pratkanis, A.R.; Aronson, E. Age of Propaganda: The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, C.H. Digital Human: The Fourth Revolution of Humanity Includes Everyone; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R. Influence. Science and Practice; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Danciu, V. Manipulative marketing: Persuasion and manipulation of the consumer through advertising. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2014, 21, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Geuens, M.; Van den Bergh, J. Marketing Communications. A European Perspective; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foxall, G.R.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Brown, S. Consumer Psychology for Marketing; Thomson: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, R.H.; Seiter, J.S. Persuasion: Social Influence and Compliance Gaining; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; MacMillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvy, D. Ogilvy on Advertising; Carlton Books: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Perloff, R.M. The Dynamics of Persuasion: Communication and Attitudes in the Twenty-First Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, S.; Thorson, E. Advertising Theory; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn, M. Kommunikationspolitik, Systematischer Einsatz der Kommunikation für Unternehmen; Verlag Franz Vahlen: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in Hypermedia Computer-Mediated Environments: Conceptual Foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minton, E.; Lee, C.H.; Orth, U.; Chung-Hyun, K.; Kahle, L. Sustainable Marketing and Social Media. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, J.; Busch, M. Marketing-Kommunikation in Online-Medien. Market. Z. Forsch. Praxis 1997, 19, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, J.W. Marketing communication in hypermedia computer-mediated environments vs the paradigm of a network society. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2016, 17, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maráková, V. Marketingová komunikácia v cestovnom ruchu; Wolters Kluwer: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiktor, J.W. Komunikacja Marketingowa. Modele, Struktury, Formy Przekazu; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Рoмат, Э.; Сендерooв, Д. Маркетингoвые Кoммуникации; Санккт –Петербуург: ПИТЕР, Russia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Juska, M.J. Integrated Marketing Communication. Advertising and Promotion in a Digital World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle, L.; Dahl, S.; Czarnecka, B.; Lloyd, J. Marketing Communications; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Falkheimer, J.; Heide, M. Strategic Communication: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Percy, L. Strategic Integrated Marketing Communications; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, J.P.; Shen, L. The Sage Handbook of Persuasion. Developments in Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Keer, G.; Richards, J. Redefining advertising in research and practice. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J.D. Persuasion: Theory and Research; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Prislin, R.; Crano, W.D. A history of social influence research. In Handbook of the History of Social Psychology; Kruglanski, A.W., Stroebe, W., Eds.; Psychology Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stiff, J.B. Persuasive Communication; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Geng, S. Detection of Fake Reviews: Analysis of Sellers’ Manipulation Behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doliński, D. Techniki Wpływu Społecznego; Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches; WCB: Des Moines, IA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Roskos-Ewoldsen, D.R.; Fazio, R.H. The accessibility of source likebility as a determinant of persuasion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 38, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.T.; Lane, W.R. Kleppner’s Advertising Procedure; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, G.A. The Market for “Lemons”: Qualitative Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. The Economics of Asymmetric Information; MacMillan Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sandmo, A. Asymmetric Information and Public Economics: The Mirrlees-Vickrey Nobel Prize. J. Econ. Perspect. 1999, 3, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spremann, K. Asymetrische Information. Zeischrift für Betriebwietschaft 1999, 5/6, 561–586. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley Rosser, J.A., Jr. Nobel Prize for Asymmetric Information: The economic contributions of George Akerlof, Michael Spence and Josef Stieglitz. Rev. Political Econ. 2003, 15, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S. The Effect of Asymmetric Information on Dividend Policy. Q. J. Bus. Econ. 2005, 44, 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.; Nalebuff, B. The Art of Strategy: A Game Theorist’s Guide to Success in Business and Life; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forlicz, S. Niedoskonała Wiedza Podmiotów Rynkowych; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski, J.F. Friction et Asymétrie D’information Sur les Marchés D’action; Economica: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Garbe, R. Die Kraft der Informationsasymmetrie in Großen Organization: Immer wieder Prinzipal und Agent; Iger Verlag RWS: Hamburg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Illing, G. Geld und Asymmetrische Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, E. Asymmetrische Information und Werbung; Springer: Hamburg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nestorowicz, R. Asymetria Wiedzy a Aktywność Informacyjna Konsumentów na Rynku Produktów Żywnościowych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ragotzky, S. Unternehmensverkauf und Asymetrische Information; Europäische Hochschulschriften Peter Lang: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N.J.; Phua, J.; Lim, J.; Jun, H. Disclosing Instagram Influencer Advertising: The Effects of Disclosure Language on Advertising Recognition, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intent. J. Interact. Advert. 2017, 17, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reevers, R. Reality in Advertising; Widener Classics: Harvard, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, W.F.; Marks, S.G. Managerial Economics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, G.J.; Shiller, R.J. Phishing for Phools. The Economics of Manipulation and Deception; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, D. Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller; In The Austrian; 2016; Volume 2, pp. 12–14. Available online: https://cdn.mises.org/The%20Austrian%20vol%202%20no%201%202016.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Eagle, L.; Dahl, S. Marketings Ethics & Society; Sage Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz, M. Argumentacja, Perswazja, Manipulacja; Wykłady z Teorii Komunikacji; GWP: Gdańsk, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M.; Friedman, R. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement; Harcourt: San Diego, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein, M.; Markopoulos, P.; De Ruyter, B.; Aarts, E. Can You Be Persuaded? Individual Differences in Susceptibility to Persuasion. Multimed. Modeling 2019, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byung-Do, K.; Srinivasan, K.; Wilcox, R.T. Identifying price sensitive consumers: The relative merits of demographic vs. purchase pattern information. J. Retail. 1999, 75, 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, M.; Cui, G.; Peng, L. Manufactured opinions: The effect of manipulating online a product reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 87, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bosnjak, M.; Tuten, T.L. Classifying Response Behaviours in Web-based Surveys. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2001, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, D.A.; Lewis, J.B. poLCA: An R Package for Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 41, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F. The Interpretation and Mathematical Foundation of Latent Class Structure Analysis; Measurement and Prediction; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F. Latent Structure Analysis. In Psychology: A Study of a Science; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.W. Some Scaling Methods and Estimation Procedures in the Latent Class Model, Probability and Statistics; Grenander, U., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika 1974, 61, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Lanza, S. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Massaglia, S.; Merlino, V.M.; Borra, D.; Bargetto, A.; Sottile, F.; Peano, C. Consumer Attitudes and Preference Exploration towards Fresh-Cut Salads Using Best–Worst Scaling and Latent Class Analysis. Foods 2019, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rost, J.; Langeheine, R. (Eds.) Applications of Latent Trait and Latent Class Models in the Social Sciences; Waxmann Publishing Co.: Munster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.; Murphy, T.B. Bayes LCA: An R Package for Bayesian Latent Class Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amblee, N.; Bui, T. Harnessing the Influence of Social Proof in Online Shopping: The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales of Digital Microproducts. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 114–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.; Mortimer, K. Legislation, regulation and ethics. In Marketing Ethics and Society; Eagle, L., Dahl, S., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2015; pp. 265–272. [Google Scholar]

| Selected Characteristics of the Students | Number of Participants and PercentAges | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 138 | 100% | |

| Sex | Female | 109 | 79% |

| Male | 29 | 21% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 132 | 96% |

| 26–35 | 6 | 4% | |

| Variable | Variable Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Y 61 | “I have the impression that my personal data are often used to create per-sonalized offers” |

| Y 62 | “I feel manipulated by online advertising” |

| Y 63 | “I leave online traces that can be used to manipulate my behavior” |

| Y 64 | “Advertising has an information advantage over me” |

| Template | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|

| One-cluster Model | 1583.32 | 1630.156 |

| Two-cluster Model | 1499.838 | 1596.438 |

| Three-cluster Model | 1449.675 | 1596.038 |

| Four-clusters Model | 1452.034 | 1648.16 |

| Latent Class | Proposed Name | Characteristics of Probability |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aware N = 85 | High awareness of the use of personal data, the sense of manipulation by online advertising, and leaving digital footprints, and a moderate awareness of the information superiority of advertising. |

| 2 | Careful and experienced N = 26 | Very high awareness of the use of personal data, a high sense of manipulation by online advertising, a very high awareness of leaving digital footprints, and greater awareness of the information superiority of advertising. |

| 3 | Inexperienced N = 27 | Low awareness of personal data use, low sense of manipulation by online advertising and leaving digital footprints, and low awareness of advertising information superiority. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanak-Kosmowska, K.; Wiktor, J.W. Empirical Identification of Latent Classes in the Assessment of Information Asymmetry and Manipulation in Online Advertising. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208693

Sanak-Kosmowska K, Wiktor JW. Empirical Identification of Latent Classes in the Assessment of Information Asymmetry and Manipulation in Online Advertising. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208693

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanak-Kosmowska, Katarzyna, and Jan W. Wiktor. 2020. "Empirical Identification of Latent Classes in the Assessment of Information Asymmetry and Manipulation in Online Advertising" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208693