Susceptibility of CoFeB/AlOx/Co Magnetic Tunnel Junctions to Low-Frequency Alternating Current

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

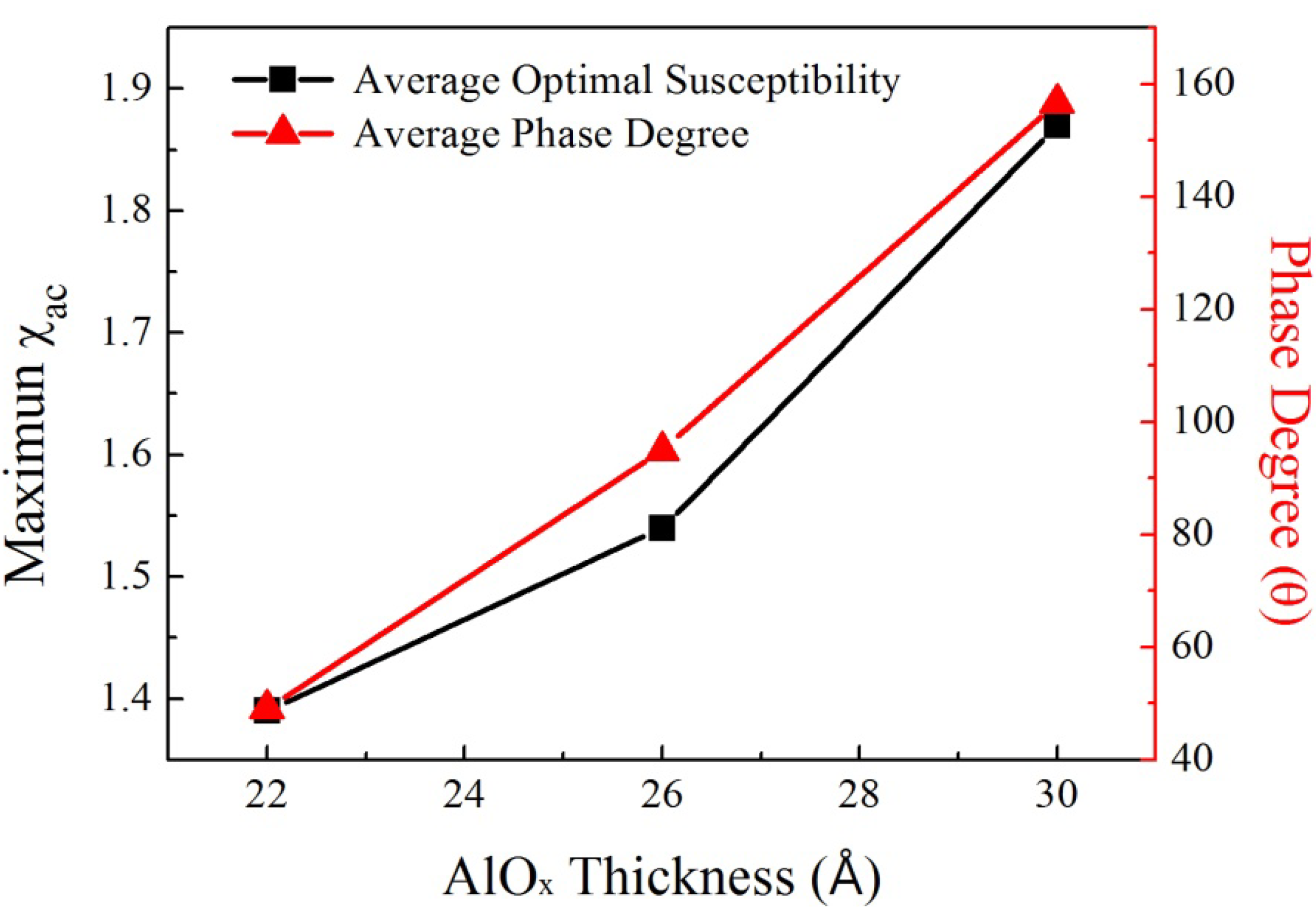

| d (Å) | Optimal susceptibility No. 1 | Optimal susceptibility No. 2 | Optimal susceptibility No. 3 | Average optimal susceptibility | Optimal resonance frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 1.9861 | 0.9452 | 0.6536 | 1.1950 | 500 Hz |

| 26 | 2.2841 | 1.1405 | 0.7594 | 1.3947 | 500 Hz |

| 30 | 2.4905 | 2.2711 | 0.8487 | 1.8700 | 500 Hz |

3. Experimental Section

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoffmann, F.; Stankoff, A.; Pascard, H. Evidence for an exchange coupling at the interface between two ferromagnetic films. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 41, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, D.; Siegmann, H.C.; Bagus, P.S.; Kay, E. Simple model for thin ferromagnetic films exchange coupled to an antiferromagnetic substrate. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 62, 3047–3049. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, B.; Tserkovnyak, Y.; Woltersdorf, G.; Brataas, A.; Urban, R.; Bauer, G.E.W. Dynamic exchange coupling in magnetic bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 187601–187604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Jen, S.U.; Yao, Y.D.; Wu, J.M.; Sun, A.C. Interfacial effects on magnetostriction of CoFeB/AlOx/Co junction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 222509:1–222509:3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Nordman, C.; Daughton, J.; Qian, Z.; Fink, J. 70% TMR at room temperature for SDT sandwich junctions with CoFeB as free and reference layers. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2004, 40, 2269–2271. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; Lum, W.H.; Sbiaa, R.; Lua, S.Y.H.; Tan, H.K. Annealing effects on CoFeB-MgO magnetic tunnel junctions with perpendicular anisotropy. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 039904:1–039904:4. [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama, T.; Ni, C.; Wang, W.G.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, J.Q. Tunneling magnetoresistance in (001)-oriented FeCo/MgO/FeCo magnetic tunneling junctions grown by sputtering deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 222503:1–222503:3. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.M.; Wang, Y.H.; Chen, W.C.; Yang, S.Y.; Shen, K.H.; Kao, M.J.; Tsai, M.J.; Kuo, C.Y.; Wu, J.C.; Horng, L. Repair effect on patterned CoFeB-based magnetic tunneling junction using rapid thermal annealing. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 310, 1920–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djayaprawira, D.D.; Tsunekawa, K.; Nagai, M.; Maehara, H.; Yamagata, S.; Watanabe, N.; Yuasa, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Ando, K. 230% room-temperature magnetoresistance in CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 092502:1–092502:3. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, J.; Ikeda, S.; Lee, Y.M.; Matsukura, F.; Ohno, H. Effect of high annealing temperature on giant tunnel magnetoresistance ratio of CoFeB/MgO/CoFeB magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 232510:1–232510:3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T.; Wu, J.W. Effect of tunneling barrier as spacer on exchange coupling of CoFeB/AlOx/Co trilayer structures. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 9246–9248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coïsson, M.; Tiberto, P.; Vinai, F.; Tyagi, P.V.; Modak, S.S.; Kane, S.N. Penetration depth and magnetic permeability calculations on GMI effect and comparison with measurements on CoFeB alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Ji, G.X.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, H.; Chang, Y.A. Epitaxial growth and surface roughness control of ferromagnetic thin films on Si by sputter deposition. J. Electron. Mater. 2008, 37, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharmouche, A.; Cherif, S.M.; Bourzami, A.; Layadi, A.; Schmerber, G. Structural and magnetic properties of evaporated Co/Si(100) and Co/glass thin films. J. Phys. D 2004, 37, 2583–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Chang, C.C. Effect of grain size on magnetic and nanomechanical properties of Co60Fe20B20 thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 498, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.G.; Laughlin, D.E. Effect of seed layers in improving the crystallographic texture of CoCrPt perpendicular recording media. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 91, 8076–8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Chang, Z.G. Low-frequency alternative-current magnetic susceptibility of amorphous and nanocrystalline Co60Fe20B20 films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 2224–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Chien, J.J.; Wang, W.C.; Yu, C.Y.; Hing, N.S.; Hong, H.E.; Hong, C.Y.; Yang, H.C.; Chang, C.F.; Lin, H.Y. Magnetic nanoparticles for high-sensitivity detection on nucleic acids via superconducting-quantum-interference-device-based immunomagnetic reduction assay. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2011, 323, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.-T.; Chang, Z.-G. Susceptibility of CoFeB/AlOx/Co Magnetic Tunnel Junctions to Low-Frequency Alternating Current. Nanomaterials 2013, 3, 574-582. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano3040574

Chen Y-T, Chang Z-G. Susceptibility of CoFeB/AlOx/Co Magnetic Tunnel Junctions to Low-Frequency Alternating Current. Nanomaterials. 2013; 3(4):574-582. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano3040574

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yuan-Tsung, and Zu-Gao Chang. 2013. "Susceptibility of CoFeB/AlOx/Co Magnetic Tunnel Junctions to Low-Frequency Alternating Current" Nanomaterials 3, no. 4: 574-582. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano3040574

APA StyleChen, Y.-T., & Chang, Z.-G. (2013). Susceptibility of CoFeB/AlOx/Co Magnetic Tunnel Junctions to Low-Frequency Alternating Current. Nanomaterials, 3(4), 574-582. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano3040574