The Appropriateness of Footwear in Diabetic Patients Observed during a Podiatric Examination: A Prospective Observational Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Identification of the at-risk foot.

- Regular inspection and examination of the at-risk foot.

- Patient, family and healthcare provider education.

- Routine use of appropriate footwear.

- Regular monitoring of risk factors for ulceration.

- Diabetic patients should always use accommodative, properly fitted therapeutic footwear (TF).

- In presence of LOPS, the feet should be protected with the suggestion of not walking barefoot, not wearing footwear without socks and never using thin-soled slippers, both indoors and outdoors.

- Patients with LOPS should have access to TF and should be encouraged to wear it all the day.

- Patients with foot deformities should always wear TF accommodating their foot shape with appropriate fitting.

- (a)

- Is there enough patient knowledge on the basic principles of preventive footwear according to their foot ulcerative risk level?

- (b)

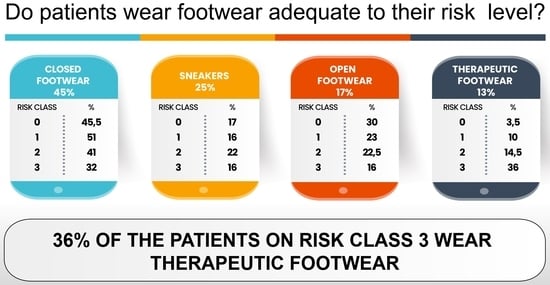

- Do patients wear footwear adequate to their ulcerative risk level?

2. Materials and Methods

- Demographic data.

- Definition of ulceration risk.

- Types and characteristics of footwear (Supplementary S2 and S3).

- Patient’s questionnaire.

2.1. Demographic Data

2.2. Definition of Ulceration Risk

- −

- Class 0 includes patients at very low risk of ulceration, without LOPS and without PAD.

- −

- Class 1 includes patients at low risk of ulceration, with LOPS or PAD but without foot deformities.

- −

- Class 2 includes patients at moderate risk of ulceration, with LOPS and PAD, or LOPS and foot deformity or PAD and deformity.

- −

- Class 3 includes patients with LOPS or PAD and one or more of the following: histories of a foot ulcer, minor or major amputation.

2.3. Types and Characteristics of Footwear

- −

- Type a—Open: off-the-shelf sandals and similar (flip-flops, sandals, open slippers).

- −

- Type b—Closed: off-the-shelf standard closed shoes (moccasins, décolleté, slippers, boots).

- −

- Type c—Sneakers: off-the-shelf sporty and gymnastic footwear.

- −

- Type d—Therapeutic footwear: off-the-shelf or custom-made, designed to accommodate customized foot orthosis, without internal seams, with rigid or semi-rigid out-sole and flexible, elastic or self-modeling upper, extra depth and rocker bottom out-sole.

- −

- For IWGDF risk 1–3 with no or limited foot deformity, no pre-ulcerative lesions and no plantar ulcer history, shoes that accommodates the shape of the feet and that fit properly.

- −

- For IWGDF risk 2 or 3 with a foot deformity that significantly increases pressure or a pre-ulcerative lesion, extra-depth shoes, custom-made footwear, custom-made insoles and/or toe orthoses.

- −

- For IWGDF risk 3 with a healed plantar foot ulcer, therapeutic shoes that have a demonstrated plantar pressure relieving effect during walking, to help prevent a re-current plantar foot ulcer.

2.4. Patient’s Questionnaire

- −

- Four questions related to education on footwear.

- −

- Four questions related to patient awareness about the role of footwear.

- −

- Two questions on adherence.

| 1 | The footwear you are wearing today was recommended by someone? □ YES □ NO From who? □ Endocrinologist □ Podiatrist □ Physiatrist □ Orthopedic technician □ Orthopedic □ Other: _____________________ |

| 2 | Do you think you are wearing suitable footwear? □ YES □ NO |

| 3 | How many hours a day do you wear this footwear? ________________ |

| 4 | Do you think foot ulcers can come from footwear? □ YES □ NO |

| 5 | Have you ever been told your feet are at risk of (re)ulceration? □ YES □ NO |

| 6 | Do you think they are? □ YES □ NO |

| 7 | Have you ever received any recommendation on choosing footwear? □ YES □ NO |

| 8 | Do you remember at least three? 1______________________ 2 _______________________ 3 ______________________ |

| 9 | Can you follow these recommendations? □ YES □ NO |

| 10 | Do you think they are excessive? □ YES □ NO |

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Ulceration Risk Class

3.3. Patient Questionnaire

- Only 28% of patients wore footwear recommended by someone, principally by endocrinologists (13%) and podiatrists (9%)

- A total of 90% of the patients thought they wore appropriate footwear.

- Patients wore the footwear for an average of 8 ± 3.9 h a day.

- A total of 57% of patients thought that foot ulcers might come from footwear.

- A total of 51% of the patients were informed about foot (re)ulceration risk.

- A total of 37% thought that their feet were at risk of (re)ulceration.

- A total of 45% of patients had knowledge of the footwear they needed to wear.

- Mostly, the recommendations were to wear TF, with a flexible upper, without internal seams, predisposed to insole, etc.

- A total of 43% could follow the recommendations.

- A total of 91% of patients thought that the recommendations were not excessive.

3.4. Types and Characteristics of the Footwear

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maciejewski, M.L.; Reiber, G.E.; Smith, D.G.; Wallace, C.; Hayes, S.; Boyko, E.J. Effectiveness of Diabetic Therapeutic Footwear in Preventing Reulceration. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaper, N.C.; van Netten, J.J.; Apelqvist, J.; Bus, S.A.; Fitridge, R.; Game, F.; Monteiro-Soares, M.; Senneville, E.; IWGDF Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the prevention and management of diabetes-related foot disease (IWGDF 2023 update). Diabetes Metab. Res Rev. 2024, 40, e3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srass, H.; Ead, J.K.; Armstrong, D.G. Adherence and the Diabetic Foot: High Tech Meets High Touch? Sensors 2023, 23, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, L.; Tedeschi, A.; Fallani, E.; Coppelli, A.; Vallini, V.; Iacopi, E.; Piaggesi, A. Custom-made orthesis and shoes in a structured follow-up program reduces the incidence of neuropathic ulcers in high-risk diabetic foot patients. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2012, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarl, G.; Hulshof, C.M.; Busch-Westbroek, T.E.; Bus, S.A.; van Netten, J.J. Adherence and Wearing Time of Prescribed Footwear among People at Risk of Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcers: Which Measure to Use? Sensors 2023, 23, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, E.A.; Boulton, A.J. Do people with diabetes wear their prescribed footwear? Diabet Med. 1996, 13, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waaijman, R.; Keukenkamp, R.; de Haart, M.; Polomski, W.P.; Nollet, F.; Bus, S.A. Adherence to wearing prescription custom-made footwear in patients with diabetes at high risk for plantar foot ulceration. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1613–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingorani, A.; LaMuraglia, G.M.; Henke, P.; Meissner, M.H.; Loretz, L.; Zinszer, K.M.; Driver, V.R.; Frykberg, R.; Carman, T.L.; Marston, W.; et al. The management of diabetic foot: A clinical practice guideline by the Society for Vascular Surgery in collaboration with the American Podiatric Medical Association and the Society for Vascular Medicine. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 63 (Suppl. S2), 3S–21S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apelqvist, J.; Larsson, J.; Agardh, C. Long-term prognosis for diabetic patients with foot ulcers. J. Intern. Med. 1993, 233, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiber, G.E.; Smith, D.G.; Wallace, C.; Sullivan, K.; Hayes, S.; Vath, C.; Maciejewski, M.L.; Yu, O.; Heagerty, P.J.; LeMaster, J. Effect of therapeutic footwear on foot reulceration in patients with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002, 287, 2552–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Lavery, L.A.; Kimbriel, H.R.; Nixon, B.P.; Boulton, A.J. Activity patterns of patients with diabetic foot ulceration: Patients with active ulceration may not adhere to a standard pressure off-loading regimen. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26, 2595–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, C.; Stevenson, R.; Dolan, A. Evaluation of a diabetic foot screening and protection programme. Diabet. Med. 1998, 15, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, B.G.; Umadevi, V.; Shivaram, J.M.; Belehalli, P.; Shekar, M.A.; Chaluvanarayana, H.C.; Sikkandar, M.Y.; Brioschi, M.L. Diabetic Foot Assessment and Care: Barriers and Facilitators in a Cross-Sectional Study in Bangalore, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Weg, B. Compliance with orthopaedic footwear in patients with diabetes. Diabet. Foot J. 2002, 5, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- López-Moral, M.; Molines-Barroso, R.J.; Herrera-Casamayor, M.; García-Madrid, M.; García-Morales, E.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L. Usability of Different Methods to Assess and Improve Adherence to Therapeutic Footwear in Persons with the Diabetic Foot in Remission. A Systematic Review. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2023, 15347346231190680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bus, S.A.; Armstrong, D.G.; van Deursen, R.W.; Lewis, J.E.A.; Caravaggi, C.F.; Cavanagh, P.R. IWGDF guidance on footwear and offloading interventions to prevent and heal foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2016, 32 (Suppl. S1), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, S.A.; Waaijman, R.; Arts, M.; De Haart, M.; Busch-Westbroek, T.; Van Baal, J.; Nollet, F. Effect of custom-made footwear on foot ulcer recurrence in diabetes: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 4109–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, E.J.; Armstrong, D.G.; Lavery, L.A. Risk factors for recurrent diabetic foot ulcers: Site matters. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2077–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, N.; Chipchase, S.; Treece, K.; Game, F.; Jeffcoate, W. Ulcer-free survival following management of foot ulcers in diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2005, 22, 1306–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moral, M.; Molines-Barroso, R.J.; Altonaga-Calvo, B.J.; Carrascosa-Romero, E.; Cecilia-Matilla, A.; Dòria-Cervós, M.; García-Martínez, M.T.; Ortiz-Nistal, A.; Palma-Bravo, A.; Pereira-Losada, N.; et al. Evaluation of usability, adherence, and clinical efficacy of therapeutic footwear in persons with diabetes at moderate to high risk of diabetic foot ulcers: A multicenter prospective study. Clin. Rehabil. 2024, 38, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinchliffe, R.J.; Brownrigg, J.R.W.; Apelqvist, J.; Boyko, E.J.; Fitridge, R.; Mills, J.L.; Reekers, J.; Shearman, C.P.; Zierler, R.E.; Schaper, N.C.; et al. IWGDF guidance on the diagnosis, prognosis and management of peripheral artery disease in patients with foot ulcers in diabetes. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhatieb, M.T.; Alkhalifah, H.A.; Alkhalifah, Z.A.; Aljehani, K.M.; Almalki, M.S.; Alqarni, A.A.; Alqurashi, S.Z.; Alzahrani, R.A. The effect of therapeutic footwear on the recurrence and new formation of foot ulcers in previously affected diabetic patients in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemler, S.L.; Ntella, S.L.; Jeanmonod, K.; Köchli, C.; Tiwari, B.; Civet, Y.; Perriard, Y.; Pataky, Z. Intelligent plantar pressure offloading for the prevention of diabetic foot ulcers and amputations. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1166513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apelqvist, J.; Bakker, K.; van Houtum, W.H.; Schaper, N.C. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2008, 24 (Suppl. S1), S181–S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Netten, J.J.; Lazzarini, P.A.; Armstrong, D.G.; Bus, S.A.; Fitridge, R.; Harding, K.; Kinnear, E.; Malone, M.; Menz, H.B.; Perrin, B.M.; et al. Diabetic Foot Australia guideline on footwear for people with diabetes. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarl, G.; Lundqvist, L.-O. Adherence to wearing therapeutic shoes among people with diabetes: A systematic review and reflections. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Moral, M.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L.; García-Morales, E.; García-Álvarez, Y.; Álvaro-Afonso, F.J.; Molines-Barroso, R.J. Clinical efficacy of therapeutic footwear with a rigid rocker sole in the prevention of recurrence in patients with diabetes mellitus and diabetic polineuropathy: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ulbrecht, J.S.; Hurley, T.; Mauger, D.T.; Cavanagh, P.R. Prevention of recurrent foot ulcers with plantar pressure–based in-shoe orthoses: The careful prevention multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantelau, E.; Haage, P. An audit of cushioned diabetic footwear: Relation to patient compliance. Diabet. Med. 1994, 11, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janisse, D.; Janisse, E. Pedorthic management of the diabetic foot. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2015, 39, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.J.; Cochrane, L. Do patients with diabetes wear shoes of the correct size? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 1900–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, P.A.; Jarl, G.; Gooday, C.; Viswanathan, V.; Caravaggi, C.F.; Armstrong, D.G.; Bus, S.A. Effectiveness of offloading interventions to heal foot ulcers in persons with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2020, 36, e3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccioli, L.; Faglia, E.; Monticone, G.; Favales, F.; Durola, L.; Aldeghi, A.; Quarantiello, A.; Calia, P.; Menzinger, G. Manufactured shoes in the prevention of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 1995, 18, 1376–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, L.A.; LaFontaine, J.; Higgins, K.R.; Lanctot, D.R.; Constantinides, G. Shear-reducing insoles to prevent foot ulceration in high-risk diabetic patients. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2012, 25, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bădescu, S.; Tătaru, C.; Kobylinska, L.; Georgescu, E.; Zahiu, D.; Zăgrean, A.; Zăgrean, L. The association between Diabetes mellitus and Depression. J. Med. Life 2016, 9, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Price, P. How can we improve adherence? Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keukenkamp, R.; Merkx, M.J.; Busch-Westbroek, T.E.; Bus, S.A. An Explorative Study on the Efficacy and Feasibility of the Use of Motivational Interviewing to Improve Footwear Adherence in Persons with Diabetes at High Risk for Foot Ulceration. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2018, 108, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongebloed-Westra, M.; Bode, C.; van Netten, J.J.; Ten Klooster, P.M.; Exterkate, S.H.; Koffijberg, H.; van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C. Using motivational interviewing combined with digital shoe-fitting to improve adherence to wearing orthopaedic shoes in people with diabetes at risk of foot ulceration: Study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (average ± SD) | 71 ± 11.5 |

| DM duration (years ± SD) | 17 ± 11 |

| Sex (% male) | 56 |

| Insulin-treated (% yes) | 48 |

| Education level (% low) | 52 |

| Charcot (% yes) | 2 |

| Previous ulcer/amputation (% yes) | 24 |

| Active ulceration (% yes) | 15 |

| Deformity (% yes) | 58 |

| Risk Class | Closed | Open | Sneakers | Therapeutic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 45.5% | 17% | 30% | 3.5% |

| 1 | 51% | 16% | 23% | 10% |

| 2 | 41% | 22% | 22.5% | 14.5% |

| 3 | 32% | 16% | 16% | 36% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hazbiu, A.; Teobaldi, I.; Sepe, M.; Federici, G.; Meloni, M.; Uccioli, L. The Appropriateness of Footwear in Diabetic Patients Observed during a Podiatric Examination: A Prospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13082402

Hazbiu A, Teobaldi I, Sepe M, Federici G, Meloni M, Uccioli L. The Appropriateness of Footwear in Diabetic Patients Observed during a Podiatric Examination: A Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(8):2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13082402

Chicago/Turabian StyleHazbiu, Anisa, Ilaria Teobaldi, Mario Sepe, Giovanni Federici, Marco Meloni, and Luigi Uccioli. 2024. "The Appropriateness of Footwear in Diabetic Patients Observed during a Podiatric Examination: A Prospective Observational Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 8: 2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13082402