Self-Standing Hierarchical Porous Nickel-Iron Phosphide/Nickel Foam for Long-Term Overall Water Splitting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

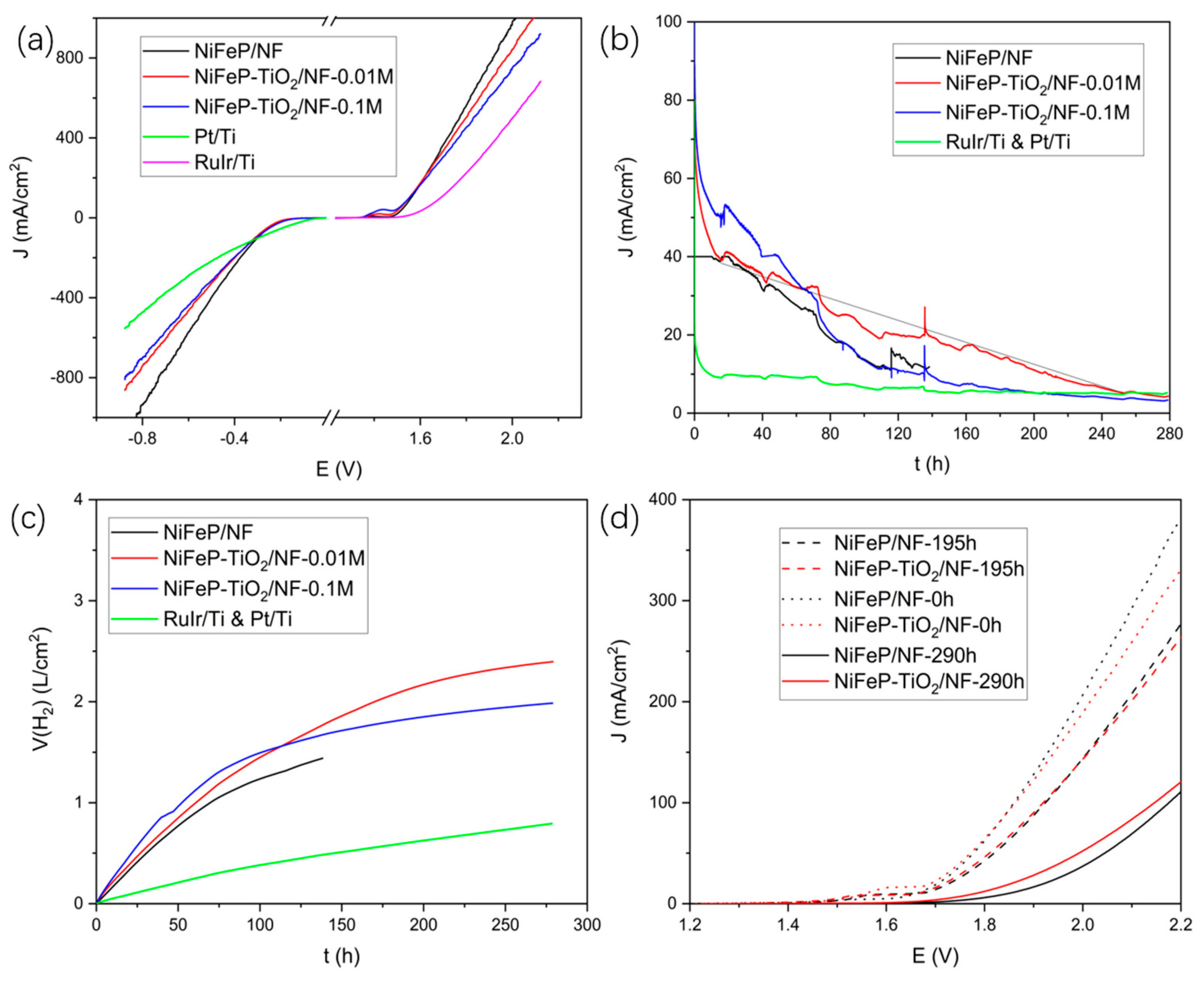

2.1. Preparation and Water-Splitting Performance of NiFeP/NF

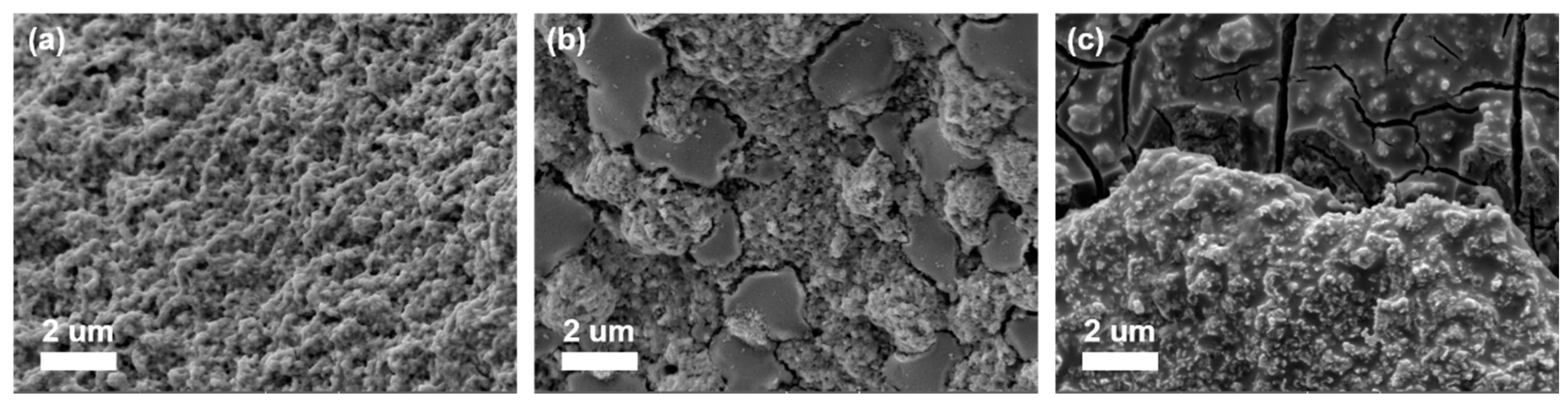

2.2. Analysis of NiFeP/NF after Long-Term Electrolysis and Improvement with TiO2 Coating

3. Experiment Materials

3.1. Preparation of NiFe Hydroxide/NF Precursor

3.2. Preparation of NiFeP/NF

3.3. Preparation of NiFeP-TiO2/NF

3.4. Preparation of Electrode

3.5. Characterization

3.6. Electrocatalytic Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Ren, Z.; Fu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tian, G.; Fu, H. NiSe-Ni0.85Se heterostructure nanoflake arrays on carbon paper as efficient electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Small 2018, 14, 1800763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; An, C.; Zhang, J. Interlayer expanded lamellar CoSe2 on carbon paper as highly efficient and stable overall water splitting electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 241, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Song, F.; Amal, R.; Ng, Y.H.; Hu, X. Efficient water splitting catalyzed by cobalt phosphide-based nanoneedle arrays supported on carbon cloth. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Li, Q.; Ma, X.; Chen, H.; Yuan, T.; Xu, X.; Wang, F. CoNi2S4 nanoparticle on carbon cloth with high mass loading as multifunctional electrode for hybrid supercapacitor and overall water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 554, 149598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.; Fan, P.; Zhang, H.; Huang, K.; Yang, C.; Yu, W.; Wei, H.; Zhong, M.; Wu, H.; Li, Y. Large-scale hierarchical oxide nanostructures for high-performance electrocatalytic water splitting. Nano Energy 2017, 35, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, R.; Tao, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Huo, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S. In-situ evolution of active layers on commercial stainless steel for stable water splitting. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 248, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, H.; Sadaf, S.; Walder, L.; Kuepper, K.; Dinklage, S.; Wollschläger, J.; Schneider, L.; Steinhart, M.; Hardege, J.; Daum, D. Stainless steel made to rust: A robust water-splitting catalyst with benchmark characteristics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2685–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Efficient electrochemical water splitting catalyzed by electrodeposited nickel diselenide nanoparticles based film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4718–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, H.-x.; Wang, Z.-l.; Meng, F.-l.; Zhang, X.-b. Integrated three-dimensional carbon paper/carbon tubes/cobalt-sulfide sheets as an efficient electrode for overall water splitting. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernäcker, C.I.; Rauscher, T.; Büttner, T.; Kieback, B.; Röntzsch, L. A powder metallurgy route to produce raney-nickel electrodes for alkaline water electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, F357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Guo, F.; Qian, J.; Li, H.; Zhou, M.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, Y.-Q.; Li, T.-T. Paintbrush-like Co doped Cu3P grown on Cu foam as an efficient janus electrode for overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 28833–28840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Manthiram, A. Direct growth of ternary Ni–Fe–P porous nanorods onto nickel foam as a highly active, robust bi-functional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 2496–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, R.; Karmakar, A.; Kumaravel, S.; Sankar, S.S.; Bera, K.; Nagappan, S.; Dhandapani, H.N.; Kundu, S. Revealing the pH-universal electrocatalytic activity of Co-doped RuO2 toward the water oxidation reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 14, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Li, F.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Cheng, T.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Q.; Huang, X. Single-site Pt-doped RuO2 hollow nanospheres with interstitial C for high-performance acidic overall water splitting. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl9271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitz, C.; Lasia, A. Experimental study and modeling of impedance of the her on porous Ni electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2001, 500, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Alhokbany, N.; Ahamad, T.; Alshehri, S.M. Investigation of enhanced electro-catalytic HER/OER performances of copper tungsten oxide@ reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites in alkaline and acidic media. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Doan, T.L.L.; Prabhakaran, S.; Tran, D.T.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, N.H. Hierarchical Co and Nb dual-doped MoS2 nanosheets shelled micro-TiO2 hollow spheres as effective multifunctional electrocatalysts for HER, OER, and ORR. Nano Energy 2021, 82, 105750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, C.A.; Libretto, N.J.; Harman-Ware, A.E.; Happs, R.M.; Ruddy, D.A.; Baddour, F.G.; Ferrell Iii, J.R.; Habas, S.E.; Schaidle, J.A. Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction over Cu3P Nanoparticles Generated via a Molecular Precursor Route. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 10435–10446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, N.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X. Self-supported Cu3P nanowire arrays as an integrated high-performance three-dimensional cathode for generating hydrogen from water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 9577–9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, R.; Ji, H.; Du, P. Crystalline Copper Phosphide Nanosheets as an Efficient Janus Catalyst for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popczun, E.J.; McKone, J.R.; Read, C.G.; Biacchi, A.J.; Wiltrout, A.M.; Lewis, N.S.; Schaak, R.E. Nanostructured nickel phosphide as an electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 13, 9267–9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, R.B.; Martirez, J.M.P.; Rappe, A.M. Active Role of Phosphorus in the Hydrogen Evolving Activity of Nickel Phosphide (0001) Surfaces. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 7718–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wen, P.; Itanze, D.S.; Kim, M.W.; Adhikari, S.; Lu, C.; Jiang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Geyer, S.M. Phosphorus-Rich Colloidal Cobalt Diphosphide (CoP2) Nanocrystals for Electrochemical and Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1900813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, G.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, T.; Jia, D. Template Construction of Porous CoP/COP2 Microflowers Threaded with Carbon Nanotubes toward High-Efficiency Oxygen Evolution and Hydrogen Evolution Electrocatalysts. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 12232–12239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Dang, Y.; He, J.; Tobin, Z.; Kerns, P.; Dou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, Y.; Suib, S.L. In Situ Growth of Ni2P–Cu3P Bimetallic Phosphide with Bicontinuous Structure on Self-Supported NiCuC Substrate as an Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalyst. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6919–6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Sun, K.; Lin, Y.; Cao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Zeng, L.; Cheong, W.-C.; Zhao, D.; Wu, K.; et al. Electronic structure and d-band center control engineering over M-doped CoP (M = Ni, Mn, Fe) hollow polyhedron frames for boosting hydrogen production. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Gan, L.; Zhang, R.; Lu, W.; Jiang, X.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, L. Ternary FexCo1–xP nanowire array as a robust hydrogen evolution reaction electrocatalyst with Pt-like activity: Experimental and theoretical insight. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 6617–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Schipper, D.E.; Leitner, A.P.; Thirumalai, H.; Chen, J.-H.; Xie, L.; Qin, F.; Alam, M.K.; Grabow, L.C.; Chen, S. Bifunctional metal phosphide FeMnP films from single source metal organic chemical vapor deposition for efficient overall water splitting. Nano Energy 2017, 39, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Q.; Wen, P.; Williams, T.B.; Adhikari, S.; Dun, C.; Lu, C.; Itanze, D.; Jiang, L.; Carroll, D.L.; et al. Colloidal Cobalt Phosphide Nanocrystals as Trifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting Powered by a Zinc-Air Battery. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Xia, Z.; Gao, W.; Ma, Y.; Qu, Y. Highly efficient and robust nickel phosphides as bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water-splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 10826–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.; Wu, J.Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Regier, T.; Wei, F.; Dai, H. An advanced Ni-Fe layered double hydroxide electrocatalyst for water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8452–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.J.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Jin, P.; Li, G.D.; Zou, X. A high surface area flower-like Ni-Fe layered double hydroxide for electrocatalytic water oxidation reaction. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 11592–11600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Lui, Y.H.; Zhou, L.; Tang, X.; Hu, S. An alkaline electro-activated Fe-Ni phosphide nanoparticle-stack array for high-performance oxygen evolution under alkaline and neutral conditions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 13329–13335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zou, Y.; Ye, Y.-Q.; Ouyang, T.; Xiao, K.; Liu, Z.-Q. Unveiling the active sites of Ni-Fe phosphide/metaphosphate for efficient oxygen evolution under alkaline conditions. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 7687–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, F.; McElhenny, B.; Luo, D.; Karim, A.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Heterogeneous Bimetallic Phosphide Ni2P-Fe2P as an Efficient Bifunctional Catalyst for Water/Seawater Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 31, 2006484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Kan, X.; Gan, L.Y.; Zhang, Z. Heterogeneous Bimetallic Phosphide/Sulfide Nanocomposite for Efficient Solar-Energy-Driven Overall Water Splitting. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10303–10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufond, M.E.; Chazalviel, J.-N.; Santinacci, L. Electrochemical Stability of n-Si Photoanodes Protected by TiO2 Thin Layers Grown by Atomic Layer Deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 031509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhai, B.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, X.; Diao, P. Dendritic CuBi2O4 Array Photocathode Coated with Conformal TiO2 Protection Layer for Efficient and Stable Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.J.; Mehrabi, H.; Schichtl, Z.G.; Coridan, R.H. Enhanced Electrochemical Stability of TiO2-Protected, Al-doped ZnO Transparent Conducting Oxide Synthesized by Atomic Layer Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 43691–43698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaaraman, S.; Grace, A.N.; Sellappan, R. Photoelectrochemical performance of a spin coated TiO2 protected BiVO4-Cu2O thin film tandem cell for unassisted solar water splitting. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 31380–31391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, C.; Carretero, N.M.; David, J.; Arbiol, J.; Andreu, T.; Morante, J.R. Insight into the degradation mechanisms of atomic layer deposited TiO2 as photoanode protective layer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 29725–29735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Du, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cho, K.; Chen, R.; Shan, B. Enhanced photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution at p-type CuBi2O4 photocathode through hypoxic calcination. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 9549–9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, Q.; Wu, H.; Li, F.; Liu, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, P.; Gao, L. Self-Standing Hierarchical Porous Nickel-Iron Phosphide/Nickel Foam for Long-Term Overall Water Splitting. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13091242

Han Q, Wu H, Li F, Liu J, Zhao L, Zhang P, Gao L. Self-Standing Hierarchical Porous Nickel-Iron Phosphide/Nickel Foam for Long-Term Overall Water Splitting. Catalysts. 2023; 13(9):1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13091242

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Qixian, Hongmei Wu, Feng Li, Jing Liu, Liping Zhao, Peng Zhang, and Lian Gao. 2023. "Self-Standing Hierarchical Porous Nickel-Iron Phosphide/Nickel Foam for Long-Term Overall Water Splitting" Catalysts 13, no. 9: 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13091242