The Safety Journey: Using a Safety Maturity Model for Safety Planning and Assurance in the UK Coal Mining Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

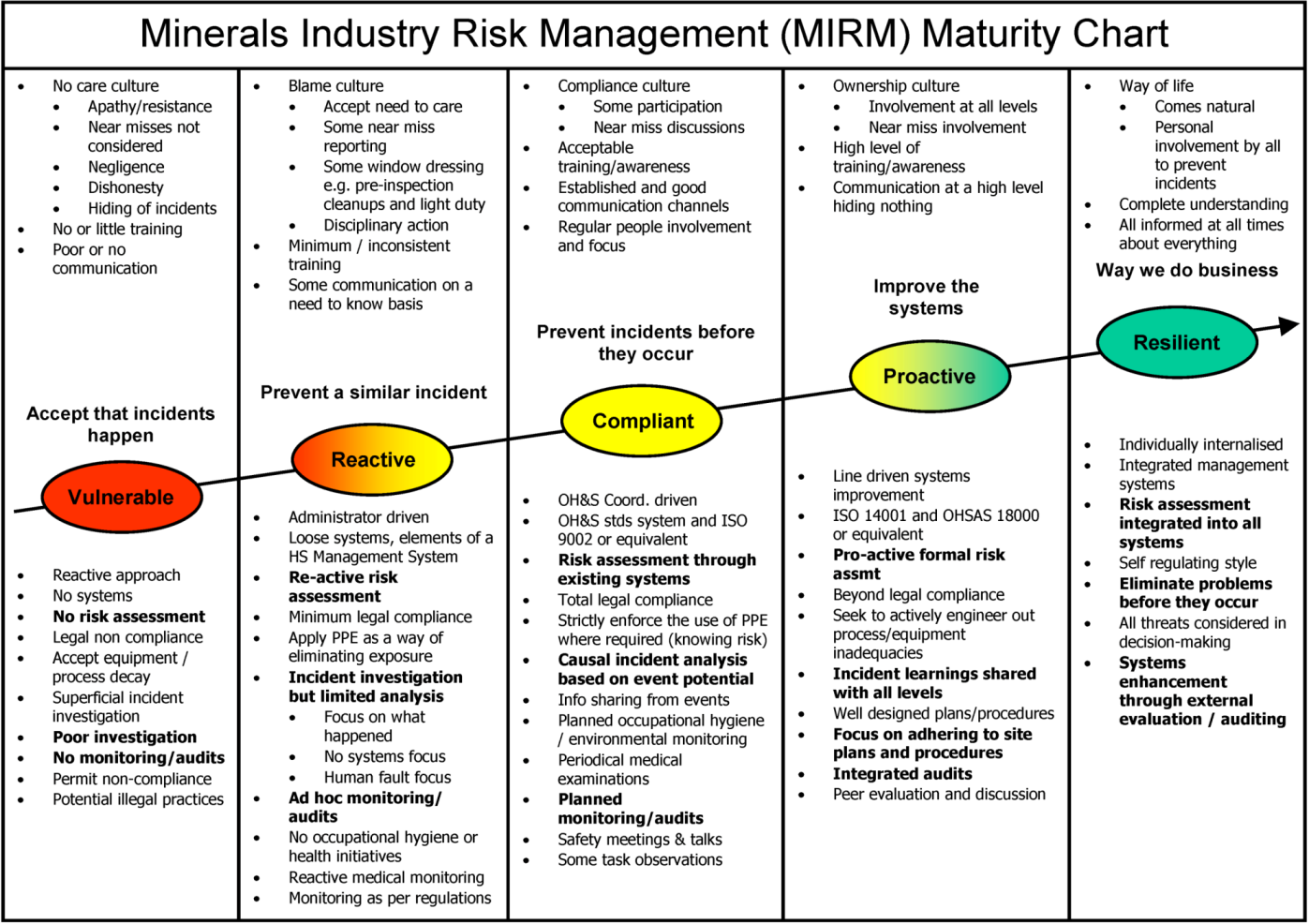

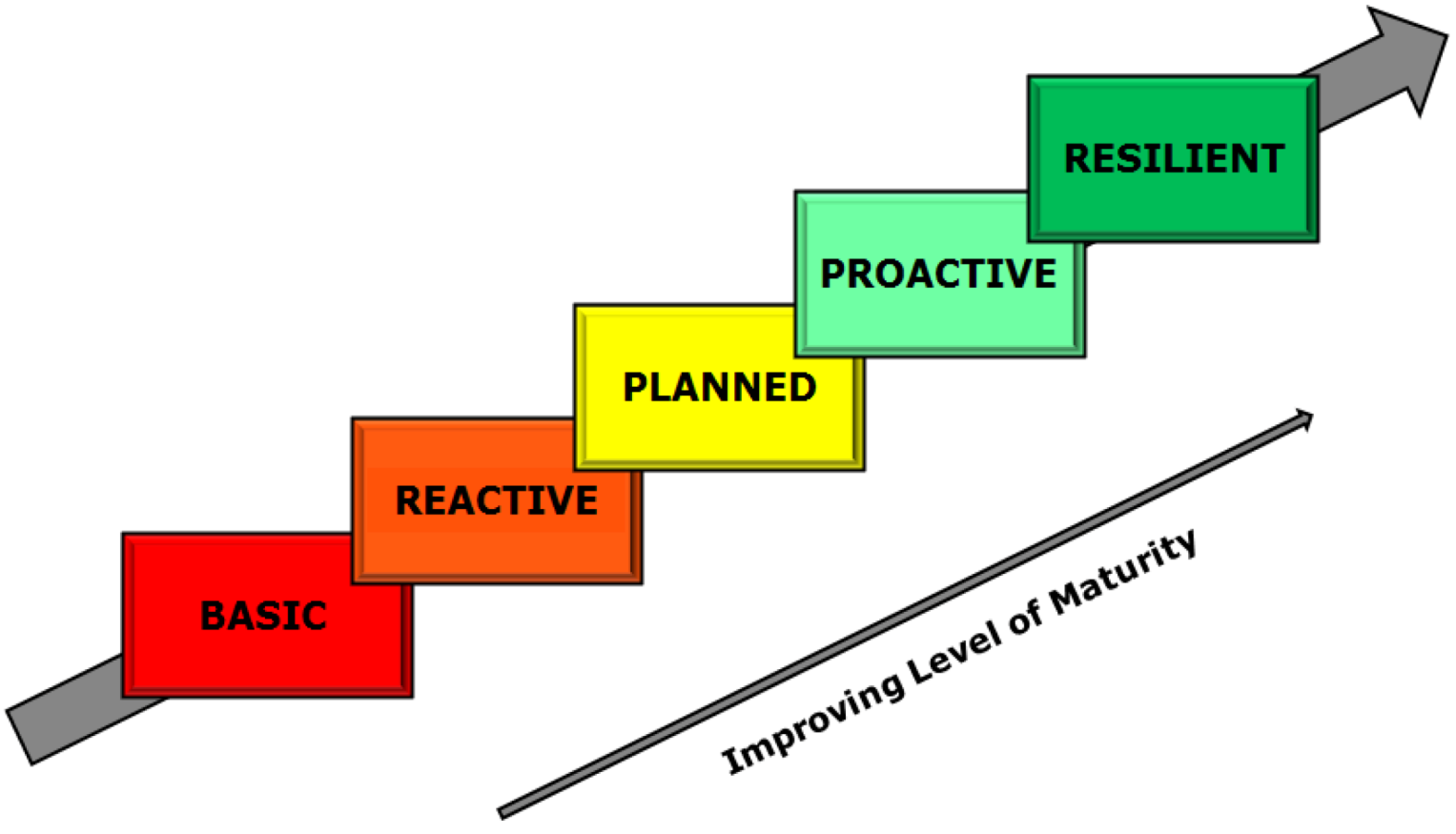

2. Safety Maturity Models

- Management commitment and visibility;

- Communications;

- Production versus Safety;

- Learning organization;

- Safety resources;

- Participation;

- Shaded perceptions about safety;

- Trust;

- Individual relations and job satisfaction.

- Pathological—Safety is a problem caused by workers. The main drivers are the business and a desire not to get caught by the regulator.

- Reactive—Organisations start to take safety seriously but there is only action after incidents.

- Calculative—Safety is driven by management systems, with much collection of data. Safety is still primarily driven by management and imposed rather than looked for by the workforce.

- Proactive—With improved performance, the unexpected is a challenge. Workforce involvement starts to move the initiative away from a purely top down approach.

- Generative—There is active participation at all levels. Safety is perceived to be an inherent part of the business. Organisations are characterised by chronic unease as a counter to complacency.

| “Concrete” Elements | “Abstract” Elements |

|---|---|

| Benchmarking, Trends & Statistics | Who causes accidents in the eyes of management? |

| Audits & Reviews | What happens after an accident? Is the feedback Loop being closed? |

| Incident/Accident Reporting, Investigation & Analysis; | |

| Hazard and Unsafe Act reports | How do safety meetings feel? |

| Work planning including PTW, Journey Management | Balance between HSE & Profitability? |

| Contractor Management | Is management interested in communicating HSE issues with the workforce? |

| Competency/Training | |

| Work-site Job Safety Techniques | Commitment level of the workforce and level of care for colleagues. |

| Who Checks Safety on a day to day basis? | |

| What is size & status of the HSE Department? | What is the purpose of procedures? |

| What are the rewards of good safety performance? |

3. The Use of Safety Maturity Models in the Mining Industry

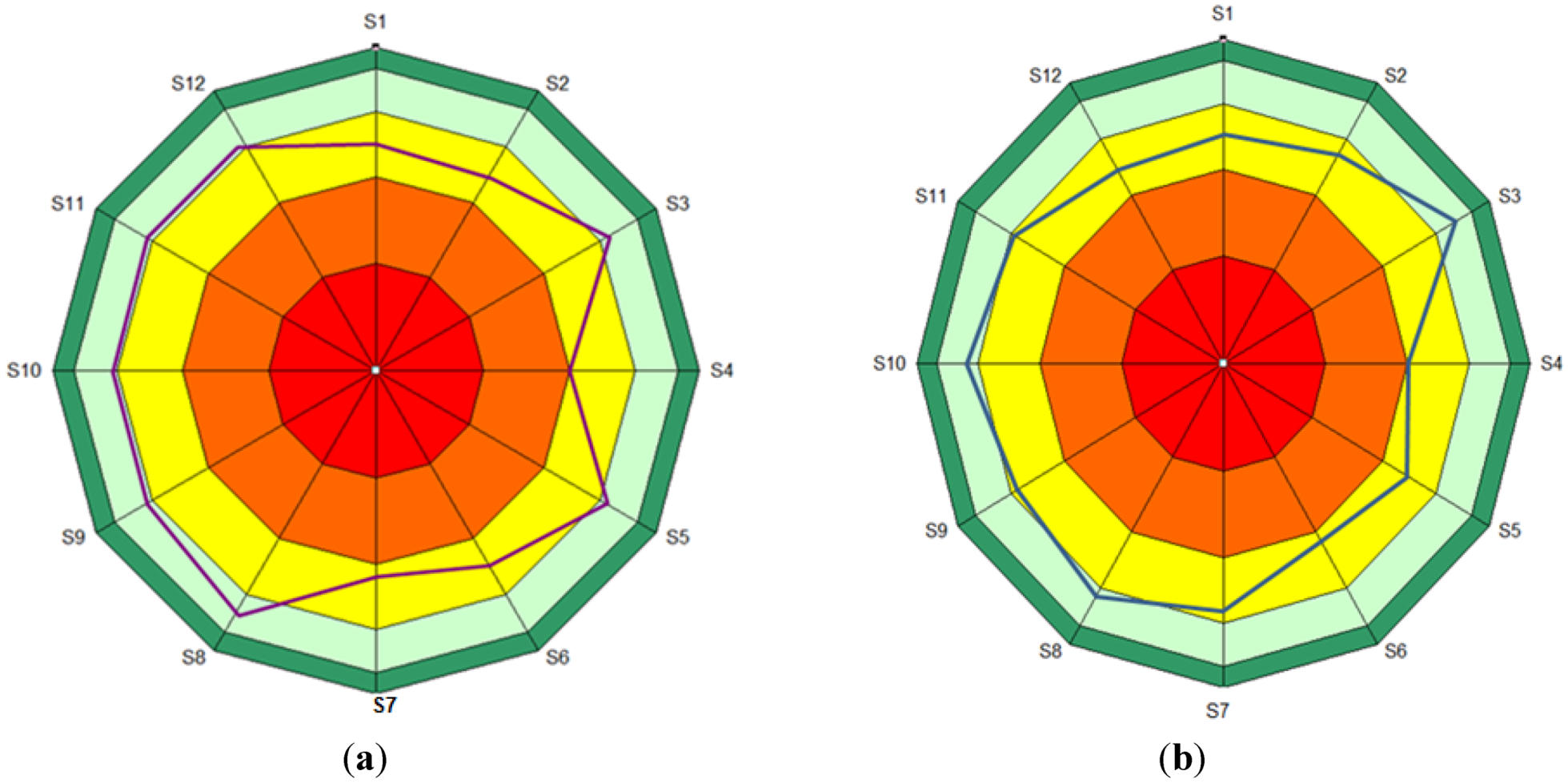

4. Development of a Safety Maturity Model for UK Coal

4.1. The UK Coal Safety Way

4.2. Development of the Methodology

| UK Coal Safety Way Element | Question Set |

|---|---|

| 1. Leadership & Accountability |

|

| 2. Policy & Commitment |

|

| 3. Risk & Change Management |

|

| 4. Legal Requirements |

|

| 5. Objectives, Targets & Performance Measurement |

|

| 6. Training, Competence & Awareness |

|

| 7. Communication & Consultation |

|

| 8. Control of Documents |

|

| 9. Operational Controls |

|

| 10. Emergency Procedures |

|

| 11. Incident Investigation |

|

| 12. Monitoring, Auditing & Reviews |

|

4.3. Trialing the Methodology

- Each site shall establish a measurable safety plan, quantifying corporate objectives and targets and site objectives and targets which shall be agreed by site personnel and corporate personnel. Objectives and targets shall be in line with the general target of enabling continual improvement of health and safety performance.

- Measurement against the plan shall form part of the site and corporate safety accountability process.

- Objectives and targets shall be communicated and understood by all appropriate personnel, including the Executive, Senior Management, line management, employees and contractors.

- Adequate resources shall be assigned to ensure that the planned and agreed targets and objectives are met.

- Senior management shall be issued with Safety Performance Indicators. Safety performance shall be part of those indicators to ensure that safety is a priority for management.

- UK Coal shall ensure that objectives and targets are reviewed on a periodic basis to ensure they stay on programme and to agree changes when they do not.

- Targets and objectives shall be both reactive—accidents, incidents and dangerous occurrences—and proactive—near hits, etc. and where appropriate, performance measures including benchmarking against established best practice.

- The organisation and all sites will be responsible for the effective review of objectives, targets and performance indicators to ensure they remain relevant for the current safety risk.

| Basic | Reactive | Planned | Proactive | Resilient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1. Setting of Targets | |||||

| Little evidence of safety related activities. Formal safety goals and objectives have not been identified, let alone documented. | Safety goals are based around improving safety performance, based on statistics from the previous year. | Some safety targets related to improving standards or systems are undertaken, but actions for this mainly apply to the safety department. | Senior Managers are involved in determining safety objectives in conjunction with the safety department | Every worker in the organization is accountable for specific risk control activities. | |

| This is set site-wide with a site plan established by the safety department that is passed around the senior management team, but not well communicated to the rest of the workforce. | Roles and activities are clearly defined for all levels in the site. | ||||

| All targets are determined by the Safety department and sanctioned by Senior Management. | |||||

| Work teams independently establish their own work objectives. | |||||

| 5.2. Monitoring & Accountability | |||||

| There is no accountability as nothing has been set. | Accountability is weak and progress is rarely reviewed throughout the year but the safety department is held accountable for results. | Monitoring is carried out by the Safety department who also becomes accountable for actions and activities related to the safety management system. | Line managers and supervisors are held accountable for results. | The safety performance indicators are proactive, and a performance monitoring system is in place focusing on operational excellence. | |

| Safety initiatives/ activities are adequately resourced and action plans/ objectives are set and monitored. | |||||

| Accountability is split between safety and line management depending on the results. | |||||

| Element | Basic | Reactive | Planned | Proactive | Resilient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Leadership & Accountability | - | 8% | 50% | 38% | 4% |

| 2. Policy & Commitment | - | 8% | 50% | 42% | - |

| 3. Risk & Change Management | - | - | 33% | 42% | 25% |

| 4. Legal Requirements | - | 33% | 50% | 17% | - |

| 5. Objectives & Perf Measurement | - | - | 58% | 42% | - |

| 6. Training, Competence & Awareness | - | - | 75% | 17% | 8% |

| 7. Communication & Consultation | - | - | 42% | 58% | - |

| 8. Control of Documents | - | - | 17% | 83% | - |

| 9. Operational Controls | - | - | 33% | 63% | 4% |

| 10. Emergency Procedures | - | - | 17% | 58% | 25% |

| 11. Incident Investigation | - | - | 50% | 37% | 13% |

| 12. Monitoring, Auditing & Reviews | - | 8% | 42% | 50% | - |

| Standard/Element | Required Changes | Specific Actions | As Measured by | Responsibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Leadership & Accountability (1.3 Rewards of Good Safety Performance) | Promote/celebrate significant safety achievements. | Newsletter | Accident free stats | Safety Department | |

| Screen in concourse. | Specific Work Standards Achievements | Line Management | |||

| HR Manager | |||||

| 2. Policy & Commitment (2.1 Safety Accountability) | Utilize front line supervisors to drive safety and “buy in” to safety. | Managers Weekly Meeting with Officials | Observation | Line Management | |

| Auditing | |||||

| Engineers weekly meeting | |||||

| Safety Accountability meeting | |||||

| 2. Policy & Commitment (2.4 Status of the Safety Function) | Clearer defined roles and responsibilities plus expectations within the mine management structure | HQ/Colliery Manager consultation | Compliance to Colliery Safety Action Plan | HQ/Colliery Manager | |

| Align to UK Coal Safety Policy | |||||

| 4. Legal Requirements (4.1 Awareness of Legal Requirements) | HQ Informing all line management in new/changes to legislation | Email line managers bulletin with changes to legislation | Compliance to all legislation, company directives & codes & rules | HQ/Colliery Manager | |

| Refresher updates for line management (away from pit) | |||||

| 7. Communication & Consultation (1. Communications) | Two way communication between management & workforce | Face & Development start up meetings | Testing Knowledge | Line Management | |

| All other meetings | Observations |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Fleming, M. Safety Culture Maturity Model; HSE Offshore Technology Report 2000/049: Sudbury, UK, 2000; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P. Implementing a safety culture in a major multi-national. Safety Sci. 2007, 45, 697–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.; Kirwan, B.; Perrin, E. Measuring safety culture in a research & development centre: A comparison of two methods in the air traffic management domain. Safety Sci. 2007, 45, 669–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil Centre, Managing Safety Culture in the UK Rail Industry: Report on the Review of Safety Culture Tools and Methods; Rail Safety & Standards Board: London, UK, 2004.

- Kyriakidis, M.; Hirsch, R.; Majumdar, A. Metro railway safety: An analysis of accident precursors. Safety Sci. 2012, 50, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardner, R. Towards a Mature Safety Culture. In Presented at the Institute of Chemical Engineers Annual Conference, Manchester, UK; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, A.P.G.; Andrade, J.C.S.; de Oliveira Marinho, M.M. A safety culture maturity model for petrochemical companies in Brazil. Safety Sci. 2010, 48, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Lardner, R. Safety culture—The way forward. Chem. Eng. 1999, 689, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P. Applying the lessons of high risk industries to health care. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2003, 12, i7–i12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Lawrie, M.; Hudson, P. A framework for understanding the development of organisational safety culture. Safety Sci. 2006, 44, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reducing Error and Influencing Behavior, 2nd ed; Health and Safety Executive: Sudbury, UK, 1999.

- Changing Minds: A Practical Guide for Behavioural Change in the Oil & Gas Industry. Step Change in Safety Website. Available online: http://www.stepchangeinsafety.net/knowledgecentre/publications/publication.cfm/publicationid/16 (accessed on 14 November 2012).

- Department of Resources, Energy & Tourism. Leading Practice Sustainable Development Practice for the Mining Industry: Risk Assessment & Management; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2008; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, J. Minerals Industry Safety & Health Centre, University of Queensland. Personal Communication, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The University of Queensland, Minerals Industry Risk Management Maturity Chart. University of Queensland Minerals Industry Health & Safety Centre: Brisbane, Australia, 2008.

- Detailed Journey Workbook, part of the A3 Safety Risk Management Process Training Material, Internal Document. Anglo American Plc: London, UK, 2010.

- UK Coal Plc. Annual Reports & Accounts 2011. Available online: http://coalfieldresources.com/uploads/assets/pdf/625_ukcoalplc2011bookmarked.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2013).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Foster, P.; Hoult, S. The Safety Journey: Using a Safety Maturity Model for Safety Planning and Assurance in the UK Coal Mining Industry. Minerals 2013, 3, 59-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/min3010059

Foster P, Hoult S. The Safety Journey: Using a Safety Maturity Model for Safety Planning and Assurance in the UK Coal Mining Industry. Minerals. 2013; 3(1):59-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/min3010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoster, Patrick, and Stuart Hoult. 2013. "The Safety Journey: Using a Safety Maturity Model for Safety Planning and Assurance in the UK Coal Mining Industry" Minerals 3, no. 1: 59-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/min3010059

APA StyleFoster, P., & Hoult, S. (2013). The Safety Journey: Using a Safety Maturity Model for Safety Planning and Assurance in the UK Coal Mining Industry. Minerals, 3(1), 59-72. https://doi.org/10.3390/min3010059