Abstract

The small business sector is regarded as a catalyst of employment for the largest number of people around the world. To reduce massive unemployment and inequality in the country, the Government of South Africa introduced various initiatives to stimulate and support small businesses, and the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) is one such initiative. The enterprise development approach, which seeks to transfer income to poor households in the short to medium term, is one of the delivery mechanisms of the EPWP. This study critically assesses the impact and effectiveness of the training and support interventions provided to small businesses through the EPWP. The study employs a quantitative research method due to the size, availability, and ease of access of the participants, and the entire population of 20 small businesses, supported by the EPWP in the Pretoria region, was sampled. A questionnaire-based survey was conducted. The study demonstrates that the training intervention provided by the EPWP has a positive impact and achieves its intended goal of enhancing the business management skills of participants. It also reveals an interesting outcome, i.e., that the majority of the participants are women. The study also identified some weaknesses in the programme, which led to the recommendation that long-term support mechanisms are essential for ensuring the sustainability of emerging enterprises.

1. Introduction

Globally, post industrialisation has seen an increase in the role of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are becoming the lifeblood of economies and the best hope for employment generation for the labour surplus (Sippitt 2014). Similarly, South Africa relies on SMEs to generate sufficient employment to absorb the excess unemployed masses. As such, the Government of South Africa (GSA), recognising a decline in the traditional labour-absorbing sectors such as mining, agriculture, and manufacturing, introduced a melange of programmes and initiatives intended to develop and support emerging small businesses Czemiel-Grzybowska (2013). It is therefore important to assess and evaluate some of these interventions to determine their effectiveness in addressing their intended goals. The purpose of this article is to critically assess and evaluate the impact as well as the effectiveness of training and support interventions provided to small businesses in one of the GSA initiatives, the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP).

2. Background

Small businesses are considered by governments worldwide to contribute to economic stability and growth as well as new job creation, social cohesion, and development (Hyder and Lussier 2016). During challenging economic times, small businesses act as the “economic shock-absorbers” to cushion economies from total collapse. They enable the wheels of economies to keep turning during difficult times. Thus, nurturing and developing small business is a priority for many countries, both developed and developing ones. According to Hande (2016) small- and medium-sized enterprises are the drivers of socio-economic development due to the positive role they play in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth.

For this reason, in South Africa, various programmes and initiatives have been put in place by the Government to develop and support small businesses, particularly those that are owned by previously disadvantaged individuals (PDIs) and designated groups, such as the youth, women, and persons with disabilities. These programs are implemented by all spheres of government (national, provincial, and local government). Among this array of initiatives is the EPWP, which started in 2004 as a result of the 2003 Growth and Development Summit (GDS) that adopted the theme that gave birth to the EPWP. The objective of the Programme is to provide an avenue “for labour absorption and income transfers to poor households in the short- to medium-term” Expanded Public Works Programme Performance Report (2017). One of the delivery strategies of the EPWP is the enterprise development approach, which focuses on supporting and developing emerging enterprises including co-operatives to leverage additional work opportunities. The small business support model for the EPWP Enterprise Development Programme (EPWP-EDP) comprises interventions that facilitate access to markets, access to development finance, linkages to business development support services, and access to training/skills development related to business management. These are all in-house services provided through the EPWP-EDP.

3. Problem Statement

The government has initiated various SME development support interventions (including training and financial/non-financial support) in order to contribute to job creation and economic growth. The enterprise development intervention is one of the delivery mechanisms of the EPWP, which is aimed at developing and supporting small businesses within the Programme.

The SME development and support intervention is provided for a particular fixed period, and a phased-out approach (i.e., steady withdrawal towards the end of the period) is used. This is to allow small businesses to operate on their own. However, small businesses continue to struggle, with very few enterprises continuing to thrive after the support has been phased-out. Hence, the effectiveness of the support provided to small businesses by the EPWP and its impact are investigated in this article.

4. Article Objectives

The purpose of this article is to critically assess the impact and effectiveness of training and support interventions provided by the EPWP to small businesses within the programme.

5. Literature Review

5.1. Introduction

The literature review forms a foundation for the study, as it provides a critical and historic background and the theory on the subject under review, from both international and local perspectives. In this case, the focus is on the role of training and support in developing small businesses. Webster and Watson (2002) noted that a review of prior, relevant literature is an essential feature of any academic project.

5.2. EPWP Background and Origins

According to the (EPWP 2017), the programme is defined as the nationwide government-led initiative, with the objective of providing work opportunities and income support to poor and unemployed people in the short to medium term. It was introduced as a result of the Growth and Development Summit (Nedlac 2003), a national conference attended by representatives of labour organisations, civil society organisations, business and government, led by the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC). During the summit, a number of resolutions and agreements were reached, including the implementation of the EPWP as a poverty alleviation and income relief program that provides temporary work to the unemployed and ensures that they participate in socially useful activities (Nedlac 2003).

The EPWP comprises of four sectors EPWP (2013): (1) The infrastructure sector, led by the Department of Public Works (DPW), which advocates the use of labour-intensive methods in delivering construction and maintenance services to public sector funded infrastructure projects; (2) the social sector, led by the Department of Social Development (DSD), which provides work opportunities to unemployed and unskilled people through the delivery of social development and community protection services such as early childhood development (ECD), home community-based care (HCBC), and school nutrition programmes; (3) the environment and culture sector, led by the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), which involves employing people to work on projects that improve their local environment, spearheaded by various departments, such as sustainable land-based livelihoods, waste management, etc.; and (4) the non-state sector (NSS), led by both the DPW and Department of Cooperative Governance (DCoG), which uses wage subsidies to support non-profit organisations (NPOs) on their community development initiatives. The NSS comprises two aspects, namely the Community Work Programme (CWP) and NPOs programme. The CWP is area-based and is managed by the DCoG.

5.3. The EPWP Enterprise Development

According to the EPWP (2017), enterprise development (ED) is a delivery strategy of the EPWP, and targets the development of emerging enterprises, including co-operatives, to leverage additional work opportunities. The EPWP ED support services model for the sectors includes:

- (1)

- Facilitating access to training/skills development related to business management;

- (2)

- Facilitating linkages to business development support services;

- (3)

- Capacitating SMEs to comply with legislative requirements;

- (4)

- Facilitating access to markets;

- (5)

- Facilitating access to development finance;

- (6)

- Facilitating exit opportunities for the National Youth Service (NYS) and Vuk’uphile Programmes led by the DPW; and

- (7)

- Providing guidance to EPWP sectors and public bodies on exit opportunities.

Through this support, the EDU aims to sustain the growth and development of SMEs by identifying opportunities where individual businesses and co-operatives can be developed, thereby maximising the creation of work opportunities, which is in line with EPWP objectives.

5.4. The Model of EPWP Enterprise Development Support

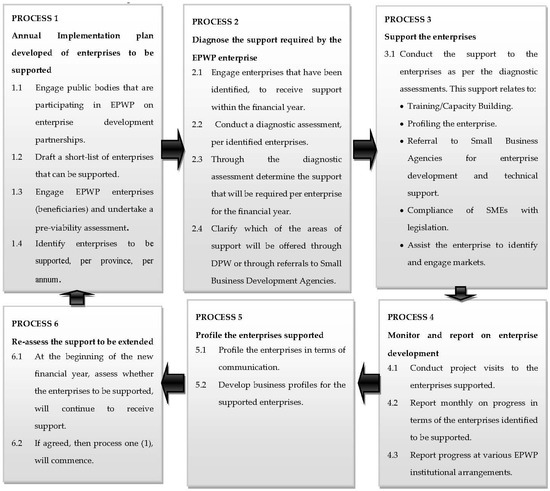

The EPWP enterprise development support includes, among other things, facilitating access to training/skills development related to business management EPWP (2017). This is a form of in-house training provided by the officials within the EPWP EDU. To carry out this function, they use the process flow model as outlined in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The EPWP Enterprise Development Support Model. Source: EPWP policy on small, medium, and micro enterprises, (EPWP 2013).

5.5. Theoretical Framework

Evaluating the impact of the training and support intervention on small businesses in the EPWP is carried out using the “Theory of Change” framework. This theory is considered to be relevant, because it is focused not just on generating knowledge about whether a programme is effective, but also on explaining whether the methods used are effective (Allen et al. 2017 and Breuer et al. 2016).

The theory of change is the new way of analysing the phenomena motivating programmes and initiatives that bring about social and political change. Using the theory of change approach, Robinson et al. (2004) argued that the guiding principle behind a successful entrepreneurship development programme is the notion that initiatives should be aimed at strengthening the performance of small-to medium-sized rural enterprises, and this will ultimately change the way small businesses in rural areas perform, thereby improving the socio-economic conditions of the rural people that they serve. This is exactly the case under investigation in this article, i.e., whether the EPWP small business support for initiatives improves the skills of entrepreneurs and changes the way they run their businesses.

5.6. Small, Medium, and Micro Enterprise Description

According to Katua (2014), the small, medium, and micro enterprise (SMME) sector has widely been accepted as the engine of economic growth and poverty eradication around the world. The role of SMEs in economic development and employment creation has occupied most of the discussions among governments, policy makers, academicians, researchers and scholars. However, the meaning of an SME has remained different across countries and different sectors in the same country.

In South Africa, the National Small Business Amendment Act (2003) defines a small business as “[...] a separate and distinct business entity, including co-operative enterprises and nongovernmental organisations, managed by one owner or more, which, including its branches or subsidiaries, if any, is predominantly carried out in any sector or sub-sector of the economy mentioned in Column I of Schedule 14 [...]”. The Act classifies the SMMEs in terms of the total full time equivalent of paid employees, the total turnover and gross asset value, excluding fixed property, depending on the different industries/sectors, such as mining, transport, finance, trade etc. It further categorizes small businesses in South Africa into distinct groups, namely, survivalist, micro, very small, small, and medium, hence the use of the term, “SMME”, for small, medium and micro-enterprises. However, the terms, “SMME” and “SME”, are used interchangeably in South Africa. (BASA 2017).

5.7. Training of Small Businesses: Global and South African Perspectives

Mungai (2012) states that the success of entrepreneurs’ development and management in any enterprise depends on their capacity to develop human resources through training and their ability to start a business, as well as create jobs, products and services that can compete in the global market. This view is further echoed by Manimala and Kumar (2012), who indicate that strengthening the internal capabilities of SMEs has become a top priority nowadays and is positioned as an alternative or supplementary strategy for SMME development. Training is recognized as an important tool for developing the internal capabilities of SMEs. The study by Afolabi and Macheke (2012) found a very strong relationship between training in business and entrepreneurial skills and their contribution to the success of SMEs.

However, contrary to general beliefs, some researchers have revealed that SMEs themselves do not see the importance of training nor do they put emphasis on training. Thus, they tend not to acknowledge training as something that adds value to them and their businesses, according to Yahya et al. (2012). This view is also shared by Karmel and Cully (2009) who found that low-level SMEs, referred to by Sewgambar (2015) as survivalist enterprises (micro-enterprises that depend solely on their daily income, without external support), regard training as a waste of time in terms of their immediate needs.

Nonetheless, Ranyane (2014), in a study of the relationship between business performance and the level of training in 70 micro-enterprises in Nigeria, revealed that 49% of the 51% of participants who had received training in their areas of business were doing well in business, while 60% of the participants who were not trained reported that their businesses were poorly performing. This study therefore highlighted the importance of the role played by training in business performance.

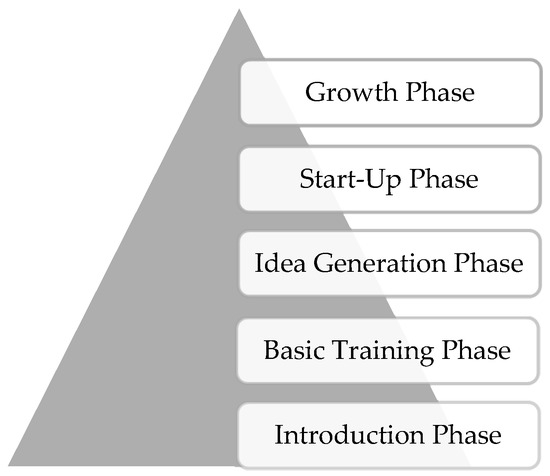

To develop and support small businesses, Ranyane (2014) developed a five-phase training model as shown in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2.

Phase training strategies model. Source: Adapted from Ranyane (2014); training phases for the survivalist entrepreneurs to become viable in business activities.

This model emphasizes the approach or intervention based on the phase/stage of the entrepreneur in the business. Studies reveal that supporting small businesses requires a holistic approach, as there is no “one-size fits all” in small business development (Munyanyiwa et al. 2016). Each phase has a specific objective for the entrepreneur:

- (1)

- Introduction Phase: This phase assists entrepreneurs in gaining a broader understanding of a business and the motive for starting a business. It further emphasizes how businesses can become a form of employment. Finally, it highlights the issues surrounding being an entrepreneur. This phase is regarded as an “introspection phase”, as the entrepreneur is discovering himself/herself and checking whether this is a route to take.

- (2)

- Basic Training Phase: Once the entrepreneurial abilities and attributes have been identified, the entrepreneur is provided with the requisite skills and further capacitated for identifying opportunities. It is in this phase that the decision on the type of trade to be chosen as well as financial assistance with the registration of the business are undertaken.

- (3)

- Idea Generation Phase: During this phase, the entrepreneur is assisted with writing a business plan and growth plan. The entrepreneur is further assisted with setting up a business and mobilizing financial support.

- (4)

- Start-up Phase: This refers to the running of a business as per the business plan, i.e., putting the first three phases into practice and mentoring and guiding the commencement of the programme.

- (5)

- Growth Phase: This phase is focused on expanding the business as per the growth plan and continuing the mentoring and guiding of the entrepreneurs.

5.8. Effective Support to Small Businesses and Best Practices

Supporting small businesses has been identified by government, both in developing and developed countries, as an important intervention due to their contribution to the economy. Bouri et al. (2011) regard the small businesses sector as the backbone of the economy in high-income and low-income countries. In order to improve support provided to small businesses, structured interventions are important. For example, Afolabi and Macheke (2012) recommend that structured training intervention is very important and should be developed in relation to all identified skill sets, and that a training plan for emerging entrepreneurs should focus largely on the soft skills, management skills and the technical skills of the proposed venture. Furthermore, Ntlamelle (2015) outlines three critical small business support models that can assist entrepreneurs in defying market failures that threaten many in South Africa, viz., mentorship, incubation, and informal/unstructured support models. These models play a key role in moulding small businesses.

6. Methodology

The aim of this article is to evaluate the impact of training and support interventions of EPWP to SMEs. To achieve this objective, a diagnostic research design, as defined by Kothari (2004) to measure the frequency with which something occurs or whether certain variables are associated, is most appropriate. Here, the researcher wants to know about the root cause of the problem. According to van Wyk (2014), this describes the factors responsible for the problem or impact of the situation.

A quantitative method is utilized in this article. Eriksson and Kovalainen (2015) defines this as a research strategy that emphasises quantification in the collection and analysis of data, while Muijs (2012) defines it as the method that explains phenomena by collecting numerical data and analysing them using mathematics-based methods (in particular, statistics). The positivism (positivist) paradigm is also adopted, because according to Heuschele (2014), it assumes that reality is objectively given and that it can be reflected and systematized by empirical methods, which is in line with the objectives of the study. In this article, a questionnaire is used as an instrument to collect data.

The entire population was sampled due to its small size, i.e., 20 small businesses in the Pretoria Region as well as, due to ease of access, the entire population. A questionnaire was used as an instrument to collect data. Its design was based on the three broad/main research questions and uses the information that was gathered in the literature review section of this study. The design of the questionnaire was such that it enabled the researcher to collect quantitative data in order to fully explore the subject being investigated. It contained a total of 32 questions that were divided into two main sections.

Section A: Covers the demographic information of a participant, including the number of years they have been in business, the form of business they are involved in (sole trader, partnership, cooperative, private company and public company), and lastly, the role of a participant in business with regard to whether she/he is a single owner/director, co-owner/co-director, supervisor, or a general worker. This section has a total of five questions.

Section B: This section is considered to be the core of the study/questionnaire. It covers the main objectives of the research and is divided into three sub-themes.

Due to the ease of access and availability of the research participants, the questionnaires were then distributed to the entire population, and a 100% response rate was achieved. The primary quantitative datum is first captured using the Microsoft Excel spread sheet for coding purposes. (Hussain et al. 2013) state that the data obtained from the questionnaire need to be statistically coded in order to determine variation, and this process involves assigning numbers to responses, so that the data can be grouped into categories. The data is then transferred to the SPSS for Windows (software) to be analysed. SPSS is the most widely used computer software for the analysis of quantitative data, according to Bryman (2008). The study uses descriptive or inferential statistics to conduct the analysis of data. Dieronitou (2014) defines descriptive statistics as a method of organising, summarizing, and presenting data in a convenient and informative way, using graphical and numerical techniques. Inferential statistics is defined as a method used to draw conclusions or inferences about the characteristics of a population, based on sample data (Muijs 2012).

7. Data Presentation, Analysis, and Interpretation

The literature review above noted that the small, medium, and micro enterprise sector has widely been accepted as the engine of economic growth and poverty eradication around the world (Katua 2014). Supporting small businesses has been identified by government both in developing and developed countries as an important intervention due to their contribution to the economy (Bouri et al. 2011). This section presents, analyses and discusses research findings on the impact of training and support interventions on small businesses in the EPWP, as part of the Government initiative to develop and support small businesses in order to contribute to job creation and economic growth. The following are the highlights of the research findings:

Socio-Demographic Variables

- The results regarding participants’ socio-demographic variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic variables.

Table 1. Socio-demographic variables. - The study revealed that most of the participants were female (80%). These are positive results, as they reflect that the programme surpassed the EPWP target of 55% women in all its initiatives.

- It further found that more than half (55%) of the participants mentioned that they had been in business for a period of between two and three years, which means that the support intervention targeted the right people for addressing phenomena of small businesses failing within their first few years of existence, as less than half of newly established businesses survive beyond five years according to Brink et al. (2013).

- The study results indicate the positive impact and high level of effectiveness of the EPWP, as a government training support intervention for assisting and developing small businesses to strive in future. Nodada (2011) found that among the reasons for the failure of small businesses is lack of funding and capital, insufficient support from the government and a lack of business and financial management skills. This view is further supported by Smith and Sandra (2006) and cited by Afolabi and Macheke (2012), who state that business skills are very important for keeping the business afloat. In addition, the study by Afolabi and Macheke (2012) further found a very strong relationship between training in business and entrepreneurial skills and the benefit it could have in relation to the success of SMEs.

- When asked about their business management skills, before they participated in this programme, the majority (80%) of the participants considered their business management skills to be low before they participated in the EPWP Support Programme. However, when asked about their skills levels after taking part in the programme the majority of the participants (85%) indicated that their business management skills were high (improved) after the EPWP training support programme.

- When asked about whether they apply the skills and knowledge gained from the EPWP Training Programme, the majority of the participants (95%) responded positively to the question. This indicates that the training provided by the EPWP to small businesses is appropriate and relevant to their day-to-day operations, as they are able to use the acquired skills and knowledge. Niazi (2011) points out that training plays a crucial role in the growth and success of a business.

- With regard to whether the EPWP Training Programme assisted in addressing the financial management and record management skills gaps, 85% and 65% of participants, respectively, strongly agreed with this statement. This intervention has instilled a permanent change in the participants’ skills and knowledge, which, according to Smith and Sandra (2006), is the core of training and experiential learning.

- The study further revealed that 100% of the participants are fully compliant with the South African Revenue Services (SARS) and Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) requirements. This is very important, as Somers et al. (2014) argued, because SME owners need to make sure that they abide by the regulations and laws of the country in which they operate.

- However, the same cannot be said when it comes to the legislation relating to the Department of Labour (DoL), such as Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (COIDA) and Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHS), where the level of compliance was registered at only 40% and 0% of participants, respectively. Scott (2015) cautions that, when a business fails to meet the government guidelines and policies, this may result in consequences, such as lawsuits with the government itself or with the affected stakeholders (other businesses or consumers/clients and workers), immense fines, or, in the worst case scenario, the dissolution of the entire business.

- To evaluate the user-friendliness of the training material and to determine whether the support provided by EPWP Small Business Development Programme was in in line with the needs of entrepreneurs, training should be specifically packaged and designed to address the specific needs of trainees, the training material must be in a language that is easy and well understood by the entrepreneurs, including the use of relevant and practical examples by trainers, as indicated in Egelser and Rena (2013). Of the participants, 100% felt that the training material was user-friendly and that the training program addressed their needs.

- As with any intervention, according to Maluleke (2013), most of the government SMME training and intervention initiatives are not designed and packaged for any target groups or sectors, and trainers fail to take into consideration the diverse needs and education levels of SMEs. The participants were asked whether assessments were conducted prior to training in order to identify skill gaps and package the intervention to address the specific needs rather than general needs. Of the participants, 100% agreed that indeed assessments were conducted prior to the training intervention, which means that the training was customized to address the specific identified gaps.

- When asked whether the time dedicated by EPWP officials to supporting small businesses was sufficient, there was a mixed bag of responses, where 15% strongly agreed with the statement, 45% agreed, 15% disagreed, 20% strongly disagreed, and only 5% were neutral. These results are inconsistent with the founding principles of the EPWP in terms of the EPWP Policy on Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (EPWP 2013), where the policy emphasizes coaching and dedicated support provided to small businesses and the monitoring of their growth. Despite the fact that the majority (60%) of participants generally agreed with the statement, more attention should be paid to the remaining 40% who did not agree with the statement, to ensure that this intervention programme achieves its objectives.

- In the same breath, 60% of participants indicated that aftercare support was not provided. This is not aligned with small business development principles. When the government invests in small business support programmes, dedicated after-care support and monitoring mechanisms must be in put in place to sustain the initial achievements. Czemiel-Grzybowska (2013) argues that dedicated and structured support systems, policies and programmes must be in place before any intervention can be carried out, allowing small businesses to develop, be nurtured, and grow.

- When asked whether the EPWP support has assisted the participant to tender and market his/her business independently, 90% agreed with the statement, while 95% of participants believed that this intervention improved their understanding of running and managing their business. As argued by McKenzie and Woodruff (2016), training and support interventions are one of the most common forms of active support provided to SMES around the world. These results suggest that the Expanded Public Works Programme for small businesses has a positive role and contribution.

These findings indicate and highlight the important role played by the EPWP small business support intervention in improving the skills of entrepreneurs and the development of the SMEs in general. Afolabi and Macheke (2012) argued that business management skills are very important in keeping the business afloat. This view is further supported by Cassim et al. (2014), who found that education and training are some of the most important factors hampering entrepreneurial activity in South Africa. Therefore, in order to develop and support small, medium, and micro enterprise sectors, a concerted effort by government must be put in place. This is evident from the South African Government’s Integrated Strategy on the Promotion of Entrepreneurship and Small Business (2005), which emphasized the government’s commitment to supporting SMEs for their role in the contribution to the growth and performance of the economy.

The findings further revealed that this intervention directly benefited one of the key demographic groups in the EPWP, which is that of women, whereby the programme surpassed the EPWP targets of 55% women in all its initiatives. (EPWP 2013).

Despite the numerous positive achievements of the programme, the study also revealed areas of weakness, requiring improvement, such as compliance to labour legislations, where the study revealed that only 40% and 0% of participants recorded compliance with COIDA and OHS, respectively. Furthermore, the study revealed a lack in after-service support by EPWP officials, which means that post training support is not provided to the SMEs. This is inconsistent with the argument of Maluleke (2013) that post-training support programmes and after-care programmes are important for developing and sustaining SMEs.

According to Das and Imon (2016), before one conducts any formal statistical analysis, it is essential to assess the normality of the data in order to ensure that the findings are not skewed to one area. The most commonly used methods are correlation, regression and experimental design. These methods are used to see if the observations follow a normal distribution. As a result, it is assumed that the population from which the sample is extracted is normally distributed. However, as indicated earlier in this study, due to the great availability of the research participants, the population size and the sample size are the same. The normality test in Table 2 shows that the overall scores were normally distributed. Further analyses were conducted using a parametric test, such as a t-test, ANOVA test, and Pearson’s correlation test, as shown in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, below.

Table 2.

Tests of normality.

Table 3.

t-tests.

Table 4.

Independent samples test.

Table 5.

ANOVA test.

Table 6.

Number of years in business.

Table 7.

Type/form of business.

Table 8.

Group Statistics.

Table 9.

The Pearson’s correlation test output.

Comparing the mean score for construct 1 and construct 2, the descriptive analysis shows that male participants had a higher mean value for both the constructs, as shown in Table 3. However, the t-test results indicated that the mean values were similar between males and females, for both of the constructs (p > 0.05).

An ANOVA test was conducted to compare the mean values for more than two groups, for both of the constructs, as shown in Table 4 and Table 5. It was found that participants who were 41–50 years old had the highest mean score for construct 1 and for construct 2. However, the ANOVA test did not find any significant mean differences among the different age groups with regard to construct 1 and construct 2 (p > 0.05).

Comparing the mean score for construct 1 and construct 2, descriptive analysis showed that participants who had been in business for 4–5 years had a higher mean value for both of the constructs, as shown in Table 6. However, the t-test results indicated that the mean values were similar between those who had been in business for 2–3 years and those who had been in business for 4–5 years for both of the constructs (p > 0.05).

Comparing the mean score for construct 1 and construct 2, descriptive analysis showed that the proprietary limited form of business had a higher mean value for construct 1 and a lower mean value for construct 2, while the cooperative form of business had a higher mean value, as shown in Table 7. However, the t-test results indicated that the mean values were similar between proprietary limited and cooperative forms of business for both of the constructs (p >0.05). This is in line with the EPWP policy (2013) of supporting cooperatives due to the number of people who benefit from a cooperative, as compared to a proprietary limited, form of business.

Comparing the mean score for construct 1 and construct 2, descriptive analysis showed that the owner/director of the business had a higher mean value for construct 1 and a lower mean value for construct 2, while the co-owner/co-director had a higher mean value for construct 2, as shown in Table 8. However, the t-test results indicated that the mean values were similar between the owner/director and co-owner/co-director of the business for both of the constructs (p >0.05).

The Pearson’s correlation test in Table 9 did not find any significant relationship between the two constructs (r = 0.184, p = 0.437). Therefore, we cannot determine any the relationship between these two constructs, which is similar to the finding of Das and Imon (2016).

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

8.1. Conclusion

The overall purpose of the article was to critically assess and evaluate the impact and effectiveness of training and support interventions provided by EPWP to small businesses within the programme. The article looked at both global and South African perspectives on small business support, starting with how small business are defined in South Africa and other countries.

The article revealed that:

- The programme benefited the intended recipients, who are mostly women, in terms of the EPWP demographic targets.

- Cooperatives also constitute the segment of the SME that directly benefited from this programme as the majority of the participants were members of cooperatives. Again, this is consistent with the objectives of EPWP and the government in general in relation to supporting cooperatives that are predominantly owned by women.

- When it comes to the effectiveness and impact of the programme, the overwhelming majority of participants (95%) responded that the training provided by the EPWP assisted their businesses.

- Moreover, in terms of managerial skills, most of the participants joined the programme with very low managerial skills, but when they left the programme their managerial skills were improved, and the majority of them are applying the skills that they acquired from the training programme.

- Compliance with legislative requirements is a critical area that was assessed by this article. There were high compliance levels when it comes to CIPC and SARS legislations, but not in the case of DoL legislation, particularly OHS and COIDA.

- The design of the training material and training approach (its flexibility) was found to be user-friendly and to accommodate the needs of participants.

- One hundred percent (100%) of the participants responded positively to the design of the training material, and it was found to be user-friendly and to respond to the needs of entrepreneurs/business owners.

8.2. Recommendation

The findings of the article revealed that the training and support interventions provided by the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) to small businesses within the programme has a positive impact and is effective. The study further revealed certain areas that need attention, such as “after-service” support, i.e., follow-ups on the supported small businesses, in order to improve the programme. Based on the study findings, it is recommended that an all-inclusive small business support be implemented. The EPWP small business support programme suffers from what I refer to as a “piecemeal and referral syndrome”. The Programme does not implement support initiatives from start to finish due to the challenge of always receiving small businesses recruited externally by other sub-programmes, without vigorous testing of the entrepreneurial ability or potential of an individual. It seems as if the tough economic conditions have become a motivation for unemployed persons to consider opening a small business, without the right appetite or attitude for it. This creates a difficulty in moulding them, since they are in the programme with the wrong motives.

Another challenge is that the small business support model does not have dedicated funding and therefore cannot provide what I refer to as an “end-to-end small business support solution”. It is against this backdrop that a holistic and all-inclusive small business support programme is proposed, to be implemented by EPWP, coupled with the provision of funding, access to the market in the form of projects or contracts, and dedicated support to ensure a healthy and comprehensive enterprise development programme. The focus must never be on increasing the number of supported SMEs, as it is in many other programmes, but rather the quality of the support and the outcomes of the support, which should be the cornerstone of the intervention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.; Data Capturing, L.D; Formal analysis, L.D.; Writing—original draft, L.D.; and Writing—review and editing, L.D. Review and supervision E.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on Lungisani Dladla’s Masters of Commerce in Leadership Dissertation completed at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Graduate School of Business and Leadership.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Afolabi, Bola, and Richard Macheke. 2012. An Analysis of Entrepreneurial and Business Skills and Training Needs in SMEs in the Plastic Manufacturing Industry in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. International Review of Social Sciences and Humanities 3: 236–47. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Will, Jennyffer Cruz, and Bruce Warburton. 2017. How Decision Support Systems can benefit from a Theory of Change approach. Environmental Management 59: 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banking Association of South Africa (BASA). 2017. Available online: http://www.banking.org.za/what-we-do/sme/sme-definition (accessed on 18 June 2017).

- Bouri, Amit, Breij Mark, Diop Magatte, Kempner Randall, Klinger Keely, and Bailey Stevenson. 2011. Report on Support to SMEs in Developing Countries through Financial Intermediaries. New York: Dalberg, November. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, Erica, Lucy Lee, Mary De Silva, and Crick Lund. 2016. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implementation Science 11: 63. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, Annekie, Michael Cant, and Andre Ligthelm. 2013. Problems experienced by small businesses in South Africa. Paper presented at 16th Annual Conference of Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand, Ballarat, September 28–October 1; vol. 28, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, Alan. 2008. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassim, Shahida, Soni Paresh, and Anis M. Karodia. 2014. Entrepreneurship Policy in South Africa. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review 3: 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Czemiel-Grzybowska, Wioletta. 2013. Barriers to financing small and medium business enterprises in Poland. BEH Business and Economic Horizons 9: 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieronitou, Irene. 2014. The ontological and epistemological foundations of qualitative and quantitative approaches to research. International Journal of Economics 2: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Egelser, Sophia, and Ravinder Rena. 2013. An evaluation of the effectiveness of training on entrepreneurship development in Windhoek. Available online: www.essa2013.org.za/fullpaper/essa2013_2773 (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- Expanded Public Works Programme Performance Report (EPWP). 2017. For the Period April 2016 to March 2017 (YEAR 3 of Phase 3). Available online: www.epwp.gov.za (accessed on 18 June 2017).

- EPWP. 2013. Policy on Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise. Available online: www.epwp.gov.za/index.html (accessed on 18 June 2017).

- Eriksson, Päivi, and Anne Kovalainen. 2015. Qualitative Methods in Business Research: A Practical Guide to Social Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hande, Karadag. 2016. The Role of SMEs and Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth in Emerging Economies within the Post-Crisis Era: An Analysis from Turkey. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Development 4: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Heuschele, Fabian. 2014. Eliminating Distance between CEOs and Employees: An Explorative Study of Electronic Leadership Enabled by Many-to-One Communication Tools. Ph.D. thesis, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. Athar, Tariq Elyas, and Omar A. Nasseef. 2013. Research paradigms: A slippery slope for fresh researchers. Life Science Journal 10: 2374–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, Shabir, and Robert N. Lussier. 2016. Why businesses succeed or fail: a study on small businesses in Pakistan. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 8: 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katua, Ngui Thomas. 2014. The role of SMEs in employment creation and economic growth in selected countries. International Journal of Education and Research 2: 461–472. [Google Scholar]

- Karmel, Tom, and Mark Cully. 2009. The Demand for Training. Conference Paper. National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Australia, Academy of Social Sciences seminar. Sydney in September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Keya Rani, and Rahmatullah A. H. M. Imon. 2016. A Brief Review of Tests for Normality. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, Chakravanti Rajagopalachari. 2004. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Maluleke, Amukelani. 2013. Challenges faced by Seda in Providing Training and Mentorship Support to SMEs. Master’s dissertation, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Manimala, Mathew J., and Sudhir Kumar. 2012. Training Needs of Small and Medium Enterprises: Findings from an Empirical Investigation. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review 1: 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, David, and Christopher Woodruff. 2016. Business practices in small firms in developing countries. Management Science 63: 2967–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungai, Bernadette. 2012. The Relationship between Business Management Training and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises’ Growth in Kenya. Ph.D. thesis, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Muijs, Daniel. 2012. Doing Quantitative Research in Education. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Munyanyiwa, Takaruza, Mutsau Morgen, Rudhumbu Normam, and Svotwa Douglas. 2016. An Investigative Study into Perspectives and Experiences of Incubates at the Chandaria Business Innovation and Incubation Centre at the Kenyatta University. Journal of Education and Practice 7: 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Niazi, Bras. 2011. Training and development strategy and its role in organizational performance. Journal of Public Administration and Governance 1: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedlac. 2003. Growth and Development Summit Agreement: 7 June 2003. Available online: https://sarpn.org/documents/d0000370/P355_Nedlac_Agreement.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- Nodada, Xoliswa. 2011. An Analysis of the Factors that Lead to SMME Failure. Master’s dissertation, University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Ntlamelle, Tshepo. 2015. The Efficacy of SMME Incubation as a Strategy for Enterprise Development in South Africa. Master’s dissertation, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Monroe. 2015. What Makes a Small Business Succeed or Fail. Professional Manager. Available online: www.managers.org.uk/insights/.../2015/.../what-makes-a-small-business-succeed-or-fa (accessed on 11 July 2017).

- Somers, Gillian, Cain Julie, and Jeffery Megan. 2014. Essential VCE Business Management, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ranyane, Kgantsho A. 2014. A Support Framework for the Survivalist Entrepreneurs in the Free State Province, South Africa. Ph.D. thesis, University of Free State Business School Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, Bloemfontein, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Kenneth L., Dassie Wylin, and Ralph D. Christy. 2004. Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development as a Rural Development Strategy. Southern Rural Sociology 20: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sewgambar, Ranjan. 2015. The Development of Business Management Skills through a Youth Enterprise Development Entrepreneurship Programme (SAB KickStart). Master’s dissertation, University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Sippitt, Michael. 2014. Cluster, Technology & Innovation: Global Perspective and relevance of Bangladesh. Paper presented at Sustainable SME Development in Bangladesh Conference, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 7 May. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Elroy E., and Perks Sandra. 2006. Training Interventions Needed For Developing Black Micro-Entrepreneurial Skills in the Informal Sector: A Qualitative Perspective. SA Journal of Human Resource Management 4: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, Brian. 2014. Research Design and Methods Part I. University of Western Cape. Available online: https://www.uwc.ac.za/Students/Postgraduate/Documents/Research_and_Design_I.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- Webster, Jane, and Richard T. Watson. 2002. Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. MIS Quarterly 26: xiii–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Yahya, Ahmad Zahiruddin, Md Said Othman, and Abd Latiff Sukri Shamsuri. 2012. The Impact of Training on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Performance. Journal of Professional Management 2: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).