Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease: Three Distinct Clinical Entities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. ME

1.2. CFS

1.3. SEID

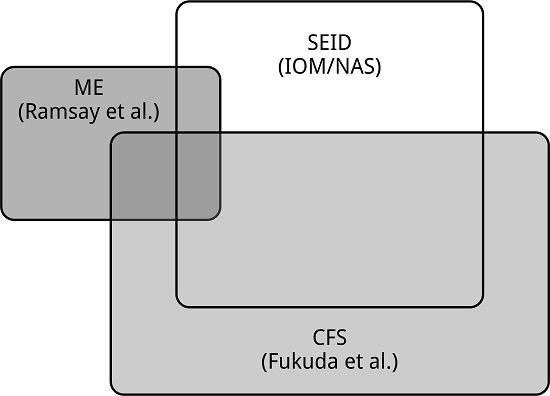

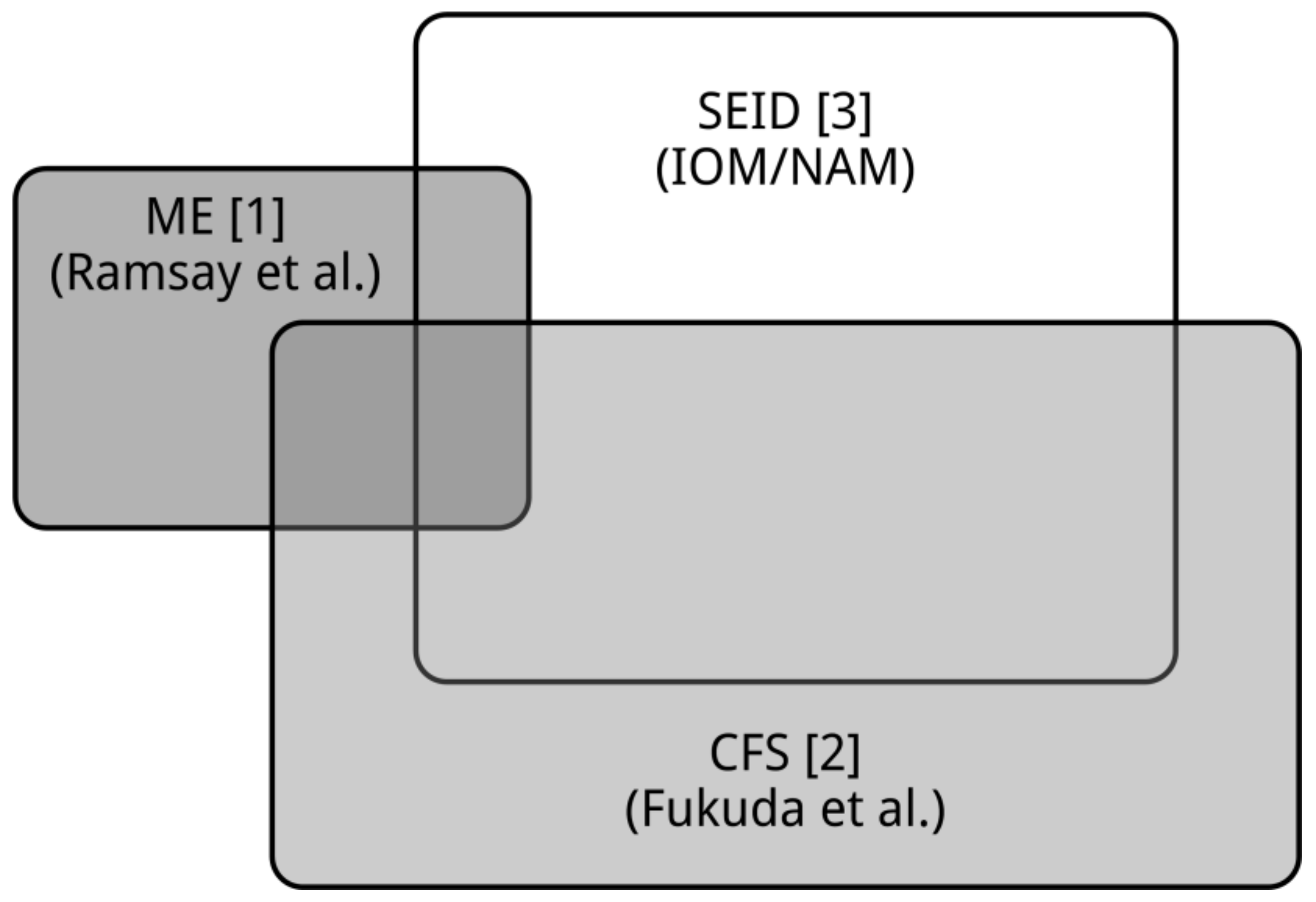

1.4. ME, CFS, and SEID: Three Distinct Entities

1.5. Diagnosis

2. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dowsett, E.G.; Ramsay, A.M.; McCartney, R.A.; Bell, E.J. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis—A persistent enteroviral infection? Postgrad. Med. J. 1990, 66, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, K.; Straus, S.E.; Hickie, I.; Sharpe, M.; Dobbins, J.G.; Komaroff, A.L. The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (National Academies of Medicine). Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness (Prepublication Draft); Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-309-31689-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam, A.G. Epidemiological Study on an Epidemic, Diagnosed as Poliomyelitis, Occurring among the Personnel of Los Angeles County General Hospital during the Summer of 1934; United States Treasury Department Public Health Service Public Health Bulletin: Washington, DC, USA, 1938; Volume 240, pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, N.; Nelson, M.; Stovin, S. Epidemiological aspects of an outbreak of encephalomyelitis at the Royal Free Hospital, London, in the summer of 1955. J. Hyg. 1957, 55, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdsson, B.; Sigurjonsson, J.; Sigurdsson, J.; Thorkelsson, J.; Gudmundsson, K. A disease epidemic in Iceland simulating poliomyelitis. Am. J. Hyg. 1950, 52, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellew, R.A.A. A clinical description of a disease resembling poliomyelitis, seen in Adelaide, 1949–1951. Med. J. Aust. 1951, 1, 944–946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acheson, D.E. A new clinical entity? Lancet 1956, 267, 789–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Acheson, D.E. The clinical syndrome variously called benign myalgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neuromyasthenia. Am. J. Med. 1959, 26, 569–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, A.M.; Dowsett, E.G. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: Then and Now. In The Clinical and Scientific Basis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 1st ed.; Hyde, B.M., Goldstein, J., Levine, P., Eds.; The Nightingale Research Foundation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1992; pp. 569–595. ISBN 978-0969566205. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, G.P.; Kaplan, J.E.; Gantz, N.M.; Komaroff, A.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Straus, S.E.; Jones, J.F.; Dubois, R.E.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Pahwa, S.; et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome: A working case definition. Ann. Intern. Med. 1988, 108, 387–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Sunnquist, M.; Brown, A.; Evans, M.; Vernon, S.D.; Furst, J.; Simonis, V. Examining case definition criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis. Fatigue 2014, 2, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Hickie, I.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Wakefield, D.; Parker, G.; Straus, S.E.; Dale, J.; McCluskey, D.; Hinds, G.; Brickman, A.; et al. What is chronic fatigue syndrome? Heterogeneity within an international multicentre study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2001, 35, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, B.Z.; Shiraishi, Y.; Mears, C.J.; Binns, H.J.; Taylor, R. Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbraith, S.; Cameron, B.; Li, H.; Lau, D.; Vollmer-Conna, U.; Lloyd, A.R. Peripheral blood gene expression in postinfective fatigue syndrome following from three different triggering infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salit, I.E. Precipitating factors for the chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1997, 31, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyller, V.B. The chronic fatigue syndrome—An update. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2007, 115, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baschetti, R. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a form of Addison's disease. J. Intern. Med. 2000, 247, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twisk, F.N.M. The status of and future research into Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome: The need of accurate diagnosis, objective assessment, and acknowledging biological and clinical subgroups. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowsett, E.G. Myalgic encephalomyelitis, or what? Lancet 1988, 332, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twisk, F.N.M. Replacing Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome with systemic exercise intolerance disease is not the way forward. Diagnostics 2016, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Sunnquist, M.; Kot, B.; Brown, A. Unintended consequences of not specifying exclusionary illnesses for systemic exertion intolerance disease. Diagnostics 2015, 5, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacul, L.C.; Lacerda, E.M.; Pheby, D.; Campion, P.; Molokhia, M.; Fayyaz, S.; Leite, J.C.; Poland, F.; Howe, A.; Drachler, M.L.; et al. Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: A repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twisk, F.N.M. Accurate diagnosis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome based upon objective test methods for characteristic symptoms. World J. Methodol. 2015, 5, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, L.; Wood, L.; Behan, W.M.; Maclaren, W.M. Demonstration of delayed recovery from fatiguing exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur. J. Neurol. 1999, 6, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell, C.R.; Stevens, S.R.; Davenport, T.E.; Van Ness, J.M. Discriminative validity of metabolic and workload measurements for identifying people with chronic fatigue syndrome. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.B.; Light, A.R.; Light, K.C.; Broderick, G.; Shields, M.R.; Dougherty, R.J.; Meyer, J.D.; Van Riper, S.; Stegner, A.J.; Ellingson, L.D.; et al. Neural consequences of post-exertion malaise in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 62, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streeten, D.H. Role of impaired lower-limb venous innervation in the pathogenesis of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2001, 321, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocon, A.J.; Messer, Z.R.; Medow, M.S.; Stewart, J.M. Increasing orthostatic stress impairs neurocognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin. Sci. 2012, 122, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockshell, S.J.; Mathias, J.L. Cognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1253–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulheim, D.; Fagermoen, E.; Sivertsen, Ø.S.; Winger, A.; Wyller, V.B.; Øie, M.G. Cognitive dysfunction in adolescents with chronic fatigue: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, M.; Smith, A. An investigation into the cognitive deficits associated with chronic fatigue syndrome. Open Neurol. J. 2009, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, A.M. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Postviral Fatigue States: The Saga of Royal Free Disease, 2nd ed.; Gower Publishing Corporation: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Nakatomi, Y.; Mizuno, K.; Ishii, A.; Wada, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Tazawa, S.; Onoe, K.; Fukuda, S.; Kawabe, J.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Neuroinflammation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: An 11C-(R)-PK11195 PET study. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Meer, J.W.M.; Lloyd, A.R. A controversial consensus—Comment on article by Broderick et al. J. Intern. Med. 2012, 271, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ME (Ramsay) [1] | CFS (Fukuda) [2] | SEID (IOM/NAM) [3] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name and definition | 1957–1990 | 1994 (1988) | 2015 |

| Onset | Illness commonly initiated by respiratory and/or gastrointestinal infection, but an insidious or more dramatic onset following neurological, cardiac, or endocrine disability occurs. | Unspecified | Unspecified |

| Definition (distinctive symptoms) | Muscular symptoms, including prolonged postexertional muscle weakness (mandatory), myalgia, and muscle tenderness (often). Neurological symptoms, including cognitive impairment, day–night reversal, sensory dysfunction, and emotional lability. | Chronic fatigue (mandatory) and at least four of the following eight symptoms: Substantial impairment in short-term memory or concentration, a sore throat, tender lymph nodes, muscle pain, multijoint pain, headaches (of a new type, pattern, or severity), unrefreshing sleep, and postexertional “malaise”. | Chronic fatigue (not lifelong, not due to ongoing excessive exertion, and not alleviated by rest), postexertional “malaise”, unrefreshing sleep, and cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance. |

| Other common symptoms | Cardiovascular impairment, and Autonomic dysfunction |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Twisk, F.N.M. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease: Three Distinct Clinical Entities. Challenges 2018, 9, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe9010019

Twisk FNM. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease: Three Distinct Clinical Entities. Challenges. 2018; 9(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe9010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleTwisk, Frank N.M. 2018. "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease: Three Distinct Clinical Entities" Challenges 9, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe9010019