Abstract

The Western ‘discovery’ of Japanese cinema in the 1950s prompted scholars to articulate essentialist visions understanding its singularities as a result of its isolation from the rest of the world and its close links to local aesthetic and philosophical traditions. Recent approaches however, have evidenced the limitations of this paradigm of ‘national cinema’. Higson (1989) opened a critical discussion on the existing consumption, text and production-based approaches to this concept. This article draws on Higson´s contribution and calls into question traditional theorising of Japanese film as a national cinema. Contradictions are illustrated by assessing the other side of the ‘discovery’ of Japanese cinema: certain gendaigeki works that succeeded at the domestic box office while jidaigeki burst into European film festivals. The Taiyōzoku and subsequent Mukokuseki Action films created a new postwar iconography by adapting codes of representation from Hollywood youth and western films. This article does not attempt to deny the uniqueness of this film culture, but rather seeks to highlight the need to reformulate the paradigm of national cinema in the Japanese case, and illustrate the sense in which it was created from outside, failing to recognise its reach transnational intertextuality.

1. Introduction

Since the postwar discovery of Japanese cinema in Western Europe and the U.S., there has been a tendency to define it as an example of national cinema through essentialist visions, understanding its uniqueness as a result of its isolation from the rest of the world. There are two methods for establishing a coherent imaginary of national cinema: First, looking outward, beyond its borders, comparing it to other cinemas, highlighting its difference and considering it in terms of its degrees of otherness. This approach was generally applied in terms of opposition to Hollywood in order to assess how ‘national cinema’ challenges the institutional mode of representation.1 This was the approach that dominated scholarly works until the 1980s; trying to create a sense of national ‘identity’ through films. The second is carried out through an inward-looking kind of introspective analysis of this cinematic culture, exploring the circumstances of production. National cinema is assessed in relation to its local aesthetic and philosophical traditions, and authors interrogate how and if it reflects the nation itself and mirrors its cultural heritage. This academic stream tends to focus on films as an unequivocal result of the context in which they are made.2

However, cinema has been international since its inception, and assessing these cultural products, either as a result of a creative or an industrial process, within the boundaries of their national borders, is always controversial. This problem has become more evident in recent years. In an increasingly interconnected world, scholars have pinned down the limitations of earlier approaches and are proposing new methodologies that are calling into question the paradigm of ‘National Cinema’. This theoretical framework is grounded on an unstable concept: what are we talking about when we talk about national cinema? Is it the group of films produced by a local film industry? Are they those films watched within a domestic market? Do these films represent the culture of a nation? While Japanese cinema in general may fit within the different approaches to ‘national cinema’, this article seeks to demonstrate how all of them have significant inconsistencies, unless theoretical methodologies are reformulated through the incorporation of a transnational dimension.

In the late 1980s, Higson (1989) opened an enriching discussion posing essential questions to start dealing critically with the paradigm of National Cinema, noting that there is no universally accepted discourse for defining this concept. This idea started to be used in the context of the growing awareness of the auteur figure from the late 1950s that seemed to lead those New Waves in several parts of the world articulating an alternative to Hollywood. This criticism-led approach described by Higson could be regarded as one reducing national cinemas to arthouse, modernist, avant-garde, and quality films. It became useful for critics to describe film movements such as German Expressionism, French Surrealism, Italian Neorealism or Japanese Nūberubāgu. Stephen Crofts also adopted this approach, stating that the true national cinema is the one that resists or ignores the institutional mode of representation (Crofts 1993, pp. 49–67). However, this method presents a twofold inconsistency: First, it neglects the fact that key films and filmmakers often used as representatives of certain national cinemas do not necessarily reject Hollywood patterns of representation. For example, Mizuguchi and Ozu developed their singular ‘classic style’ only after adopting significant Hollywood practices. Second, contributions from cultural studies (Bourdieu 1993, pp. 29–74) have helped film theorists to understand that the differences between author cinema linked to high culture and commercial cinema related to popular culture are blurred.

The author who categorically defended the specificity of Japanese cinema as a National Cinema, Noël Burch, explains in his well-known work To the Distant Observer that this film corpus is the result of a cultural practice emerging from a tradition that challenges Western patterns of representation (Burch 1979, pp. 67–74). Burch noted that Japanese filmmakers did not follow Western cannons, and instead, seemed to evolve from their own cultural referents. Thus, this work proposed a ´turn to the Orient’ that consisted of interrogating those aesthetic and philosophical developments that differed from those evolved in the West, a methodology also applied by Bordwell and Thomson (1976).3 They were major contributions, since they highlighted the value of Japanese cinema as opposed to those critics who lamented its apparent delay in adapting Western narrative codes, although these ideas also brought some paradoxes, such as describing Ozu and Mizoguchi’s classicism as modernist because it did not fit within Western aesthetic and narrative development. Burch´s work, in line with other influential works, such as that of Roland Barthes (1984), was also key to defying the Eurocentrism pervading Western studies in Japan because it analysed its cultural products in close relation to the context of their creation. This was crucial for overcoming the initial analysis of Japanese films as dominated by a feeling of estrangement experienced by ´distant observers’. However, theories on Japanese film should be developed without neglecting interactions between the local and the global, as Burch himself noted:

There is an awkward problem which the observer of Japanese things must confront. It is one to which we have already alluded in its ideological formulation: the uniquely Japanese faculty for assimilating and transforming elements ‘borrowed’ from foreign cultures. To my knowledge, no substantial effort has yet been made in the West to define or analyse this phenomenon, though it has often been commented upon(Burch 1979, p. 89).

Burch suggests that studying the coexistence of ‘foreign influence’ and ‘Japanese uniqueness’ by putting them into dialogue might be an enriching method to assess the nature of Japanese films in depth. Although this point was never developed in his book, Burch opens interesting possibilities for studying Japanese specificity from its singular adaptation of Western codes.

2. The ‘Kimono Effect’

Higson identifies another interesting approach to national cinema; a ‘consumption-based’ definition in which the major concern is which films audiences watch (1989: 39). However, this perspective presents important contradictions, as the paradigm of ‘national cinema’ is sometimes grounded in films that are mainly watched abroad. Thomas Elsaesser (1989) already addressed this problem from the European context, showing that New German Cinema was more coherent outside than inside Germany, where it only reached 8% of the audience. Aspects of this national history were well received by foreign audiences—such as Nazism and war topics—, while domestic audiences preferred socially concerned films on topics like feminism, regionalism, and oppressed minorities, which were covered by television reportages in other countries.

Similarly, the idea of Japanese Cinema as a National Cinema started to be articulated in the postwar period through films that were being exported overseas. Therefore, the contradiction presented by Elsaesser is extremely useful for assessing how the theorising of Japanese National Cinema was articulated from the ‘Western discovery’ of Japanese films during the burst in European film festivals in the 1950s. This phenomenon started with Akira Kurosawa’s Rashōmon winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and an Academy Award in 1951. The same year, Kōzaburō Yoshimura’s The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) was nominated in Cannes and won the prize for the best cinematography in Venice. The following year marked the discovery of another early master, Kenji Mizoguchi, who received several prizes in Venice: the Golden Lion for The Life of Oharu (Saikaku ichidai onna, 1952), Silver Lion for Tales of Ugetsu (Ugetsu monogatari, 1953) and the same prize for Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshō dayū, 1954). Mizoguchi also obtained three nominations for Best Film; one in Cannes for The Crucified Lovers (Chikamatsu monogatari, 1955) and two in Venice for Princess Yang Kwei-Fei (Yokihi, 1955) and Street of Shame (Akasenchitai, 1956). Kurosawa returned to Venice with The Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai, in 1954), which won the Silver Lion and also two Oscar nominations. Teinosuke Kinugasa, who had presented his avant-garde film Crossways (Jūjiro, 1928) in Europe in the late-1920s, received the Grand Prize award at the Cannes Film Festival and two Oscars for Gate of Hell (Jigokumon in 1953). In 1958, Tadashi Imai obtained the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival with The Rickshaw Man (Muhomatsu no issho, 1958), while Eisuke Takizawa obtained a nomination for The Temptress and the Monk (Byakuya no Yōjo, 1958).

The success of Rashōmon and Gate of Hell in the Academy Awards also triggered a growing interest in Japanese films among the American audience. The American Annual Variety’s Film Review included comments on Keigo Kimura’s Beauty and the Thieves (Bijo to Tōzoku, 1952), a version of a Kabuki play set in the 11th century, and Noboru Nakamura’s Adventure of Natsuko (Natsuko no bōken, 1953), an adaptation of a Yukio Mishima novel.4 Another film set in the Japanese legendary past was Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai (1954), which obtained an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1955.5

However, Giuglaris and Giuglaris (1957), who were film critics working in Japan in the 1950s, point out a paradoxical fact: the films just mentioned, which were receiving awards in the West, were being substantially unsuccessful in Japan. Even if Rashōmon received two awards in Japan and was listed as the 5th best film of 1950, most of the Japanese critics disliked the film as it was regarded as a bombastic, incomprehensible, and unrealistic work by Japanese critics. It was not even considered a B Grade film (1957: 27). Months after winning the Golden Lion in Venice, it was released again in Japan and the Giuglares witnessed Japanese audience’s disappointment after the screening. Their book includes quotations from viewers showing their incredulity saying that they could not believe that this film had been granted an award by a foreign jury. Something similar happened with The Gate of Hell, which was not even included in the best 10 of that year. In fact, four months after its success in Cannes, it was a resounding failure at the Japanese box office.

What sort of mysterious phenomenon was taking place, according to which unnoticed films in Japan were becoming so successful in the West? After a brief overview of the Japanese films that had triumphed in Europe and the U.S., one common element seems clear: all of them were jidaigeki or ‘period films’ and presented a legendary Japan stuck in its traditional culture. While jidaigeki seems to have fascinated Western spectators, this genre had been particularly promoted alongside the rise of militarism from the 1930s and presumably Japanese audiences were no longer attracted by this theme in the postwar period. Also, David Bordwell (1994) proposed another hypothesis; that these films projected such a high exoticism that not even the Japanese could identify with it.

Nevertheless, this did not happen by chance; it was a consequence of a policy deliberately designed by Japanese Studios aimed at astonishing foreign audiences with exotic images of a distant country. Therefore, they promoted what Antonio Weinrichter (2002) coined the ‘kimono effect’; the astonishment of Western audiences by the exoticism projected in Japanese films. As a consequence, it cannot be said that works screened at European festivals were in accordance with the general taste in Japan. To a great extent, films distributed in Europe and the U.S. belonged to Daiei productions. Unlike the other big five studios of the 1950s, Daiei had no distribution network and barely owned theatres for exhibition. The latter, particularly, had no choice but to develop a policy oriented towards foreign exportation. As the president of Daiei, Masaichi Nagata, acknowledged:

The ideal solution to Japanese Cinema is conquering the American market. That’s not an easy task. Experience has shown us that European films have never made much of an impact [on the] North American market. That must be taken into account. We carefully studied international markets and then we noticed that the weak point was in the European countries. It was then that we decided to launch historical, traditional, exotic films to be submitted in their festivals, mainly Venice and Cannes.(Giuglaris and Giuglaris 1957, p. 32. My translation)

This question makes theorising Japanese cinema highly problematic, as it was based on a fragmented view of its film heritage which had been cherry-picked to astonish audiences in the West. This brings to the fore how, ironically, the idea of national cinema ended up being constructed from the outside. In this sense, Kikuo Yamamoto (1983 p. 629) pointed out that it was the American critic Donald Richie (1974) who first named Ozu as the ‘most Japanese’ of Japanese directors. It is important to note that this imaginary was created ignoring the complexity of transcultural interactions. For example, Isolde Standish noted that while Ozu’s evocation of the ‘ephemeral’ has been linked to the notion of mono no aware (‘pathos of things’) of the Heian period in the ninth century, it is in fact a modern reappropriation resulting from the new ways of fragmenting and reordering the world brought by the cinematic technology imported from the West at the turn of the twentieth century (Standish 2012, p. 6). Yamamoto (1983) had opened the possibility of analysing the mutual influence of East and West on each other’s films, which can be traced back even among the filmmakers that had been chosen to epitomize the uniqueness of Japanese cinema. In fact, the most outstanding works by Kurosawa were inspired by moral and philosophical conflicts depicted in Western literature: his Ran (1985) was an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s “King Lear”, Throne of Blood (1957) was a film version of “Macbeth”; Leo Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” inspired his Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurái, 1954) is a loose adaptation going back to the Ancient Greek play “Seven Against Thebes” by Aeschylus.

In addition, Mizoguchi became one of the main representatives of Japanese cinematographic classicism alongside Yasujirō Ozu. However, we should not forget that in the 1920s Ozu and Mizoguchi belonged to a group of filmmakers seeking to modernise cinema by adapting Western modes of representation. Foreign filmmakers such as Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg and Erich von Stroheim had a significant impact on them as their films were imported to cover the lack of new releases after the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923. For instance, Ozu and Mizoguchi opposed the use of onnagata, men playing female roles, inherited from the tradition of Kabuki theatre and also rejected the use of benshi, narrators during the screenings. Benshi invented dialogues and interpreted films according to their will in order to fix meanings and avoid manipulations, both filmmakers added intertitles, which was a clear sign of Western influence during the silent era.

3. Imagining a ‘Nation’

There is another way to address the issue of National Cinema, which Higson defines as the ‘text-based’ approach, focusing on narrative and aesthetic aspects (1989: 43). This methodology can be developed in two directions. One would be grouping films that share a common style or formal systems of representation that work as an allegory of a national culture. However, this tendency was based on a structural problem: understanding Japanese cinema as if it were a unified text, ignoring the plurality of narrative patterns and historical stages. This approach was already called into question by Audie Bock (1978), who tried to categorise distinctive periods in the history of Japanese Cinema as ‘Early Masters’, ‘Postwar Humanists’ and the ‘New Wave’. One decade later, David Desser (1988) confirmed the distinction, while introducing the concept of ‘dominant paradigms’ rather than historical periods, given that classical Early Masters’ Classicism, Modern Postwar Humanism and Modernist New Wave were simultaneous during certain periods of time.

Another direction that the text-based approach may take is gathering those films projecting an alleged idea of a Nation. These studies explore to what extent cinema is engaged in constructing a sort of national identity. The main weakness of this method is mistakenly considering that national cinema has provided unproblematised imagery of nationhood, neglecting any ethnic, social, cultural, or sexual diversity. The 19th-century definitions of a nation based on communities apparently sharing a certain language, religion, and folkways have been called into question by recent approaches. As Anthony Giddens (1990, p. 65) argues, the creation of a ‘national identity’ is one of the consequences of modernity as we see increasing pressure for erasing regional cultural diversity to strengthening boundaries within the national borders. To articulate a bounded geo-political entity it was necessary to facilitate, in Anderson Benedict’s terms, the ‘re-imagining of communities’ as factitious entities that would fit in the idea of the modern nation-state (Anderson 1991, pp. 204–6).

Cinema played a major role in the dissemination of these national entities. However, while some films may be seen as a result of a millenary philological and aesthetic tradition, others can only be explained by calling this tradition into question. In other words, some films are precisely made as a response to rather than as a result of their cultural background. For example, some authors transgress normative sexuality, such as Toshio Matsumoto’s representation of transexuality in Funeral Parade of Roses (Bara no Sōretsu, 1969) and Nagisha Oshima’s challenge to heteronormative gender roles pervading samurai films with the depiction of homosexual love in Taboo (Gohato 1999). Other works have challenged the idea of ‘Japaneseness’ from an undefined space that hardly fits within the paradigm of national cinema. For instance, I have written elsewhere on the representation of the minority of Ainu people by foreign authors in works mainly aimed at the Western audience, such as the early Lumière brothers’ actualités, Benjamin Brodsky´s travelogues (Centeno Martín 2017) and Neil Gordon Munro´s ethnographic documentaries (Centeno Martín 2018). Other examples may be found in films made by Zainichi about Korean residents living in Japan such as Yang Young-Hee’s Dear Pyongyang (2006). Not less important are the critical voices raising contradictions regarding the continuity of the Imperial Household in the postwar democracy. Fumio Kamei attacked the tennō sei (‘Emperor system’) that had been used to legitimise the authority of the Emperor from Meiji Restoration by addressing the question of responsibility in World War II in The Japanese Tragedy (Nihon no higeki, 1946). Along the lines, the taboos related to war responsibility and the atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese Imperial Army are tackled by Kazuo Hara in The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (Yuki Yukite Shingun, 1987). Additionally, hegemonic discourses of the nation are challenged by films such as The Insect Woman (Nippon Konchūki, 1963) and History of Postwar Japan as Told by a Bar Hostess (Nippon Sengoshi—Madamu onboro no Seikatsu, 1970), in which Shōhei Imamura rejects the hegemonic discourses on the history of postwar Japan as told from the male elites of the country and instead decides to narrate it from the point of view of female outcasts who are prostitutes or burakumin—cast of the untouchables.

In his criticism of seeing films as a mirror of a nation, Higson noted that while the paradigm of National Cinema may be helpful for labeling films, it is a dangerous tautology that necessarily fails to reflect the diversity of every society (2000: 63–74). Film representations of a nation draw on an ‘imagined community’ which is often demarcated in a limited geographical space inhabited by an apparent unified people. This ideological construction has perpetuated an artificial imagination alongside nationalist discourses that always try to repress the complexity that shapes every society. Thus, films tend to project a homogeneous community which needs to be coherent with stereotypes, national myths and what is considered part of the traditional culture, therefore articulating an image that is too simplistic and, as a consequence, necessarily wrong. A more comprehensive approach to national cinema should take into account those examples presenting resistance to predominant discourses and including these stories of crisis and negotiation of the idea of nation.

Higson (2000) proposes that films on and made by Diasporas revisit the idea of ‘community’ and he uses them to maintain that national categorizations should be replaced with a transnational perspective. This proves to be a helpful epistemological tool to determine how cinematic productions are unavoidably hybrid cultural forms. From the early 2000s, the global world and the increasingly international production and circulation of films have prompted scholars to seek new theoretical frameworks along these lines. Mette Hjort (2010, pp. 12–33) expands the transnational, claiming that it must be applied to wider aspects of production, distribution, and reception. She provides a useful typology of ‘cinematic transnationalism’ to assess contemporary film phenomena. Simultaneously, Higbee and Song (2010, pp. 7–21) advocate new approaches for the study of East Asian cinemas by incorporating a ‘critical transnationalism’ in film studies. Toby Miller (2001) marked a departure from earlier paradigms, using World Cinemas as a rubric, with strong intellectual allegiances to Area Studies, collectively grouping films from non-Western geographies. Harootunian and Miyoshi (2002) argued that Area Studies in general had collapsed in the 1990s, stating that the fall of the Berlin Wall triggered the end of geographical locations as sufficient criteria in themselves for academic research. This marked the emergence of ‘Global Cinema’ Studies in the 21st century. These contributions have also been essential to overcoming the difficulties of defining ‘national cinema’ in economic terms (Higson 1989, p. 38), establishing a correspondence with its domestic film industry. In recent years, key figures of the cinematographic scene in Japan would fall out of this category. For example, Takeshi Kitano’s Brother (2000) is a U.S.–Japan coproduction; Hideo Nakata’s The Ring 2 (2005) was made in the U.S.; Shunji Iwai’s Vampire in Canada; and Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away was distributed worldwide by Walt Disney Pictures.

4. Cultural Products beyond National Boundaries

Despite its contradictions, this text-based approach has triggered a long discussion since the influential Siegfried Kracauer (1947) proposed a study of cinema as a cultural expression of a nation. Through his analysis of Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Kracauer claimed that the film anticipated the rise of Nazism in Germany and explained how films can project the anxieties, fears, and daydreams of a society in which they are made. Soon after that, Georges Sadoul (1966) revitalised this tendency, stating that nation and people are the material on which a great number of films are based. More recently, a semiotic approach prompted by Stephen Prince and Philip Rosen has linked cinema to a national culture through a ‘culturalism’ in film studies that is described by David Bordwell (1996). These authors discuss the necessity of studying where and when cultural parameters produce meaning on cinematographic images. Prince claims that every discourse, either linguistic or cinematographic, is culturally set, and as a result, concludes that systems of signs do not produce meaning outside a cultural and social context (Prince 1991, p. XV).6 Rosen takes Kristeva’s notion of intertextuality to delimit national cinema as a coherent corpus of films that produce certain insight into a given local culture (Rosen 1984, pp. 17–28). To form a national cinema, it would be necessary for a given nation to have a sound film production, with enough historical weight to be able to create its own cinematic macro-discourse. Thus, the existence of a national cinema would depend on the consistency of a shared imaginary and its own referential universe.

Japanese cinema has often been used as a quintessential example of this theoretical perspective, seeking to justify how it is built on a self-referential universe, dominated by singular narrative and aesthetic conventions. However, this approach presents a structural limitation, only tackling film works from within national borders and neglecting transnational phenomena of a different kind that can be found in film production, distribution, or consumption. Prince ignored that filmmakers’ sources of inspiration may be found far from the geographical and cultural context in which films are made. Rosen also reduced the imaginary of a national cinema to local references, a limiting view that does not take into account a wider intertextuality beyond national borders.

5. Transculturality in the Domestic Market

In the case of Japanese cinema, its transnational intertextuality was initially obscured by the first views relying on those period dramas that were selected to be exported to the West in the 1950s. However, as we have already seen, they were not particularly successful in the domestic market. How would the theorising of Japanese cinema have changed if it had been founded on those films that were popular in Japan? The following table is quite illustrative for thinking about the kinds of nuances and new questions that would have been added to the paradigm of national cinema.

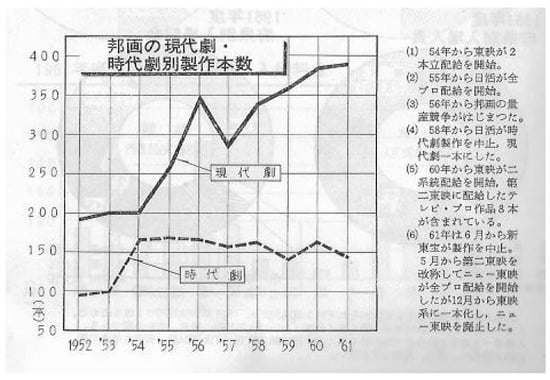

As we can see, jidaigeki films were far from the trendy genre of that time and their production was greatly below that of gendaigeki or ‘contemporary dramas’ (see Figure 1). While Western audiences were astonished by exotic images of a feudal Japan of geisha and samurai during the internationalisation of this cinema in the 1950s, the Japanese crowd was fascinated by a different kind of exoticism; the predominance of American popular culture in the new youth cinema (seishun eiga) released at the time. This genre had originally been created by American International Pictures, which discovered the teenage market in the early 1950s. The demography of postwar audience had changed both in the U.S. and Japan. By the mid-1950s, the generation of baby boomers had become a new market for the culture industry. Although at the beginning of the decade Daiei Studios had already started creating contents for the teenage (jūdai) audience, the problem of youth became predominant from the release of taiyōzoku films. Nikkatsu, which stopped the production of jidaigeki films in 1958, engaged in the production of films for this new niche market with the taiyōzoku, which literarily means ‘Tribe of the Sun’, a group of films released in the summer of 1956.

Figure 1.

Production of gendaigeki (contemporary dramas) (continuous line), and jidaigeki (period dramas) (discontinuous line), between 1952 and 1961. Source: Vv. Aa. 1963. Eiga nenkan. Tokyo: Jijitsūshinsha, p. 36.

The first one, Takumi Furukawa’s Season of the Sun (Taiyō no kisetsu, 1956), is based on Shintarō Ishihara’s eponym short novel, published the previous year. The film provided a form of escapism portraying the bourgeois lives of university youngsters from high-class families living in posh residential areas along the Shōnan Coast. After its success, Daiei tried to take advantage of this phenomenon with the adaptation of another novel by Shintarō Ishihara, Punishment Room (Shokei no heya), directed by Kon Ichikawa and released in June. Additionally, Nikkatsu hurried to make its second film, Kō Nakahira’s Crazed Fruit (Kuruta Kajitsu), which was released in July and made Yūjirō Ishihara an icon of Japanese popular culture at the time. In August, this company released Takumi Furukawa’s Backlight (Gyakkōsen), an adaptation of a novel by the female writer of youth literature, Kunie Iwahashi. Eventually, Tōhō also joined the taiyōzoku phenomenon with the production of Hiromichi Horikawa’s Summer in Eclipse (Nisshoku no natsu), released in September and starring Shintarō Ishihara himself, whose Western looks and hairstyle made a great impact among the young audience. The Californian look of taiyōzoku characters, with sun glasses, baggy trousers and Hawaiian shirts was reminiscent of Marlon Brando’s style in The Wild One (László Benedek, 1953) and James Dean’s in Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955).7 These films were aimed at a new generation who had left behind the hardships of the immediate postwar and was increasingly exposed to the iconography and values projected by the American popular culture. Thus, these youth icons were often featured on screen driving convertible cars and engaging in new forms of entertainment, such as sailboats, water skiing, boxing, and jazz clubs. Critics of the time complained that the portrayal of youth in novels and films was not a faithful representation of its social reality (Endō 1955, p. 118; Mashita 1956, pp. 88–98; Nakaya 1956, pp. 21–24; Takeuchi 2003, p. 80). More recently, scholars have interrogated how these characters created a transcultural iconicity that somewhat conveyed the anxieties, daydreams, inferiority complexes, and aspirations of the postwar youth (Galbraith and Dundan 2009; Schilling 2007; Raine 2000; Centeno Martín 2016).

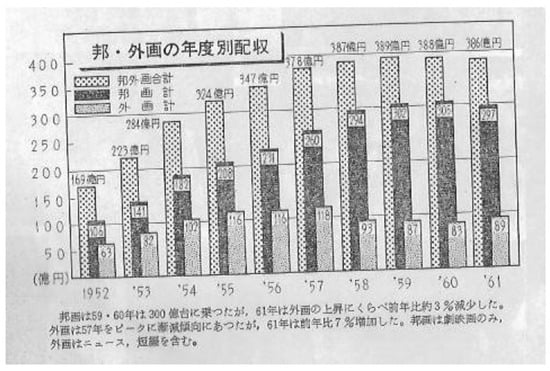

While the jidaigeki films leading the ‘kimono effect’ in the West were a failure in Japan, these taiyōzoku films obtained great success at the box office. The three Nikkatsu films, Season of the Sun, Crazed Fruit and Backlight raised ¥500 million; Punishment Room and Summer in Eclipse made around ¥150 million each (Namba 2004, p. 165). Media pressure exerted by the American stars must have been especially intense between 1952 and 1957, a period in which the distribution of foreign films in Japan doubled, rising from 63 to 118 (Vv. Aa. 1963, 35), and the assimilation of these Hollywood codes continued in the films including a juvenile star system created by Nikkatsu in the following years featuring: Yūjirō Ishihara, Akira Kobayashi, KeiichirōAkagi, Kōji Wada and Joe Shishido (see Figure 2), representing a new Japaneseness embodying disconcerting hybrids between Japanese and foreign heroes.

Figure 2.

Nikkatsu’s ‘Diamond Line’ poster. From left to right: Yūjirō Ishihara, Akira Kobayashi, Akagi Keiichirō and Koji Wada.

By the end of the 1950s, the so-called ‘Second Golden Age’ of Japanese cinema was coming to an end due to the competition of a new medium, the television. In 1958, the film industry reached a historical peak of production, with 547 annual releases, meaning that almost two new films were released every single day. However, by the turn of the decade, audiences had started to drop as viewers began to replace the cinema experience with watching films at home. One of the strategies developed by Big Studios was appealing young audiences with films featuring transcultural heroes and projecting exotic images of Japan that somewhat resembled Hollywood blockbusters. Nikkatsu marketed its youth icons under the label of Diamond Line that Nikkatsu used to renew the taiyōzoku with a new kind of film named Mukokuseki Action (‘action without nationality’). One of the most representative examples is the Wataridori series (1959–1962), starring Akira Kobayashi, who plays a cultural cross-breed role of ‘lone ranger’. These films develop an interesting adaptation of codes from Hollywood westerns, projecting a renewed fusion between the Occident and Japan. The film Plains Wanderer, also known as Rambler Rides Again (Daisogen no wataridori, 1960), directed by Takeichi Saitō, was shot in Hokkaido. Its landscapes imitate those of the Far West in the U.S. Kobayashi is featured with blatant cowboy elements, such as a fringe, a whip and even gestures borrowed from Alan Ladd and John Wayne, including the way of riding a horse. In fact, Kobayashi acknowledged that he had studied Alan Ladd’s way of drawing the pistol and John Wayne’s use of the rifle (Nishiwaki 2004, p. 152). The story revolves around a fight for the land rights of the Ainu people, whose iconography is a caricature echoing images of the Native American (Watanabe 1978; Centeno Martín 2016, p. 154). There were other examples that illustrate how this transcultural imaginary materialized in Japan in the postwar period. Keiichirō Akagi, nicknamed ‘Tony’ because of his resemblance to Tony Curtis, plays the role of a hitman wearing a leather jacket in the series Tales of a Gunman (Kenjū buraichō, 1959–1960), which is a reminder of James Dean and Marlon Brando (Nozawa 1997, p. 42). Joe Shishido played characters with a suspiciously foreign air inspired by actors of American B-movies such as those of Timothy Carey, Lee Marvin, and Henry Silva.

These heroes not only imported visual elements from Hollywood, they also embodied deeper moral, ethical, and narrative changes, such as the emphasis on individual liberty that had been legitimized after the Occupation period. Also, Yūjirō appeared on screen playing enka (Japanese ballade) with his ukulele and jazz and Japanese popular songs (kayokyoku) with the guitar, piano, and drums. Similarly, Kobayashi and Akagi were often featured playing a guitar in their films. Borders between American and Japanese popular culture were increasingly blurred by the second half of the fifties. These young stars became a kind of actor–singer, such as Elvis Presley, who began his cinema career with Love Me Tender (1956) and Gene Vincent, who debuted with The Girl Can’t Help It (1956). These films became a profitable business mainly due to the songs played on screen which became extraordinarily popular, being broadcast on the radio and edited in LPs.

Scholars have questioned the supposed airtightness of Japanese cinematic production in recent years. Authors such as Gregory Barret, Donald Kirihara, David Desser, Michael Raine, Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, and Aaron Gerow have evidenced that the cinematographic independence of this country is more complex than earlier expected. Its cultural production has unavoidably been traversed by streams coming from abroad. Contradictions in the notion of ‘national cinema’ can be found from the outset. Even before World War II, Marxists such as Eisenstein, one of the main defenders of Japanese specificity, and Akira Iwasaki (1931), stated that this industry was not alien to the capitalist circumstances found in Europe and the U.S. Also, Junichirō Tanizaki wrote in his In Praise of Shadows (Ineiraisan, Tanizaki 1933) that cinema had forced him to abandon the Japanese artistic and aesthetic tradition in favour of a Western conception of using light and shadow. It is well known that both Japanese filmmakers and filmgoers had been exposed to foreign films from the beginning of cinema—we mentioned above the influence of German directors on the Japanese early masters. However, it is important to note that the widely spread idea during the postwar period that Japanese film culture was isolated from the rest of the world was highly contradictory, given the unseen number of foreign films being distributed in Japan at the time, as we can see on the following graph (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Japanese and foreign films in Japan between 1952 and 1961. Grey: National productions. Black: foreign productions. Dotted: total. Vv. Aa. 1963. Eiganenkan. Tokyo: Jijitsūshinsha, p. 35.

6. Conclusions: Reframing Uniqueness through the Transnational

The examples provided above call into question approaches to Japanese cinema focusing on narrative and aesthetic patterns that are different from those developed in the West. That was the stream triggered by Burch’s text which finds a historical reason for this uniqueness: before the surrender in 1945, Japan had never been occupied by a foreign power (1979: 29). The country was free from a semi-colonial status such as that of China, or total dependence such as that of India, and as a consequence, its prolific film industry was able to consolidate completely original and autochthonous means of representation. Scott Nygren (2007) also supported this statement by claiming that Japanese originality was achievable thanks to the technical and economic autonomy of its film industry. Indeed, operators were trained and films started to be produced locally at a very early stage. In short, the self-sufficiency of its film studios would have allowed an interaction between cinema and its millenarian culture. In order words, Burch and Nygren claimed that the isolation of directors, screenwriters, and operators would have allowed them to make films free from Western influences and linked to their cultural tradition. However, this argument leaves two questions unresolved: First, is the functional autonomy of the Japanese film industry enough to create an essentially national cinema? Second, does this fact guarantee an absence of foreign influences?

This article does not attempt to deny the weight of the singularity of Japanese culture and the weight of its artistic tradition in cinema; but it seeks to highlight the fact that critics and scholars have often tended to neglect the sensitivity of Japanese filmmakers to foreign ideas and practices. The cases posed here show that Japan can and must be studied as an exceptional place for the international flow of images, without that entailing a loss of authenticity as authors in Japan and the West started to note from the 1980s. Yamamoto (1983) opened the discussion by interrogating seriously the impact of foreign influence on Japanese Cinema. This approach was followed by scholars such as Gerow (1993, pp. 23–36; 2010, pp. 1–14), who explains how cinema is a part of the cultural tradition of the 20th century, and full of multiple foreign influences. Similarly, David Desser (1988, p. 15) defines the Japanese New Wave as part of a movement expanding beyond its national borders. In addition, Gregory Barrett (1989) assesses archetypes in Japanese films that go back to folklore, mythology, and literature, while identifying others emerging from a conflict between tradition and modernity and from the interactions with the West.

These authors exemplify a sort of ‘post-national’ approach to cinema. In this sense, Donald Kirihara (1992) tackles the Japanese specificity warning about the contradictions related to essentialist Orientalism which some national cinema theorists have fallen into Kirihara (1996, pp. 501–19) demonstrates in his study of Mizoguchi that even classicism, which is often used as an example of the national character of the Japanese film, is a place of an extraordinary and rich internationalisation rather than a return to its traditions. As a consequence, we may ask what it is that makes Japanese films Japanese? As we have seen, to a great extent, it seems to be the Western gaze. In light of these contributions, it would be essential to reformulate the paradigm of Japanese national cinema within the global culture of images that flow incessantly. This does not have to undermine the role of Japanese tradition but, on the contrary, these approaches will be helpful to acknowledge and contextualise the Japanese film creation properly in the midst of an amalgam of practices, some from remote times and others from remote geographies.

Funding

This research was funded by The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation grant number [Ref. 197/13307].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1984. L’Émpire des signes. París: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Gregory. 1989. Archetypes in Japanese Film. The Sociopolitical and Religious Significance of the Principal Heroes and Heroines. London: Associated University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Audie. 1984. Japanese Film Directors. New York: Kodansha International. [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thomson. 1976. Space and Narrative in the Films of Ozu. Screen 17: 41–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell, David. 1988. Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell, David. 1994. Film history: an Introduction. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell, David, and Noël Carroll, eds. 1996. Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 29–74. [Google Scholar]

- Burch, Noël. 1979. To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno Martín, Marcos P. 2016. Transcultural Corporeity in Taiyōzoku Youth Cinema. Some Notes on the Contradictions of Japaneseness in the Economic Miracle. In Körperinszenierungenimjapanischen Film/Presentation of Bodies in Japanese Films. Edited by Andreas Becker and Kayo Adachi-Rabe. Frankfurt: Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Darmstadt: Büchner-Verlag, pp. 143–60. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno Martín, Marcos P. 2017. Failures of the Image: Backstage Look at the Early Film Portrayals of the Ainu People. Orientalia Parthenopea 17: 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno Martín, Marcos P. 2018. Contextualising N. G. Munro’s filming of the Ainu Bear Ceremony. Japan Society Proceedings. pp. 90–106. Available online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/25733 (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Crofts, Stephen. 1993. Reconceptualizing National Cinema/s. Quarterly Review of Film and Video 14: 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desser, David. 1988. Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to The Japanese New Wave Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Desser, David. 2006. A Filmmaker for all Seasons. In Asian Cinemas: a Reader and Guide. Edited by Dimitris Eleftheriotis and Gary Needham. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 157–65. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser, Thomas. 1989. New German Cinema: A History. Hampshire: British Film Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Endō, Shūsaku. 1955. Taiyo no kisetsuron. Ishihara Shintarō he no kugen. Bungakkai 11: 118. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, Stuart, and Paul Dundan, eds. 2009. La tribu du soleil et la nouvelle vague. InLe cinéma japonais. Hong Kong: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Gerow, Aaron. 1993. Celluloid Masks: The Cinematic image and the Image of Japan. Iris 16: 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gerow, Aaron. 2010. Introduction: The Theory Complex. Review of Japanese Culture and Society 22: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giuglaris, Shinobu, and Marcel Giuglaris. 1957. Le cinema Japonais. Paris: du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Harootunian, Harry D., and Masao Miyoshi. 2002. Learning Places: The Afterlives of Area Studies. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Higbee, Will, and Hwee Lim Song. 2010. Concepts of transnational cinema: towards a critical transnationalism in film studies. Transnational Cinemas 1: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higson, Andrew. 1989. The Concept of National Cinema. Screen 30: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Higson, Andrew. 2000. The Limiting Imagination of National Cinema. In Cinema and Nation. Edited by Mette Hjort and Scott MacKenzie. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, Akira. 1931. Eiga to shihonshugi [Cinema and Capitalism]. Tokyo: Ōraisha. [Google Scholar]

- Kirihara, Donald. 1992. Patterns of Time: Mizoguchi and the 1930s. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirihara, Donald. 1996. Reconstructing Japanese Film. In Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies. Edited by David Bordwelland Noël Carroll. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 501–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kracauer, Siegfried. 1947. From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film. 2985 edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mashita, Shinichi. 1956. Nihon no seishun. Seinentachi no kirokuyori [Japanese Youth. Fromthe Record of Youth]. FujinKōron 41: 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Toby. 2001. Global Hollywood. London: BFI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya, Ukichiro. 1956. Taiyōzoku no jidaisō [TaiyōzokuStages]. Bungakkai 9: 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Namba, Koji. 2004. Concerning Youth Subcultures in the Postwar Era Vol.1: From Taiyo-zoku to Miyuki-zoku. KwanseiGakuin Sociology Department Studies 3: 163–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki, Hideo. 2004. Kobayashi Akira densetsu. KinemaJunpō 14: 150–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, Kazuma. 1997. Akagi Keiichirō: ’hikari to kage’ nijūssai no fināre [Keiichiro Akagi: ‘Lights and Shadows’ of the Final at 20]. Tokyo: Seisei Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Nygren, Scott. 2007. Time Frames. Japanese Cinema and the Unfolding of History. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ōhashi, Ryōsuke. 1994. Kire. Das ‘Schöne’ in Japan [The Beauty in Japan]. Köln: DuMont. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, Stephen. 1991. Introduction. In Explorations in Film Theory: Selected Essays from Cine-Tracts. Edited by Ron Burnett. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. XV. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, Stephen. 1993. The Discourse of pictures: Iconicity and film studies. Film Quarterly 47: 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, Michael John. 2000. Ishihara Yūjirō: Youth, Celebrity, and the Male Body in late-1950s Japan. In World and Image in Japanese Cinema. Edited by Dennis Washburnand Carole Cavanaugh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–25. [Google Scholar]

- Richie, Donald. 1974. Ozu: His Life and Films. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Philip. 1984. History, Textuality, Nation: Kracauer, Burch and Some Problems in the Study of National Cinemas. Iris 2: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoul, Georges. 1966. Histoire du cinéma mondial. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, Mark. 2007. No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. Godalming: FAB. [Google Scholar]

- Standish, Isolde. 2012. The ephemeral as transcultural aesthetic: A contextualization of the early films of OzuYasujirō. Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema 4: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Yō. 2003. kyōijkushugi no botsuraku [The Wreck of Educationism]. Tokyo: Chūōshinsho. [Google Scholar]

- Tanizaki, Junichirō. 1933. Keizai ōrai. Tokyo: Nihon hyōronsha. [Google Scholar]

- Vv, Aa. 1963. Eiga nenkan. Tokyo: Jijitsūshinsha. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Takenobu. 1978. Fujimi no hīrō ni idomuKobayashiAkira no intabyū [Interview to AkiraKobayashi. ChallenginganImmortal Hero]. KinemaJunpō 15: 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Weinrichter, Antonio. 2002. Pantallaamarilla: el cine japonés. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Festival Internacional de Cine. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Kikuo. 1983. Nihon eiga ni okerugaikokueiga no eikyō [The Influence of Foreign Cinema on Japanese Cinema]. Tokyo: Waseda Daigaku Shuppanbu, p. 629. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Term coined by Noël Burch in his well-known Praxis du cinéma (1969) as the dominant mode of filmmaking developed by Hollywood studios and converted into the worldwide norm from the 1920s, whose aim is creating a totalizing illusionistic representation in which the audience is completely involved in the film through a spectatorial process of identification. Kenji Mizoguchi´s long takes, wide shots and off-centred compositions, as well as Yasujirō Ozu’s empty spaces and low camera, were seen as epitomes of national cinema. |

| 2 | Thus, Mizoguchi´s representation of self-sacrificing women have been assessed in relation to the Japanese concept of shibui (melancholy + serenity), his off-centred shots can be explained with the concept of kire-tsuzuki (‘cut’) theorised by Ryōsuke Ōhashi (1994) and Ozu´s depiction of the cycles of life, silence, and emptiness are analysed using elements from Zen Buddhism and Japanese cultural and literary tradition such as the mujō (‘awareness of impermanence’), mono no aware (‘pathos of things’) or mu (‘emptiness’) (see Bordwell 1988; Desser 2006). |

| 3 | Also in Bordwell, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. 1988. |

| 4 | Cfr. Variety’s Film Review, R. Bowkers, New York, 22-10-1952. |

| 5 | Also in Bordwell, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. 1988. |

| 6 | To know more about this linguistic model applied to images, see (Prince 1993). |

| 7 | Stars like Hiroshi Kawaguchi, the protagonist of Punishment Room, constantly asked the hairdresser for a ‘James Dean style’, Shūkan Yomiuri, 27 May 1957. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).