Understanding the Recovery of Rare-Earth Elements by Ammonium Salts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterisation and Computational Techniques

2.3. Synthesis of Trioctylmethylammonium Nitrate (IL)

2.4. General REE Recovery Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

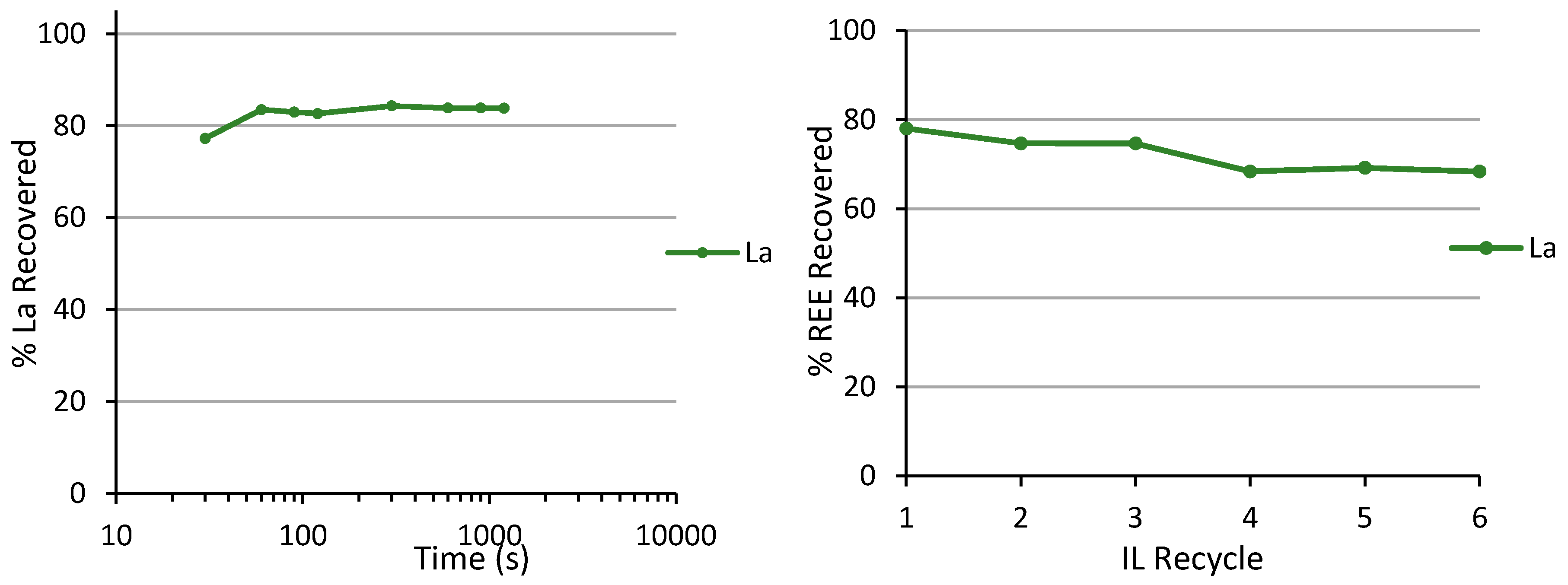

3.1. Solvent Extraction of La, Nd, and Dy by IL

3.2. Evaluation of the Mechanism of Ln Recovery by IL

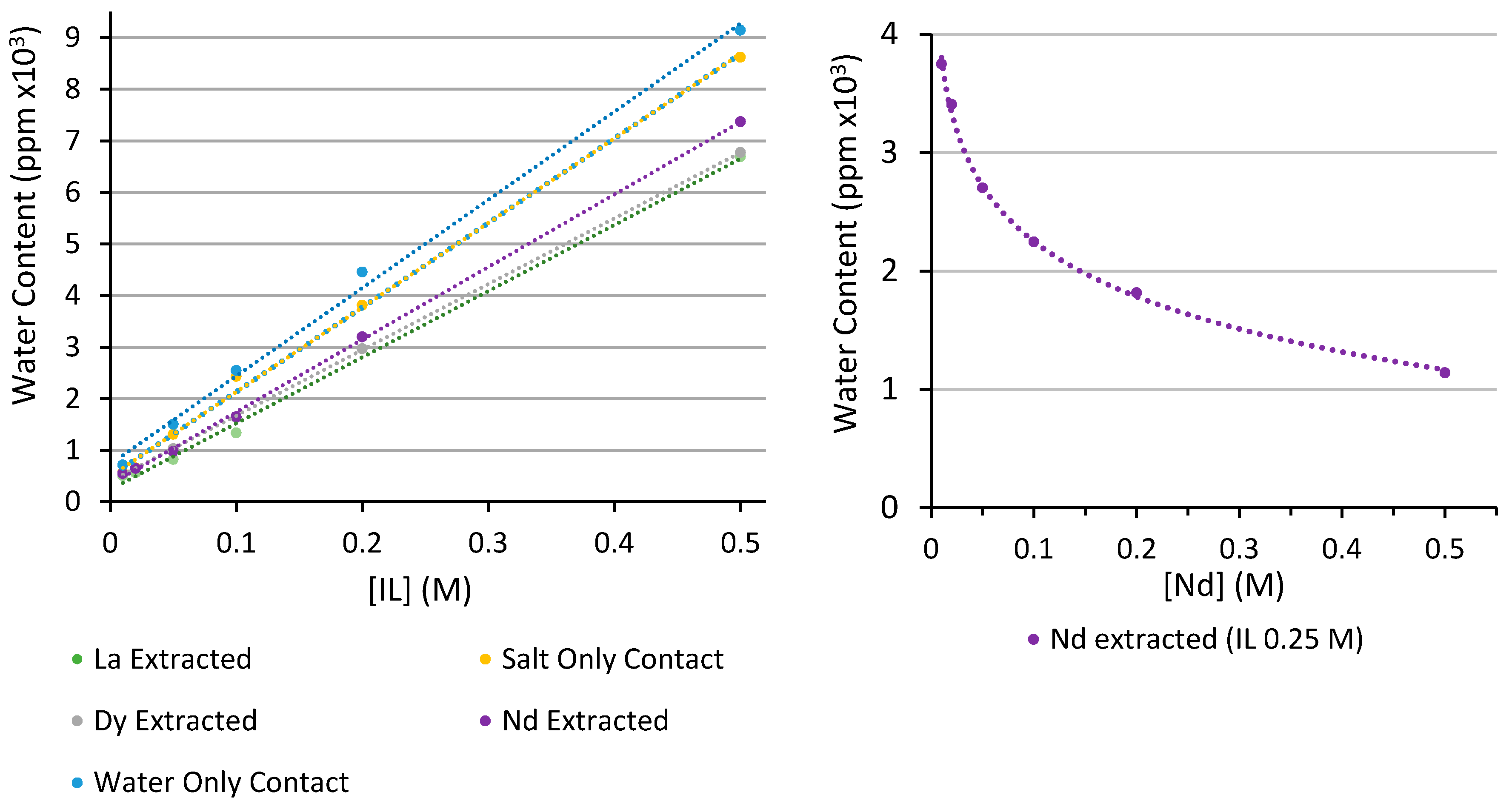

3.2.1. Karl-Fischer Analysis of Water Content

3.2.2. Nitric Acid and Nitrate Transport by IL

3.2.3. Characterization by Mass Spectrometry and La NMR Spectroscopy

3.2.4. Structural Analysis by Computational Modelling

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogers, R.D.; Seddon, K.R. Ionic Liquids—Solvents of the Future? Science 2003, 302, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Adidharma, H.; Radosz, M.; Wan, P.; Xu, X.; Russell, C.K.; Tian, H.; Fan, M.; Yu, J. Recovery of rare earth elements with ionic liquids. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 4469–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.H.; Zhao, J.M.; Li, Y.B.; Mehio, N.; Qi, Y.R.; Liu, H.Z.; Dai, S. An ionic liquid-based synergistic extraction strategy for rare earths. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2981–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Mishra, S. Studies on solvent extraction of La(III) using A336-NO3 and modeling by statistical analysis and neural network. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 1660–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.R.V.; Venkatesan, K.A.; Rout, A.; Srinivasan, T.G.; Nagarajan, K. Potential Applications of Room Temperature Ionic Liquids for Fission Products and Actinide Separation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.Q.; Ji, Y.; Guo, L.; Chen, J.; Li, D.Q. A novel ammonium ionic liquid based extraction strategy for separating scandium from yttrium and lanthanides. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 81, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, A.E.; Rogers, R.D. Room-temperature ionic liquids: New solvents for f-element separations and associated solution chemistry. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 171, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocalia, V.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Holbrey, J.D.; Spear, S.K.; Stepinski, D.C.; Rogers, R.D. Identical extraction behavior and coordination of trivalent or hexavalent f-element cations using ionic liquid and molecular solvents. Dalton Trans. 2005, 1966–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, N.; Gupta, C.K. Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.H.; Chen, J.; Li, D.Q. Application and Perspective of Ionic Liquids on Rare Earths Green Separation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Neuefeind, J.; Beitz, J.V.; Skanthakumar, S.; Soderholm, L. Mechanisms of Metal Ion Transfer into Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids: The Role of Anion Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15466–15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, H.; Aoyagi, N.; Shimojo, K.; Naganawa, H.; Imura, H. Role of Tf2N-anions in the ionic liquid-water distribution of europium(iii) chelates. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 7610–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, M. What Is Aliquat® 336 and Adogen® 464 HF? Let’s Clear up the Confusion. Available online: http://phasetransfer.com/WhatisAliquat336andAdogen464.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Padhan, E.; Sarangi, K. Recovery of Nd and Pr from NdFeB magnet leachates with bi-functional ionic liquids based on Aliquat 336 and Cyanex 272. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 167, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, A.; Venkatesan, K.A.; Srinivasan, T.G.; Rao, P.R.V. Ionic liquid extractants in molecular diluents: Extraction behavior of europium (III) in quarternary ammonium-based ionic liquids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 95, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Sinha, M.K.; Sahu, S.K.; Pandey, B.D. Solvent Extraction and Separation of Trivalent Lanthanides Using Cyphos IL 104, a Novel Phosphonium Ionic Liquid as Extractant. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2016, 34, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, D.; Depuydt, D.; Binnemans, K. Overview of the Effect of Salts on Biphasic Ionic Liquid/Water Solvent Extraction Systems: Anion Exchange, Mutual Solubility, and Thermomorphic Properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 6747–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, J.S. The recovery of rare earth oxides from a phosphoric acid byproduct. Part 4. The preparation of magnet-grade neodymium oxide from the light rare earth fraction. Hydrometallurgy 1996, 42, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, C.A.; Ciminelli, V.S.T. Selection of solvent extraction reagent for the separation of europium(III) and gadolinium(III). Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K.; Binnemans, K. Separation of Rare Earths by Solvent Extraction with an Undiluted Nitrate Ionic Liquid. J. Sustain. Metall. 2017, 3, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černá, M.; Bízek, V.; Št’astová, J.; Rod, V. Extraction of nitric acid with quaternary ammonium bases. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1993, 48, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, I.M.; Weeden, D.H. Isotropic nuclear magnetic resonance shifts in ion-paired systems. Penta- and hexanitratolanthanate(III) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1973, 12, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagreev, V.V.; Popov, S.O. NMR study of extracted compounds of trioctylalkylammonium with rare earth nitrates. Polyhedron 1985, 4, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.H.; Huang, Y.; Boatz, J.A.; Shreeve, J.N.M. Energetic Ionic Liquids based on Lanthanide Nitrate Complex Anions. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 11167–11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.J.; Ahern, J.C.; Patterson, H.H.; Leznoff, D.B. Ce/Au(CN)2−-Based Coordination Polymers Containing and Lacking Aurophilic Interactions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 2082–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesman, A.S.R.; Turner, D.R.; Deacon, G.B.; Batten, S.R. Tetramethylammonium hexanitratoneodymiate(III). Structural variations of the [Nd(NO3)6]3− anion in a single crystal. J. Coord. Chem. 2007, 60, 2191–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, M.G.B.; Hudson, M.J.; Iveson, P.B.; Russell, M.L.; Liljenzin, J.-O.; Sklberg, M.; Spjuth, L.; Madic, C. Theoretical and experimental studies of the protonated terpyridine cation. Ab initio quantum mechanics calculations, and crystal structures of two different ion pairs formed between protonated terpyridine cations and nitratolanthanate(III) anions. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1998, 2973–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tian, G.; Rao, L. Effect of Solvation? Complexation of Neodymium(III) with Nitrate in an Ionic Liquid (BumimTf2N) in Comparison with Water. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2013, 31, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.; Liu, L.S.; Dau, P.D.; Gibson, J.K.; Rao, L.F. Unusual complexation of nitrate with lanthanides in a wet ionic liquid: A new approach for aqueous separation of trivalent f-elements using an ionic liquid as solvent. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 37988–37991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Hoogerstraete, T.; Binnemans, K. Highly efficient separation of rare earths from nickel and cobalt by solvent extraction with the ionic liquid trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium nitrate: A process relevant to the recycling of rare earths from permanent magnets and nickel metal hydride batteries. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidge, E.D.; Carson, I.; Love, J.B.; Morrison, C.A.; Tasker, P.A. The Influence of the Hofmeister Bias and the Stability and Speciation of Chloridolanthanates on Their Extraction from Chloride Media. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2016, 34, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, I.; MacRuary, K.J.; Doidge, E.D.; Ellis, R.J.; Grant, R.A.; Gordon, R.J.; Love, J.B.; Morrison, C.A.; Nichol, G.S.; Tasker, P.A.; et al. Anion Receptor Design: Exploiting Outer-Sphere Coordination Chemistry to Obtain High Selectivity for Chloridometalates over Chloride. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 8685–8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.M.; Bailey, P.J.; Tasker, P.A.; Turkington, J.R.; Grant, R.A.; Love, J.B. Solvent extraction: The coordination chemistry behind extractive metallurgy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doidge, E.D.; Carson, I.; Tasker, P.A.; Ellis, R.J.; Morrison, C.A.; Love, J.B. A Simple Primary Amide for the Selective Recovery of Gold from Secondary Resources. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12436–12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Maxwell, D.S.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and Testing of the OPLS All Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E.; Martinez, J.M. PACKMOL: A Package for Building Initial Configurations for Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nosé, S. A Unified Formulation of the Constant Temperature Molecular Dynamics Methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W.G. Canonical Dynamics: Equilibrium Phase-Space Distributions. Phys. Rev. A 1985, 31, 1695–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Rani, M.A.; Borduas, N.; Colquhoun, V.; Hanley, R.; Johnson, H.; Larger, S.; Lickiss, P.D.; Llopis-Mestre, V.; Luu, S.; Mogstad, M.; et al. The potential of methylsiloxanes as solvents for synthetic chemistry applications. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1282–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, F.; Zhang, T.A.; Dreisinger, D.; Doyle, F. A critical review on solvent extraction of rare earths from aqueous solutions. Miner. Eng. 2014, 56, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkaman, R.; Moosavian, M.A.; Torab-Mostaedi, M.; Safdari, J. Solvent extraction of samarium from aqueous nitrate solution by Cyanex301 and D2EHPA. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 137, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.E.; Soldenhoff, K.H.; Stevens, G.W.; Lengkeek, N.A. Solvent extraction of rare earth elements using phosphonic/phosphinic acid mixtures. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 157, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, S.; Shafaie, S.Z.; Goudarzi, N. Investigation of performances of solvents D2EHPA, Cyanex272, and their mixture system in separation of some rare earth elements from a Nitric Acid solution. J. Min. Environ. 2016, 7, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Kumari, A.; Panda, R.; Kumar, J.R.; Yoo, K.; Lee, J.Y. Review on hydrometallurgical recovery of rare earth metals. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 165, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Kuang, W.Q.; Zhao, J.M.; Liu, H.Z. Ionic liquid-based synergistic extraction of rare earths nitrates without diluent: Typical ion-association mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 179, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, A.; Keppler, B.K. Ionic Liquids as Extracting Agents for Heavy Metals. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 47, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, H.; Meng, S.L.; Li, D.Q. Solvent extraction of lanthanides and yttrium from nitrate medium with CYANEX 925 in heptane. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 2007, 82, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, R.; Jeon, H.; Lee, M. Solvent extraction separation of Pr and Nd from chloride solution containing La using Cyanex 272 and its mixture with other extractants. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2012, 98, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRuary, K.J.; Gordon, R.J.; Grant, R.A.; Woollam, S.; Ellis, R.J.; Tasker, P.A.; Love, J.B.; Morrison, C.A. On the Extraction of HCl and H2PtCl6 by Tributyl Phosphate: A Mode of Action Study. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2017, 35, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, S.; Modolo, G.; Madic, C.; Testard, F. Aggregation properties of N,N,N′,N′-tetraoctyl-3-oxapentanediamide (TODGA) in n-dodecane. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2004, 22, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, M.R.; McAlister, D.R.; Horwitz, E.P. An europium(III) diglycolamide complex: Insights into the coordination chemistry of lanthanides in solvent extraction. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R.J. Acid-switched Eu(III) coordination inside reverse aggregates: Insights into a synergistic liquid-liquid extraction system. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2017, 460, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.; Pathak, P.N.; Husain, M.; Prasad, A.K.; Parmar, V.S.; Manchanda, V.K. Extraction of actinides using N,N,N′,N′-tetraoctyl diglycolamide (TODGA): A thermodynamic study. Radiochim. Acta 2006, 94, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.J.; Meridiano, Y.; Chiarizia, R.; Berthon, L.; Muller, J.; Couston, L.; Antonio, M.R. Periodic Behavior of Lanthanide Coordination within Reverse Micelles. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 2663–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacox, M.E. Vibrational and electronic energy levels of polyatomic transient molecules. Supplement B. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2003, 32, 1–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.F.; Missen, P.H. La-139 Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance Spectra of Lanthanum Complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1982, 1929–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J. Microhydration and the Enhanced Acidity of Free Radicals. Molecules 2018, 23, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutberlet, A.; Schwaab, G.; Birer, Ö.; Masia, M.; Kaczmarek, A.; Forbert, H.; Havenith, M.; Marx, D. Aggregation-Induced Dissociation of HCl(H2O)4 Below 1 K: The Smallest Droplet of Acid. Science 2009, 324, 1545–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hunter, J.P.; Dolezalova, S.; Ngwenya, B.T.; Morrison, C.A.; Love, J.B. Understanding the Recovery of Rare-Earth Elements by Ammonium Salts. Metals 2018, 8, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/met8060465

Hunter JP, Dolezalova S, Ngwenya BT, Morrison CA, Love JB. Understanding the Recovery of Rare-Earth Elements by Ammonium Salts. Metals. 2018; 8(6):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/met8060465

Chicago/Turabian StyleHunter, Jamie P., Sara Dolezalova, Bryne T. Ngwenya, Carole A. Morrison, and Jason B. Love. 2018. "Understanding the Recovery of Rare-Earth Elements by Ammonium Salts" Metals 8, no. 6: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/met8060465