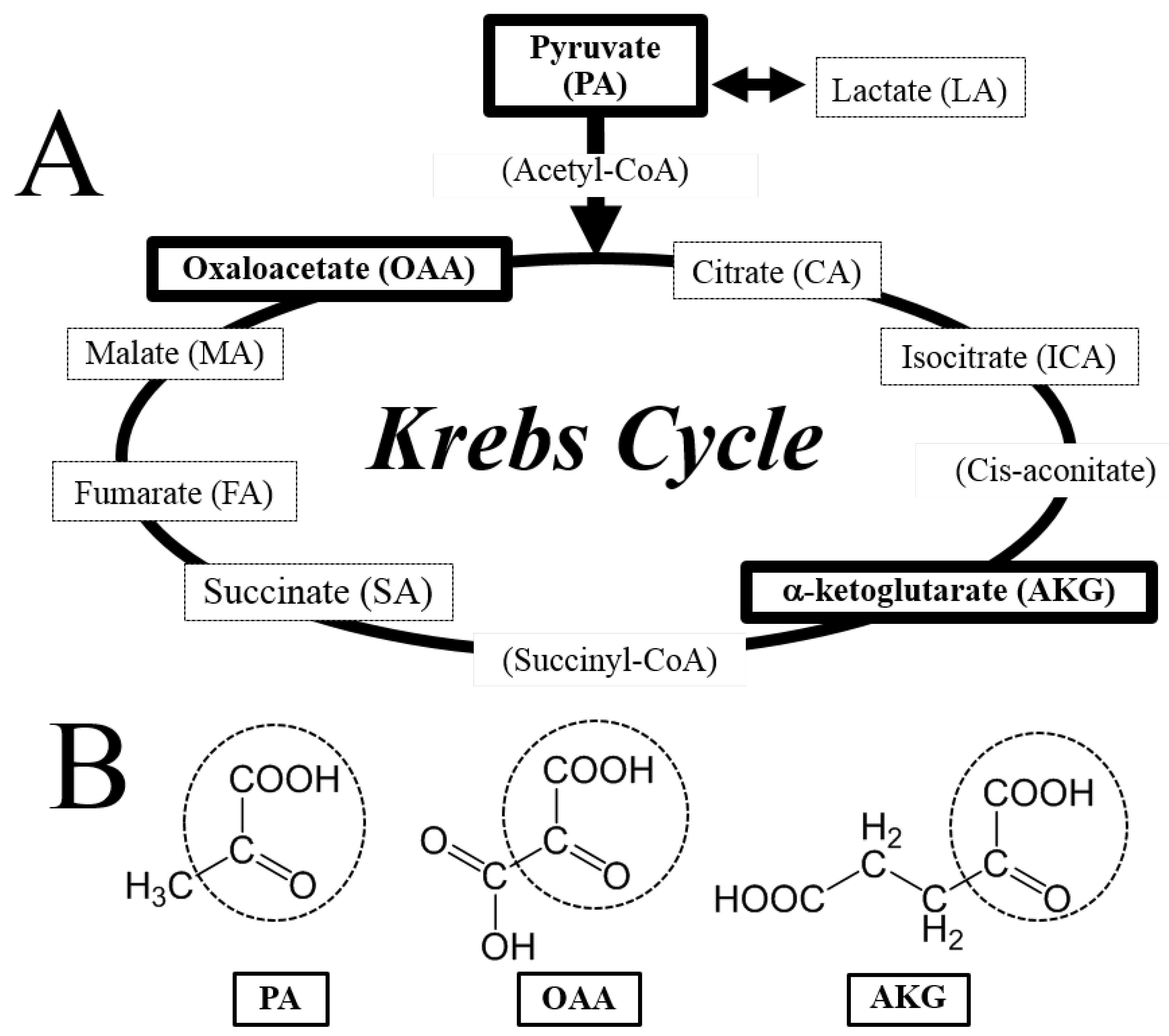

Krebs Cycle Intermediates Protective against Oxidative Stress by Modulating the Level of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neuronal HT22 Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. HT22 Cultures and MTT Assay

2.3. DCF Assay

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

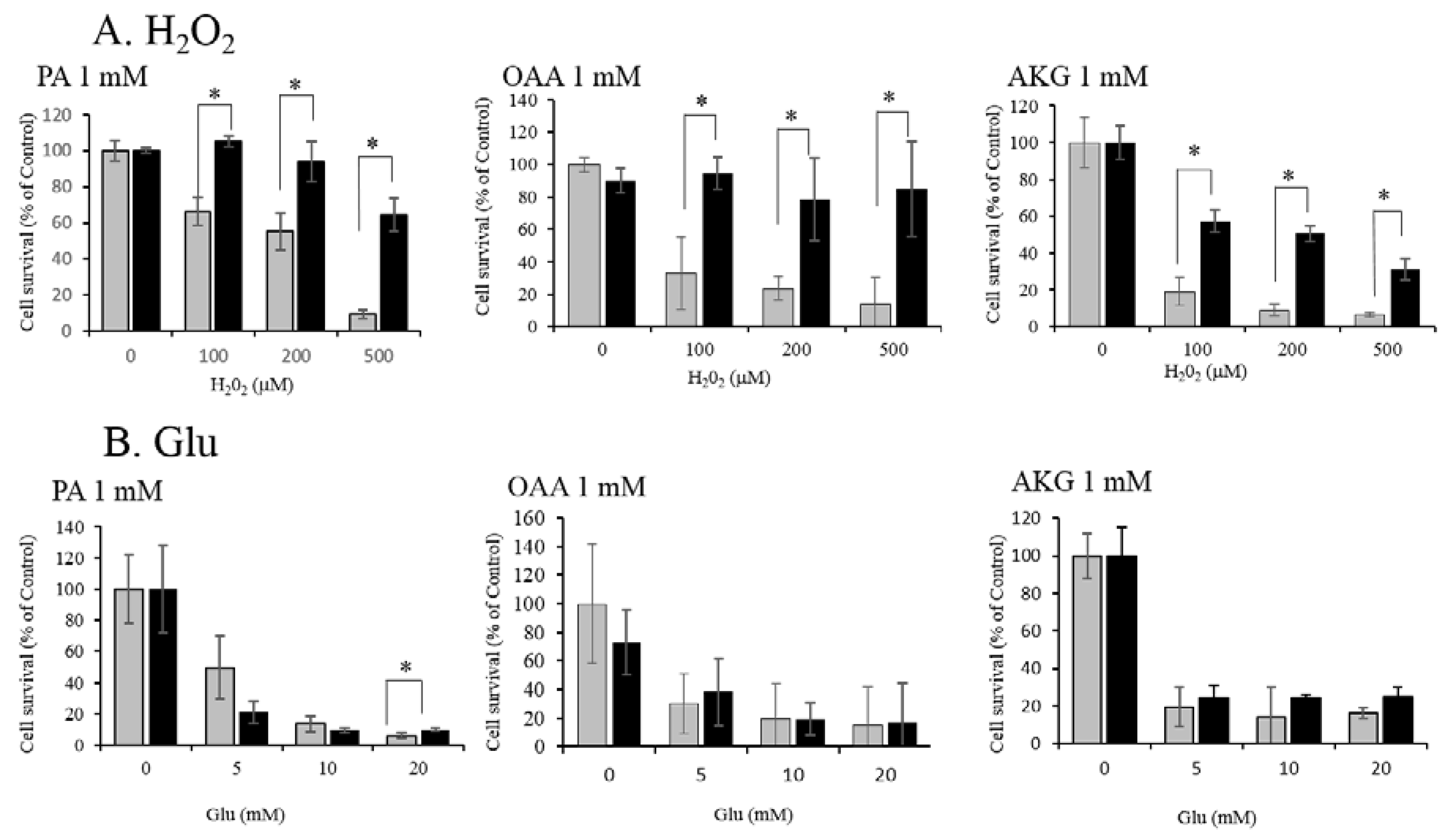

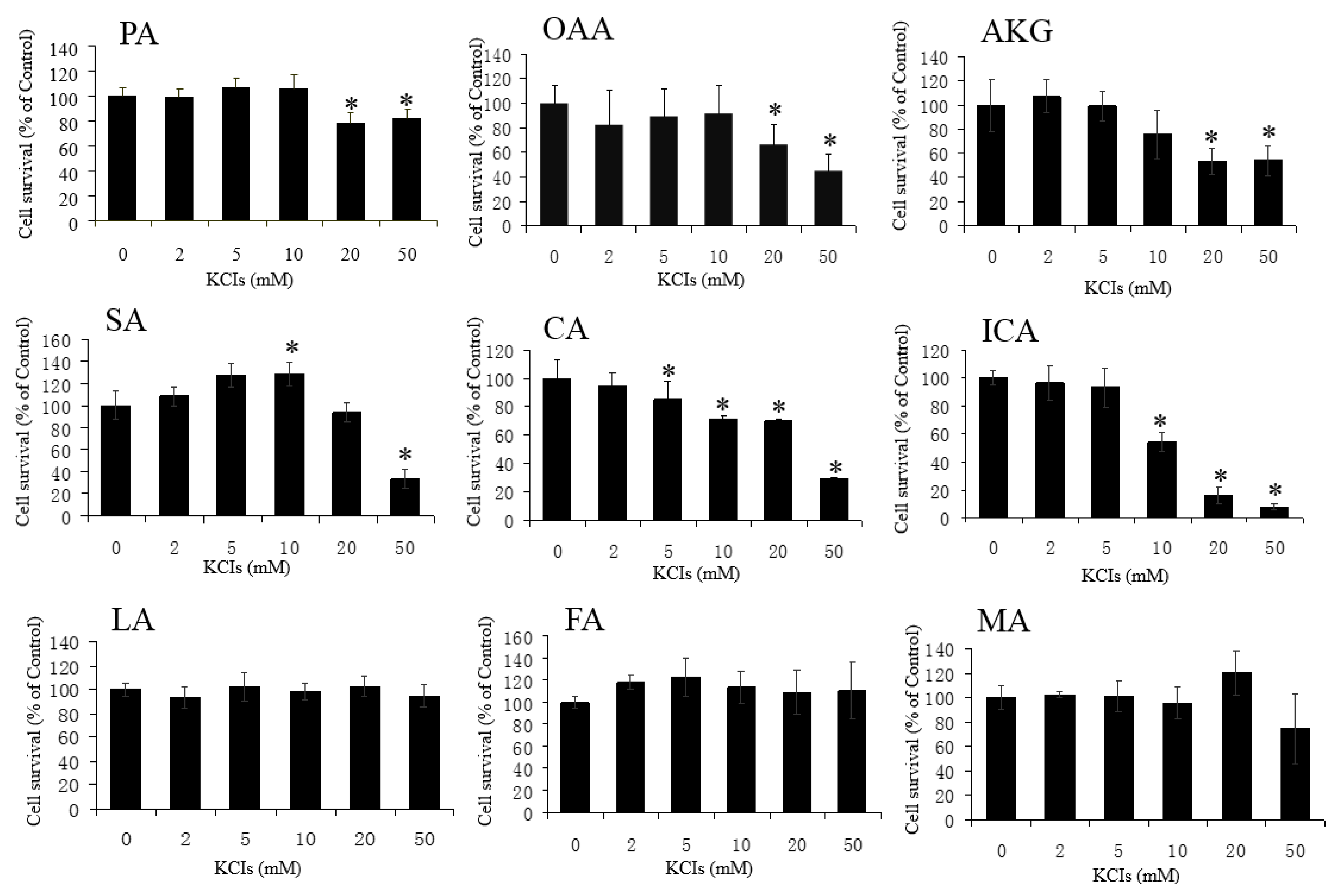

3.1. Neuroprotective Effect of PA, OAA, and AKG on HT22 Cells

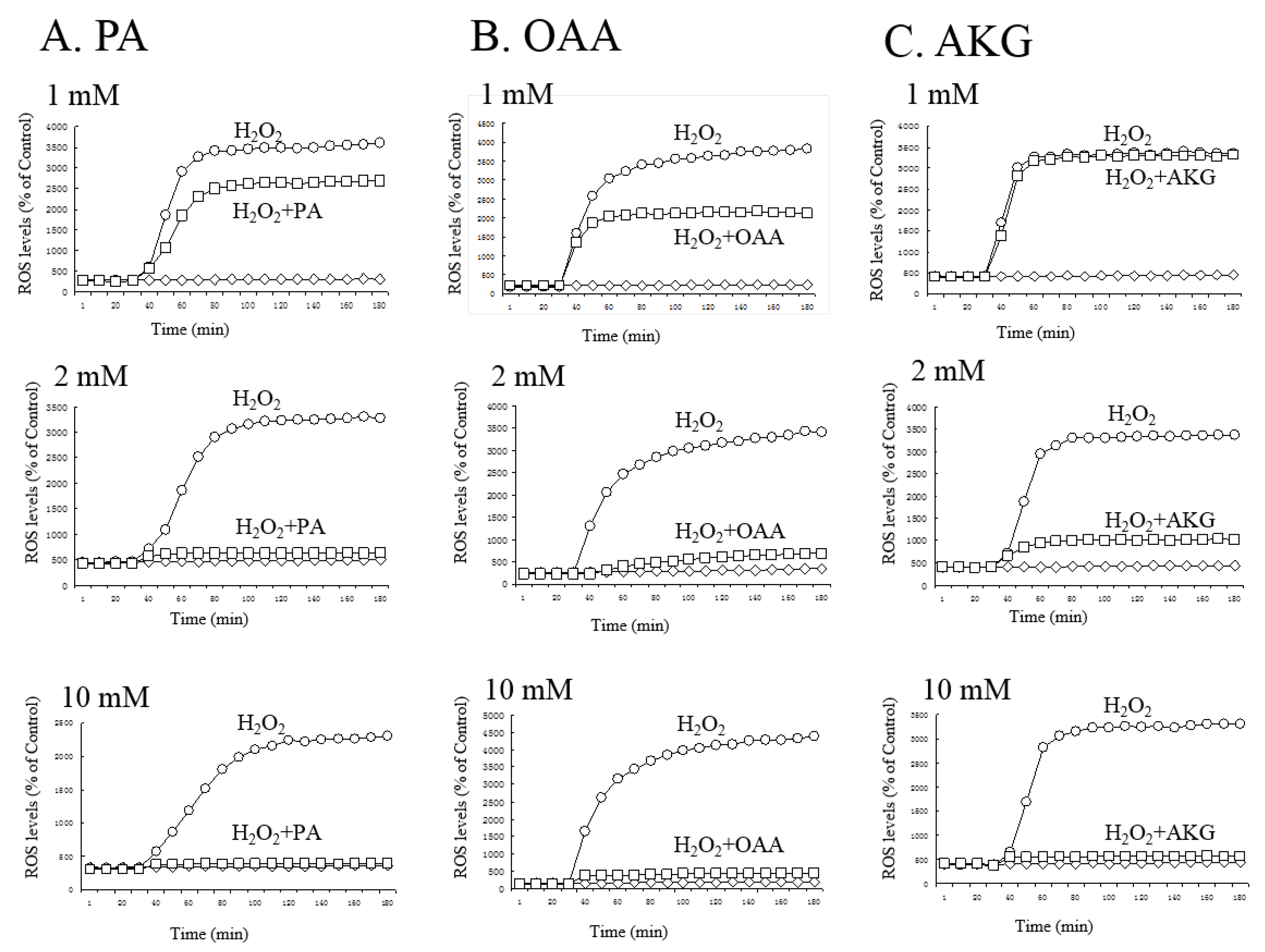

3.2. Regulation of ROS by PA, OAA, and AKG

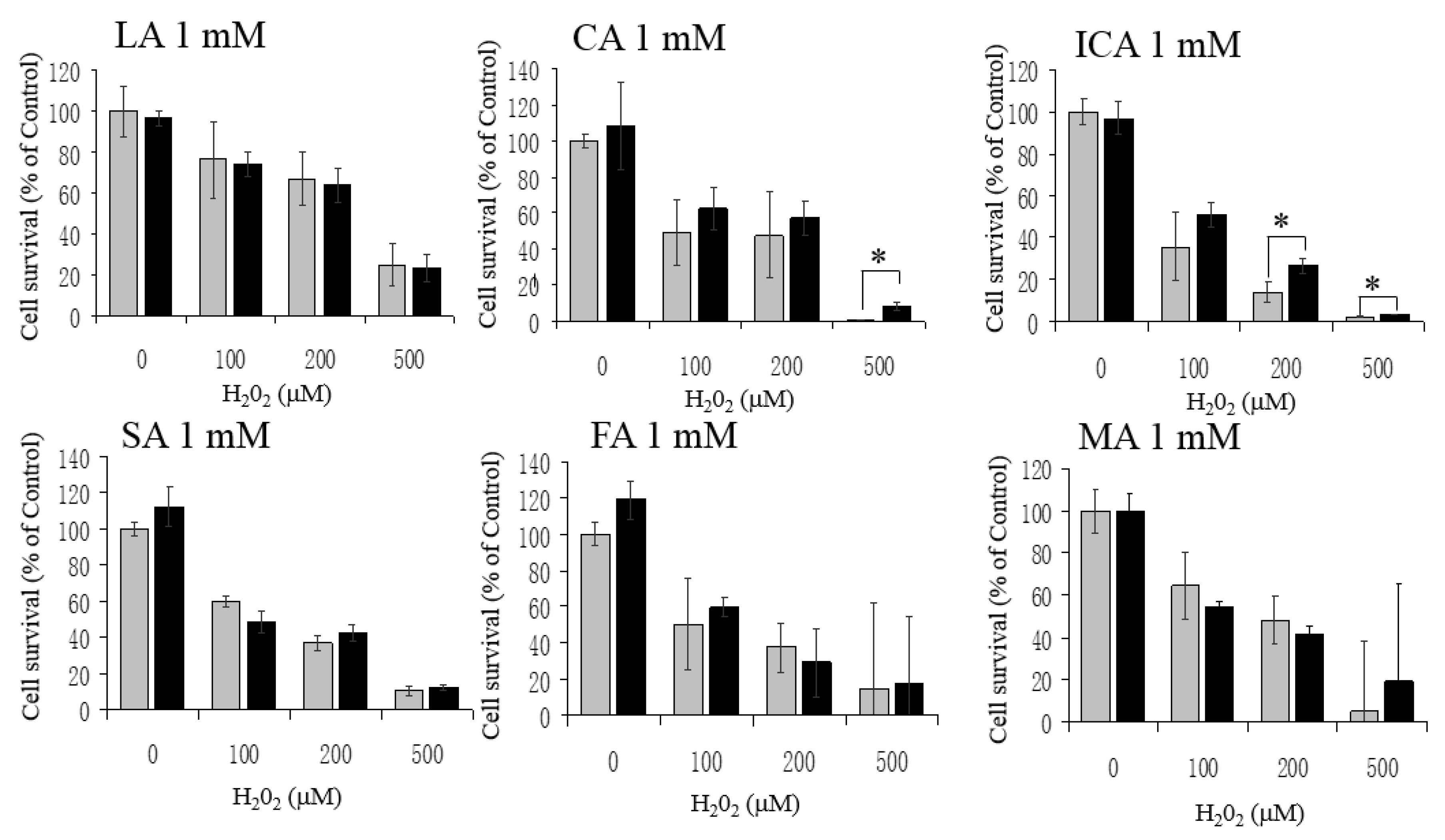

3.3. No Protective Effects by LA, CA, ICA, SA, FA, and MA against H2O2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Abbreviations

References

- Krebs, H.A. The citric acid cycle and the Szent-Györgyi cycle in pigeon breast muscle. Biochem. J. 1940, 34, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locasale, J.W.; Cantley, L.C. Metabolic flux and the regulation of mammalian cell growth. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Berardinis, R.J.; Thompson, C.B. Cellular metabolism and disease: What do metabolic outliers teach us? Cell 2012, 148, 1132–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.B.; Copes, N.; Brito, A.G.; Canfield, J.; Bradshaw, P.C. Malate and fumarate extend lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.S.; Cash, A.; Hamadani, L.; Diemer, T. Oxaloacetate supplementation increases lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans through an AMPK/FOXO-dependent pathway. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishur, R.J.; Khan, M.; Munkácsy, E.; Sharma, L.; Bokov, A.; Beam, H.; Radetskaya, O.; Borror, M.; Lane, R.; Bai, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial metabolites extend lifespan. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czibik, G.; Steeples, V.; Yavari, A.; Ashrafian, H. Citric acid cycle intermediates in cardioprotection. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2014, 7, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desagher, S.; Glowinski, J.; Prémont, J. Pyruvate protects neurons against hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 9060–9067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrae, U.; Singh, J.; Ziegler, S.K. Pyruvate and related alpha keto acids protect mammalian cells in culture against hydrogen peroxide induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 1985, 28, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; van Hoecke, M.; Tang, X.N.; Lee, H.; Zheng, Z.; Swanson, R.A.; Yenari, M.A. Pyruvate protects against experimental stroke via an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 36, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isopi, E.; Granzotto, A.; Corona, C.; Bomba, M.; Ciavardelli, D.; Curcio, M.; Canzoniero, L.M.; Navarra, R.; Lattanzio, R.; Piantelli, M.; et al. Pyruvate prevents the development of age-dependent cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease without reducing amyloid and tau pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 81, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reczek, C.R.; Chandel, N.S. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now? J. Neurochem. 2006, 97, 1634–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaki, Y.; Tabuchi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Kosaka, K.; Satoh, T. Activated glutathione metabolism participates in protective effects of carnosic acid against oxidative stress in neuronal HT22 cells. Planta Med. 2009, 76, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Rezaie, T.; Seki, M.; Sunico, C.R.; Tabuchi, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Yanagitai, M.; Senzaki, M.; Kosegawa, C.; Taira, H.; et al. Dual neuroprotective pathways of a pro-electrophilic compound via HSF-1-activated heat-shock proteins and Nrf2-activated phase 2 antioxidant response enzymes. J. Neurochem. 2011, 19, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Stalder, R.; McKercher, S.R.; Williamson, R.E.; Roth, G.P.; Lipton, S.A. Nrf2 and HSF-1 pathway activation via hydroquinone-based proelectrophilic small molecules is regulated by electrochemical oxidation potential. ASN Neuro 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Perez, E.; Liu, R.Y.; Yan, L.J.; Mallet, R.T.; Yang, S.H. Pyruvate protects mitochondria from oxidative stress in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Brain Res. 2007, 1132, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafian, H.; Czibik, G.; Bellahcene, M.; Aksentijević, D.; Smith, A.C.; Mitchell, S.J.; Dodd, M.S.; Kirwan, J.; Byrne, J.J.; Ludwig, C.; et al. Fumarate is cardioprotective via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Kosaka, K.; Itoh, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Shimojo, Y.; Kitajima, C.; Cui, J.; Kamins, J.; Okamoto, S.; et al. Carnosic acid, a catechol-type electrophilic compound, protects neurons both in vitro and in vivo through activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway via S-alkylation of targeted cysteines on Keap1. J. Neurochem. 2008, 104, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Izumi, M.; Inukai, Y.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Nakayama, N.; Kosaka, K.; Shimojo, Y.; Kitajima, C.; Itoh, K.; Yokoi, T.; et al. Carnosic acid protects neuronal HT22 cells through activation of the antioxidant-responsive element in free carboxylic acid- and catechol hyroxyl moieties-dependent manners. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 434, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, H.; Koyama, T.; Yamada, S.; Lipton, S.A.; Satoh, T. Zonarol, a sesquiterpene from the brown algae Dictyopteris undulata, provides neuroprotection by activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 457, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Koyama, T.; Noguchi, H.; Ueda, Y.; Kitsuyama, R.; Shimizu, H.; Tanimoto, A.; Wang, K.Y.; Nawata, A.; Nakayama, T.; et al. Marine hydroquinone zonarol prevents inflammation and apoptosis in dextran sulfate sodium-induced mice ulcerative colitis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Saitoh, S.; Hosaka, M.; Kosaka, K. Simple ortho- and para-hydroquinones as compounds neuroprotective against oxidative stress in a manner associated with specific transcriptional activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 379, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; McKercher, S.R.; Lipton, S.A. The Nrf2-targetted antioxidant actions of pro-electrophilic drugs. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, S.A.; Rezaie, T.; Nutter, A.; Lopez, K.M.; Parker, J.; Kosaka, K.; Satoh, T.; McKercher, S.R.; Masliah, E.; Nakanishi, N. Therapeutic advantage of pro-electrophilic drugs to activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway in Alzheimer’s disease models. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Lipton, S.A. Redox regulation of neuronal survival mediated by electrophilic compounds. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sawa, K.; Uematsu, T.; Korenaga, Y.; Hirasawa, R.; Kikuchi, M.; Murata, K.; Zhang, J.; Gai, X.; Sakamoto, K.; Koyama, T.; et al. Krebs Cycle Intermediates Protective against Oxidative Stress by Modulating the Level of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neuronal HT22 Cells. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6010021

Sawa K, Uematsu T, Korenaga Y, Hirasawa R, Kikuchi M, Murata K, Zhang J, Gai X, Sakamoto K, Koyama T, et al. Krebs Cycle Intermediates Protective against Oxidative Stress by Modulating the Level of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neuronal HT22 Cells. Antioxidants. 2017; 6(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleSawa, Kenta, Takumi Uematsu, Yusuke Korenaga, Ryuya Hirasawa, Masatoshi Kikuchi, Kyohei Murata, Jian Zhang, Xiaoqing Gai, Kazuichi Sakamoto, Tomoyuki Koyama, and et al. 2017. "Krebs Cycle Intermediates Protective against Oxidative Stress by Modulating the Level of Reactive Oxygen Species in Neuronal HT22 Cells" Antioxidants 6, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox6010021