The Structure of European Food Law

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. In Search of Structure

1.2. Structure

1.3. The ABC of EU Food Law

1.4. Overview

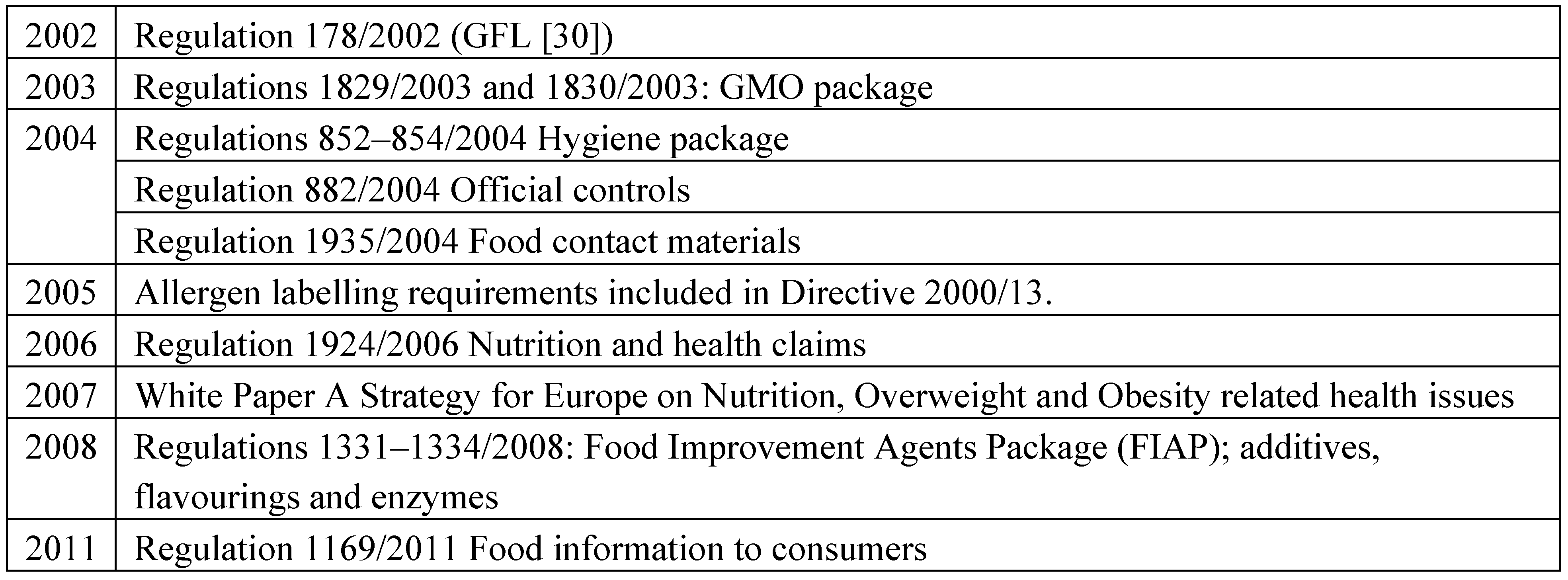

2. Development of EU Food Law

2.1. Introduction

2.2. Creating an Internal Market for Food in Europe

2.3. Advancement through Case Law

2.4. Breakdown

2.5. The White Paper: A New Vision on Food Law

2.6. EU Food Law in the 21st Century

3. General Concepts and Principles

3.1. Scope

‘Food’ (or ‘foodstuff’) means any substance or product, whether processed, partially processed or unprocessed, intended to be, or reasonably expected to be ingested by humans. ‘Food’ includes drink, chewing gum and any substance, including water, intentionally incorporated into the food during its manufacture, preparation or treatment. (…) ‘Food’ shall not include: (a) feed; (b) live animals unless they are prepared for placing on the market for human consumption33; (c) plants prior to harvesting; (d) medicinal products (…) (e) cosmetics (…) (f) tobacco and tobacco products (…) (g) narcotic or psychotropic substances within the meaning of the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, and the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971; (h) residues and contaminants.

3.2. Objectives

3.3. Principles

4. Product-Focused Provisions

4.1. Product Standards

4.2. Market Access Requirements

4.3. Food Safety Targets

5. Process-Focused Provisions

5.1. Processing

5.2. Trade

6. Presentation

6.1. Labelling

6.2. Nutrition and Health Claims

6.3. Protected Designations

7. Enforcement

7.1. Member States

7.2. Food and Veterinary Office

8. Incident Management

8.1. Communication

8.2. Role Businesses

8.3. Role Authorities

8.3.1. National Authorities

8.3.2. European Commission

- -

- suspend the placing on the market of the food/feed in question;

- -

- lay down special conditions for the food/feed in question;

- -

- adopt any other appropriate interim measure.

9. Liability and Consumers Rights

10. Science-Based Food Law

11. Conclusions and Discussion

References and Notes

- Wageningen University. “Master of Science specialisation Food Safety Law.” Available online: http://www.mfs.wur.nl/UK/orwww.LAW.wur.nl (accessed on 4 April 2013).

- Mary Ann Glendon, Michael W. Gordon, and Paolo G. Carozza. Comparative Legal Traditions. St. Paul: West Nutshell Series, 1999, pp. 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bernd M.J. van der Meulen, and Menno van der Velde. European Food Law Handbook. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2008, http://www.wageningenacademic.com/foodlaw.

- Jo H.M. Wijnands, Bernd M.J. van der Meulen, and Krijn J. Poppe, eds. Competitiveness of the European Food Industry. An Economic and Legal Assessment. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2007, http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/food/files/competitiveness_study_en.pdf.

- David Jukes. “University of Reading Food Law website.” Available online: www.foodlaw.rdg.ac.uk (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- Bernd M.J. van der Meulen, and Menno van der Velde. Food Safety Law in the European Union. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2004, European Institute for Food Law series, nr. 1; Available online: http://www.wageningenacademic.com/ (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- European Commission, Enterprise Directorate General. “Invitation to Tender No. ENTR/05/075 ‘Competitiveness Analysis of the European Food Industry’.” 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eurovoc. “Thesaurus of European Union Law in Eur-Lex.” Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/RECH_eurovoc.do (accessed on 10 April 2013).

- “European Council for Rural Law (CEDR: Comité Europeèn de Droit Rurale).” Available online: www.cedr.org (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- “European Food Law Association (EFLA).” Available online: www.efla-aeda.org (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- Ferdinanco Albisinni. “The Path to the European Food Law System.” In European Food Law. Edited by Luigi Costato, Ferdinanco Albisinni and Wolters Kluwer. Rome: Cedam, 2012, pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. White Paper on Food Safety. COM 719 final; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- “Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.” Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/JOHtml.do?uri=OJ:C:2008:115:SOM:en:HTML (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- “Treaty Establishing the European Community (EC Treaty).” Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2006:321E:0001:0331:EN:PDF (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- Morton P. Broberg. Transforming the European Community’s Regulation of Food Safety. Stockholm: SIEPS, 2008, pp. 17–23. http://www.sieps.se/en/publikationer/transforming-the-european-community%C2%B4s-regulation-of-food-safety20085.

- European Court of Justice. Case 120/78. “Rewe-Zentral AG v Bundesmonopolverwaltung für Branntwein [Cassis de Dijon].” 1979, ECR. 649–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ignacio Abaitua Borda, Rossanne M. Philen, Manuel Posada de la Paz, Agustín Gömez de la Cámara, Mercedes Diez Ruiz-Navarro, Olga Giménez Ribota, Jorge Alvargonzález Soldevilla, Benedetto Terracini, Serapio Severiano Peña, Carmen Fuentes Leal, and Edwin M. Kilbourne. “Toxic Oil Syndrome Mortality: The First Thirteen Years.” International Journal of Epidemiology 27 (1998): 1057–63. http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/27/6/1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emilio Gelpí, Manuel Posada de la Paz, Benedetto Terracini, Ignacio Abaitua, Agustín Gómez de la Cámara, Edwin M. Kilbourne, Carlos Lahoz, Bénoit Nemery, Rossanne M. Philen, Luis Soldevilla, and Stanislaw Tarkowski. “The Spanish Toxic Oil Syndrome Twenty Years after Its Onset: A Multidisciplinary Review of Scientific Knowledge.” Environmental Health Perspectives 110 (2002): 457–64. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1240833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig R. Whitney. “Food Scandal Adds to Belgium’s Image of Disarray.” New York Times. 9 June 1999. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F06E0DC1139F93AA35755C0A96F958260.

- James Graff. “One Sweet Mess.” Time. 21 July 2002. www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,322596,00.htm.

- BBC. “1990: Gummer Enlists Daughter in BSE Fight.” BBC. 16 May 1990. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/may/16/newsid_2913000/2913807.stm.

- European Parliament. “Temporary Committee of Inquiry into BSE.” OJ 1996 C 261/132. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. “Temporary Committee of Inquiry into BSE.” Report of the Temporary Committee of Inquiry into BSE, Set up by the Parliament in July 1996, on the Alleged Contraventions or Maladministration in the Implementation of Community Law in Relation to BSE, Without Prejudice to the Jurisdiction of the Community and the National Courts of 7 February 1997, A4–0020/97/A, PE 220.544/fin/A. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper on the General Principles of Food Law in the European Union, COM 176. 1997.

- European Commission. Communication on Consumer Health and Food Safety, COM (97) 183 final. 1997.

- European Court of Justice. Case C-157/96. The Queen vs. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and Commissioners of Customs & Excise, ex parte National Farmers’ Union and others, 1998, ECR I-02211.

- European Court of Justice. Case C-180/96 R. United Kingdom vs. Commission, 1996, ECR I-3903.

- European Court of Justice. Case C-209/96. United Kingdom vs. Commission, 1998, ECR I-5655.

- Nicole Coutrelis. “EU ‘New Approach’ Also for Food Law? ” In Food Law. Governing Food Chains Through Contract Law, Self-regulation, Private Standards, Audits and Certification Schemes. Edited by Bernd van der Meulen. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2011, pp. 381–90. www.wageningenacademic.com/eifl-06.

- Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety. OJ L 31/1, 1 February 2002.

- European Commission. White Paper on a Strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity Related Health Issues, COM 279. 1997.

- U.S. Congress. Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act; § 201 (21 USC § 321); 1938.

- Bernd van der Meulen. Reconciling Food Law to Competitiveness. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2009, http://www.wageningenacademic.com/reconciling.

- Bernd van der Meulen. “The Function of Food Law. On the Objectives of Food Law, Legitimate Factors and Interests Taken Into Account.” European Food and Feed Law Review 2 (2010): 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Anna Szajkowska. Regulating food law. Risk analysis and the Precautionary Principle as General Principles of EU Food Law. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2012, p. 155. http://www.wageningenacademic.com/eifl-07.

- Bernd van der Meulen. “The Global Arena of Food Law: Emerging Contours of a Meta-Framework.” Erasmus Law Review 3 (2010): 217–40. http://www.erasmuslawreview.nl/files/the_global_arena_of_food_law. [Google Scholar]

- Marsha A. Echols. Food Safety and the WTO: The Interplay of Culture, Science and Technology. The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto Alemanno. Trade in Food: Regulatory and Judicial Approaches in the EC and the WTO. London: Cameron May Ltd., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marco Bronckers, and Ravi Soopremanien. “The impact of WTO on European food regulation.” European Food and Feed Law Review 3 (2008): 361–75. [Google Scholar]

- Marielle D. Masson-Matthee. The Codex Alimentarius Commission and Its Standards: An Examination of the Legal Aspects of the Codex Alimentarius Commission. Den Haag: T.M.C. Asser Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joan Scott. The WTO Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures: A Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- D. John Shaw. Global Food and Agricultural Institutions. London: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peter van den Bossche, Nico Schrijver, and Gerrit Faber. Unilateral Measures Addressing non-Trade Concerns. Den Haag: Ministerie van BuZa, 2007, Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1021946 (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- Margaret Will, and Doris Guenther. Food Quality and Safety Standards, as Required by EU Law and the Private Industry with Special Reference to the MEDA Countries’ Exports of Fresh and Processed Fruits & Vegetables, Herbs & Spices A Practitioners’ Reference Book. Eschborn: GTZ, 2007, p. 162. http://www2.gtz.de/dokumente/bib/07-0800.pdf.

- Bernd van der Meulen. “The Core of Food Law. A Critical Reflection on the Single Most Important Provision in All of EU Food Law.” European Food and Feed Law Review 3 (2012): 117–25. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food additives. OJ L 354/16, 31 December 2008.

- Helle Tegner Anker, and Margaret Rosso Grossman. “Authorization of Genetically Modified Organisms: Precaution in US and EC Law.” European Food and Feed Law Review 1 (2009): 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs. OJ L 139/1, 30 April 2004.

- Regulation (EC) No 1830/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 concerning the traceability and labelling of genetically modified organisms and the traceability of food and feed products produced from genetically modified organisms and amending Directive 2001/18/EC. OJ L 268/24, 18 October 2003.

- Bernd M.J. van der Meulen, and Annelies A. Freriks. “‘Beastly Bureaucracy’ Animal Traceability, Identification and Labeling in EU Law.” American Journal of Food Law and Policy 2 (2006): 317–59. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004. OJ L 304/18, 22 November 2011.

- Dario Dongo. The Food Label. Ilfattoalimentare.it (e-book). 2011, p. 54. http://www.ilfattoalimentare.it.

- Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. OJ L 404/9, 30 December 2006.

- European Court of Justice. Case C-6/02. Commission vs. France, 2003, ECR I-2389.

- Council Regulation (EC) No 509/2006 of 20 March 2006 on agricultural products and foodstuffs as traditional specialities guaranteed, OJ L 93/1, 31 March 2006.

- Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 of 28 June 2007 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91. OJ L 189/1, 20 July 2007.

- Regulation (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on official controls performed to ensure the verification of compliance with feed and food law, animal health and animal welfare rules. OJ L 165/1, 28 May 2004.

- Council Directive 85/374/EEC of 25 July 1985 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning liability for defective products. OJ L 210, 7 August 1985.

- Bernd van der Meulen. “Science Based Food Law.” European Food and Feed Law Review 4 (2009): 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- “European Food Safety Authority.” Available online: http://www.efsa.europa.eu/ (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- Cécile Povel, and Bernd van der Meulen. “Scientific Substantiation of Health Claims—The Soft Core of the Claims Regulations.” European Food and Feed Law Review 2 (2007): 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bernd van der Meulen, Harry J. Bremmers, Jo H.M. Wijnands, and Krijn J. Poppe. “Structural Precaution: The Application of Premarket Approval Schemes in EU Food Legislation.” Food and Drug Law Journal 67 (2012): 453–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernd van der Meulen, ed. Private Food Law. Governing Food Chains through Contract Law, Self-Regulation, Private Standards, Audits and Certification Schemes. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2011, www.wageningenacademic.com/eifl-06.

- Klaus-Dieter Borchardt. The ABC of European Union Law. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Communities, 2010, p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- “Council of Europe.” Available online: http://www.coe.int/ (accessed on 2 April 2013).

- “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.” Available online: www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx (accessed on 10 April 2013).

- European Court of Justice. Case C-544/10. Deutsches Weintor eG v Land Rheinland-Pfalz, 2012, ECR I-0000.

- Bernd van der Meulen, and Eva van der Zee. “Through the Wine Gate: Case Note on Tentative First Steps in ECJ 6 September 2012 C-544/10 towards Human Rights Awareness in EU Food (Labelling) Law.” European Food and Feed Law Review 8 (2013): 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Otto Hospes, and Bernd van der Meulen. Fed up with the Right to food? The Netherlands’ Policies and Practices Regarding the Human Right to Adequate Food. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2009, http://www.wageningenacademic.com/righttofood.

- Edward M. Basile, and Melanie Gross. “The First Amendment and Federal Court Deference to the Food and Drug Administration: The Times They Are A-Changin’.” Food and Drug Law Journal 59 (2004): 31–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Annex 1

Basics of EU law

1. Introduction

2. Constitutional Framework

3. EU Legislation

4. Comitology

5. Agencies

6. Court of Justice

7. Member States

8. Human Rights Dimension

Annex 2

- -

- All EU legislation and case law is available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/en/index.htm;

- -

- Information on EU food law is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/food/;

- -

- For an elaborated account on EU food law see: Bernd van der Meulen and Menno van der Velde, European Food Law Handbook, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2008: http://www.wageningenacademic.com/foodlaw or Luigi Costato and Ferdinando Albisinni (eds.), European Food Law, Wolters Kluwer Italia, 2012;

- -

- The law journal specialised in EU food law is the European Food & Feed Law Review (EFFL): http://www.lexxion.eu/effl/. Every year EFFL organises a scientific conference;

- -

- Expertise on EU food law is available at the European Institute for Food Law: www.food-law.nl;

- -

- The association dealing with European Food Law, is the European Food Law Association (EFLA) http://www.efla-aeda.org/. Every second year EFLA organises a scientific conference.

- 1Bernd van der Meulen is Professor of Law and Governance at Wageningen University, the Netherlands. He is chairman of the Dutch Food Law Association (NVLR) and director of the European Institute for Food Law. An earlier version of this text has been published in Deakin Law Review in 2009 (volume 14, nr.2, p. 305–339). Comments are welcome at: [email protected]. Many thanks to Dominique Sinopoli for helping to improve the earlier version.

- 2Where reference is made to “we” this means the Law and Governance Group at Wageningen University. “I” is the author.

- 3The programme offers a choice of courses such as: Food Law; International and American Food Law; Food Law, Management and Economics; Food Quality Management; Basics in Food Technology; Food Safety Economics; Chinese Law on Food and Agriculture; Food Toxicology; Food Safety Management; Risks Associated with Foods; Intellectual Property Rights; Food, Nutrition and Human Rights and Risk Communication. For details see [1].

- 4In asking this question, we showed a civil law background. In an American booklet on comparative law [2], I found the following remark: “one of the greatest differences between legal education in common law and civil law systems appears in the manner in which the student is initiated into the study of law. While an American law student typically spends the first days of law school reading cases and having his or her attention directed over and over again to their precise facts, a student of the civil law is provided at the outset with a systematic overview of the framework of the entire legal system. The introductory text (a treatise, not a casebook) may even include a diagram depicting ‘The Law’ as a tree, with its two great divisions, public and private, branching off into all their many subdivisions and categories—each of which will become, in turn, the subject of later study.” Systematisation is not limited to education: “all other actors in the legal system receive their training from the scholars who transmit to them a comprehensive and highly-ordered model of the system that to a great extent controls how they organise their knowledge, pose their questions and communicate with each other. This model is not only taught in the universities but constitutes the latent framework of the treatises and articles produced by the professors. Furthermore, legal periodicals, which in civil law countries are run by professors rather than students, play a much more important role there than in common law countries in bringing new legislation and court opinions to the attention of the profession” ([2], p. 91). Such a diagram can indeed be found in ([3], pp. 50–51).

- 6In our experience, food regulatory affairs managers in particular feel more confident for better understanding the context of the rules they work with on a daily basis.

- 7How does one establish the measure of regulation of a sector? According to [7], food is the third most regulated sector in the EU. If we simply count hits in the EU database of official publications [8], with 14,569 (out of 68,735 for the category Agri-Foodstuffs) foodstuffs is first in front of sectors such as chemistry with 8,330 (out of 38,465 for industry) (visited 10-3-2013).

- 8We include legislation on the premises under this heading. In the future this may develop into a separate category. This topic is not addressed in this contribution.

- 10On the history of EU food law, see also [11].

- 11In different stages of its development, it is also referred to as the “common market” or the “single market.” The expressions are used interchangeably in this article.

- 12The distinction between horizontal and vertical directives will be discussed hereafter.

- 13Commission White Papers traditionally contain proposals for Community action in specific areas, and are developed in order to launch consultation processes at the European level. If White Papers are favourably received by the Council, they often form the basis of later “Action Programs” to implement their recommendations.

- 15Vertical legislation resembles the product standards of the Codex Alimentarius and standards of identity in US food law.

- 16E.g. sugar, honey, fruit juices, milk, spreadable fats, jams, jellies, marmalade, chestnut puree, coffee, chocolate, natural mineral waters, minced meat, eggs, fish. Wine legislation is a body of law in itself.

- 17Previously Article 28 of the EC Treaty [14], at that time numbered Article 30.

- 20This will be shown later on in this article. In the meantime, the protection of consumer safety has been concentrated at EU level.

- 21See [17,18] on finding that the toxic oil syndrome (TOS) epidemic that occurred in Spain in the spring of 1981 caused approximately 20,000 cases of a new illness. Researchers identified 1,663 deaths between 1 May 1981 and 31 December 1994 among 19,754 TOS cohort members. Mortality was highest during 1981. The poisoning was caused by fraud consisting of mixing vehicle oil with consumption oil.

- 22One example is the Belgian dioxin crises. It was caused by industry oil that had found its way into animal feed and subsequently into the food chain [19]. Another example is the introduction of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) into pig feed in 2002 [20]. Sugar discharges from the production of MPA, a hormone used in contraceptive and hormone replacement pills, were used in pigs feed and, by that route, MPA entered the food chain. In 2004, a dioxin crisis broke out in the Netherlands.

- 23Including foot-and-mouth disease, SARS, pig plague and avian influenza.

- 24Such as the melamine crisis.

- 25Symbolic became the TV footage where the responsible Secretary of State, John Gummer is shown feeding his little daughter a hamburger, to convince the public that nothing was wrong with British beef [21].

- 26The Green Paper in turn referred to the Sutherland Report of October 1992: “The Internal Market after 1992; Meeting the Challenge.” It is, however, beyond the scope of this article to trace the history of EU food law in all its rich detail.

- 27Unlike a Green Paper that is intended mostly as a basis for public discussion, a White Paper contains concrete policy intentions.

- 28This heralded in food an emphasis on regulatory involvement in the market that contrasts with the so-called “new approach” that was generally followed with regard to product standards. In this new approach, EU legislation limited itself to setting the safety requirements, leaving elaboration in technical standards to the private sector. For more on this topic, see [29].

- 29In the White Paper, the Commission speaks of a European Food Authority. The word “safety” was inserted later.

- 30Contemporary European food law displays several characteristics in which it is different from its predecessor: more emphasis on horizontal regulations (than on vertical legislation); more emphasis on regulations that formulate the goals that have to be achieved, the so-called “objective regulations,” than on means regulations; increased use of regulations (rather than directives) and thus increasing centralisation.

- 31Unlike in food safety law where responsibility rests with food business operators, according to the White Paper on A Strategy for Europe on Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity related health issues [31], ultimate responsibility for one’s lifestyle and that of one’s children is on the individual.

- 32Surprisingly, although the European legislature had been very active in the field of food law, the term “food” was for the first time defined in the 2002 General Food Law. The GFL does not distinguish between food and food ingredients as some older legislation does. Ingredients fulfil the definition of food and are (therefore) subject to the same safety rules. Only in labelling legislation does the distinction still have significance.

- 33Such as oysters (footnote added).

- 35For an overview of international food law, see: Bernd van der Meulen “The Global Arena of Food Law: Emerging Contours of a Meta-Framework” [36]. On international food law and related topics see also: Marsha A. Echols [37], A. Alemanno [38], Marco Bronckers and Ravi Soopremanien [39], Marielle D. Masson-Matthee [40], Joan Scott [41], D. John Shaw [42] and G. Faber, Unilateral Measures Addressing non-Trade Concerns [43].

- 36These quality requirements are increasingly abolished.

- 37While I am writing this line, a radio commercial makes fun of this legislation by stating that it would be illegal to call their product a “jam” because it has less than 60% sugar. The hope is expressed that they will not be prosecuted for being too healthy.

- 38Article 3(2) (a) Regulation 1333/2008 on food additives. Note that this concept of food additives is much less wide than the one applied in the USA. See Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act § 201 (21 USC § 321).

- 39See, for example, Framework regulation 315/93; Regulation 1881/2006 on mycotoxins and chemicals; Regulation 2073/2005 on microbiological criteria; Regulation 396/2005 on pesticide residues; Regulation 470/2009 and Regulation 37/2010 on veterinary drugs, Directive 96/22 on hormones, Regulation (EURATOM) 3954/87 and Regulation (EURATOM) 944/89 on radioactive contamination.

- 40At least in public law an exception applies. Primary producers following private standards such as GlobalGAP have to implement HACCP.

- 41This regulation replaces the General Labelling Directive 2000/13 and some other horizontal pieces of legislation on labelling. The idea is to streamline food labelling law in the EU. For an eBook commenting on and explaining this regulation, see The Food Label [52].

- 42This is the most concrete achievement to date in translating nutrition and health policy to legislation.

- 43In the EU, for products with reduced energy, the expression “light” is preferred over the expression “diet” because the latter is associated with illness.

- 44This is the case in literature and common speech, not in legislation.

- 45European Court of Justice. Case C-6/02. Commission vs. France [49]: protected designations of origin may not be introduced by national legislation but may only be afforded within the framework of Regulation (EC) 2081/92 (now Regulation (EC) 510/2006).

- 46The so-called subsidiarity principle applies. If action by the Member State(s) can solve the problem, the European Commission should not become involved.

- 47For the latest example (at the time of writing), see Regulation 1169/2011 on food information to consumers.

- 48As amended by Directive 1999/34.

- 50Intermediately it was labelled: European Communities and European Community. Each new name designated a further step in the integration process.

- 51For a very accessible introduction to the system of EU law freely available on the Internet, see: The ABC of European Union law [64].

- 57See Articles 289, 290 and 291 TFEU [13] and Regulation 182/2011.

- 58Article 58 Regulation 178/2002 (GFL [30]).

- 59See 7.2 above.

- 60See chapter 10 above.

- 61Depending on the type of risk management measure the responsibility may also rest with the Member States or with the Council and the European Parliament jointly with the Commission.

- 62See Article 19(3) TEU.

- 63With the notable exception of competition law (anti-trust law).

- 64This is an international organisation distinct from the EU. It should in particular not be confused with the Council which is an Institution of the European Union. On the Council of Europe, see: [65].

- 65In a ruling of 6 September 2012 (Case C-544/10 Weintor) [67] the European Court of Justice for the first time judged a provision of food law against the Charter of fundamental rights of the European Union. It upheld the ban on health claims on alcoholic beverages. On this ruling, see: “Through the Wine Gate: Case note on tentative first steps in ECJ 6 September 2012 C-544/10 towards Human Rights awareness in EU food (labelling) law” [68].

- 66For a discussion of a similar lack in human rights consciousness in one of the EU Member States, see: Fed up with the right to food? The Netherlands’ policies and practices regarding the human right to adequate food [69].

- 67Unlike US food law, where labelling legislation is scrutinised in the context of the First Amendment. See for example: “The First Amendment and Federal Court Deference to the Food and Drug Administration: The Times They Are A-Changin’” [70].

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Van der Meulen, B.M.J. The Structure of European Food Law. Laws 2013, 2, 69-98. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws2020069

Van der Meulen BMJ. The Structure of European Food Law. Laws. 2013; 2(2):69-98. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws2020069

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan der Meulen, Bernd M.J. 2013. "The Structure of European Food Law" Laws 2, no. 2: 69-98. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws2020069

APA StyleVan der Meulen, B. M. J. (2013). The Structure of European Food Law. Laws, 2(2), 69-98. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws2020069