Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Supported and Bulk Ni Catalysts for Hydrogen Production

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Catalyst Properties

2.1.1. Physical Properties (N2 Adsorption-Desorption)

2.1.2. Catalyst Reducibility (Temperature Programmed Reduction (TPR))

2.1.3. Crystalline Structure (X-ray Diffraction (XRD))

2.2. Performance of the Catalysts

2.2.1. Supported Catalysts

2.2.2. Bulk Catalysts

2.3. Analysis of Coke Deposition (Temperature Programmed Oxidation (TPO))

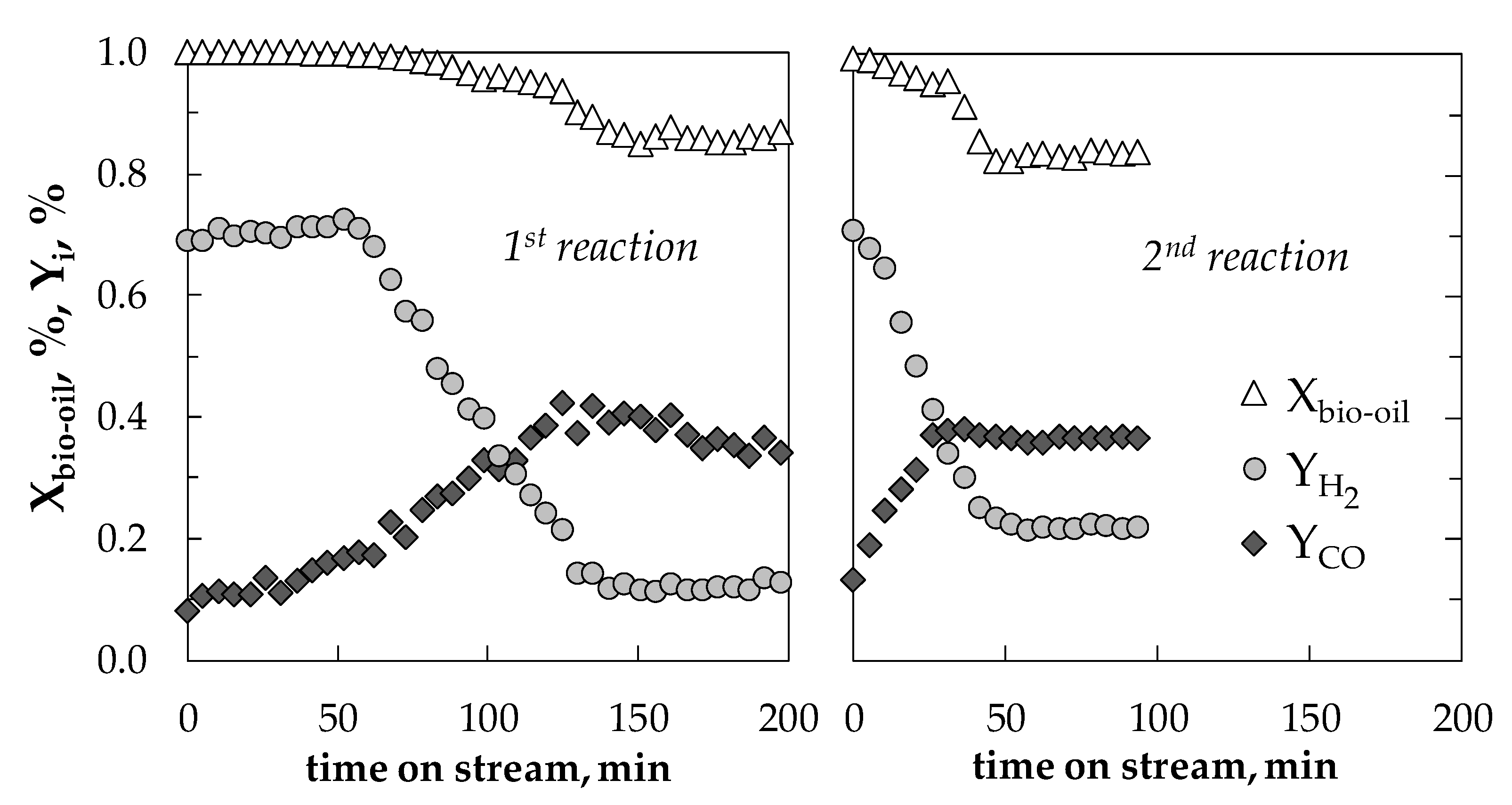

2.4. Regenerability of the Catalyst

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bio-Oil Production and Properties

4.2. Synthesis and Characterization of the Catalysts

4.3. Reaction Equipment, Experimental Conditions, and Reaction Indices

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sgobbi, A.; Nijs, W.; De Miglio, R.; Chiodi, A.; Gargiulo, M.; Thiel, C. How far away is hydrogen? Its role in the medium and long-term decarbonisation of the European energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, E.S.; Deane, J.P.; Ó Gallachóir, B.P. The role of hydrogen in low carbon energy futures—A review of existing perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 82, 3027–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politano, A.; Cattelan, M.; Boukhvalov, D.W.; Campi, D.; Cupolillo, A.; Agnoli, S.; Apostol, N.G.; Lacovig, P.; Lizzit, S.; Farías, D.; et al. Unveiling the Mechanisms Leading to H2 Production Promoted by Water Decomposition on Epitaxial Graphene at Room Temperature. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 4543–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; He, L. Towards an efficient hydrogen production from biomass: A review of processes and materials. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 490–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arregi, A.; Amutio, M.; Lopez, G.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Evaluation of thermochemical routes for hydrogen production from biomass: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 165, 696–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattahathan, S.A.; Adhikari, A.; Abdoulmoumine, N. A review on current status of hydrogen production from bio-oil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2366–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Brown, T.R.; Hu, G.; Brown, R.C. Comparative techno-economic analysis of biohydrogen production via bio-oil gasification and bio-oil reforming. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 51, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y. Catalysts for steam reforming of bio-oil: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 56, 4627–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, D.; van de Beld, B.; Bridgwater, A.V.; Elliott, D.C.; Oasmaa, A.; Preto, F. State-of-the-art of fast pyrolysis in IEA bioenergy member countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 20, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oasmaa, A.; Fonts, I.; Pelaez-Samaniego, M.R.; Garcia-Perez, M.E.; Garcia-Perez, M. Pyrolysis oil multiphase behavior and phase stability: A review. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 6179–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermoso, J.; Pizarro, P.; Coronado, J.M.; Serrano, D.P. Advanced biofuels production by upgrading of pyrolysis bio-oil. WIREs Energy Environ. 2017, 6, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Remiro, A.; Garcia-Gomez, N.; Gayubo, A.G.; Bilbao, J. Recent research progress on bio-oil conversion into bio-fuels and raw chemicals: A review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tao, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, B.; Li, W.; Li, X. Hydrogen production via acetic acid steam reforming: A critical review on catalysts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2107, 79, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabgan, W.; Abdullah, T.A.T.; Mat, R.; Nabgan, B.; Gambo, Y.; Ibrahim, M.; Ahmad, A.; Jalil, A.A.; Triwahyono, S.; Saeh, I. Renewable hydrogen production from bio-oil derivative via catalytic steam reforming: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, A.; Arandia, A.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Comparison of Ni based and Rh based catalyst performance in the oxidative steam reforming of raw bio-oil. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 7147–7156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, V.; Akdim, O.; Provendier, H.; Mirodatos, C. Ethanol oxidative steam reforming over Ni-based catalysts. J. Power Sources 2005, 145, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graschinsky, C.; Lupiano-Contreras, J.; Amadeo, N.; Laborde, M. Ethanol oxidative steam reforming over Rh(1%)MgAl2O4Al2O3 catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 15348–15356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoplyak, O.; Barteau, M.A.; Chen, J.G. Comparison of H2 production from ethanol and ethylene glycol on M/Pt(111) (M = Ni, Fe, Ti) bimetallic surfaces. Catal. Today 2009, 147, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernik, S.; French, R. Distributed production of hydrogen by auto-thermal reforming of fast pyrolysis bio-oil. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasikallio, V.; Azhari, A.; Kihlman, J.; Simell, P.; Lehtonen, J. Oxidative steam reforming of pyrolysis oil aqueous fraction with zirconia pre-conversion catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 12088–12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, A.; Arandia, A.; Oar-Arteta, L.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Stability of a Rh/CeO2-ZrO2 catalyst in the oxidative steam reforming of raw bio-oil. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 3588–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, A. Catalyst and Conditions in the Oxidative Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Stable H2 Production. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Politano, A.; Chiarello, G. Vibrational investigation of catalyst surface: Change of the adsorption site of CO molecules upon coadsorption. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 13541–13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, A.; Valle, B.; Aguayo, A.T.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Steam reforming of raw bio-oil in a fluidized bed reactor with prior separation of pyrolytic lignin. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 7549–7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Aramburu, B.; Remiro, A.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Effect of calcination/reduction conditions of Ni/La2O3-Al2O3 catalyst on its activity and stability for hydrogen production by steam reforming of raw bio-oil/ethanol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 147, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Aramburu, B.; Benito, P.L.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Biomass to hydrogen-rich gas via steam reforming of raw bio-oil over Ni/La2O3-αAl2O3 catalyst: Effect of space-time and steam-to-carbon ratio. Fuel 2018, 216, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Aramburu, B.; Olazar, M.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Steam reforming of raw bio-oil over Ni/La2O3-αAl2O3: Influence of temperature on product yields and catalyst deactivation. Fuel 2018, 216, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hill, M.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Z. Highly efficient Ni/CeO2 catalyst for the liquid phase hydrogenation of maleic anhydride. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014, 488, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Kunzru, D. Steam reforming of ethanol for production of hydrogen over Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 catalyst: Effect of support and metal loading. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebiad, M.A.; El-Hafiz, D.R.A.; Elsalamony, R.A.; Mohamed, L.S. Ni supported high surface area CeO2-ZrO2 catalysts for hydrogen production from ethanol steam reforming. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 8145–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, G.; Laggazo, A.; Riani, P.; Busca, G. Steam reforming of ethanol-phenol mixture on Ni/Al2O3: Effect of Ni loading and sulphur deactivation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rida, K.; Peña, M.A.; Sastre, E.; Martínez-Arias, A. Effect of calcination temperature on structural properties and catalytic activity in oxidation reactions of LaNiO3 perovskite prepared by Pechini method. J. Rare Earths 2012, 30, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Zubenko, D.; Rosen, B.A. Influence of LaNiO3 shape on its solid-phase crystallization into coke-free reforming catalysts. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4199–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.F.; Dias, J.A.C.; Maciel, C.G.; Assaf, J.M. Ni/Al2O3 catalysts: Effects of the promoters Ce, La and Zr on the methane steam and oxidative reforming reactions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.Y.; Tu, J.y.; Wang, T.J.; Ma, L.L.; Wang, C.G.; Chen, L.G. Bio-syngas methanation towards synthetic natural gas (SNG) over highly active Al2O3–CeO2 supported Ni catalyst. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 134, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khateria, S.; Gupta, A.; Deo, G.; Kunzru, D. Effect of calcination temperature on stability and activity of Ni/MgAl2O4 catalyst for steam reforming of methane at high pressure condition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 14123–14132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, S.; Shimizu, T.; Kameyama, H.; Haneda, T.; Kikuchi, R. Ni/CeO2 catalysts with high CO2 methanation activity and high CH4 selectivity at low temperatures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 5527–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado, J.P.; Alvarez, R.; Munuera, G. Study of CeO2 XPS spectra by factor analysis: Reduction of CeO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2000, 161, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Delacruz, V.M.; Ternero, F.; Pereñiguez, R.; Caballero, A.; Holgado, J.P. Study of nanostructured Ni/CeO2 catalysts prepared by combustion synthesis in dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 384, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpanich, S.; Meeyoo, V.; Rirksomboon, T. Methane partial oxidation over Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 mixed oxide solid solution catalysts. Catal. Today 2004, 93–95, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, H.S.; Koo, K.Y.; Yoon, W.L. Combined reforming of methane over co-precipitated Ni-CeO2, Ni-ZrO2 and Ni-Ce0.8Zr0.2O2 catalysts to produce synthesis gas for gas to liquid (GTL) process. Catal. Today 2009, 146, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Comparative study of LaNiO3 and La2NiO4 catalysts for partial oxidation of methane. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2008, 95, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneerung, T.; Hidajat, K.; Kawi, S. LaNiO3 perovskite catalyst precursor for rapid decomposition of methane: Influence of temperature and presence of H2 in feed stream. Catal. Today 2011, 171, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.H.; Wang, C.B.; Chien, S.H. Catalytic performance of steam reforming of ethanol at low temperature over LaNiO3 perovskite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 3226–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, G.R.; Rahmanzadeh, M.; Khosravian, F. The effects of partial substitution of Ni by Zn in LaNiO3 perovskite catalyst for methane dry reforming. J. CO2 Util. 2014, 6, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.S.; Au, C.T. Carbon deposition and catalyst stability over La2NiO4/γ-Al2O3 during CO2 reforming of methane to syngas. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 244, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yu, B.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. A single layer solid oxide fuel cell composed of La2NiO4 and doped ceria-carbonate with H2 and methanol as fuels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 9059–9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, M.L.; Laberty-Robert, C.; Ansart, F.; Tailhades, P. Elaboration and characterization of La2NiO4+δ powders and thin films via a modified sol–gel process. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.S.; Mondragón, F.; Tatibouët, J.M.; Barrault, J.; Batiot-Dupeyrat, C. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over La2NiO4 as catalyst precursor-Characterization of carbon deposition. Catal. Today 2008, 133–135, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benrabaa, R.; Barama, A.; Boukhlouf, H.; Guerrero-Caballero, J.; Rubbens, A.; Bordes-Richard, E.; Löfberg, A.; Vannier, R.N. Physico-chemical properties and syngas production via dry reforming of methane over NiAl2O4 catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 12989–12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, C.; Idriss, H.; Kiennemann, A. Hydrogen production by ethanol reforming over Rh/CeO2-ZrO2 catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2002, 3, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varez, A.; Garcia-Gonzalez, E.; Sanz, J. Cation miscibility in CeO2-ZrO2 oxides with fluorite structure. A combined TEM, SAED and XRD Rietveld analysis. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 4249–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, L.H.; Reddy, G.K.; Devaiah, D.; Reddy, B.M. A rapid microwave-assisted solution combustion synthesis of CuO promoted CeO2-MxOy (M = Zr, La, Pr and Sm) catalysts for CO oxidation. Appl Catal A Gen. 2012, 445−446, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhan, W.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, G. Preparation of high oxygen storage capacity and thermally stable ceria–zirconia solid solution. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ochoa, A.; Barbarias, I.; Artetxe, M.; Gayubo, A.G.; Olazar, M.; Bilbo, J.; Castaño, P. Deactivation dynamics of a Ni supported catalyst during the steam reforming of volatiles from waste polyethylene pyrolysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 209, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wu, Z.; Chang, X.; Jin, W.; Xu, N. One-step synthesis and characterization of La2NiO4+δ mixed-conductive oxide for oxygen permeation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 6910–6915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Guo, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Effect of La2O3 promoter on NiO/Al2O3 catalyst in CO methanation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 31, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Guan, Y.; Liu, Y. Ni nanoparticles highly dispersed on ZrO2 and modified with La2O3 for CO methanation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 12699–12707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Prasad, R. An Overview on dry reforming of methane: Strategies to reduce carbonaceous deactivation of catalysts. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 108668–108688. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Li, X.; Gong, J. Catalytic reforming of oxygenates: State of the art and future prospects. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11529–11653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa, A.; Aramburu, B.; Valle, B.; Resasco, D.E.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G.; Castaño, P. Role of oxygenates and effect of operating conditions in the deactivation of a Ni supported catalyst during the steam reforming of bio-oil. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 4315–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zou, J.; Shi, X.; Rukundo, P.; Wang, Z.J. A Ni/CeO2-CDC-SiC catalyst with improved coke resistance in CO2 reforming of methane. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2330–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidian, T.; Guilhaume, N.; Iojoiu, E.; Provendier, H.; Mirodatos, C. Hydrogen production from crude pyrolysis oil by a sequential catalytic process. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 73, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liu, R. Sustainable hydrogen production from steam reforming of bio-oil model compound based on carbon deposition/elimination. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2860–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lónyi, F.; Valyon, J.; Someus, E.; Hancsók, J. Steam reforming of bio-oil from pyrolysis of MBM over particulate and monolith supported Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalysts. Fuel 2013, 112, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, A.; Arandia, A.; Oar-Arteta, L.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Regeneration of NiAl2O4 spinel type catalysts used in the reforming of raw bio-oil. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 237, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberton, A.L.; Souza, M.; Schmal, M. Carbon formation and its influence on ethanol steam reforming over Ni/Al2O3 catalysts. Catal. Today 2007, 123, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D.; Balbuena, P. Characterization of carbon atomistic pathways during single-walled carbon nanotube growth on supported metal nanoparticles. Carbon 2013, 57, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamskar, F.R.; Rezaei, M.; Meshkani, F. The influence of Ni loading on the activity and coke formation of ultrasound-assisted co-precipitated Ni-Al2O3 nanocatalyst in dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 4155–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanksale, A.; Zhou, C.H.; Beltramini, J.N.; Lu, G.Q. Hydrogen production by aqueous phase reforming of sorbitol using bimetallic Ni–Pt catalysts: Metal support interaction. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2009, 65, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Choong, C.K.S.; Zhong, Z.; Huanf, L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, J. Support and alloy effects on activity and product selectivity for ethanol steam reforming over supported nickel cobalt catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 16321–16332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.J.; Xia, G.F.; Li, M.F.; Wu, Y.; Nie, H.; Li, D.D. Effect of support on the performance of Ni-based catalyst in methane dry reforming. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2015, 43, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Arregui, A.; Amutio, M.; Gayubo, A.G.; Olazar, M.; Bilbao, J.; Castaño, P. Coking and sintering progress of a Ni supported catalyst in the steam reforming of biomass pyrolysis volatiles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 233, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Remiro, A.; Aguayo, A.T.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Catalysts of Ni/α-Al2O3 and Ni/La2O3-αAl2O3 for hydrogen production by steam reforming of bio-oil aqueous fraction with pyrolytic lignin retention. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, H.S.; Potdar, H.S.; Jun, K.W. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over co-precipitated Ni-CeO2, Ni-ZrO2 and Ni-Ce-ZrO2 catalysts. Catal. Today 2004, 93–95, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, A.; Remiro, A.; Valle, B.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Operating strategies for the oxidative steam reforming (OSR) of raw bio-oil in a continuous two-step system. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 57, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

| Catalyst Supports | SBET, m2 g−1 | Vpore, cm3 g−1 | dpore, nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| αAl2O3 (Al) | 50.0 | 0.205 | 8.2 |

| La2O3-αAl2O3 (LaAl) | 41.4 | 0.154 | 14.5 |

| CeO2 (Ce) | 191.8 | 0.417 | 8.8 |

| CeO2-ZrO2 (CeZr) | 47.6 | 0.121 | 7.9 |

| Synthetized Catalysts | |||

| Ni/LaAl | 37.6 | 0.145 | 14.6 |

| Ni/Ce | 159.2 | 0.312 | 8.2 |

| 5Ni/CeZr | 31.6 | 0.133 | 10.2 |

| 15Ni/CeZr | 23.2 | 0.116 | 10.4 |

| Commercial Catalyst | |||

| G90 | 19.0 | 0.041 | 12.2 |

| Catalyst | SBET, m2 g−1 | Vpore, cm3 g−1 | dpore, nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| LaNiO3 | 9.2 | 0.068 | 29.5 |

| La2NiO4 | 7.3 | 0.012 | 6.8 |

| NiAl2O4 | 96.8 | 0.120 | 5.0 |

| Catalyst | dNi0, nm (44.5°) Plane (1 1 1) | dNi0, nm (51.8°) Plane (2 0 0) |

|---|---|---|

| Supported catalysts | ||

| Ni/LaAl | 8.7 | 7.6 |

| Ni/Ce | 23.4 | 20.5 |

| 5Ni/CeZr | 21.4 | - |

| 15Ni/CeZr | 34.2 | 30.7 |

| G90* [59] | 24.0 | - |

| Bulk Catalysts | ||

| LaNiO3 | 14.2 | - |

| La2NiO4 | 11.6 | - |

| NiAl2O4 | 17.5 | 13.0 |

| Catalyst | Name | Nominal Ni Content, wt % | TC, °C | TR, °C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supported | Ni/La2O3-αAl2O3 | Ni/LaAl | 10% Ni | 550 | 700 |

| Ni/CeO2 | Ni/Ce | 15% Ni | 550 | 700 | |

| Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 | 5Ni/CeZr 15Ni/CeZr | 5% Ni 15% Ni | 550 | 700 | |

| Bulk | NiAl2O4 spinel | NiAl2O4 | 33% Ni | 850 | 850 |

| LaNiO3 perovskite | LaNiO3 | 23.9% Ni | 700 | 700 | |

| La2NiO4 perovskite | La2NiO4 | 14.6% Ni | |||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arandia, A.; Remiro, A.; García, V.; Castaño, P.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Supported and Bulk Ni Catalysts for Hydrogen Production. Catalysts 2018, 8, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080322

Arandia A, Remiro A, García V, Castaño P, Bilbao J, Gayubo AG. Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Supported and Bulk Ni Catalysts for Hydrogen Production. Catalysts. 2018; 8(8):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080322

Chicago/Turabian StyleArandia, Aitor, Aingeru Remiro, Verónica García, Pedro Castaño, Javier Bilbao, and Ana G. Gayubo. 2018. "Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Supported and Bulk Ni Catalysts for Hydrogen Production" Catalysts 8, no. 8: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8080322