Surface Modification Design for Improving the Strength and Water Vapor Permeability of Waterborne Polymer/SiO2 Composites: Molecular Simulation and Experimental Analyses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of SiO2 Nanoparticles and Modified-SiO2 Nanoparticles

2.3. Preparation of PMA/Modified-SiO2 Nanocomposite and its Composite Film

2.4. Characterization and Measurements

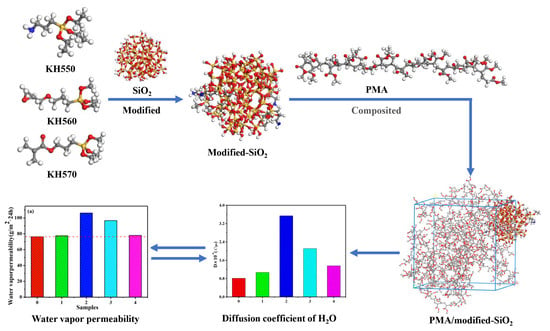

2.5. Simulation Methodologies

2.5.1. Construction of SiO2 Nanoparticles

2.5.2. Construct the Composite System Model

2.5.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Process

3. Results

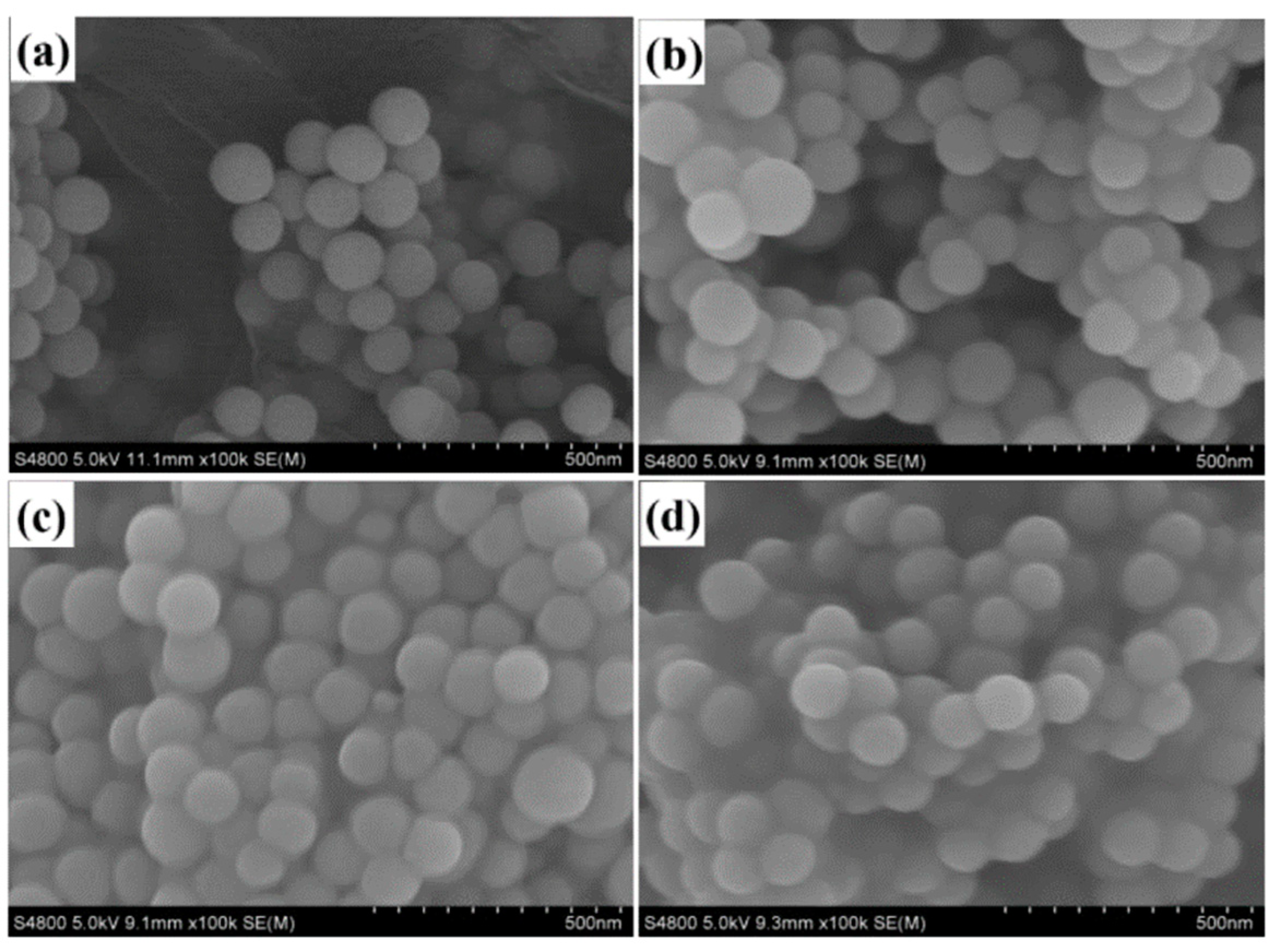

3.1. Morphological and Structural Characterization of Modified-SiO2

3.2. Morphological and Structural Characterization of PMA/SiO2 Composite Emulsion and Film

3.3. Properties of PMA/SiO2 and PMA/Modified-SiO2 Composite Films

3.3.1. Mechanical Properties of PMA/SiO2 and PMA/Modified-SiO2 Composite Films

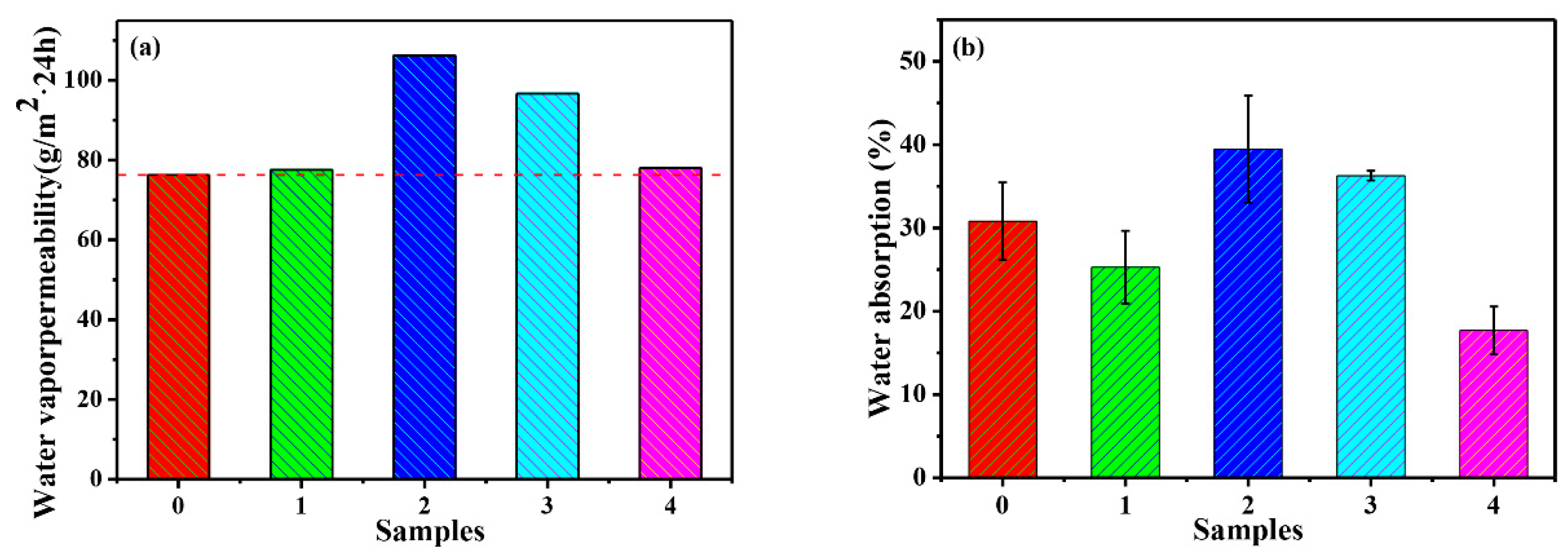

3.3.2. Water Vapor Permeability of PMA/SiO2 and PMA/Modified-SiO2 Composite Films

3.3.3. Water Resistance of PMA/SiO2 and PMA/Modified-SiO2 Composite Films

3.3.4. Thermal Properties of PMA/SiO2 Composite Films

3.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.4.1. Binding Energy Analysis

3.4.2. MSD (Mean Square Displacement) and Diffusion Coefficient (D) of Water in Composite System

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.; Ji, H.; Zhu, K.; Jing, W.; Qiu, J. Dramatically improved piezoelectric properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride) composites by incorporating aligned TiO2 @MWCNTs. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 123, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Hsu, J.H.; Yi, S.I.; Kim, S.L.; Choi, K.; Yang, G.; Yu, C. Thermally Driven Large N-Type Voltage Responses from Hybrids of Carbon Nanotubes and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) with Tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene. Adv. Mater. 2016, 27, 6855–6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, H.B.; Yang, Y.; Mu, W.; Cao, A.; Yu, Z.Z. High-Performance Epoxy Nanocomposites Reinforced with Three-Dimensional Carbon Nanotube Sponge for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, G.; Tao, W.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Tailoring the dispersion of nanoparticles and the mechanical behavior of polymer nanocomposites by designing the chain architecture. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 32024–32037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shojaeiarani, J.; Bajwa, D.; Stark, N.M. Spin-coating: A new approach for improving dispersion of cellulose nanocrystals and mechanical properties of poly (lactic acid) composites. Carbohyd. Polym. 2018, 190, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Xu, M.; Hai, P.; Ren, D.; Li, K.; Liu, X. Secondary dispersion of BaTiO3 for the enhanced mechanical properties of the Poly (arylene ether nitrile)-based composite laminates. Polym. Test. 2018, 66, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, Y.; Kakroodi, A.R.; Ameli, A.; Filleter, T.; Park, C.B. Highly stretchable conductive thermoplastic vulcanizate/carbon nanotube nanocomposites with segregated structure, low percolation threshold and improved cyclic electromechanical performance. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmand, M.; Sadeghi, S.; Khajehpour, M.; Sundararaj, U. Carbon nanotube/graphene nanoribbon/polyvinylidene fluoride hybrid nanocomposites: Rheological and dielectric properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 121, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Zang, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Du, Y.; Cheetham, A.K.; Wang, J. 2D carbide nanomeshes and their assembling into 3D microflowers for efficient water splitting. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 243, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Huang, T.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Gao, S.; Chen, M.; Wu, L. Hierarchical Macro–Mesoporous Polymeric Carbon Nitride Microspheres with Narrow Bandgap for Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1801241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senses, E.; Akcora, P. An Interface-Driven Stiffening Mechanism in Polymer Nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1868–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Han, C.R.; Duan, J.F.; Xu, F.; Sun, R.C. Interaction of Silica Nanoparticle/Polymer Nanocomposite Cluster Network Structure: Revisiting the Reinforcement Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 8223–8230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcu, C.; Purcar, V.; Spătaru, C.; Alexandrescu, E.; Şomoghi, R.; Trică, B.; Niţu, S.; Panaitescu, D.; Dan, D.; Jecu, M.L. The Influence of New Hydrophobic Silica Nanoparticles on the Surface Properties of the Films Obtained from Bilayer Hybrids. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabzi, M.; Mirabedini, S.M.; Zohuriaan-Mehr, J.; Atai, M. Surface modification of TiO2 nano-particles with silane coupling agent and investigation of its effect on the properties of polyurethane composite coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2009, 65, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Jouault, N.; Benicewicz, B.; Neely, T. Nanocomposites with Polymer Grafted Nanoparticles. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 3199–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, S.; He, G. High dimensional stability and low viscous response solid propellant binder based on graphene oxide nanosheets and dual cross-linked polyurethane. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 161, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Sun, Y.; He, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Luo, Y.; Liu, F. Enhancing mechanical properties of styrene-butadiene rubber/silica nanocomposites by in situ interfacial modification with a novel rare-earth complex. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 87, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Bai, S. Three-dimensional graphene foam-filled elastomer composites with high thermal and mechanical properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017, 9, 26447–26459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Meng, G.; Chen, Z.; Qiu, H.L.; Liu, X. Grafting photosensitive polyurethane onto colloidal silica for use in UV-curing polyurethane nanocomposites. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 443, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Shu, Y.; Ye, L. In situ crosslinking of poly (vinyl alcohol)/graphene oxide-glutamic acid nano-composite hydrogel as microbial carrier: Intercalation structure and its wastewater treatment performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 336, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Wan, Q.; Tian, J.; Huang, L.; Jiang, R.; Deng, F.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Marrying the mussel inspired chemistry and Kabachnik-Fields reaction for preparation of SiO2 polymer composites and enhancement removal of methylene blue. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 422, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, A.; Gan, F. Improvement of polyacrylate coating by filling modified nano-TiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 8635–8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zeng, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Preparation and characterization of nano-SiO2/fluorinated polyacrylate composite latex via nano-SiO2/acrylate dispersion. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2012, 396, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Rui, C.; Lyu, B.; Ma, J.; Duan, X. Preparation of epoxy-acrylate copolymer/nano-silica via Pickering emulsion polymerization and its application as printing binder. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Shi, C.; Ma, J.; Bing, W.; Zhang, Y. Double in-situ synthesis of polyacrylate/nano-TiO2 composite latex. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 85, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Chang, R.; Lyu, B.; Ma, J. Growth from spherical to rod-like SiO2: Impact on microstructure and performance of nanocomposite. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 151814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Chang, R.; Lyu, B.; Ma, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Q. Synthesis of raspberry-like SiO2/polyacrylate nanocomposite latexes via a one-step miniemulsion polymerization and its film properties. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z. Polyacrylate/silica nanocomposite materials prepared by sol–gel process. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 4169–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Shi, C.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J.; Sha, R. Effect of hollow silica spheres on water vapor permeability of polyacrylate film. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 11485–11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Cui, F. Molecular dynamics simulations of interfacial interactions between small nanoparticles during diffusion-limited aggregation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 357, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussou, R.; Karatasos, K. Graphene/poly(ethylene glycol) nanocomposites as studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Mater. Des. 2016, 97, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M. A molecular dynamic simulation method to elucidate the interaction mechanism of nano-SiO2 in polymer blends. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 12889–12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Arjmand, M.; Otero Navas, I.; Zehtab Yazdi, A.; Sundararaj, U. Effect of nanofiller geometry on network formation in polymeric nanocomposites: Comparison of rheological and electrical properties of multiwalled carbon nanotube and graphene nanoribbon. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3954–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneie, A.; Schuschnigg, S.; Holzer, C. Dissipative Particle Dynamics Models of Orientation of Weakly-Interacting Anisometric Silicate Particles in Polymer Melts under Shear Flow: Comparison with the Standard Orientation Models. Macromol. Theor. Simul. 2016, 25, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneie, A.; Hufenus, R. Hybrid carbon nanoparticles in polymer matrix for efficient connected networks: Self-assembly and continuous pathways. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 3547–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidian, M.; Grimaldi, C.; Forró, L.; Magrez, A. Role of the particle size polydispersity in the electrical conductivity of carbon nanotube-epoxy composites. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujishiro, S.; Kan, K.; Akashi, M.; Ajiro, H. Stability of adhesive interfaces by stereocomplex formation of polylactides and hybridization with nanoparticles. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 141, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanou, N.A.; Power, J.A.; Harmandaris, V. Structural and Dynamical Properties of Polyethylene/Graphene Nanocomposites through Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Polymers 2015, 7, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, P. Study of the glass transition temperature and the mechanical properties of PET/modified silica nanocomposite by molecular dynamics simulation. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Bai, S.; Ren, Y.; Liu, C.; Simion, D.; Qin, J. π-π stacking interface design for improving the strength and electromagnetic interference shielding of ultrathin and flexible water-borne polymer/sulfonated graphene composite. Carbon 2019, 149, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Yan, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, X. Molecular dynamics simulations on the interaction between microsphere and water in nanosilica/crosslinked polyacrylamide microsphere aqueous solution with a core–shell structure and its swelling behavior. Compos. Interface 2017, 25, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Yan, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, X. Molecular dynamic simulation of core–shell structure: Study of the interaction between modified surface of nano-SiO2 and PAMAA in vacuum and aqueous solution. Compos. Interface 2017, 24, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenero, J.; Alvarez, F.; Arbe, A. Self-motion and the alpha relaxation in a simulated glass-forming polymer: Crossover from Gaussian to non-Gaussian dynamic behavior. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter. Phys. 2002, 65, 41804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basconi, J.E.; Shirts, M.R. Effects of Temperature Control Algorithms on Transport Properties and Kinetics in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 2887–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, J.; Ahmadi, M. Molecular dynamics simulation of elastic properties of CuPd nanowire. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fabiani, I.; Koh, M.L.; Dalmas, F.; Elidottir, K.L.; Hinder, S.J.; Jurewicz, I.; Lansalot, M.; Bourgeat-Lami, E.; Keddie, J.L. Design of waterborne nanoceria/polymer nanocomposite UV-absorbing coatings: Pickering versus blended particles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 3956–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, M.; Sun, S.; Ma, J.; Li, C. Effect of Surface Structure of Nano-CaCO3 Particles on Mechanical and Rheological Properties of PVC Composites. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 2010, 49, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, H.E.H.; Govaert, L.E. Mechanical performance of polymer systems: The relation between structure and properties. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2005, 30, 915–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancar, J.; Kucera, J. Yield behavior of polypropylene filled with CaCO3 and Mg(OH)2. I. ‘Zero’ interfacial adhesion. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2004, 30, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Sun, J.W.; Hu, Y.; Kan, C.Y. Polysiloxane/polyacrylate composite latexes with balanced mechanical property and breathability: Effect of core/shell mass ratio. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Yang, Y.; Ma, J. Fabrication of monodisperse hollow silica spheres and effect on water vapor permeability of polyacrylate membrane. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 407, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu, Y.; Ruan, K.; Qiu, H.; Lu, Y.; Liang, C.; Kong, J.; Gu, J. Fabrication and investigation on the PANI/MWCNT/thermally annealed graphene aerogel/epoxy electromagnetic interference shielding nanocomposites. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 121, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tang, L.; Guo, Y.; Liang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Kou, K.; Gu, J. Improvement of thermal conductivities for PPS dielectric nanocomposites via incorporating NH2-POSS functionalized nBN fillers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 101, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S. Molecular dynamics simulations and microscopic analysis of the damping performance of hindered phenol AO-60/nitrile-butadiene rubber composites. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 6719–6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravanian, A.; Dehghani, M.; Pazirofteh, M.; Asghari, M.; Mohammadi, A.H.; Shahsavari, D. Grand canonical Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations of the structural properties, diffusion and adsorption of hydrogen molecules through poly (benzimidazoles)/nanoparticle oxides composites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2803–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Weight Loss Temperature (°C) | Heat-Resistance Index a (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T5 | T30 | ||

| 0 | 318.43 | 375.43 | 172.79 |

| 1 | 325.42 | 374.92 | 174.01 |

| 2 | 327.88 | 375.88 | 174.77 |

| 3 | 332.99 | 374.49 | 175.37 |

| 4 | 329.98 | 376.98 | 175.51 |

| Systems | Etotal (kcal/mol) | EPMA (kcal/mol) | ESiO2 (or Emodified-SiO2) (kcal/mol) | Einter (kcal/mol) | Ebinding (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA | 10,043.97 | 10,043.97 | - | - | - |

| PMA/SiO2 | −1812.38 | 12,722.97 | −14,260.52 | −274.83 | 274.83 |

| PMA/KH550-SiO2 | −2323.97 | 12,545.98 | −14,552.63 | −317.32 | 317.32 |

| PMA/KH560-SiO2 | −381.20 | 13,785.56 | −13,810.49 | −356.27 | 356.27 |

| PMA/KH570-SiO2 | −1646.98 | - | - | - | - |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, H. Surface Modification Design for Improving the Strength and Water Vapor Permeability of Waterborne Polymer/SiO2 Composites: Molecular Simulation and Experimental Analyses. Polymers 2020, 12, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010170

Wu Y, Ma J, Liu C, Yan H. Surface Modification Design for Improving the Strength and Water Vapor Permeability of Waterborne Polymer/SiO2 Composites: Molecular Simulation and Experimental Analyses. Polymers. 2020; 12(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yingke, Jianzhong Ma, Chao Liu, and Hongxia Yan. 2020. "Surface Modification Design for Improving the Strength and Water Vapor Permeability of Waterborne Polymer/SiO2 Composites: Molecular Simulation and Experimental Analyses" Polymers 12, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010170