1. Introduction

After three centuries of development in the gaming industry, Macau was now referred to as “Monte Carlo of the Orient” and “Las Vegas of the East”. By the end of 2015, there were 23 casinos in the Macau Peninsula and 13 on the Taipa Island. The market shares, based on the number of casinos, were as follows: 55.6% for SJM, 16.7% for Galaxy, 11.1% for Venetian and Melco Crown, and 2.7% for Wynn and MGM [

1]. Tax from gaming represented over 70 percent of the government revenue in 2009. With an average of 6 percent growth per year since 2000, the gaming revenue in Macau exceeded Las Vegas occasionally and this made Macau the largest gaming city in the world [

1] (see

Figure 1).

Gambling companies included Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) information in their annual reports and websites as a societal marketing tool [

3]. Responsible Gambling (RG) had been a recurring issue in Macau’s chief executive report since 2007 and in many of the major gambling operators’ annual report. Throughout the development of the gaming industry in Macau and the increasing amount of gaming facilities, people increased their concerns on the issues created by gambling. The major concern from the opposing parties was problem gambling or addictive gambling Problem gambling, characterized by difficulties limiting time and money spent gambling [

4]. Problem gambling had increased by 1.7% percentage point from 2003 to 2007 [

5] and had been expanding across the communities. Problem gambling was not the only issues created by the over concentration on the gambling industry. Casinos usually offered a more lucrative employment package, such as wages, working environment, meals, and health insurance. This made other businesses difficult to recruit or retain talents. Fong, Fong and Li (2011) [

6] estimated the social cost of gambling increased over twofold from 2003 to 2007 and expected the cost continue to increase.

To reduce the adverse impacts of the gambling industry, Macau government provided assistance to problem gamblers and their associated relatives to resolve their problems. For example, the DICJ and other institutions, such as the University of Macau, held “Responsible Gambling Awareness Week” each year to provide information regarding the adverse effect of addictive gambling to the public and the employees from casino with the objective to help these parties develop a positive attitude toward gambling. Furthermore, Macau government formed “Responsible Gaming Work Preparation Unit” with other concerned institutes to construct responsible gaming policies and the corresponding administrative procedures [

7].

Researchers in the tourism and hospitality industry began to research in CSR in recent years [

8]. While many researches focused on the benefits of CSR activities [

9], Hancock (2011) [

10] showed that in some circumstances, such as a bar within a casino, businesses would perform irresponsibly because the liquor served in the casino was directly linked to bar revenue and more importantly, the liquor kept people gambling and spending, and hence the businesses would have a very loose enforcement on liquor regulations and requirements. The measurement and dimensionality of the CSR were important issues in this study. Because of the CSR and RG in gambling industry was still a recent issue, few studies had endeavored to develop sound measurement items to investigate the CSR activities in Macau. This study offered a review of the CSR issues being addressed in the Macau gaming industry. In order to attain the above objectives, there were two main research questions of this study. The first question was what are the CSR dimensions that have been used in Macau gambling industry? The second question was how important are CSR dimensions which have been implemented in Macau gambling industry? In particular, the specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- 1.

Evaluate the CSR performance of the gambling operators in Macau

- 2.

Create a measurement scale of CSR practices of Macau gambling companies

- 3.

Provide recommendations and suggestions to gaming industry.

3. Methodology

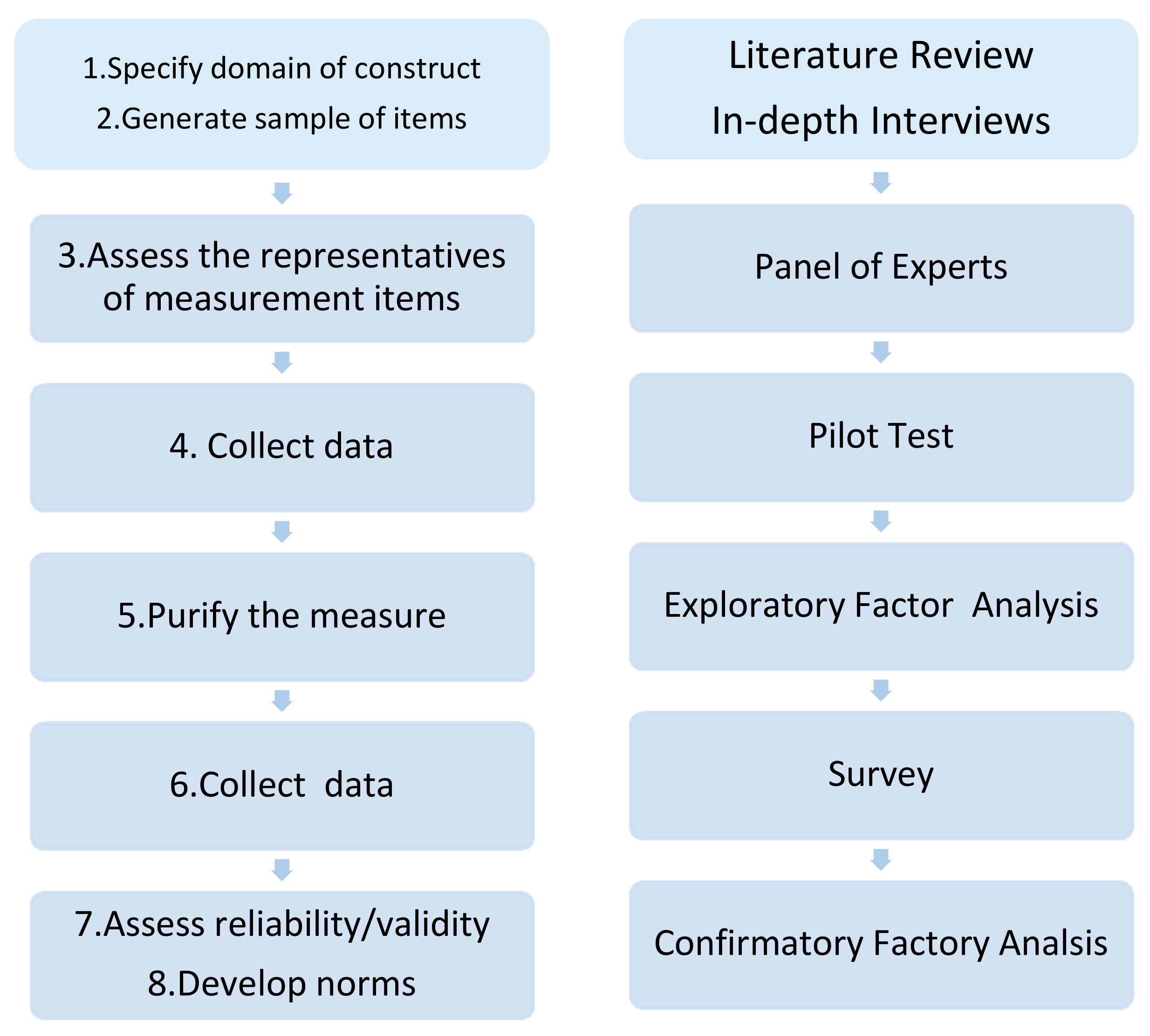

This study followed Churchill’s (1979) [

70] methodological proposal, which was based on a standard procedure for developing measurement instrument, to design a new multi-item measurement scale that included items previously used in stakeholder theory regarding tourist experience. An eight-step approach, which included quantitative and qualitative research methods, was adopted in this study [

70]. This study employed qualitative methods to review tourism and leisure research regarding participants’ experiences to generate a set of items and constructs domains of CSR practice. The researchers interviewed three panel experts using open-ended questions and conducted a content analysis of the responses. The panel experts were from Senior Vice President of Galaxy Entertainment Group, academia for tourism study of City University of Macau and senior manager of SJM Holdings Limited. The questionnaire contained two sections and was generated from the characteristics of the gambling industry in Macau.

Section 1 involved the respondents’ demographic information.

Section 2 assessed the CSR dimensions in Macau gambling industry. Data analysis was applied using the constant comparison technique [

71], which was a systematic method for recording, coding, and analyzing data. By combining the items generated from two sources (the open-ended survey and literature review), CSR in this study was operationalized by six dimensions, including customers, employees, shareholders, environment, government and community [

38,

46,

51]. Bases of measurement 38 items were developed. The content validity of the scale was analyzed through pilot testing which was collected through a convenience sample of 59 respondents who were part-time students and working in gambling industry for efficacy and clarity. As a result of this process, 32 item were included in the scale and used for the main survey which respondents were asked to evaluate all items on a 5-point Likert-type scale in which a score of 1 indicated strongly disagree with the statement, and a score of 5 signified total agreement with the statement. The sample size was 60 employees for each gambling operator. Finally, a total of 360 questionnaires were distributed to employees of 6 gambling operators, and 306 usable questionnaires were collected.

This study employed an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify the dimensionality of CSR practice in the gaming industry. Kaiser-Myer-Olki (KMO) and the Barlett’s Test of Sphericity were conducted to check the validity of the factor analysis. The validity of the factor analysis consisted of two parts. The first part was the correlation matrix, which was tested by the Barlett’s Test. The rule of thumb is when then inter-item correlation is above 0.30, the correlations were considered as substantial. The second part was the sample adequacy, which was tested by the KMO test. The factor reliability was analyzed through Cronbach’s alpha and item to total correlation. In this analysis process, 9 items were deleted due to high cross loadings. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.945. The KMO test and the Barlett’s test suggested that the final model should include 23 items (significance level 0.0001). Based on the results from the screen plot and eigenvalue (both greater than 1), the factors and the items explained over 92% of all variance. As a result, 23 items were included in the scale and used for order confirmatory factor analysis (see

Table 1).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) used the covariance matrix to verify the factor structure identified from the results from EFA. The meaning of validity was whether accurate information can be extracted from the analysis. The validity analysis for this study included both content and construct validity. Content validity tested the representativeness of the questionnaire items. There were no reports of misunderstanding during the pilot test. The interviewees stated that the items were easily understood, which indicated good content validity [

76]. The CFA was one of the most effective tools for testing construct validity. According to Campbell and Fiske (1959) [

77], construct validity typically tested the extent to which the data provide; (a) convergent validity, the extent to which different assessment methods show similar measurements of the same trait; ideally, these values should be moderately high; and (b) discriminant validity, the extent to which independent assessment methods showed divergent measurements of different traits; ideally, these values should demonstrate minimal convergence. The next step assessed the convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was evaluated by checking all factor loadings and the values of the average variance extracted. The second-order factor model was used to find measurement errors and modifying coefficient paths. The final items will be developed (see

Figure 3).

5. Discussion and Implications

Apart from a substantial amount of literature on CSR, there was a lack of empirical research testing and measuring of CSR activities in the gambling industry. There were many researches in the literature with application of CSR in different industries. Therefore, the understanding of the industrial specific factors toward CSR was necessary for appropriate adjustments in measurement scale [

62]. Considering the limitation of previously used scales, a strong current trend was the use of stakeholder theory to propose a new dimensioning of CSR composed of the particular activities in gaming industry, which is Responsible Gambling. According to Churchill’s (1979) [

70] methodological approach, this study followed both the qualitative and quantitative approach to develop a measurement scale. Based on the review of literature and discussions with gambling managers and experts, six CSR domains, including employee, customer, shareholder, environment, community and government, were identified. In order to test the adequacy of this new CSR measurement scale, a quantitative study based on personal surveys with gambling employees was designed. A total of 306 usable questionnaires were collected.

The first interesting result of this study was the confirmation of the multidimensional nature of CSR, which was consistent with the findings of previous research in stakeholder theory [

38,

46,

51]. Within the framework, Responsible Gambling included employee, customer, community and government. However, the coefficient on customer was insignificant and therefore, this measurement item was deleted. From the employee’s perspective, the Responsible Gambling was insignificant toward customers. Specifically, the two questions measuring Responsible Gambling toward customers, “Our company cares about customers’ psychological problems” and “Our company should provide family with prevention programs for gamblers who could not control their gambling behavior”, were not important from the employees’ perspective. This result was contrary to Song, Lee, Lee, and Song (2015) [

88], which the authors included RG toward customers in their measurement model. On one hand, their results showed that the company should have a responsibility toward the customers. On the other hand, our results showed the contrary. One possible reason for such a difference was history of gambling and culture. The sample in Song et al (2015) [

88] was from Korea while the sample of this study was from Macau. Macau had a much longer history of gambling. This meant that gambling has been part of many Macau people’s life since the day they born. Furthermore, Responsible Gambling has become a growing concern in Macau since 2010. Employees’ understanding of the responsible of the company could be very different.

Second, from employee’s perspective, this study showed that the attributes of CSR consists of employee, customer, shareholder, environment, community and government. However, the factor loading across these six attributes were different. According to

Table 6, since shareholders, government and customers dominated the top 10 of mean test. Therefore, the most important dimensions were shareholders, government and customer. The government dimension was important because it was related to licenses renewal and regulations [

46]. One of the reasons why the shareholder dimension was important was, since these six gaming corporation were publicly listed, the filing of CSR report would attract CSR concerning investors. The least important were environment and community. The questions concerning community were “Our company targets sustainable development and creation of a better life for future generations” and “Our company cares about public psychological problems”. Therefore, the employees did not believe that the gaming corporations were concerned about the sustainable development Macau. The question concerning environment was “Our company tries minimize its unfavourable and damaging effects on the natural environment”. This coincided with the pattern of development in Macau (or China), which was based on destruction of the environment. Many of the land used to build casino/hotels were from land reclamation.

Finally, the coexistence of customer being the most important concern in CSR and customer being the least important concern in RG showed that from the employees’ perspective, given the fact RG should be a part of CSR activities, the gaming corporations have been exerting a huge effort in promoting CSR to customers. This meant that the gaming corporations were not incapable of promoting socially responsible activities, given its success in promoting CSR but the concern was whether they were willing to promote responsible gambling. Given that most of the revenue of these gaming corporations came from casino or VIP rooms, and the purpose of RG was to reduce the amount of money people gamble, one would be very difficult to convince the shareholders or profit concerning parties to implement RG effectively.

This study contributed to the advancement of knowledge in the field of CSR. First, this study contributed to literature by developing measurement for the constructs of CSR in gambling industry in Macau. This study conducted holistic and comprehensive empirical research to investigate the measurement scale of CSR in gambling industry. This study contributed to the advancement of knowledge in the field of CSR through its practical application of stakeholder theory. Although there were several ways of measuring CSR in the literature, this study added to the literature by providing an extra measurement of CSR. Specifically, this study focuses on internal stakeholder perception. The perception of employees concerning the responsibility of stakeholder groups was captured through this instrument. Furthermore, from hospitality and tourism perspective, based on the industry specific, this study included RG as a factor of CSR. The results showed that this adjustment was significant and valuable in gambling industry.

This study also contributed to several practical applications. The first practical contribution of this study was the implications for government. The results showed that the government was a very important factor of both CSR and RG from the employees’ perspective and the government possessed the tools of rule, regulations and licenses renewal to encourage gaming corporations to focus on areas of weakness, such as environment and community. Furthermore, during the process of designing CSR or RG policies, the increase of promotion within the industry on the concerned areas might be beneficial.

Second, as the results of this study showed, customer groups was a very important and influential group to the gaming corporations. Hence, customers possessed the power to force the company to implement certain CSR practices. As customers increased their awareness in certain areas of weakness in CSR practices, companies would increase their awareness.

Third, from the industry’s perspective, this study was a reference for the implementation of CSR activities. The definition of CSR among the six gaming corporations in Macau could be significantly different [

50]. The measurement scale of this study provided CSR implementation from the employees’ perspective. As a management team of the gaming corporation, they could evaluate the performance of the current CSR by understanding the perception of employees. This would improve how the employees feel about the company. The bottom line was, regardless how good the CSR program could be, employees were the ultimate people to execute the program. Substantial improvement could be achieved when the philosophy between the management team and employees matched.

In conclusion, this study intended to study CSR activities and RG in gambling industry in Macau. A conceptual model was developed to measure scales including employee, customer, shareholder, environment, community and government. The results of this study were satisfactory and were supported by empirical evidence. The implications of the research findings were provided to hospitality and tourism industry. It was recommended that future research could be conducted in order to consolidate the knowledge and form rigorous theories in hospitality and tourism researches.