Understanding Groundwater Mineralization Changes of a Belgian Chalky Aquifer in the Presence of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane Degradation Reactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Area

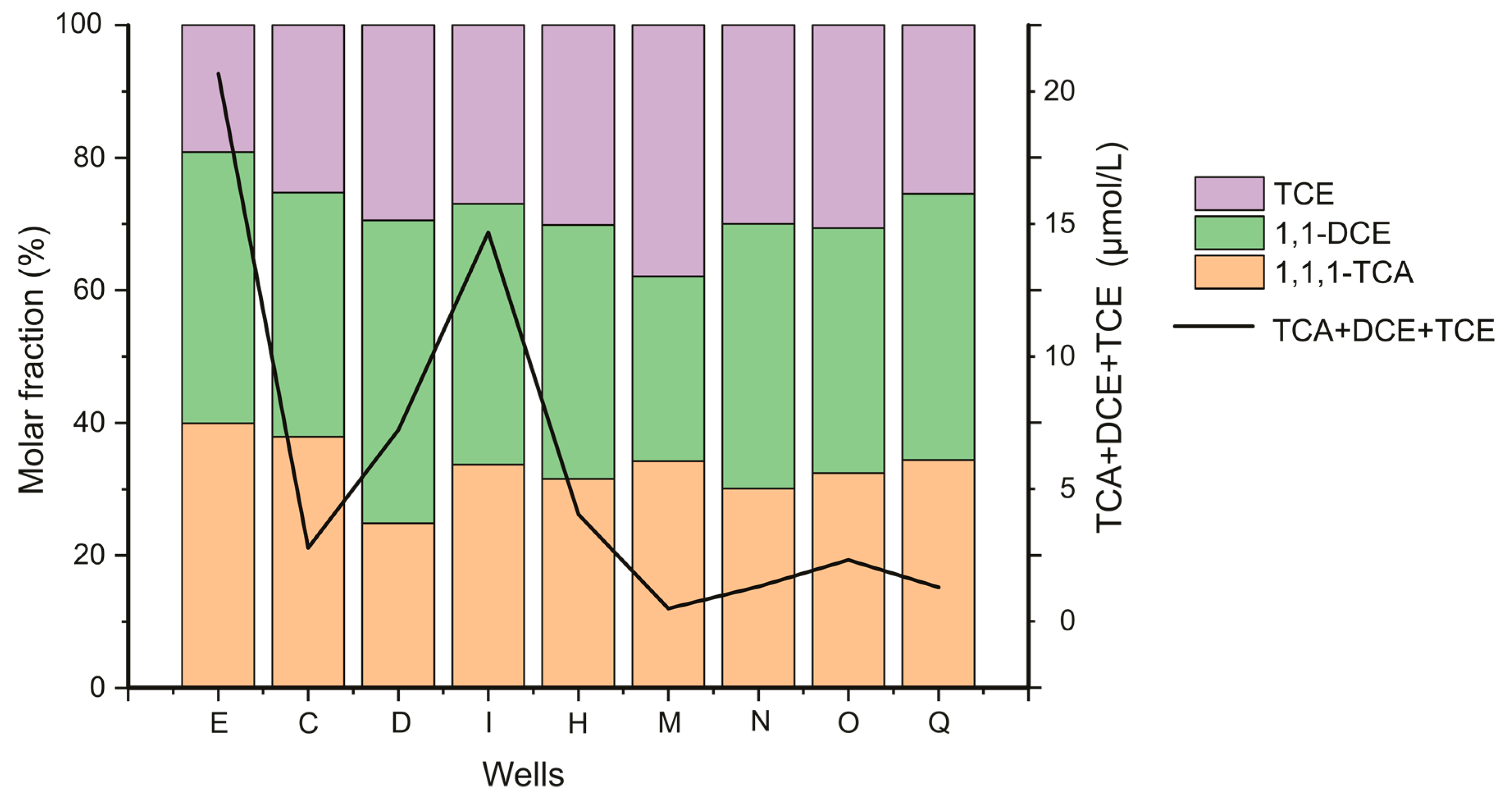

3. Groundwater Quality Investigations

3.1. Sampling and Analysis

- Ion chromatography for K+, Mg2+, Na+, NH4+, Li+, Sr2+, PO43−, Br− Cl−, F−, NO3− and SO42−;

- Titrimetric method for Ca2+;

- Flame atomic absorption for Fe3+, Mn2+ and SiO2;

- The Carbonate speciation between CO2, HCO3−, CO32− is obtained from pH and total alkanity; according to Rodier’s formula [30];

- Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC/MS) for the CAHs.

3.2. Simulation of Calcite Dissolution under Degradation Reactions

4. Tests and Analyses on Backfill Soil in the Source Area

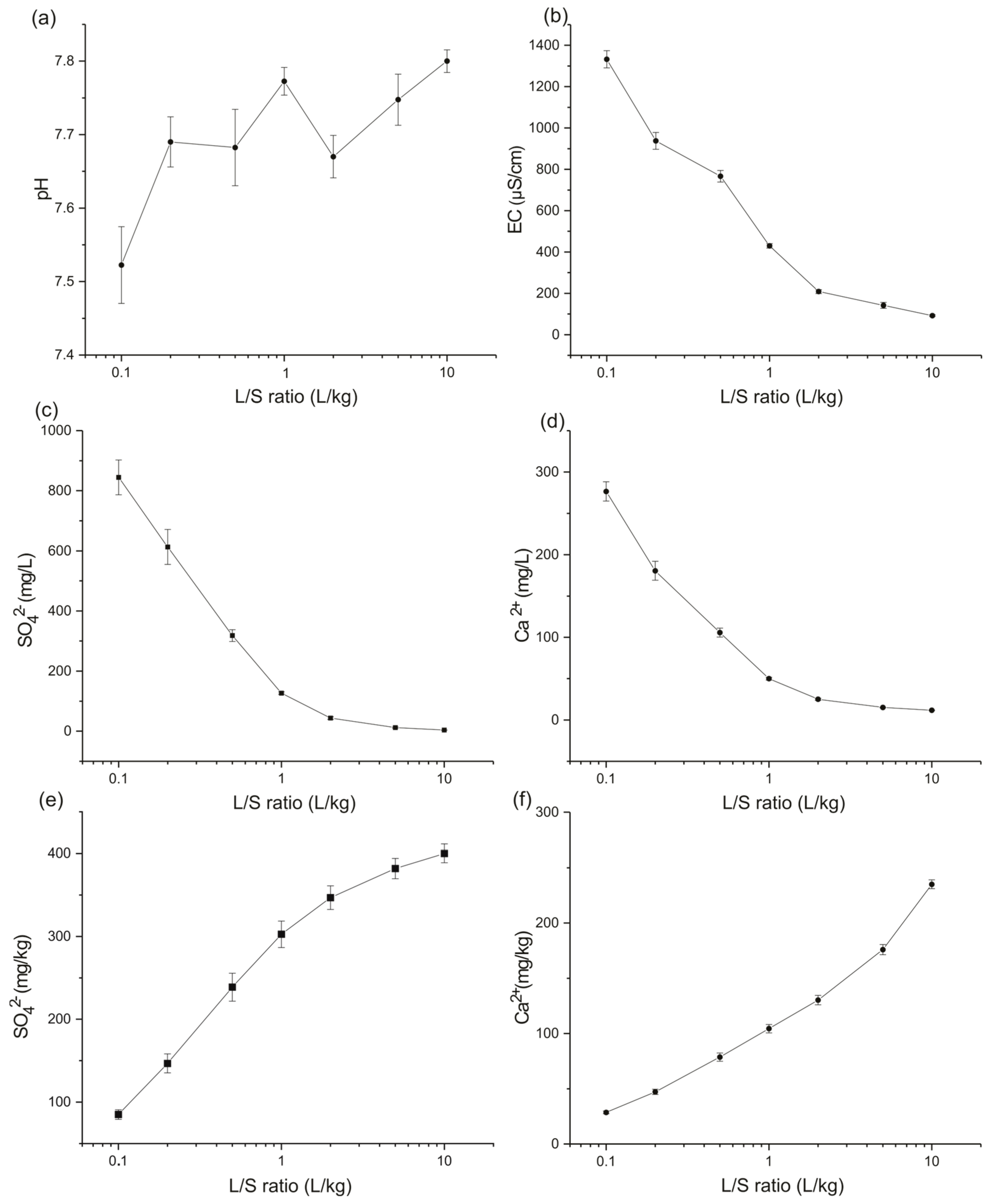

4.1. Leaching Test

Application at the Site Scale

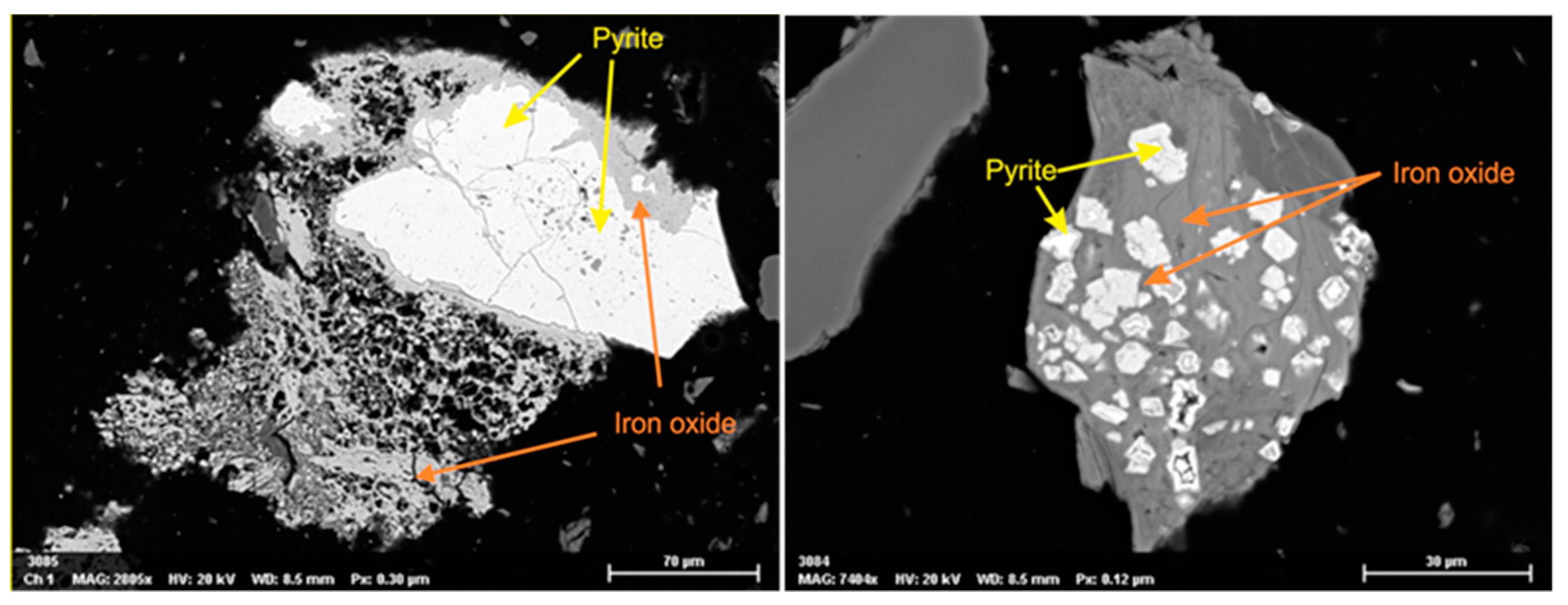

4.2. Mineralogical Analysis

5. δ34S and δ18O of SO42− in Backfill Eluates and in Groundwater

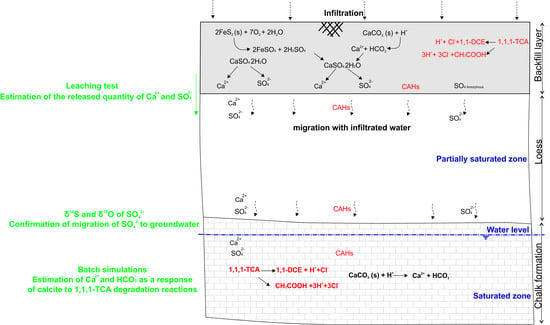

6. Synthesis of Process Leading to Groundwater Mineralization Changes

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Westrick, J.J.; Mello, J.W.; Thomas, R.F. The Groundwater Supply Survey. J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1984, 76, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.J. Description, Properties, and Degradation of Selected Volatile Organic Compounds Detected in Ground Water—A Review of Selected Literature. U.S. Geol. Surv. Open-File Rep. 2006, 2006–2133, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgo, J.J.W.; Nielsen, P.H.; Bannon, M.P.; Harrison, I.; Christensen, T.H. Effect of geochemical conditions on fate of organic compounds in groundwater. Environ. Geol. 1996, 27, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemeier, T.H.; Rifai, H.S.; Newell, C.J.; Wilson, J.T. Natural Attenuation of Fuels and Chlorinated Solvents in the Subsurface; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 9780470172964. [Google Scholar]

- Stroo, H.F.; Ward, C.H. (Eds.) In Situ Remediation of Chlorinated Solvent Plumes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 1441914013. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, F.H. The significance of microbial processes in hydrogeology and geochemistry. Hydrogeol. J. 2000, 8, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadpour-Keeley, A.; Keeley, J.W.; Russell, H.H.; Sewell, G.W. Monitored Natural Attenuation of Contaminants in the Subsurface: Processes. Groundw. Monit. Remediat. 2001, 21, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemeier, T.H.; Swanson, M.A.; Moutoux, D.E.; Gordon, E.K.; Wilson, J.T.; Wilson, B.H.; Kampbell, D.H.; Haas, P.E.; Miller, R.N.; Hansen, J.E. Technical protocol for evaluating natural attenuation of chlorinated solvents in groundwater. Cincinnatiohiousa: Usepa Natl. Risk Manag. Res. Lab. Off. Res. Dev. 1998. Available online: https://clu-in.org/download/remed/protocol.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Field, J.; Sierra-Alvarez, R. Biodegradability of chlorinated solvents and related chlorinated aliphatic compounds. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2004, 3, 185–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, R.E. A History of the Production and Use of Carbon Tetrachloride, Tetrachloroethylene, Trichloroethylene and 1,1,1-Trichloroethane in the United States: Part 2—Trichloroethylene and 1,1,1-Trichloroethane. Environ. Forensics 2000, 1, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, P.L. Biotic and abiotic transformations of chlorinated solvents in ground water. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Natural Attenuation of Chlorinated Organics in Ground Water, Dallas, TX, USA, 11–13 September 1996; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tobiszewski, M.; Namieśnik, J. Abiotic degradation of chlorinated ethanes and ethenes in water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 1994–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheutz, C.; Durant, N.D.; Hansen, M.H.; Bjerg, P.L. Natural and enhanced anaerobic degradation of 1,1,1-trichloroethane and its degradation products in the subsurface—A critical review. Water Res. 2011, 45, 2701–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.S.D.; Morris, B.L.; Chilton, P.J. Groundwater in urban development-a review of linkages and concerns. Iahs Publ. 1999, 259, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.S.D. The interdependence of groundwater and urbanisation in rapidly developing cities. Urban Water 2001, 3, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambel, A.; Duque, J.; Madeira, M.M. HYDROCHEMICAL QUALITY OF GROUNDWATER IN URBAN AREAS OF SOUTH PORTUGAL. In Urban Groundwater Management and Sustainability; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Bottrell, S.; Tellam, J.; Bartlett, R.; Hughes, A. Isotopic composition of sulfate as a tracer of natural and anthropogenic influences on groundwater geochemistry in an urban sandstone aquifer, Birmingham, UK. Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 2382–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, K.W. Urban Groundwater Issues—An Introduction. In Current Problems of Hydrogeology in Urban Areas, Urban Agglomerates and Industrial Centres; Howard, K.W.F., Israfilov, R.G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-94-010-0409-1. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, E. Methodological Manual: Management of Local Soil Pollution-Notice Méthodologique: Gestion de la Pollution Locale des sols (in French). Direction de l’Etat Environnemental (DEE)-Service Public de Wallonie (SPW). Available online: http://etat.environnement.wallonie.be/files/indicateurs/SOLS/SOLS 5/Notice_methodologique_Gestion pollution locale des sols.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Orban, P.; Brouyère, S.; Compère, J.; Six, S.; Hallet, V.; Goderniaux, P.; Dassargues, A. Aquifère crayeux de Hesbaye. In Watervoerende Lagen en Grondwater in Belgïe-Aquifères et eaux Souterraines en Belgique; Dassargues, A., Walraevens, K., Eds.; Academia Press: Gent, Belgium, 2014; partie 1-Chapitre 12; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Palau, J.; Jamin, P.; Badin, A.; Vanhecke, N.; Haerens, B.; Brouyère, S.; Hunkeler, D. Use of dual carbon-chlorine isotope analysis to assess the degradation pathways of 1,1,1-trichloroethane in groundwater. Water Res. 2016, 92, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission, E. Council Directive 98/83/EC of 3 November 1998 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1998, 41, 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brouyère, S.; Dassargues, A.; Hallet, V. Migration of contaminants through the unsaturated zone overlying the Hesbaye chalky aquifer in Belgium: A field investigation. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2004, 72, 135–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassargues, A.; Monjoie, A. The chalk in Belgium. In The Hydrogeology of the Chalk of North-West Europe; Downing, R.A., Price, M., Jones, G.P., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 153–269. ISBN 0198542852. [Google Scholar]

- Hallet, V. Etude de la Contamination de la Nappe Aquifere de Hesbaye par les Nitrates: Hydrogéologie, Hydrochimie et Modélisation (Contamination of the Hesbaye Aquifer by Nitrates: Hydrogeology, Hydrochemistry and Mathematical Modeling). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liege, Liege, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Orban, P. Solute Transport Modelling at the Groundwater Body Scale: Nitrate Trends Assessment in the Geer Basin (Belgium). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liege, Liege, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dassargues, A. Hydrogeology: Goundwater Science and Engineering; Taylor & Francis CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781498744003. [Google Scholar]

- Brouyère, S.; Hallet, V.; Dassargues, A. Effets de retard et de piégeage des polluants dus à la présence d’eau immobile dans le milieu souterrain: Importance de ces effets et modélisation. In Proceedings of the Nat. Colloquium van de BCIG/CBGI; KULeuven: Leuven, Belgium, 1997; pp. 21–27. Available online: https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/2363 (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. Description of input and Examples for PHREEQC Version 3: A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rodier, J.; Legube, B. L’analyse de l’eau; Dunod: Paris, France, 2009; ISBN 2100072463. [Google Scholar]

- Orban, P.; Brouyère, S.; Batlle-Aguilar, J.; Couturier, J.; Goderniaux, P.; Leroy, M.; Maloszewski, P.; Dassargues, A. Regional transport modelling for nitrate trend assessment and forecasting in a chalk aquifer. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2010, 118, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczucińska, A.; Dłużewski, M.; Kozłowski, R.; Niedzielski, P. Hydrochemical Diversity of a Large Alluvial Aquifer in an Arid Zone (Draa River, S Morocco). Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2019, 26, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiejaczka, Ł.; Prokop, P.; Kozłowski, R.; Sarkar, S. Reservoir’s Impact on the Water Chemistry of the Teesta River Mountain Course (Darjeeling Himalaya). Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2018, 25, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimblin, R.T. The chemistry and origin of groundwater in Triassic sandstone and Quaternary deposits, northwest England and some UK comparisons. J. Hydrol. 1995, 172, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkens, R.R.; Franklin, J.A. The rate of degradation of 1,1,1-trichloroethane in water by hydrolysis and dehydrochlorination. Chemosphere 1989, 19, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau, J.; Shouakar-Stash, O.; Hunkeler, D. Carbon and Chlorine Isotope Analysis to Identify Abiotic Degradation Pathways of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 14400–14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cline, P.V.; Delfino, J.J. Transformation kinetics of 1, 1, 1-trichloroethane to the stable product 1, 1-dichloroethene. In Biohazards of drinking water treatment; Larson, R.A., Ed.; Lewis Publishers, Inc.: Chelsea, MI, USA, 1989; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, T.D.; Murphy, B.L. Age Dating Groundwater Plumes Based on the Ratio of 1,1-Dichloroethylene to 1,1,1-Trichloroethane: An Uncertainty Analysis. Environ. Forensics 2003, 4, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization. CEN-TS 14405: Characterization of waste-Leaching behaviour tests-Up-flow percolation test (under specified conditions); CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO/TS 21268-3 Soil quality—Leaching procedures for subsequent chemical and ecotoxicological testing of soil and soil materials—Part 3: Up-flow percolation test; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Council, E.U. Council Decision 2003/33/EC of 19 December 2002 establishing criteria and procedures for the acceptance of waste at landfills persuant to Article 16 of and Annex II to Directive 1999/31/EC. Off. J. Eur. Commun. 2003, 16, L11. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.M.; Reynolds, R.C. X-ray Diffraction and the Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; Volume 322. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, A.A. TOPAS User’s Manual, Version 3.0; Bruker AXS GmbH: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stainier, X. Matériaux pour la faune du Houiller de Belgique (note 3). Available online: http://biblio.naturalsciences.be/rbins-publications/bulletin-de-la-societe-belge-de-geologie/007-1893/bsbg_07_1893_mem_p135-160.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- Ruthy, I.; Dassargues, A. Carte Hydrogéologique de Wallonie, Jehay-Bodegnée-Saint-Georges-sur-Meuse 41/7-8. Notice explicative: Première édition: Mai 2003-Actualisation partielle: Décembre 2010; Namur, Belgium, 2010. Available online: http://environnement.wallonie.be/cartosig/cartehydrogeo/document/Notice_4178.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Evangelou, V.P.; Zhang, Y.L. A review: Pyrite oxidation mechanisms and acid mine drainage prevention. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 25, 141–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancken, K.C.; Laethem, B. Recycling options for gypsum from construction and demolition waste. Waste Manag. Ser. 2000, 1, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B. Assessing sources and transformations of sulphate and nitrate in the hydrosphere using isotope techniques. In Isotopes in the Water Cycle; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado, A.; Borges, A.V.; Pujades, E.; Hakoun, V.; Otten, J.; Knöller, K.; Brouyère, S. Occurrence of greenhouse gases in the aquifers of the Walloon Region (Belgium). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouse, H.R.; Mayer, B. Sulphur and Oxygen Isotopes in Sulphate. In Environmental Tracers in Subsurface Hydrology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 195–231. [Google Scholar]

| Geological Material | Top of Formation (m Below Surface) | Bottom of Formation (m Below Surface) | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backfill layer | 0 | 1.5 | Loamy and sandy soil, with recycled construction materials, shale and coal waste | Heterogeneous backfill only at the industrial site |

| Loess | 1.5 | 4.8/10 | Loess, sandy and clayey loess | Variable thickness, higher thickness in piezometers located out of the contamination site |

| Flint conglomerate | 4.8/10 | 10/18 | Flint conglomerate in loamy and/or sandy and/or clayey matrix | / |

| Chalk | 10/18 | - | White chalk with observed fractured chalk in boreholes | Locally, the bottom of chalk was not reached. Average thickness 30 m from regional data mapping |

| Sample | Temperature (In Situ) (°C) | Dissolved Oxygen mg/L | pH (In Situ) - | EC (In Situ) µS/cm | Ca2+ mg/L | K+ mg/L | Mg2+ mg/L | Na+ mg/L | Cl− mg/L | NO3− mg/L | SO42− mg/L | HCO3− mg/L | SiO2 mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | 10.6 | 2.95 | 6.68 | 848 | 310.09 | 1.28 | 31.13 | 59.40 | 160.97 | 90.36 | 343.63 | 423.99 | 4.22 |

| P | 12.5 | 1.04 | 6.12 | 1525 | 255.46 | 1.15 | 21.07 | 65.69 | 94.73 | 57.99 | 301.15 | 426.27 | 10.25 |

| E | 11.8 | 2.82 | 6.27 | 1120 | 241.67 | 1.02 | 23.09 | 45.88 | 144.55 | 58.81 | 273.00 | 298.28 | 6.29 |

| A | 12.1 | 1.4 | 6.47 | 1847 | 304.43 | 0.93 | 27.20 | 86.56 | 125.40 | 47.13 | 370.35 | 528.95 | 11.42 |

| S-25 | 14.6 | 3.25 | 6.95 | 858 | 252.12 | 0.79 | 25.62 | 50.38 | 74.66 | 64.94 | 298.01 | 423.96 | 4.95 |

| S-40 | 14.9 | 3.19 | 7.11 | 914 | 203.86 | 0.99 | 18.36 | 41.98 | 65.64 | 76.83 | 144.96 | 423.90 | 5.13 |

| T | 15.1 | 4.71 | 7.25 | 1056 | 242.09 | 2.02 | 22.68 | 53.70 | 102.63 | 95.20 | 235.28 | 394.66 | 1.59 |

| D | 10.8 | 2.08 | 6.75 | 1110 | 227.43 | 0.77 | 20.43 | 37.23 | 60.44 | 50.61 | 208.97 | 444.67 | 4.56 |

| D_2 | 10.8 | 2.08 | 6.75 | 1110 | 226.86 | 0.80 | 20.26 | 36.58 | 59.99 | 51.27 | 207.79 | 449.26 | n.d. |

| I | 12.1 | 2.13 | 6.86 | 1190 | 189.58 | 0.81 | 17.83 | 24.93 | 61.73 | 47.06 | 133.61 | 393.23 | n.d. |

| H | 10.1 | 1.24 | 6.72 | 1293 | 208.41 | 1.00 | 20.01 | 37.11 | 68.40 | 75.68 | 161.21 | 415.20 | 12.54 |

| M | 9.2 | 4.08 | 6.9 | 787 | 173.14 | 1.07 | 18.16 | 22.36 | 49.41 | 68.03 | 99.50 | 387.72 | 13.75 |

| N | 11.3 | 3.1 | 6.83 | 1124 | 184.81 | 0.98 | 19.16 | 25.75 | 52.92 | 71.59 | 116.95 | 401.77 | n.d. |

| O | 10.5 | 3.75 | 6.6 | 1286 | 179.59 | 1.14 | 18.49 | 24.25 | 53.42 | 64.51 | 107.73 | 394.41 | 3.21 |

| Q | 12.2 | 3.47 | 6.45 | 1054 | 168.39 | 0.87 | 14.84 | 19.93 | 48.30 | 63.70 | 93.06 | 360.32 | 7.63 |

| 1,1,1-TCA | 1,1,1-TCA | Half Life | Degradation Time | Coefficient of HCl for 1 mol of 1,1,1-TCA | Concentration of Hydrochloric Acid | Initial pH | pH with Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µg/L | mol/L | year | year | - | mol/L | - | - |

| 200 | 1.50×10-6 | 11.57 | 1 | 2.46 × 0.043 | 1.59×10-7 | 7.07 | 6.61 |

| 300 | 2.25×10-6 | 11.57 | 1 | 2.46 × 0.043 | 2.38×10-7 | 7.07 | 6.49 |

| 500 | 3.75×10-6 | 11.57 | 1 | 2.46 × 0.043 | 3.96×10-7 | 7.07 | 6.32 |

| 1100 | 8.25×10-6 | 11.57 | 1 | 2.46 × 0.043 | 8.72×10-7 | 7.07 | 6.02 |

| 1,1,1-TCA | pH after Degradation | pH Equilibrium | Ca2+ | HCO3− | ∆ Ca2+ | ∆ HCO3− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µg/L | - | - | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L |

| Unpolluted water | 7.07 | - | 149.40 | 309.98 | - | - |

| 200 | 6.62 | 6.76 | 167.05 | 363.62 | 17.65 | 53.64 |

| 300 | 6.49 | 6.70 | 178.11 | 397.24 | 28.71 | 87.26 |

| 500 | 6.32 | 6.60 | 197.54 | 456.48 | 48.14 | 146.50 |

| 1100 | 6.02 | 6.42 | 244.68 | 599.91 | 95.28 | 289.93 |

| L/S Ratio (L/kg) | Estimated Time (Year) | SO42− Released Quantity (mg/kg) from the Test | SO42− Total Mass (kg) | SO42− Concentration in Water Recharge (mg/L) | Ca2+ Released Quantity (mg/kg) from the Test | Ca2+ Total Mass (kg) | Ca2+ Concentration in Water Recharge (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.86 | 84.98 | 197.70 | 849.79 | 28.56 | 66.45 | 285.62 |

| 0.2 | 1.72 | 146.67 | 341.23 | 733.36 | 47.20 | 109.81 | 236.01 |

| 0.5 | 4.29 | 238.71 | 555.35 | 477.41 | 78.58 | 182.81 | 157.15 |

| 1 | 8.59 | 302.52 | 703.82 | 302.52 | 104.39 | 242.87 | 104.39 |

| 2 | 17.18 | 346.80 | 806.83 | 173.40 | 130.26 | 303.05 | 65.13 |

| 5 | 42.94 | 381.85 | 888.37 | 76.37 | 175.91 | 409.25 | 35.18 |

| 10 | 85.88 | 400.05 | 930.71 | 40.00 | 235.01 | 546.76 | 23.50 |

| Samples | Quartz | Micas | Calcite | Plagioclase | Chlorite | Orthoclase | Kaolinite | Hematite | Amphibole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| 1 | 53.1 | 12.7 | 7.3 | 10.3 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| 2 | 49.7 | 15.4 | 10.8 | 8.2 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 49.7 | 14.4 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 48.1 | 14.8 | 12.3 | 8.3 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Average | 50.2 | 14.3 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Standard error | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boudjana, Y.; Brouyère, S.; Jamin, P.; Orban, P.; Gasparella, D.; Dassargues, A. Understanding Groundwater Mineralization Changes of a Belgian Chalky Aquifer in the Presence of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane Degradation Reactions. Water 2019, 11, 2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102009

Boudjana Y, Brouyère S, Jamin P, Orban P, Gasparella D, Dassargues A. Understanding Groundwater Mineralization Changes of a Belgian Chalky Aquifer in the Presence of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane Degradation Reactions. Water. 2019; 11(10):2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102009

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoudjana, Youcef, Serge Brouyère, Pierre Jamin, Philippe Orban, Davide Gasparella, and Alain Dassargues. 2019. "Understanding Groundwater Mineralization Changes of a Belgian Chalky Aquifer in the Presence of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane Degradation Reactions" Water 11, no. 10: 2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102009

APA StyleBoudjana, Y., Brouyère, S., Jamin, P., Orban, P., Gasparella, D., & Dassargues, A. (2019). Understanding Groundwater Mineralization Changes of a Belgian Chalky Aquifer in the Presence of 1,1,1-Trichloroethane Degradation Reactions. Water, 11(10), 2009. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11102009