Biohydrogen Production by the Thermophilic Bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus: Current Status and Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Isolation and Initial Characterization

3. Hydrolytic Capacity and Complex Biomass Decomposition

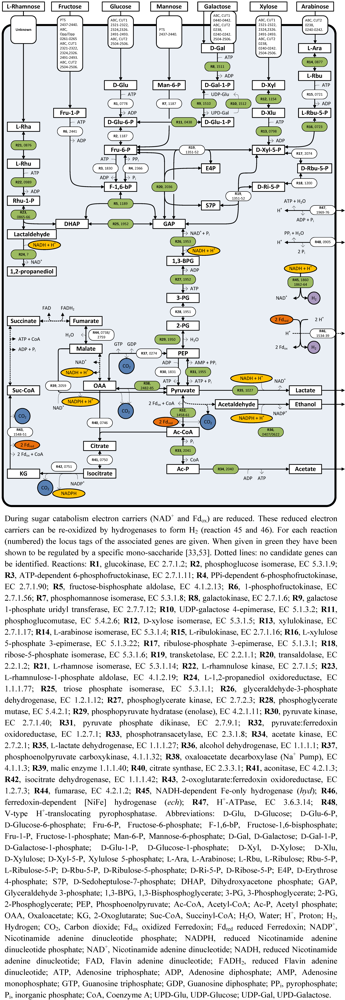

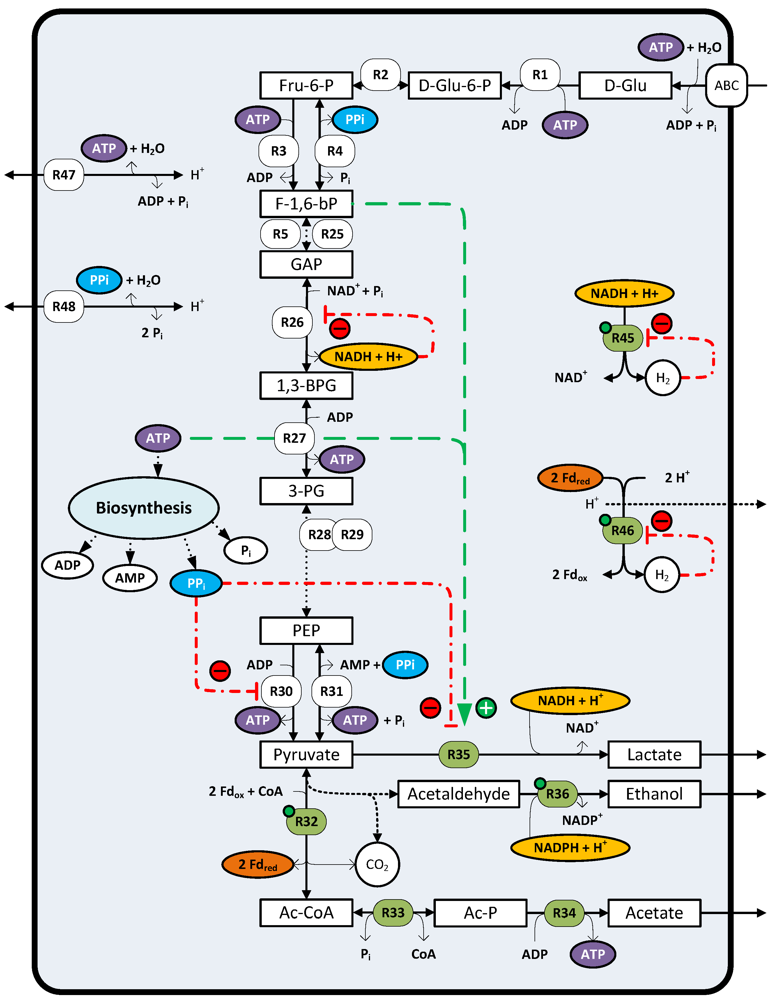

4. Sugar Catabolism and Pathway Regulation

4.1. Sugar Uptake and Fermentation

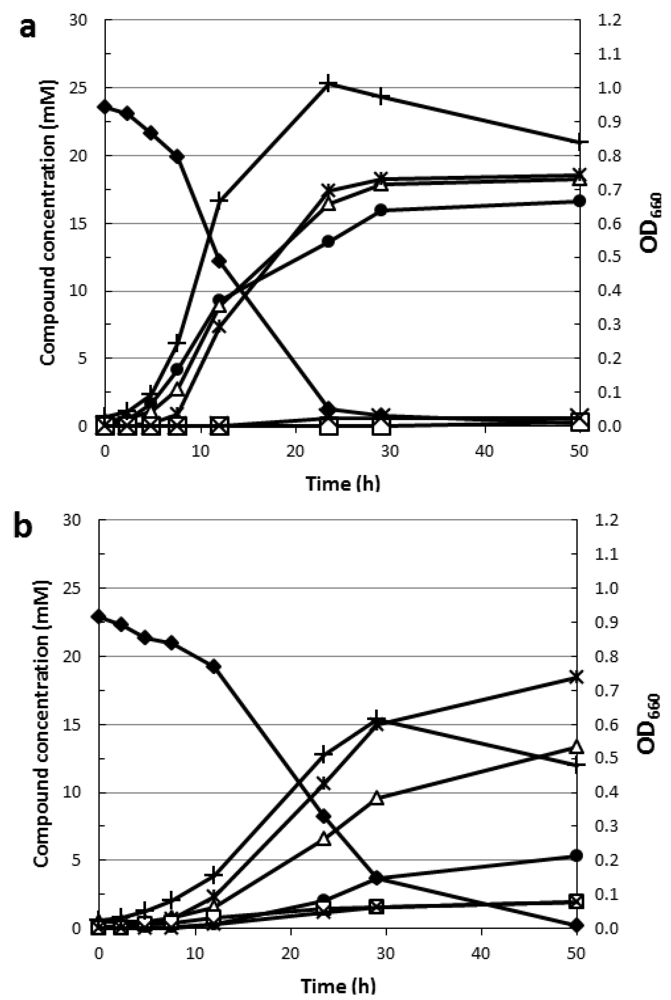

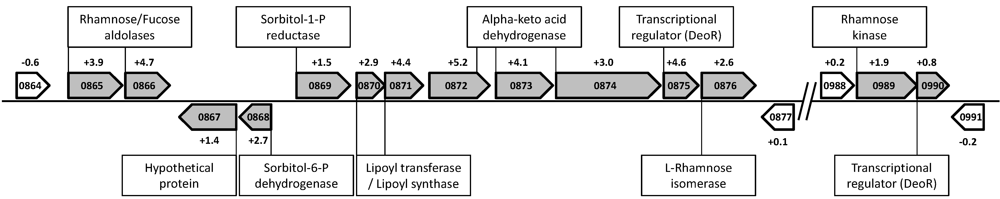

4.2. Rhamnose Fermentation

| Strain | Growth on Rhamnose | Gene cluster Csac_0865-76 | Gene cluster Csac_0989-90 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. saccharolyticus | + | + | + | [13] |

| C. bescii | + | + | + | [28] |

| C. owensensis | + | + | + | [21] |

| C. obsidiansis | nt | + | + | [20] |

| C. kronotskyensis | nt | + | + | [22] |

| C. hydrothermalis | nt | + | + | [22] |

| C. kristjanssonii | − | − | − | [17] |

| C. lactoaceticus | − | − | − | [23] |

| C. acetigenus | nt | ns | ns | [26] |

4.3. Involvement of Pyrophosphate in the Energy Metabolism

4.4. Mechanism Involved in Mixed Acid Fermentation

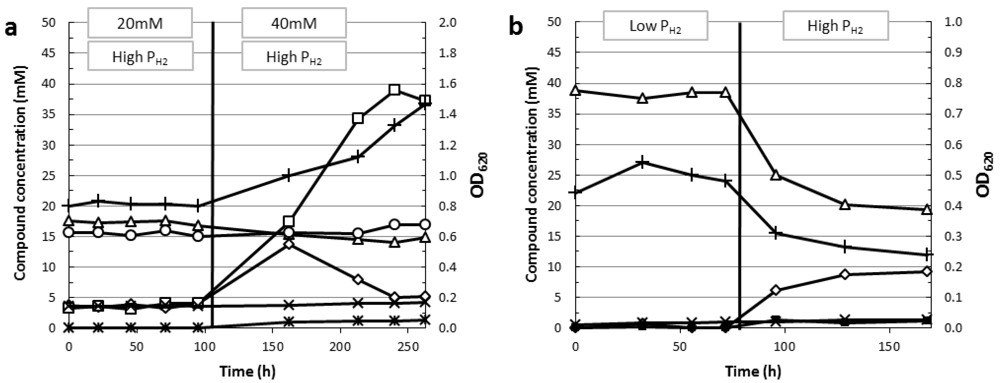

4.5. Regulation of Reductant Disposal Pathways

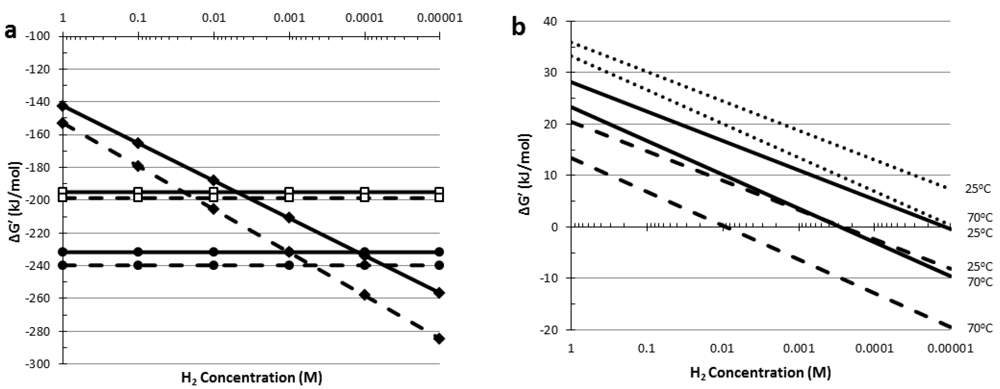

5. Thermodynamic Considerations of Glucose Conversion and H2 Formation

6. Factors Limiting H2 Formation

| Reference | Substrate | Pre-treatment * | Cultivation method | H2 yields $/Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [87] | Wheat grains | Enzymatic | B | |

| Wheat straw | Acid/Enzymatic | B | ||

| [88] | Barley straw | Acid/Enzymatic ** | B | |

| [29] | Crystalline cellulose | - | B | Proteome data |

| Birchwood xylan | - | B | ||

| Switchgrass | Acid | B | ||

| Whatman no. 1 filterpaper | - | B | ||

| [89] | Wheat straw | Acid/Enzymatic | B | |

| Barley straw | Acid/Enzymatic | B | ||

| Corn stalk | Acid/Enzymatic | B | ||

| Corn cob | Acid/Enzymatic | B | ||

| [36] | Poplar | - | B | Microarray data |

| Switchgrass | Acid | B | Microarray data | |

| [90] | Beet Molasses | - | CB | 0.9–4.2 |

| [91] | Potato steam peels | Enzymatic | CB | 1.7–3.4 |

| Potato steam peels | - | CB | 1.1–3.5 | |

| [92] | Filter paper | - | B | |

| Wheat straw | Biological | B | ||

| Silphium perfoliatum leaves | Biological | B | ||

| Maize leaves | Biological | B | ||

| Sugar cane bagasse | Biological | B | ||

| Sweet sorghum whole plant | Biological | B | ||

| [93] | Sugar beet | - | CB | 3.0 |

| [94] | Sweet sorghum bagasse | Alkaline/Enzymatic ** | B/CB | 1.3–2.6 |

| [55] | Carrot pulp | Enzymatic | CB | 1.3–2.8 |

| Carrot pulp | - | CB | ||

| [35] | Crystalline cellulose | - | B | Proteome data |

| Cellobiose | - | B | Microarray data | |

| [95] | Switchgrass | - | B | |

| Poplar | - | B | ||

| [53] | Xylan | - | B | Microarray data |

| Xyloglucan | - | B | Microarray data | |

| Xyloglucan-oligosaccharides | - | B | Microarray data | |

| [96] | Barley straw | Acid/Enzymatic | B | |

| Corn stalk | Acid/Enzymatic | B | ||

| Barley grain | Enzymatic | B | ||

| Corn grain | Enzymatic | B | ||

| Sugar beet | - | B | ||

| [97] | Sweet sorghum plant | - | B | |

| Sweet sorghum juice | - | B | ||

| Dry sugarcane bagasse | - | B | ||

| Wheat straw | - | B | ||

| Maize leaves | - | B | ||

| Maize leaves | Biological | B | ||

| Silphium trifoliatum leaves | - | B | ||

| [54] | Miscanthus giganteus | Alkaline/Enzymatic | B/CB | 2.4–3.4 |

| [52] | Agarose | - | B | With different support matrixes |

| Alginic acid | - | B | ||

| Pine wood shavings | - | B | ||

| [98] | Jerusalem artichoke | - | B | Co-fermentation with natural biogas-producing consortia |

| Fresh waste water sludge | - | B | ||

| Pig manure slurry | - | B | ||

| [78] | Paper sludge | Acid/Enzymatic | CB | |

| [99] | Paper sludge | Acid/Enzymatic | B |

| Reference | Substrate | Substrate | H2 Yield * | Productivity ** | Cultivation method | Dilution rate (h−1) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| load (g/L) | (mmol/(L*h)) | ||||||

| [100] | Glucose | 10 | 3.0 | 20.0 mol/(g*h) | CB | ||

| 10 | 3.4 | 23.6 mol/(g*h) | CB | No YE in medium | |||

| 4 | 3.5 | 10.1 mol/(g*h) | Chem | 0.05 | |||

| 4 | 3.5 | 10.4 mol/(g*h) | Chem | 0.05 | No YE in medium | ||

| [75] | Glucose | 5 | 3.5 | 5.2 | Chem | 0.05 | |

| 5 | 2.9 | 11.0 | Chem | 0.15 | Residual glucose (3 mM) | ||

| 5 | 1.8 | 2.5 | Chem | 0.05 | no sparging, open gas outlet | ||

| 5 | wash out | wash out | Chem | 0.15 | no sparging, open gas outlet | ||

| [101] | Glucose | 5 | nd | nd | B | Extracellular proteome | |

| [91] | Glucose | 10 | 3.4 | 12.0 | CB | ||

| 31 | 2.8 | 12.9 | CB | Residual glucose | |||

| [93] | Sucrose | 10 | 2.9 | 7.1 | CB | ||

| [94] | Glucose/Xylose/Sucrose | 10 | 3.2 | 10.7 | CB | Sugar mix | |

| (6:2.5:1.5, w/w/w) | 20 | 2.8 | 9.4 | CB | Sugar mix | ||

| [55] | Glucose | 10 | 3.2 | 11.2 | CB | ||

| 20 | 3.4 | 12.2 | CB | ||||

| Fructose | 10 | 2.6 | 13.2 | CB | |||

| 20 | 2.4 | 13.4 | CB | ||||

| Glucose/Fructose | 10 | 3.0 | 13.2 | CB | Sugar mix | ||

| (7:3, w/w) | 20 | 2.6 | 12.2 | CB | Sugar mix | ||

| [35] | Xylose | 5 | nd | nd | B | Proteome data | |

| Glucose | 5 | nd | nd | B | Proteome data | ||

| [50] | Glucose | 5 | nd | nd | B | Extracellular proteome | |

| [79] | Sucrose | 4 | 2.7 | 23.0 | CB | ||

| 4 | 3.1 | 11.8 | CB | CO2 sparging | |||

| Glucose | 4 | 3.0 | 20.0 | CB | |||

| 4 | 2.7 | 12.0 | CB | CO2 sparging | |||

| [53] | Glucose | 0.5 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data | |

| Mannose | 0.5 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data | ||

| Arabinose | 0.5 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data | ||

| Xylose | 0.5 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data | ||

| Fructose | 0.5 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data | ||

| Galactose | 0.5 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data | ||

| mix (0.5 g/L each) | 3 | nd | nd | B | Microarray data, Sugar mix | ||

| [54] | Glucose/Xylose | 10 | 3.4 | 12.0 | CB | Sugar mix | |

| (7:3 w/w) | 14 | 3.3 | 10.1 | CB | Sugar mix | ||

| 28 | 2.4 | 9.7 | CB | Sugar mix | |||

| [102] | Sucrose | 10.3 | 2.8 | 22.0 | Trickle bed | 0.2–0.3 | 400 L, non-axenic fermentation |

| [33] | Glucose | 4 | nd | nd | CB | Microarray data | |

| Xylose | 4 | nd | nd | CB | Microarray data | ||

| Rhamnose | 4 | nd | nd | CB | Microarray data | ||

| Glucose/Xylose (1:1, w/w) | 4 | nd | nd | CB | Microarray data | ||

| [56] | Glucose | 4.4 | 3.3 | 4.2 | Chem | 0.05 | |

| 4.4 | 3.6 | 8.9 | Chem | 0.10 | |||

| 4.4 | 2.9 | 9.5 | Chem | 0.15 | Residual glucose (3.3 mM) | ||

| 4.4 | 2.9 | 9.1 | Chem | 0.20 | Residual glucose (8.9 mM) | ||

| 4.4 | 3.1 | 11.0 | Chem | 0.30 | Residual glucose (12.4 mM) | ||

| 4.4 | 3.0 | 12.4 | Chem | 0.35 | Residual glucose (12.7 mM) | ||

| 1.9 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Chem | 0.09 | |||

| 1.9 | 3.3 | 9.9 | Chem | 0.30 | Residual glucose (0.6 mM) | ||

| 4.1 | 3.5 | 7.7 | Chem | 0.09 | |||

| 4.1 | 3.1 | 11.6 | Chem | 0.30 | Residual glucose (11.9 mM) | ||

| [78] | Glucose | 10 | 2.5 | 10.7 | CB | ||

| Xylose | 10 | 2.7 | 11.3 | CB | |||

| Glucose/Xylose (11:3, w/w) | 8.4 | 2.4 | 9.2 | CB | Sugar mix | ||

| [103] | Sucrose | 10 | 3.3 | 8.4 | CB |

6.1. Comparison between Hydrolysates and Pure Sugar Mixtures

6.2. Incomplete Substrate Conversion

6.3. End Product Inhibition and Osmotolerance

6.4. Medium Requirements

7. Future Prospects for Improving Biohydrogen Production

7.1. Improving H2 Yields and H2 Productivity

7.2. Genetic Engineering of Caldicellulosiruptor Species

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Supplementary Files

References and Notes

- Lynd, L.R.; Wyman, C.E.; Gerngross, T.U. Biocommodity engineering. Biotechnol. Prog. 1999, 15, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Zyl, W.H.V.; McBride, J.E.; Laser, M. Consolidated bioprocessing of cellulosic biomass: An update. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbor, V.B.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Berlin, A.; Levin, D.B. Biomass pretreatment: Fundamentals toward application. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.G.; McBride, J.E.; Shaw, A.J.; Lynd, L.R. Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 396–405. [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck, P.C. Fermentative hydrogen production: Principles, progress, and prognosis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 7379–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, P.L.; Gibbs, M.D.; Morris, D.D.; Te'o, V.S.; Saul, D.J.; Moran, H.W. Molecular diversity of thermophilic cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999, 28, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Kataeva, I.; Westpheling, J.; Adams, M.W.W.; Kelly, R.M. Extremely thermophilic microorganisms for biomass conversion: Status and prospects. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanFossen, A.L.; Lewis, D.L.; Nichols, J.D.; Kelly, R.M. Polysaccharide degradation and synthesis by extremely thermophilic anaerobes. Incredible Anaerobes Physiol. Genomics Fuels 2008, 1125, 322–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kengen, S.W.M.; Goorissen, H.P.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; Stams, A.J.M.; van Niel, E.W.J.; Claassen, P.A.M. Biological hydrogen production by anaerobic microorganisms. In Biofuels; Soetaert, W., Verdamme, E.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 197–221. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaart, M.R.A.; Bielen, A.A.M.; van der Oost, J.; Stams, A.J.M.; Kengen, S.W.M. Hydrogen production by hyperthermophilic and extremely thermophilic bacteria and archaea: Mechanisms for reductant disposal. Environ. Technol. 2010, 31, 993–1003. [Google Scholar]

- De Vrije, T.; Claasen, P.A.M. Dark hydrogen fermentations. In Bio-methane & Bio-hydrogen; Reith, J.H., Wijffels, R.H., Barten, H., Eds.; Smiet Offset: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Willquist, K.; Zeidan, A.A.; van Niel, E.W. Physiological characteristics of the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus: An efficient hydrogen cell factory. Microb. Cell Fact. 2010, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, F.A.; Donnison, A.M.; Janssen, P.H.; Saul, D.; Rodrigo, A.; Bergquist, P.L.; Daniel, R.M.; Stackebrandt, E.; Morgan, H.W. Description of Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus gen. nov., sp. nov: An obligately anaerobic, extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994, 120, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissons, C.H.; Sharrock, K.R.; Daniel, R.M.; Morgan, H.W. Isolation of cellulolytic anaerobic extreme thermophiles from New Zealand thermal sites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 832–838. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P.H.S.; Sissons, C.H.; Daniel, R.M.; Morgan, H.W. Comparison of cellulolytic activities in Clostridium thermocellum and three thermophilic, cellulolytic anaerobes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1986, 51, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Donnison, A.M.; Brockelsby, C.M.; Morgan, H.W.; Daniel, R.M. The degradation of lignocellulosics by extremely thermophilic microorganisms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1989, 33, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredholt, S.; Sonne-Hansen, J.; Nielsen, P.; Mathrani, I.M.; Ahring, B.K. Caldicellulosiruptor kristjanssonii sp. nov., a cellulolytic extremely thermophilic, anaerobic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1999, 49, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P.P.; Gibbs, M.D.; Saul, D.J.; Bergquist, P.L. Cloning, sequencing and overexpression in Escherichia coli of a xylanase gene, xynA from the thermophilic bacterium Rt8.4 genus Caldicellulosiruptor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 45, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.D.; Reeves, R.A.; Farrington, G.K.; Anderson, P.; Williams, D.P.; Bergquist, P.L. Multidomain and multifunctional glycosyl hydrolases from the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor isolate Tok7B.1. Curr. Microbiol. 2000, 40, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-Brehm, S.D.; Mosher, J.J.; Vishnivetskaya, T.; Podar, M.; Carroll, S.; Allman, S.; Phelps, T.J.; Keller, M.; Elkins, J.G. Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis sp. nov., an anaerobic, extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic bacterium isolated from Obsidian pool, Yellowstone national park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.Y.; Patel, B.K.; Mah, R.A.; Baresi, L. Caldicellulosiruptor owensensis sp. nov., an anaerobic, extremely thermophilic, xylanolytic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, M.L.; Kublanov, I.V.; Kostrikina, N.A.; Tourova, T.P.; Kolganova, T.V.; Birkeland, N.K.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A. Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis sp. nov. and Caldicellulosiruptor hydrothermalis sp. nov., two extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic, anaerobic bacteria from Kamchatka thermal springs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 1492–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenovska, Z.; Mathrani, I.M.; Ahring, B.K. Isolation and characterization of Caldicellulosiruptor lactoaceticus sp. nov., an extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic, anaerobic bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 1995, 163, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.D.; Gibbs, M.D.; Ford, M.; Thomas, J.; Bergquist, P.L. Family 10 and 11 xylanase genes from Caldicellulosiruptor sp. strain Rt69B.1. Extremophiles 1999, 3, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Mathrani, I.M.; Ahring, B.K. Thermoanaerobium acetigenum spec. nov., a new anaerobic, extremely thermophilic, xylanolytic non-spore-forming bacterium isolated from an Icelandic hot spring. Arch. Microbiol. 1993, 159, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyenwoke, R.U.; Lee, Y.J.; Dabrowski, S.; Ahring, B.K.; Wiegel, J. Reclassification of “Thermoanaerobium acetigenum” as Caldicellulosiruptor acetigenus comb. nov and emendation of the genus description. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 1391–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlichnyi, V.A.; Svetlichnaya, T.P.; Chernykh, N.A.; Zavarzin, G.A. Anaerocellum thermophilum gen. nov. sp. nov.: An extremely thermophilic cellulolytic eubacterium isolated from hot-springs in the Valley of Geysers. Microbiology 1990, 59, 598–604. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.J.; Kataeva, I.; Wiegel, J.; Yin, Y.; Dam, P.; Xu, Y.; Westpheling, J.; Adams, M.W. Reclassification of “Anaerocellum thermophilum” as Caldicellulosiruptor bescii strain DSM 6725T sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 60, 2011–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Giannone, R.J.; Zurawski, J.V.; Ozdemir, I.; Ma, Q.; Yin, Y.B.; Xu, Y.; Kataeva, I.; Poole, F.L.; Adams, M.W.W.; et al. Caldicellulosiruptor core and pangenomes reveal determinants for noncellulosomal thermophilic deconstruction of plant biomass. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4015–4028. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Ozdemir, I.; Mistry, D.; Lucas, S.; Lapidus, A.; Cheng, J.F.; Goodwin, L.A.; Pitluck, S.; Land, M.L.; Hauser, L.J.; et al. Complete genome sequences for the anaerobic, extremely thermophilic plant biomass-degrading bacteria Caldicellulosiruptor hydrothermalis, Caldicellulosiruptor kristjanssonii, Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis, Caldicellulosiruptor owensensis, and Caldicellulosiruptor lactoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 1483–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, J.G.; Lochner, A.; Hamilton-Brehm, S.D.; Davenport, K.W.; Podar, M.; Brown, S.D.; Land, M.L.; Hauser, L.J.; Klingeman, D.M.; Raman, B.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the cellulolytic thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor obsidiansis OB47T. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 6099–6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataeva, I.A.; Yang, S.J.; Dam, P.; Poole, F.L.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, F.F.; Chou, W.C.; Xu, Y.; Goodwin, L.; Sims, D.R.; et al. Genome sequence of the anaerobic, thermophilic, and cellulolytic bacterium “Anaerocellum thermophilum” DSM 6725. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 3760–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Werken, H.J.G.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; VanFossen, A.L.; Willquist, K.; Lewis, D.L.; Nichols, J.D.; Goorissen, H.P.; Mongodin, E.F.; Nelson, K.E.; van Niel, E.W.J.; et al. Hydrogenomics of the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 6720–6729. [Google Scholar]

- Lamed, R.; Bayer, E.A. The cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 1988, 33, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Lewis, D.L.; Kelly, R.M. Phylogenetic, microbiological, and glycoside hydrolase diversities within the extremely thermophilic, plant biomass-degrading genus Caldicellulosirupt. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 8084–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanFossen, A.L.; Ozdemir, I.; Zelin, S.L.; Kelly, R.M. Glycoside hydrolase inventory drives plant polysaccharide deconstruction by the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, P.L.; Love, D.R.; Croft, J.E.; Streiff, M.B.; Daniel, R.M.; Morgan, W.H. Genetics and potential biotechnological applications of thermophilic and extremely thermophilic microorganisms. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 1987, 5, 199–244. [Google Scholar]

- Love, D.R.; Streiff, M.B. Molecular cloning of a beta-glucosidase gene from an extremely thermophilic anaerobe in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. BioTechnology 1987, 5, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.C.; Schofield, L.R.; Coolbear, T.; Daniel, R.M.; Morgan, H.W. Purification and properties of an aryl beta-xylosidase from a cellulolytic extreme thermophile expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 1991, 273, 645–650. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, L.R.; Daniel, R.M. Purification and properties of a beta-1,4-xylanase from a cellulolytic extreme thermophile expressed in Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biochem. 1993, 25, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, G.D.; McHale, R.H.; Gibbs, M.D.; Bergquist, P.L. Cloning and sequence of a type I pullulanase from an extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Gene Structure and Expression 1997, 1354, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthi, E.; Jasmat, N.B.; Bergquist, P.L. Xylanase from the extremely thermophilic bacterium “Caldocellum saccharolyticum”: Overexpression of the gene in Escherichia coli and characterization of the gene product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 2677–2683. [Google Scholar]

- Luthi, E.; Bergquist, P.L. A beta-D-xylosidase from the thermophile “Caldocellum saccharolyticum” expressed in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990, 67, 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Luthi, E.; Jasmat, N.B.; Bergquist, P.L. Overproduction of an acetylxylan esterase from the extreme thermophile “Caldocellum saccharolyticum” in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1990, 34, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te'o, V.S.J.; Saul, D.J.; Bergquist, P.L. Cela, another gene coding for a multidomain cellulase from the extreme thermophile “Caldocellum saccharolyticum”. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1995, 43, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.S.; Kim, J.E.; Choi, J.G.; Oh, D.K. Characterization of a recombinant cellobiose 2-epimerase from Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and its application in the production of mannose from glucose. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, D.J.; Williams, L.C.; Grayling, R.A.; Chamley, L.W.; Love, D.R.; Bergquist, P.L. Celb, a gene coding for a bifunctional cellulase from the extreme thermophile “Caldocellum saccharolyticum”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 3117–3124. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, D.D.; Reeves, R.A.; Gibbs, M.D.; Saul, D.J.; Bergquist, P.L. Correction of the beta-mannanase domain of the Celc pseudogene from Caldocellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and activity of the gene product on Kraft pulp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 2262–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Luthi, E.; Jasmat, N.B.; Grayling, R.A.; Love, D.R.; Bergquist, P.L. Cloning, sequence analysis, and expression in Escherichia coli of a gene coding for a beta-mannanase from the extremely thermophilic bacterium “Caldocellum saccharolyticum”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 694–700. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, G.; Lewis, D.; Notey, J.; Kelly, R.; Muddiman, D. Part I: Characterization of the extracellular proteome of the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus by GeLC-MS2 (vol 398, pg 377, 2010). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 1837–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, I.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Kelly, R.M. S-Layer homology domain proteins Csac_0678 and Csac_2722 are implicated in plant polysaccharide deconstruction by the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, G.; Rakhely, G.; Kovacs, K.L. Hydrogen production from biopolymers by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and stabilization of the system by immobilization. Int.l J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 6953–6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanFossen, A.L.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; Kengen, S.M.W.; Kelly, R.M. Carbohydrate utilization patterns for the extremely thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus reveal broad growth substrate preferences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7718–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrije, T.; Bakker, R.R.; Budde, M.A.; Lai, M.H.; Mars, A.E.; Claassen, P.A. Efficient hydrogen production from the lignocellulosic energy crop Miscanthus by the extreme thermophilic bacteria Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and Thermotoga neapolitana. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2009, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrije, T.; Budde, M.A.W.; Lips, S.J.; Bakker, R.R.; Mars, A.E.; Claassen, P.A.M. Hydrogen production from carrot pulp by the extreme thermophiles Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and Thermotoga neapolitana. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 13206–13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrije, T.; Mars, A.E.; Budde, M.A.W.; Lai, M.H.; Dijkema, C.; de Waard, P.; Claassen, P.A.M. Glycolytic pathway and hydrogen yield studies of the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willquist, K.; van Niel, E.W.J. Lactate formation in Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus is regulated by the energy carriers pyrophosphate and ATP. Metab. Eng. 2010, 12, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Guss, A.M.; Karpinets, T.V.; Parks, J.M.; Smolin, N.; Yang, S.H.; Land, M.L.; Klingeman, D.M.; Bhandiwad, A.; Rodriguez, M.; et al. Mutant alcohol dehydrogenase leads to improved ethanol tolerance in Clostridium thermocellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13752–13757. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Wu, G.G.; Shao, W.L. The aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase (AdhE) in relation to the ethanol formation in Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus JW200. Anaerobe 2008, 14, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielen, A.A.M.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; VanFossen, A.L.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Stams, A.J.M.; van der Oost, J.; Kelly, R.M.; Kengen, S.M.W. A thermophile under pressure:Transcriptional analysis of the response of Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus to different H2 partial pressures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Hutchins, A.; Sung, S.J.S.; Adams, M.W.W. Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus, functions as a CoA-dependent pyruvate decarboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 9608–9613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, V.; Mutharasan, R. Ethanol fermentation characteristics of Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus. Enzyme. Microb. Technol. 1985, 7, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.G.; Guerinot, M.L.; Lynd, L.R. Cloning of L-lactate dehydrogenase and elimination of lactic acid production via gene knockout in Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum JW/SL-YS485. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 65, 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- Soboh, B.; Linder, D.; Hedderich, R. A multisubunit membrane-bound [NiFe] hydrogenase and an NADH-dependent Fe-only hydrogenase in the fermenting bacterium Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Microbiology 2004, 150, 2451–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.S.; Adams, M.W.W. An unusual oxygen-sensitive, iron- and zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaart, M.R.A. Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010; Unpublished work.

- DeLacey, A.L.; Stadler, C.; Fernandez, V.M.; Hatchikian, E.C.; Fan, H.J.; Li, S.H.; Hall, M.B. IR spectroelectrochemical study of the binding of carbon monoxide to the active site of Desulfovibrio fructosovorans Ni-Fe hydrogenase. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 7, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, B.J.; Peters, J.W. Binding of exogenously added carbon monoxide at the active site of the iron-only hydrogenase (CpI) from Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 12969–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, J.K. Biological production of PPi. In Biological Role of Inorganic Pyrophosphate; Heinonen, J.K., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, London, UK, 2001; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Brevet, A.; Fromant, M.; Leveque, F.; Schmitter, J.M.; Blanquet, S.; Plateau, P. Pyrophosphatase is essential for growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 5686–5689. [Google Scholar]

- Bielen, A.A.M.; Willquist, K.; Engman, J.; van der Oost, J.; van Niel, E.W.J.; Kengen, S.W.M. Pyrophosphate as a central energy carrier in the hydrogen-producing extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 307, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E. Pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructokinase, an anaerobic glycolytic enzyme? FEBS Lett. 1991, 285, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, E.W.J.; Claassen, P.A.M.; Stams, A.J.M. Substrate and product inhibition of hydrogen production by the extreme thermophile, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 81, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren, M.; Willquist, K.; Zacchi, G.; van Niel, E.W.J. A kinetic model for quantitative evaluation of the effect of hydrogen and osmolarity on hydrogen production by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willquist, K.; Pawar, S.S.; van Niel, E.W.J. Reassessment of hydrogen tolerance in Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, J.T.; Bagley, D.M. Supersaturation of dissolved H2 and CO2 during fermentative hydrogen production with N2 sparging. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006, 28, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielen, A.A.M. Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; Unpublished work.

- Kadar, Z.; de Vrijek, T.; van Noorden, G.E.; Budde, M.A.W.; Szengyel, Z.; Reczey, K.; Claassen, P.A.M. Yields from glucose, xylose, and paper sludge hydrolysate during hydrogen production by the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2004, 113–116, 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Willquist, K.; Claassen, P.A.M.; van Niel, E.W.J. Evaluation of the influence of CO2 on hydrogen production by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 4718–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, J.P.; Plyasunov, A.V. Carbohydrates in thermophile metabolism: Calculation of the standard molal thermodynamic properties of aqueous pentoses and hexoses at elevated temperatures and pressures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2001, 65, 3901–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amend, J.P.; Shock, E.L. Energetics of overall metabolic reactions of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic Archaea and Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 25, 175–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, K. Enthalpy change for reduction of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide. Biochem. J. 1974, 143, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Thauer, R.K.; Jungermann, K.; Decker, K. Energy-conservation in chemotropic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 1977, 41, 100–180. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, G.D.; Burns, A. Thermochemical characterization of sodium dithionite, flavin mononucleotide, flavin-adenine dinucleotide and methyl and benzyl viologens as low-potential reductants for biological-systems. Biochem. J. 1975, 152, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel, E.; Schmidt, S.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Muller, V. Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 613–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schut, G.J.; Adams, M.W.W. The iron-hydrogenase of Thermotoga maritima utilizes ferredoxin and NADH synergistically: A new perspective on anaerobic hydrogen production. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4451–4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.A.; Bakker, R.R.; de Vrije, T.; Claassen, P.A.M.; Koukios, E.G. Integration of first and second generation biofuels: Fermentative hydrogen production from wheat grain and straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 128, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.A.; Bakker, R.R.; de Vrije, T.; Claassen, P.A.M.; Koukios, E.G. Dilute-acid pretreatment of barley straw for biological hydrogen production using Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.; Barker, R.; de Vrije, T.; Niel, E.V.; Koukios, E.; Claassen, P. Exploring critical factors for fermentative hydrogen production from various types of lignocellulosic biomass. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2011, 90, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, E.; Mars, A.E.; Peksel, B.; Louwerse, A.; Yücel, M.; Gündüz, U.; Claassen, P.A.M.; Eroğlu, I. Biohydrogen production from beet molasses by sequential dark and photofermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, A.E.; Veuskens, T.; Budde, M.A.W.; van Doeveren, P.; Lips, S.J.; Bakker, R.R.; de Vrije, T.; Claassen, P.A.M. Biohydrogen production from untreated and hydrolyzed potato steam peels by the extreme thermophiles Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and Thermotoga neapolitana. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 7730–7737. [Google Scholar]

- Herbel, Z.; Rakhely, G.; Bagi, Z.; Ivanova, G.; Acs, N.; Kovacs, E.; Kovacs, K.L. Exploitation of the extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus in hydrogen and biogas production from biomasses. Environ. Technol. 2010, 31, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, J.A.; Bakker, R.R.; de Vrije, T.; Urbaniec, K.; Koukios, E.G.; Claassen, P.A.M. Prospects of utilization of sugar beet carbohydrates for biological hydrogen production in the EU. J. Cleaner Prod. 2010, 18, S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.A.; Bakker, R.R.; de Vrije, T.; Koukios, E.G.; Claassen, P.A.M. Pretreatment of sweet sorghum bagasse for hydrogen production by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 7738–7747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.J.; Kataeva, I.; Hamilton-Brehm, S.D.; Engle, N.L.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Doeppke, C.; Davis, M.; Westpheling, J.; Adams, M.W.W. Efficient degradation of lignocellulosic plant biomass, without pretreatment, by the thermophilic anaerobe “Anaerocellum thermophilum” DSM 6725. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4762–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.A.; Bakker, R.R.; Budde, M.A.W.; de Vrije, T.; Claassen, P.A.M.; Koukios, E.G. Fermentative hydrogen production from pretreated biomass: A comparative study. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 6331–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, G.; Rakhely, G.; Kovacs, K.L. Thermophilic biohydrogen production from energy plants by Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and comparison with related studies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 3659–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagi, Z.; Acs, N.; Balint, B.; Horvath, L.; Dobo, K.; Perei, K.R.; Rakhely, G.; Kovacs, K.L. Biotechnological intensification of biogas production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadar, Z.; de Vrije, T.; Budde, M.A.; Szengyel, Z.; Reczey, K.; Claassen, P.A. Hydrogen production from paper sludge hydrolysate. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2003, 105–108, 557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Willquist, K.; van Niel, E.W.J. Growth and hydrogen production characteristics of Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus on chemically defined minimal media. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 4925–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddiman, D.; Andrews, G.; Lewis, D.; Notey, J.; Kelly, R. Part II: Defining and quantifying individual and co-cultured intracellular proteomes of two thermophilic microorganisms by GeLC-MS(2) and spectral counting. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Groenestijn, J.W.; Geelhoed, J.S.; Goorissen, H.P.; Meesters, K.P.; Stams, A.J.; Claassen, P.A. Performance and population analysis of a non-sterile trickle bed reactor inoculated with Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus, a thermophilic hydrogen producer. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 102, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, E.W.J.; Budde, M.A.W.; de Haas, G.G.; van der Wal, F.J.; Claasen, P.A.M.; Stams, A.J.M. Distinctive properties of high hydrogen producing extreme thermophiles, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus and Thermotoga elfii. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren, M.; Wallberg, O.; Zacchi, G. Techno-economic comparison of a biological hydrogen process and a 2nd generation ethanol process using barley straw as feedstock. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9524–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren, M.; Zacchi, G. Techno-economic evaluation of a two-step biological process for hydrogen production. Biotechnol. Prog. 2010, 26, 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, K.; Das, D. Improvement of fermentative hydrogen production: Various approaches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 65, 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Han, S.K.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, H.S. Effect of gas sparging on continuous fermentative hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 2158–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, J.T.; Bagley, D.M. Optimisation and design of nitrogen-sparged fermentative hydrogen production bioreactors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 6558–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.C.; Zhang, R.H.H.; Upadhyaya, S.K. The effect of low pressure and mixing on biological hydrogen production via anaerobic fermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 11504–11513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamed, R.J.; Lobos, J.H.; Su, T.M. Effects of stirring and hydrogen on fermentation products of Clostridium thermocellum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 1216–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Junghare, M.; Subudhi, S.; Lal, B. Improvement of hydrogen production under decreased partial pressure by newly isolated alkaline tolerant anaerobe, Clostridium butyricum TM-9A: Optimization of process parameters. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 3160–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, B.; Nath, K.; Das, D. Improvement of biohydrogen production under decreased partial pressure of H2 by Enterobacter cloacae. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006, 28, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnleitner, A.; Peintner, C.; Wukovits, W.; Friedl, A.; Schnitzhofer, W. Process investigations of extreme thermophilic fermentations for hydrogen production: Effect of bubble induction and reduced pressure. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Hartmeier, W.; Chang, J.S. Enhancing hydrogen production of Clostridium butyricum using a column reactor with square-structured ceramic fittings. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 6549–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.A.; van Niel, E.W.J. Developing a thermophilic hydrogen-producing co-culture for efficient utilization of mixed sugars. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 4524–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, A.A.; van Niel, E.W.J. A quantitative analysis of hydrogen production efficiency of the extreme thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor owensensis OL(T). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, P.A.M.; de Vrije, T. Non-thermal production of pure hydrogen from biomass: HYVOLUTION. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Grot, S.; Logan, B.E. Electrochemically assisted microbial production of hydrogen from acetate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 4317–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, E.; Uyar, B.; Özgür, E.; Yücel, M.; Eroğlu, I.; Gündüz, U. Photofermentative hydrogen production using dark fermentation effluent of sugar beet thick juice in outdoor conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, E.; Afsar, N.; de Vrije, T.; Yücel, M.; Gündüz, U.; Claassen, P.A.M.; Eroğlu, I. Potential use of thermophilic dark fermentation effluents in photofermentative hydrogen production by Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Cleaner Prod. 2010, 18, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.; Farkas, J.; Huddleston, J.R.; Olivar, E.; Westpheling, J. Methylation by a unique α-class N4-Cytosine methyltransferase is required for DNA transformation of Caldicellulosiruptor bescii DSM6725. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43844. [Google Scholar]

- Bielen, A.A.M. Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; Unpublished work.

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bielen, A.A.M.; Verhaart, M.R.A.; Van der Oost, J.; Kengen, S.W.M. Biohydrogen Production by the Thermophilic Bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus: Current Status and Perspectives. Life 2013, 3, 52-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/life3010052

Bielen AAM, Verhaart MRA, Van der Oost J, Kengen SWM. Biohydrogen Production by the Thermophilic Bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus: Current Status and Perspectives. Life. 2013; 3(1):52-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/life3010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleBielen, Abraham A. M., Marcel R. A. Verhaart, John Van der Oost, and Servé W. M. Kengen. 2013. "Biohydrogen Production by the Thermophilic Bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus: Current Status and Perspectives" Life 3, no. 1: 52-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/life3010052