Abstract

The complex [(κ3-(N,N,O-py2B(Me)OH)Ru(NCMe)3]+ TfO− (1) is a catalyst for transfer dehydrogenation of alcohols, which was designed to function through a cooperative transition state in which reactivity was split between boron and ruthenium. We show here both stoichiometric and catalytic evidence to support that in the case of alcohol oxidation, the mechanism most likely involves reactivity only at the ruthenium center.

1. Introduction

Dual site catalysts possess two active sites that cooperate to enable the formation and/or cleavage of functional groups that cannot be manipulated easily or selectively with single-site systems. Dual site catalysis involving ruthenium has been of high interest, particularly ligand-metal bifunctional catalysis wherein a proton in the ligand directs cleavage and formation of bonds to hydrogen [1,2,3,4]. Among other applications, such systems are of great research interest because of their potential for enabling formation and utilization of hydrogen [5,6,7].

Our group is developing bifunctional catalysts for manipulating hydride groups, e.g., C–H and other X–H bonds [8]. In our ongoing efforts we have recently reported a dual site ruthenium, boron complex (1) that has diverse oxidative reactivity [9], and in its synthesis uncovered a remarkable agostic interaction, which defines a very rare sample of an acetonitrile ligand being replaced by C–H bond [10,11]. This complex highlighted important potential synergy between the reactivity of the boron and ruthenium centers. More recently we have found that 1 is among the most robust and efficient homogeneous systems for ammonia borane dehydrogenation [12,13,14], which makes it a candidate for commercialization as a hydrogen storage system [15].

We report here on the mechanism of alcohol oxidation with 1. Because mechanistic understanding is empowering for the development of new catalytic methods [16,17], we aim to understand 1 so that we and other might more effectively harness its remarkable reactivity. Here we will present evidence to show that, by contrast to the system’s original design, this catalyst’s oxidation of alcohols to ketones involves bond forming and breaking at only the ruthenium center.

Design of a Dual Site Ruthenium, Boron Catalyst

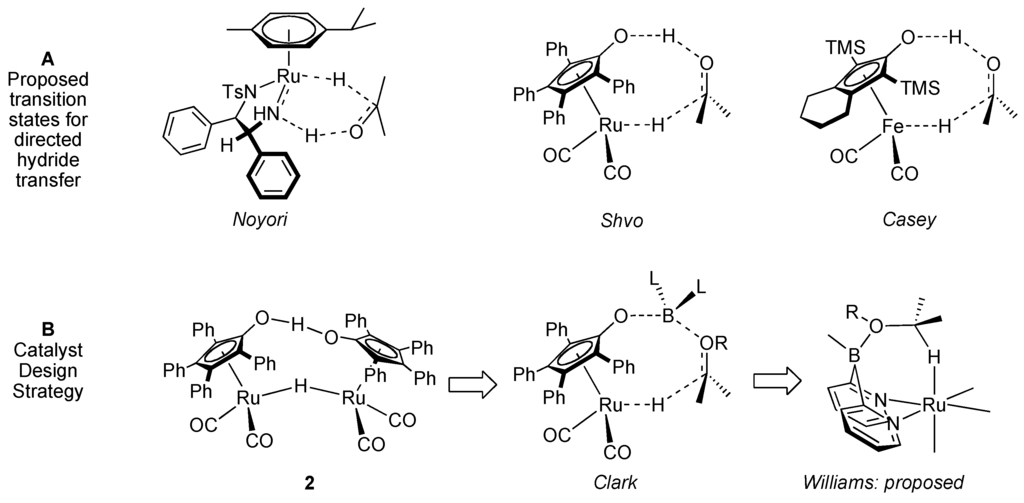

Our general design strategy to affect selective hydride manipulation is to devise catalysts that have two active sites that can work in concert to position and oxidize a particular substrate. Such a strategy is used prolifically in ligand, metal bifunctional catalysts, such as those pioneered by Noyori [18] and Shvo [19,20,21,22] (Figure 1). In these systems, a hydrogen bond is used to position a protic substrate with a C–H bond in the proximity of a ruthenium center, from which the hydrogen group is abstracted.

Figure 1.

Coordination-directed hydride transfer.

Our general strategy of devising a catalyst with a built-in Lewis acid to direct the metal to a particular substrate is analogous to these. Along these lines, the Shvo mechanism is similar to the Noyori systems and has been studied previously by Shvo [23], Casey [24,25], Bäckvall [6,26,27] us [28], and others. Alcohol oxidation with 1 has isotope effects on both C–H (kH/kD = 2.6) and O–H(kH/kD = 1.8), which indicates that both of these hydrogen atoms are transferred in (or possibly before) the rate-determining transition state (Figure 1A) [27]. Further, 1-catalyzed oxidation of 1-phenylethanol has a Hammett ρ value of −0.9, which is larger than expected for a transition state involving β-hydride elimination (ρ = −0.43) [29] or free-radical hydrogen atom transfer (ρ = −0.3) [30].

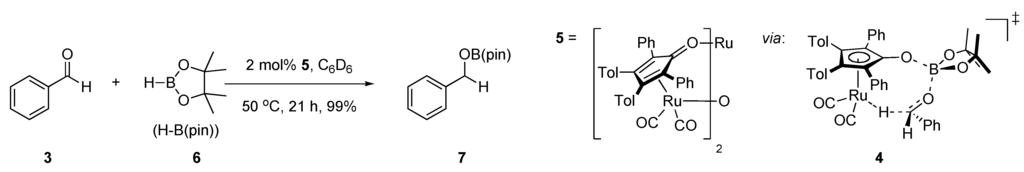

Our design is to replace the hydrogen atom in the Shvo transition state with a boron atom (Figure 1B) [31]. By replacing the proton in the transition state with a Lewis acid, we propose to enable abstraction of hydrides from groups other than alcohols [28]. Our first plan to prepare a dual site ruthenium, boron hydride transfer catalyst was to functionalize Shvo’s catalyst with a boronic ester as sketched in 4 (Scheme 1) [32]. Along these lines, Tim Clark has realized such a transition state with the Shvo scaffold in reduction chemistry, and has reported that 5 will catalyze aldehyde and aldimine hydroboration with a transition state such as 4 [33]. By contrast, we have not been able to observe oxidative chemistry with the Shvo system in the presence of pinacol borane.

Scheme 1.

A boron-functionalized homolog of the Shvo catalyst.

To overcome the apparent limitations of the Shvo system for catalytic, boron-directed oxidation, we prepared dual-site ruthenium, boron complexes 8 and 1 (Scheme 2) [9]. which are characterized by X-ray crystallography [34]. Our mechanistic design for dual site oxidation chemistry with these is sketched in Scheme 3C. In this plan, 1 will substitute an alcohol substrate for its bridging hydroxyl group, which will be driven by the formation of water. The result will be a bridging alkoxide (12), which we proposed should rearrange to enable hydride abstraction from the pendant alkoxyborate through a transition state akin to 12 to give a ruthenium hydride and ketone product (13).

Scheme 2.

Dual site ruthenium, boron complexes.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Stoichiometric Studies

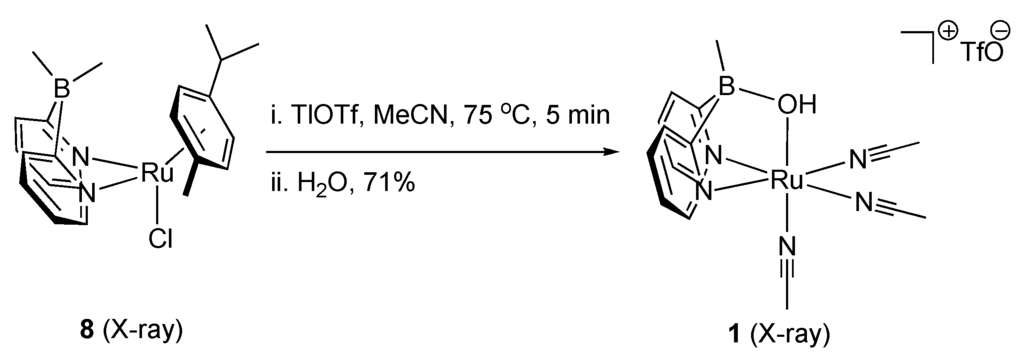

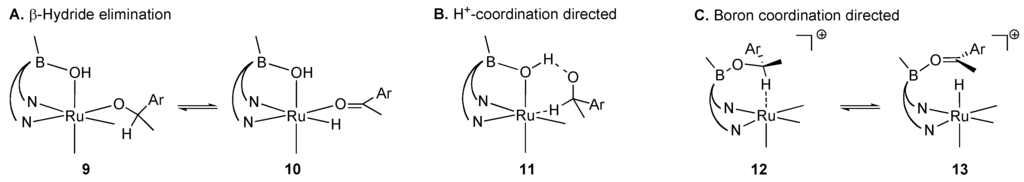

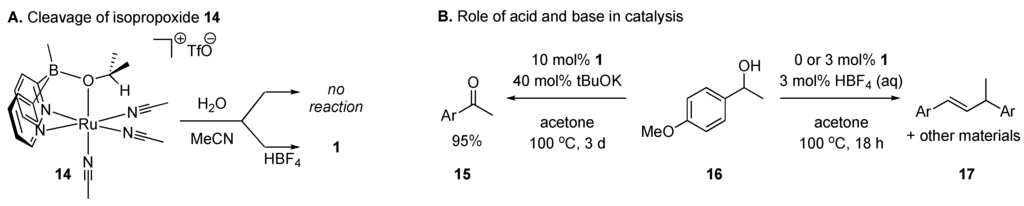

C–H bond cleavage steps of three likely candidates for the mechanism of alcohol oxidation with 1 are sketched in Scheme 3. They include (A) a β-hydride elimination from a coordinated alkoxide. This type of mechanism is common for transfer dehydrogenation of alcohols with phosphine-ligated ruthenium(II) catalysts [29,35]. A second possibility (B) is a Shvo-like mechanism wherein the bridging hydroxyl directs the alkoxide to the metal center [24,36]. Our designed mechanism (C) is also possible.

Our stoichiometric studies of this mechanism revealed key insights into the reactivity of the proposed intermediates (Scheme 4A). First we observed that substitution of the hydroxide bridge of 1 is slow: heating 1 in isopropanol did not result in hydroxide substitution at neutral pH. Conversely, the desired bridged isopropoxy complex 14 (independently prepared) is inert to reaction with neutral water in acetonitrile solution. This exchange is facile, however, in the presence of aqueous acid. Treatment of alcohol 16 with 1 results in divergent outcomes depending on conditions (Scheme 4B): when the catalyst is activated with acid, no oxidative pathways are observed. In these conditions, we see elimination and apparent carbocation chemistry with or without 1. In the presence of base, however, selective and high yielding oxidation of the alcohol to the corresponding ketone is possible (with concurrent formation of iPrOH-d6). Taken together, these observations indicate that 1’s μ-OH group is not labile under the conditions of alcohol oxidation catalysis.

Scheme 3.

Mechanisms for base-mediated oxidation with 1.

Scheme 4.

Labiality of μ-ORgroups in 1: Roles of acid and base.

2.2. Catalytic Studies

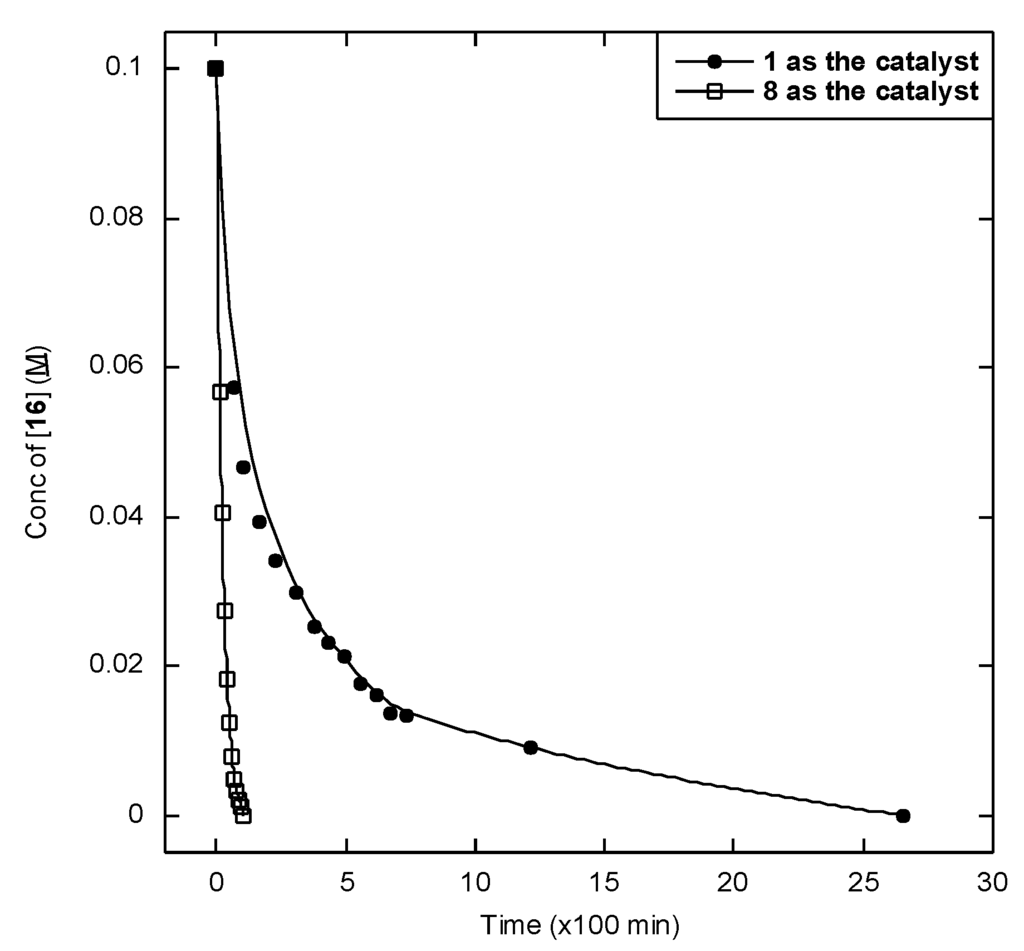

In catalytic experiments, we have shown that cymene adduct 8 is a more reactive catalyst for alcohol oxidation than 1 (Figure 2). This provides further data refuting a (B) or (C) class mechanism: a class (B) mechanism would require the presence of the μ-OH group of 1, and a class (C) mechanism would necessitate a free Lewis acid site on boron. Neither of these is available in catalyst precursor 8, yet alcohol oxidation with 8 is far faster than alcohol oxidation with 1 under analogous conditions.

In analyzing the above data, one must consider a scenario in which a methylborate group in 8 is cleaved in the course of the reaction to reveal a boron hydroxide or a free Lewis acid. To test this hypothesis, we compared the 11B NMR chemical shifts of the materials formed in situ at the conclusion of the reaction of 8 with 16 with the 11B chemical shifts of 8 and 1. The catalytic species in this reaction appear to speciate into three boron-containing moieties, which appear at 11B δ = −14.1, −14.7, and −15.4 ppm. By comparison, the corresponding 11B NMR chemical shifts for 8 and 1 are −12.0 and −8.1 ppm in acetone, respectively. Thus, because the 11B species of this reaction are upfield of 8 and 1 is downfield, we surmise that if a methylborate group is cleaved in 8 in the course of this reaction, it is not converted to a boron hydroxide.

Figure 2.

Oxidation of 16 (10 μL, 71 μmol) by 1 (4.1 mg, 8.7 μmol, 12 mol%) and 8 (4.6 mg, 8.7 μmol, 12 mol%) in acetone-d6 (0.7 mL) in the presence of potassium tert-butoxide (1.6 mg, 14 μmol, 20 mol%) at 100 °C in a sealed J-Young tube. Points are plotted for the concentration of 16 vs. time, where circles and squares respectively represent reactions catalyzed by 8 and 1.

3. Experimental

3.1. General Procedures

All air and water sensitive procedures were carried out either in a Vacuum Atmosphere glove box under nitrogen (0.5–10 ppm O2 for all manipulations) or using standard Schlenk techniques under nitrogen. Deuterated NMR solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories. Benzene-d6 and acetonitrile-d3 were dried over sodium benzophenone ketyl and calcium hydride, respectively, and distilled prior to use. Anhydrous iPrOH was distilled from NaOiPr, stirred over molecular sieves and silica gel for 20 h, then filtered through a Millipore filter prior to use. Shvo’s catalyst was purchased from Strem Chemicals. 1H and 11B NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian 600 spectrometer (600 MHz in 1H, 192 MHz in 11B) with chemical shifts reported in units of ppm. All 1H chemical shifts are referenced to the residual 1H solvent (relative to TMS). All 11B chemical shifts are referenced to a BF3-OEt2 in diglyme in a co-axial external standard (0 ppm). NMR spectra were taken in 8” J-Young tubes (Wilmad) with Teflon valve plugs. The NMR tubes were shaken vigorously for several minutes with chlorotrimethylsilane then dried in vacuo on a Schlenk line prior to use. Compound 1 and 8 were synthesized according to our published procedure [4].

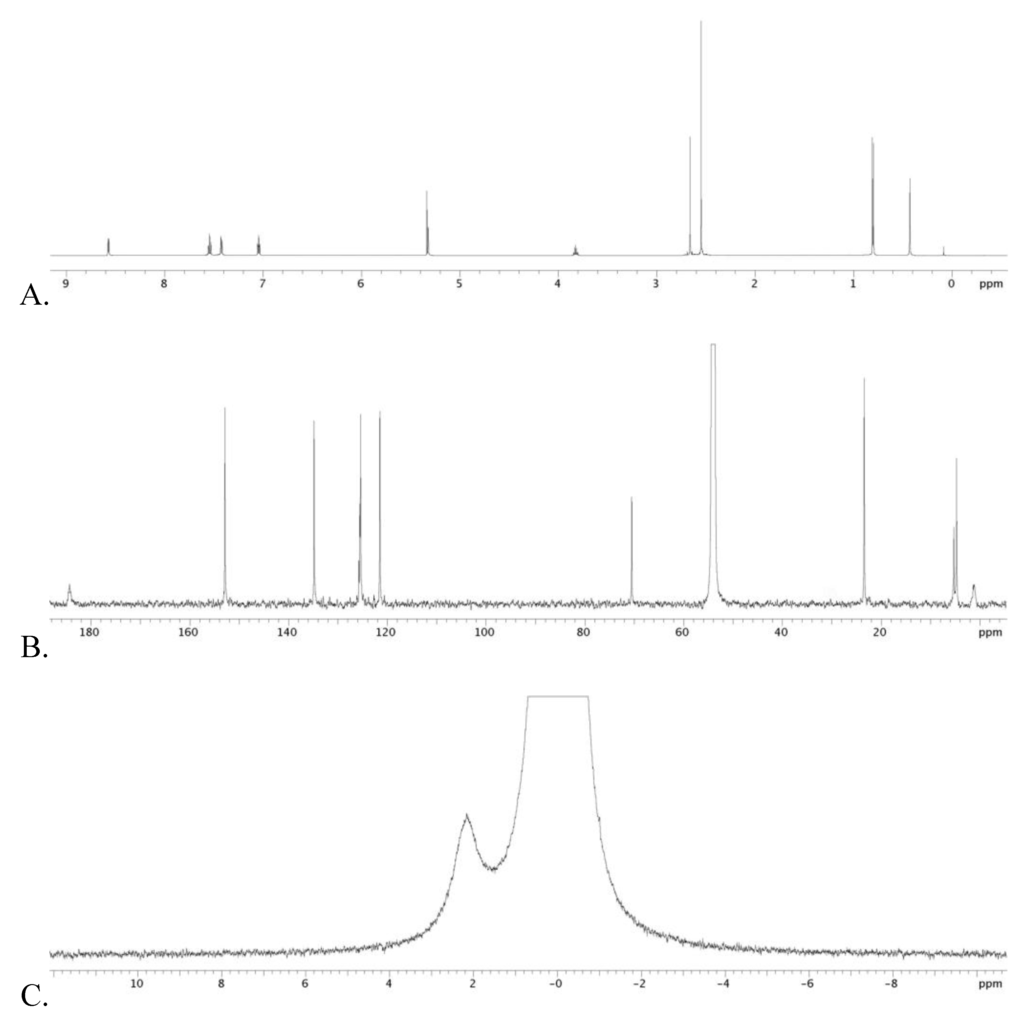

3.2. Trisacetonitrile μ-Isopropoxy Ruthenium Triflate 14

14 was generated in situ according to the following procedure. In a glove box, 1 (10.0 mg, 11 μmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (0.6 mL) in a 8 inch J-Young tube that had been pre-treated with chlorotrimethylsilane. Silane residue had been removed under reduced pressure before use. Trifluoroacetic anhydride (5.0 μL, 38 μmol, 2.0 eq.(molar equivalents)) was added to the tube. The mixture was then heated to 60 °C for 20 h and cooled to room temperature, then anhydrous iPrOH (7.3 μL, 96 μmol, 5 eq) was added to the J-Young tube in the glove box. The reaction mixture was heated at 60 °C for 20 h. All volatiles were removed under reduced pressure on the Schlenk line. Recrystallization from dichloromethane/hexane yielded a pale yellow solid 2.3 mg (21%) (see Figure 3 and, Figure 4 for NMR spectra).

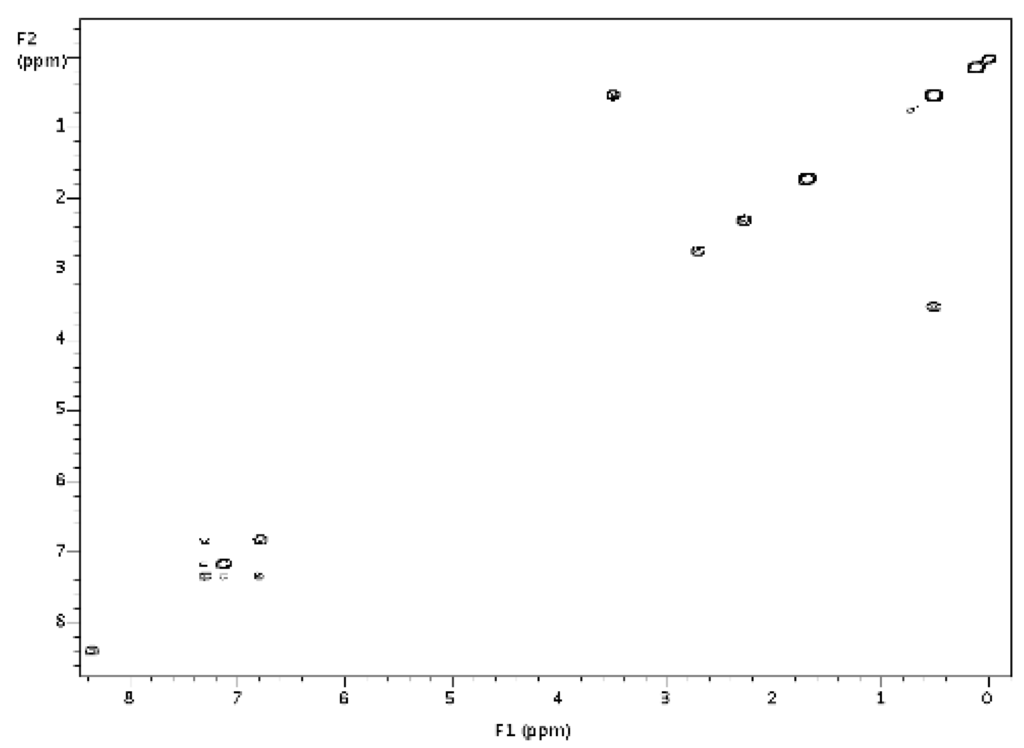

1H NMR (600 MHz in dichloromethane-d2 at 25 °C): δ = 8.57 (d, pyridyl 2H, J = 5.6 Hz), 7.59 (dt, pyridyl 2H, J = 1.6, 7.6 Hz), 7.39 (d, pyridyl 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.07 (dt, pyridyl 2H, J = 1.6, 6.6 Hz), 3.82 (m, (CH3)2CH-O, 1H), 2.66 (s, CH3CN axial, 3H), 2.55 (s, CH3CN equatorial, 6H), 0.80 (d, (CH3)2CH–O 6H, J = 6.4 Hz), 0.43 (s, CH3–B 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (150.84 MHz in dichloromethane-d2 at 25 °C) δ = 184.33 (broad s, ipso pyridyl-B), 152.87 (pyridyl), 134.81 (pyridyl), 125.73 (axial CH3CN), 125.53 (equatorial CH3CN), 125.39 (pyridyl), 121,48 (pyridyl), 70.49 ((CH3)2CH–O), 23.42 ((CH3)2CH–O), 5.27 (axial CH3CN), 4.70 (equatorial CH3CN), 1.33 (broad s, CH3-B). 11B{1H} (192 MHz in dichloromethane-d2 at 50 °C): δ = 2.17.

Figure 3.

Graphical spectra for 14. A, B and C are 1H, 13C and 11B NMR spectral data, respectively. The bigger peak in 11B spectrum corresponds to a BF3 etherate standard.

Figure 4.

Graphical 1H-1H COSY spectrum for 14.

3.3. Diarylbutene 17

A mixture of 1.8 μL 16 (13 μmol), 0.6 μL HBF4 (4.2 μmol) and 2.4 mg 1 (4.2 μmol) was dissolved in 0.6 mL acetonitrile-d3 in a sealed J-Young tube. The tube was then heated in a regulated oil bath at 100 °C for 18 h. The structure of 17 was determined based on NMR data and previously reported reference [37].

4. Conclusions

In sum, we present here evidence that 1-catalyzed oxidation of secondary alcohols is most likely to be happening through a mechanism that does not involve simultaneous participation of both boron and ruthenium in the way we originally proposed. This is supported by two key observations: (1) In a stoichiometric experiment wherein the requisite intermediate for a class (C) mechanism is prepared in isolation, it cannot be converted to the necessary product at an appreciable rate; (2) In a catalytic experiment, we see that the synthetic precursor to the proposed dual site catalyst is far more reactive in alcohol oxidation than the proposed catalyst itself. This reactivity shows that a pathway such as those shown in classes (B) and (C) are probably high energy relative to one that involves only the ruthenium active site.

Ongoing work in our lab involves mechanistic elucidation of reactions in which both a late metal and acidic site on the catalyst are involved, such as ammonia borane dehydrogenation with 1 [15] and the Shvo system [38,39], and new reaction development around a dual site catalyst motif.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the National Science Foundation (CHE-1054910) and the Hydrocarbon Research Foundation. We are grateful to the National Science Foundation (DBI-0821671, CHE-0840366), the National Institutes of Health (1 S10 RR25432), and the University of Southern California for their sponsorship of NMR spectrometers at USC. MB, AVF, and DG acknowledge fellowship support from the USC Undergraduate Research Associates Program.

References and Notes

- Shvo, Y.; Czarkie, D.; Rahamim, Y. A new group of ruthenium complexes: structure and catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 7400–7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyori, S.; Hashiguchi, S. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation catalyzed by chiral ruthenium complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 30, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu, N.; Fujii, A.; Hashiguchi, S.; Ikariya, T.; Noyori, R. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4916–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunanathan, C.; Ben-David, Y.; Milstein, D. Direct synthesis of amides from alcohols and amines with liberation of H2. Science 2007, 317, 790–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deno, N.C.; Peterson, H.J.; Saines, G.S. The hydride-transfer reaction. Chem. Rev. 1960, 60, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckvall, J.-E. Transition metal hydrides as active intermediates in hydrogen transfer reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 652, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bohle, D.S.; Li, C.-J. Cu-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling: a versatile strategy for C–C bond formations via the oxidative activation of sp3 C–H bonds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006, 103, 8928–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, B.L.; Williams, T.J. Dual site catalysts for hydride manipulations. Comments Inorg. Chem. 2012, 32, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, B.L.; Williams, T.J. Thermochemistry and molecular structure of a remarkable agostic interaction in a heterobifunctional ruthenium−boron complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1764–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, M.; Green, M.L.H.; Parkin, G. Coordination chemistry of saturated molecules special feature: agostic interactions in transition metal compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007, 104, 6908–6914. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, R.H. The organometallic chemistry of alkanes. Chem. Rev. 1985, 85, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.L.; Xu, Q. Catalytic hydrolysis of ammonia borane for chemical hydrogen storage. Catal. Today 2011, 170, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denney, M.C.; Pons, V.; Hebden, T.J.; Heinekey, D.M.; Goldberg, K.I. Efficient catalysis of ammonia borane dehydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12048–12049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, B.L.; Goldberg, K.I.; Heinekey, D.M.; Autrey, T.; Linehan, J.C. Iridium-catalyzed dehydrogenation of substituted amine boranes: kinetics, thermodynamics, and implications for hydrogen storage. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 8583–8585. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, B.L.; Guess, D.; Williams, T.J. A robust, air-stable, reusable ruthenium catalyst for dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14212–14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Vives, A.; Ujague, G.; Lledós, A. Hydrogen transfer to ketones catalyzed by Shvo's ruthenium hydride complex: a mechanistic insight. Organometallics 2007, 26, 4135–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I.; Rodríguez, M.; Sens, C.; Mola, J.; Kollipara, M.R.; Francàs, L.; Mas-Marza, E.; Escriche, L.; Llobet, A. Ru complexes that can catalytically oxidize water to molecular dioxygen. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Noyori, R.; Sandoval, C.A.; Muñiz, K.; Ohkuma, T. Metal–ligand bifunctional catalysis for asymmetric hydrogenation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2005, 363, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, B.L.; Pennington-Boggio, M.K.; Boz, E.; Williams, T.J. Discovery, applications, and catalytic mechanisms of Shvo’s catalyst. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2294–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvembu, R.; Prabhakaran, R.; Natarajan, K. Shvo’s diruthenium complex: a robust catalyst. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samec, J.S.M.; Bäckvall, J.-E.; Andersson, P.G.; Brandt, P. Mechanistic aspects of transition metal-catalyzed hydrogen transfer reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, C.P.; Guan, H. Cyclopentadienone iron alcohol complexes: synthesis, reactivity, and implications for the mechanism of iron-catalyzed hydrogenation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, Y.; Czarkie, D.; Rahamim, Y.; Shvo, Y. (Cyclopentadienone)ruthenium carbonyl complexes - a new class of homogeneous hydrogenation catalysts. Organometallics 1985, 4, 1459–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, C.P.; Beetner, S.E.; Johnson, J.B. Spectroscopic determination of hydrogenation rates and intermediates during carbonyl hydrogenation catalyzed by Shvo’s hydroxycyclopentadienyl diruthenium hydride agrees with kinetic modeling based on independently measured rates of elementary reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, C.P.; Singer, S.W.; Powell, D.R.; Hayashi, R.K.; Kavana, M. Hydrogen transfer to carbonyls and imines from a hydroxycyclopentadienyl ruthenium hydride: Evidence for concerted hydride and proton transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.L.S.; Beller, M.; Wang, G.-Z.; Bäckvall, J.-E. Ruthenium(II)-catalyzed oppenauer-type oxidation of secondary alcohols. Chem. Eur. J. 1996, 2, 1533–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.B.; Bäckvall, J.-E. Mechanism of ruthenium-catalyzed hydrogen transfer reactions. concerted transfer of OH and CH hydrogens from an alcohol to a (cyclopentadienone)ruthenium complex. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 7681–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, M.K.; Klinkel, K.L.; Wang, J.; Williams, T.J. Mechanism of hydride abstraction by cyclopentadienone-ligated carbonylmetal complexes (M = Ru, Fe). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda, K.; Mori, K.; Hara, T.; Mizugaki, T.; Ebitani, K. Design of hydroxyapatite-bound transition metal catalysts for environmentally-benign organic syntheses. Catal. Surv. Asia 2004, 8, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasri, K.; Rajaram, J.; Kuriacose, J.C. Ruthenium(III)-catalysed oxidation of secondary alcohols by N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMO). J. Mol. Cat. 1987, 333, 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, C.P.; Johnson, J.B.; Singer, S.W.; Cui, Q. Hydrogen elimination from a hydroxycyclopentadienyl ruthenium(II) hydride: Study of hydrogen activation in a ligand−metal bifunctional hydrogenation catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3100–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren-Selfridge, L.; Query, I.P.; Hanson, J.A.; Isley, N.A.; Guzei, I.A.; Clark, T.B. Synthesis of ruthenium boryl analogues of the Shvo metal−ligand bifunctional catalyst. Organometallics 2010, 29, 3896–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren-Selfridge, L.; Londino, H.N.; Vellucci, J.K.; Simmons, B.L.; Casey, C.P.; Clark, T.B. A boron-substituted analogue of the Shvo hydrogenation catalyst: catalytic hydroboration of aldehydes, imines, and ketones. Organometallics 2009, 28, 2085–2090. [Google Scholar]

- CCDC 738031 and 738030 contain supplementary crystallographic data for compounds 8 and 1 respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Available online: http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- Martín-Mature, B.; Åberg, J.B.; Edin, M.; Bäckvall, J.-E. Racemization of secondary alcohols catalyzed by cyclopentadienylruthenium complexes: Evidence for an alkoxide pathway by fast β-hydride elimination–readdition. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 6063–6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, I.; Masakatsu, S. Bifunctional Molecular Catalysis, 1st ed; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.N.; Sarma, K; Pathak, M.G.; Goswami, A. Silica-supported KHSO4: an efficient system for activation of aromatic terminal olefins. Synlett 2010, 2908–2912. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, B.L.; Williams, T.J. Dehydrogenation of ammonia-borane by Shvo’s catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2010, 4815–4817. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Conley, B.L.; Williams, T.J. A three-Stage mechanistic model for ammonia–borane dehydrogenation by Shvo’s catalyst. Organometallics. 2012, 31. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).