Adenosine-Related Mechanisms in Non-Adenosine Receptor Drugs

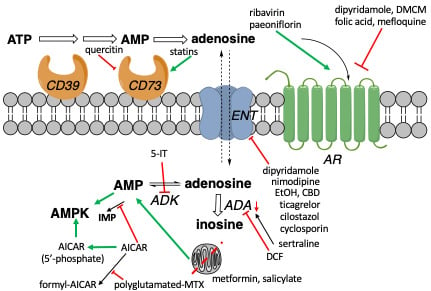

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Endogenous Adenosine

1.2. Action of Various Drugs Involves Adenosine

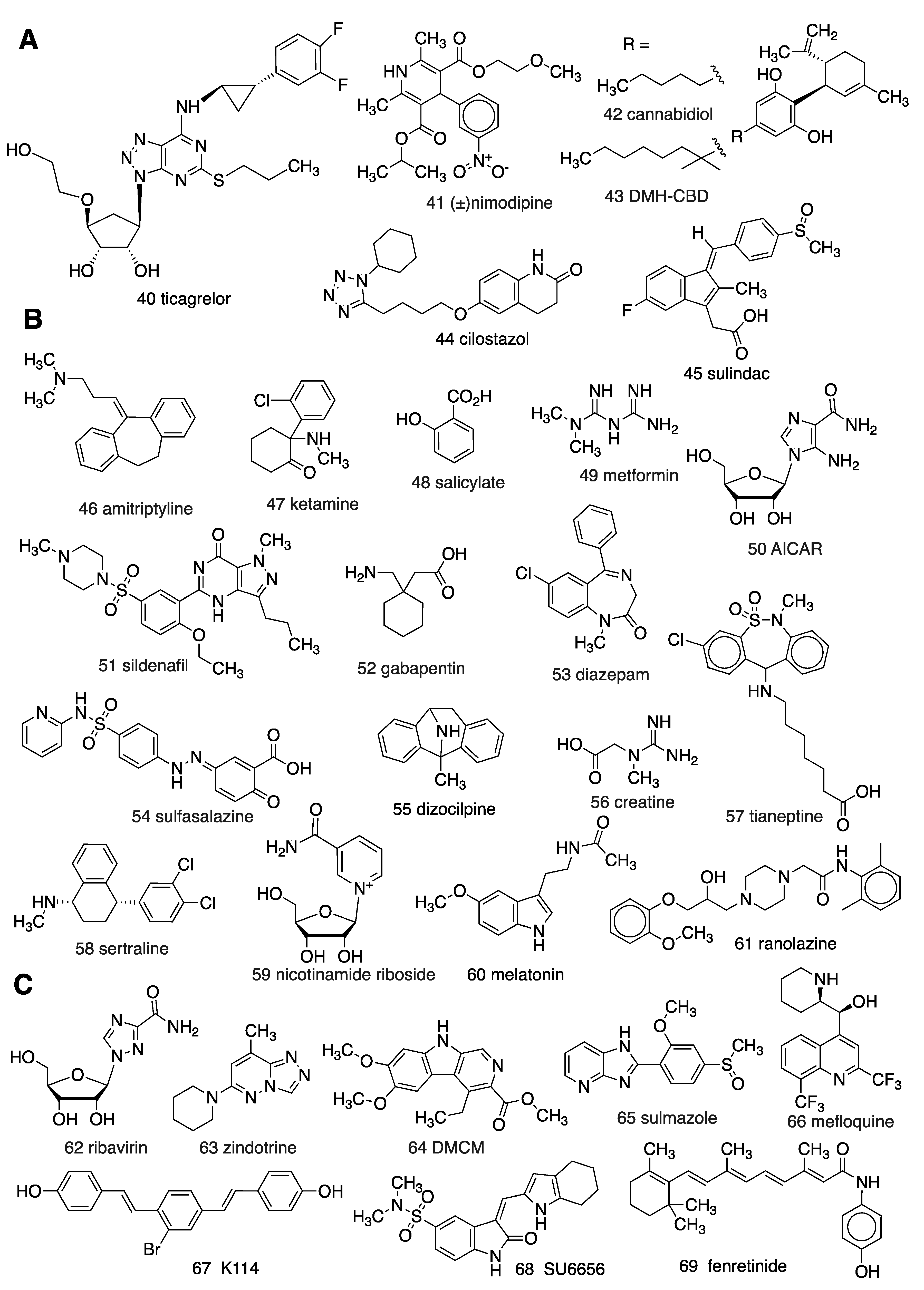

1.3. Known AR Ligands

1.4. Known Modulators of Adenosine Pharmacokinetics

2. Proposed Adenosinergic Mechanism of Diverse Drugs and Treatments

2.1. Vasoactive and Other Cardiovascular Effects

2.2. Treatment of Inflammation

2.3. Pain, Antidepressant, Sleep, and Other Behavioral Intervention

2.4. Anticancer Drugs

2.5. AR Interaction with Other GPCRs

2.6. Other Unanticipated Interactions with ARs

3. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonioli, L.; Fornai, M.; Blandizzi, C.; Haskó, G. The Adenosine Receptors. In Adenosine Regulation of the Immune System; Varani, P.A.K., Gessi, S., Merighi, S., Vincenzi, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Liu, N.; Jacobson, K.A.; Gavrilova, O.; Reitman, M.L. Physiology and effects of nucleosides in mice lacking all four adenosine receptors. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskó, G.; Linden, J.; Cronstein, B.; Pacher, P. Adenosine receptors: Therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2008, 7, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, L.; Fornai, M.; Colucci, R.; Ghisu, N.; Da Settimo, F.; Natale, G.; Kastsiuchenka, O.; Duranti, E.; Virdis, A.; Vassalle, C.; et al. Inhibition of adenosine deaminase attenuates inflammation in experimental colitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2007, 322, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boison, D. Adenosine kinase: Exploitation for therapeutic gain. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 906–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, H.E.; Hoffer, M.E.; McAllister, D.R.; Laikind, P.K.; Lane, T.A.; Schmid-Schoenbein, G.W.; Engler, R.L. Increased adenosine concentration in blood from ischemic myocardium by AICA riboside. Effects on flow, granulocytes, and injury. Circulation 1989, 80, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, J.R.; Baldwin, S.A.; Young, J.D.; Cass, C.E. Nucleoside transport and its significance for anticancer drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updates 1998, 1, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillis, J.W.; Wu, P.H. The effect of various centrally active drugs on adenosine uptake by the central nervous system. Com. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Comp. Pharmacol. 1982, 72, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Cronstein, B.N. Understanding the mechanisms of action of methotrexate implications for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2007, 65, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, T.W.; Perkins, M.N. Is adenosine the mediator of opiate action on neuronal firing? Nature 1979, 281, 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Risley, E.A.; Huff, J.R. Interaction of putative anxiolytic agents with central adenosine receptors. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1981, 59, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.W.; Yang, C.; Sit, A.S.; Lin, S.Y.; Ho, E.Y.; Leung, G.P. Physiological and pharmacological roles of vascular nucleoside transporters. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2012, 59, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell-Casteel, R.C.; Hays, F.A. Equilibrative nucleoside transporters—A review. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2017, 36, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newby, A.C. Adenosine and the concept of ‘retaliatory metabolites. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1984, 9, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camici, M.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Tozzi, M.G. The inside story of adenosine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, B.; Beavis, P.A.; Darcy, P.K.; Stagg, J. Immunosuppressive activities of adenosine in cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 29, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediero, A.; Cronstein, B.N. Adenosine and bone metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, H.J. The Adenosine A2B receptor drives osteoclast-mediated bone resorption in hypoxic microenvironments. Cells 2019, 8, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnstock, G. Purinergic signalling: Therapeutic developments. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.H.; Schrader, J.; Deussen, A. Turnover of adenosine in plasma of human and dog blood. Am. J. Physiol. 1989, 256, C799–C806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blardi, P.; Laghi Pasini, F.; Urso, R.; Frigerio, C.; Volpi, L.; De Giorgi, L.; Di Perri, T. Pharmacokinetics of exogenous adenosine in man after infusion. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 44, 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.E.; Jacobson, K.A. Recent developments in adenosine receptor ligands and their potential as novel drugs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2011, 1808, 1290–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.C.; Kreckler, L.M.; Van Orman, J.; Auchampach, J.A. Pharmacological characterization of recombinant mouse adenosine receptors expressed in HEK 293 cells. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium of Nucleosides and Nucleotides, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 9–11 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carlin, J.L.; Jain, S.; Gizewski, E.; Wan, T.C.; Tosh, D.K.; Xiao, C.; Auchampach, J.A.; Jacobson, K.A.; Gavrilova, O.; Reitman, M.L. Hypothermia in mouse is caused by adenosine A1 and A3 receptor agonists and AMP via three distinct mechanisms. Neuropharmacology 2017, 114, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tosh, D.K.; Rao, H.; Bitant, A.; Salmaso, V.; Mannes, P.; Lieberman, D.I.; Vaughan, K.L.; Mattison, J.A.; Rothwell, A.C.; Auchampach, J.A.; et al. Design and in vivo characterization of A1 adenosine receptor agonists in the native ribose and conformationally-constrained (N)-methanocarba series. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1502–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnouri, M.W.; Jepards, S.; Casari, A.; Schiedel, A.C.; Hinz, S.; Müller, C.E. Selectivity is species-dependent: Characterization of standard agonists and antagonists at human, rat, and mouse adenosine receptors. Purinergic. Signal. 2015, 11, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, S.P.K.; Khole, S.; Jagadish, N.; Ghosh, D.; Gadgil, V.; Sinkar, V.; Ghaskadbi, S.S. Andrographolide protects liver cells from H2O2 induced cell death by upregulation of Nrf-2/HO-1 mediated via adenosine A2a receptor signalling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowaluk, E.A.; Mikusa, J.; Wismer, C.T.; Zhu, C.Z.; Schweitzer, E.; Lynch, J.J.; Jarvis, M. ABT-702 (4-Amino-5-(3-bromophenyl)-7-(6-morpholino-pyridin-3-yl)pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidine), a Novel orally effective adenosine kinase inhibitor with analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. II. In vivo characterization in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2000, 295, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Terasaka, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Kuno, M.; Nakanishi, I. A highly potent non-nucleoside adenosine deaminase inhibitor: Efficient drug discovery by intentional lead hybridization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Liao, J.K. Translational therapeutics of dipyridamole. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, S39–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, C.L.; Adams, C.A.; Knight, E.J.; Nam, H.W.; Choi, D.S. An essential role for adenosine signaling in alcohol abuse. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2010, 3, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Drury, A.N.; Szent-Györgyi, A. The physiological activity of adenine compounds with especial reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. J. Physiol. 1929, 68, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.J.; Webb, R.L.; Oei, H.H.; Ghai, G.R.; Zimmerman, M.B.; Williams, M. CSG21680, an A2 selective adenosine receptor agonist with preferential hypotensive activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989, 251, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, L.; Kulshrestha, R.; Singh, N.; Jaggi, A.S. Mechanisms involved in adenosine pharmacological preconditioning-induced cardioprotection. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 22, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, T.C.; Tampo, A.; Kwok, W.M.; Auchampach, J.A. Ability of CP-532,903 to protect mouse hearts from ischemia/reperfusion injury is dependent on expression of A3 adenosine receptors in cardiomyoyctes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 163, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, G.F. Role of adenosine in delayed preconditioning of myocardium. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 55, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendra, H.; Diaz, R.J.; Harvey, K.; Tropak, M.; Callahan, J.; Hinek, A.; Wilson, G.J. Interaction of δ and κ opioid receptors with adenosine A1 receptors mediates cardioprotection by remote ischemic preconditioning. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2013, 60, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, F.N.; Das, A.; Thomas, C.S.; Yin, C.; Kukreja, R.C. Adenosine A1 receptor mediates delayed cardioprotective effect of sildenafil in mouse. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2007, 43, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.E.; Davis, C.M.; Wei, K.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, Z.; Nugent, M.; Scott, K.L.L.; Liu, L.; Nagarajan, S.; Alkayed, N.J.; et al. Ranolazine may exert its beneficial effects by increasing myocardial adenosine levels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H189–H202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.Y.; Lee, M.-S. New mechanisms of metformin action: Focusing on mitochondria and the gut. J. Diabetes Investig. 2015, 6, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D.G.; Pearson, E.R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaspa, M.A.; Cicerchi, C.; Garcia, G.; Li, N.; Roncal-Jimenez, C.A.; Rivard, C.J.; Hunter, B.; Andres-Hernando, A.; Ishimoto, T.; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G.; et al. Counteracting roles of AMP deaminase and AMP kinase in the development of fatty liver. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Parakhia, R.A.; Ochs, R.S. Metformin activates AMP kinase through inhibition of AMP deaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, M.; Riksen, N.P.; Davidson, S.M.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Monteiro, P.; Goncalves, L.; Providencia, L.; Rongen, G.A.; Smits, P.; Mocanu, M.M.; et al. Metformin prevents myocardial reperfusion injury by activating the adenosine receptor. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2009, 53, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, C.R.; Denman, B.A.; Mazzo, M.R.; Armstrong, M.L.; Reisdorph, N.; McQueen, M.B.; Seals, D.R. Chronic nicotinamide riboside supplementation is well-tolerated and elevates NAD+ in healthy middle-aged and older adults. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylander, S.; Femia, E.A.; Scavone, M.; Berntsson, P.; Asztély, A.-K.; Nelander, K.; Cattaneo, M. Ticagrelor inhibits human platelet aggregation via adenosine in addition to P2Y12 antagonism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, M.; Faioni, E.M. Why does ticagrelor induce dyspnea? Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 108, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Striessnig, J.; Zernig, G.; Glossmann, H. Glossmann Human red-blood-cell Ca2+-antagonist binding sites. Evidence for an unusual receptor coupled to the nucleoside transporter. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985, 150, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Tissier, R.; Ghaleh, B.; Drogies, T.; Felix, S.B.; Krieg, T. Cardioprotective effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists at reperfusion. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, T.N.; Deinum, J.; Bilos, A.; Donders, A.R.; Rongen, G.A.; Riksen, N.P. The effect of eplerenone on adenosine formation in humans in vivo: A double-blinded randomised controlled study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shakur, Y.; Yoshitake, M.; Kambayashi, J. Cilostazol (Pletal®): A dual inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase type 3 and adenosine uptake. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 2006, 19, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, M.; Yoshitake, M.; Kambayashi, J.; Liu, Y. Cilostazol increases tissue blood flow in contracting rabbit gastrocnemius muscle. Circ. J. 2010, 74, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Murakami, H.M.; Iwasa, M.; Sumi, S.; Yamada, Y.; Minatoguchi, S. Cilostazol protects the heart against ischaemia reperfusion injury in a rabbit model of myocardial infarction: Focus on adenosine, nitric oxide and mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011, 38, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guieu, R.; Dussol, B.; Devaux, C.; Sampol, J.; Brunet, P.; Rochat, H.; Bechis, G.; Berland, Y.F. Interactions between cyclosporine A and adenosine in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 1998, 53, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.R.; Storer, R.I. A semi-quantitative translational pharmacology analysis to understand the relationship between in vitro ENT1 inhibition and the clinical incidence of dyspnoea and bronchospasm. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 317, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, P.; Oyen, W.J.G.; Dekker, D.; Van den Broek, P.H.H.; Wouters, C.W.; Boerman, O.C.; Scheffer, G.J.; Smits, P.; Rongen, G.A. Rosuvastatin increases extracellular adenosine formation in humans in vivo. A new perspective on cardiovascular protection. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Montesinos, M.C.; Weissmann, G. Salicylates and sulfasalazine, but not glucocorticoids, inhibit leukocyte accumulation by an adenosine-dependent mechanism that is independent of inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis and p105 of NFkappaB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 6377–6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, J.A.M.; Kooloos, W.M.; De Jonge, R.; De Vries-Bouwstra, J.K.; Allaart, C.F.; Linssen, A.; Collee, G.; De Sonnaville, P.; Lindemans, J.; Huizinga, T.W.J.; et al. Relationship between genetic variants in the adenosine pathway and outcome of methotrexate treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 2830–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, J.F.; Ramey, D.R.; Singh, G.; Morfeld, D.; Bloch, D.A.; Raynauld, J. A reevaluation of aspirin therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1993, 153, 2465–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebich, B.L.; Biber, K.; Lieb, K.; Van Calker, D.; Berger, M.; Bauer, J.; Gebicke-Haerter, P. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in rat microglia is induced by adenosine A2a-receptors. Glia 2018, 18, 152–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfine, A.B.; Fonseca, V.; Jablonski, K.A.; Chen, Y.-D.I.; Tipton, L.; Staten, M.A.; Shoelson, S.E. Salicylate (Salsalate) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadangi, P.; Longaker, M.; Naime, D.; Levin, R.I.; Recht, P.A.; Montesinos, M.C.; Buckley, M.T.; Carlin, G.; Cronstein, B.N. The anti-inflammatory mechanism of sulfasalazine is related to adenosine release at inflamed sites. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 1937–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Barczyk, K.; Ehrchen, J.; Tenbrock, K.; Ahlmann, M.; Kneidl, J.; Viemann, D.; Roth, J. Glucocorticoids promote survival of anti-inflammatory macrophages via stimulation of adenosine receptor A3. Blood 2010, 116, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazar, J.; Rogachev, B.; Shaked, G.; Ziv, N.Y.; Czeiger, D.; Chaimovitz, C.; Zlotnik, M.; Mukmenev, I.; Byk, G.; Douvdevani, A. Involvement of adenosine in the antiinflammatory action of ketamine. Anesthesiology 2005, 102, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Hong, S.Y.; Wang, J.; Rehan, S.; Liu, W.; Peng, H.; Das, M.; Li, W.; Bhat, S.; Peiffer, B.; et al. Rapamycin-inspired macrocycles with new target specificity. Nat. Chem. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, E.J.; Auchampach, J.A.; Hillard, C.J. Inhibition of an equilibrative nucleo- side transporter by cannabidiol: A mechanism of cannabinoid immunosuppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7895–7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, S. Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: A review of their effects on inflammation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, A.; Tolón, M.R.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.; Romero, J.; Martinez-Orgado, J. The neuroprotective effect of cannabidiol in an in vitro model of newborn hypoxic–ischemic brain damage in mice is mediated by CB2 and adenosine receptors. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Pinheiro, M.L.; Vitoretti, L.B.; Mariano-Souza, D.P.; Quinteiro-Filho, W.M.; Akamine, A.T.; Almeida, V.I.; Quevedo, J.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; et al. Cannabidiol, a non-psychotropic plant-derived cannabinoid, decreases inflammation in a murine model of acute lung injury: Role for the adenosine A2A receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 678, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, G.I.; Auchampach, J.A.; Hillard, C.J.; Zhu, G.; Yousufzai, B.; Mian, S.; Khalifa, Y. Mediation of cannabidiol anti-inflammation in the retina by equilibrative nucleoside transporter and A2A adenosine receptor. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 5526–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.L.; Silveira, G.T.; Wanderlei, C.W.; Cecilio, N.T.; Maganin, A.G.M.; Franchin, M.; Cunha, T.M. DMH-CBD, a cannabidiol analog with reduced cytotoxicity, inhibits TNF production by targeting NF-kB activity dependent on A2A receptor. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 368, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Adebiyi, M.G.; Luo, J.; Sun, K.; Le, T.-T.T.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y. Sustained elevated adenosine via ADORA2B promotes chronic pain through neuro-immune interaction. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, K.A.; Giancotti, L.A.; Lauro, F.; Mufti, F.; Salvemini, D. Treatment of chronic neuropathic pain: Purine receptor modulation. Pain 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.I.; White, T.D.; Jhamandas, K.H.; Sawynok, J. Morphine releases endogenous adenosine from the spinal cord in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1987, 141, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandner-Kiesling, A.; Li, X.; Eisenach, J.C. Morphine-induced spinal release of adenosine is reduced in neuropathic rats. Anesthesiology 2001, 95, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, D.J.; Schmitt, L.I.; Hines, R.M.; Moss, S.J.; Haydon, P.G. Antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation require astrocyte-dependent adenosine mediated signaling. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serchov, T.; Clement, H.W.; Schwartz, M.K.; Iasevoli, F.; Tosh, D.K.; Idzko, M.; Jacobson, K.A.; De Bartolomeis, A.; Normann, C.; Biber, K.; et al. Increased signaling via adenosine A1 receptors, sleep deprivation, imipramine, and ketamine inhibit depressive-like behavior via induction of Homer1a. Neuron 2015, 87, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.P.; Pazini, F.L.; Rosa, J.M.; Ramos-Hryb, A.B.; Oliveira, Á.; Kaster, M.P.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Creatine, similarly to ketamine, affords antidepressant-like effects in the tail suspension test via adenosine A1 and A2A receptor activation. Purinergic Signal. 2015, 11, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.M.; Fisher, A.; Cooke, M.J.; Thompson, I.D.; Stone, T.W. The involvement of adenosine receptors in the effect of dizocilpine on mice in the elevated plus-maze. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997, 7, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Reid, A.R.; Sawynok, J. Spinal serotonin 5-HT7 and adenosine A1 receptors, as well as peripheral adenosine A1 receptors, are involved in antinociception by systemically administered amitriptyline. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 698, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kwon, S.Y.; Jung, H.S.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y.S.; In, J.H.; Choi, J.W.; A Kim, J.; Joo, J.D. Amitriptyline inhibits the MAPK/ERK and CREB pathways and proinflammatory cytokines through A3AR activation in rat neuropathic pain models. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, S.; Hocaoglu, N.; Buyukdeligoz, M.; Gurdal, H. Binding of amitriptyline to adenosine A1 or A2A receptors. Using radioligand binding assay. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 14, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, D.F.; Prado, M.R.B.; Brito, R.N.; Darugo-Neto, E.; Batisti, A.P.; Emer, A.E.; Mazzardo-Martins, L.; Santos, A.R.S.; Piovezan, A.P. Caffeine prevents antihyperalgesic effect of gabapentin in an animal model of CRPS-I: Evidence for the involvement of spinal adenosine A1 receptor. J. Periph. Nerv. Syst. 2015, 20, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; Quiroz, C.; Guitart, X.; Rea, W.; Seyedian, A.; Moreno, E.; Casadó-Anguera, V.; Díaz-Ríos, M.; Casadó, V.; Clemens, S.; et al. Pivotal role of adenosine neurotransmission in restless legs syndrome. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, D.F.; Brito, R.N.; Stramosk, J.; Batisti, A.P.; Madeira, F.; Turnes, B.L.; Piovezan, A.P. Peripheral neurobiologic mechanisms of antiallodynic effect of warm water immersion therapy on persistent inflammatory pain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 93, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boß, M.; Newbatt, Y.; Gupta, S.; Collins, I.; Brüne, B.; Namgaladze, D. AMPK-independent inhibition of human macrophage ER stress response by AICAR. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, A.E.; Pearson, T.; Currie, A.J.; Dale, N.; Hawley, S.A.; Sheehan, M.; Hirst, W.; Michel, A.D.; Randall, A.; Hardie, D.G.; et al. AICA riboside both activates AMP-activated protein kinase and competes with adenosine for the nucleoside transporter in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 2004, 88, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T.; Nozu, T.; Kumei, S.; Takakusaki, K.; Miyagishi, S.; Ohhira, M. Adenosine A1 receptors mediate the intracisternal injection of orexin-induced antinociceptive action against colonic distension in conscious rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 362, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futatsuki, T.; Yamashita, A.; Ikbar, K.N.; Yamanaka, A.; Arita, K.; Kakihana, Y.; Kuwaki, T. Involvement of orexin neurons in fasting- and central adenosine-induced hypothermia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameyaw, E.O.; Kukuia, K.K.E.; Thomford, A.K.; Kyei, S.; Mante, P.K.; Boampong, J.N. Analgesic properties of aqueous leaf extract of Haematostaphis barteri: Involvement of ATP-sensitive potassium channels, adrenergic, opioidergic, muscarinic, adenosinergic and serotoninergic pathways. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 27, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z.A.; Rahim, M.H.A.; Roosli, R.A.J.; Sani, M.M.; Omar, M.H.; Tohid, S.F.M.; Othman, F.; Ching, S.M.; Arifah, A.K. Antinociceptive Activity of Methanolic Extract of Clinacanthus nutans Leaves: Possible Mechanisms of Action Involved. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.G.; Tosh, D.K.; Jain, S.; Yu, J.; Suresh, R.R.; Jacobson, K.A. Chapter 4. A1 adenosine receptor agonists, antagonists and allosteric modulators. In The Receptors, the Adenosine Receptors; Varani, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 34, pp. 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, E.D.; Da Costa, P.F.; Medeiros, L.F.; Souza, A.; Battastini, A.M.O.; Von Poser, G.L.; Bonan, C.; Torres, I.L.S.; Rates, S.M.K. Uliginosin B, a possible new analgesic drug, acts by modulating the adenosinergic system. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-L.; Yu, G.; Yi, S.-P.; Zhang, F.-Y.; Wang, Z.-T.; Huang, B.; Su, R.-B.; Jia, Y.-X.; Gong, Z.-H. Antinociceptive effects of incarvillateine, a monoterpene alkaloid from Incarvillea sinensis, and possible involvement of the adenosine system. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N.; Chen, M.; Fujita, T.; Xu, Q.; Peng, W.; Liu, W.; Jensen, T.K.; Pei, Y.; Wang, F.; Han, X.; et al. Adenosine A1 receptors mediate local anti-nociceptive effects of acupuncture. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 883–888. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.-Y.; Hsieh, L.-C.; Huang, C.-P.; Lin, Y.-W. Electroacupuncture Attenuates CFA-induced inflammatory pain by suppressing Nav1.8 through S100B, TRPV1, opioid, and adenosine pathways in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, K.; Xifró, R.A.; Hartweg, J.L.; Spitzlei, P.; Meis, K.; Molderings, G.J.; von Kügelgen, I. Inhibitory effects of benzodiazepines on the adenosine A2B receptor mediated secretion of interleukin-8 in human mast cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 700, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, M.; Pravica, M.; Radulovacki, M. Chronic administration of diazepam downregulates adenosine receptors in the rat brain. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988, 30, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.B.; Cotreau, M.M.; Greenblatt, D.J. Effects of benzodiazepine administration on A1 adenosine receptor binding in-vivo and ex-vivo. J. Pharmacy Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 700–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimzadeh, K.; Jafarpour, H.; Adldoost, S. Sertraline alters level of adenosine deaminase activity, oxidative stress markers and cardiac biomarkers (homocysteine cardiac troponin I) in rats. Pharm. Biomed. Res. 2017, 3, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Uzbay, T.I.; Kayir, H.; Ceyhan, M. Effects of tianeptine on onset time of pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in mice: Possible role of adenosine A1 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 32, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, K.R.; Binfaré, R.W.; Budni, J.; Rosa, A.O.; Santos, A.R.S.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Involvement of the adenosine A1 and A2A receptors in the antidepressant-like effect of zinc in the forced swimming test. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psych. 2010, 32, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadzki, P.P.; Bajpai, R.; Kyaw, B.M.; Roberts, N.J.; Brzezinski, A.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Car, J. Melatonin and health: An umbrella review of health outcomes and biological mechanisms of action. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, A.V.; Mosser, E.A.; Oikonomou, G.; Prober, D.A. Melatonin is required for the circadian regulation of sleep. Neuron 2015, 85, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, L.E.; Diamond, I.; Casso, D.J.; Franklin, C.; Gordon, A.S. Ethanol increases extracellular adenosine by inhibiting adenosine uptake via the nucleoside transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 1946–1951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Dong, H.; Xu, X.-H.; Yuan, X.-S.; Chen, Z.-K.; Chen, J.-F.; Qu, W.M.; Huang, Z.-L. Adenosine A2A receptor mediates hypnotic effects of ethanol in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, V.; Richardson, M.J.E.; Wall, M.J. Acute ethanol exposure has bidirectional actions on the endogenous neuromodulator adenosine in rat hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1471–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Naassila, M.; Ledent, C.; Daoust, M. Low ethanol sensitivity and increased ethanol consumption in mice lacking adenosine A2A receptors. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 10487–10493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.-S.; Cascini, M.-G.; Mailliard, W.; Young, H.; Paredes, P.; McMahon, T.; Messing, R.O. The type 1 equilibrative nucleoside transporter regulates ethanol intoxication and preference. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny-Beke, A.; Jakab, A.; Zsuga, J.; Vecsernyes, M.; Karsai, D.; Pasztor, F.; Gesztelyi, R. Adenosine deaminase inhibition enhances the inotropic response mediated by A1 adenosine receptor in hyperthyroid guinea pig atrium. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 56, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginés, S.; Hillion, J.; Torvinen, M.; Le Crom, S.; Casadó, V.; Canela, E.I.; Rondin, S.; Lew, J.Y.; Watson, S.; Zoli, M.; et al. Dopamine D1 and adenosine A1 receptors form functionally interacting heteromeric complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8606–8611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Wydra, K.; Li, X.; Rodriguez, D.; Carlsson, J.; Jastrzębska, J.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. Disruption of A2AR-D2R heteroreceptor complexes after A2AR transmembrane 5 peptide administration enhances cocaine self-administration in rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 7038–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, E.A.; Baltos, J.A.; Nguyen, A.T.N.; Christopoulos, A.; White, P.J.; May, L.T. New paradigms in adenosine receptor pharmacology: Allostery, oligomerization and biased agonism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 4036–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Fuxe, K. Adenosine heteroreceptor complexes in the basal ganglia are implicated in Parkinson’s disease and its treatment. J. Neural. Transm. 2019, 126, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.G. Development of growth hormone secretagogues. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, M.C.; Camiña, J.P.; Díaz-Rodríguez, E.; Alvear-Perez, R.; Llorens-Cortes, C.; Casanueva, F.F. Adenosine does not bind to the growth hormone secretagogue receptor type-1a (GHS-R1a). J. Endocrinol. 2006, 191, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, R.J.; Adams, D.R.; Bebbington, D.; Benwell, K.; Cliffe, I.A.; Dawson, C.E.; Dourish, C.T.; Fletcher, A.; Gaur, S.; Giles, P.R.; et al. Antagonists of the human adenosine A2A receptor. Part 1: Discovery and synthesis of thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidine-4-methanone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2916–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, S.M.; Ji, X.D.; Melman, N.; Olah, M.E.; Jain, R.; Evans, P.; Glashofer, M.; Padgett, W.L.; Cohen, L.A.; Daly, J.W.; et al. A survey of non-xanthine derivatives as adenosine receptor ligands. Nucleos. Nucleotid. 1996, 15, 693–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parsons, W.J.; Ramkumar, V.; Stiles, G.L. The new cardiotonic agent sulmazole is an A1 adenosine receptor antagonist and functionally blocks the inhibitory regulator, Gi. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998, 33, 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda, M.A.; Stoddart, L.A.; Gherbi, K.; Briddon, S.J.; Kellam, B.; Hill, S.J. A non-imaging high throughput approach to chemical library screening at the unmodified adenosine-A3 receptor in living cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.A.; Moro, S.; Manthey, J.A.; West, P.L.; Ji, X.-D. Interaction of flavones and other phytochemicals with adenosine receptors. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2002, 505, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Braganhol, E.; Tamajusuku, A.S.K.; Bernardi, A.; Wink, M.R.; Battastini, A.M.O. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 inhibition by quercetin in the human U138MG glioma cell line. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2007, 1770, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Warnick, E.; Crane, S.; Gao, Z.G.; O’Connor, R.O.; Jacobson, K.A.; Carlsson, J. Structure-based screening of uncharted chemical space for atypical adenosine receptor agonists. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 2763–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amouzadeh, H.R.; Dimery, I.; Werner, J.; Ngarmchamnanrith, G.; Engwall, M.J.; Vargas, H.M.; Arrindell, D. Clinical implications and translation of an off-target pharmacology profiling hit: Adenosine uptake inhibition in vitro. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1296–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masino, S.A.; Li, T.; Theofilas, P.; Sandau, U.S.; Ruskin, D.N.; Fredholm, B.B.; Geiger, J.D.; Aronica, E.; Boison, D. A ketogenic diet suppresses seizures in mice through adenosine A1 receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2679–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Calker, D.; Biber, K. The role of glial adenosine receptors in neural resilience and the neurobiology of mood disorders. Neurochem. Res. 2005, 30, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varani, K.; Vincenzi, F.; Ravani, A.; Pasquini, S.; Merighi, S.; Gessi, S.; Setti, S.; Cadossi, M.; Borea, P.A.; Cadossi, R. Adenosine receptors as a biological pathway for the anti-inflammatory and beneficial effects of low frequency low energy pulsed electromagnetic fields. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzi, F.; Pasquini, S.; Setti, S.; Cadossi, M.; Borea, P.A.; Cadossi, R.; Varani, K. Pulsed electromagnetic fields mediate anti-inflammatory effects through adenosine receptor pathway in joint cells. Orthopaed. Proceed. 2018, 100, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | A1AR | A2AAR | A2BAR | A3AR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonists | ||||

| Adenosine 1 | ~100 73 (r) | 310 150 (r) | 15,000 5100 (r) | 290 6500 (r) |

| R-PIA 4 | 2.04 1.2 (r) | 220 (r) | 150,000 | 33 158 (r) |

| CGS21680 8 | 289 193 (m) | 27 10 (m) | >10,000 | 67 48 (m) |

| Regadenoson 9 | >16,000 7.75 (m) | 290 77.2 (m) | >10,000 >100,000 (m) | >10,000 >10,000 (m) |

| Bay60-6583 a 12 | >10,000 351 (m) | >10,000 >10,000 (m) | 3–10 136 (m) | >10,000 3920 (m) |

| IB-MECA 13 | 51 5.9 (m) | 2900 ~1000 (m) | 11,000 | 1.8 0.087 (m) |

| Cl-IB-MECA 14 | 220 35 (m) | 5360 ~10,000 (m) | >10,000 | 61.4 0.18 (m) |

| Antagonists | ||||

| Caffeine 23 | 10,700 | 24,300 | 33,800 | 13,300 >100,000 (r) |

| 8-SPT 24 | 537 (m) | 12,400 (m) | 4990 (m) | >10,000 (m) |

| XAC 25 | 6.8 1.2 (r), 2.2 (m) | 18.4 63 (r), 83 (m) | 7.75 63 (r), 4.5 (m) | 25.6 29,000 (r), ~10,000 (m) |

| DPCPX 26 | 3.0 1.5 (m) | 129 598 (m) | 51 86.2 (m) | 795 >10,000 (r, m) |

| CSC b | 28,000 (r) | 54 (r) | 8200 (r) | >10,000 (r) |

| SCH442416 28 | 1110 765 (m) | 4.1 1.27 (m) | >10,000 | >10,000 >10,000 (m) |

| ZM241385 32 | 774 249 (m) | 1.6 0.72 (m) | 75 31 (m) | 743 10,000 (m) |

| MRS1220 38 | 81 (m) | 9.1 (m) | ND | >10,000 (m) |

| 305 (r) | 52 (r) | ND | 0.65 (h) | |

| MRS1523 39 | >10,000 15,600 (r) 5330 (m) | 3660 2050 (r) >10,000 (m) | >10,000 >10,000 (m) | 18.9 113 (r) 702 (m) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacobson, K.A.; Reitman, M.L. Adenosine-Related Mechanisms in Non-Adenosine Receptor Drugs. Cells 2020, 9, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040956

Jacobson KA, Reitman ML. Adenosine-Related Mechanisms in Non-Adenosine Receptor Drugs. Cells. 2020; 9(4):956. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040956

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacobson, Kenneth A., and Marc L. Reitman. 2020. "Adenosine-Related Mechanisms in Non-Adenosine Receptor Drugs" Cells 9, no. 4: 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040956

APA StyleJacobson, K. A., & Reitman, M. L. (2020). Adenosine-Related Mechanisms in Non-Adenosine Receptor Drugs. Cells, 9(4), 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040956