Predicting Outcome after Percutaneous Ablation for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Various Imaging Modalities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Ultrasonography

- -

- Definity®/Luminity® (Lantheus Medical Imaging Inc., North Billerica, MA, USA);

- -

- SonoVue®/Lumason® (Bracco Suisse SA, Geneva, Switzerland);

- -

- Optison® (GE Healthcare AS, Oslo, Norway);

- -

- Sonazoid® (GE Healthcare AS, Oslo, Norway).

2.1. Gross Classification

- -

- The small nodular type with indistinct margin.

- -

- The simple nodular (SN) type, with a clear round shape.

- -

- The simple nodular with extranodular growth (SNEG) type, with a clear round shape and one or more tumor growths coexisting around the nodules.

- -

- The confluent multinodular (CMN) type, consists of clusters of small nodules.

- -

- The infiltrative type.

2.2. Intratumoral Blood Flow

2.3. Computer-Assisted Color Parameter Imaging

2.4. Combination of Percutaneous Ablation with CEUS

3. Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography

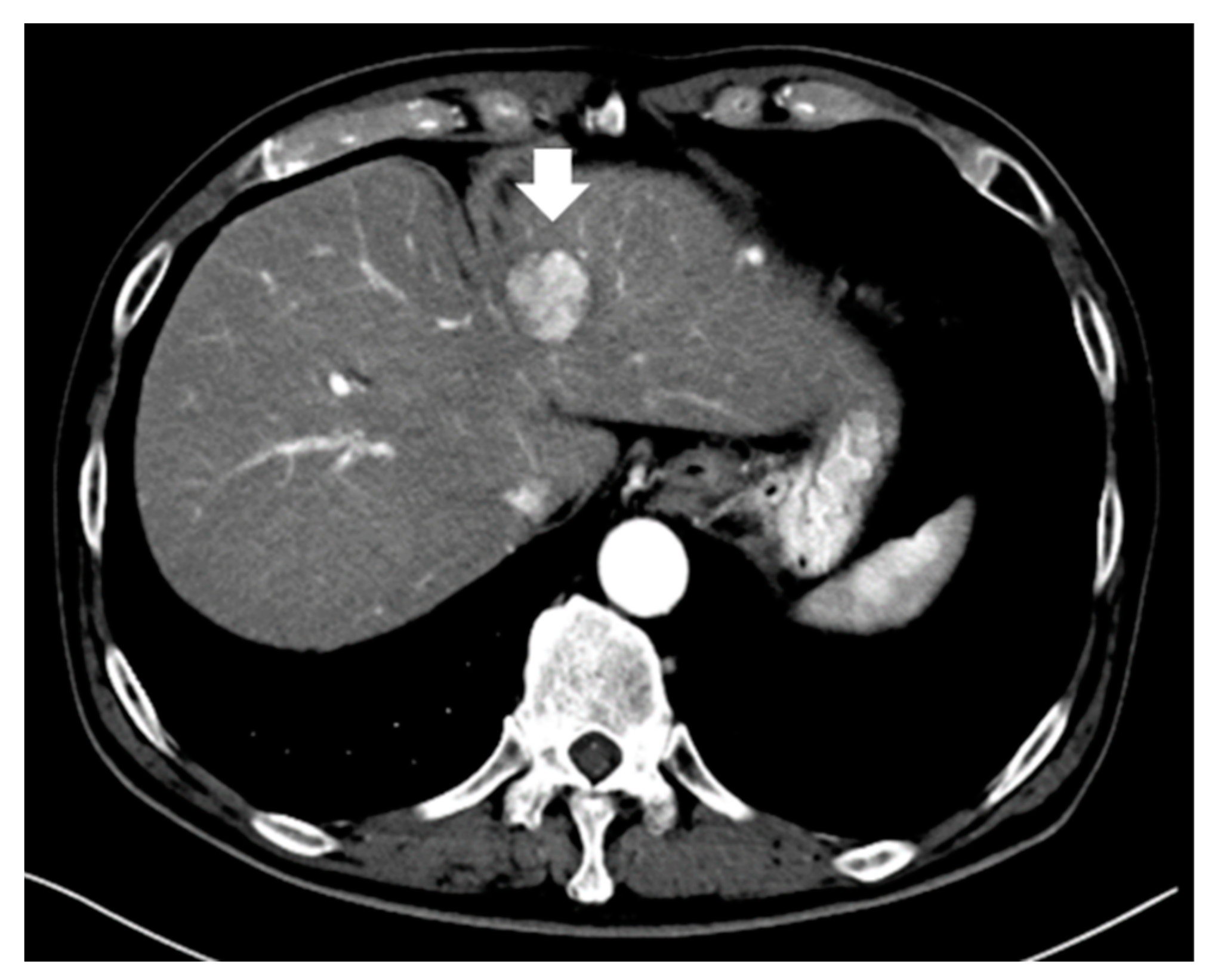

3.1. Enhancement Pattern in the Arterial Phase

3.2. Intratumoral Arteries and Enhancement Pattern

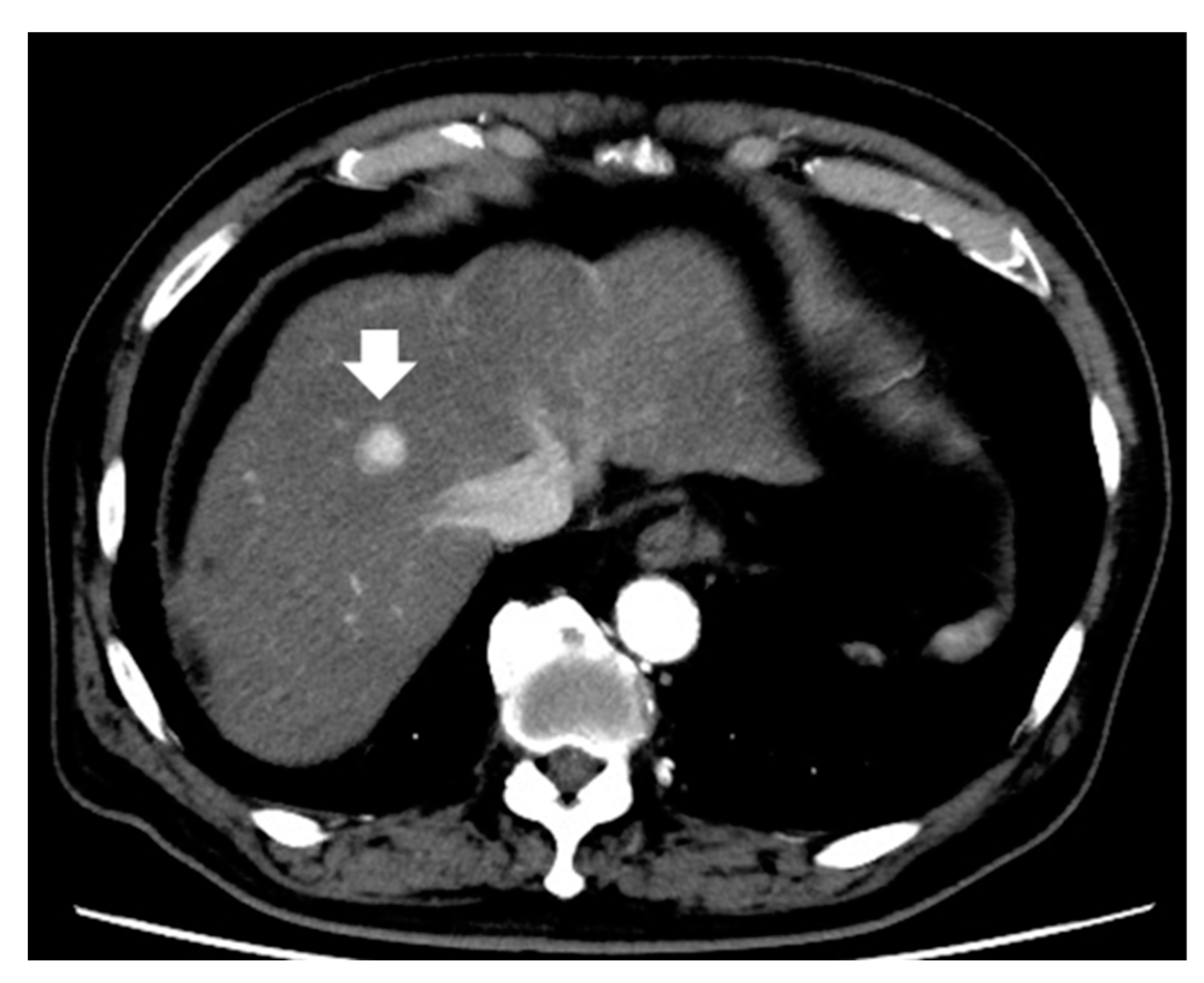

4. Magnetic Resonance Imaging

4.1. Enhancement Pattern in the Hepatobiliary Phase

4.2. Enhancement Pattern in the Arterial Phase

4.3. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging

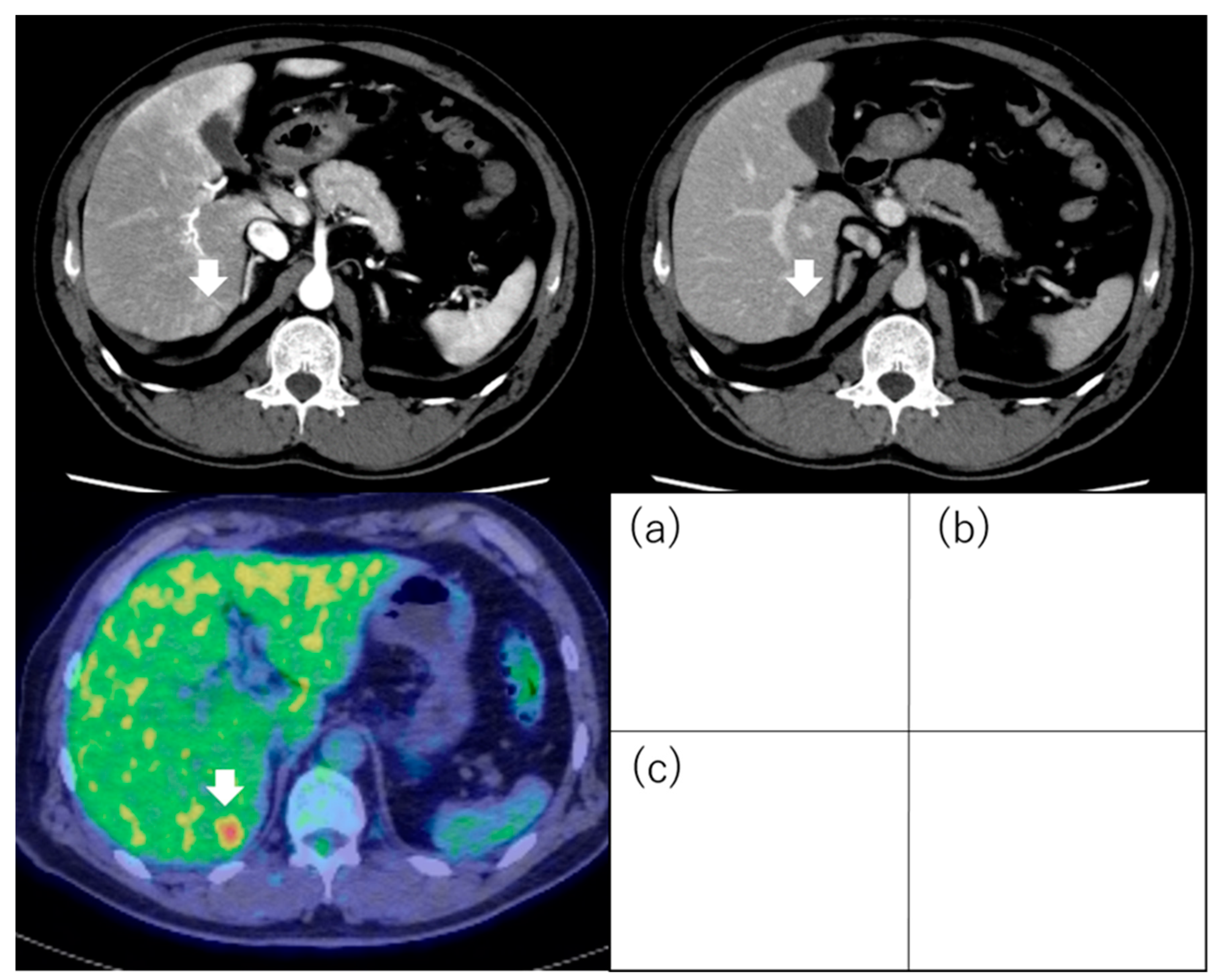

5. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography

5.1. Standardized Uptake Value

5.2. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Uptake

6. Limitation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasegawa, K.; Takemura, N.; Yamashita, T.; Watadani, T.; Kaibori, M.; Kubo, S.; Shimada, M.; Nagano, H.; Hatano, E.; Aikata, H.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Japan Society of Hepatology 2021 version (5th JSH-HCC Guidelines). Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. 2023, 53, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. AASLD practice guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 9900, 10–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Beppu, T.; Ishiko, T.; Horino, K.; Baba, Y.; Mizumoto, T.; Hayashi, H.; Okabe, H.; Horlad, H.; Doi, K.; et al. Intrahepatic dissemination of hepatocellular carcinoma after local ablation therapy. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2008, 15, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Tamai, H.; Shingaki, N.; Moribata, K.; Shiraki, T.; Deguchi, H.; Ueda, K.; Enomoto, S.; Magari, H.; Inoue, I.; et al. Diffuse intrahepatic recurrence after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for solitary and small hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2009, 3, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoli, N.; Casaril, A.; Hilal, M.d.A.; Mangiante, G.; Marchiori, L.; Ciola, M.; Invernizzi, L.; Campagnaro, T.; Mansueto, G. A case of rapid intrahepatic dissemination of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency thermal ablation. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 188, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolani, N.; Tiberio, G.A.; Ronconi, M.; Coniglio, A.; Ghidoni, S.; Gaverini, G.; Giulini, S.M. Aggressive recurrence after radiofrequency ablation of liver neoplasms. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2003, 50, 2179–2184. [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzenente, A.; Manzoni, G.D.; Molfetta, M.; Pachera, S.; Genco, B.; Donataccio, M.; Guglielmi, A. Rapid progression of hepatocellular carcinoma after Radiofrequency Ablation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, T.; Tamai, T.; Ikeda, K.; Imamura, M.; Nishimura, A.; Yamashiki, N.; Nakagawa, T.; Inoue, K. Rapid progression of hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in the primary tumour region. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001, 13, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, Y.; Kurata, M.; Ohkohchi, N. Rapid and aggressive recurrence accompanied by portal tumor thrombus after radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 8, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lim, H.K.; Choi, D.; Lee, W.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, C.K.; Jeon, Y.H.; Lee, J.M.; Rhim, H. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: Effect of histologic grade on therapeutic results. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006, 186, S327–S333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, J.; Tateishi, R.; Shiina, S.; Goto, E.; Sato, T.; Ohki, T.; Masuzaki, R.; Goto, T.; Yoshida, H.; Kanai, F.; et al. Neoplastic seeding after radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 3057–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.C.; Cheng, J.S.; Lai, K.H.; Lin, C.P.; Lo, G.H.; Lin, C.K.; Hsu, P.I.; Chan, H.H.; Lo, C.C.; Tsai, W.L.; et al. Factors for early tumor recurrence of single small hepatocellular carcinoma after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, S.; Itamoto, T.; Nakahara, H.; Kohashi, T.; Ohdan, H.; Hino, H.; Ochi, M.; Tashiro, H.; Asahara, T. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic factors of resected solitary small-sized hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2005, 52, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, K.; Beppu, T.; Nakayama, Y.; Ishiko, T.; Horino, K.; Komori, H.; Masuda, T.; Hayashi, H.; Okabe, H.; Baba, Y.; et al. Preoperative prediction of poorly differentiated components in small-sized hepatocellular carcinoma for safe local ablation therapy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 100, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okusaka, T.; Okada, S.; Ueno, H.; Ikeda, M.; Shimada, K.; Yamamoto, J.; Kosuge, T.; Yamasaki, S.; Fukushima, N.; Sakamoto, M. Satellite lesions in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma with reference to clinicopathologic features. Cancer 2002, 95, 1931–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Tsuijita, E.; Takeishi, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Kira, S.; Mori, M.; Aishima, S.; Taketomi, A.; Shirabe, K.; Ishida, T.; et al. Predictors for microinvasion of small hepatocellular carcinoma </= 2 cm. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.-W.; Shim, J.H.; Yoon, J.-H.; Kim, C.Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Kim, Y.T.; Kim, Y.J. Treatment and clinical outcome of needle-track seeding from hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2011, 17, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.; Hegab, B.; Hyde, C.; Guo, B.; Buckels, J.A.; Mirza, D.F. Needle track seeding following biopsy of liver lesions in the diagnosis of hepatocellular cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2008, 57, 1592–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpakowski, J.L.; Drasin, T.E.; Lyon, L.L. Rate of seeding with biopsies and ablations of hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. Hepatol. Commun. 2017, 1, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso, L.; Spadaccini, M.; Donadon, M.; Personeni, N.; Elamin, A.; Aghemo, A.; Lleo, A. Role of liver biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 6041–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Barr, R.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Burns, P.N.; Cantisani, V.; Chammas, M.C.; Chaubal, N.; Choi, B.I.; Clevert, D.A.; et al. Guidelines and Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Liver-Update 2020 WFUMB in Cooperation with EFSUMB, AFSUMB, AIUM, and FLAUS. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 2579–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa, K.; Moriyasu, F.; Miyahara, T.; Yuki, M.; Iijima, H. Phagocytosis of ultrasound contrast agent microbubbles by Kupffer cells. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2007, 33, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Tateishi, R.; Kariyama, K.; Shiina, S.; Toyoda, H.; Imai, Y.; Hiraoka, A.; Ikeda, M.; et al. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Japan: JSH Consensus Statements and Recommendations 2021 Update. Liver Cancer 2021, 10, 181–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, A.-M.; Takayama, T.; Sano, K.; Kubota, K.; Akahane, M.; Ohtomo, K.; Makuuchi, M. Predictive value of gross classification of hepatocellular carcinoma on recurrence and survival after hepatectomy. J. Hepatol. 2000, 33, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, M.; Rikimaru, T.; Hamatsu, T.; Yamashita, Y.-i.; Terashi, T.; Taguchi, K.-i.; Tanaka, S.; Shirabe, K.; Sugimachi, K. The role of macroscopic classification in nodular-type hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2001, 182, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumie, S.; Kuromatsu, R.; Okuda, K.; Ando, E.; Takata, A.; Fukushima, N.; Watanabe, Y.; Kojiro, M.; Sata, M. Microvascular Invasion in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Its Predictable Clinicopathological Factors. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, K.; Chung, H.; Kudo, M.; Haji, S.; Minami, Y.; Maekawa, K.; Hayaishi, S.; Nagai, T.; Takita, M.; Kudo, K.; et al. Usefulness of the post-vascular phase of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with sonazoid in the evaluation of gross types of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2010, 78 (Suppl. S1), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, X.; Li, L.; Su, C.; Sun, J.; Zhan, C.; Feng, D.; Cheng, W. Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography with Sonazoid for Diagnosis of Microvascular Invasion in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 48, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuta, J.; Shingaki, N.; Ida, Y.; Shimizu, R.; Hayami, S.; Ueno, M.; Fukatsu, K.; Itonaga, M.; Yoshida, T.; Maeda, Y.; et al. Irregular Defects in Hepatocellular Carcinomas During the Kupffer Phase of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography with Perfluorobutane Microbubbles: Pathological Features and Metastatic Recurrence After Surgical Resection. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitao, A.; Zen, Y.; Matsui, O.; Gabata, T.; Nakanuma, Y. Hepatocarcinogenesis: Multistep changes of drainage vessels at CT during arterial portography and hepatic arteriography--radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology 2009, 252, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, H.; Takahashi, M.; Shimada, T.; Sekimoto, T.; Kamesaki, H.; Kanai, F.; Yokosuka, O. Pretreatment microbubble-induced enhancement in hepatocellular carcinoma predicts intrahepatic distant recurrence after radiofrequency ablation. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 200, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Dong, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, B.; Tian, Y.; Tan, H.; Cheng, W. Quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound to predict intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation: A cohort study. Int. J. Hyperth. 2020, 37, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Qin, X.-C.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.-Z.; Zhou, X. Efficacy of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Washout Rate in Predicting Hepatocellular Carcinoma Differentiation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2015, 41, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Li, K.; Yang, H.; Lu, S.; Ding, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Wu, W.; Jing, X.; et al. Analysis of Sonazoid contrast-enhanced ultrasound for predicting the risk of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective multicenter study. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 7066–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Fan, Z.H.; Yin, S.S.; Yan, K.; Sun, L.Q.; Jiang, B.B. Diagnostic value of color parametric imaging and contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the differentiation of hepatocellular adenoma and well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Ultrasound JCU 2022, 50, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, G.; Cao, K.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Z.N.; Bai, X.M.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; et al. Computer-Aided Color Parameter Imaging of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Evaluates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Hemodynamic Features and Predicts Radiofrequency Ablation Outcome. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 48, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, M.; Tan, Y.; Zhuang, B.; Lin, M.; Kuang, M.; Xie, X. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound-guided feeding artery ablation as add-on to percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma with a modified ablative technique and tumor perfusion evaluation. Int. J. Hyperth. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Hyperthermic Oncol. N. Am. Hyperth. Group 2020, 37, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Hirakawa, M.; Yatsuji, H.; Sezaki, H.; Hosaka, T.; Akuta, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Saitoh, S.; Suzuki, F.; et al. New classification of dynamic computed tomography images predictive of malignant characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. 2010, 40, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Seko, Y.; Hosaka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Saitoh, S.; Kumada, H. Heterogeneous type 4 enhancement of hepatocellular carcinoma on dynamic CT is associated with tumor recurrence after radiofrequency ablation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, W665–W673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakachi, K.; Tamai, H.; Mori, Y.; Shingaki, N.; Moribata, K.; Deguchi, H.; Ueda, K.; Inoue, I.; Maekita, T.; Iguchi, M.; et al. Prediction of poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma using contrast computed tomography. Cancer Imaging Off. Publ. Int. Cancer Imaging Soc. 2014, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, R.; Tamai, H.; Mori, Y.; Shingaki, N.; Maeshima, S.; Nuta, J.; Maeda, Y.; Moribata, K.; Muraki, Y.; Deguchi, H.; et al. The arterial tumor enhancement pattern on contrast-enhanced computed tomography is associated with primary cancer death after radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2016, 10, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Hua, Y.; Dai, T.; He, J.; Tang, M.; Fu, X.; Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Qiu, Y. Development and validation of a novel predictive scoring model for microvascular invasion in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 88, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Xie, C.; Qin, S.; Yan, M.; Ke, Q.; Jin, X.; Lin, T.; Zhou, M.; et al. Two-Trait Predictor of Venous Invasion on Contrast-Enhanced CT as a Preoperative Predictor of Outcomes for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Hepatectomy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 688087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzulli, M.; Brocchi, S.; Cucchetti, A.; Mazzotti, F.; Mosconi, C.; Sportoletti, C.; Brandi, G.; Pinna, A.D.; Golfieri, R. Can Current Preoperative Imaging Be Used to Detect Microvascular Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma? Radiology 2016, 279, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Y.; Yang, K. Gadoxetic acid disodium (Gd-EOBDTPA)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2014, 39, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motosugi, U.; Murakami, T.; Lee, J.M.; Fowler, K.J.; Heiken, J.P.; Sirlin, C.B. Recommendation for terminology: Nodules without arterial phase hyperenhancement and with hepatobiliary phase hypointensity in chronic liver disease. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2018, 48, 1169–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motosugi, U.; Bannas, P.; Sano, K.; Reeder, S.B. Hepatobiliary MR contrast agents in hypovascular hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 41, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Nouso, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shiraha, H.; Ohnishi, H.; Toshimori, J.; Kuwaki, K.; Hagihara, H.; Takayama, H.; Yamamoto, K. The diagnosis of hypovascular hepatic lesions showing hypo-intensity in the hepatobiliary phase of Gd-EOB- DTPA-enhanced MR imaging in high-risk patients for hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Med. Okayama 2013, 67, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Woo, S.; Han, S.; Suh, C.H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.M. Hepatobiliary phase hypointense nodule without arterial phase hyperenhancement: Are they at risk of HCC recurrence after ablation or surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 1624–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Choi, B.I.; Lee, E.S.; Park, S.B.; Lee, J.B. How to Differentiate Borderline Hepatic Nodules in Hepatocarcinogenesis: Emphasis on Imaging Diagnosis. Liver Cancer 2017, 6, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, T.; Makuuchi, M.; Hirohashi, S.; Sakamoto, M.; Okazaki, N.; Takayasu, K.; Kosuge, T.; Motoo, Y.; Yamazaki, S.; Hasegawa, H. Malignant transformation of adenomatous hyperplasia to hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 1990, 336, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yu, S.J.; Han, J.K.; et al. Non-hypervascular hepatobiliary phase hypointense nodules on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI: Risk of HCC recurrence after radiofrequency ablation. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, T.; Imai, Y.; Igura, T.; Kogita, S.; Sawai, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nakahara, M.; Morimoto, O.; et al. Non-Hypervascular Hypointense Hepatic Nodules during the Hepatobiliary Phase of Gadolinium-Ethoxybenzyl-Diethylenetriamine Pentaacetic Acid-Enhanced MRI as a Risk Factor of Intrahepatic Distant Recurrence after Radiofrequency Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig. Dis. 2017, 35, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyoda, H.; Kumada, T.; Tada, T.; Niinomi, T.; Ito, T.; Sone, Y.; Kaneoka, Y.; Maeda, A. Non-hypervascular hypointense nodules detected by Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI are a risk factor for recurrence of HCC after hepatectomy. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, H.; Kumada, T.; Tada, T.; Sone, Y.; Maeda, A.; Kaneoka, Y. Non-hypervascular hypointense nodules on Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI as a predictor of outcomes for early-stage HCC. Hepatol. Int. 2015, 9, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, J.K. Hepatobiliary phase of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI in patients with HCC: Prognostic features before resection, ablation, or TACE. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 3627–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Xiao, H.; Xie, Z.L.; Shen, J.X.; Chen, Z.B.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, B.; Peng, Z.W.; Kuang, M.; Lai, J.M.; et al. The presence of microvascular invasion guides treatment strategy in recurrent HBV-related HCC. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 3473–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.E.; Sinn, D.H.; Park, C.K. Preoperative gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI for predicting microvascular invasion in patients with single hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kang, T.W.; Song, K.D.; Lee, M.W.; Rhim, H.; Lim, H.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Sinn, D.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, K.; et al. Effect of Microvascular Invasion Risk on Early Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Surgery and Radiofrequency Ablation. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yu, N.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Yan, J.; Zhang, G. Pre-radiofrequency ablation MRI imaging features predict the local tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine 2020, 99, e23924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Kim, D.W.; Park, Y.N.; Chung, Y.E.; Rhee, H.; Kim, M.J. Single Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Preoperative MR Imaging to Predict Early Recurrence after Curative Resection. Radiology 2015, 276, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.; Cristescu, M.; Lee, M.H.; Moreland, A.; Hinshaw, J.L.; Lee, F.T.; Brace, C.L. Effects of Microwave Ablation on Arterial and Venous Vasculature after Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Radiology 2016, 281, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierans, A.S.; Leonardou, P.; Hayashi, P.; Brubaker, L.M.; Elazzazi, M.; Shaikh, F.; Semelka, R.C. MRI findings of rapidly progressive hepatocellular carcinoma. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2010, 28, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.; An, C.; Kim, H.Y.; Yoo, J.E.; Park, Y.N.; Kim, M.J. Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Irregular Rim-Like Arterial Phase Hyperenhancement: More Aggressive Pathologic Features. Liver Cancer 2019, 8, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petukhova-Greenstein, A.; Zeevi, T.; Yang, J.; Chai, N.; DiDomenico, P.; Deng, Y.; Ciarleglio, M.; Haider, S.P.; Onyiuke, I.; Malpani, R.; et al. MR Imaging Biomarkers for the Prediction of Outcome after Radiofrequency Ablation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Qualitative and Quantitative Assessments of the Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System and Radiomic Features. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. JVIR 2022, 33, 814–824.e813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazioli, L.; Olivetti, L.; Fugazzola, C.; Benetti, A.; Stanga, C.; Dettori, E.; Gallo, C.; Matricardi, L.; Giacobbe, A.; Chiesa, A. The pseudocapsule in hepatocellular carcinoma: Correlation between dynamic MR imaging and pathology. Eur. Radiol. 1999, 9, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Tamai, H.; Shingaki, N.; Moribata, K.; Deguchi, H.; Ueda, K.; Inoue, I.; Maekita, T.; Iguchi, M.; Kato, J.; et al. Signal intensity of small hepatocellular carcinoma on apparent diffusion coefficient mapping and outcome after radiofrequency ablation. Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. 2015, 45, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Tamai, H.; Shingaki, N.; Hayami, S.; Ueno, M.; Maeda, Y.; Moribata, K.; Deguchi, H.; Niwa, T.; Inoue, I.; et al. Hypointense hepatocellular carcinomas on apparent diffusion coefficient mapping: Pathological features and metastatic recurrence after hepatectomy. Hepatol. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hepatol. 2016, 46, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Kuge, Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nakada, K.; Sato, M.; Takei, T.; Tamaki, N. Biologic correlates of intratumoral heterogeneity in 18F-FDG distribution with regional expression of glucose transporters and hexokinase-II in experimental tumor. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2005, 46, 675–682. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, L.C.; Jin, Y.; Song, I.C.; Yu, S.; Zhang, K.; Chow, P.K. 2-[18F]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) uptake in human tumor cells is related to the expression of GLUT-1 and hexokinase II. Acta Radiol. 2008, 49, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojan, J.; Schroeder, O.; Raedle, J.; Baum, R.P.; Herrmann, G.; Jacobi, V.; Zeuzem, S. Fluorine-18 FDG positron emission tomography for imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Lee, M.; Yoo, J.J.; Choi, W.M.; Cho, Y.Y.; Paeng, J.C.; Kang, K.W.; Chung, J.K.; et al. Does 18F-FDG positron emission tomography-computed tomography have a role in initial staging of hepatocellular carcinoma? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Combs, C.S.; Brunt, E.M.; Lowe, V.J.; Wolverson, M.K.; Solomon, H.; Collins, B.T.; Di Bisceglie, A.M. Positron emission tomography scanning in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Paeng, J.C.; Kang, K.W.; Kwon, H.W.; Suh, K.-S.; Chung, J.-K.; Lee, M.C.; Lee, D.S. Prediction of Tumor Recurrence by 18F-FDG PET in Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detry, O.; Govaerts, L.; Deroover, A.; Vandermeulen, M.; Meurisse, N.; Malenga, S.; Bletard, N.; Mbendi, C.; Lamproye, A.; Honoré, P.; et al. Prognostic value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in liver transplantation for hepatocarcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3049–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Suh, K.-S.; Suh, S.-w.; Yoo, T.; Kim, H.; Park, M.-S.; Choi, Y.; Paeng, J.C.; Yi, N.-J.; Lee, K.-W. Alpha-fetoprotein and 18F-FDG positron emission tomography predict tumor recurrence better than Milan criteria in living donor liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Wang, C.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Yong, C.-C.; Wang, S.-H.; Liu, Y.-W.; Lin, T.-L.; Lee, W.-F.; Lin, Y.-H.; et al. Combination of FDG-PET and UCSF Criteria for Predicting HCC Recurrence After Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Transplantation 2016, 100, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.H.; Eo, J.S.; Lee, J.W.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, K.-H.; Na, S.J.; Hong, I.K.; Oh, J.K.; Chung, Y.A.; Song, B.-I.; et al. Prognostic value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages 0 and A hepatocellular carcinomas: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.J.; Choi, N.K.; Shin, M.H.; Chong, A.R. Clinical usefulness of FDG-PET in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Ann. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Surg. 2017, 21, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.H.; Eo, J.S.; Song, B.I.; Lee, J.W.; Na, S.J.; Hong, I.K.; Oh, J.K.; Chung, Y.A.; Kim, T.S.; Yun, M. Preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma using (18)F-FDG PET/CT: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoh, T.; Seo, S.; Ogiso, S.; Kawai, T.; Okuda, Y.; Ishii, T.; Taura, K.; Higashi, T.; Nakamoto, Y.; Hatano, E.; et al. Proposal of a New Preoperative Prognostic Model for Solitary Hepatocellular Carcinoma Incorporating 18F-FDG-PET Imaging with the ALBI Grade. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, J.W., Jr. SUV: Standard uptake or silly useless value? J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 1995, 36, 1836–1839. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Martinez, A.; Marin-Oyaga, V.A.; Salavati, A.; Saboury, B.; Codreanu, I.; Lam, M.G.E.H.; Torigian, D.A.; Alavi, A. Quantitative assessment of global hepatic glycolysis in patients with cirrhosis and normal controls using 18F-FDG-PET/CT: A pilot study. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2014, 28, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ida, Y.; Tamai, H.; Shingaki, N.; Shimizu, R.; Maeshima, S.; Maekita, T.; Iguchi, M.; Terada, M.; Kitano, M. Prognostic value of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma treated by radiofrequency ablation. Cancer Imaging Off. Publ. Int. Cancer Imaging Soc. 2020, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Baik, S.K.; Hong, I.S. The Clinical Implications of Liver Resection Margin Size in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Terms of Positron Emission Tomography Positivity. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Salloum, C.; Chalaye, J.; Lahat, E.; Costentin, C.E.; Osseis, M.; Itti, E.; Feray, C.; Azoulay, D. 18F-FDG PET/CT predicts microvascular invasion and early recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective observational study. HPB Off. J. Int. Hepato Pancreato Biliary Assoc. 2019, 21, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Suh, K.-S.; Lee, H.W.; Cho, E.-H.; Cho, J.Y.; Cho, Y.B.; Yi, N.-J.; Lee, K.U. The role of 18F-FDG-PET imaging for the selection of liver transplantation candidates among hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Liver Transplant. 2006, 12, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, A.; Freesmeyer, M.; Bärthel, E.; Jandt, K.; Katenkamp, K.; Steenbeck, J.; Sappler, A.; Habrecht, O.; Gottschild, D. 18F-FDG-Uptake of Hepatocellular Carcinoma on PET Predicts Microvascular Tumor Invasion in Liver Transplant Patients. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, Y.-K.; Park, S.-J. Clinical Impact of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in Living Donor Liver Transplantation for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Transplantation 2015, 99, 2142–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | N | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hatanaka et al. [28] | 29 | Solitary and ≤5 cm ≤3 tumors and ≤3 cm | LR | Gross type (SN type or non-SN type) | Sensitivity, 96%; specificity, 80%; accuracy, 90% |

| Li et al. [29] | 31 | Early stage | LR | Microvascular invasion | Non-SN type in the post-vascular phase image was an independent predictor of microvascular invasion (OR, 30.51; 95% CI, 2.335–398.731, p = 0.009). Sensitivity, 93.3%; specificity, 81.3%; positive predictive value, 82.4%; negative predictive value, 92.9% |

| Nuta et al. [30] | 73 | Solitary and ≤5 cm | LR | Gross type (SN type or non-SN type) Outcome (recurrence) | In the post-vascular phase, predictability for high-grade malignant potential was as follows: sensitivity was 93%, specificity was 85%, positive predictive value was 97%, negative predictive value was 73%, and accuracy was 92%. Irregular defect pattern was one of the independent factors for metastatic recurrence (HR, 4.388; 95% CI, 1.008–19.089; p = 0.049). |

| Study | n | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maruyama et al. [32] | 54 | Solitary and ≤5 cm ≤3 tumors and ≤3 cm | RFA | Outcome (Recurrence) | Intensity differences at the early arterial time is one of the independent factors for intrahepatic distant recurrence (HR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.2–5.8; p = 0.014). |

| Han et al. [33] | 125 | Solitary and 5 cm or less ≤3 tumors and ≤3 cm | RFA | Outcome (Recurrence) | Tumor peak intensity was a significant independent risk factor for intrahepatic recurrence after RFA (HR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.9). |

| Feng et al. [34] | 271 | Early stage | LR | Differentiation | Washout before 120 s from contrast injection group had poorly differentiation. Sensitivity, 98.0%; specificity, 77.8%; positive predictive value, 96.0%; negative predictive value, 48.8% |

| Yao et al. [35] | 211 | Early stage | LR | Microvascular invasion | Washout time (<90 s) (OR: 2.755, 95% CI: 1.227–6.187) was one of the independent predictors of microvascular invasion. |

| Study | n | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment (n) | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawamura et al. [40] | 191 | Solitary and ≤3 cm | Resection (60) RFA (131) | Outcome (recurrence) | The type 4 enhancement pattern was an independent factor for recurrence (HR, 27.68; 95% CI, 6.82–112.33; p < 0.001). |

| Nakachi et al. [41] | 223 | Early stage | Biopsy Resection | Differentiation | HCC with enhancement with non-enhanced area predicted poorly differentiation. Predictive value as follows; sensitivity was 85%, specificity was 76%, positive predictive value was 93%, negative predictive value was 97%, and accuracy was 77%. |

| Shimizu et al. [42] | 226 | ≤3 tumors and ≤3 cm | RFA | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | Heterogeneous enhancement pattern was one of the independent factors for critical recurrence (HR, 2.753; 95% CI, 1.453–5.219; p = 0.002) and related cancer death (HR, 2.369; 95% CI, 1.187–4.726; p = 0.014). |

| Study | n | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment (n) | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. [53] | 345 | Solitary and ≤3 cm | LR (123) RFA (222) | Outcome (recurrence) | In RFA group, non-hypervascular hypointense nodule was one of the independent factors for recurrence (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.20–2.63; p = 0.004). |

| Iwamoto et al. [54] | 91 | Early stage | RFA | Outcome (recurrence) | Non-hypervascular hypointense nodule was one of the independent factors for intrahepatic distant recurrence (HR, 4.37; 95% CI, 2.13–8.86; p < 0.01). |

| Toyoda et al. [55] | 77 | Early stage | LR | Outcome (recurrence) | Non-hypervascular hypointense nodule was an independent factor for multicentric recurrence (HR, 2.84; 95% CI, 1.69–4.84; p = 0.0002). |

| Toyoda et al. [56] | 138 | BCLC stage 0 or A | LR (76) RFA (62) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | Non-hypervascular hypointense nodule was an independent factor for recurrence (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.26–2.25; p = 0.0005) and which was one of the independent factors for OS (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.99–2.81; p = 0.05). |

| Bae et al. [57] | 183 | BCLC stage 0 or A | LR (61) RFA (61) TACE (61) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | In RFA group, existing satellite nodules was one of the independent factors for disease-free survival (HR, 5.04; 95% CI, 1.06–23.90; p = 0.04); moreover, peritumoral hypointensity (HR, 13.06; 95% CI, 1.63–104.84; p = 0.02) and existing satellite nodules (HR, 9.40; 95% CI, 1.48–59.67; p = 0.02) on HBP were related to OS. |

| Study | n | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment (n) | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mori et al. [68] | 136 | ≤3 tumors and ≤3 cm | RFA | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | Hypointensity on the ADC map was one of the independent factors for recurrence (HR, 2.651; 95% CI, 1.530–4.593; p = 0.001), local recurrence (HR, 5.602; 95% CI, 1.526–20.568; p = 0.009), critical recurrence (HR, 2.555; 95% CI, 1.171–5.571; p = 0.018), and survival (HR, 2.945; 95% CI, 1.124–7.721; p = 0.028). |

| Mori et al. [69] | 52 | Solitary and ≤5 cm | LR | Outcome (recurrence) | Hypointensity on the ADC map was one of the independent factors for metastatic recurrence (HR, 12.279; 95% CI, 1.486–101.48; p = 0.020). |

| Study | n | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment (n) | Point of View | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. [75] | 59 | Milan criteria (within/beyond) | LTP | TSUVmax/LSUVmax (cutoff value; 1.15) | Outcome (recurrence) | Significantly difference was seen about recurrence-free survival. TSUVmax/LSUVmax < 1.15; the 1 year and 2 year recurrence-free survival rate was 97% and 97%, respectively. TSUVmax/LSUVmax ≥ 1.15; the 1 year and 2 year recurrence-free survival rate was 57% and 42%, respectively. |

| Detry et al. [76] | 27 | Milan criteria (within/beyond) | LTP | TSUVmax/LSUVmax (cutoff value; 1.15) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | TSUVmax/LSUVmax > 1.15 was one of the independent factors for recurrence-free survival (HR, 14.4; p = 0.01) and overall survival (HR, 5.62; p = 0.04). |

| Hong et al. [77] | 123 | Milan criteria (within/beyond) | LTP | TSUVmax/LSUVmax (cutoff value; 1.10) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | TSUVmax/LSUVmax > 1.10 was an independent factor for recurrence (HR, 9.776; 95% CI, 3.557–26.816; p < 0.001). |

| HSU et al. [78] | 147 | “Solitary and ≤6.5 cm” or “≤3 tumors and ≤4.5 cm” and total tumor diameter ≤8 cm | LTP | TNR (cutoff value; 2.0) | Outcome (recurrence) | TNR ≥ 2.0 was one of the independent factors for recurrence (HR, 13.52; 95% CI, 4.77–38.29; p < 0.001). |

| Hyun et al. [79] | 317 | BCLC stage 0 or A | Curative treatment (LR or RFA or LTP) (195) TACE (122) | TLR (cutoff value; 2.0) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | TLR ≥ 2.0 was an independent factor for OS in curative treatment group (HR, 2.68; 95% CI, 1.16–6.15; p = 0.020). |

| Cho et al. [80] | 56 | Early stage | LR | SUVmax (cutoff value; 4.9) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | SUVmax was not significant independent factor for recurrence (p = 0.262) and OS (p = 0.717). |

| Hyun et al. [81] | 158 | BCLC stage 0 or A | LR | TLR (cutoff value; 1.3) | Microvascular invasion Outcome (recurrence) | Predictability of TLR for microvascular invasion as follows: sensitivity was 85.5%, specificity was 54.9%, positive predictive value was 63.7%, negative predictive value was 80.4%. TLR was one of the independent factors for metastatic recurrence (HR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.01–5.84; p = 0.047). |

| Yoh et al. [82] | 207 | Solitary | LR | TNR (cutoff value; 2.0) | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | TNR was one of the independent factors for OS (HR, 1.743; 95% CI, 1.114–2.648; p = 0.016). |

| Study | n | Inclusion Criteria of Tumor | Treatment (n) | Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ida et al. [85] | 121 | ≤3 tumors and ≤3 cm | RFA | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | PET positivity was one of the independent factors for metastatic recurrence (HR, 10.297; 95% CI, 3.128–33.898; p < 0.001) and OS (HR, 7.300; 95% CI, 1.920–27.751; p = 0.004). |

| Park et al. [86] | 92 | Early stage | LR | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | PET positivity was one of the independent factors for disease-free survival (HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.273–6.158; p = 0.01). In PET-positive HCC, OS of narrow resection margin group was significantly shorter than that of wide resection margin group (p < 0.001). |

| Lim et al. [87] | 78 | Early stage | LR | Microvascular invasion Outcome (recurrence) | Predictability of PET for microvascular invasion of as follows: sensitivity was 62%, specificity was 76%, positive predictive value was 71%, and negative predictive value was 53%, respectively. PET positive was one of the independent factors for early recurrence (HR, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.6–20.4; p = 0.006). |

| Yang et al. [88] | 38 | Milan criteria (within/beyond) | LTP | Outcome (recurrence) | The association between PET positivity and tumor recurrence was significant (p = 0.003). The 2-year recurrence-free survival rates for the PET-positive group and PET-negative group were 46.1% and 85.1%, respectively (p = 0.0005). |

| Kornberg et al. [89] | 42 | Milan criteria (within/beyond) | LTP | Microvascular invasion Outcome (recurrence) | PET positivity was an independent factor for microvascular invasion (HR, 13.4; 95% CI, 0.003–0.126; p = 0.001). The 3-year recurrence-free survival rates beyond the Milan criteria/PET-negative group and beyond the Milan criteria/PET-positive group were 94% and 29%, respectively (p < 0.001). |

| Lee et al. [90] | 280 | Milan criteria (within/beyond) | LTP | Outcome (recurrence, OS) | In patients beyond the Milan criteria, PET positivity was one of the independent factors for recurrence-free survival (HR, 3.803; 95% CI, 1.876–7.707; p < 0.001) and OS (HR, 2.714; 95% CI, 1.239–5.948; p = 0.013). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimizu, R.; Ida, Y.; Kitano, M. Predicting Outcome after Percutaneous Ablation for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Various Imaging Modalities. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13193058

Shimizu R, Ida Y, Kitano M. Predicting Outcome after Percutaneous Ablation for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Various Imaging Modalities. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(19):3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13193058

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimizu, Ryo, Yoshiyuki Ida, and Masayuki Kitano. 2023. "Predicting Outcome after Percutaneous Ablation for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using Various Imaging Modalities" Diagnostics 13, no. 19: 3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13193058