Citizen-Consumers as Agents of Change in Globalizing Modernity: The Case of Sustainable Consumption

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Outline of the Article

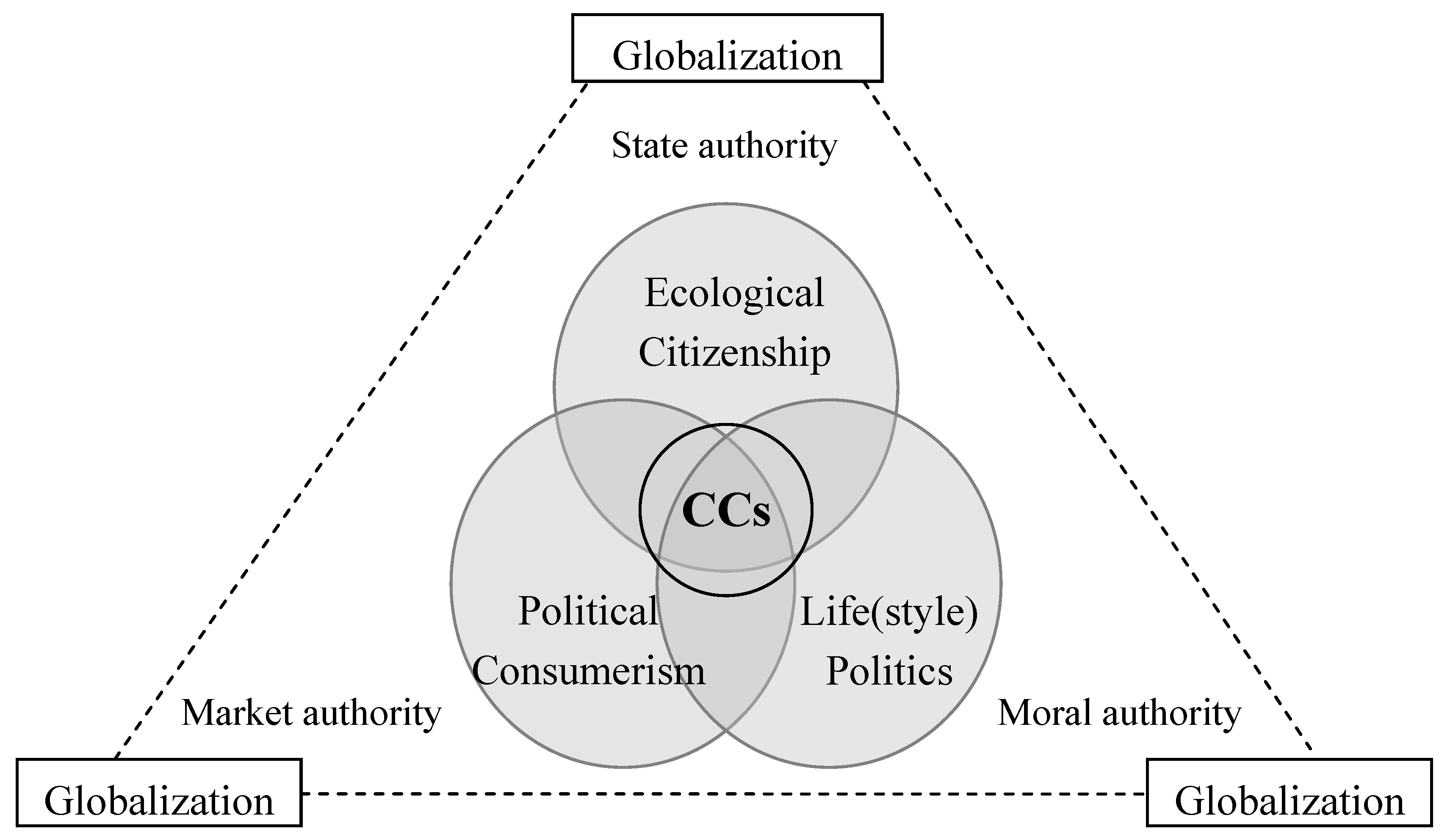

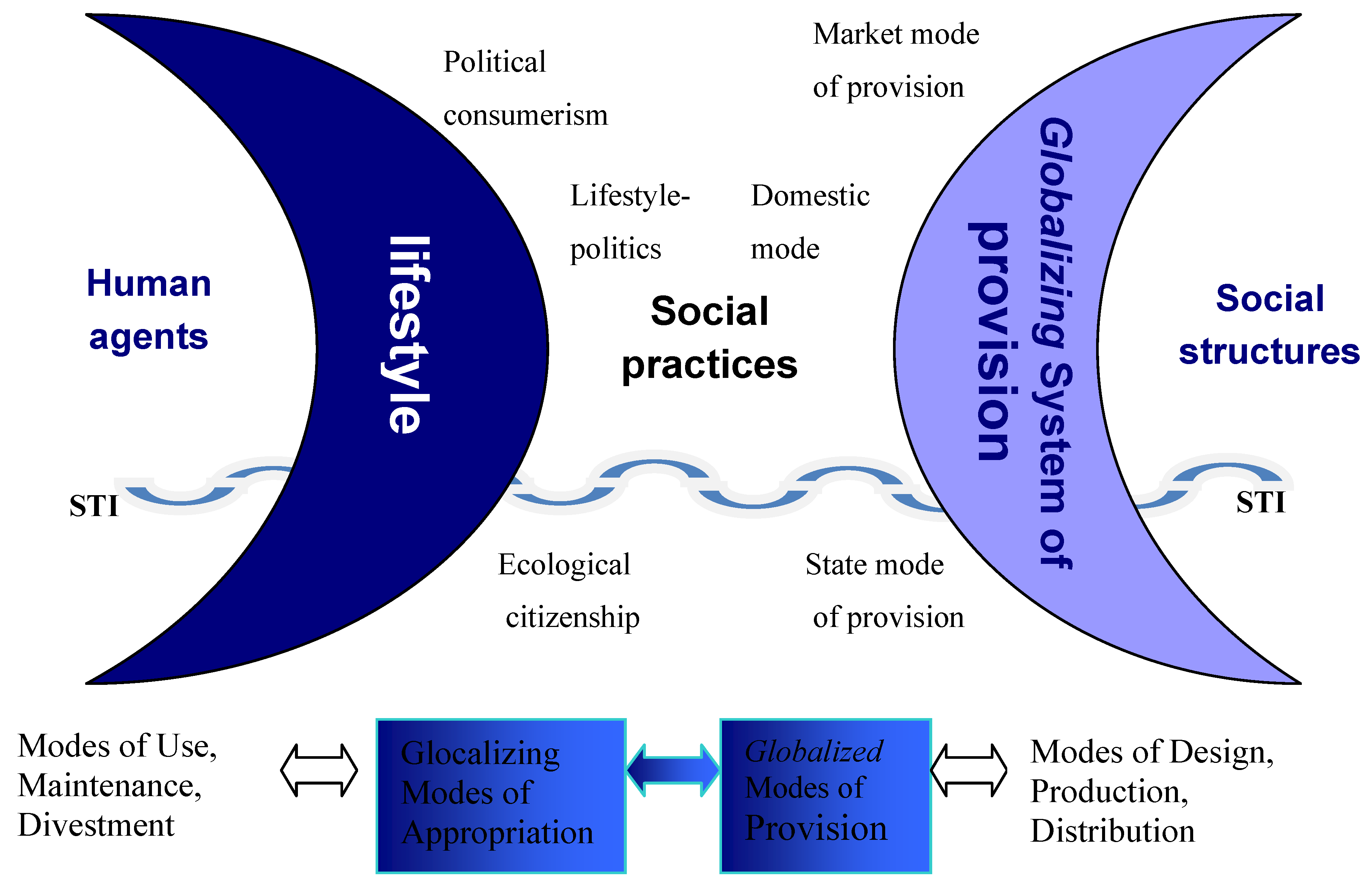

2. Political Roles for Citizen-Consumer in Global Modernity: Three Ideal-Types [2]

2.1. Ecological Citizenship

2.2. Political Consumerism

2.3. Life(Style) Politics

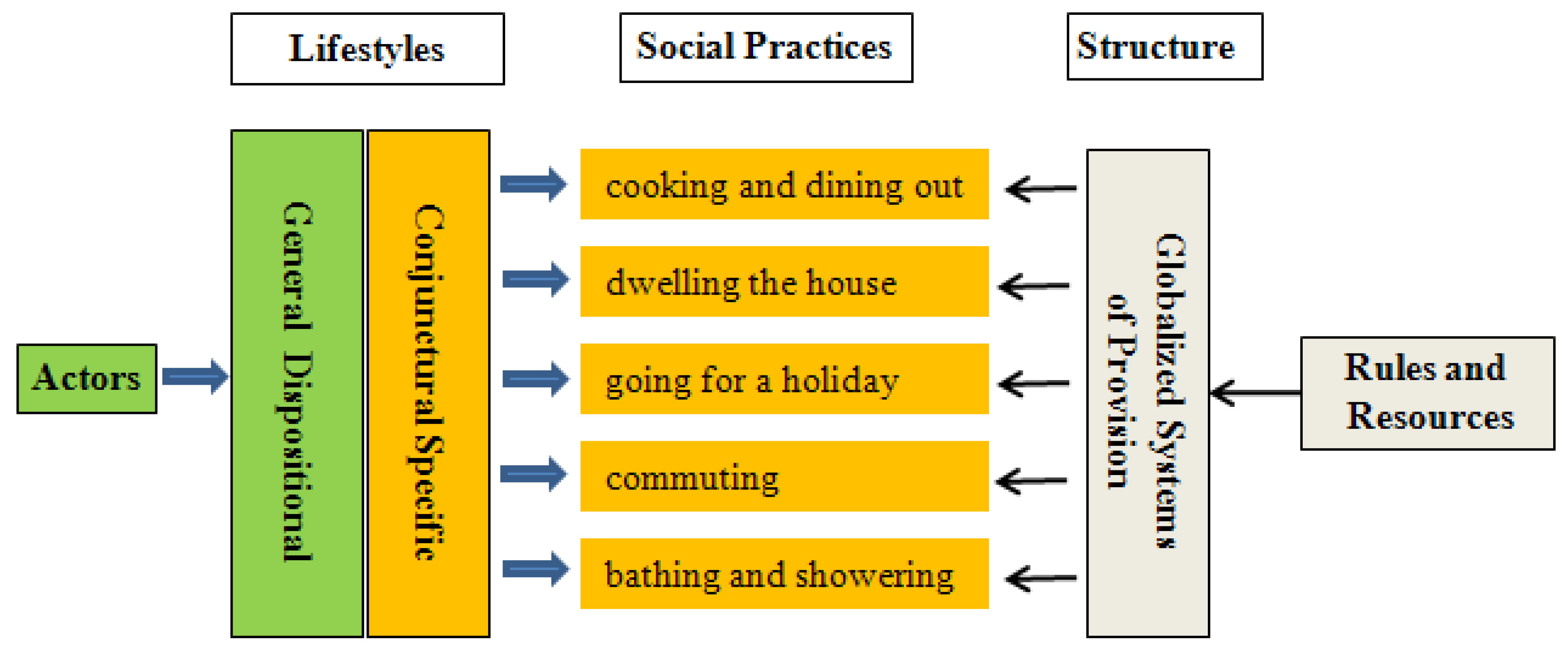

3. Changing Consumption Practices: The Role of Citizen-Consumers

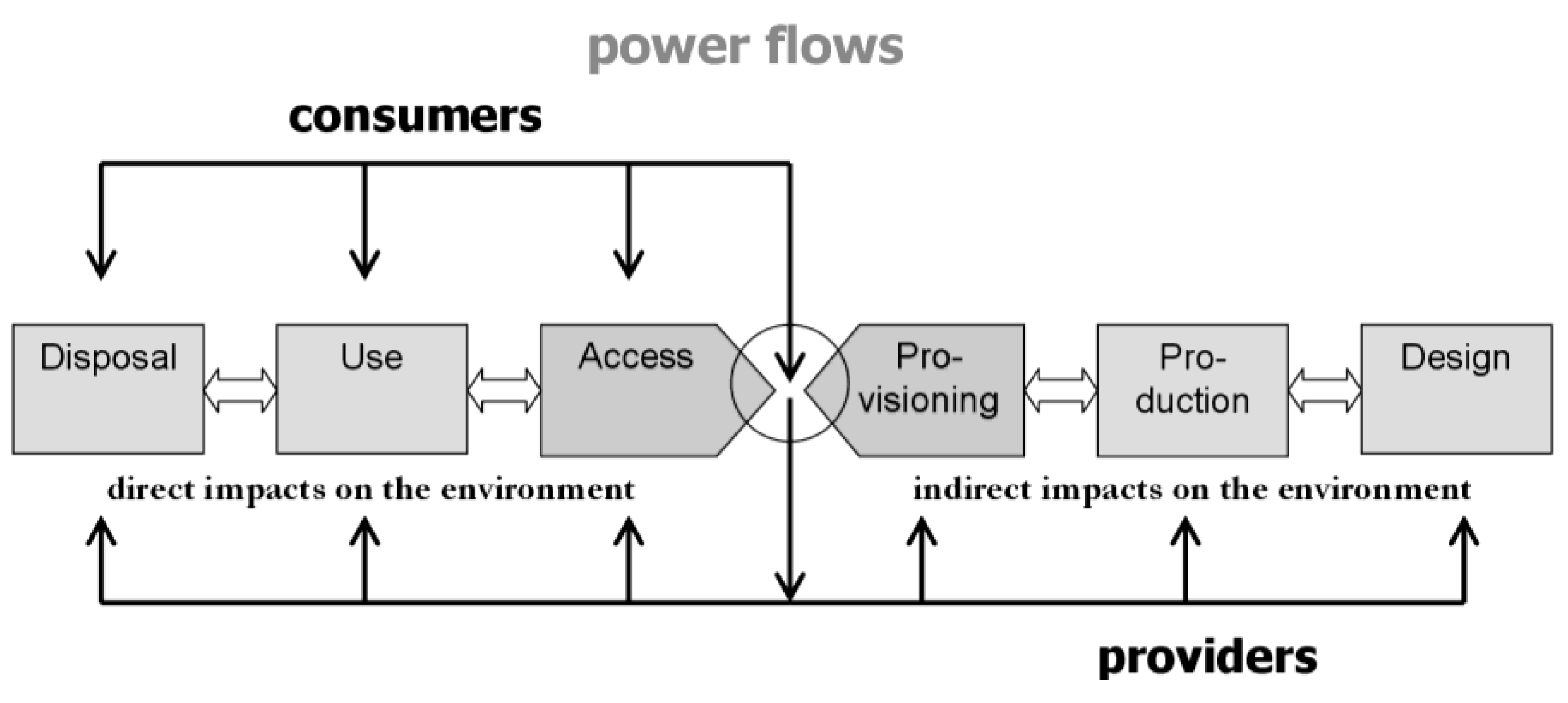

3.1. Agency, Objects, and Technological Infrastructures

3.2. Globalizing Modes of Provision and Corresponding Modes of Appropriation

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgement

References and Notes

- The use of “ideal types” was introduced by Max Weber as a methodology to organize sociological research. Ideal types are “ideal” and not real existing in empirical reality. As frames of reference however they help analyze and interpret empirical reality.

- Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J. Greening global consumption: Redefining politics and authority. Global Environ.Change 2008, 18, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Risikogesellschaft: Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Was ist Globalisierung Irrtümer des Globalismus—Antworten auf Globalisierung; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Power in the Global Age: A New Global Political Economy; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Willms, J. Conversations with Ulrich Beck; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society. In The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Territory-Authority-Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages; Princeton University Press: Princeton, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The main aim of this chapter is to provide an exploratory discussion of the three ideal type roles for citizen-consumers. For a historical analysis of the emerging roles, rights and responsibilities of “citizens” and “consumers” modernity, see The Making of the Consumer; Knowledge, Power and Identity in the Modern World; Trentmann, F. (Ed.) Berg: Oxford, UK, 2006.; and Trentmann, F. Consumers as citizens: Synergies and tensions for well-being and civic engagement. In Rethinking Consumer Behaviour for the Well-being of All—Reflections on Individual Consumer Responsibility; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The turning point in the debate—When modernity became global modernity—Can be situated around 1990, just after the fall of the Berlin wall, at the time that internet technologies boosted the emerging world-network-society [17] and with a wave of privatization and liberalization policies flooding OECD societies.

- Wallerstein, E. The Modern World System I; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Held, D. Democracy and the Global Order; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Held, D.; McGrew, A. The Global Transformation Reader; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Politics of Climate Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Global Civil Society 2001; Anheier, H.; Glasius, M.; Kaldor, M. (Eds.) Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001.

- Global Civil Society 2002; Glasius, M.; Kaldor, M.; Anheier, H. (Eds.) Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002.

- Dobson, A. Environmental Citizenship; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Citizenship; Dobson, A.; Bell, D (Eds.) MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006.

- For John Barry, these duties might even take the form of “Compulsory Sustainability Services”, issued by active green states, and targeting specific (lifestyle) groups of the population. When driving an SUV, you can either pay more (eco) tax or compensate for your sins by longer services… ( Barry, J. Resistance Is Fertile: From Environmental to Sustainability Citizenship. In Environmental Citizenship; Dobson, A., Bell, D., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]).

- Eder, K.; Giesen, B. European Citizenship between National Legacies and Postnational Projects; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- About 60 to 80 percent of all environmental policy measures in The Netherlands originate from the European Union, with similar figures for many other member states of the EU.

- Mol, A.P.J. Environmental Reform in the Information Age: The Contours of Informational Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Authority of the Consumer; Keat, R.; Whiteley, N.; Abercrombie, N. (Eds.) Routledge: London, UK, 1994.

- Southerton, D.; Warde, A.; Hand, M. The limited autonomy of the consumer: Implications for sustainable consumption. In Sustainable Consumption: The Implications of Changing Infrastructures of Provision; Southerton, D., Chappells, H., Van Vliet, B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser, E. Fast Food Nation: What the All-American Meal is Doing to the World; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nestle, M. Food Politics; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pollan, M. Defense of Food; The Myth of Nutrition and the Pleasure of Eating; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveer, P. Global Governance of Food Production and Consumption: Issues and Challenges; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Micheletti, M. Political Virtue and Shopping: Individuals, Consumerism and Collective Action; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- While for some the term “consumerism” might be associated primarily with a discussion on the negative side effects of consumption and consumption culture, we follow Micheletti here in using the term political consumerism in the more general meaning of ethical or political consumption. So the organized buying of eco-labelled products in supermarkets is regarded as a form of political consumerism.

- Barnett, C.; Cloke, P.; Clarke, N.; Malpass, A. Consuming Ethics: Articulating the Subjects and Spaces of Ethical. Antipode 2005, 37, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Opal, C. Fair Trade: Market-Driven Ethical Consumption; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Consumption, Ecology and Fair Trade; Zaccaï, E. (Ed.) Routledge: London, UK, 2007.

- Spaargaren, G.; Van Koppen, C.S.A. Provider Strategies and the Greening of Consumption. In Globalizing Lifestyles, Consumerism, and Environmental Concern—The Case of the New Middle Classes; Lange, H., Meier, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- In some European countries, ENGOs mobilized citizen-consumers to participate in developing an assessment tool for mapping out the green performance of food-retailers. Volunteers counted the number of eco- and fair-trade products on the shelves of their local retail outlets. The results were made available by the national ENGOs on the internet to be used by consumers interested to know more about the green performance of the supermarkets in their neighborhood. Best performers were rewarded with the prize for “green retailer of the year”. (Korbee, D. Greening Food Provisioning: Sustainability Strategies of Dutch Supermarkets as Communicated through the Physical Characteristics of the Retail-outlets . Master Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]).

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Thinking Sociologically; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, R. Structuration Theory; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Van Raaij, W.F.; Verhallen, T.M.M. A behavioural model of residential energy use. J. Econ. Psych. 1983, 3, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H.; Van Knippenberg, A.; Van Knippenberg, C. Attitude versus general habit: Antecedents of travel mode choice. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 24, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, J. Mobility in Transition: A Practice Approach to the Study of Sustainable Mobility(Preliminary Title); Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, (expected in 2011).

- Thøgerson, J. Spillover Processes in the Development of a Sustainable Consumption Pattern. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgerson, J.; Olander, F. Spillover of Environment-Friendly Consumer Behavior. In Proceedings of the 5th Nordic Environmental Research Conference, Aarhus, Denmark, 14–16 June 2001.

- Next to the EU-funded international project DOMUS (UK, Sweden, The Netherlands; 2000–2004) and the national projects RESOLVE (UK, Surrey, 2004–present), CONTRAST (The Netherlands, 2005–2009) there are a number of smaller projects in Germany (Hamburg University), France (INRA), UK (Lancaster), Denmark (Copenhagen) and Norway (SIFO) organized with the help of theories of practices.

- Sassatelli, R. Consumer Culture: History, Theory and Politics; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. Practice and Field: Revising Bourdieusian Concepts; CRIC Discussion Paper No 65; Centre for Research on Innovation and Competition (CRIC): Manchester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. Consumption and Theories of Practice. J. Consum. Cult. 2005, 5, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. The Ecological Modernization of Production and Consumption. Essays in Environmental Sociology . Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren, G. Sustainable Consumption: A Theoretical and Environmental Policy Perspective. Soc. Nar. Resour. 2003, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Warde, A. Inconspicious Consumption: the Sociology of Consumption, Lifestyles, and the Environment. In Sociological Theory and the Environment: Classical Foundations, Contemporary Insights; Dunlap, R., Buttel, F., Dickens, P., Gijswijt, G., Eds.; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2002; pp. 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E. Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, B; Chappells, H.; Shove, E. Infrastructures of Consumption: Environmental Innovation in the Utility Industries; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gram-Hanssen, K. Practice Theory and the Question of the Green Energy Consumer. In Proceedings of the ESA-Conference, Glasgow, UK, 3–6 September 2007.

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions and System Innovation: A Co-Evolutionary and Socio-Technical Analysis; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 99–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R. Technology and the transition to environmental sustainability. Futures 1994, 26, 1023–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Marvin, S. Splintering Urbanism; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Infrastructure in Transition: Networks, Buildings and Plans; Guy, S.; Marvin, S.; Moss, T. (Eds.) Earthscan: London, UK, 2001.

- Urry, J. Sociology beyond Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Mobilities; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P.J.; Spaargaren, G. From Additions and Withdrawals to Environmental Flows: Reframing Debates in the Environmental Social Sciences. Organ. Environ. 2005, 18, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governing Environmental Flows: Global Challenges to Social Theory; Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J.; Buttel, F.H. The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social—An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens’ reservations with respect to studies emphasizing the huge impact of technology for social change derive from his hesitation to embrace “industrial society-theories” as formulated for example by Daniel Bell or Alvin Toffler and within environmental social sciences by Joseph Huber amongst others. Industrial society theories overemphasize “internal dynamics of change” within social systems without recognizing the complex interdependencies at the level of the world-system. They share with evolutionary theories a tendency to explain social change referring to only one key-or guiding principle, resulting in teleological explanations of change [12].

- Schatzki, T.R. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki, T.R. The Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change; The Pennsylvania State University Press: Sharon, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A development in Culturalist Theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theor. 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckwitz, A. The status of the “material” in theories of culture. From “social structure” to “artefacts”. J. Theor. Soc. Behav. 2002, 32, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzki distinguishes four kinds of relationships: Causal, spatial, intentional and “prefigurational”, the final form referring to relations between components in the present that particularly enable or constrain some future activities [9].

- Shove, E. Efficiency and Consumption: Technology and Practice. In The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Consumption; Jackson, T., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- While Shove takes up the confrontation with co-evolutionairy theories and transition-theory from an everyday life perspective, she mainly uses empirical examples to illustrate some of their theoretical shortcomings. At the conceptual level, she offers a set of metaphors and schemes for analyzing the technology dependency of social practices which tend to emphasize the determining and lock-in effects of technology in everyday life [57] (Shove, E.; Walker, G. CAUTION! Transitions ahead: Politics, practice and sustainable transition management. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar]).

- The Role of Citizen-consumers in Transitions within Consumption Domains Food Home Maintenance and Mobility; Theory, Method and Policy. Available online: http://www.ksinetwork.nl/downs/projects/II.6.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2010).

- Urry, J. Global Complexities; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P.J. Greening Global Consumption: Politics and Authority. Global Environ. Change 2008, 18, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warde, A. Production, consumption and social change: Reservations regarding Peter Saunders sociology of Consumption. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1990, 14, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warde, A. Notes on the Relationship between Production and Consumption. In Consumption and Class,Divisions and Change; Burrows, R., Marsh, C., Eds.; MacMillan: London, UK, 1992; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- It is important to note that we are dealing here with a specific application of the general ideal-types as developed in the first section of the article. We are discussing here the specific roles of agents in the processes of innovation in the situated consumption practices and routines of everyday life. For example the use of ecological citizenship roles is not confined to just situated consumption practices but can be applied as well to citizen-participation in broader political processes of decision making, also with respect to (sustainable) consumption.

- Van Vliet, B.J.M. Greening the Grid . Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveer, P.; Guivant, J.; Spaargaren, G. Shopping for green food in globalizing supermarkets: Sustainability at the consumption junction. In Sage Handbook on Environment and Society; Pretty, J., Ball, A., Benton, T., Guivant, J., Lee, D., Orr, D., Pfeffer, M., Ward, H., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 411–428. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, M.; Klintman, M. Eco-standards, Product Labeling and Green Consumerism; Palgrave MacMillan: Hampshire, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- While the (re)localization of production and consumption represents a strategy for environmental change which is deeply engrained in environmental social movements and activism, we would argue that “localism” in itself does not represent a viable route to sustainable development. Localization has to be combined with globalization in order to prevent nationalism and protectionism and the reproduction of social inequalities at the global level. We think the recent success of the Fairtrade model of change illustrates the fact that forms of moral authority can also be applied at the interface of the global and the local. See [81].

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an Open Access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Spaargaren, G.; Oosterveer, P. Citizen-Consumers as Agents of Change in Globalizing Modernity: The Case of Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1887-1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071887

Spaargaren G, Oosterveer P. Citizen-Consumers as Agents of Change in Globalizing Modernity: The Case of Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability. 2010; 2(7):1887-1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071887

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpaargaren, Gert, and Peter Oosterveer. 2010. "Citizen-Consumers as Agents of Change in Globalizing Modernity: The Case of Sustainable Consumption" Sustainability 2, no. 7: 1887-1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071887