Selective Controlled/Living Photoradical Polymerization of Glycidyl Methacrylate, Using a Nitroxide Mediator in the Presence of a Photosensitive Triarylsulfonium Salt

Abstract

:1. Introduction

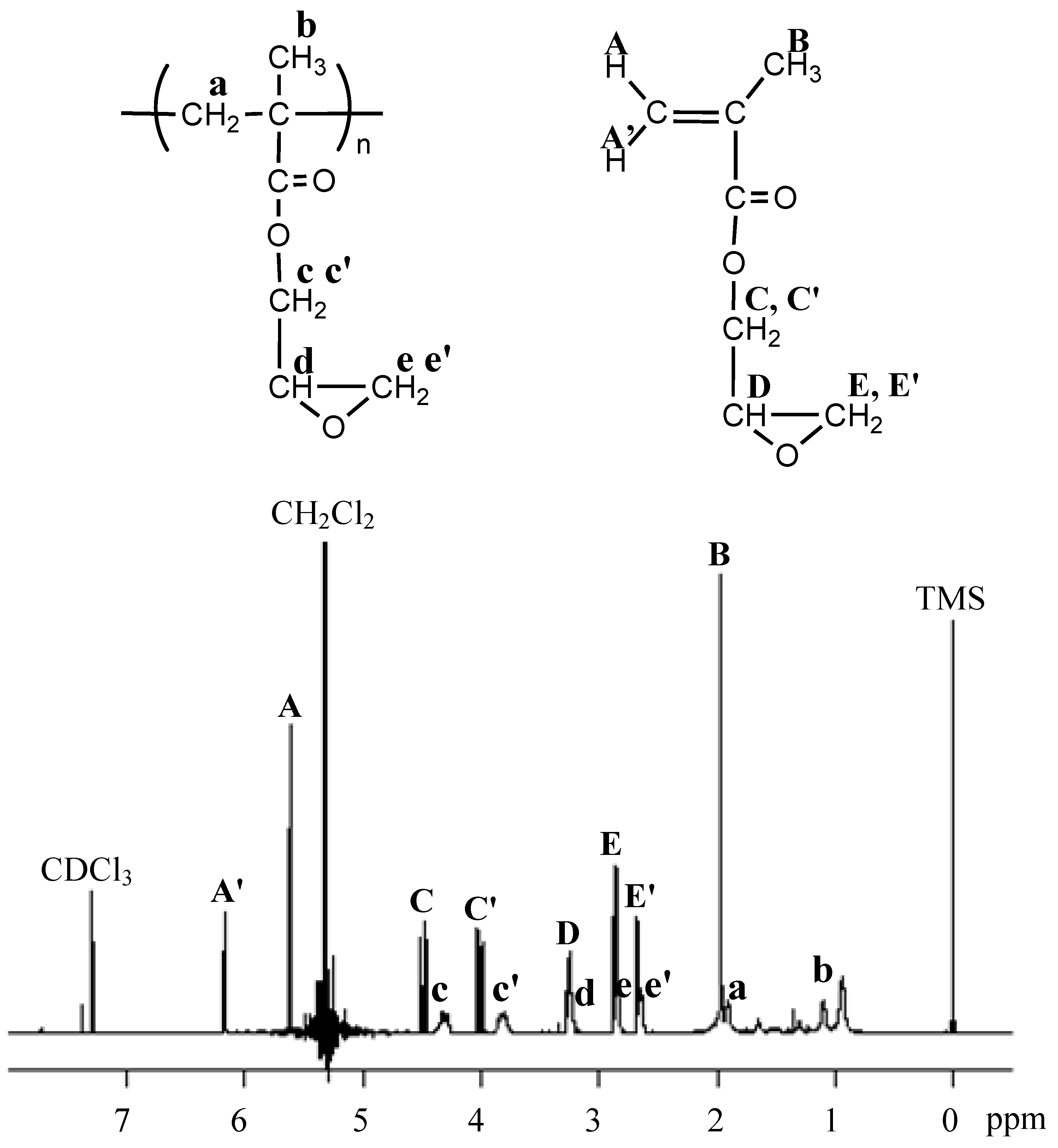

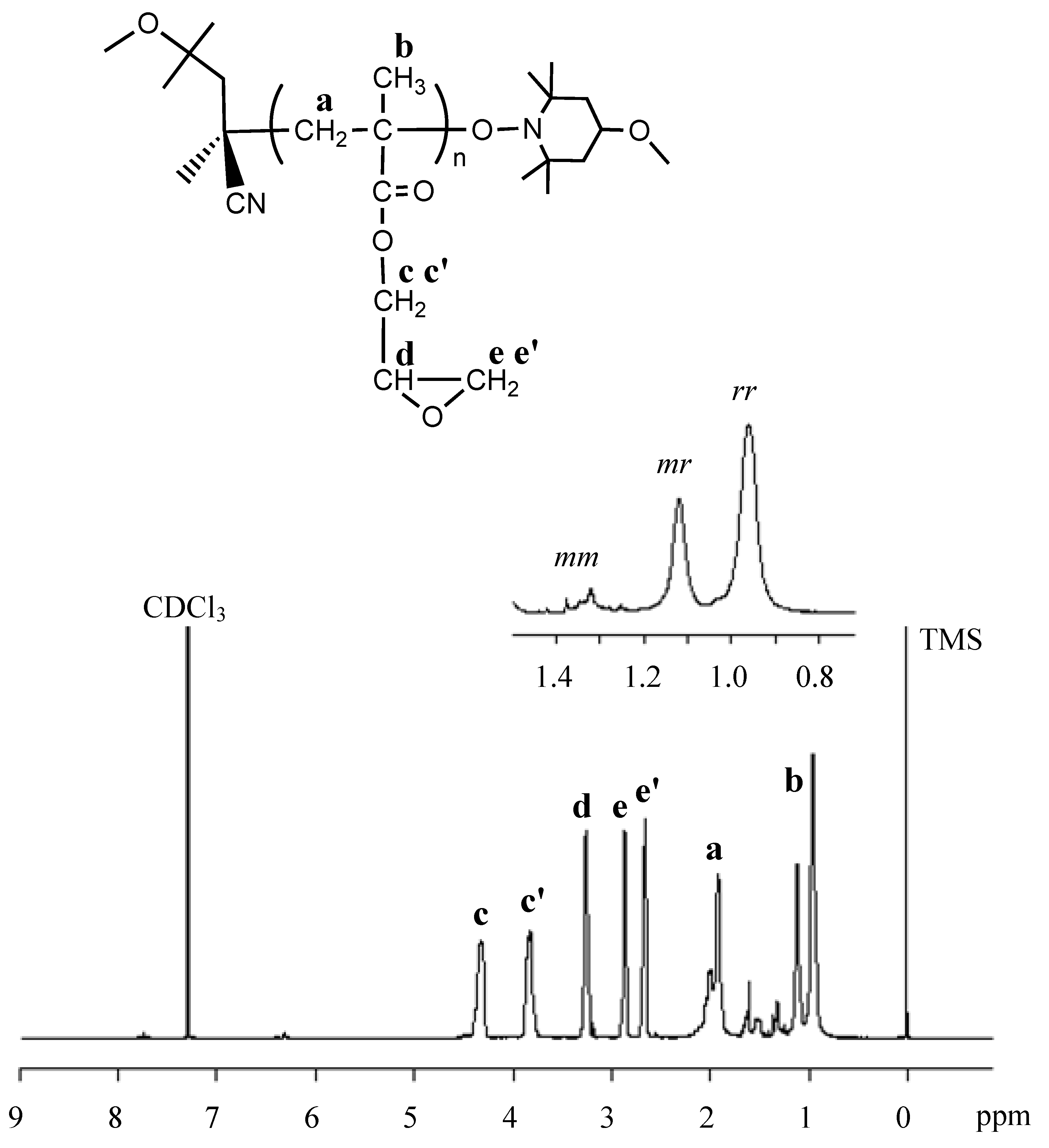

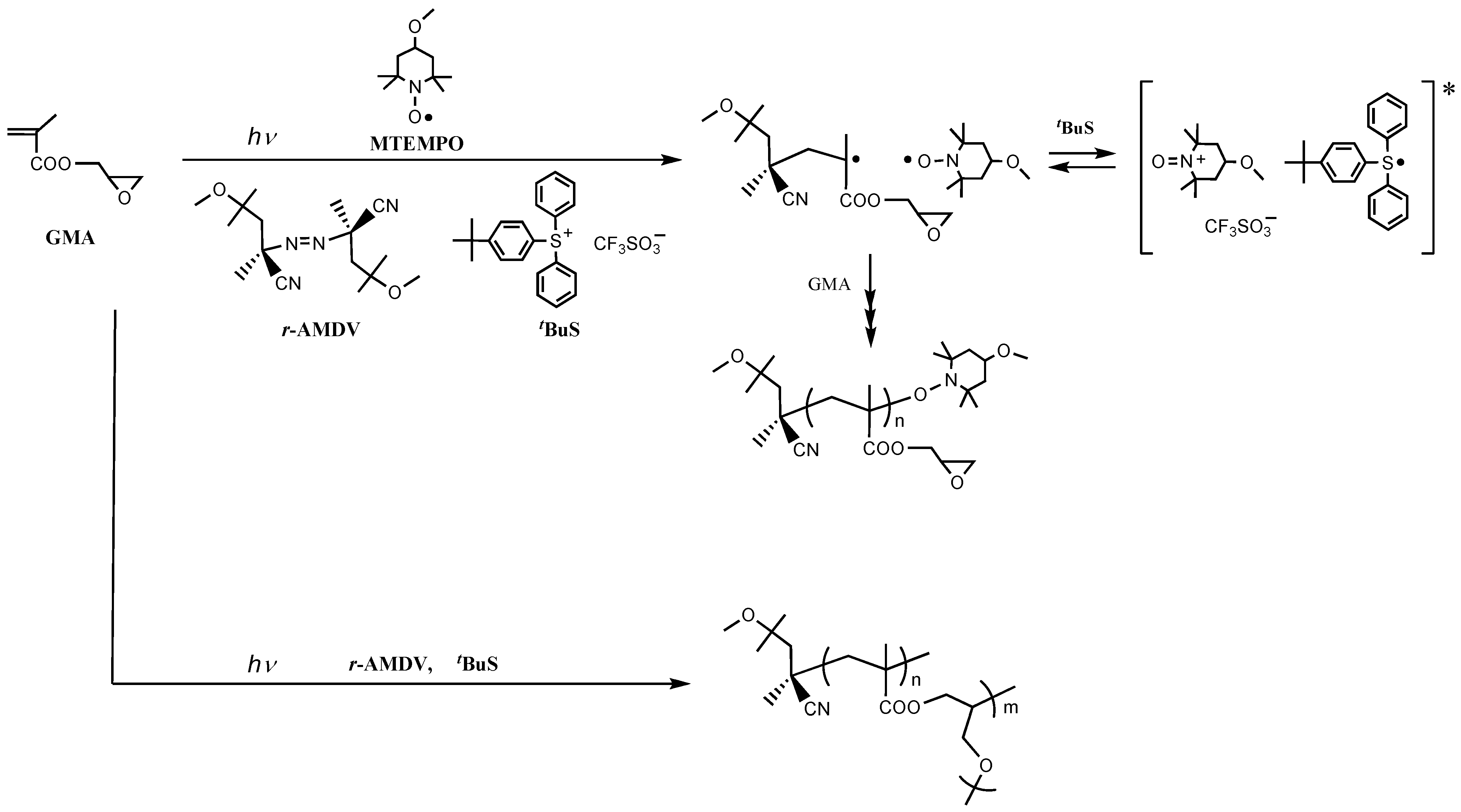

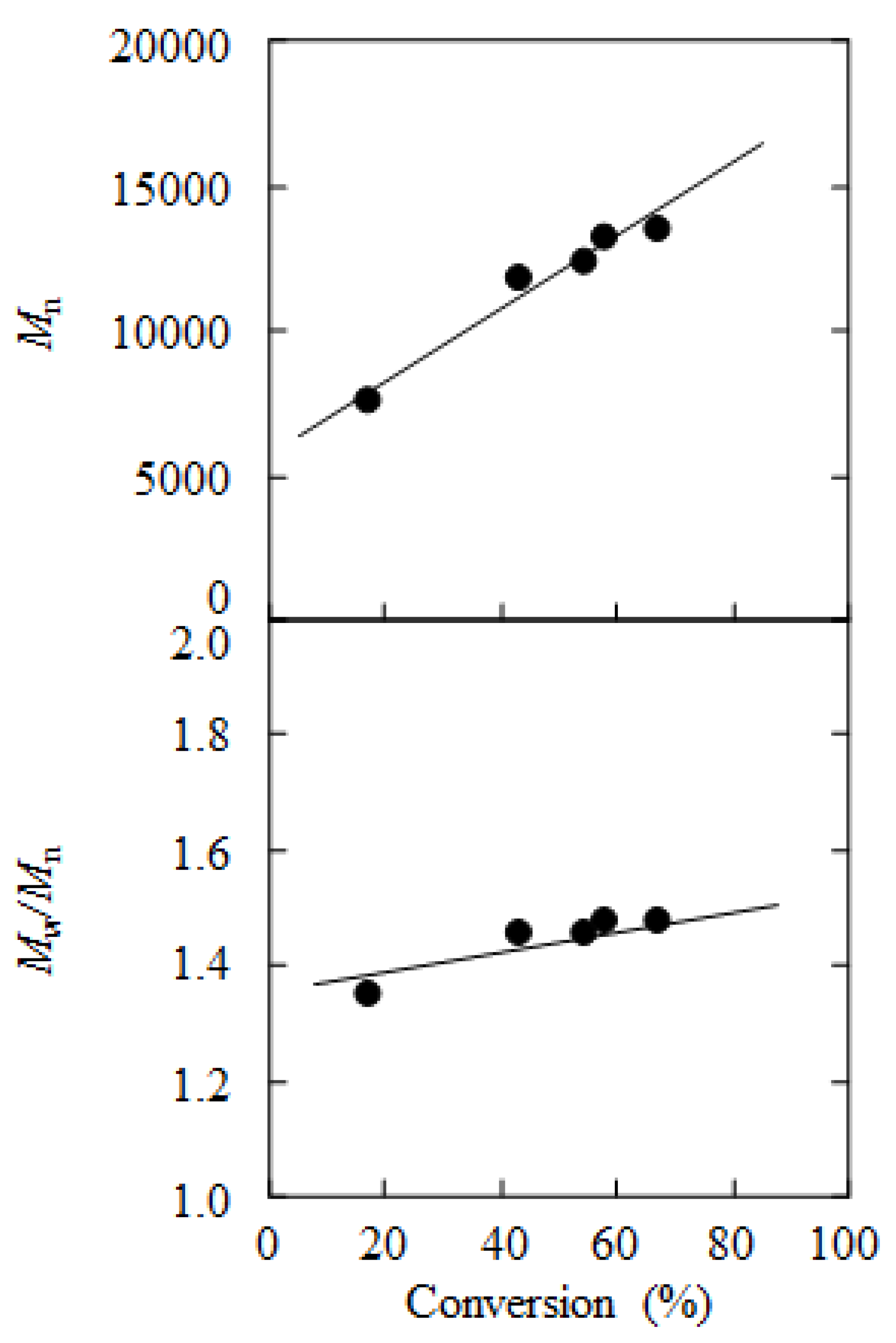

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Meier, K.; Zweifel, H. Imaging with iron arene photoinitiators. J. Imag. Sci. 1986, 30, 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Cai, Q.; Li, Y.; Kang, E.; Neoh, K.G. Covalent immobilization of glucose oxidase on well-defined poly(glycidyl methacrylate)−Si(111) hybrids from surface-initiated atom-transfer radical polymerization. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H.; Endo, T. Incorporation of carbon dioxide into poly(glycidyl methacrylate). Macromolecules 1992, 25, 4824–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, J.V. Cationic photopolymerization of alkyl glycidyl ethers. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 3036–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, J.V. Design and synthesis of multifunctional glycidyl ethers that undergo frontal polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 6435–6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, J.V. The discovery and development of onium salt cationic photoinitiators. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 1999, 37, 4241–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaite, R.; Stanislovaityte, E.; Grazulevicius, J.V. Cationic photopolymerization of 1,3-di(9-carbazolyl)-2-propanol glycidyl ether. Monatsh. Chem. 2008, 139, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu-Vasii, L.L.; Dimonie, M.D.; Abadie, M.J.M. Kinetic model of photoinitiated polymerization of phenyl glycidyl ether monomer. Polym. Int. 2008, 47, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, K.; Zweifel, H. Photoinitiated cationic polymerization of epoxides with iron-arene complexes. J. Rad. Curing 1986, 13, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, E. Photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate by a nitroxide mediator. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2008, 286, 1663–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate by 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl in the presence of a photo-acid generator. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2009, 287, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate using alkoxyamine as an initiator. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization of vinyl acetate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate using (4-tert-butylphenyl)diphenylsulfonium triflate as a photo-acid generator. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Effect of azoinitiators on nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Effects of initiators and photo-acid generators on nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Stability of growing polymer chain ends for nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate in solution. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate in the presence of (η6-benzene)(η5-cyclopentadienyl)FeII hexafluorophosphate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2010, 288, 1745–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Nitroxide-mediated photo-controlled/living radical polymerization of ethyl acrylate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2011, 289, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Nitroxide-mediated photo-controlled/living radical dispersion polymerization of methyl methacrylate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2011, 289, 1625–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Photo-controlled/living radical polymerization of tert-butyl methacrylate in the presence of a photo-acid generator using a nitroxide mediator. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2012, 290, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Aqueous photo-living radical polymerization of sodium methacrylate using a water-soluble nitroxide mediator. Int. Sch. Res. Netw. ISRN Polym. Sci. 2012. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, E. Effects of illuminance and heat rays on photo-controlled/living radical polymerization mediated by 4-methoxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl. Int. Sch. Res. Netw. ISRN Polym. Sci. 2012. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, E. Synthesis of poly(methyl methacrylate)-block-poly(tetrahydrofuran) by photo-living radical polymerization using a 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl macromediator. Colloid Polym Sci. 2009, 287, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E. Graft copolymerization of methyl methacrylate on polystyrene backbone through nitroxide-mediated photo-living radical polymerization. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2011, 289, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.R.; Neumann, M.G. Cationic photopolymerization of tetrahydrofuran: A mechanistic study on the use of a sulfonium salt-phenothiazine initiation system. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 2001, 39, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.R.; Neumann, M.G. Mechanistic study of tetrahydrofuran polymerization photoinitiated by a sulfonium salt/thioxanthone system. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2001, 202, 2776–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Kajiwara, A.; Morishima, Y.; Kamachi, M. Radical/cation transformation polymerization and its application to the preparation of block copolymers of p-methoxystyrene and cyclohexene oxide. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2354–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Miyazawa, T.; Shiihashi, S.; Okawara, M. Oxidation of hydroxide ion by immonium oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 6732–6734. [Google Scholar]

- Semmelhack, M.F.; Schmid, C.R. Nitroxy-mediated electrooxidation of amines to nitriles and carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 3877–3878. [Google Scholar]

- Semmelhack, M.F.; Chou, C.S.; Cortes, D.A. Nitroxy-mediated electrooxidation of aalcohols to aldehydes and ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 4492–4494. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, S.P.; Gatechair, L.R.; Jilek, J.H. Photoinitiation of cationic polymerization. III. Photosensitization of diphenyliodonium and triphenylsulfonium salts. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 1984, 22, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, P.S.; Rosenthal, S. The electrochemical reduction of the triphenylsulfonium ion. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1968, 16, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, J.V.; Sangermano, M. Visible and long-wavelength photoinitiated cationic polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 2001, 39, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zheng, H.; Lu, L.; Liu, P.; Cai, Y. Highly efficient and well-controlled ambient temperature RAFT polymerization of glycidyl methacrylate under visible light radiation. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 5091–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Moriya, O.; Endo, T. Efficient fixation of carbon dioxide into poly(glycidyl methacrylate) containing pendant crown ether. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, Y.; Gotanda, K.; Murata, K.; Suemura, M.; Sano, A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Oka, M.; Matsugi, M. Practical radical additions under mild conditions using 2,2'-azobis(2,4-dimethyl-4-methoxyvaleronitrile)[V-70] as an initiator. Org. Process Res. Dev. 1998, 2, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, T.; Endo, T.; Shiihashi, S.; Ogawara, M. Selective oxidation of alcohols by oxoaminium salts (R2N = O+X−). J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshida, E. Selective Controlled/Living Photoradical Polymerization of Glycidyl Methacrylate, Using a Nitroxide Mediator in the Presence of a Photosensitive Triarylsulfonium Salt. Polymers 2012, 4, 1580-1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym4031580

Yoshida E. Selective Controlled/Living Photoradical Polymerization of Glycidyl Methacrylate, Using a Nitroxide Mediator in the Presence of a Photosensitive Triarylsulfonium Salt. Polymers. 2012; 4(3):1580-1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym4031580

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshida, Eri. 2012. "Selective Controlled/Living Photoradical Polymerization of Glycidyl Methacrylate, Using a Nitroxide Mediator in the Presence of a Photosensitive Triarylsulfonium Salt" Polymers 4, no. 3: 1580-1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym4031580

APA StyleYoshida, E. (2012). Selective Controlled/Living Photoradical Polymerization of Glycidyl Methacrylate, Using a Nitroxide Mediator in the Presence of a Photosensitive Triarylsulfonium Salt. Polymers, 4(3), 1580-1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym4031580