1. Introduction

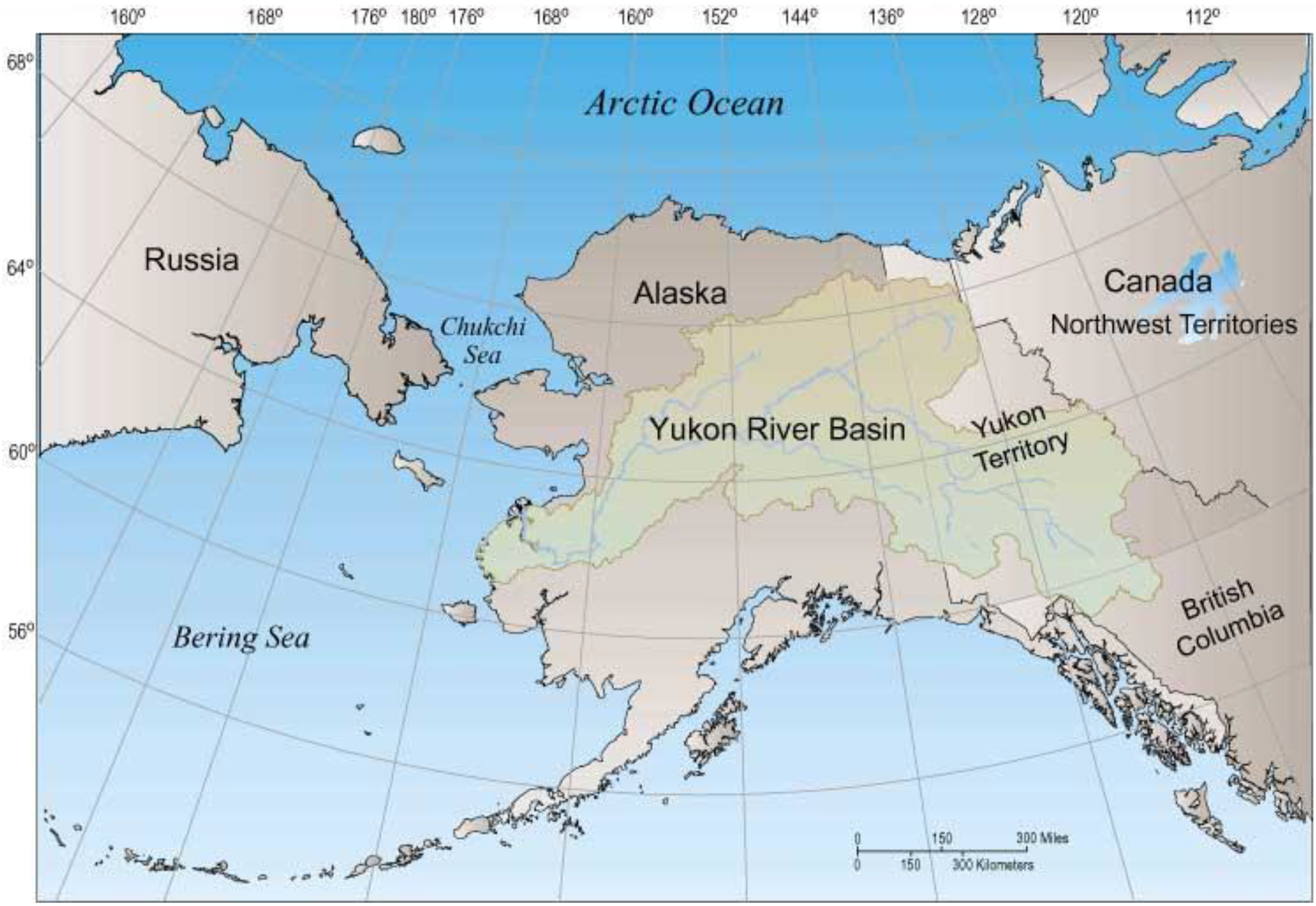

The Yukon River Basin is a defining geographic, ecological, and cultural feature of northwest North America, covering the much of Canada’s Yukon Territory and an enormous band of land across the middle of Alaska before it reaches the Bering Sea (

Figure 1). The Yukon’s drainage encompasses over 850,000 km

2, and includes dozens of tributaries and distributaries, including the Porcupine, Tanana, Koyukuk, and Chandalar Rivers, with about 50 rural and urban communities scattered up and down the river. An intimate and long-standing relationship exists between the “Great River” as it is called in the native Gwich’in Athabascan language, and the Athabascan, Inupiaq, Yupik, and Euroamerican people of these communities. In many ways salmon are at the center of this relationship, playing an important role in the food and economic security of rural and urban Alaskans alike. As with the salmon elsewhere in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, Yukon River salmon are valued not only in economic terms but are also important cultural icons, and their stewardship is a matter that evokes broad public emotion and mobilizes significant political will.

As of late, Yukon River salmon management has attracted much debate and visibility within state, national, and international politics and medias. In 2009, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) enacted numerous subsistence and commercial fishing closures on the river, based on a concern that minimum conservation goals for Chinook (king) and chum salmon would not be met. Ultimately, the internationally agreed-upon conservation goals were not only met but exceeded, and the year was considered by many managers to be an important success following multiple years of escapement shortfalls. However, the lack of a commercial fishery and reduced subsistence fisheries proved disastrous for many rural communities. Smokehouses throughout Alaska were uncharacteristically empty, especially in the middle and upper reaches of the river, and many families were left coping with little prospect for food security for the coming winter of 2009 and 2010. The potential impacts of the closures of the commercial segment of the Yukon Chinook fishery were considered so severe that Alaska Governor Sean Parnell successfully petitioned the federal government to declare a fisheries disaster for the region [

1].

Is it possible to reconcile the perceptions of stock conservation and harvest management success on the one hand with perceptions of disaster and the realities of food insecurity on the other? This paper looks to the 2009 case and these two seemingly incongruous perceptions of the Yukon River system as an opportunity for learning. We explore a complex interplay between what appear to be competing goals of food security and natural resource conservation, focusing primarily on Chinook salmon management but linking this through a discussion of impacts to the management of other non-anadromous fish and terrestrial species. We report on numerous interviews held with residents of various rural communities along the Yukon as well as state and non-profit agency representatives with a role or stake in the management process. Questions regarding impacts on salmon from changes in climate and habitat, and the efficacy and appropriateness of single-species management models are addressed.

Managers and policymakers arguably go to great lengths to reconcile competing uses of Yukon River salmon—commercial, subsistence, and conservation goals—but while managers strive to be adaptive and flexible in their approach to balancing conservation and community needs, the cost of this adaptive process may be too high, both for Yukon River Basin ecosystems and for the people who live there. Is it too much to ask of the Yukon River to sustainably support commercial and subsistence fisheries down-river, up-river, and off shore, for the US and for Canada? Or, is it perhaps too much to ask of regulatory agencies and managers, who must make precise in-season projections in what is an inordinately complex and constantly changing system? We tease apart the various management mandates, challenges, and approaches to find answers to these questions. The insights we draw, though regionally-scaled, have great importance for how we define and address conservation, sustainability, and food security goals at pan-Arctic and global scales.

Figure 1.

The Yukon River Basin. Map courtesy of the US Geological Survey [

2].

Figure 1.

The Yukon River Basin. Map courtesy of the US Geological Survey [

2].

2. Background and Methods

Food security is both an Alaskan and pan-Arctic challenge [

3,

4,

5,

6]. We define food security as having access to sufficient, safe, healthful, and culturally preferred foods; food security is both a condition and a constantly-unfolding process, one through which people try to align short-term needs and long-term goals of health and sustainability. “Country foods”—including sea mammals, ungulates, fresh and saltwater fish, waterfowl, formal and informal gardens, berries, and other botanical resources—provide an important component of food security for many Alaskans. However, as with elsewhere in the North, numerous circumstances and drivers of change limit the ability of rural and urban Alaskans to reliably procure country foods, including vulnerabilities to regional environmental and climatic change [

7,

8,

9], external market shifts in the price or availability of imported fuel and supplies [

10,

11], environmental contamination [

12,

13], and land use changes such as oil, natural gas and minerals development [

14,

15].

As a result, both rural and urban communities in Alaska are heavily dependent on the global food system, which exposes Alaskans to numerous vulnerabilities, including spikes in food and fuel prices and/or disruptions in supply [

16]. Communities in rural Alaska are rarely connected to urban supply centers by road, so the logistics of food and other supplies regularly involve high freight costs of barges and small aircraft. According to the USDA’s 2008 report on household food security in the United States, roughly 11.6 percent of Alaskan households are food insecure, meaning that at some time during the year they had difficulty providing enough food for all members of their household [

17]. This measure, which is near the U.S. Average of 12.2 percent but still among the highest rates in the nation, arguably captures only a portion of those in Alaska coping with food insecurity, and little data is available for food insecurity in rural communities [

10]. Other indicators of food insecurity and food system failure avail, however, especially for rural areas in the state, including trends for various diet- and lifestyle-related disease or syndrome including type 2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, alcoholism, and depression [

18,

19,

20].

Methods

In response to early reports from managers, local fishers, and our own field observations that the 2009 Chinook salmon run would be poor [

21], we engaged in a series of one-on-one informal interviews with a variety of different participants in the Yukon River salmon fisheries to document local observations and reactions, with a focus on the impacts of fishing closures on food security. Semi-structured interviews were conducted from mid-summer through fall of 2009 with 25 residents of several down-river and up-river communities (

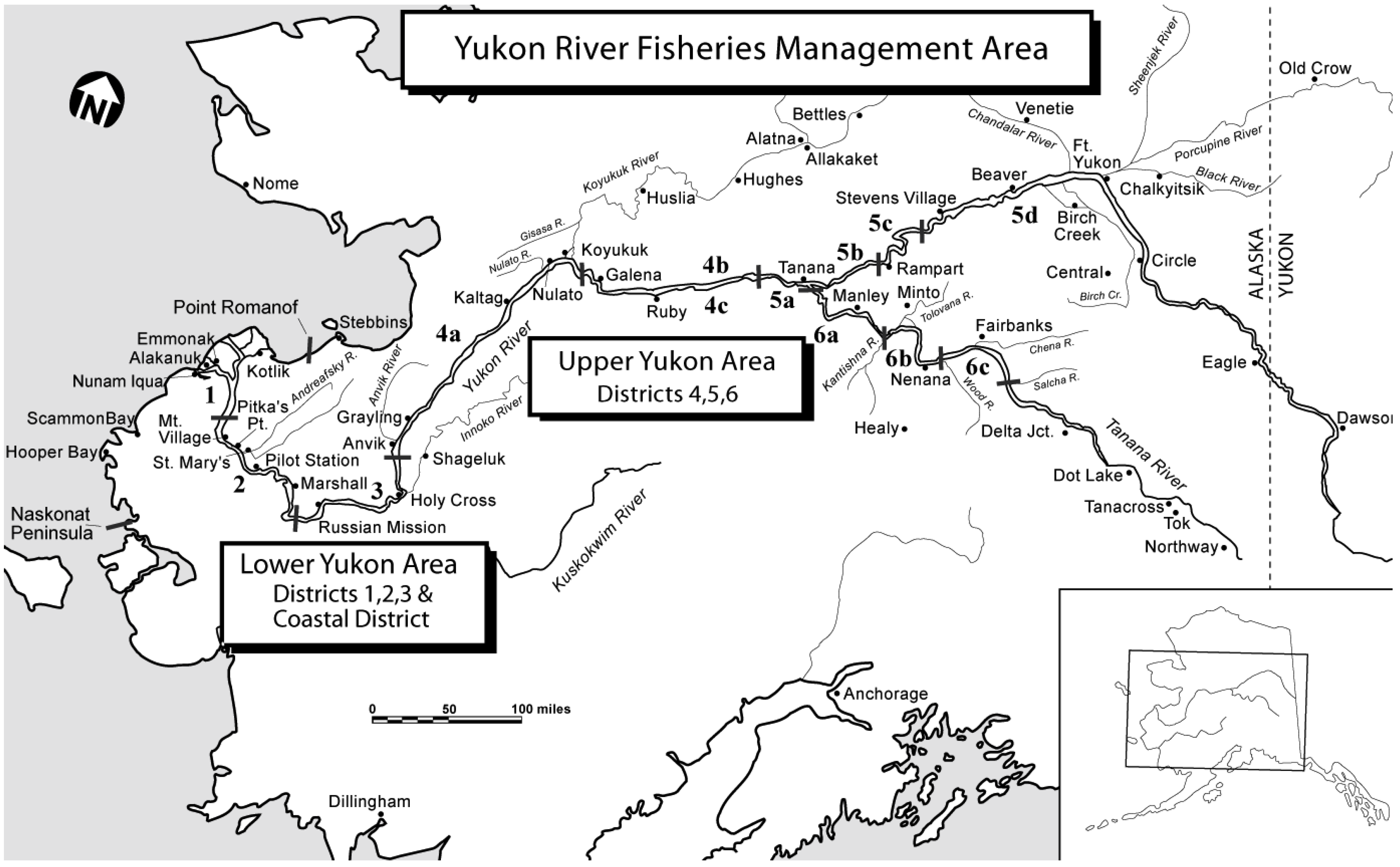

Figure 2): by phone with five residents of Marshall and Emmonak (both down-river communities), and in person with 20 additional people from Beaver, Tanana, Chalkyitsik, and Fort Yukon (up-river). Participants were selected primarily based on availability (as this is a very active time of year for hunters and fishers), and also by previous acquaintance and recommendation from community and tribal leaders for their familiarity with the Yukon system. Interviewees were mostly men ranging in age from 40 to 90 years, which is representative of the overall active fishing population. Topics addressed in the interviews included personal observations of the status of the salmon fishery (e.g., run strength, abundance, long-term changes), as well as the impacts of the 2009 closure on personal and community livelihoods. Interview materials were analyzed using a basic concept-sorting approach [

22].

Subsequent to community interviews, extensive interviews were also conducted with representatives of ADF&G Commercial Fisheries and Subsistence divisions, particularly to establish background and to fact-check details regarding their management approach and the specific management actions taken in 2009. We also interviewed representatives of non-profit organizations such as the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association (YRDFA), Pacific Environment (PE), and the Council of Athabascan Tribal Governments (CATG). Details from this second set of interviews, where included below, are referenced as “personal communications.”

In addition to interviews, we compiled historical data from reports provided by ADF&G and the US-Canada Joint Technical Committee (JTC): for Chinook salmon populations, including annual recruitment, escapement, and brood tables, and for Chinook use by community and for commercial and subsistence purposes in the US and Canada. Calculations and graphs were produced using OpenOffice.org software (Sun Microsystems, Santa Clara, CA).

Figure 2.

Major Tributaries and Communities of the Yukon River Basin. This map also shows how the river is divided into management units, a topic discussed in more detail later in the paper. Map courtesy of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game [

23].

Figure 2.

Major Tributaries and Communities of the Yukon River Basin. This map also shows how the river is divided into management units, a topic discussed in more detail later in the paper. Map courtesy of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game [

23].

3. Yukon River Salmon Governance and Management

The Yukon River is the largest salmon-bearing river in Alaska, with about 50 remote rural communities along its long path from the Bering Sea to Canada. As mentioned above, Yukon River salmon play an important role in the food security of many Alaskans. Though roughly 98% of the fish harvested in and off the coast of Alaska go to consumers outside the state, 90% of Alaska’s rural population, which represents 20% of the state’s total population and 49% of the Alaska Native population, rely on locally procured fish for at least part of the year [

24]. Salmon are easily the most ubiquitous food-fish in Alaska, an important cultural and nutritional keystone species and the primary source of protein in many rural communities for much of the year [

25,

26]. Salmon are easily stored, either frozen or dried, smoked, and then often canned in oil. Salmon are also an important source of commercial income for many rural communities, especially in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, where the money made on the commercial salmon catch often represents a fisher’s entire annual salary [

27]. On the market, these wild fish fetch a high price as a regionally-branded, luxury food item that is high in nutrition and widely perceived to be sustainably-managed [

28,

29].

Salmon subspecies in the Yukon include an annual run of Chinook (a.k.a. king) (

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) salmon, a summer and fall chum (

O. keta) salmon, and a smaller but important coho (

O. kisutch) salmon run. Salmon are an “anadromous” fish species, which describes a life-cycle in which fish hatch and rear in freshwater (1–2 years), spend a portion of their lives maturing in the ocean (3+ years), and ultimately return to fresh water to spawn and die. The spatial extent and complexity of salmon habitat and life-cycle introduces numerous points of vulnerability, whether to disruptions to riverine habitat (e.g., dams) or predation or any possible mortality while at sea [

30]. As a result, management for both conservation and a sustained yield presents significant challenges for traditional “single-species” management approaches [

31].

The Yukon River salmon fisheries fall within the international jurisdiction of the Pacific Salmon Treaty (PST), signed by the US and Canada in 1985. The primary mandate of the PST—which covers salmon stocks in Alaska as well as in Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Yukon Territory and British Columbia—is conservation, via both the elimination of overfishing and the restoration of degraded salmon populations [

32]. The PST establishes baseline limits to the number of salmon that can be harvested from each stock, which are revised year to year by managers who take into account existing data on annual variations in abundance of salmon stocks and the desire to reduce interceptions and avoid undue disruption to existing fisheries. Most of the stipulations of the PST deal with ocean fisheries where salmon are intercepted hundreds of miles from their river of origin; trans-boundary river scenarios like the Yukon are noted, but the PST does not, however, specifically address Yukon River stocks, other than through the creation of the Joint Technical Committee (JTC) directed to compile information on the Yukon fishery, and to oversee area research needs [

33].

The establishment of a permanent, codified agreement for the Yukon came in 2001, following a devastatingly poor Chinook run in 2000. The Yukon River Salmon Agreement (YRA) establishes an international commitment to conservation, restoration, and sustainable harvest of Yukon River salmon. Both countries agreed to manage their salmon fisheries to ensure that enough spawning salmon are available to meet minimum sustainable escapement (MSE) requirements and to provide for harvests, when possible, according to specific harvest sharing arrangements. Escapement is the term for the portion of returning salmon that avoids harvest (escapes) and presumably reaches spawning grounds. The MSE is thus the minimum number of spawners thought necessary to maintain the population.

Some guidelines for setting the MSE are laid out in the YRA, but specific goals are determined by the JTC through an adaptive management process, one that is refined each year based on historical data for escapement and recruitment (those fish that return to spawn from a particular parentage year, or that year’s reproductive potential) as well as from in-season monitoring (J. Hilsinger, ADF&G, pers. comm. 2009). The targets for escapement are based on an estimate that 50% of Yukon River salmon are bound for spawning grounds in Canada [

30]. Both countries share the obligation to meet these annually-set minimum escapement objectives, and have agreed to limit or even close fisheries outright to protect spawning escapement in years of low runs.

In Alaska, ADF&G is in the difficult position of having to meet not only the primary mandate of conservation but also of having to attend to the hugely important subsistence and commercial fisheries each year. The state constitutional mandate for ADF&G is not just the conservation of resources, but their enhancement for use by Alaskans. Thus, escapement objectives are set to not just maintain a viable salmon population but also to maximize and ensure a surplus of recruits above MSE, thus allowing sustainable harvests by subsistence and commercial fisheries in the US and Canada (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Ricker Curve. Displays a hypothesized relationship between the number of spawners and the recruits from that parentage. Recruits represent the reproductive potential of returning adults. The curve illustrates the surplus production of salmon, where more than sufficient progeny are produced to replace parentage; it has two features that conform to available observations about salmon reproduction: it can have a dome to the left of the replacement point, and there is always some recruitment from any finite level of spawning. The area above replacement represents the maximum sustainable yield (MSY).

Figure 3.

The Ricker Curve. Displays a hypothesized relationship between the number of spawners and the recruits from that parentage. Recruits represent the reproductive potential of returning adults. The curve illustrates the surplus production of salmon, where more than sufficient progeny are produced to replace parentage; it has two features that conform to available observations about salmon reproduction: it can have a dome to the left of the replacement point, and there is always some recruitment from any finite level of spawning. The area above replacement represents the maximum sustainable yield (MSY).

Recent Management History and the “Success” of 2009

Each year projections and pre-season management plans for salmon are made by ADF&G and the JTC, but these are frequently revised through in-season actions. In-season decisions are then made for how to structure fishing windows, through emergency subsistence closures and commercial openings. By default, subsistence fishing is open on the river, and is closed by “emergency” order; commercial fisheries are by default closed, and must likewise be opened. These decisions need often need to be made, however, before the fish have passed that part of the river in question. Managers use both forecasts and models for the strength and timing of salmon runs as well as in-season monitoring in order to make these decisions. The primary monitoring locations including Pilot Station (sonar) at the mouth of the river for assessing run strength, various test fishery to gauge abundance, and finally another sonar station at Eagle just before the Canadian border [

34]. Trigger points are identified that when reached prompt actions (

i.e., closures on subsistence fisheries or openings for commercial fisheries) in the various Yukon River management areas (see again

Figure 2).

The difficulties inherent to in-season escapement-based management are many. The Yukon is a turbid river, which makes fish counting difficult. The great length of the Yukon also means that there is considerable potential for mortality between Pilot Station near the mouth and the up-river community of Eagle; this much distance also means that results from actions taken down-river, and their impacts up-river may not be realized for up to a month [

35]. If returns appear to start strong but then taper down quickly, there is a chance that the harvest allowed down-river may be in excess of the number actually available above MSE [

36]. As fishing openings and closures are scheduled using projections regarding run timing and speed, there are also chances for openings to be misaligned with when the salmon actually pass by the waiting communities [

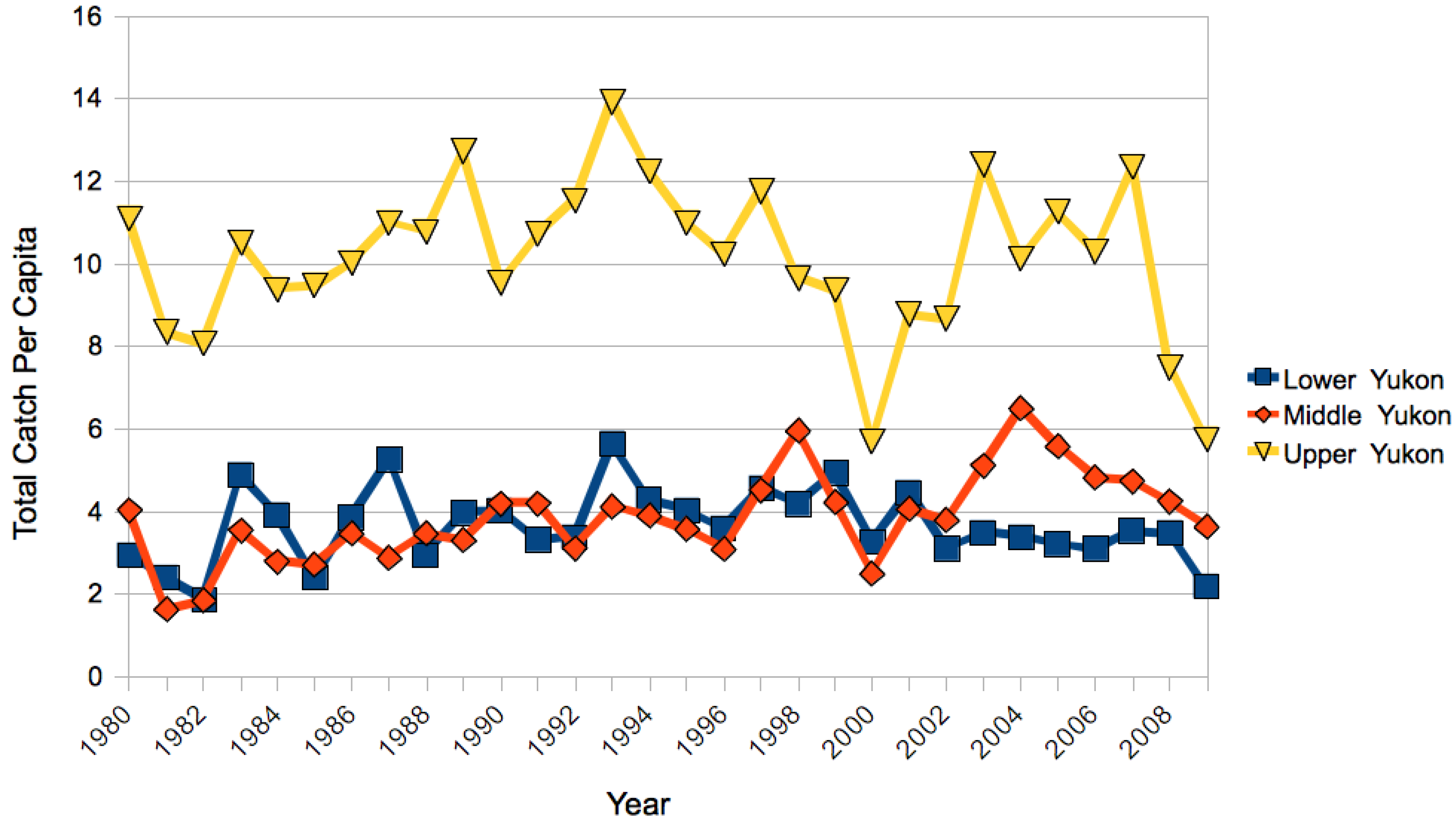

36]. As we discuss later, there is significant political and public pressure on ADF&G to meet these multiple and sometimes competing goals. Nevertheless, uncertainties in the present approach to monitoring and decision-making create vulnerabilities for the communities that rely on Chinook salmon, vulnerabilities that are differentially distributed between rural communities and often hardest on the Alaskan communities furthest up-river.

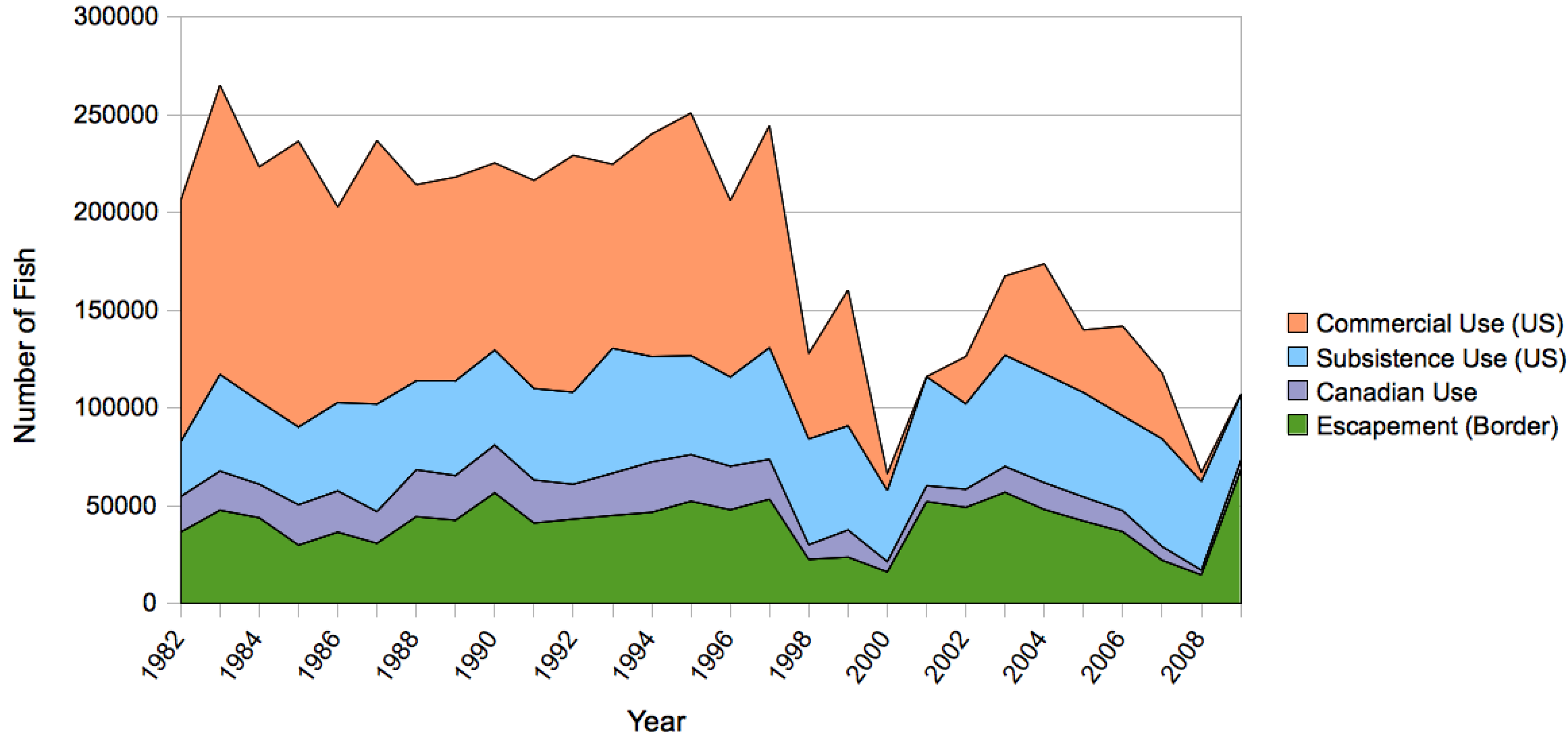

Three very poor Chinook runs occurred on the Yukon beginning in 1998 (

Figure 4). In combination these mobilized new and urgent management actions because up to that point the Chinook runs on the river had been relatively stable [

37]. In 2001, ADF&G responded by significantly limiting commercial harvest openings, and implementing closures to shorten subsistence fishing windows from 7 days to 24–48 hours. There were a number of years following these changes, 2001–2006, where runs, though not as large as seen in the 1980s or 1990s, met both MSE and subsistence needs. Poor runs resumed in 2007, however, and a particular concern was raised regarding the health of the Canadian stock; whereas Canadian spawners were considered to contribute roughly 50% of the Yukon Chinook run, genetic testing showed the Canadian contribution had fallen as low as 35–37% [

34]. In 2007 and 2008 MSE goals were not met, though both subsistence and commercial fisheries were allowed in 2007; in 2008, ADF&G managers tried to accommodate the 2007 data and this new concern for Canadian stocks through complete closures of the commercial fishery, but MSE was still not achieved.

Thus, there were significant pressures in 2009 for ADF&G to turn Chinook management around [

38], and by the terms set out in the PST and YRA, management of Chinook salmon in 2009 was indeed a great success. The MSE target was 48,000 fish, and post-season numbers show total escapement in the neighborhood of 70,000 fish [

39], a significant increase over the especially low escapement the year prior, and making 2009 the first year since 2005 to meet the MSE goal and possibly the highest escapement on record. The secondary goal of the YRA, equitable harvest sharing between the US and Canada, was also met in 2009, with harvest openings occurring for both countries and total catches falling near a 75%–25% US-CAN split [

39].

Figure 4.

Relative Proportion of Chinook Use, 1982–2008. Fish use is stacked here for comparison, meaning that the zero point for each segment begins at the top of the previous segment. Note that “commercial use” includes only salmon caught along the river, and not salmon caught in ocean fisheries. Note that the prioritization of subsistence fisheries over commercial fisheries in the US appears to be effectively implemented, with the relative proportion of subsistence use remaining more or less stable, while commercial use varies more greatly and follows MSE, especially since 1997. Also note the large commercial fisheries that were allowed in 1998 and 99, despite the low escapement. Data from [

21,

23,

39,

40].

Figure 4.

Relative Proportion of Chinook Use, 1982–2008. Fish use is stacked here for comparison, meaning that the zero point for each segment begins at the top of the previous segment. Note that “commercial use” includes only salmon caught along the river, and not salmon caught in ocean fisheries. Note that the prioritization of subsistence fisheries over commercial fisheries in the US appears to be effectively implemented, with the relative proportion of subsistence use remaining more or less stable, while commercial use varies more greatly and follows MSE, especially since 1997. Also note the large commercial fisheries that were allowed in 1998 and 99, despite the low escapement. Data from [

21,

23,

39,

40].

5. Discussion: Management Challenges, Variables, Unknowns

By the end of the 2009 season, over 70,000 fish had escaped to spawning grounds in Canada. Critics of the management actions taken by ADF&G point to this as evidence that actions were overly conservative and came at the expense of the food security of rural communities; the 12,000 fish surplus, they argue, though only a fraction of the total subsistence harvest during a good year, would still have fed many families. Representatives of ADF&G, however, argue that a margin of 12,000 fish is well below the possible precision of the present management approach [

35]. In other words, managers feel that there is simply too much uncertainty inherent to the Yukon system to have managed the stock with any more precision, and it is better to have erred on the side of conservation than to have allowed a fishery and once again fallen short of meeting conservation goals and treaty obligations to Canada.

The effectiveness of salmon management is commonly measured only by whether or not spawning escapement objectives are met [

30,

33]. However, as described above, escapement as a management tool is at best imprecise, and its effectiveness is contingent on managers’ ability to efficiently estimate run size, preferably in-season, and on the presence of well developed monitoring programs in all fisheries. These competencies are crucial because of fundamental, often habitat-driven uncertainties regarding the escapement-recruitment relationship for any salmon population. In practice, observing anything close to the ideal relationship depicted in

Figure 3 is uncommon, even in cases where there are decades of reasonably high-quality monitoring data ([

30], p. 278). ADF&G representatives note their frustration with how frequently escapement years considered “strong” beget poor runs, and vice versa [

34,

35,

37]. As we discuss below, there are numerous variables and uncertainties that likely contribute to the apparent lack of consistency in between escapement and recruitment of Chinook on the Yukon, including biophysical challenges resulting from climate change, and especially changes to the location of spawning grounds.

5.1. Climatic Change

The ecosystems of Alaska are experiencing some of the most pronounced impacts of climate change on Earth, and in this the Yukon River Basin is no exception [

46,

47]. In high latitudes, lakes, rivers, and wetlands are not connected with groundwater in the same way that they are in temperate regions, as permafrost—a solid layer of earth beneath the top layers of soil that remains frozen year-round—can reach downward 10–20 meters in Interior Alaska and Yukon. With climate change this permafrost is thawing [

48], and when combined with abrupt or extreme events like storms, flooding, and coastal erosion, the hydrology of the Yukon River Basin and Delta are being transformed [

49,

50,

51,

52]: locals and scientific researchers have both reported changes such as the gradual drying of wetlands, dramatic permafrost-thaw landslides that can block entire channels, and in some cases the rapid draining of entire lakes.

Inter-annual variability as reflected in both instrumental records and local observations is considerable, however [

53,

54]; seasonality is unpredictable and changing, and river ice thickness and the timing of break-up and freeze-up are different from year to year. This makes it difficult for local people to plan their subsistence activities effectively as they did in the past, and it creates problems for managers too. In 2010, to mention but one example, an ice jam at the mouth of the lower Yukon caused a delay in when fish could enter the river. When the first fish finally arrived as far up as Fort Yukon in late July, the Yukon was in flood, reported to be “higher than anyone had seen in years or could remember,” and quantity and size of driftwood coming down made it impossible to fish. A few people put wheels and nets in on July 15, one or two fish were caught, then all had to be pulled the same day as high water and drift made it impossible to fish. High water and excessive debris continued well through August and into early September. In this case it is ecology and weather, not management, that is contributing to food system vulnerability and a “perfect storm” for another food security problem in 2010, at least until river conditions improve, and assuming too that fish numbers are sufficient for managers to meet escapement goals and keep the subsistence fishery open up-river.

Other ongoing changes to the Yukon and its tributaries include rising water temperatures as well as a longer ice-free period [

51,

55,

56]. It remains unclear as to what the impacts on salmon of warmer water temperatures will be; however, as individual salmon runs are often highly adapted to their particular ecological and climatological conditions, numerous possible negative impacts have been hypothesized [

57]. One possibility is that warmer spawning and incubation waters will prompt young fish to migrate to the ocean too early, when marine food resources are still low. Rising water temperatures are also a potential driver for increases in the prevalence of salmon parasites such as

Henneguya salminicola [

58]. River ice dynamics are also changing; the Yukon also freezes seasonally, which is an important feature both for the people who travel along the river in winter, as well as for understanding the year-to-year changes to the river and riverbed that erosion from the often-dramatic spring break-ups can cause [

59].

In the ocean, climatic changes are also anticipated to impact salmon runs in unpredictable ways, including possible inundation of low-level spawning areas by storm surges and rising sea-levels [

57]. Increases in the severity or frequency of storms may also drive the mixing of ocean salmon with pollock and other fish, potentially adding to the by-catch problem. Despite uncertainty about these possible impacts, there is consensus that stewardship plans for Yukon River salmon can no longer afford to hold ecological conditions constant [

59,

60].

5.2. Where Are the Fish Spawning?

As noted, the YRA is structured around an estimate that 50% of Yukon River Chinook spawn after passing into Canada via the main-stem of the river. This 50% figure, which is monitored primarily through the use of genetic identification [

61], is a lynch-pin in the entire Chinook management approach. However, while commercial fisheries managers have observed changes to chum salmon spawning location [

61], they are confident that the makeup of the Chinook stock remains constant. While genetic testing has proven invaluable in a variety of contexts for salmon and other conservation concerns, there are questions about whether genetic testing is a tool capable of picking up fast changes in the geography of spawning for Yukon sub-populations. There is a clear distinction between down-river and up-river Chinook, so up-river salmon were to begin spawning in lower-Yukon habitat this would likely be quickly identified with genetic testing [

62]; however, whether and how quickly changes to spawning in up-river areas would be reflected with genetics depends on the locations of yearly genetic sampling and the composition (

i.e., homogeneity) of the stocks tested [

62]. In the context of rapid change, the latter can only be assumed. Moreover, genetic monitoring surely would not be able to

anticipate dramatic in-season changes or disturbances to the river system that could divert spawners to alternate routes.

Thus, the question of where Chinook are spawning is arguably unresolved. If local observations of change are accurate, then it is possible that the current management approach is overemphasizing the role of Canadian stock in the composition of Yukon River salmon. Indeed, if more fish are leaving the main-stem Yukon before the Canadian Border, this would provide an alternate hypothesis for explaining the recently identified decline in the relative proportion of “Canadian” fish. There are hundreds of streams where spawning salmon could depart from the Yukon before it passes through to Canada, and as rivers change, spawning grounds change. Given the myriad ongoing climatic and ecological changes that the Yukon River Basin is experiencing, the need to monitor for how these ecological and hydrological changes are influencing the location of spawning grounds and the composition of the fishery is clear. A vast majority of the Yukon’s terminal spawning streams are especially remote, and the costs and logistics of monitoring these remote portions of the river system are considered to be prohibitive [

34]; but, as we discuss below the cost of not addressing these points of uncertainty may be higher still.

6. Are We Asking Too Much?

As established in international treaty and as implemented by ADF&G, the constitutional and legislative mandate for the management of Yukon River salmon is conservation. In 2009, this appears to have been a goal incompatible with the goal of rural food security. However, conservation in a single-species context is not the same proposition as conservation in an ecosystem context. While we can frame the happenings of 2009 independently in terms of an agency’s success to conserve salmon, or their failure to equitably serve the various stake-holder groups in Alaska, we can also choose to look at 2009 as an indicator for the need to develop a more robust and holistic approach to fish and wildlife management, one in which conservation and food security are not competing but complementary processes.

Despite the best of intentions, efforts throughout the Pacific to manage and conserve salmon for optimum production have more often generated more uncertainty and variability than they have stability [

63]. The salmon life-cycle cuts across the comfortable disciplinary boundaries and environmental categories normally used to distinguish river, estuary, and ocean systems, and requires a management approach that is based on system-wide integration rather than single-species fragmentation. Yukon River salmon are clearly managed in a single-species context, one in which there are no mechanisms or metrics for identifying and responding to impacts across species or between regions, as in the case of the differential distribution of impacts between lower and upper Yukon communities described above. Conversely, an ecosystem-based management approach recognizes the important and diverse ecological roles of fish and other species in the dynamics of ecosystems at multiple scales, and strives to sustain not just the delivery of harvestable resources but also these important ecological processes [

64]. Ecological connectivity, for example, is of great importance to the health of salmon populations [

65], yet contemporary management plans continue to focus on a single species escapement-recruitment model for managing the population in both the short and long term.

Ethnographic, historical, and archaeological research suggest, however, that in order to reverse the downward spiral of so many Pacific salmon populations, greater investment is necessary in activities that fully engage the human dimension of ecosystems in ecosystem-based management, and in ways that foster closer connections among people, fish, and their food sheds [

66,

67,

68]. This is the goal of a food systems approach [

69]. Salmon are the keystone in a complex regional food system, and there are numerous possible pathways that management actions may impact not just human communities but other aspects of the Yukon River Basin ecosystems as well. For instance, the Yukon Flats has a critically low moose (

Alces alces) population. Local experts that we interviewed, however, report observing preliminary signs of recovery in the moose population, including numerous sightings of young cows.

What might the impacts of this and future fishing closures be on what appears to be a slowly recovering moose population? Complementary to salmon, moose also play an important role in local foodways; the ability to rely more heavily on moose during times of shortage of salmon is a key aspect of the adaptive subsistence strategy that has allowed Alaska Natives to live so successfully on the Alaska landscape for so long. Given that the chum salmon fisheries were also closed for the majority of Alaskans in 2009, significant compensatory predation pressure on other resources should be anticipated. According to some of the rural residents we worked with in up-river villages in 2009 and 2010, such prey-switching would likely not be limited to moose, but should be expected to have impacts on other fish and game species, their habitat, and on other food sources such as village stores and backyard gardens.

The challenge of ecosystem-based management is to find a paradigm for integrating knowledge of climate futures and natural environmental variability within a context of place-based drivers of change such as predation and harvest, while still serving regional goals such as single-species conservation and ecosystem and human health. It is essential that the actions taken to conserve salmon do not themselves weaken or degrade the very communities for whom those salmon are purportedly being conserved [

70]. Managing for a flexible and adaptable food system, we argue, is to take an ecosystem-based approach that explicitly includes the human dimensions of the ecosystem, linking specific goals for the health and conservation of individual species to broader goals of human health and community stability [

71,

72,

73]. From a food systems perspective, salmon conservation, moose conservation, habitat conservation, and food security are not just complementary but are highly connected objectives and priorities. Under a food systems approach, internationally-agreed-upon metrics for salmon conservation would not necessarily have to change,

per se, but the system implementing them would need to become more flexible and integrated in design, mimicking the flexibility and interconnectedness of the natural system being managed, so that these multiple goals are pursued together. Too, acknowledging that these species exist within a food system highlights rather than obscures the complex relationships therein, and allows managers to better observe, track, and understand the impacts of a changing climate, a changing landscape, and the changing communities embedded within [

69].

Numerous political and institutional barriers likely exist, however, to the implementation of such a dramatic change. Alaska’s natural resources are arguably some of the most heavily managed and contested in the world [

74,

75]; corporate, state, and federal interests create a cluttered patchwork of competing jurisdictions, mandates, and agendas. At the state level, ADF&G is split into numerous independently-operating divisions which do not necessarily have clearly aligned mandates, philosophies, or practices. At least four divisions of ADF&G are interested in some aspect of the salmon fisheries: Commercial Fisheries, Subsistence, Sport Fish, and indirectly, Wildlife Conservation. PST and YRG protocol are implemented by the Commercial Fisheries division, whose mandate is “to protect, maintain, and improve the fish, shellfish, and aquatic plant resources of the state, consistent with the Sustained Yield Principle, for the maximum benefit of the economy and the people of Alaska” [

76], which potentially could conflict with the conservation-based mandate of the PST. The mission of the Division of Wildlife Conservation is similar—to “conserve and enhance Alaska’s wildlife and habitats and provide for a wide range of public uses and benefits.” The mandate of Wildlife is not directly engaged in salmon management, but their mandate to conserve “habitat” does not include salmon habitat to maintain a source of food for bear conservation, particularly in coastal areas [

77].

Organizational divisions such as these present cognitive and jurisdictional challenges to creating and implementing management policies that are scaled to the ecosystem or watershed or food system rather than to individual species. However, state and federal organizations like ADF&G and the US Fish and Wildlife Service remain arguably in the best position, and in possession of the best resources, to facilitate a complex task like ecosystem-based management [

78]. Everyone involved has a stake in a system that works better, and the managers at ADF&G clearly do everything in their power to meet community needs. The challenge is therefore not only a matter of having the best scientific understanding of the system but also of having the political will to implement the necessary changes to our social and cultural institutions. It often requires a crisis or disaster to set the stage for dramatic changes in governance and management [

79,

80]. Whether or not the events of 2009 will mobilize the political will necessary to instantiate such a regime change in Alaska, however, remains to be seen.

7. Conclusions

By anyone’s reckoning, 2009 was a difficult year on the Yukon, and in a context of a changing climate and rising food and fuel prices, the cumulative long-term effects of these closures on Alaska’s rural communities likely have yet to be realized. While there is some silver lining in the success as measured with the metrics of international treaty, most are understandably unhappy with the final outcomes. The intent of this paper is not to place blame, however, as everyone involved works hard, and share intentions that are both honorable and for the most part congruent. Rather, we detail this case to identify the social and ecological circumstances that set the stage upon which these events played out. If there are lessons that managers and conservationists in Alaska and elsewhere can take from this case, it is that observation and understanding are important, coupled aspects of effective natural resource management, especially in a context of environmental variability and change. But, understanding change and, perhaps more importantly, understanding how humans cope effectively with change, is a more complex process and requires a different mindset and toolkit than is presently available. Without the highest-quality, up-to-date information, even the best understandings of and models for system dynamics are rendered impotent [

81].

More and better science and monitoring can go far to alleviate some of the problems experienced in 2009, although reorienting management around an ecosystem-based approach is clearly the long term need. Focusing on the system as a food system, something more than a food web since it incorporates complex economic, community and individual health, and sociological processes as well, extends that ecosystem approach to the human dimensions of natural resource management, a challenge that many ecosystem-based management regimes have yet to achieve [

67]. It is also crucial that everyone involved recognize the natural uncertainty and variability of the Yukon system. Policymakers need consider new ways to blend these jurisdictions and mandates of the traditionally-secularized worlds of conservation, commerce, and subsistence management, in new and creative ways that mimic the variability and interconnectedness inherent to the Yukon system. We are asking too much of the Yukon River, and for that matter of Yukon River managers, if we ask them to consistently and uniformly provide for both a thriving salmon population and thriving human communities without the support of the rest of Alaska’s landscapes and seascapes. Alaska’s natural resources are a great asset, and if we organize and scale our own social institutions appropriately, they can make our lives easier, not harder.