Impact of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident on Belief in Rumors: The Role of Risk Perception and Communication

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rumor Studies

2.2. Risk Perception Paradigm vs. Risk Communication Model

2.3. Risk Communication Model

2.4. Psychometric Paradigm

2.5. Risk Perception of Fukushima Nuclear Accident

3. Data and Measures

4. Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fukushima * P. Benefit = Belief in Rumor | P. Fukushima * P. Risk = Belief in Rumor | ||||||||||||

| B | SE | beta | B | SE | beta | B | SE | Beta | B | SE | Beta | ||

| P. Fukushima | 1.48 *** | 0.092 | 0.363 | 1.507 *** | 0.092 | 0.37 | P. Fukushima | 1.317 *** | 0.096 | 0.323 | 1.368 *** | 0.096 | 0.336 |

| P. Benefit | −1.055 *** | 0.092 | −0.258 | −0.99 *** | 0.094 | −0.242 | P. Risk | 1.22 *** | 0.11 | 0.261 | 1.229 *** | 0.109 | 0.263 |

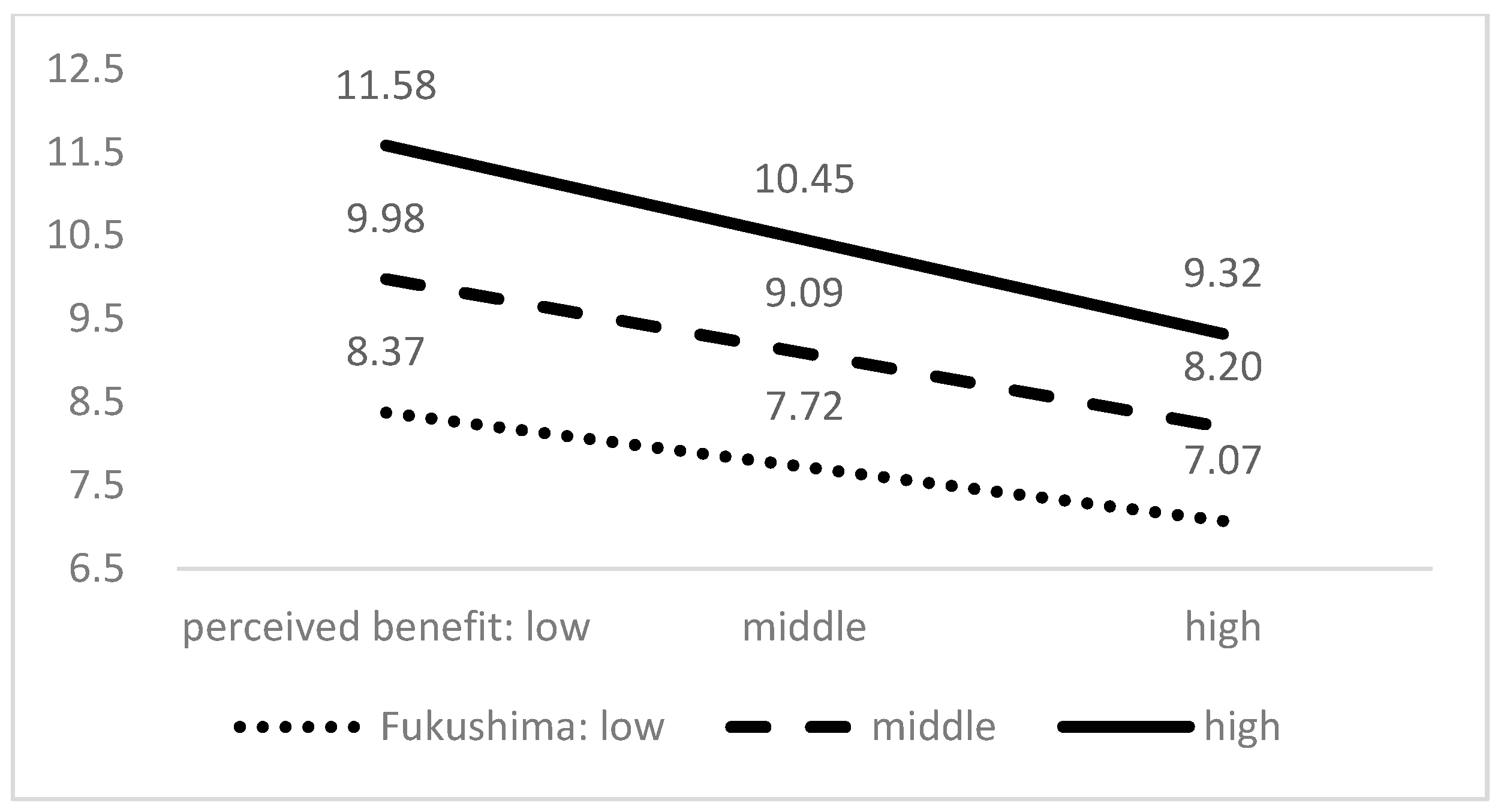

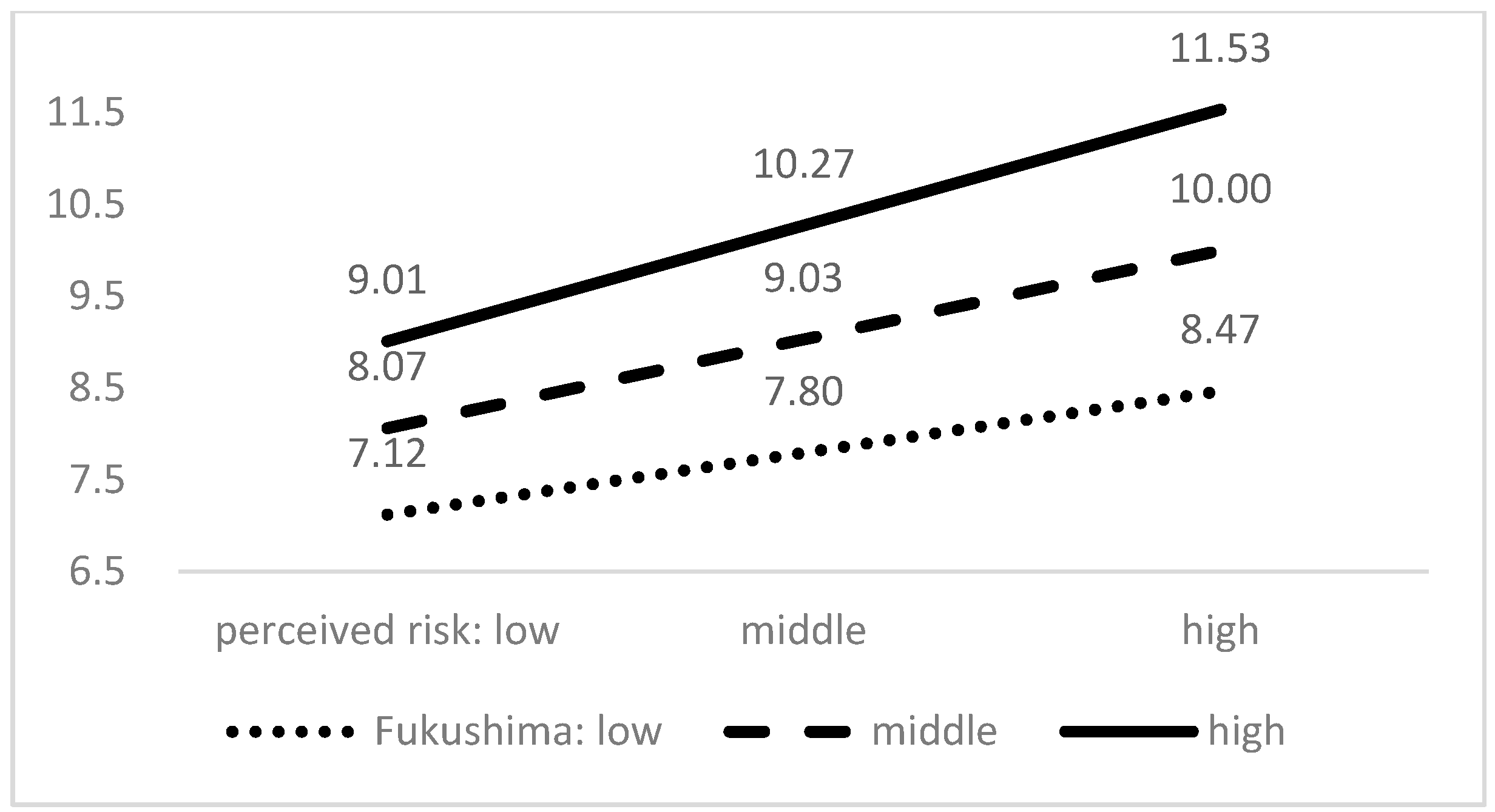

| Interaction Term | −0.295 *** | 0.098 | −0.068 | Interaction Term | 0.414 *** | 0.1 | 0.093 | ||||||

| F-value | 236.522 *** | 161.495 *** | F-value | 231.723 *** | 161.820 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.232 | 0.236 | R2 | 0.228 | 0.236 | ||||||||

| R2 Change | 0.231 | 0.235 | R2 Change | 0.227 | 0.235 | ||||||||

| Simple Slope Test | Low | B = −0.723 *** se = 0.144 t = −5.038 | Simple Slope Test | Low | B = 0.855 *** se = 0.140 t = 6.085 | ||||||||

| Middle | B = −0.99 *** se = 0.130 t = −7.592 | Middle | B = 1.229 *** se = 0.140 t = 8.773 | ||||||||||

| High | B = −1.257 *** se = 0.114 t = −11.038 | High | B = 1.603 *** se = 0.0143 t = 11.194 | ||||||||||

| Effect Size | 0.012 | Effect Size | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| P. Fukushima * Trust = Belief in Rumor | P. Fukushima * Knowledge = Belief in Rumor | ||||||||||||

| B | SE | Beta | B | SE | Beta | B | SE | Beta | B | SE | Beta | ||

| P. Fukushima | 1.474 *** | 0.092 | 0.362 | 1.473 *** | 0.092 | 0.362 | P. Fukushima | 1.652 *** | 0.093 | 0.406 | 1.661 *** | 0.093 | 0.408 |

| Trust | −0.852 *** | 0.078 | −0.246 | −0.836 *** | 0.078 | −0.242 | Knowledge | −0.41 *** | 0.095 | −0.099 | −0.418 *** | 0.095 | −0.101 |

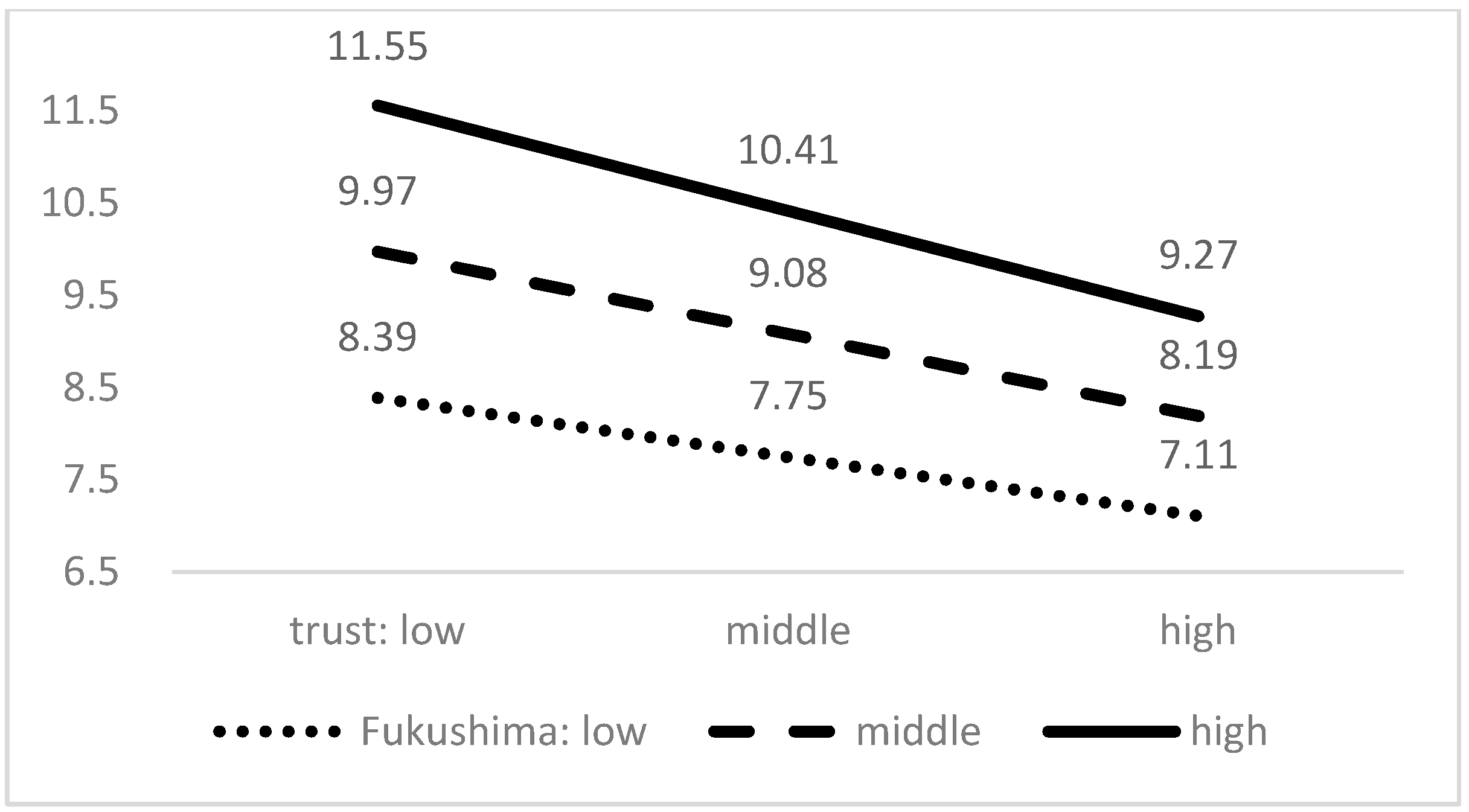

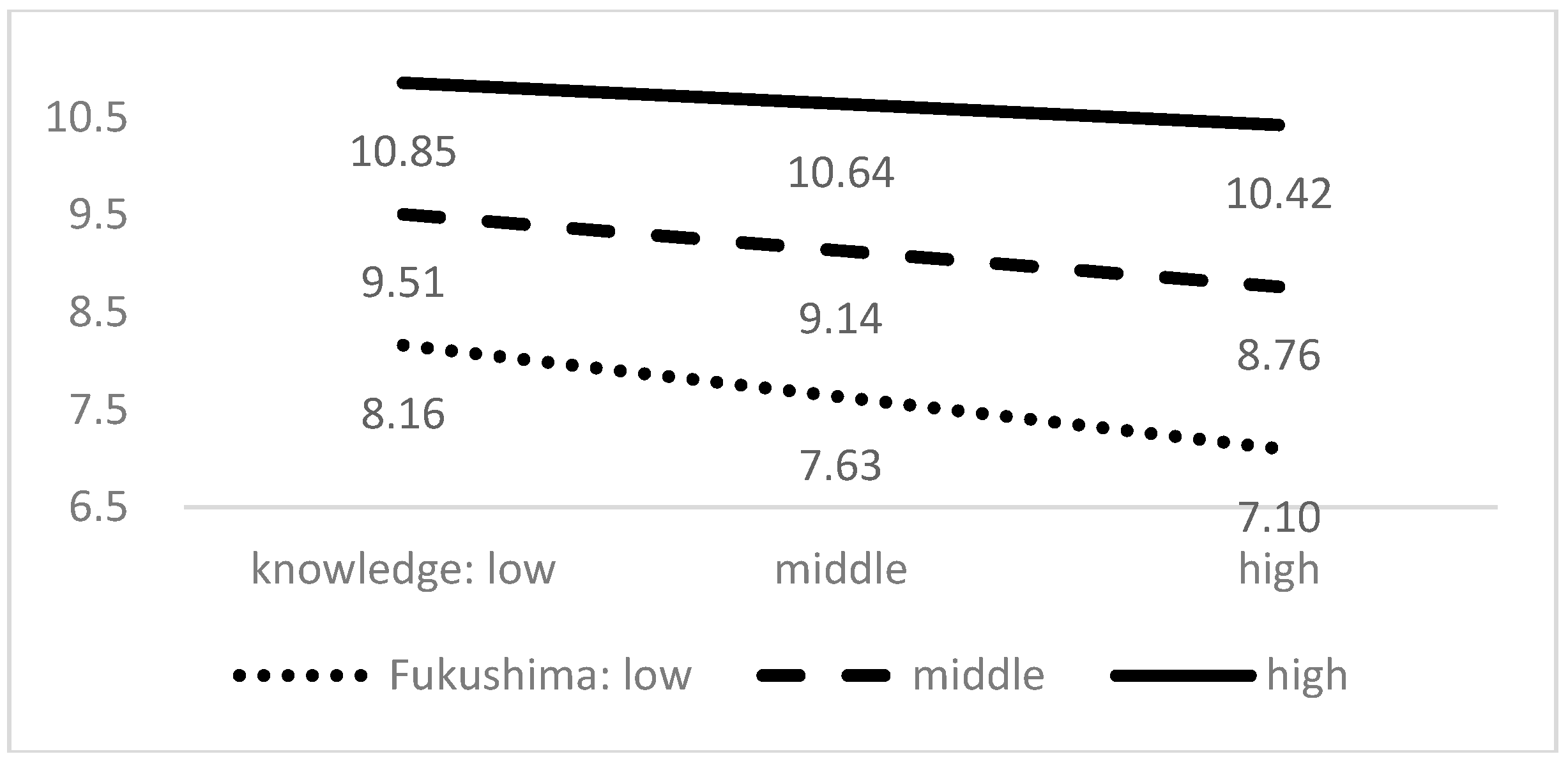

| Interaction Term | −0.261 *** | 0.082 | −0.071 | Interaction Term | 0.196 * | 0.103 | 0.044 | ||||||

| F-value | 228.797 *** | 156.836 *** | F-value | 169.071 *** | 114.117 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.231 | R2 | 0.177 | 0.179 | ||||||||

| R2 Change | 0.225 | 0.229 | R2 Change | 0.176 | 0.178 | ||||||||

| Simple Slope Test | Low | B = −0.600 *** se = 0.111 t = −5.411 | Simple Slope Test | Low | B = −0.595 *** se = 0.135 t = −4.397 | ||||||||

| Middle | B = −0.836 *** se = 0.095 t = −8.810 | Middle | B = −0.418 *** se = 0.115 t = −3.641 | ||||||||||

| High | B = −1.072 *** se = 0.104 t = −1.300 | High | B = −0.241 * se = 0.130 t = −1.857 | ||||||||||

| Effect Size | 0.02 | Effect Size | 0.009 | ||||||||||

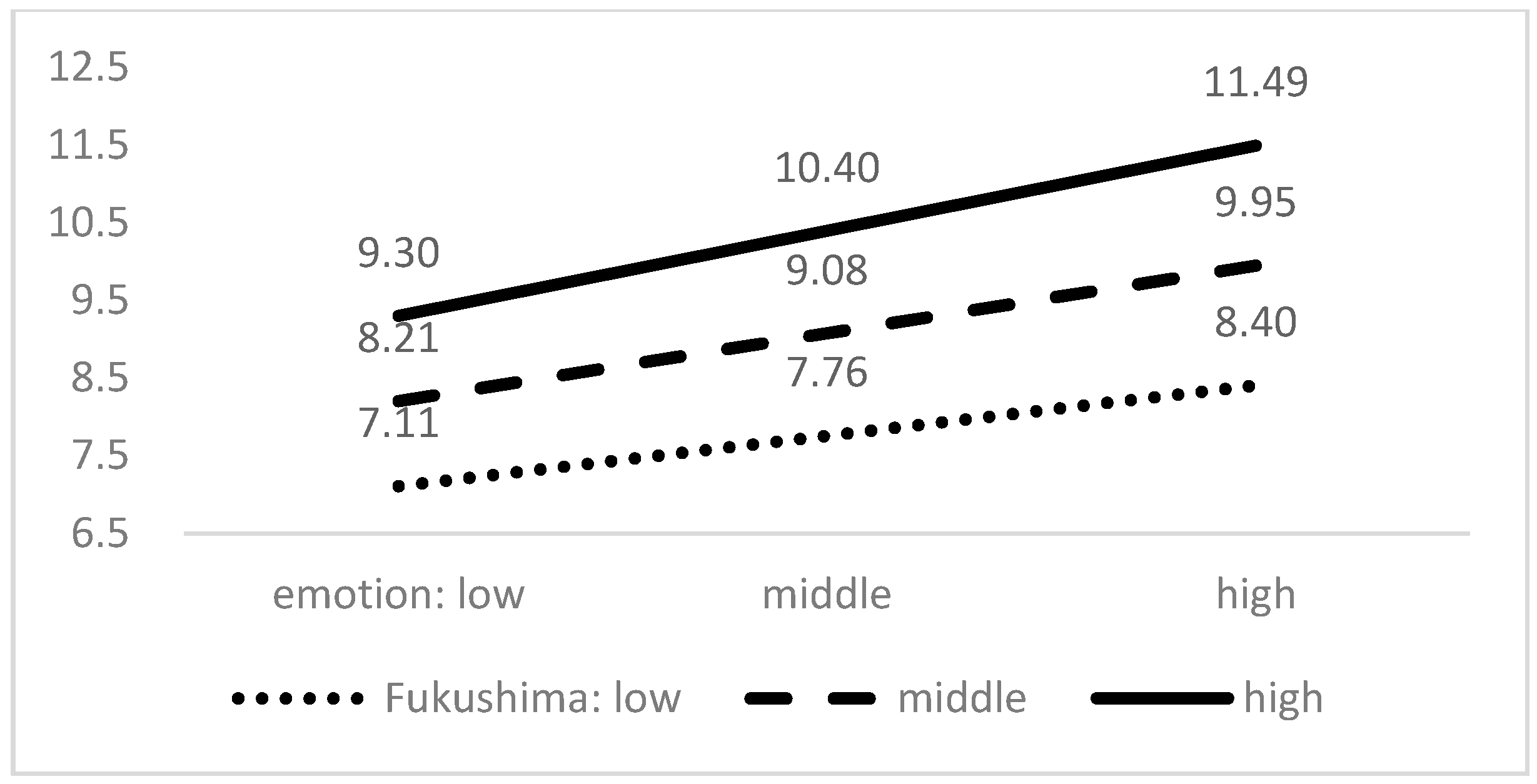

| P. Fukushima * Emotion = Belief in Rumor | |||||||||||||

| B | SE | Beta | B | SE | Beta | ||||||||

| P. Fukushima | 1.424 *** | 0.093 | 0.35 | 1.459 *** | 0.094 | 0.358 | |||||||

| Emotion | 1.223 *** | 0.113 | 0.249 | 1.163 *** | 0.114 | 0.236 | |||||||

| Interaction Term | 0.33 *** | 0.112 | 0.067 | ||||||||||

| F-value | 228.752 *** | 156.156 *** | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.226 | 0.23 | |||||||||||

| R2 Change | 0.225 | 0.229 | |||||||||||

| Simple Slope Test | Low | B = 0.865 *** se = 0.165 t = 5.225 | |||||||||||

| Middle | B = 1.163 *** se = 0.136 t = 8.570 | ||||||||||||

| High | B = 1.461 *** se = 0.138 t = 1.571 | ||||||||||||

| Effect Size | 0.012 | ||||||||||||

References

- Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, W. Effect of the Fukushima nuclear disaster on global public acceptance of nuclear energy. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Hammitt, J.K.; Bi, J.; Yang, L. Effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on the risk perception of residents near a nuclear power plant in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19742–19747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujikawa, N.; Tsuchida, S.; Shiotani, T. Changes in the factors influencing public acceptance of nuclear power generation in Japan since the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. How a nuclear power plant accident influences acceptance of nuclear power: Results of a longitudinal study before and after the Fukushima disaster. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, A.; Meguro, K.; Hener, M. Comparing the disaster information gathering behavior and post-disaster actions of Japanese and foreigners in the Kanto area after the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. In Proceedings of the 2012 WCEE, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012; Available online: http://www.iitk.ac.in/nicee/wcee/article/WCEE2012_2649.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2017).

- Ozeki, Y. The Risks of Web Media, as Shown by Disaster. Available online: http://astand.asahi.com/magazine/wrnational/2011042000017.html (accessed on 18 October 2011). (In Japanese).

- The Asahi Shimbun. TEPCO: Radioactive Substances Belong to Landowners, Not Us. The Asahi Shimbun. 24 November 2011. Available online: http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/social_affairs/AJ201111240030 (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- Jacob, B.; Mawson, A.R.; Payton, M.; Guignard, J.C. Disaster Mythology and Fact: Hurricane Katrina and Social Attachment. Public Health Rep. 2008, 123, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, A. Psychology of Rumor. Public Opin. Q. 1944, 8, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://news.chosun.com (accessed on 31 July 2013).

- DiFonzo, N.; Bordia, P. Rumor Psychology: Social and Organizational Approaches; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- DiFonzo, N.; Bordia, P.; Rosnow, R.L. Reining in rumors. Organ. Dyn. 1994, 23, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W.; Postman, L.J. An analysis of rumor. Public Opin. Q. 1947, 10, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W.; Postman, L.J. The Psychology of Rumor; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow, R.L. Inside Rumor: A Personal Journey. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difonzo, N.; Bordia, P. Rumor, gossip and urban legends. Diogenes 2007, 54, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. The Perception of Risk; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff, B.; Slovic, P.; Lichtenstein, S.; Read, S.; Combs, B. How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sci. 1978, 9, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Fischhoff, B.; Lichtenstein, S. Characterizing perceived risk. In Perilous Progress: Managing the Hazarak of Technology; Kates, R.W., Hohenemser, C., Kasperson, J.X., Eds.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wildavsky, A. A cultural theory of responsibility. In Bureaucracy and Public Choice; Lane, J., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell, G.; Allum, N.; Wagner, W.; Kronberger, N.; Torgersen, H.; Hampel, J. GM foods and the misperception of risk perception. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, M.D.; Macoubrie, J. Public perceptions about nanotechnology: Risks, benefits and trust. J. Nanopart. Res. 2004, 6, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. Risk communication: Towards a rational discourse with the public. J. Hazard. Mater. 1992, 29, 465–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; The University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperson, R.E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H.S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Ratick, S. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 1988, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lim, C.; Jeong, J.; Wang, J.; Park, C. Analyzing the risk judgement about Fukushima nuclear accident and nuclear power by integrating the risk-perception paradigm with risk communication model. Korea Public Adm. J. 2014, 23, 113–144. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo, C.W.; McComas, K.A. The Function of credibility in information processing for risk perception. Risk Anal. 2003, 23, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, E.G. Birth control discontinuance as a diffusion process. Stud. Fam. Plan. 1984, 15, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Chou, W.-S.; Hsu, Y.-L. The factors of influencing college student’s belief in consumption-type internet rumors. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2009, 2, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.H.; Han, I. The effect of negative online consumer reviews on product attitude: An information processing view. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chaiken, S. The heuristic–systematic model in its broader context. In Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology; Chaiken, S., Trope, Y., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, P. How idle is idle talk? One hundred years of rumor research. Diogenes 2013, 54, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnow, R.L.; Kimmel, A.J. Rumor. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; Oxford University Press/American Psychological Association: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 7, pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches; WIlliam C. Brown: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Issue involvement can increase or decrease persuasion by enhancing message-relevant cognitive responses. J. Pers. Soc. Pschol. 1979, 37, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, C.W. Heuristic–systematic information processing and risk judgment. Risk Anal. 1999, 19, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Petty, R.E.; Morris, K.J. Effects of need for cognition on message evaluation, recall, and persuasion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklinski, J.H.; Metlay, D.S.; Kay, W.D. Citizen knowledge and choices on the complex issue of nuclear energy. AJPS 1982, 26, 615–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; White, H.M. The public’s understanding of radiation and nuclear waste. J. Radiol. Prot. 1987, 7, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, D. The Case for a ‘Deficit Model’ of Science Communication. 2005. Available online: http://medsci.free.fr/docsderef/Dickson2005_Deficit%20model%20of%20science%20communication.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2017).

- Siegrist, M.; Cvetkovich, G. Perception of hazards: The role of social trust and knowledge. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slovic, P.; Layman, M.; Kraus, N.; Flynn, J.; Chalmers, J.; Gesell, G. Perceived risk, stigma, and potential economic impacts of a high-level nuclear waste repository in Nevada. Risk Anal. 1991, 11, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, E.; Slovic, P. The role of affect and worldviews as orienting dispositions in the perception and acceptance of nuclear Power1. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 26, 1427–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J. The psychology of rumor: A study relating to the great Indian earthquake of 1934. Br. J. Psychol. 1935, 41, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura, E. Experience of technological and natural disaster and their impact on the perceived risk of nuclear accidents after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan 2011: A cross-country analysis. J. Socio-Econ. 2012, 41, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prati, G.; Bruna Zani, B. The effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on risk perception, antinuclear behavioral intentions, attitude, trust, environmental beliefs, and values. Environ. Behav. 2012, 45, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, H. Case studies and theory in political science. In Handbook of Political Science; Greenstein, F., Polsby, N., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 7, pp. 79–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publication: Thusand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, A. Comparative politics and the comparative method. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1971, 65, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Kim, S. Testing the heuristic/systematic information-processing model (HSM) on the perception of risk after the Fukushima nuclear accidents. J. Risk Res. 2015, 18, 840–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.P.; Miller, D.C.; Schafer, W.E. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertzel, T. Belief in Conspiracy Theories. Polit. Psychol. 1994, 15, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasek, J.; Stark, T.H.; Krosnick, J.A.; Tompson, T. What motivates a conspiracy theory? Birther beliefs, partisanship, liberal-conservative ideology, and anti-black attitudes. Elect. Stud. 2014, 40, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnow, R.L. Psychology of rumor reconsidered. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 87, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator—Mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.F.; Austin, L.; Jin, Y. How publics respond to crisis communication strategies: The interplay of information form and source. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F.; Utz, S.; Glocka, S. Crisis communication and social media. On the effects of medium, media credibility, crisis type and emotions. In Proceedings of the Etmaal Conference, Leuven, Belgium, 9–10 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, B.F. The blog-mediated crisis communication model: Recommendations for responding to influential external blogs. J. Public Relat. Res. 2010, 22, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.M. Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima: An analysis of traditional and new media coverage of nuclear accidents and radiation. Bull. At. Sci. 2011, 67, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriumi, F.; Sakaki, T.; Shinoda, K.; Kazama, K.; Kurihara, S.; Noda, I. Information Sharing on Twitter during the 2011 Catastrophic Earthquake. In Proceedings of the International World Wide Web Conference Committee (IW3C2), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 13–17 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.-Y. Social media use and goals after the Great East Japan Earthquake. First Monday 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.; Lean, M. The Fukushima nuclear crisis reemphasizes the need for improved risk communication and better use of social media. Health Phys. 2012, 103, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhakami, A.S.; Slovic, P. A psychological study of the inverse relationship between perceived risk and perceived benefit. Risk Anal. 1994, 14, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Perception Paradigm | Risk Communication Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Discipline |

|

|

| Key variable |

|

|

| Assumption about mode of judgment |

|

|

| Method |

|

|

| Strength |

|

|

| Weakness |

|

|

| Variable | Item | Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Benefit | Nuclear power energy will contribute to solving current climate change problems. | 0.835 |

| Nuclear power energy will solve environmental problems. | ||

| Nuclear power energy is cheap and provides stability. | ||

| Nuclear power contributes to economic development. | ||

| Perceived Risk | I personally feel threatened by nuclear power. | 0.781 |

| Nuclear power produces hazardous waste. | ||

| Nuclear power is harmful to people’s health. | ||

| Nuclear power stations are dangerous. | ||

| The nuclear power stations in our country operate safely®. | ||

| Knowledge | I know the organization that regulates the safety of nuclear power. | 0.893 |

| I know to some extent the law regarding safety regulations on nuclear power. | ||

| I can explain the issues pertaining to nuclear power to other people. | ||

| I know the policy on and issues related to nuclear power. | ||

| Stigma | bright↔dark | 0.910 |

| clean↔dirty | ||

| progressive↔retrogressive | ||

| good↔bad | ||

| positive↔negative | ||

| warm↔cold | ||

| hopeful↔pessimistic | ||

| friendly↔unfriendly | ||

| Quantity of Information | I read a lot of information related to nuclear energy on the Internet. | 0.895 |

| I have received a lot of information related to nuclear energy on the Internet. | ||

| Source Credibility | The government provides (① trustworthy, ② exact, ③ fact-based objective, ④ fair, ⑤ valid, ⑥ expertise) information on nuclear safety and regulation. | 0.954 |

| Usefulness of Information | Information gathered from the Internet is helpful in understanding issues pertaining to nuclear power. | 0.861 |

| Information about nuclear power obtained from the Internet helps in understanding the main problem of nuclear power. | ||

| Receiver’s Involvement | I am interested in nuclear-related disputes on the Internet. | 0.865 |

| I am usually engrossed in debates on nuclear issues on the Internet. | ||

| Receiver’s Ability | I have the ability to transmit information about nuclear power through the Internet. | 0.096 |

| I can transfer information related to nuclear power energy as I want. |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Belief in Rumors | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Fukushima accident | 0.409 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Communication factor | 3. Source credibility | −0.297 *** | −0.215 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 4. Quantity of information | 0.275 *** | 0.206 *** | −0.363 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. Usefulness of information | 0.076 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.099 *** | −0.026 | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. Receiver’s involvement | 0.082 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.003 | 0.076 **** | 0.257 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. Receiver’s ability | 0.049 * | 0.017 | 0.036 | 0.041 | 0.389 *** | 0.376 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Psychometric factor | 8. Perceived benefit | −0.322 *** | −0.178 *** | 0.398 *** | −0.474 *** | 0.002 | −0.006 | −0.017 | 1 | ||||

| 9. Perceived risk | 0.367 *** | 0.329 *** | −0.288 *** | 0.357 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.106 *** | 0.009 | −0.34 *** | 1 | ||||

| 10. Trust | −0.316 *** | −0.192 *** | 0.676 *** | −0.361 *** | 0.04 | −0.012 | 0.029 | 0.403 *** | −0.351 *** | 1 | |||

| 11 Knowledge | −0.114 *** | −00.035 | 0.123 *** | −0.026 | 0.189 *** | 0.368 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.147 *** | −0.06 ** | 0.137 *** | 1 | ||

| 12. Emotion | 0.333 *** | 0.24 *** | −0.409 *** | 0.875 *** | −0.033 | 0.02 | −0.002 | −0.536 *** | 0.429 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.108 *** | 1 | |

| Mean | 9.13 | 3.787 | 2.947 | 2.922 | 3.198 | 2.617 | 2.747 | 3.354 | 3.799 | 2.64 | 2.341 | 3.084 | |

| S.D. | 3.683 | 0.904 | 0.738 | 0.822 | 0.683 | 0.818 | 0.864 | 0.899 | 0.787 | 1.064 | 0.892 | 0.749 | |

| B | S.E. | Beta | T-Value | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic Factors (F1) | constant | 3.900 *** | 0.979 | 3.982 | 0.000 | |

| Age | −0.012 * | 0.007 | −0.043 | −1.835 | 0.067 | |

| Gender (female) | 0.808 *** | 0.164 | 0.110 | 4.938 | 0.000 | |

| Education level | −0.099 | 0.228 | −0.010 | −0.434 | 0.664 | |

| Household income | 8.865 × 10−5 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.869 | 0.385 | |

| Communication Factors (F2) | Source credibility | −0.372 ** | 0.149 | −0.075 | −2.493 | 0.013 |

| Quantity of information | −0.166 | 0.204 | −0.037 | −0.814 | 0.416 | |

| Usefulness of information | 0.244 * | 0.127 | 0.045 | 1.925 | 0.054 | |

| Receiver’s involvement | 0.131 | 0.109 | 0.029 | 1.195 | 0.232 | |

| Receiver’s ability | 0.209 * | 0.107 | 0.049 | 1.960 | 0.050 | |

| Psychometric Factors (F3) | Perceived benefit | −0.429 *** | 0.108 | −0.105 | −3.986 | 0.000 |

| Perceived risk | 0.618 *** | 0.117 | 0.132 | 5.271 | 0.000 | |

| Trust | −0.272 *** | 0.106 | −0.079 | −2.570 | 0.010 | |

| Knowledge | −0.259 *** | 0.101 | −0.063 | −2.565 | 0.010 | |

| Emotion | 0.442 * | 0.241 | 0.090 | 1.829 | 0.068 | |

| Risk perception of the Fukushima accident (F4) | 1.148 *** | 0.095 | 0.282 | 12.067 | 0.000 | |

| F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 45.698 ***/0.306/0.299 | |||||

| F1 | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 19.992 ***/0.049/0.046 | ||||

| F2 | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 48.081 ***/0.133/0.130 | ||||

| F3 | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 81.988 ***/0.207/0.205 | ||||

| F4 | F-Value/R2/Ad. R2 | 315.736 ***/0.167/0.167 | ||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Kim, S. Impact of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident on Belief in Rumors: The Role of Risk Perception and Communication. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122188

Kim S, Kim S. Impact of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident on Belief in Rumors: The Role of Risk Perception and Communication. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122188

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Seoyong, and Sunhee Kim. 2017. "Impact of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident on Belief in Rumors: The Role of Risk Perception and Communication" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122188

APA StyleKim, S., & Kim, S. (2017). Impact of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident on Belief in Rumors: The Role of Risk Perception and Communication. Sustainability, 9(12), 2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122188