The α1 Antagonist Doxazosin Alters the Behavioral Effects of Cocaine in Rats

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

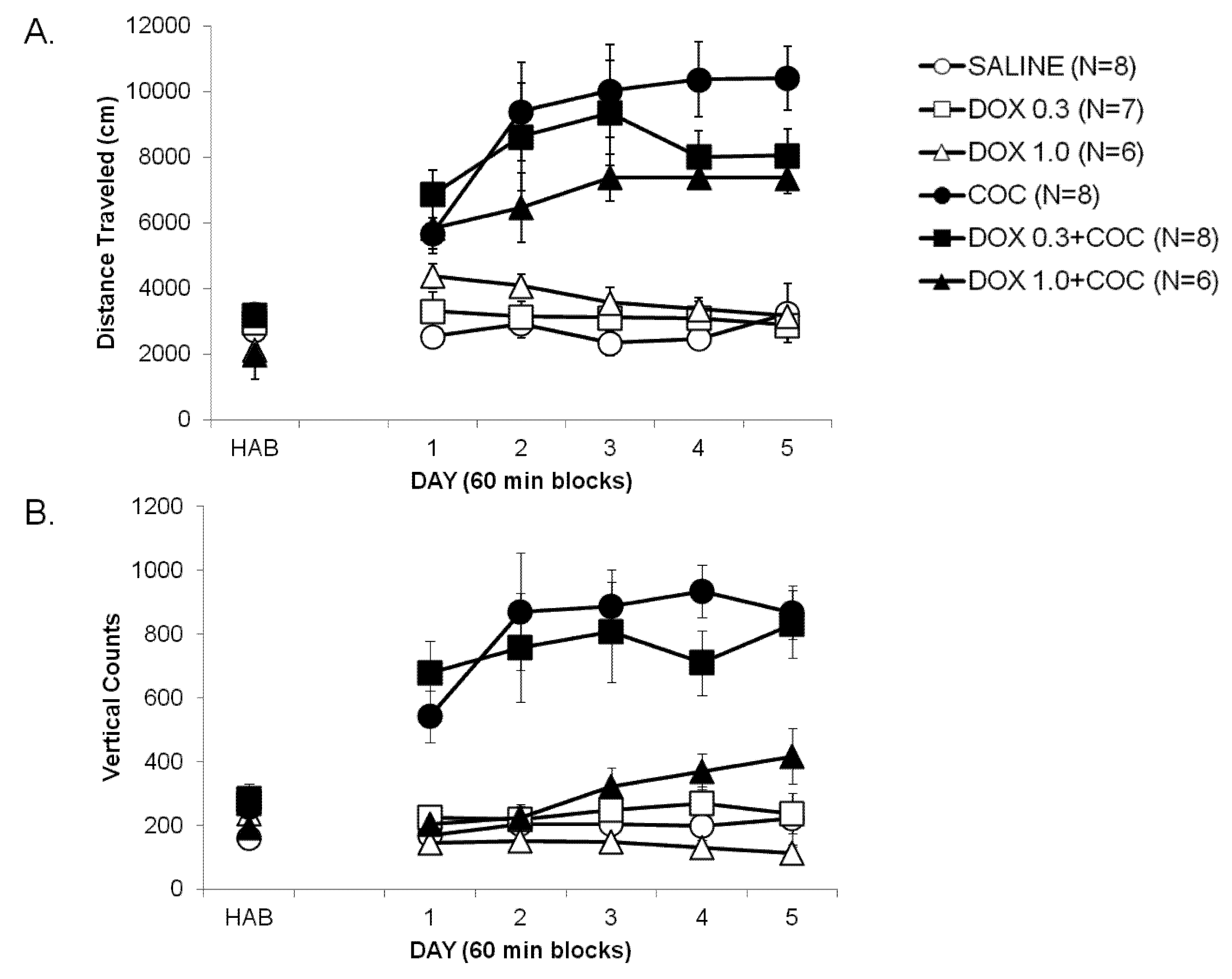

2.1. Development of Locomotor Sensitization to Cocaine (Development, Days 1–5)

2.2. Expression of Locomotor Sensitization to Cocaine (Day 15 Drug Challenge)

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Animals

3.2. Test Apparatus

3.3. Drugs

3.4. Groups

3.5. Locomotor Sensitization Procedure

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Fowler, J.S.; Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Gatley, S.J.; Logan, J. [(11)]Cocaine: PET studies of cocaine pharmacokinetics, dopamine transporter availability and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2001, 28, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, R.B.; Baumann, M.H.; Dersch, C.M.; Romero, D.V.; Rice, K.C.; Carroll, F.I.; Partilla, J.S. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse 2001, 39, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Chiara, G.; Imperato, A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 5274–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, H.O.; Ettenberg, A.; Bloom, F.E.; Koob, G.F. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology 1984, 84, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, M.C.; Lamb, R.J.; Goldberg, S.R.; Kuhar, M.J. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 1987, 237, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas, P.W.; Stewart, J. Dopamine transmission in the initiation and expression of drug- and stress-induced sensitization of motor activity. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1991, 16, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1993, 18, 247–291. [Google Scholar]

- Small, A.C.; Kampman, K.M.; Plebani, J.; De Jesus Quinn, M.; Peoples, L.; Lynch, K.G. Tolerance and sensitization to the effects of cocaine use in humans: A retrospective study of long-term cocaine users in Philadelphia. Subst. Use Misuse 2009, 44, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, C.N.; Mahoney, J.J., 3rd; Newton, T.F.; de La Garza, R., II. Pharmacotherapeutics directed at deficiencies associated with cocaine dependence: Focus on dopamine, norepinephrine and glutamate. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 134, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinshenker, D.; Schroeder, J.P. There and back again: A tale of norepinephrine and drug addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 1433–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfs, J.M.; Zhu, Y.; Druhan, J.P.; Aston-Jones, G.S. Origin of noradrenergic afferents to the shell subregion of the nucleus accumbens: Anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing studies in the rat. Brain Res. 1998, 806, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoto, P.; Flore, G.; Pani, L.; Gessa, G.L. Evidence for co-release of noradrenaline and dopamine from noradrenergic neurons in the cerebral cortex. Mol. Psychiatry 2001, 6, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moron, J.A.; Brockington, A.; Wise, R.A.; Rocha, B.A.; Hope, B.T. Dopamine uptake through the norepinephrine transporter in brain regions with low levels of the dopamine transporter: Evidence from knock-out mouse lines. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A.K.; Danysz, W.; Ogren, S.O.; Archer, T. Central noradrenaline depletion attenuates amphetamine-induced locomotor behavior. Neurosci. Lett. 1986, 64, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, S.; Grenhoff, J.; Chouvet, G.; Gonon, F.G.; Svensson, T.H. Prefrontal cortex regulates burst firing and transmitter release in rat mesolimbic dopamine neurons studied in vivo. Neurosci. Lett. 1993, 157, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, R.; Morrone, C.; Puglisi-Allegra, S. Prefrontal/accumbal catecholamine system determines motivational salience attribution to both reward- and aversion-related stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5181–5186. [Google Scholar]

- Gaval-Cruz, M.; Weinshenker, D. Mechanisms of disulfiram-induced cocaine abstinence: Antabuse and cocaine relapse. Mol. Interv. 2009, 9, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, P.P.; Trogu, E.; Vacca, R.; Amato, L.; Vecchi, S.; Davoli, M. Disulfiram for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, G.; Trovero, F.; Vezina, P.; Herve, D.; Godeheu, A.M.; Glowinski, J.; Tassin, J.P. Blockade of prefronto-cortical alpha 1-adrenergic receptors prevents locomotor hyperactivity induced by subcortical d-amphetamine injection. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994, 6, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darracq, L.; Blanc, G.; Glowinski, J.; Tassin, J.P. Importance of the noradrenaline-dopamine coupling in the locomotor activating effects of d-amphetamine. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 2729–2739. [Google Scholar]

- Drouin, C.; Darracq, L.; Trovero, F.; Blanc, G.; Glowinski, J.; Cotecchia, S.; Tassin, J.P. Alpha1b-adrenergic receptors control locomotor and rewarding effects of psychostimulants and opiates. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 2873–2884. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Rivera, C.A.; Feliu-Mojer, M.; Vazquez-Torres, R. Alpha-noradrenergic receptors modulate the development and expression of cocaine sensitization. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1074, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoddy, A.M.; Tessel, R.E. Prazosin: Effect on psychomotor-stimulant cues and locomotor activity in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985, 116, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, P.; Ho, D.; Cepeda-Benito, A.; Bellinger, L.; Nation, J. Cocaine-induced hypophagia and hyperlocomotion in rats are attenuated by prazosin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 455, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, S.; Mandyam, C.D.; Lekic, D.M.; Koob, G.F. Alpha 1-noradrenergic system role in increased motivation for cocaine intake in rats with prolonged access. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 18, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Kosten, T.A. Previous exposure to cocaine enhances cocaine self-administration in an alpha 1-adrenergic receptor dependent manner. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Kosten, T.A. Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, reduces cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 1202–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, H.L.; Meredith, P.A.; Sumner, D.J.; McLean, K.; Reid, J.L. A pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic assessment of a new alpha-adrenoceptor antagonist, doxazosin (UK33274) in normotensive subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1982, 13, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, T.F.; De La Garza, R., 2nd; Brown, G.; Kosten, T.R.; Mahoney, J.J., 3rd; Haile, C.N. Noradrenergic alpha(1) receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: A randomized trial. PloS One 2012, 7, e30854. [Google Scholar]

- Haile, C.N.; During, M.J.; Jatlow, P.I.; Kosten, T.R.; Kosten, T.A. Disulfiram facilitates the development and expression of locomotor sensitization to cocaine in rats. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, C.W., 3rd; Gonzales, R.A.; Moerschbaecher, J.M. Prazosin attenuates the effects of cocaine on motor activity but not on schedule-controlled behavior in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1992, 43, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selken, J.; Nichols, D.E. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors mediate the locomotor response to systemic administration of (+/−)-3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007, 86, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplaetse, T.L.; Rasmussen, D.D.; Froehlich, J.C.; Czachowski, C.L. Effects of prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, on the seeking and intake of alcohol and sucrose in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 36, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, L.; Lanteri, C.; Glowinski, J.; Tassin, J.P. Behavioral sensitization to amphetamine results from an uncoupling between noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7476–7481. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren, L.J.; Beemster, P.; Schoffelmeer, A.N. On the role of noradrenaline in psychostimulant-induced psychomotor activity and sensitization. Psychopharmacology 2003, 169, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, R.E.; Ryabinin, A.E.; Berger, S.P.; Lattal, K.M. Post-retrieval disruption of a cocaine conditioned place preference by systemic and intrabasolateral amygdala beta2- and alpha1-adrenergic antagonists. Learn. Mem. 2009, 16, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spealman, R.D. Noradrenergic involvement in the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ecke, L.E.; Elmer, G.I.; Suto, N. Cocaine self-administration is not dependent upon mesocortical alpha1 noradrenergic signaling. Neuroreport 2012, 23, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolverton, W.L. Evaluation of the role of norepinephrine in the reinforcing effects of psychomotor stimulants in rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1987, 26, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.H.; Seviour, P.W.; Iversen, S.D. Amphetamine and apomorphine responses in the rat following 6-OHDA lesions of the nucleus accumbens septi and corpus striatum. Brain Res. 1975, 94, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, E.; Goodrich, C.; Harlan, P.; Madras, B.K.; Graybiel, A.M. Repetitive behaviors in monkeys are linked to specific striatal activation patterns. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 7557–7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliane, V.; Perez, S.; Nieoullon, A.; Deniau, J.M.; Kemel, M.L. Cocaine-induced stereotypy is linked to an imbalance between the medial prefrontal and sensorimotor circuits of the basal ganglia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Brody, A.L.; Schwartz, J.M.; Baxter, L.R. Neuroimaging and frontal-subcortical circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl. 1998, 173, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rommelfanger, K.S.; Mitrano, D.A.; Smith, Y.; Weinshenker, D. Light and electron microscopic localization of alpha-1 adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat striatum and ventral midbrain. Neuroscience 2009, 158, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, N.; Bernardi, G.; Mercuri, N.B. Alpha(1)-adrenoceptor-mediated excitation of substantia nigra pars reticulata neurons. Neuroscience 2000, 98, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.J.; Pettinati, H.M.; Kampman, K.M.; O’Brien, C.P. The status of disulfiram: A half of a century later. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 26, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. A review of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of disulfiram and its metabolites. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 1992, 369, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, C.N.; De La Garza, R., 2nd; Mahoney, J.J.; Nielsen, D.A.; Kosten, T.R.; Newton, T.F. The impact of disulfiram treatment on the reinforcing effects of cocaine. PloS One 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveto, A.; Poling, J.; Mancino, M.J.; Feldman, Z.; Cubells, J.F.; Pruzinsky, R.; Gonsai, K.; Cargile, C.; Sofuoglu, M.; Chopra, M.P.; et al. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of disulfiram for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-stabilized patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 113, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, O.; Borg, S.; Holmstedt, B.; Kvande, H.; Shroder, R. Concentration of serotonin metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid from alcoholics before and during disulfiram therapy. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. (Copenh.) 1980, 47, 305–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, Y.H.; Liow, J.S.; Zoghbi, S.; Fujita, M.; Collins, J.; Tipre, D.; Sangare, J.; Hong, J.; Pike, V.W.; Innis, R.B. Disulfiram inhibits defluorination of (18)F-FCWAY, reduces bone radioactivity, and enhances visualization of radioligand binding to serotonin 5-HT1A receptors in human brain. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoto, P.; Flore, G.; Saba, P.; Cadeddu, R.; Gessa, G.L. Disulfiram stimulates dopamine release from noradrenergic terminals and potentiates cocaine-induced dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology 2012, 219, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, A.C.; Wolf, M.E. Behavioral sensitization to cocaine is associated with increased AMPA receptor surface expression in the nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 9144–9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.J.; Dietz, D.M.; Dumitriu, D.; Morrison, J.H.; Malenka, R.C.; Nestler, E.J. The addicted synapse: Mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 2010, 33, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.B.; O’Donnell, P.; Card, J.P.; Sesack, S.R. Dopamine terminals in the rat prefrontal cortex synapse on pyramidal cells that project to the nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 11049–11060. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemzadeh, M.B.; Mueller, C.; Vasudevan, P. Behavioral sensitization to cocaine is associated with increased glutamate receptor trafficking to the postsynaptic density after extended withdrawal period. Neuroscience 2009, 159, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesack, S.R.; Pickel, V.M. Prefrontal cortical efferents in the rat synapse on unlabeled neuronal targets of catecholamine terminals in the nucleus accumbens septi and on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992, 320, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.E.; Ferrario, C.R. AMPA receptor plasticity in the nucleus accumbens after repeated exposure to cocaine. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.E.; Moore, R.Y. Ascending projections of the locus coeruleus in the rat. II. Autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1977, 127, 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mejias-Aponte, C.A.; Drouin, C.; Aston-Jones, G. Adrenergic and noradrenergic innervation of the midbrain ventral tegmental area and retrorubral field: Prominent inputs from medullary homeostatic centers. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 3613–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrano, D.A.; Schroeder, J.P.; Smith, Y.; Cortright, J.J.; Bubula, N.; Vezina, P.; Weinshenker, D. Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors are localized on presynaptic elements in the nucleus accumbens and regulate mesolimbic dopamine transmission. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 2161–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigusa, T.; Aono, Y.; Uchida, T.; Takada, K.; Verheij, M.M.; Koshikawa, N.; Cools, A.R. The alpha(1)-, but not alpha(2)-, adrenoceptor in the nucleus accumbens plays an inhibitory role upon the accumbal noradrenaline and dopamine efflux of freely moving rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez-Martinez, M.C.; Vazquez-Torres, R.; Jimenez-Rivera, C.A. Activation of alpha1-adrenoceptors enhances glutamate release onto ventral tegmental area dopamine cells. Neuroscience 2012, 216, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Lin, S.K. Neurochemical interaction between dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex. Synapse 2004, 53, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommermeyer, H.; Frielingsdorf, J.; Knorr, A. Effects of prazosin on the dopaminergic neurotransmission in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 276, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, R.; Cabib, S.; Alcaro, A.; Orsini, C.; Puglisi-Allegra, S. Norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex is critical for amphetamine-induced reward and mesoaccumbens dopamine release. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 1879–1885. [Google Scholar]

- Villegier, A.S.; Drouin, C.; Bizot, J.C.; Marien, M.; Glowinski, J.; Colpaert, F.; Tassin, J.P. Stimulation of postsynaptic alpha1b- and alpha2-adrenergic receptors amplifies dopamine-mediated locomotor activity in both rats and mice. Synapse 2003, 50, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bunney, B.S.; Shi, W.X. Differential effects of cocaine on firing rate and pattern of dopamine neurons: Role of alpha1 receptors and comparison with l-dopa and apomorphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 317, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Auclair, A.; Drouin, C.; Cotecchia, S.; Glowinski, J.; Tassin, J.P. 5-HT2A and alpha1b-adrenergic receptors entirely mediate dopamine release, locomotor response and behavioural sensitization to opiates and psychostimulants. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 20, 3073–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalepa, I.; Witarski, T.; Kowalska, M.; Filip, M.; Vetulani, J. Effect of cocaine sensitization on alpha1-adrenoceptors in brain regions of the rat: An autoradiographic analysis. Pharmacol. Rep. 2006, 58, 827–835. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Y.; Matsubara, H.; Nose, A.; Shibasaki, Y.; Masaki, H.; Kosaki, A.; Okigaki, M.; Fujiyama, S.; Tanaka-Uchiyama, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; et al. Safety and availability of doxazosin in treating hypertensive patients with chronic renal failure. Hypertens. Res. 2001, 24, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykretowicz, A.; Guzik, P.; Wysocki, H. Doxazosin in the current treatment of hypertension. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2008, 9, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Haile, C.N.; Hao, Y.; O'Malley, P.W.; Newton, T.F.; Kosten, T.A. The α1 Antagonist Doxazosin Alters the Behavioral Effects of Cocaine in Rats. Brain Sci. 2012, 2, 619-633. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2040619

Haile CN, Hao Y, O'Malley PW, Newton TF, Kosten TA. The α1 Antagonist Doxazosin Alters the Behavioral Effects of Cocaine in Rats. Brain Sciences. 2012; 2(4):619-633. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2040619

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaile, Colin N., Yanli Hao, Patrick W. O'Malley, Thomas F. Newton, and Therese A. Kosten. 2012. "The α1 Antagonist Doxazosin Alters the Behavioral Effects of Cocaine in Rats" Brain Sciences 2, no. 4: 619-633. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2040619