1. Introduction

Recently, the scientific and medical communities have come under scrutiny for their failures to quickly and effectively rebuke senior researchers who have been found guilty of sexual assault and sexual harassment [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In several cases the offenders were revealed to be serial offenders, and in some instances were able to continue their research at other institutions after being adjudicated. Researchers also have been found to have falsified or otherwise manipulated data—and significant professional and personal repercussions ensued, in some cases with a tragic ending for the researcher [

5]. The primary premise of this paper is that a number of researchers who have been found guilty of misconduct have been afforded considerable leeway to continue harassing students and staff at other institutions or in other roles; this luxury is not given to those who were harassed, and who are disproportionately junior staff or trainees [

6,

7]. The goal of the manuscript is to draw the attention of professional societies to the challenge at hand and to determine how to protect the community, in particular trainees and traditionally underrepresented or otherwise marginalized persons.

Of course, the simplest and most straightforward approach is for perpetrators to stop immediately, and of their own accord—something many societies have tried, and which has failed. In addition to consistent, appropriate sanctions against perpetrators, broad-spectrum changes within an ethical framework are needed to ensure the integrity of our researchers and research processes. As outlined previously, what is really need are changes to policy [

8]. Professional societies, which are not bound by the same constraints as employers, can use an Ethical Code of Conduct that provides for professional (rather than exclusively legal) ramifications; it is critical that the self-regulation of professional societies is not only figurative [

9]. Membership in most professional societies is already framed as a privilege, rather than a right, and the integrity of those institutions can be greater than the individual institutions their members represent. Codes of conduct can also be used to reinforce constructive behaviors and outline expectations, which is increasingly relevant with a multicultural membership.

Codes of conduct are being developed and implemented across a variety of circumstances, from undergraduate courses [

10] to college and university presidents [

11]. So if other relevant codes apply, why should professional societies have their own?

Aristotle has been called the first business ethicist, as well as the first economist [

12]. By thinking of the good of the wider community, rather than just of personal gain, individuals create value through social enterprise. For evidence of this you need look no further than the postdoctoral training period, a stalwart of many disciplines [

13]. Further, the Aristotelian approach which equally weights individuals making ethical decisions and corporations (or professional societies) making ethical decisions demonstrates the need for an individual Honor Code that’s supported by the robust framework of a professional code of conduct.

Using a virtue-based theoretical framework to understand the work done by nonprofit and professional societies can be useful. Ethical conduct incorporates how we perform our research, how we mentor the next generation of practitioners, and how we interact with our peers. The concept of peer-review, as a volunteer contribution that is required of “good citizenship” in the field, is the basis for research communities and should be seen as a component of the behavioral ethics of an organization [

14]. Moral awareness may be the first stage of the ethical decision-making process [

15], but should not be considered the final step [

16]. Research into ethical conduct in the workplace exists, and is current: recent work focuses on defining boundaries between workplace romance and sexual harassment on social media [

17].

However, according to Nussbaum, “It is not helpful to speak of ‘virtue ethics’, and… we would be better off characterizing the substantive views of each thinker—and then figuring out what we ourselves want to say” [

18]. “Virtual remoteness”, where ethical guidelines are divorced from actual experience [

19], lends itself to a relativist idea that individual societies are the only ones able to create ethical guidelines about their own traditions and practices. In the context of professional and scientific societies it is easy to see how this environment helps create an exclusionary syndicate with considerable influence over career outcomes [

20,

21,

22]. Although we do not have the space to fully discuss each thinker in this article, professional societies would do well to determine their approach in the context of previous work (in their discipline and across relevant others) and the relevant sociopolitical environment. Societies should consider what Appiah says succinctly: “What we do depends on how the world is” [

23].

2. Specific Considerations for Professional Societies

Generally, professional societies are made of experts in the field with considerable leadership and expertise involved in the running of the society (either from an outside source such as paid staff or a management company, or elected leaders from within the discipline). This is key for financial and regulatory compliance to retain the nonprofit status of the societies on which the article is focused. For this reason, the gray areas of ethical conduct are generally addressed within the discipline; this paper applies to unethical conduct that is a common thread for professional and scientific societies. The systematic and pervasive challenge, as outlined earlier in this article, is how to address the status of members in professional societies who have committed fundamental misconduct. As some of the types of transgression discussed in this article are illegal, professional societies have an obligation to protect themselves and their constituents from serial misconduct. An effective code of conduct can help provide the framework to enact meaningful change.

Non-profit societies in particular seem to be afflicted with the idea that you must not take a political stance, although really in most countries (including the United States) what they are prevented from doing is lobbying to influence legislation. With this in mind, societies can and should encourage programs to educate the public and prepare and distribute information about public policy issues relevant to their work. This is true for legislation that may have an impact on the diverse workforce the science and medical professions need to be successful into the future.

Although punitive measures are appropriate in some cases, I see the more important role as preventative. Although some incidents may call for permanent action, the path to redemption should be outlined and include probation, re-training, and the right oversight afterwards. Depending on the type of incident, a change of role may also be recommended.

Many codes of conduct stop with awareness about expectations, and offer little in the way of repercussions for serial offenders, informally or formally. Another challenge is the disconnected nature of professional societies, which incorporate individuals across the career stage spectrum, and often provide opportunities for cross-institutional interactions at professional events such as conferences and networking sessions. Currently, the quiet dismissal and subsequent re-hiring of a serial offender creates an environment that feels much like “whack-a-mole”, when more senior stewards in the field are challenged to find new and different ways to subtly indicate unethical conduct by other members of the discipline. This puts trainees, students, and early-career researchers at unnecessary risk, and damages public perception of the discipline when long-term harassers are finally publically acknowledged.

Recent work has shown that corporations with a rigorous corporate code of conduct had a higher public perception of corporate citizenship, sustainability, ethical behavior, as well as higher social responsibility performance [

24]. This is good news for professional organizations and researchers who are on the front foot in this space. In an era when perceived unethical conduct decreases the public’s trust in science and researchers [

25], consensus can help rebuild public trust [

26].

Professional societies have the added advantage of being able to help with career progression for victims of career sabotage. Using the network of professionals, if an incident has been resolved by the ombudsperson, a support network can be tasked with evaluating the person’s needs and current status, and exploring ways to meet those needs. Support could include finding a laboratory to finish the research project in, financial support for a transition to another institute, and access to a network of mentors who will be able to advocate appropriately for career progression and provide letters of reference. As outlined previously, gender balance at conferences [

27] and emphasizing equity in emerging fields [

28] does not just save face—it also helps support the career trajectory and professional network of persons from traditionally underrepresented groups.

Although broadly applicable, the content provided herein is most relevant for nonprofit and professional societies, such as those that represent research scientists (in the physical, life, and social sciences as well as the arts and humanities), medical professionals, and those in the higher education sector. Anyone who has a leadership role in a professional society should be able to use this work as a practical handbook for discussion with the governing board of the organization to enact an appropriate policy.

Previous work provides examples of what elements a code of ethics should contain in order to be seen as effective by users including providing examples, readability, relevance, realism, training, reinforcement, and reporting requirements [

29]. The best codes of conduct are the ones that do not need to be enforced, because the parties are already behaving in an ethical and professional manner. In past case studies, employees report that informal measures such as the “social norms of the organization” have the greatest impact on their conduct [

30].

How does a society determine whether a code of conduct is effective? First, determine the ethical behaviors that should be continued, and incentivize them; second, determine which actions are unethical and should be punished or, ideally, prevented. In some cases an organizational culture analysis has been used to troubleshoot what did not work with previous policies [

31].

3. Case Study: The Royal Australian College of Surgeons

As evidenced by the Royal Australian College of Surgeons (RACS), a code of conduct includes a number of elements. The code of conduct is a commitment fellows make to patients, their field, and to the community. Before a surgeon is admitted to fellowship (indicating their training to become a surgeon is complete), they must recite and continue to abide by a pledge [

32].

RACS Fellowship Pledge [

32]:

I pledge to always act in the best interests of my patients, respecting their autonomy and rights.

I undertake to improve my knowledge and skills, evaluate, and reflect on my performance.

I agree to continue learning and teaching for the benefit of my patients, my trainees and my community.

I will be respectful of my colleagues, and readily offer them my assistance and support.

I will abide by the Code of Conduct of this College, and will never allow considerations of financial reward, career advancement, or reputation to compromise my judgment or the care I provide.

I accept the responsibility and challenge of being a surgeon and a Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

In 2015, a senior woman surgeon was quoted as saying women trainees should “protect their surgical careers by ‘complying with requests’ for sex from male colleagues [as] a safer option than reporting the harassment” [

33].

The public outcry and widespread agreement in the surgical community of an environment of bullying and harassment caused the RACS to commission an independent report by an expert advisory group [

34]. The report found 49% of fellows, trainees, and international medical graduates were subjected to bullying, discrimination, or sexual harassment; 71% of hospitals reported discrimination, bullying, or sexual harassment by a surgeon in their hospital within the last five years.

The RACS accepted the final report from the committee and apologized publically. In response to the report the RACS has been running campaigns promoting ethical conduct and practice (“Let’s Operate with Respect”); and they addressed specific challenges comprehensively with an action plan containing eight targeted goals. The RACS has continued to provide public updates on their progress and on ongoing challenges.

The RACS has created an umbrella approach to their code of conduct, not just a one-size-fits-all single document. They have tailored the punitive and preventative clauses to reflect the reality of their profession, and the needs of their membership. As fellowship in the RACS is a requirement of professional practice, the RACS has effectively tied ethical conduct to professional registration.

4. Define What You Are Talking about

Language is important [

35], and using inclusive language helps demonstrate to members and stakeholders that you are an ethical, equitable professional organization. Further, definitions of what constitutes harassment are not universal [

36]. A key element of creating an inclusive and effective code of conduct is consultation with the community [

37], and particular care should be taken to address the concerns of traditionally underrepresented and otherwise marginalized groups. It will be important to lay the framework for your ethics policy, and I recommend considering the implementation of an Honor Code to put the onus of reporting onto members of the society as well as members and nonmembers who observe harm being done. When you operate from an Honor Code, the burden of reporting unethical behavior is then moved solely from the victim onto the supportive scaffolding of a professional network.

What can be covered? In this article, I refer both to illegal activity (sexual assault and sexual harassment; threats or actual physical violence; discriminatory harassment), and to unethical conduct (data fabrication, data manipulation, and plagiarism). Sexual assault and harassment in the research environment should be considered broadly as they may have different repercussions for students, trainees, and staff. The policy should address other types of discrimination, including (but not limited to) race, ethnicity, gender identity, gender presentation, sex, sexual preference, status as a parent or caregiver, socioeconomic status, disability status, country of origin, and the intersections of those perspectives, as well as physical or verbal harassment and assault. For the remainder of this article for the sake of clarity, I will class all these as elements of “career sabotage”, since the outcome we are trying to avoid is persons leaving higher education, training, or careers in our disciplines.

This paper is focused on unethical conduct, which includes illegal activity (in the cases of physical, sexual, or discriminatory harassment) as well as data manipulation and other field-specific concerns. In some fields, it is difficult or less straightforward to determine whether data has been manipulated, for example. Research is conducted in a number of different disciplines, so recognizing this complexity is valuable for individual societies. In order to establish an appropriate code of conduct for a professional society, this ambiguity should be addressed so it does not appear that varied or that less permanent consequences are a reflection of a less ethical society.

As appropriate, consult a legal professional who can provide advice on your specific situation and the type of language that ought to be used. Professional societies may wish to engage a solicitor to review the policy before implementation, to ensure you are in compliance with government regulations and directives from funding bodies.

5. Determine Who Is Affected

This will include who is covered by your policy, and also try to support the persons who are most at risk of finding themselves subject to ethical breaches.

Will your policy aim to cover all members of your professional society, only registered professionals, or anyone working in that space? Will students and trainees be covered, and if so how?

Are there certain groups of people who are traditionally underrepresented in your discipline specifically who would benefit from institutionalized support? Survey your members, and see what their needs are. A member survey may also help to recruit persons to serve in the new roles that will be created, and to find other areas of overlap where additional oversight from the society is indicated.

6. Assign Responsibility

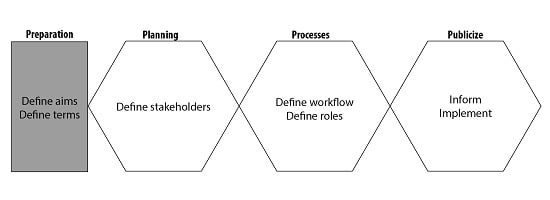

A key feature of any initiative is determining (1) who is responsible for drafting, reviewing, and approving the policy; (2) who is responsible for implementation, administration, and reporting; and, (3) who is responsible for administering the decisions being handed down. Ideally, there will be three independent working groups to spread the workload and maintain the integrity of the process.

7. Build a Reporting Structure

How will the privacy and confidentiality of all involved parties be maintained? Will the form be online or a downloadable form? How will submission work? What evidence will be required to report an incident? These are some of the questions that should be addressed by the committee designated to draw up the policy.

When the incident goes before a committee for adjudication, it should be anonymized where possible (e.g., using member identification numbers or similar). The Ombudsperson or an independent entity would have access to identifying information, and in those cases it should be used to determine whether an offender has come before the committee previously, to obliterate the potential for known unethical behavior to continue for decades unchecked.

8. Define the Committee

A committee should consist of a number of representatives across the spectrum of persons you wish to represent (see

Section 5). Particular effort should be made to recruit committee members from traditionally underrepresented groups (see

Section 4). Students and trainees should sit on the committee as well, perhaps as nonvoting members, to gain experience in the ethical conduct and expectations of the profession.

9. Emphasize and Maintain Confidentiality

Appropriate protections should be in place to maintain the confidentiality of the victim, perpetrator, and individuals who sit on the committee. All queries should go to a central email address (e.g.,

[email protected]) rather than an individual’s personal email address to ensure continuity, and to protect both the identity of the victim or whistleblower and the accused.

Rather than having a single person responsible for adjudicating incidents, a committee of seven with staggered terms of three years (for example) will help ensure all sides are considered equally and can help to ensure repercussions are fair and consistent. The committee would include the Ombudsperson as Chair, and six voting members; the Chair would be nonvoting, except to break a tie. The Ombudsperson would also be responsible for determining what sanctions, if any, are indicated, and can evaluate progress made after any rehabilitative steps are taken (such as approved training courses, or the addition of mentors for the accuser to ensure career progression can be made).

10. Outline Consistent Outcomes

Generally, by joining the professional society as members, individuals agree to the terms and conditions set forth by the governing body. The society should retain the right to revoke membership at any time, without cause, perhaps subject to adjudication or appeal to the Ombudsperson. The policy should be applicable to all members equally, regardless of age, tenure status, or other confounding factors. The policy should take care to emphasize that these are not legal proceedings and confidentiality is a key consideration.

John Foubert, former Assistant Dean of Students at the University of Virginia, explained his opinion about how most universities currently handle rape cases: “Mediation is not appropriate when we’re talking about a felony” [

38]. It is true: felonies, such as rape and hate crimes, are outside the remit of most professional societies, and mediation is not an appropriate strategy. However, that does not entitle us to inertia when members of our community are being victimized.

Repercussions could be structured as a “three strikes and out” rule for membership, for repeat offenders; a ban from attending or presenting at society conferences; a ban from applying for funding of any kind from the professional society; a ban on publishing in society journals; a ban on membership in the society; and others, as appropriate. Since membership is a privilege that can be revoked any time, all these are fair uses of the society’s self-regulation, but the terms and conditions of a professional society could easily be amended to include adherence to the code of conduct and generally ethical behavior as a requirement of membership.

For additional professional repercussions, individual societies should have a pathway for how they would prevent serial offenders from simply changing roles or institutions to continue their unethical behavior, as has happened in the recent past. Department heads could opt-in for a notification by running their job candidates past the Ombudsperson, and a brief, anonymized report of any incidents investigated and adjudicated, as well as recommended outcomes, could be provided. An obvious red flag would be checking the candidate’s membership status in the most appropriate professional society, and if they are not a member in good standing, further explanation could be requested.

11. Use an Impartial Ombudsperson

It is critical that the policy is seen as being implemented effectively and consistently. Societies may wish to have agreements with each other, whereby each would provide an Ombudsperson for the other, to avoid potential conflicts of interest personally or professionally. Appropriate training to maintain confidentiality and to enable appropriate, consistent repercussions would be key, and the Ombudsperson should report directly to the governing board. Should an institute inquire about why a professional’s membership has been revoked, if it is due to adjudication, an appropriate response will be provided by the Ombudsperson while taking care to maintain confidentiality as appropriate.

The Ombudsperson would also be responsible for liaising with the appropriate authorities for felonies or similar crimes when those cases fall outside the remit of the professional society to address, when the victim wishes to do so. The Ombudsperson should be willing to provide evidence as requested by law enforcement as it relates to individual cases.

12. Publicize the Policy

Share the policy and how it will be implemented with your stakeholders: not just through members, but industry and government partners. Make it a regular feature in the newsletter. Create a dedicated section of the website with information and resources that can be accessed anonymously (at least some information should be available outside a members-only area). Ask that conference attendees agree to the terms during conference registration, and print the policy and how to report transgressions in the conference program book, and make the information available on the conference website in a place that is easily accessible. Provide training and resources for volunteers who want to help ensure meeting attendees are safe, as has been done by professionals in astronomy (Astro Allies <

www.astronomyallies.com>) and entomology (Ento Allies <

https://entoallies.org>). Ensure people feel supported by the policy and encouraged to use it when appropriate.

13. Actually Implement the Policy

Additionally, report the outcomes. Better yet, rather than waiting for victims to come forward, use an annual survey for your membership to audit the professional environment [

39]. The survey can ask whether someone has experienced unethical conduct around those axes (sexual violence, race, ethnicity, gender, disability, as well as others as appropriate to your membership) in the last 12 months in their professional capacity. Ask whether they would like the Ombudsperson to follow up with them individually about their experience. Share the survey results, and use the data to subsequently refine the policy and guide appropriate action. As appropriate, re-education through compulsory or volunteer training programs and member updates can help ensure the guidelines are shared throughout the whole community, and that individuals and supervisors know their rights and responsibilities with respect to reporting.

14. Discussion

We need all hands on deck to address the world’s problems. The best minds should be doing the work, uncompromised by unethical or unprofessional behavior.

It will likely never be financially straightforward for a society to implement an appropriate code of conduct that has clear, enforceable repercussions. Many professional societies are small nonprofits with limited resources, and their reluctance to wade into legally murky waters on this front is understandable. However, this is a moral issue. It is a matter of ethical conduct with respect to data fabrication, harassment, and the diversity of our disciplines. Traditionally underrepresented groups already face hardship when advocating for themselves for promotion and hiring [

40,

41,

42], and to accept the status quo on this front is unethical of professional societies.

Creating an ethical culture of corporate responsibility takes an interdisciplinary effort [

43]. A key recent shift has been in the use of social media, which employees use to communicate both at work and about work [

44]. The “Ethic of Futurity” [

45], which posits the method of communication between a corporation and its stakeholders should be aligned with the anticipated outcomes of the corporation’s actions on stakeholders, presents a useful model for communication within a professional society. This model places the emphasis not only on the content, but on the method of communication and the way the dialog is created and led. Communication and how content is perceived has specific repercussions for the reputation of an organization as ethical [

46]. In an age where evidence-based information is increasingly reliant on its public image and the image of its experts, an ethical code of conduct is a critical component of credibility.

The need to find appropriate ways to measure ethical behavior, depending on the field, has been comprehensively explored [

47]. One notable example is efforts in the 1990s to boost productivity in automotive repair shop employees by putting shop employees on a commission- and quota-based system, which caused the employees to perform unnecessary repairs to increase their apparent workload. This environment of having to quantify each transaction has parallels with the current research environment, where there are imperfect metrics such as impact factor, h-index, and the number of citations a paper receives [

48,

49,

50]. It should be noted these metrics do not capture the public impact of a new finding, which may be better suited to altmetrics [

51,

52,

53].

Career sabotage causes some of our most promising contributors lasting hardship, and leads many to rethink their career trajectory. We need all our best minds working together to solve current and future challenges, and unnecessary disturbances such as harassment and assault have no place in professional organizations. Ethical conduct should be the order of the day for professionals. We should demonstrate to the public and other stakeholders that we are responsible stewards of young minds, and that taxpayer dollars are funding principled researchers and projects.

Sexual harassment has been shown to be particularly pervasive and damaging in academic contexts [

7,

54]. For those who are disproportionately concerned about the inconvenience or career damage caused to individuals who break the code of professional conduct, consider that the rate of these occurrences is likely similar to what it is in the general public, if not lower. Recent reports show a false report rate of less than 3% in Australia [

55] and the United Kingdom [

56] for rape, figures that are approximately consistent with figures from federal reporting agencies in other countries. Careful listening to those who report is of the utmost importance [

57].

Serial offenders exist because we continue to offer them what they need most: anonymity and silence. Confirmed violations of Title IX or other internal disciplinary procedures are not reported widely, and often offenders are allowed to leave the institution quietly to prevent a public discussion of what can be a very private matter. “New” media outlets in particular, most notably BuzzFeed, have extensively and accurately reported on the sexual harassment and unethical conduct of academic and other professionals. These media outlets protect the identity of the accuser, unless the person wishes to self-identify, so concerns about the privacy of the victim are generally a straw man argument. The anonymity once afforded offenders is rapidly disappearing, and the time is right to make our policies stronger to protect the integrity of our disciplines.

While respecting the boundaries of confidentiality and the wishes of the reporting individual, it is essential that offenders are not allowed to continue their bad behavior elsewhere unchecked, and it is unethical to continue to place trainees in danger as we have done in the past. While considering the possibility of redemption and that offenders may be able to be rehabilitated with appropriate training, the creation of a mechanism to track offenders who have been found to be unethical (and the subsequent consequences and training completed) would be useful to those responsible for hiring and for the supervision of students and trainees. Most individuals in senior roles want to protect their students and staff, and in many cases are simply unaware of past transgressions.

This is where professional societies, which aim to protect and promote the discipline across institutional and geographic boundaries, can play a pivotal role. Serial offenders could be prevented from attending society-run meetings, publishing in society journals, and from participating in society-sponsored training and networking sessions. Most codes of conduct could be amended to include a line about membership being an honor, not a right, and reminding members that anyone found to be participating in unethical conduct will be unable to maintain their membership. Thus, it could serve as a red flag for search committees if a candidate is not a member of the most widely joined professional society for a particular field, and a potential area of further inquiry.

15. Conclusions

These guidelines are generally written for professional societies, but everyone can make a contribution. How can an individual help? Proactively conduct a pay audit in the space you manage to make sure everyone doing the same job is being paid the same. When an award crosses your desk, find underrepresented excellence—and help with the nomination. Encourage your professional societies to develop and implement an ethics policy; be a supporter of the Ombudsperson role. See where your skills are, and offer to help: perhaps you could help design the new ethics webpage, or write a newsletter communicating the outcomes, or use your network to help recruit persons for the various roles. Make your institute or organizational unit a welcome space for excellence, no matter what the situation the person is joining you has experienced. Take individuals who report unethical conduct at their word, and do not place an undue burden of proof on those reporting, but ensure an impartial and rigorous investigation takes place.

It is a privilege and a responsibility to be a part of a professional society, and it is time we remind leaders and members of their duties and obligations.