Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Spatial Plans: A Spanish Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

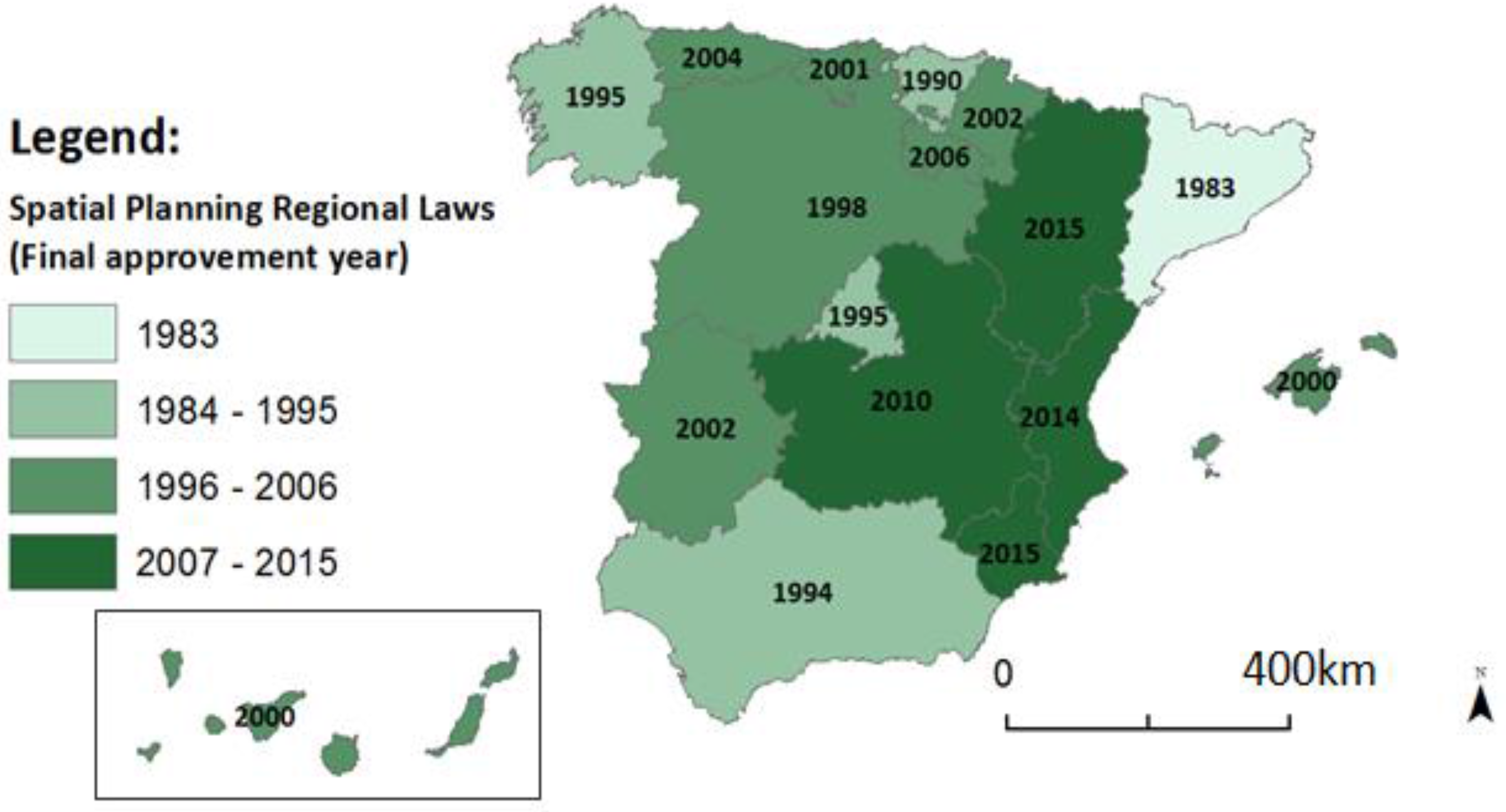

2. Conceptualising Evaluation and Monitoring Framework

3. Spatial Planning in Spain

4. Methodology

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Monitoring Commissions, Reports, and Indicators

5.2. Public Consultation

5.3. Strategic Environmental Assessment for Spatial Plans

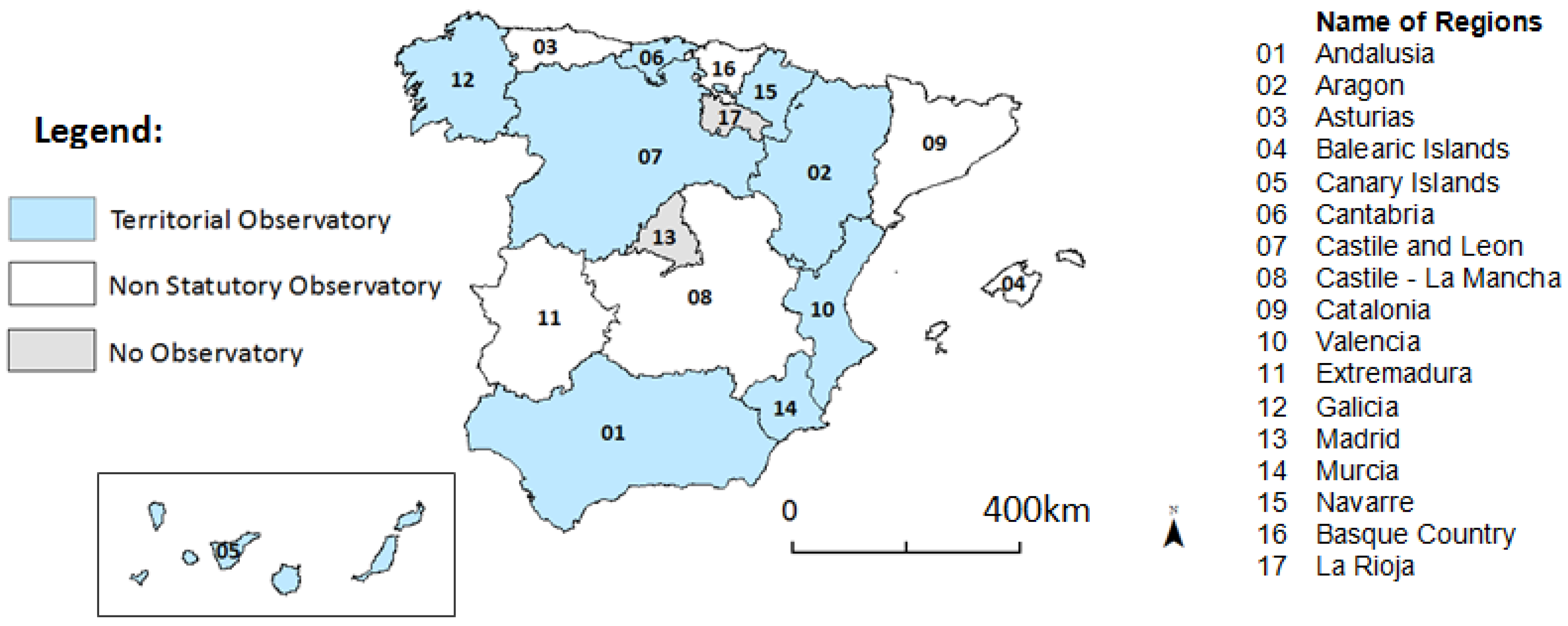

5.4. Territorial Observatories

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Qualitative Interviews: Basic Structured Questionnaire |

|---|

| Were the periodical monitoring reports drafted, as established by the spatial plans basic management mechanisms? |

| How do the spatial planning commissions operate? |

| How are the information systems and the territorial observatories aimed at evaluating spatial planning, operating? |

| Do you have indicators or other formal/informal mechanisms in place to evaluate the plans’ objectives in practice, as required by law? |

| Do the mechanisms or indicators defined in spatial plans involve any kind of responsibility or commitment? By whom? |

| How useful is, in practical terms, the strategic environmental evaluation and monitoring mechanism, established by law in all spatial plans (Directive 2001/42/CE)? |

| Do public participation projects exist for the evaluation, monitoring, and management of plans? What procedure is used or envisaged? |

| What mechanisms are used for inter-administrative coordination and cooperation on this matter? How do they operate? |

| How did the economic crisis affect this? Do budget cuts negatively affect evaluation, monitoring and management of spatial plans? |

| Have other mechanisms for the evaluation, monitoring and management of spatial plans been envisaged? What improvements can be made in this field? |

| Other general considerations or references that the interviewee would like to add: |

Appendix B

| Region | Spatial Planning Laws (Latest Modification or Amended Versions) | Year (Law still Currently in Force) | Provisions for Evaluation, Monitoring, and Review of Spatial Plans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | - Law 1/1994 on Spatial Planning in Andalusia (11/01/1994). (Amended in 2016) | 1994 BOJA * 22-1-1994 | - Criteria for the timeline and drafting of the management report (Art. 7) |

| - Provisions for monitoring and implementation (Art. 7, 11 and 43) | |||

| - District commissions for drafting and monitoring (Art. 8 y 13) | |||

| - Public consultation (2 months) (Art. 8, 13 and 44) | |||

| - Spatial Information System (Art. 33) | |||

| Aragon | - Regional Decree 2/2015 approving the consolidated text of the Law on Spatial Planning in Aragon (17/11/2015). (Amended in 2017) | 2015 BOA * 20-11-2015 | - Spatial management instruments (Art. 5) |

| - Evaluation and monitoring indicators and indexes (Art. 18) | |||

| - Public consultation (2 months) (Art. 19) | |||

| - Environmental evaluation and monitoring procedures (Art.19) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review instruments (Art. 20) | |||

| - Spatial information systems (Art. 55) | |||

| - Spatial indicators system for evaluation and monitoring (Art. 56) | |||

| - Spatial Data Infrastructure (Art. 57) | |||

| Asturia | - Regional Decree 1/2004 approving the consolidated text of the legal provisions on spatial and urban planning (22/04/2004). (Amended in 2010) | 2004 BOPA * 27-4-2004 | - Public consultation (Art. 7) |

| - Principles of inter-administrative cooperation and coordination (Art. 14–16) | |||

| - Provisions for regional and sub-regional guidelines (Art. 31) | |||

| Balearic Islands | - Law 14/2000 on Spatial Planning (21 /12/2000). (Amended in 2012) | 2000 BOIB * 27-12-2000 | - Spatial Policy Coordination Commission (Art. 4) |

| - Public consultation (2 months) (Art. 7 and 10) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review instruments (Art. 7 and 10) | |||

| Canary Islands | - Regional Decree 1/2000 approving the consolidated texts of the Spatial Planning Law and the Natural Sites Law of the Canary Islands (08/05/2017). (Amended in 2015) | 2000 BOC * 15-5-2000 | - Public and citizen participation principles (Art. 4 and 8) |

| - General principles and the duty of administrative cooperation (Art. 4 and 10) | |||

| - Strategic environmental assessment (Art. 16) | |||

| - Public consultation (2 to 4 months) (Art. 20) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review instruments (Art. 20) | |||

| Cantabria | - Regional Law 2/2001 on Spatial Planning and Urban Land Classification systems in Cantabria (25/06/2001). (Amended in 2016) | 2001 BOC * 4-7-2001 | - Duty of inter-administrative collaboration (Art. 8) |

| - Carrying capacity (Art. 12) | |||

| - Definition of information systems (Art. 12) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review instruments (Art. 15 and 16) | |||

| - Public consultation (Art. 16) | |||

| Castile La Mancha | - Regional Decree 1/2010 approving the consolidated text of the Spatial Planning and Urban Development (18/05/2010). (Amended in 2016) | 2010 DOCM * 21-5-2010 | - Duty of inter-administrative coordination (Art. 10 and 11) |

| Castile and Leon | - Law 10/1998 on Spatial Planning in the Castile Leon region (05/12/1998). (Amended in 2014) | 1998 BOCyL * 10-12-1998 | - Social participation (Art. 4) |

| - Environmental report (Art. 11, amended in 2010) | |||

| - Public consultation (45 days) (Art. 12 and 18) | |||

| - Monitoring, review, modification (Art. 13 and 19) | |||

| - Strategic environmental assessment (Art. 17) | |||

| Catalonia | - Law 23/1983 on spatial policies in Catalonia (21/11/1983). (Amended in 2010) | 1983 DOGC * 30-11-1983 | - Spatial Policy Coordination Commission (Art. 8), current Spatial Policy and Urban Development Commission (amended in 2012) |

| - Provisions for modification and review (Art. 15) | |||

| Extremadura | - Law 15/2001 on Land and Spatial Planning in Extremadura (14/12/2001). (Amended in 2015) | 2002 DOE * 3-1-2002 | - Inter-administrative collaboration (Art. 3) |

| - Public participation (Art. 7) | |||

| - Environmental assessment (amended in 2015) | |||

| Galicia | - Law 10/1995) on Spatial Planning in Galicia (23/11/1995. (Amended in 2016)- Law 6/2007 on urgent measures in the field of Spatial Planning and Coastal Management in Galicia (11/05/2007). (Amended in 2016) | 2007 DOG * 16-05-2007 | - Public Hearing and consultation (2 months) (Art. 10 and 15) |

| - Annual control report (Art. 11) | |||

| - Coordinated Action Plans (Art. 18) | |||

| - Environmental assessment (Law 6/2007) | |||

| - Spatial Studies Institute (Art. 31) (Law 6/2007, approved in 2011) | |||

| Madrid | - Law 9/1995 on measures for land, urban and spatial planning in the region of Madrid (28/03/1995). (Amended in 2014) | 1995 BOCM * 11-04-1995 | - Administrative consultation (Art. 6) |

| - Commission for Spatial Concerted Action (Art. 7, derogated in 2010) | |||

| - Public consultation (2 months) (Art. 18) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review (Art. 18) | |||

| Murcia | - Law 13/2015 on spatial and urban planning in the region of Murcia (30/03/2015). | 2015 BORM * 6-4-2015 | - Annual monitoring report on urban development (Art. 11) |

| - Public participation (Art. 12) | |||

| - Spatial Policy Coordination Commission (Art. 15) | |||

| - Administrative coordination (Art. 18) | |||

| - Spatial Reference System (Art. 21 and 37–39) | |||

| - Environmental Assessment (Art. 24, 26 y 69) | |||

| - Public consultation (2 months) (Art. 70) | |||

| - Review, adaptation and modification (Art. 171–174) | |||

| Navarre | - Regional Law 35/2002 on Spatial and Urban Planning in Navarre (20/12/2002). (Amended in 2015) | 2002 BON * 27-12-2002 | - Public participation plan (20 days) (Art. 7) |

| - Spatial Planning Commission (Art. 14) | |||

| - Spatial Policy Social Council (Art. 15) | |||

| - Inter-administrative coordination and cooperation (Art. 17–19) | |||

| - Environmental Assessment (Art. 30) | |||

| - Provisions for compliance: spatial monitoring indicators (Art. 32) | |||

| - Review, modification and updating (Art. 35 y 37) | |||

| Basque Country | - Law 4/1990 on Spatial Planning in the Basque Country (31/05/1990). (Amended in 2003) | 1990 BOPV * 3-7-1990 | - Ensures permanent adaptation of spatial planning instruments (Art. 6) |

| - Public Hearing and consultation (2 months) (Art. 10 y 13) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review of instruments (Art. 10) | |||

| - Coordination body: Spatial Planning Commission for the Basque Country (Art. 28) | |||

| - Participation bodies. Spatial Policy Advisory Council for the Basque Country (Art. 30) | |||

| Rioja | - Law 5/2006 on Spatial and Urban Planning in La Rioja region (02/05/2006). (Amended in 2015) | 2006 BOR * 4-5-2006 | - Inter-administrative coordination (Art. 8) |

| - Public participation (Art. 10) | |||

| - Provisions for compliance: spatial monitoring indicators (3 months) (Art. 20) | |||

| - Environmental assessment (Art. 20) | |||

| - Monitoring reports (every 5 years) (Art. 21) | |||

| - Provisions for the modification and review of instruments (Art. 21) | |||

| Valencia | - Law 5/2014 on Spatial, Urban and Landscape Planning in the Valencia region (25/07/2014). (Amended in 2017) | 2014 DOCV * 31-7-2014 | - Cooperation and coordination: spatial governance schemes (Art. 15 and 16) |

| - Strategies and actions to achieve the objectives (Art. 16) | |||

| - Joint environmental and strategic spatial assessment (Art. 16, 47–56) | |||

| - Public participation (Art. 53) | |||

| - Provisions for modification and review of instruments (Art. 56) |

Appendix C

| Initial Strategic Document and Strategic Environmental Study (Regular Procedure) | Strategic Environmental Document (Simplified Procedure) |

|---|---|

|

|

References

- Council of Europe. European Regional/Spatial Planning Charter. In Proceedings of the European Conference of Ministers responsible for Regional Planning (CEMAT), Torremolinos, Spain, 20 May 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hildenbrand Scheid, A. Política de Ordenación del Territorio en Europa; Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 1996; ISBN 978-84-472-0315-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, K.L.; Rydén, L. 18. Spatial Planning and Management. In Rural Development and Land Use; Rydén, L., Karlsson, I., Eds.; Baltic University Press: Uppsala, Sweden, 2012; pp. 205–227. ISBN 978-91-86189-11-2. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion: Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength; CEC: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nuissl, H.; Heinrichs, D. Fresh Wind or Hot Air—Does the Governance Discourse Have Something to Offer to Spatial Planning? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, A. Cohesion, Coherence, Co-Operation: European Spatial Planning Coming of Age? Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faludi, A. Centenary paper: European spatial planning: Past, present and future. Town Plan. Rev. 2010, 81, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, A. Multi-Level (Territorial) Governance: Three Criticisms. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Trigal, L. Diccionario de Geografía Aplicada y Profesional: Terminología de Análisis, Planificación y Gestión del Territorio; Universidad de León: Leon, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cullingworth, B.J.; Caves, R. Planning in the USA: Policies, Issues, and Processes, 2013th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Orea, D. Ordenación Territorial, 3rd ed.; Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Urban Policy Studies, University of Manchester; Department of Town and Regional Planning, University of Sheffield. Measuring the Outcomes of Spatial Planning in England. Final Report; Royal Town Planning Institute: Stowmarket, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzini, D. Introduction: Crisis and renewal of contemporary urban planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhout, B.; Othengrafen, F.; Sykes, O.J. Neo-liberalization Processes and Spatial Planning in France, Germany, and the Netherlands: An Exploration. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Baker, M.; Kidd, S. Monitoring Spatial Strategies: The Case of Local Development Documents in England. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2006, 24, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, L.O.; Shahumyan, H.; Williams, B.; Convery, S. Scenarios and Indicators Supporting Urban Regional Planning. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 21, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Marques Da Costa, E. Monitoring and evaluation of policies: Methodological contribution based on the Portugal case study. In De la Evaluación Ambiental Estratégica a la Evaluación de Impacto Territorial: Reflexiones Acerca de la Tarea de Evaluación = (From Strategic Environmental Assessment to Territorial Impact Assessment: Reflections about Evaluation Practice); Farinós i Dasí, J., Ed.; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2011; pp. 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, D.; Nadin, V. Shifts in territorial governance and the Europeanization of spatial planning in Central and Eastern Europe. In Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: Building on EU Enlargement; Adams, N., Cotella, G., Nunes, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 154–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A.; Grijzen, J.; Van’t Klooster, S.A. Strong Stories: How the Dutch are Reinventing Spatial Planning; Design and Politics; 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Villanueva, L.F. La Implementación de las Políticas; Grupo Editorial Miguel Ángel Porrua: Mexico City, Mexico, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hogwood, B.W.; Gunn, L.A. Policy Analysis for the Real World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós i Dasí, J. Desarrollo Territorial y Gobernanza: Refinando significados desde el debate teórico pensando en la práctica. Un intento de aproximación fronética. Desenvolv. Reg. Debate 2015, 5, 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Girardot, J. Inteligencia Territorial y Transición Socio-Ecológica. Rev. Andal. Relac. Lab. 2010, 23, 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- National Environmental Policy Act (Public Law 91–190). 1969; 42 U. S. Code, Chapter 55; pp. 4321–4347. Available online: https://www.fsa.usda.gov/Internet/FSA_File/nepa_statute.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- UN. System of Social and Demographic Statistics. Draft Guidelines on Social Indicators; United Nations Publications; Statistical Commission: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Indicators of Sustainable Development. Guidelines and Methodologies; United Nations, Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benabent Fernández de Córdoba, M. Introducción a la Teoría de la Planificación Territorial; Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benabent Fernández de Córdoba, M. La Ordenación del Territorio en España: Evolución del Concepto y de su Práctica en el Siglo XX; Universidad de Sevilla, Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes: Seville, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benabent Fernández de Córdoba, M. Los planes de ordenación del territorio en España. De la instrumentación a la gestión. In Agua, Territorio y Paisaje: De los Instrumentos Programados a la Planificación Aplicada: V Congreso Internacional de Ordenación del Territorio = 5th International Congress for Spatial Planning: Málaga 22, 23 y 24 de Noviembre de 2007; Sánchez Pérez-Moneo, L., Troitiño Vinuesa, M.Á., Eds.; Asociación Interprofesional de Ordenación del Territorio (FUNDICOT): Madrid, Spain, 2009; pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Elorrieta Sanz, B. La Planificación Territorial en el Estado Español a la luz de las Políticas Territoriales Europeas. De la Teoría a la Praxis. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós i Dasí, J.; Romero González, J.; Salom, J. Cohesión e Inteligencia Territorial: Dinámicas y Procesos Para una Mejor Planificación y Toma de Decisiones; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feria Toribio, J.M.; Rubio Tenor, M.; Santiago Ramos, J. Los planes de ordenación del territorio como instrumentos de cooperación. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2005, 39, 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hildenbrand Scheid, A. La política de ordenación del territorio de las Comunidades Autónomas: Balance crítico y propuestas para la mejora de su eficacia. Rev. Derecho Urban. Medio Ambient. 2006, 40, 79–139. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Jiménez, M.I. La Ordenación del Territorio en las Comunidades Autónomas. Desarrollo Normativo. Polígonos. Rev. Geogr. 2014, 26, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel-lo i Colom, O. Ordenar el Territorio: La Experiencia de Barcelona y Cataluña; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Rodríguez, A. Ordenación del territorio en una sociedad española inmersa en el cambio global. Ciudad. Rev. Inst. Univ. Urban. Univ. Valladolid 2012, 15, 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Urkidi Elorrieta, P. Policies of land management in the Basque Autonomous Community, 1990–2006. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2010, 15, 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zoido Naranjo, F. Ordenación del territorio en Andalucía: Reflexión personal. Cuad. Geogr. Univ. Granada 2010, 47, 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Benabent Fernández de Córdoba, M. Treinta años de ordenación del territorio en el estado de las autonomías. In El Planejament Territorial a Catalunya a Inici del Segle XXI; Castañer, M., Ed.; Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Societat Catalana d’Ordenació del Territori: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; pp. 140–165. ISBN 978-84-9965-121-7. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrey Vázquez, J.A.; Rodríguez González, R. Instrumentos de ordenación del territorio en España. In Territorio. Ordenar Para Competir; Rodríguez González, R., Ed.; Netbiblo: Oleiros, La Coruña, Spain, 2010; pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cuyás Palazón, M. Urbanismo Ambiental y Evaluación Estratégica; S.A. ATELIER LIBROS: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Orea, D.; Gómez Villarino, M.; Gómez Villarino, A. Evaluación Ambiental Estratégica: Un Instrumento Para Integrar el Medio Ambiente en la Elaboración de Planes y Programas; Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cutaia, F. Strategic Environmental Assessment: Integrating Landscape and Urban Planning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós i Dasí, J. De la Evaluación Ambiental Estratégica a la Evaluación de Impacto Territorial: Reflexiones Acerca de la Tarea de Evaluación = (From Strategic Environmental Assessment to Territorial Impact Assessment: Reflections about Evaluation Practice); Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles. Manifiesto por Una Nueva Cultura del Territorio 2006. Available online: http://www.geografos.org/images/stories/interes/nuevacultura/manifiesto-por-una-nueva-cultura-del-territorio-d5.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Hernández Martínez, E. Por Una Nueva Cultura del Territorio. EL País 2008. Available online: http://elpais.com/diario/2008/04/25/andalucia/1209075726_850215.html (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Albrechts, L. Ingredients for a More Radical Strategic Spatial Planning. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 42, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Reframing strategic spatial planning by using a coproduction perspective. Plan. Theory 2013, 12, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A. Practicing Strategic Planning: In Search of Critical Features to Explain the Strategic Character of Plans. disP Plan. Rev. 2013, 49, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodbol-Mekkes, P.H.; Van der Valk, A.; Korthals Altes, W.K. The Netherlands spatial planning doctrine in disarray in the 21st century. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Pérez-Moneo, L.; Troitiño Vinuesa, M.Á. Agua, Territorio y Paisaje: De los Instrumentos Programados a la Planificación Aplicada: V Congreso Internacional de Ordenación del Territorio = 5th International Congress for Spatial Planning. Málaga 22, 23 y 24 de Noviembre de 2007; Asociación Interprofesional de Ordenación del Territorio (FUNDICOT): Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- López Estrada, R.E.; Deslauriers, J.P. La entrevista cualitativa como técnica para la investigación en Trabajo Social. Margen Rev. Trab. Soc. Cienc. Soc. 2011, 61, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and of the Council. Directive 2001/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 June 2001 on the assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment. Off. J. Eur. Union 2001, 197, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Law 9/2006, de 28 de abril, sobre evaluación de los efectos de determinados planes y programas en el medio ambiente (In force until 12 December 2013). Boletín Oficial del Estado 2006, 102, 16820–16830. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2006/04/29/pdfs/A16820-16830.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- Law 21/2013, de 9 de diciembre, de evaluación ambiental. Boletín Oficial del Estado 2013, 296, 98151–98227. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2013/12/11/pdfs/BOE-A-2013-12913.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- European Parliament and of the Council. Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE). Off. J. Eur. Union L 2007, 108, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish National Observatory of Sustainability (OSE, Observatorio de la Sostenibilidad en España). Available online: http://www.observatoriosostenibilidad.com (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- Law 35/2002, de 20 de diciembre, de Ordenación del Territorio y Urbanismo de Navarra. Boletín Oficial del Estado 13, 1885–1941. Available online: http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2003/01/15/pdfs/A01885-01941.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2017).

- García Martínez, M. El proceso de evaluación territorial, algo más que seguimiento. In De la Evaluación Ambiental Estratégica a la Evaluación de Impacto Territorial: Reflexiones Acerca de la Tarea de Evaluación = (From Strategic Environmental Assessment to Territorial Impact Assessment: Reflections about Evaluation Practice); Farinós i Dasí, J., Ed.; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2011; pp. 331–348. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós i Dasí, J. Inteligencia Territorial para la planificación y la gobernanza democráticas: Los observatorios de los territorios. Rev. Proyecc. 2011, 5, 45–69. [Google Scholar]

| Aspects | Evaluation | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Accountability, information, improvement of the design and implementation of the plan | To ensure that what is planned and regulated is actually enforced |

| When it is performed | Before, during, and after implementation of the plan | During implementation of the plan |

| Who performs it | External or internal evaluators | Team in charge of the plan |

| Content of the process | Assess relevance, usefulness, effectiveness and efficiency | Measure the performance and results |

| Aim of the process | Assess the adequacy of the plan | Correct deviations |

| Notion of public action | Allows questioning the plan | Does not question the plan |

| Profile of Interviewees | Andalusia | Valencia |

|---|---|---|

| Technical staff (public administration) | 1 | 3 |

| Professionals | 1 | 1 |

| Academics | 3 | 2 |

| Policy makers | 3 | 1 |

| Provisions | Number of Times Mentioned (Maximum of 15 Regional Laws) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring commission | 7 | Body in charge of monitoring the plan. |

| Monitoring and management reports | 12 | Provisions for the monitoring, modification and review of the plan, but with no detailed reference to the specific contents of the report. |

| Monitoring and management indicators | 3 | Evaluation and monitoring indicators are only briefly mentioned in the regional laws. |

| Public consultation and participation | 15 | Only in 6 cases is the issue of public participation mentioned and only in two cases a public participation project is mentioned. In the other cases, a public consultation period of only two months is mentioned. |

| Provisions for Strategic Environmental Assessment | 15 | All regional laws must transpose the SEA Directive (2001/42/CE) and the latest amendments of the laws do transpose it. |

| Territorial Observatories and/or Spatial Information Systems | 4 | Only four territorial observatories and/or Spatial Information Systems are mentioned in regional spatial planning laws. Evaluation and monitoring indicators are only briefly mentioned in the laws. In many cases it is the regional spatial plans that prescribe their creation. |

| Procedure | Document Submitted by the Project Manager | Administrative Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (regular procedure) Title II, Chapter 1, Section 1 | Initial Strategic Document along with the Draft Plan | Scope statement, along with a public consultation period |

| Strategic Environmental Study along with public participation | Strategic Environmental Report along with a public consultation period, once the required environmental report has been approved | |

| STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (simplified procedure) Title II, Chapter 1, Section 2 | Initial Strategic Document along with the Draft Plan | Strategic Environmental Report along with a period of public consultation |

| Region | Regional Spatial Planning Law (Year) | Territorial Observatory |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 1994 | - Territorial Observatory of Andalusia |

| - Spatial Information System for Andalusia (SDI) | ||

| Aragon | 2009 | - Spatial Information Documentation Centre |

| - Spatial Information System for Aragon (SDI) | ||

| Asturias | 2004 | * Sustainability Observatory of Asturias (OSE) |

| Balearic Islands | 2000 | * Spatial Development and Sustainability Observatory (OSE) |

| Canary Islands | 2000 | - Permanent Sustainable Development Observatory |

| - Observatory on Telecommunications and Information Society | ||

| Cantabria | 2001 | * Geographical Information System for Cantabria (SDI) |

| Castile and Leon | 1998 | * Spatial Information System of Castile Leon (SDI) |

| Castile-La Mancha | 2010 | * Information System of Castile La Mancha (SDI) |

| Catalonia | 1983 | * Landscape Observatory of Catalonia |

| Valencia | 2004 | - Landscape and Spatial Studies Institute |

| - Spatial Information System (SDI) | ||

| Extremadura | 2002 | * Territorial Observatory Centre for the Alentejo Extremadura (SDI) |

| Galicia | 1995 | - Spatial Studies Institute (law amended in 2007) |

| - Spatial Information System for Galicia (SDI) | ||

| Madrid | 1995 | |

| Murcia | 2005 | - Spatial Reference System |

| * Sustainability Observatory for the Murcia region (OSE) | ||

| Navarre | 2002 | - Territorial Observatory of Navarre |

| - Spatial Information System of Navarre (SDI) | ||

| Basque Country | 1990 | * Spatial Information System of the Basque Country (SDI) |

| La Rioja | 2006 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Segura, S.; Pedregal, B. Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Spatial Plans: A Spanish Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101706

Segura S, Pedregal B. Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Spatial Plans: A Spanish Case Study. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101706

Chicago/Turabian StyleSegura, Sergio, and Belen Pedregal. 2017. "Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Spatial Plans: A Spanish Case Study" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101706