1. Introduction

A decade has passed since I published

Destinies of the Disadvantaged: The Politics of Teenage Childrearing, the final volume in a trilogy of books on the findings of a 30-year longitudinal study of teen mothers and their offspring in Baltimore [

1]. The Baltimore Study was begun in the mid-1960s when America, like many other Western nations, was on the cusp of a huge revolution in the family. Marriage was just beginning its half-century retreat, at least for all but the well-educated, and non-marital childbearing was starting to attract some attention in public health and family planning circles. The final wave of interviews, completed in the mid-1990s, took place after rates of teenage childbearing had already begun to drop in the United States, a trend that has continued nearly uninterrupted to the present day.

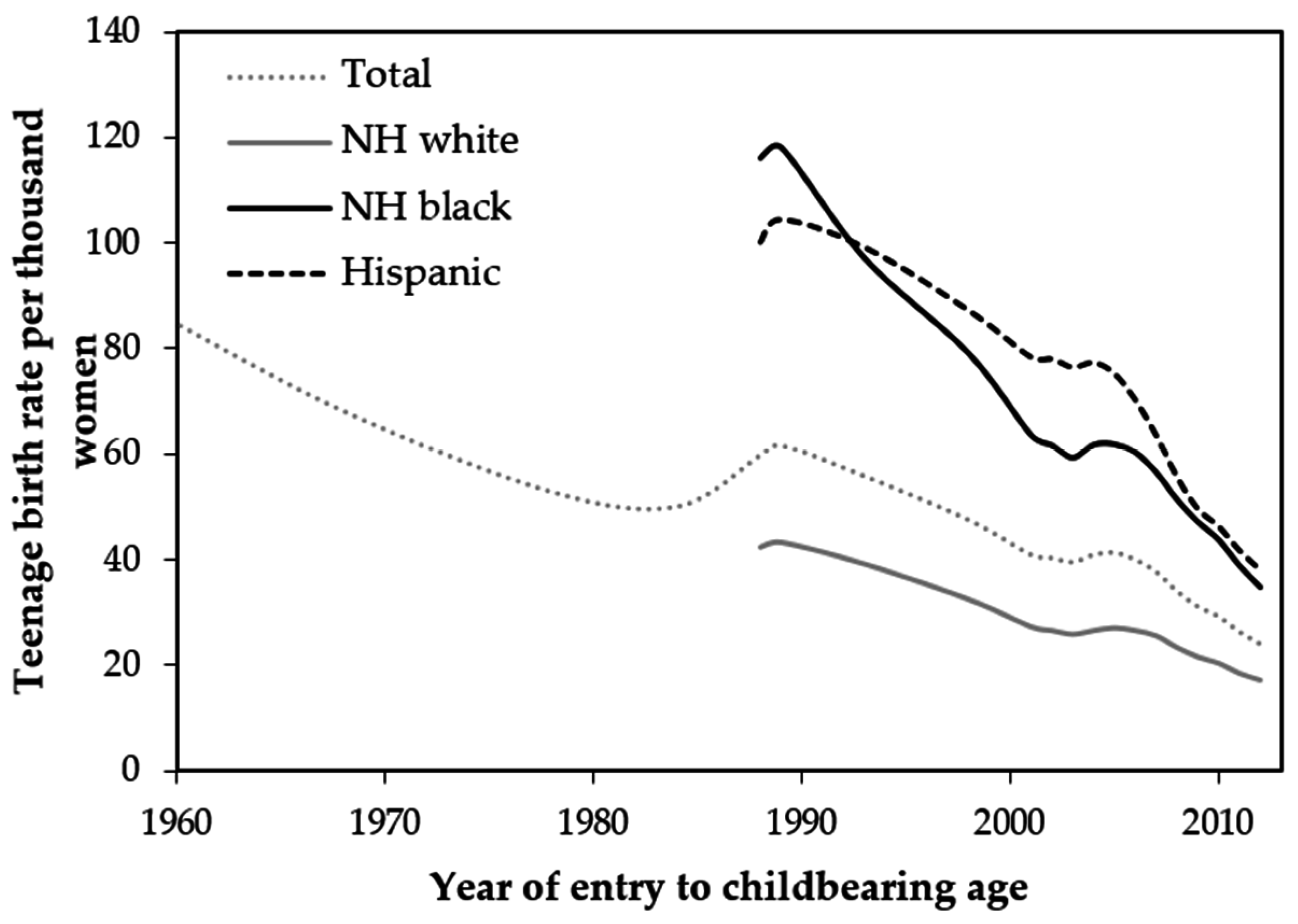

The decline in teenage childrearing over the past half century has been nothing short of spectacular: falling from 90 per 1000 in 1960 to 26.5 per 1000 in 2013. Initially, teenagers began to curtail childbearing in part because it became increasingly untenable for them to marry in the event of a pregnancy as they had done throughout the post-war period. This initial decline, beginning in the 1960s, slowed and then reversed in the 1980s, when liberalized abortion policies were reversed and sex education became more controversial during the Reagan presidency (see

Figure 1) [

2]. This was the period when cultural conservatives mounted a strong campaign to reduce early childbearing by discouraging sexual initiation through “abstinence only” programs, a policy approach that proved to be almost totally ineffective and perhaps even counterproductive in delaying premarital sex and preventing unwanted conceptions [

3,

4].

After stalling in the 1980s and even reversing for several years from 1988 to 1991, the rate of teen childbearing resumed its downward direction and has continued to decline to the present. The current rate is less than half of what was at its recent high point in 1991 [

6]. Hardly any experts in the field would have predicted the sharp decline since the early 1990s when President Clinton, in a bit of hyperbole, called early childbearing the most urgent problem facing this country [

7].

This brief commentary begins by reiterating the most important lessons learned from research about the causes and consequences of early childbearing. Then I will turn to some observations about events during the past decade that have helped to bring about the reduction in early childbearing. I conclude with a discussion of future policy initiatives, assuming, as I do, that further delays in the timing of first parenthood will not inevitably bring about an improvement in the economic and social circumstances of disadvantaged young adults.

2. What We Now Know about the Impact of Early Childbearing

By the time that I completed my 30-year study following the life course of 323 teen mothers and their children (out of an original sample of 404), there was growing evidence from a number of studies, consistent with the findings of the Baltimore Study, that politicians, policy makers, and researchers had largely misdiagnosed the problem of teenage childbearing (see, for example, [

8]). I, among other researchers, concluded that teenage childbearing was not a root “cause” of social disadvantage, as many social scientists had initially believed, but largely a marker of under-privilege or a concomitant of growing up poor and, in many cases, a member of a disadvantaged minority (see, for example, [

9,

10]).

It is certainly true that most teenage parents and their children are likely to be mired in poverty throughout much of their lives, but many of their counterparts who delayed early childbearing in the Baltimore sample and in national studies are not notably better off once we take full account of social and personal circumstances leading up to the occurrence of a pregnancy and birth in their teens. Being poor, in a disadvantaged minority group, attending inner-city schools, exclusively associating with peers who are similarly situated, and a host of other liabilities associated with under-privilege both generated high rates of early childbearing and continuing economic and social disadvantage. Having a child early in life certainly does not make things better and it may well create added complications for the teen, her partner, and the child, but much and probably most of the damage to the young mother’s prospects has already been done by the time the pregnancy occurs.

Early parenthood occurs as a result of a process of social selection, or what I described in the first volume of the Baltimore Study as “selective recruitment” to early parenthood [

11]. This selection process, more than the actual event of early parenthood itself, creates the long shadow of social disadvantage. This means that unless we address the conditions that lead up to parenthood, we cannot hope to change the destinies of the disadvantaged whether they have a birth in early life or not.

This stark conclusion must be tempered to some extent by noting that the lives of teen mothers and their offspring unfolded differently among the families that I studied. Not all the young mothers, their partners, and their families reacted to early parenthood identically. How they responded to the birth of their first child also shaped their life course and how their children fared in later life. These heterogeneous reactions to entering parenthood are one of the reasons that teen mothers do not look very different from their counterparts who delayed children. Put differently, many young mothers were able to get back on track despite the challenging circumstances created by having a birth in the teen years. Others did poorly, but many of those had already exited school and faced enormous obstacles to becoming economically independent.

In the Baltimore Study, I identified several responses or adaptations to early childbearing that affected the lives of the parents and children for better and for worse:

1. Returning to school after their children were born and increasing their educational attainment in significant ways is the first of these adaptations. Of course, the more able students were more likely to return; going back to school also required the assistance of parents or, occasionally, partners. Those who made significant educational advancements were far more likely to enter the middle class than those whose schooling ended with the birth of their first child. Their children were also more likely to succeed in school and stay out of trouble. Over the course of the study, the great majority of the young mothers returned to school, sometimes a decade or two after their first child was born. So motivation for getting ahead through education matters greatly in the long run. Surprisingly, a tenth of the teen mothers eventually graduated from college, and an additional quarter had entered college but never graduated, at least by their mid-forties. Few, including me, would have expected the delayed route to educational attainment to be so significant in shaping the fate of the women and their children in the study.

2. Curtailing their fertility after the first birth is the second adaptation by young mothers that contributes to their subsequent success. Contrary to expectation, most teen mothers do not go on to have large families, as was often portrayed in the early literature on the topic. “The myth of the brood sow” was what a pair of researchers many years ago referred to the popular stereotype of poor women having babies to remain on public assistance [

12]. In the Baltimore Study, only a small minority of mothers went on to have more than three children. Over half (62%) either never had another child or had only one additional birth during the course of the study. Fertility control was associated with returning to school and a higher level of participation in the labor force. Many of the young mothers, even those with lower fertility, opted for sterilization in their 20s and early 30s because they continued to have difficulty using available contraceptive methods, especially birth control pills.

3. The third adaptation, related to the success of the young mothers, was avoiding an early marriage. Women who married before or soon after their first child was born were less likely to return to school and were more likely to have subsequent births. Resisting early marriage, after becoming pregnant, in the mid-1960s was still relatively uncommon, even for African-Americans who comprised four- fifths of the original sample. Over half of the teens married the father of their first child, but only one in five of these marriages was still intact 30 years later. Women who married before or soon after their first birth “to give their child a name”, as some explained their decision, were no less likely eventually to become single mothers than those who delayed matrimony, usually marrying a partner who was not the father of her first child. Moreover, many of the women who married swiftly left school to do so, thereby compromising their chances of economic independence when their marriages eventually dissolved. Women who married soon after their first child was born were also more likely to have additional children, complicating their prospects of attaining financial independence from their family.

4. Significantly, the receipt of public assistance, “welfare” as it was known then, was not a factor in the long-term success of young mothers. Those who persisted on welfare for long spells, not surprisingly, did worse as adults, but short-term use of welfare, because it was often associated with further schooling and job training, contributed to success in later life as measured by economic independence and the successful development of the first-born child at the time of the 30-year follow up.

5. Similarly, co-residence with the natal family had a contingent association with long-term success. Short-term reliance on the family was associated with greater educational attainment, but long-term reliance had the opposite effect of signaling the inability to gain financial autonomy either through schooling and entrance into the labor force or controlling subsequent fertility.

6. Finally, paternal involvement in the children’s lives also produced mixed results. When fathers actively participated by providing material and emotional support, the children were generally better off, but sporadic participation could be worse than no involvement at all. The majority of the offspring were faring reasonably well at the 30-year follow up. However, the educational and labor market success of the first-born daughters was notably higher than the first-born sons whose extensive experience in the criminal justice system had scarred their entrance to adulthood.

There is scant evidence showing that interventions specifically tailored to help mothers persist in school, control their fertility, and gain financial independence helped much to mitigate the postnatal adjustment of teen mothers or their partners. As much as policy makers and service providers have tried to develop effective program models targeted at teens who have already had a child, there is relatively little to show in the way of direct impacts on the life course of young mothers from the vast number that have been developed to assist teen mothers, their families, and their offspring. This is not to say that well-designed programs could not achieve results in moderating the impact of an early first birth, but the programs that have been evaluated have generally not been notably effective.

By far, the most powerful and effective measure for reducing teen parenthood and its potential adverse impacts has been the development of effective reproductive health services that prevent unwanted first births (and subsequent ones) from occurring. This finding takes on special relevance today when reproductive health programs for women have once again become politically controversial.

3. Recent Advances in Reproductive Health and the Prevention of Teen Pregnancy

As mentioned earlier, only about half as many teens become pregnant and have children today as they did just 25 years ago. What explains this steep decline in fertility among teens (and women in their early twenties)? The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), conducted by the Center for Disease Control (CDC), has reported on sexual behavior and contraceptive use for students for a national sample of 10th graders since 1991 to 2015, the most recent year of data collection. It is instructive to examine the trends over the past nearly quarter of a century, the period in which early childbearing has plunged. The data show a significant decline in the incidence of students reporting that they had ever had sexual intercourse from 54.1% in 1991 to 41.2% in 2015, a drop of about 25%. Those currently sexually active in the past three months declined during the same period from 37.5% to 30.1%, strongly suggesting that a reduction of sexual activity is part of the explanation for the decline in teen pregnancy [

13,

14].

Another large part of the decline has been an increase in contraceptive practice, especially in the use of new, hormonal methods that are more reliable and easier to use than birth control pills, the preferred method of contraception for females 25 years ago. Overall, the YBRS shows that teens have both become more willing to use condoms when they have sex. and they also are much more likely to be using newer and more reliable forms of contraception such as the patch, depropravara, implants, and newer forms of the intrauterine devices (IUD’s). Most recently, morning-after pills have now become available over the counter, increasing the repertoire of methods of preventing conception. As a result of the introduction of these more reliable and user-friendly methods, it appears that sexually active teens have become much more adept at preventing pregnancies through effective use of contraception [

15].

There are a number of reasons why sexually active teens have become better contracepters. First, they are much more aware than their counterparts were 25 years ago that marriage is no longer available as a comfortable safety net should a pregnancy occur. Young people now realize, more than they did in the past, that their sexual partners are often not able to assume the responsibilities of supporting a family because they are too young and often lack the skills to enter the labor market [

16]. Accordingly, early marriage among teenagers has virtually disappeared in the past 25 years [

17]. Finally, as the age of women at the birth of their first child has risen, early childbearing has become a more discrepant practice because teenagers are increasingly aware of the difficulty of managing parenthood before they can complete their schooling and find a job. Most who became pregnant in the past, just as today, were not seeking to become parents. While unintended pregnancies are still common today, many more teens now, I suspect, are aware of the potential challenges of parenthood before they are ready to support a family. This applies both to young women and young men, who now realize that they are likely to be responsible for paying child support if and when they find employment. Moreover, it has become more important for fathers to be a “good dad” who is involved with their children; accordingly, women have become more reluctant to share parental responsibilities with partner who fails to assist financially and emotionally. This higher standard of parenting may have helped to discourage men from entering fatherhood casually.

It is possible, though undemonstrated, that the more restrictive climate surrounding the availability of abortion could be motivating teens to take measures to prevent a pregnancy from occurring. It is also possible that more teens are resorting to newly available methods of contraception such as the post-coital, “morning-after” pill to prevent conception from occurring. It is certainly the case that the array of newer contraceptive methods has made using reliable means of birth control far more available than was the case 25 years ago. Of course, local restrictions in both sex education and contraceptive availability in many areas of the United States still provide barriers to the practice of contraception, not to mention the increased barriers to abortion that have been erected since Rowe v. Wade in 1973.

Sexually active youth in the United States are beginning to resemble their counterparts in other countries with advanced economies who have long treated early sexual activity as a public health rather than a moral issue. Still, we continue to maintain relatively high rates of early childbearing compared to Europe and the other Anglo-speaking countries because of, in large part, political opposition to free reproductive health for young people. The state-to-state variation in rates of teenage pregnancy and childbearing in the United States is enormous. Several states, for example Maine and Connecticut, have lower rates of early childbearing than Canada and a number of Western European nations, but in others the incidence of early childbearing remains high. Moreover, the variation within states and cities is at least as great as the variation between them [

18].

The availability of more effective and user-friendly methods of contraception has increased contraceptive practice and had considerable success in bringing down the rate of early childbearing despite the lagging efforts in parts of this country.

The success, imperfect as it has been, in reducing early childbearing raises a critical question that has not yet been answered: has this policy success led young women and the men who were their partners to experience greater educational attainment and a better position in the labor market? Has the reduction of early childbearing actually eased the burden on families by creating less fragile partnerships? Has it increased the success of children born to partnerships that are formed later in life?

These are not easy questions to answer empirically because other conditions have eroded the economic fortunes of young adults over the past quarter of a century, especially among those who grow up in disadvantaged families. The lingering impact of the Great Recession and the rising costs of higher education may well have offset whatever gains would have occurred had conditions that prevailed in the 1990s continued today.

Apart from the long tail of the Great Recession, it takes young people longer today to gain financial independence than it did three decades ago [

19]. So, the theoretical gains achieved by delaying parenthood, if there were any to be had, may not have produced brighter futures for disadvantaged youth simply because their prospects are not as good as they were in the 1990s. In any case, more favorable outcomes for disadvantaged youth could not be anticipated

unless the later timing of first births was due to additional schooling and labor market experience in the interim.

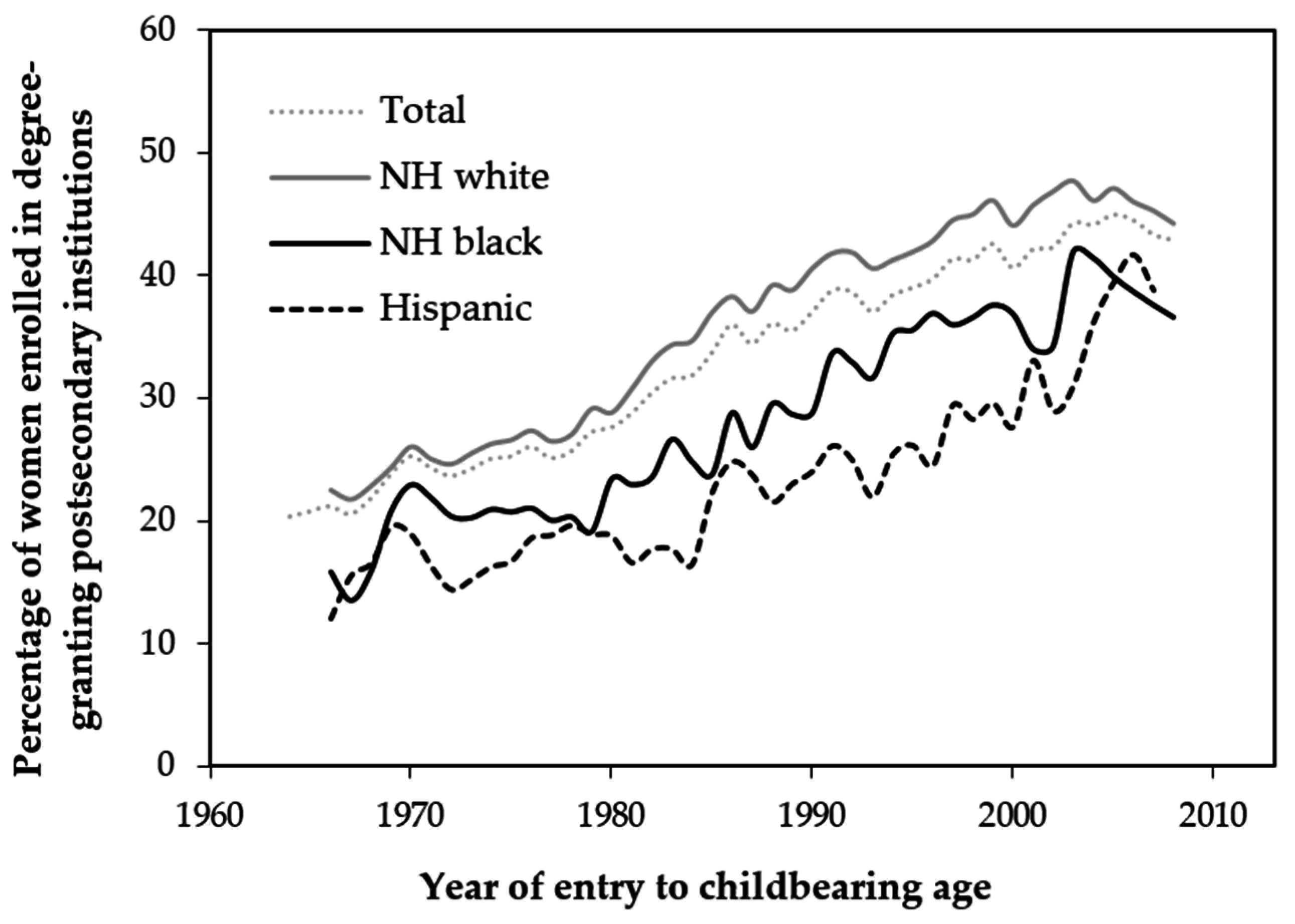

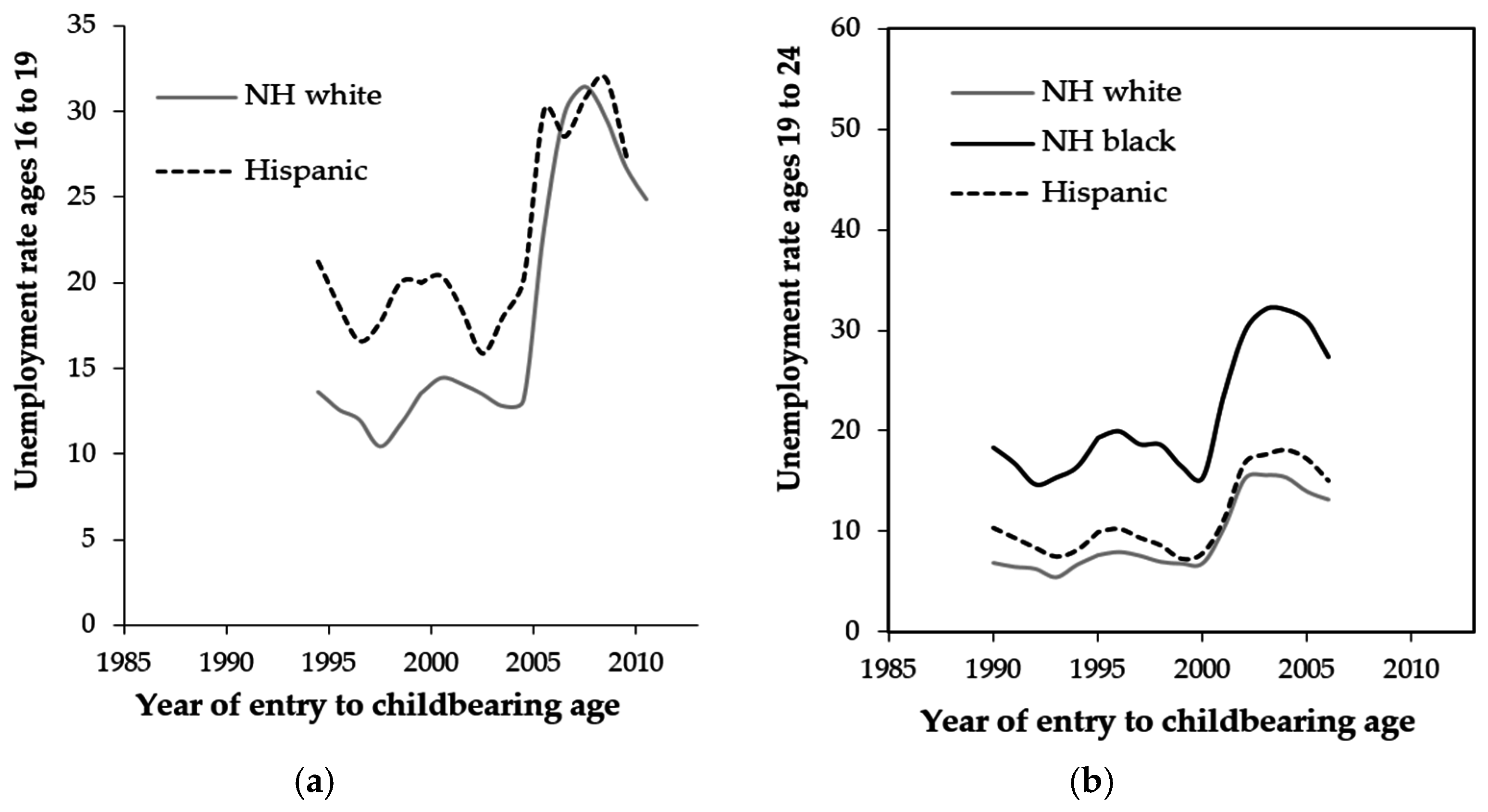

A cursory glance at the descriptive data reveals that young adults who come from economically disadvantaged families and grow up in poor neighborhoods are not making notable advances either in schooling or in the work place (See

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Moreover, there are

more, not

fewer, children living in poverty than was the case a decade ago. Declining economic fortunes of low-income families is surely part of the explanation (maybe all of it), but nonetheless, it is difficult to make a strong case that advancing the age of first birth has paid off in the reduction of economic disadvantage. If the economy begins to provide more and better-paying jobs to those with low and moderate education, then young adults could be better positioned to gain economic autonomy and could perhaps be in a better position to form stable partnerships capable of providing support for children. At present, we seem far from that prospect.