Genome-Wide Analyses Revealed Remarkable Heterogeneity in Pathogenicity Determinants, Antimicrobial Compounds, and CRISPR-Cas Systems of Complex Phytopathogenic Genus Pectobacterium

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains Information, Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

2.2. Phylogenomic Analyses

2.3. Basic Statistics and Genomic Profile Features

2.4. General Genomic and Proteome Analyses

2.5. Codon and Amino Acid Usage and Pan-Core Genome Analyses

2.6. Genomic Islands (GI) Prediction

2.7. Analyses of Pathogenicity, Virulence, Antimicrobial Gene Clusters and CRISPR-Cas

3. Results

3.1. General Genomic Features and DNA Structure Properties

3.2. Phylogenetic Relationships within Pectobacterium Genus

3.3. Genomic Evolution of Pectobacterium Species—Analysis of Codon and Amino Acid Usage

3.4. Analysis of the Pangenome and Coregenome

3.5. Versatile Pathogenicity Mechanisms have been Acquired Through Integration of Genomic Islands (GIs) Across the Pectobacterium Species

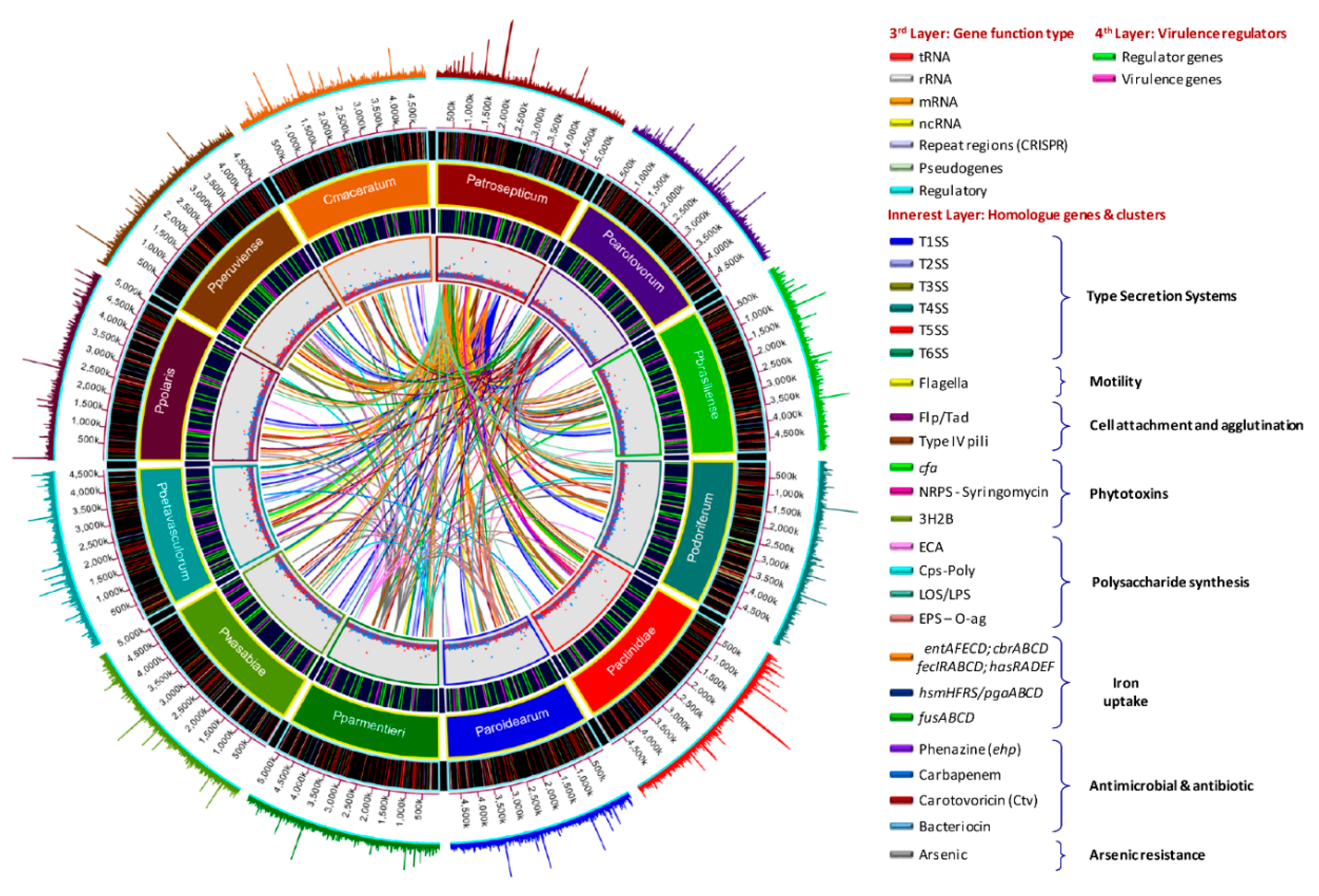

3.6. Genome-Wide Comparison of Gene Clusters Associated with Pathogenesis

3.7. Type Secretion Systems

3.8. Pilin Clusters and Attachment Mechanisms

3.9. Production of Phytotoxins

3.10. Arsenic Resistance is an Intrinsic Feature of Few Species

3.11. Polysaccharide Clusters

3.12. Different Iron Piracy Strategies

3.13. Other Crucial Virulence Determinants

3.14. Virulence Mechanism in Pectobacterium Species Appears to be Regulated by Several Factors

3.15. Diverse Antimicrobial Compounds Secreted by Pectobacterium Species

3.16. A unique Phosphotransferase System (PTS) Cluster Conserved in P. parmentieri

3.17. Pectobacterium Species Harbor Different CRISPR-Cas Systems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Czajkowski, R.; Pérombelon, M.C.M.; van Veen, J.A.; van der Wolf, J.M. Control of blackleg and tuber soft rot of potato caused by Pectobacterium and Dickeya species: A review. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.R.; Kariola, T.; Niemi, O.; Palva, T. Pathogenicity of and plant immunity to soft rot pectobacteria. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, I.K.; Bell, K.S.; Holeva, M.C.; Birch, P.R.J. Soft rot erwiniae: From genes to genomes. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003, 4, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Hibbing, M.E.; Kim, H.-S.; Reedy, R.M.; Yedidia, I.; Breuer, J.; Breuer, J.; Glasner, J.D.; Perna, N.T.; Kelman, A.; et al. Host range and molecular phylogenies of the soft rot enterobacterial genera Pectobacterium and Dickeya. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, F.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Dai, X. Progress of potato staple food research and industry development in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 2924–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhan, S.; Boer, S.H.; Maiss, E.; Wydra, K. Taxonomic relatedness between Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum, Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. odoriferum and Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. brasiliense subsp. nov. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasner, J.D.; Marquez-Villavicencio, M.; Kim, H.-S.; Jahn, C.E.; Ma, B.; Biehl, B.S.; Rissman, A.I.; Mole, B.; Yi, X.; Yang, C.-H.; et al. Niche-specificity and the variable fraction of the Pectobacterium pan-genome. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, A.; Tzou, P.; Lemaitre, B.; Boccard, F. A single gene that promotes interaction of a phytopathogenic bacterium with its insect vector, Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauben, L.; Moore, E.R.B.; Vauterin, L.; Steenackers, M.; Mergaert, J.; Verdonck, L.; Swings, J. Phylogenetic position of phytopathogens within the Enterobacteriaceae. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 21, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardan, L.; Gouy, C.; Christen, R.; Samson, R. Elevation of three subspecies of Pectobacterium carotovorum to species level: Pectobacterium atrosepticum sp. nov., Pectobacterium betavasculorum sp. nov. and Pectobacterium wasabiae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, V.; De Boer, S.H.; Ward, L.J.; Oliveira, A.M.R. Characterization of atypical Erwinia carotovora strains causing blackleg of potato in Brazil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 96, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, R.; Legendre, J.B.; Christen, R.; Saux, M.F.-L.; Achouak, W.; Gardan, L. Transfer of Pectobacterium chrysanthemi (Burkholder et al. 1953) Brenner et al. 1973 and Brenneria paradisiaca to the genus Dickeya gen. nov. as Dickeya chrysanthemi comb. nov. and Dickeya paradisiaca comb. nov. and delineation of four novel species, Dickeya dadantii sp. nov., Dickeya dianthicola sp. nov., Dickeya dieffenbachiae sp. nov. and Dickeya zeae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brady, C.L.; Cleenwerck, I.; Venter, S.N.; Engelbeen, K.; De Vos, P.; Coutinho, T.A. Emended description of the genus Pantoea, description of four species from human clinical samples, Pantoea septica sp. nov., Pantoea eucrina sp. nov., Pantoea brenneri sp. nov. and Pantoea conspicua sp. nov., and transfer of Pectobacterium cypripedii (Hori 1911) Brenner et al. 1973 emend. Hauben et al. 1998 to the genus as Pantoea cypripedii comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2430–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, Y.J.; Kim, G.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Sohn, S.H.; Koh, H.S.; Kwon, S.; Heu, S.; Jung, J.S. Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. actinidiae subsp. nov., a new bacterial pathogen causing canker-like symptoms in yellow kiwifruit, Actinidia chinensis. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2012, 40, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Nabhan, S.; De Boer, S.H.; Maiss, E.; Wydra, K. Pectobacterium aroidearum sp. nov., a soft rot pathogen with preference for monocotyledonous plants. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2520–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayi, S.; Cigna, J.; Chong, T.M.; Quêtu-Laurent, A.; Chan, K.-G.; Hélias, V.; Faure, D. Transfer of the potato plant isolates of Pectobacterium wasabiae to Pectobacterium parmentieri sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5379–5383. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, M.W.; Lysøe, E.; Rossmann, S.; Perminow, J.; Brurberg, M.B. Pectobacterium polaris sp. nov., isolated from potato (Solanum tuberosum). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 5222–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleron, M.; Misztak, A.; Waleron, M.; Franczuk, M.; Wielgomas, B.; Waleron, K. Transfer of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum strains isolated from potatoes grown at high altitudes to Pectobacterium peruviense sp. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirshikov, F.V.; Korzhenkov, A.A.; Miroshnikov, K.K.; Kabanova, A.P.; Barannik, A.P.; Ignatov, A.N.; Miroshnikov, K.A. Draft genome sequences of new genomospecies “Candidatus Pectobacterium maceratum” Strains, Which Cause Soft Rot in Plants. Genome Announc. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.S.; Sebaihia, M.; Pritchard, L.; Holden, M.T.G.; Hyman, L.J.; Holeva, M.C.; Thomson, N.R.; Bentley, S.D.; Churcher, L.J.C.; Mungall, K.; et al. Genome sequence of the enterobacterial phytopathogen Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica and characterization of virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11105–11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkowski, A.O.; Lind, J.; Rubio-Salazar, I. Genomics of plant-associated bacteria: The soft rot Enterobacteriaceae. In Genomics of Plant-Associated Bacteria; Gross, D.C., Lichens-Park, A., Kole, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.H.; Lim, J.-A.; Lee, J.; Roh, E.; Jung, K.; Choi, M.; Oh, C.; Ryu, S.; Yun, J.; Heu, S. Characterization of genes required for the pathogenicity of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum Pcc21 in Chinese cabbage. Microbiology 2013, 159, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Guan, T.; Liu, L.; Yu, S. Bioinformatic analysis of the complete genome sequence of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. brasiliense BZA12 and candidate effector screening. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleron, M.; Waleron, K.; Lojkowska, E. Characterization of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. odoriferum causing soft rot of stored vegetables. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 139, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykyri, J.; Niemi, O.; Koskinen, P.; Nokso-Koivisto, J.; Pasanen, M.; Broberg, M.; Plyusnin, I.; Törönen, P.; Holm, L.; Pirhonen, M.; et al. Revised phylogeny and novel horizontally acquired virulence determinants of the model soft rot phytopathogen Pectobacterium wasabiae SCC3193. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, I.K.; Pritchard, L.; Birch, P.R.J. Comparative genomics reveals what makes an enterobacterial plant pathogen. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 305–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, S.J.; Sebaihia, M.; Porter, L.E.; Stewart, G.S.; Williams, P.; Bycroft, B.W.; Salmond, G.P.C. Analysis of bacterial carbapenem antibiotic production genes reveals a novel β-lactam biosynthesis pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 22, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, D.; Chien, Y.; Wu, H.-P. Cloning and expression of the Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora gene encoding the low-molecular-weight bacteriocin Carocin S1. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.; Wu, H.-P.; Chuang, D. Extracellular secretion of Carocin S1 in Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum occurs via the type III secretion system integral to the bacterial flagellum. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.H.; Tomita, T.; Hirota, M.; Sato, T.; Kamio, Y. A simple purification method and morphology and component analyses for carotovoricin Er, a phage-tail-like bacteriocin from the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora Er. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999, 63, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Izaki, K.; Takahashi, H. Purification and characterization of a bacteriocin from Erwinia carotovora. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1978, 24, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.-H.; Choi, B.-S.; Choi, A.-Y.; Choi, I.-Y.; Heu, S.; Park, B.-S. Genome sequence of pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum strain pcc21, a pathogen causing soft rot in Chinese cabbage. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6345–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemi, O.; Laine, P.; Koskinen, P.; Pasanen, M.; Pennanen, V.; Harjunpää, H.; Nykyri, J.; Holm, L.; Paulin, L.; Auvinen, P.; et al. Genome sequence of the model plant pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum SCC1. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2017, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Bai, Y.; Guo, C. Comparative genomics of 151 plant-associated bacteria reveal putative mechanisms underlying specific interactions between bacteria and plant hosts. Genes Genom. 2018, 40, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, P.R.; Richardson, E.J.; Fitzgerald, J.R. High-throughput sequencing for the study of bacterial pathogen biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 19, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, J.; Wang, N. Where are we going with genomics in plant pathogenic bacteria? Genomics 2019, 111, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klosterman, S.J.; Rollins, J.R.; Sudarshana, M.R.; Vinatzer, B.A. Disease management in the genomics era—summaries of focus issue papers. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1068–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellieny-Rabelo, D.; Tanui, C.K.; Miguel, N.; Kwenda, S.; Shyntum, D.Y.; Moleleki, L.N. Transcriptome and comparative genomics analyses reveal new functional insights on key determinants of pathogenesis and interbacterial competition in Pectobacterium and Dickeya spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Oliver Glöckner, F.; Peplies, J. JSpeciesWS: A web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auch, A.F.; von Jan, M.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2010, 2, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: A multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinform. 2004, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattam, A.R.; Abraham, D.; Dalay, O.; Disz, T.L.; Driscoll, T.; Gabbard, J.L.; Gillespie, J.J.; Gough, R.; Hix, D.; Kenyon, R.; et al. PATRIC, the bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wattam, A.R.; Davis, J.J.; Assaf, R.; Boisvert, S.; Brettin, T.; Bun, C.; Conrad, N.; Dietrich, E.M.; Disz, T.; Gabbard, J.L.; et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesth, T.; Lagesen, K.; Acar, Ö.; Ussery, D. CMG-Biotools, a free workbench for basic comparative microbial genomics. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhan, N.-F.; Petty, N.K.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Beatson, S.A. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): Simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussery, D.W.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Borini, S. Computing for Comparative Microbial Genomics: Bioinformatics for Microbiologists; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli, C.; Laird, M.R.; Williams, K.P.; Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group; Lau, B.Y.; Hoad, G.; Winsor, G.L.; Brinkman, F.S. IslandViewer 4: Expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelli, C.; Brinkman, F.S.L. Improved genomic island predictions with IslandPath-DIMOB. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langille, M.G.; Hsiao, W.W.; Brinkman, F.S. Evaluation of genomic island predictors using a comparative genomics approach. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hudson, C.M.; Lau, B.Y.; Williams, K.P. Islander: A database of precisely mapped genomic islands in tRNA and tmRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Wolf, T.; Chevrette, M.G.; Lu, X.; Schwalen, C.J.; Kautsar, S.A.; Suarez Duran, H.G.; de los Santos, E.L.C.; Kim, H.U.; Nave, M.; et al. AntiSMASH 4.0—Improvements in chemistry prediction and gene cluster boundary identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Heel, A.J.; de Jong, A.; Song, C.; Viel, J.H.; Kok, J.; Kuipers, O.P. BAGEL4: A user-friendly web server to thoroughly mine RiPPs and bacteriocins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.; Petty, N.K.; Beatson, S.A. Easyfig: A genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1009–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvin, D.; Bernheim, A.; Toffano-Nioche, C.; Touchon, M.; Michalik, J.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Vergnaud, G.; Gautheret, D.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of CRISRFinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswas, A.; Staals, R.H.J.; Morales, S.E.; Fineran, P.C.; Brown, C.M. CRISPRDetect: A flexible algorithm to define CRISPR arrays. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uddin, A. Codon Usage Bias: A tool for understanding molecular evolution. J. Proteom. Bioinform. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, P.; Bertrand, C.; Pédron, J.; Barny, M.-A. Draft genomes of “Pectobacterium peruviense” strains isolated from fresh water in France. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2018, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkowski, A.; Blanco, C.; Condemine, G.; Expert, D.; Franza, T.; Hayes, C.; Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N.; Solanilla, E.L.; Low, D.; Moleleki, L.; et al. The role of secretion systems and small molecules in soft-rot Enterobacteriaceae pathogenicity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2012, 50, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Itoh, Y.; Izaki, K.; Takahashi, H. Simultaneous synthesis of pectin lyase and carotovoricin induced by mitomycin c, nalidixic acid or ultraviolet light irradiation in Erwinia carotovora. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1980, 44, 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Hirota, M.; Niimi, Y.; Nguyen, H.A.; Takahara, Y.; Kamio, Y.; Kaneko, J. Nucleotide sequences and organization of the genes for carotovoricin (Ctv) from Erwinia carotovora indicate that Ctv evolved from the same ancestor as Salmonella typhi prophage. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 2236–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chan, Y.-C.; Wu, J.-L.; Wu, H.-P.; Tzeng, K.-C.; Chuang, D.-Y. Cloning, purification, and functional characterization of Carocin S2, a ribonuclease bacteriocin produced by Pectobacterium carotovorum. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roh, E.; Park, T.-H.; Kim, M.-I.; Lee, S.; Ryu, S.; Oh, C.-S.; Rhee, S.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, B.-S.; Heu, S. Characterization of a new bacteriocin, Carocin D, from Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum Pcc21. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7541–7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delepelaire, P. Type I secretion in gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2004, 1694, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Mendoza, D.; Coulthurst, S.J.; Humphris, S.; Campbell, E.; Welch, M.; Toth, I.K.; Salmond, G.P.C. A multi-repeat adhesin of the phytopathogen, Pectobacterium atrosepticum, is secreted by a Type I pathway and is subject to complex regulation involving a non-canonical diguanylate cyclase: Complex regulation of a Pectobacterium type I-secreted adhesin. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, G.; Rajeshwari, R.; Sonti, R.V. Bacterial type two secretion system secreted proteins: Double-edged swords for plant pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douzi, B.; Filloux, A.; Voulhoux, R. On the path to uncover the bacterial type II secretion system. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2012, 367, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Christie, P.J.; Whitaker, N.; González-Rivera, C. Mechanism and structure of the bacterial type IV secretion systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 1578–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trokter, M.; Waksman, G. Translocation through the conjugative type IV secretion system requires unfolding of its protein substrate. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Ulsen, P.; ur Rahman, S.; Jong, W.S.P.; Daleke-Schermerhorn, M.H.; Luirink, J. Type V secretion: From biogenesis to biotechnology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 1592–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernard, C.S.; Brunet, Y.R.; Gavioli, M.; Lloubes, R.; Cascales, E. Regulation of type VI secretion gene clusters by 54 and cognate enhancer binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2158–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pukatzki, S.; Ma, A.T.; Sturtevant, D.; Krastins, B.; Sarracino, D.; Nelson, W.C.; Heidelberg, J.F.; Mekalanos, J.J. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattinen, L.; Nissinen, R.; Riipi, T.; Kalkkinen, N.; Pirhonen, M. Host-extract induced changes in the secretome of the plant pathogenic bacterium Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Proteomics 2007, 7, 3527–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianfanelli, F.R.; Alcoforado Diniz, J.; Guo, M.; De Cesare, V.; Trost, M.; Coulthurst, S.J. VgrG and PAAR proteins define distinct versions of a functional type VI secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattinen, L.; Somervuo, P.; Nykyri, J.; Nissinen, R.; Kouvonen, P.; Corthals, G.; Auvinen, P.; Aittamaa, M.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Pirhonen, M. Microarray profiling of host-extract-induced genes and characterization of the type VI secretion cluster in the potato pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Microbiology 2008, 154, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maier, B.; Wong, G.C.L. How bacteria use type IV pili machinery on surfaces. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Fekih, I.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.P.; Zhao, Y.; Alwathnani, H.A.; Saquib, Q.; Rensing, C.; Cervantes, C. Distribution of arsenic resistance genes in prokaryotes. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosbahi, K.; Wojnowska, M.; Albalat, A.; Walker, D. Bacterial iron acquisition mediated by outer membrane translocation and cleavage of a host protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6840–6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ishimaru, C.A.; Loper, J.E. High-affinity iron uptake systems present in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora include the hydroxamate siderophore aerobactin. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 2993–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Corbett, M.; Virtue, S.; Bell, K.; Birch, P.; Burr, T.; Hyman, L.; Lilley, K.; Poock, S.; Toth, I.; Salmond, G. Identification of a new quorum-sensing-controlled virulence factor in Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica secreted via the type II targeting pathway. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mattinen, L.; Tshuikina, M.; Mäe, A.; Pirhonen, M. Identification and characterization of Nip, Necrosis-inducing virulence protein of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Urbany, C.; Neuhaus, H.E. Citrate uptake into Pectobacterium atrosepticum is critical for bacterial virulence. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, N.; Huang, H.; Meng, K.; Luo, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, P.; Yao, B. Cloning, expression, and characterization of a new phytase from the phytopathogenic bacterium Pectobacterium wasabiae DSMZ 18074. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Welte, C.U.; Rosengarten, J.F.; de Graaf, R.M.; Jetten, M.S.M. SaxA-Mediated isothiocyanate metabolism in phytopathogenic pectobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2372–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, M.; Yang, L.; Yao, P.; Ma, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Qian, G.; Hu, B.; Fan, J. The ribosomal protein RplY is required for Pectobacterium carotovorum virulence and is induced by Zantedeschia elliotiana extract. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pilar Marquez-Villavicencio, M.; Weber, B.; Witherell, R.A.; Willis, D.K.; Charkowski, A.O. The 3-hydroxy-2-butanone pathway is required for Pectobacterium carotovorum pathogenesis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, S.; Sebaihia, M.; Jones, S.; Yu, B.; Bainton, N.; Chan, P.F.; Bycroft, B.; Stewart, G.S.A.B.; Williams, P.; Salmond, G.P.C. Carbapenem antibiotic production in Erwinia carotovora is regulated by CarR, a homologue of the LuxR transcriptional activator. Microbiology 1995, 141, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Haque, M.M.; Oliver, M.M.H.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.Z.; Hirata, H.; Tsuyumu, S. CytR Homolog of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum controls air-liquid biofilm formation by regulating multiple genes involved in cellulose production, c-di-GMP signaling, motility, and type III secretion system in response to nutritional and environmental signals. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parker, W.L.; Rathnum, M.L.; Wells, J.J.S.; Trejo, W.H.; Principe, P.A.; Sykes, R.B. SQ 27, 860, a simple carbapenem produced by species of Serratia and Erwinia. J. Antibiot. 1982, 35, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGowan, S.J.; Sebaihia, M.; O’Leary, S.; Williams, P.; Salmond, G.P.C. Analysis of the carbapenem gene cluster of Erwinia carotovora: Definition of the antibiotic biosynthetic genes and evidence for a novel β-lactam resistance mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrodi, D.V.; Peever, T.L.; Mavrodi, O.V.; Parejko, J.A.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; Mazurier, S.; Heide, L.; Blankenfeldt, W.; Weller, D.M.; et al. Diversity and evolution of the phenazine biosynthesis pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grinter, R.; Milner, J.; Walker, D. Ferredoxin containing bacteriocins suggest a novel mechanism of iron uptake in Pectobacterium spp. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Alkhnbashi, O.S.; Costa, F.; Shah, S.A.; Saunders, S.J.; Barrangou, R.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Charpentier, E.; Haft, D.H.; et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tambong, J.T. Comparative genomics of Clavibacter michiganensis subspecies, pathogens of important agricultural crops. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Monchy, S.; Taghavi, S.; Zhu, W.; Ramos, J.; van der Lelie, D. Comparative genomics and functional analysis of niche-specific adaptation in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozobay-Avraham, L. Involvement of DNA curvature in intergenic regions of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 2316–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duan, C.; Huan, Q.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Carey, L.B.; He, X.; Qian, W. Reduced intrinsic DNA curvature leads to increased mutation rate. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wojcik, E.A.; Brzostek, A.; Bacolla, A.; Mackiewicz, P.; Vasquez, K.M.; Korycka-Machala, M.; Jaworski, A.; Dziadek, J. Direct and inverted repeats elicit genetic instability by both exploiting and eluding DNA double-strand break repair systems in Mycobacteria. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.-S.; Ma, B.; Perna, N.T.; Charkowski, A.O. Phylogeny and virulence of naturally occurring type III secretion system-deficient Pectobacterium strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4539–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.-S.; Thammarat, P.; Lommel, S.A.; Hogan, C.S.; Charkowski, A.O. Pectobacterium carotovorum elicits plant cell death with DspE/F but the P. carotovorum DspE does not suppress callose or induce expression of plant genes early in plant–microbe interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rojas, C.M.; Ham, J.H.; Deng, W.-L.; Doyle, J.J.; Collmer, A. HecA, a member of a class of adhesins produced by diverse pathogenic bacteria, contributes to the attachment, aggregation, epidermal cell killing, and virulence phenotypes of Erwinia chrysanthemi EC16 on Nicotiana clevelandii seedlings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13142–13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poole, S.J.; Diner, E.J.; Aoki, S.K.; Braaten, B.A.; t’Kint de Roodenbeke, C.; Low, D.A.; Hayes, C.S. Identification of functional toxin/immunity genes linked to contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) and rearrangement hotspot (Rhs) systems. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallique, M.; Bouteiller, M.; Merieau, A. The type VI secretion system: A dynamic system for bacterial communication? Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Coulthurst, S.J.; Pritchard, L.; Hedley, P.E.; Ravensdale, M.; Humphris, S.; Burr, T.; Takle, G.; Brurberg, M.-B.; Birch, P.R.J.; et al. Quorum sensing coordinates brute force and stealth modes of infection in the plant pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giltner, C.L.; Nguyen, Y.; Burrows, L.L. Type IV pilin proteins: Versatile molecular modules. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 740–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carbonnelle, E.; Hélaine, S.; Prouvensier, L.; Nassif, X.; Pelicic, V. Type IV pilus biogenesis in Neisseria meningitidis: PilW is involved in a step occurring after pilus assembly, essential for fibre stability and function. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 55, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Tammam, S.; Ku, S.-Y.; Sampaleanu, L.M.; Burrows, L.L.; Howell, P.L. PilF is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for multimerization and localization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus secretin. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 6961–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sauvonnet, N.; Gounon, P.; Pugsley, A.P. PpdD type IV pilin of Escherichia coli K-12 can be assembled into pili in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giltner, C.L.; van Schaik, E.J.; Audette, G.F.; Kao, D.; Hodges, R.S.; Hassett, D.J.; Irvin, R.T. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilin receptor binding domain functions as an adhesin for both biotic and abiotic surfaces. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nykyri, J.; Mattinen, L.; Niemi, O.; Adhikari, S.; Kõiv, V.; Somervuo, P.; Fang, X.; Auvinen, P.; Mäe, A.; Palva, E.T.; et al. Role and regulation of the Flp/Tad pilus in the virulence of Pectobacterium atrosepticum SCRI1043 and Pectobacterium wasabiae SCC3193. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panda, P.; Vanga, B.R.; Lu, A.; Fiers, M.; Fineran, P.C.; Butler, R.; Armstrong, K.; Ronson, C.W.; Pitman, A.R. Pectobacterium atrosepticum and Pectobacterium carotovorum harbor distinct, independently acquired integrative and conjugative elements encoding coronafacic acid that enhance virulence on potato stems. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.L.; N-Chaidez, F.A.; Gross, D.C. Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxins: Mode of action, regulation, and biosynthesis by peptide and polyketide synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 266–292. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, T.J.; Ind, A.; Komitopoulou, E.; Salmond, G.P.C. Phage-selected lipopolysaccharide mutants of Pectobacterium atrosepticum exhibit different impacts on virulence. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ragunath, C.; Shanmugam, M.; Bendaoud, M.; Kaplan, J.B.; Ramasubbu, N. Effect of a biofilm-degrading enzyme from an oral pathogen in transgenic tobacco on the pathogenicity of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinter, R.; Josts, I.; Mosbahi, K.; Roszak, A.W.; Cogdell, R.J.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Milner, J.J.; Kelly, S.M.; Byron, O.; Smith, B.O.; et al. Structure of the bacterial plant-ferredoxin receptor FusA. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinter, R.; Hay, I.D.; Song, J.; Wang, J.; Teng, D.; Dhanesakaran, V.; Wilksch, J.J.; Davies, M.R.; Littler, D.; Beckham, S.A.; et al. FusC, a member of the M16 protease family acquired by bacteria for iron piracy against plants. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pirhonen, M.; Saarilahti, H.; Karlsson, M.-B.; Palva, E.T. Identification of pathogenicity determinants of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora by transposon mutagenesis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991, 4, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, C.L.; Whitehead, N.A.; Sebaihia, M.; Bell, K.S.; Hyman, L.J.; Harris, S.J.; Matlin, A.J.; Robson, N.D.; Birch, P.R.J.; Carr, J.P.; et al. Novel quorum-sensing-controlled genes in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora: Identification of a fungal elicitor homologue in a soft-rotting bacterium. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fitzpatrick, D.A. Lines of evidence for horizontal gene transfer of a phenazine producing operon into multiple bacterial species. J. Mol. Evol. 2009, 68, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Wiebe, R.; Dilay, L.; Thomson, K.; Rubinstein, E.; Hoban, D.J.; Noreddin, A.M.; Karlowsky, J.A. Comparative review of the carbapenems. Drugs 2007, 67, 1027–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lin, T.-L.; Hsieh, P.-F.; Wang, J.-T. Cellobiose-specific phosphotransferase system of Klebsiella pneumoniae and its importance in biofilm formation and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Yoo, B.B.; Hwang, C.-A.; Suo, Y.; Sheen, S.; Khosravi, P.; Huang, L. LMOf2365_0442 encoding for a fructose specific PTS permease IIA may be required for virulence in L. monocytogenes Strain F2365. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Makarova, K.S.; Zhang, F. Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 37, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, D.; Amlinger, L.; Rath, A.; Lundgren, M. The CRISPR-Cas immune system: Biology, mechanisms and applications. Biochimie 2015, 117, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godde, J.S.; Bickerton, A. The repetitive DNA elements called CRISPRs and their associated genes: Evidence of horizontal transfer among prokaryotes. J. Mol. Evol. 2006, 62, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seed, K.D.; Lazinski, D.W.; Calderwood, S.B.; Camilli, A. A bacteriophage encodes its own CRISPR/Cas adaptive response to evade host innate immunity. Nature 2013, 494, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, B.N.J.; Staals, R.H.J.; Fineran, P.C. CRISPR-Cas-Mediated phage resistance enhances horizontal gene transfer by transduction. mBio 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koonin, E.V.; Makarova, K.S. CRISPR-Cas: Evolution of an RNA-based adaptive immunity system in prokaryotes. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Doak, T.G.; Ye, Y. Expanding the catalog of cas genes with metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 2448–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbate, M.; Orata, F.D.; Petty, N.K.; Jayatilleke, N.D.; King, W.L.; Kirchberger, P.C.; Allen, C.; Mann, G.; Mutreja, A.; Thomson, N.R.; et al. A genomic island in Vibrio cholerae with VPI-1 site-specific recombination characteristics contains CRISPR-Cas and type VI secretion modules. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haft, D.H.; Selengut, J.; Mongodin, E.F.; Nelson, K.E. A guild of 45 CRISPR-associated (cas) protein families and multiple CRISPR/Cas subtypes exist in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2005, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, Y. Not all predicted CRISPR–Cas systems are equal: Isolated cas genes and classes of CRISPR like elements. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Genome Features | Pectobacterium species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pa | P. carotovorum subspecies | Par | Pp | Pw | Pb † | Ppo | Ppe † | Cpm † | ||||

| Pcc | Pcb | Pco | Pca † | |||||||||

| Length (bp) | 5,064,019 | 4,842,771 | 4,920,350 | 4,933,575 | 4,922,167 | 4,862,913 | 5,164,411 | 5,043,228 | 4,685,210 | 5,008,416 | 4,785,880 | 4,993,011 |

| % GC | 51 | 52.2 | 51.84 | 51.75 | 51.54 | 51.9 | 50.4 | 50.55 | 51.2 | 51.99 | 51.1 | 51.82 |

| CDS (coding) | 4381 | 4115 | 4267 | 3855 | 4151 | 4232 | 4449 | 4416 | 4070 | 4301 | 4158 | 4338 |

| Proteins with EC number appointed * | 1107 | 1078 | 1082 | 1103 | 1111 | 1094 | 1113 | 1089 | 1078 | 1113 | 1143 | 1123 |

| Proteins involved in metabolic pathways * | 829 | 799 | 806 | 814 | 828 | 813 | 835 | 805 | 802 | 813 | 835 | 813 |

| rRNAs (5S, 16S, 23S) | 8, 7, 7 | 8, 7, 7 | 8, 7, 7 | 8, 7, 7 | 7, 7, 7 | 8, 7, 7 | 8, 7, 7 | 8, 7, 7 | 7, 8, 1 | 8, 7, 7 | 2, 1, 2 | 8, 8, 3 |

| tRNAs | 77 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 76 | 78 | 77 | 77 | 71 | 77 | 66 | 70 |

| ncRNAs | 10 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Pseudogenes | 125 | 121 | 97 | 385 | 103 | 53 | 286 | 184 | 200 | 116 | 106 | 107 |

| Virulence factor * | 48 | 46 | 47 | 50 | 50 | 47 | 53 | 48 | 43 | 46 | 52 | 47 |

| Antibiotic resistance * | 60 | 54 | 56 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 54 | 57 | 45 | 56 | 60 | 56 |

| Drug target [TTD] * | 29 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 35 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arizala, D.; Arif, M. Genome-Wide Analyses Revealed Remarkable Heterogeneity in Pathogenicity Determinants, Antimicrobial Compounds, and CRISPR-Cas Systems of Complex Phytopathogenic Genus Pectobacterium. Pathogens 2019, 8, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8040247

Arizala D, Arif M. Genome-Wide Analyses Revealed Remarkable Heterogeneity in Pathogenicity Determinants, Antimicrobial Compounds, and CRISPR-Cas Systems of Complex Phytopathogenic Genus Pectobacterium. Pathogens. 2019; 8(4):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8040247

Chicago/Turabian StyleArizala, Dario, and Mohammad Arif. 2019. "Genome-Wide Analyses Revealed Remarkable Heterogeneity in Pathogenicity Determinants, Antimicrobial Compounds, and CRISPR-Cas Systems of Complex Phytopathogenic Genus Pectobacterium" Pathogens 8, no. 4: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8040247