TiO2 Films Modified with Au Nanoclusters as Self-Cleaning Surfaces under Visible Light

Abstract

:1. Introduction

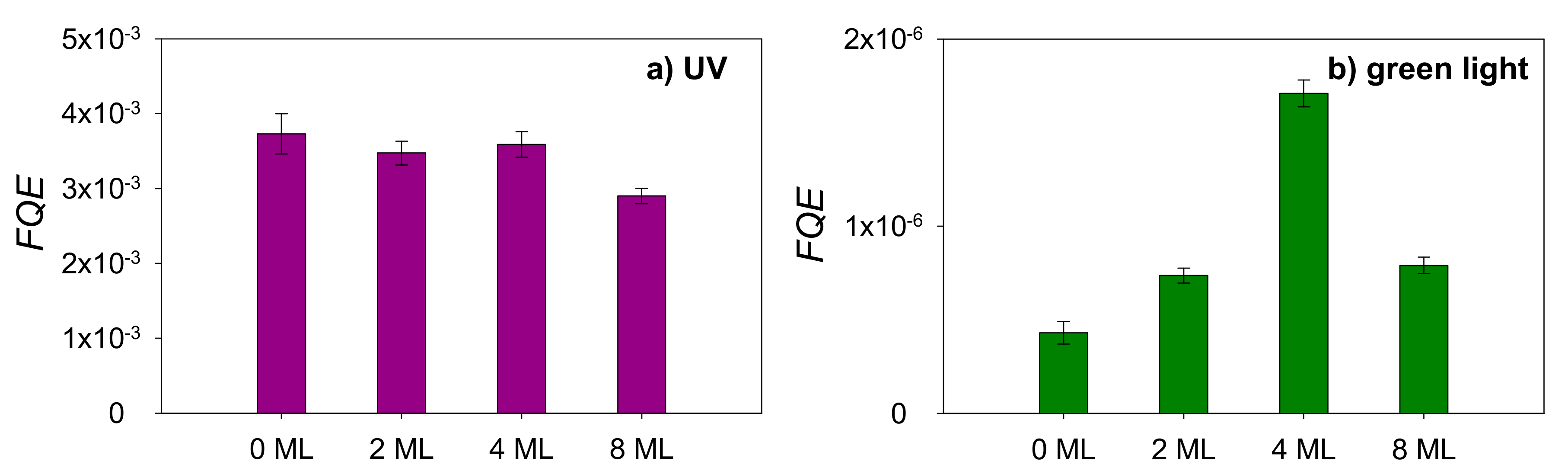

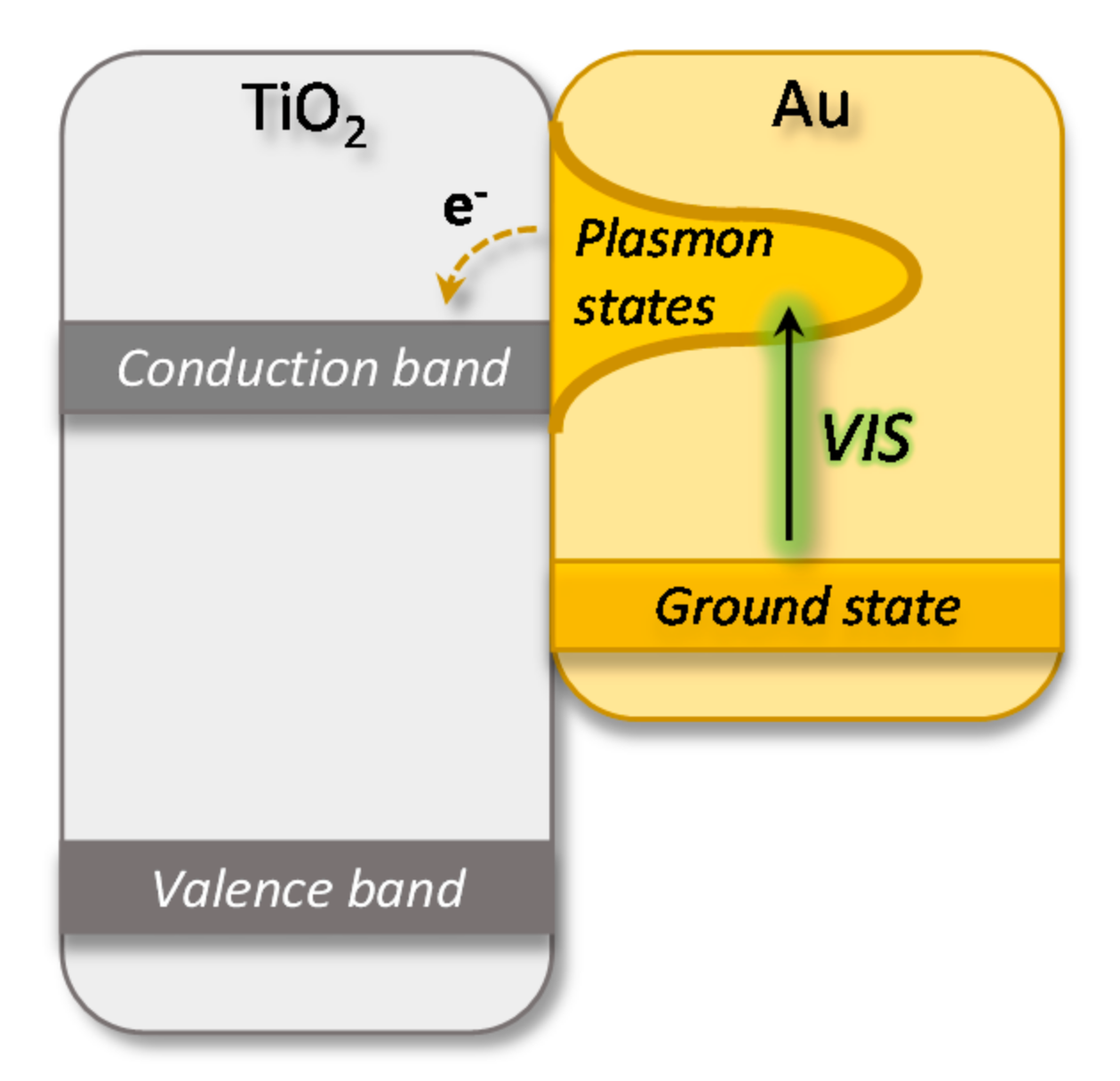

2. Results

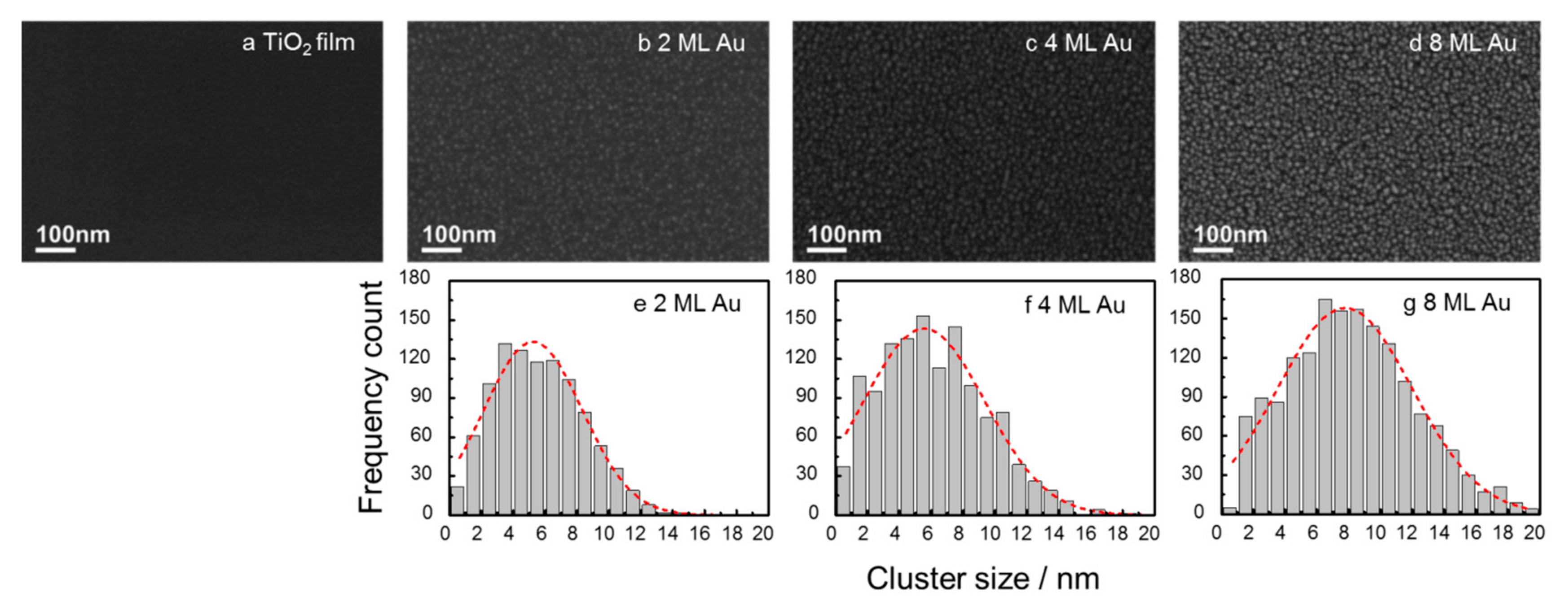

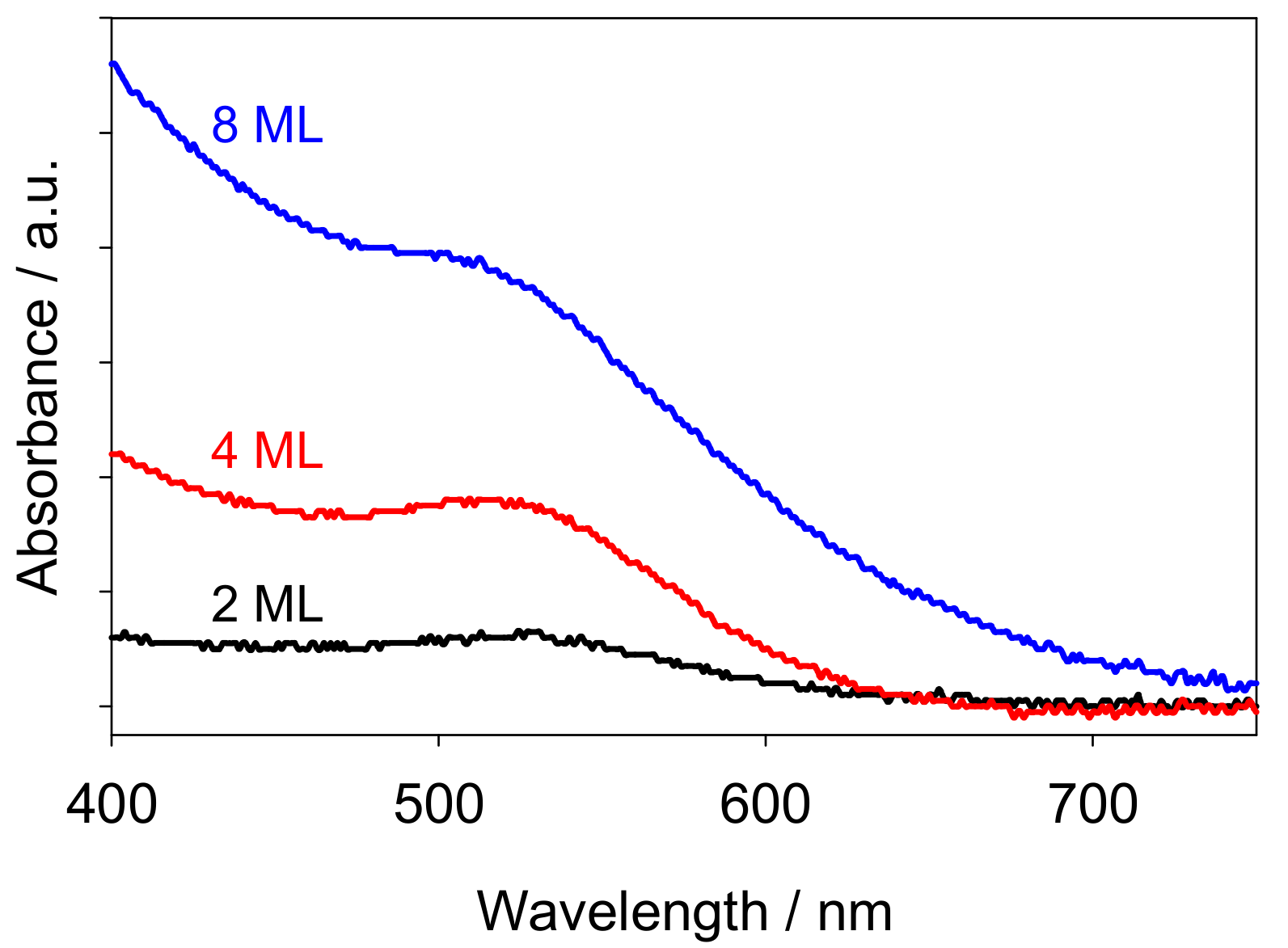

2.1. Morphology of Au Nanoclusters Modified Films

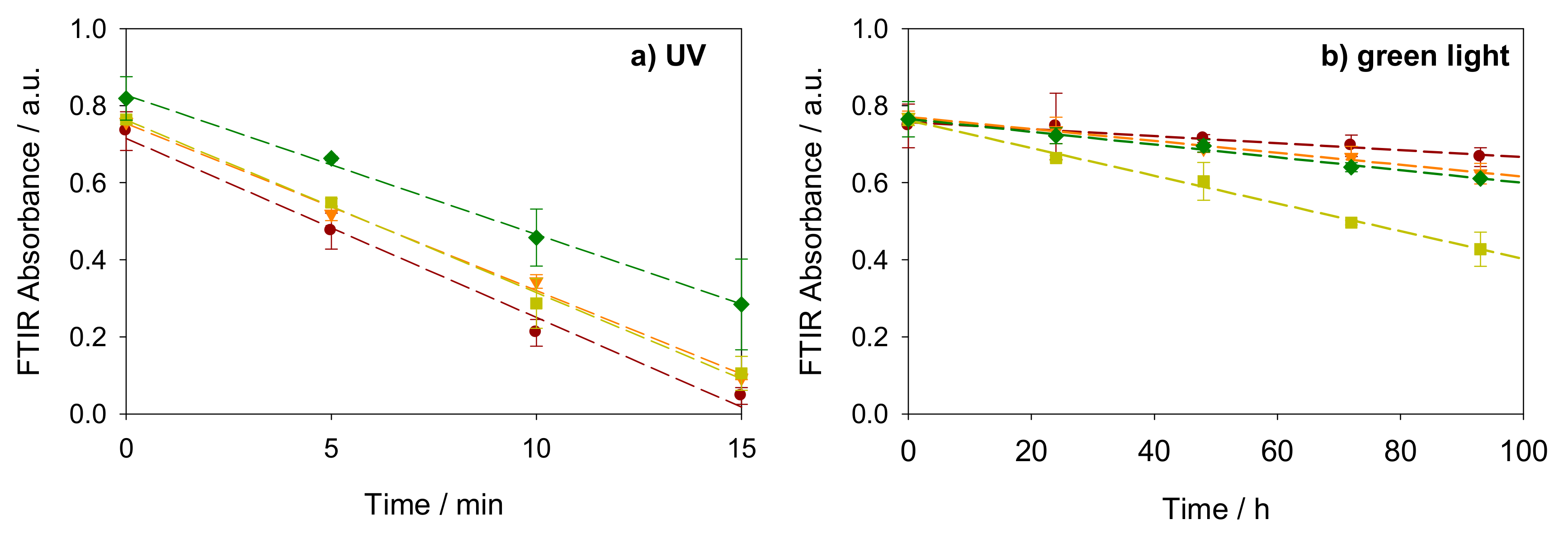

2.2. Photocatalysis on Stearic Acid

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Au Nanoclusters Modified Films

4.2. Film Characterization

4.3. Photocatalysis towards Stearic Acid Degradation

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mills, A.; LeHunte, S. An overview of semiconductor photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 1997, 108, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenderich, K.; Mul, G. Methods, mechanism, and applications of photodeposition in photocatalysis: A review. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14587–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.A.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Bannat, I.; Wark, M. Gold nanoparticles on mesoporous interparticle networks of titanium dioxide nanocrystals for enhanced photonic efficiencies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 7429–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Y.K.; Modi, G.; Cretu, V.; Postica, V.; Lupan, O.; Reimer, T.; Paulowicz, I.; Hrkac, V.; Benecke, W.; Kienle, L.; et al. Direct growth of freestanding ZnO tetrapod networks for multifunctional applications in photocatalysis, UV photodetection, and gas sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 2015, 7, 14303–14316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grottrup, J.; Schutt, F.; Smazna, D.; Lupan, O.; Adelung, R.; Mishra, Y.K. Porous ceramics based on hybrid inorganic tetrapodal networks for efficient photocatalysis and water purification. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 14915–14922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Y.K.; Adelung, R. ZnO tetrapod materials for functional applications. Mater. Today 2017. [CrossRef]

- Reimer, T.; Paulowicz, I.; Roder, R.; Kaps, S.; Lupan, O.; Chemnitz, S.; Benecke, W.; Ronning, C.; Adelung, R.; Mishra, Y.K. Single step integration of ZnO nano- and microneedles in Si trenches by novel flame transport approach: Whispering gallery modes and photocatalytic properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 2014, 6, 7806–7815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Kudo, A. Visible-light-response and photocatalytic activities of TiO2 and SrTiO3 photocatalysts codoped with antimony and chromium. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 5029–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivula, K.; Le Formal, F.; Gratzel, M. Solar water splitting: Progress using hematite (α-Fe2O3) photoelectrodes. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 432–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi, D.K.; Parida, K. Facile fabrication of alpha-FeOOH nanorod/RGO composite: A robust photocatalyst for reduction of Cr(VI) under visible light irradiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 10300–10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yu, J.G.; Guo, D.P.; Cui, C.; Ho, W.K. A hierarchical Z-scheme CdS-WO3 photocatalyst with enhanced CO2 reduction activity. Small 2015, 11, 5262–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Alamo, J.A. Nanometre-scale electronics with III-V compound semiconductors. Nature 2011, 479, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Navalon, S.; Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction by TiO2 and related titanium containing solids. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9217–9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, A.L.; Novoseltceva, E.; Louarn, E.; Beaunier, P.; Kowalska, E.; Ohtani, B.; Valenzuela, M.A.; Remita, H.; Colbeau-Justin, C. Synergetic effect of Ni and Au nanoparticles synthesized on titania particles for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 191, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, A.L.; Dragoe, D.; Wang, K.L.; Beaunier, P.; Kowalska, E.; Ohtani, B.; Uribe, D.B.; Valenzuela, M.A.; Remita, H.; Colbeau-Justin, C. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution using Ni-Pd/TiO2: Correlation of light absorption, charge-carrier dynamics, and quantum efficiency. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 14302–14311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, D.; Malato, S. Solar photocatalysis: A clean process for water detoxification. Sci. Total Environ. 2002, 291, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnen, J.; Kilvington, S.; Kehoe, S.C.; Al-Touati, F.; McGuigan, K.G. Solar and photocatalytic disinfection of protozoan, fungal and bacterial microbes in drinking water. Water Res. 2005, 39, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, M.; Cheng, M.Z.; Zhou, S.Q.; Wu, Q.S.; Wang, N.; Zhou, L.Y. Synthesis of reusable NiCo@Pt nanoalloys from icosahedrons to spheres by element lithography and their synergistic photocatalysis for nano-ZnO toward dye wastewater degradation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 11702–11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.X.; Xu, Z.T.; Wang, X.X.; Long, J.L.; Su, W.Y.; Fu, X.Z.; Lin, Q. Photocatalytic and antibacterial properties of medical-grade PVC material coated with TiO2 film. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B 2008, 87B, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, S.W. TiO2 photocatalysis for the degradation of pollutants in gas phase: From morphological design to plasmonic enhancement. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2015, 24, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.J.; Zhao, Q.N.; Yu, J.G.; Liu, B.S. Development of multifunctional photoactive self-cleaning glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2008, 354, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.T.; Wu, N.Q. Semiconductor-based photocatalysts and photoelectrochemical cells for solar fuel generation: A review. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 1360–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Irie, H.; Fujishima, A. TiO2 photocatalysis: A historical overview and future prospects. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Part 1 2005, 44, 8269–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, S.W.; Keulemans, M.; Goris, B.; Blommaerts, N.; Bals, S.; Martens, J.A.; Lenaerts, S. Plasmonic ‘rainbow’ photocatalyst with broadband solar light response for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 188, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, S.W.; Keulemans, M.; Filippousi, M.; Flahaut, D.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Lacombe, S.; Martens, J.A.; Lenaerts, S. Plasmonic gold-silver alloy on TiO2 photocatalysts with tunable visible light activity. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 156, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafizas, A.; Kellici, S.; Darr, J.A.; Parkin, I.P. Titanium dioxide and composite metal/metal oxide titania thin films on glass: A comparative study of photocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2009, 204, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Tahir, B.; Amin, N.A.S. Synergistic effect in plasmonic Au/Ag alloy NPs co-coated TiO2 NWs toward visible-light enhanced CO2 photoreduction to fuels. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 204, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, S.; Yamashita, S.; Abe, S.; Tsubota, T.; Ohno, T. Effect of core@shell (Au@Ag) nanostructure on surface plasmon-induced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 211, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowetz, M.; Villa, A.; Prati, L.; Selli, E. Effects of Au nanoparticles on TiO2 in the photocatalytic degradation of an azo dye. Gold Bull. 2007, 40, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, B.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Zhurkin, E.; Hou, M.; Verschoren, G.; Kuhn, L.T.; Bouwen, W.; Lievens, P. Transmission electron microscopy and Monte Carlo simulations of ordering in Au-Cu clusters produced in a laser vaporization source. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 165406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhenage, R.P.; Yan, H.; Tenney, S.A.; Park, N.; Henkelman, G.; Albrecht, P.; Mullins, D.R.; Chen, D.A. Understanding the nucleation and growth of metals on TiO2: Co compared to Au, Ni, and Pt. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7191–7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, T.; Lu, P.; Ichikawa, S.; Tanaka, K.; Haruta, M. Analytical TEM study on the dispersion of Au nanoparticles in Au/TiO2 catalyst prepared under various temperatures. Surf. Interface Anal. 2001, 31, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Wang, J.S. Simultaneous monitoring of the destruction of stearic acid and generation of carbon dioxide by self-cleaning semiconductor photocatalytic films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2006, 182, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, E.; Besson, S.; Durand, C.; Moreau, M.; Gacoin, T.; Boilot, J.P. Transparent mesoporous nanocomposite films for self-cleaning applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, S.W.; Masschaele, K.; Moortgat, E.; Korany, T.E.; Hauchecorne, B.; Martens, J.A.; Lenaerts, S. Factors driving the activity of commercial titanium dioxide powders towards gas phase photocatalytic oxidation of acetaldehyde. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 2311–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurum, D.C.; Agrios, A.G.; Gray, K.A.; Rajh, T.; Thurnauer, M.C. Explaining the enhanced photocatalytic activity of degussa p25 mixed-phase TiO2 using EPR. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 4545–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, M.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Nadeem, M.A.; Metson, J.B.; Keane, M.A.; Howe, R.F.; Llorca, J.; Idriss, H. The effect of gold loading and particle size on photocatalytic hydrogen production from ethanol over Au/TiO2 nanoparticles. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caretti, I.; Keulemans, M.; Verbruggen, S.W.; Lenaerts, S.; Van Doorslaer, S. Light-induced processes in plasmonic gold/TiO2 photocatalysts studied by electron paramagnetic resonance. Top. Catal. 2015, 58, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linic, S.; Christopher, P.; Ingram, D.B. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, J.B.; Karnahl, M.; Junge, H.; Beller, M.; Hollmann, D.; Bruckner, A. Water reduction with visible light: Synergy between optical transitions and electron transfer in Au-TiO2 catalysts visualized by in situ epr spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11420–11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, P.; Vanbuel, J.; Li, Y.; Liao, T.-W.; Janssens, E.; Lievens, P. The double-laser ablation source approach. In Gas-Phase Synthesis of Nanoparticles; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, Y.; Luo, Z.; Rabenberg, L.; Heller, A. Photooxidative self-cleaning transparent titanium-dioxide films on glass. J. Mater. Res. 1995, 10, 2842–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, T.-W.; Verbruggen, S.W.; Claes, N.; Yadav, A.; Grandjean, D.; Bals, S.; Lievens, P. TiO2 Films Modified with Au Nanoclusters as Self-Cleaning Surfaces under Visible Light. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8010030

Liao T-W, Verbruggen SW, Claes N, Yadav A, Grandjean D, Bals S, Lievens P. TiO2 Films Modified with Au Nanoclusters as Self-Cleaning Surfaces under Visible Light. Nanomaterials. 2018; 8(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Ting-Wei, Sammy W. Verbruggen, Nathalie Claes, Anupam Yadav, Didier Grandjean, Sara Bals, and Peter Lievens. 2018. "TiO2 Films Modified with Au Nanoclusters as Self-Cleaning Surfaces under Visible Light" Nanomaterials 8, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8010030

APA StyleLiao, T.-W., Verbruggen, S. W., Claes, N., Yadav, A., Grandjean, D., Bals, S., & Lievens, P. (2018). TiO2 Films Modified with Au Nanoclusters as Self-Cleaning Surfaces under Visible Light. Nanomaterials, 8(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8010030