Looking for the Phase Transition—Recent NA61/SHINE Results

Abstract

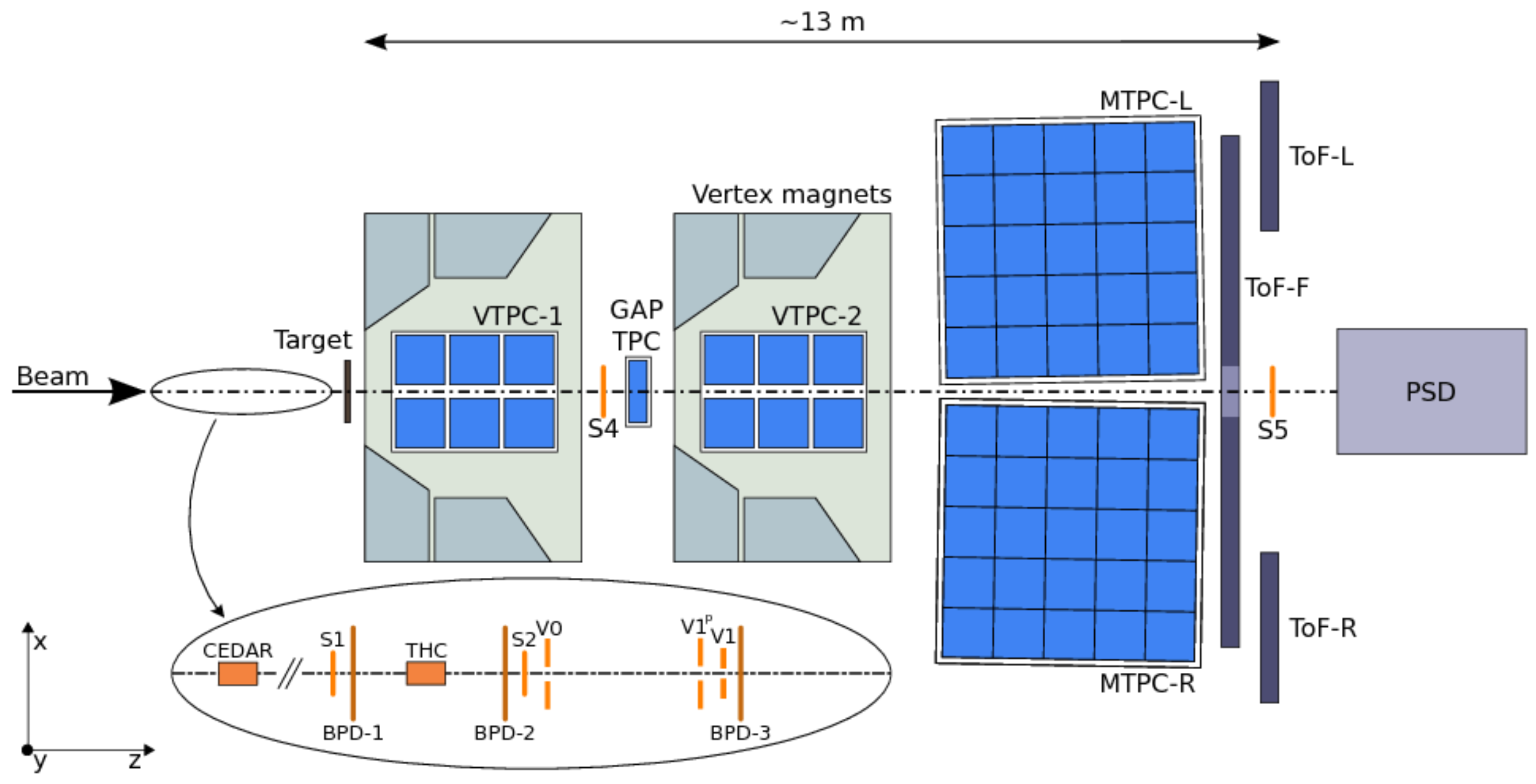

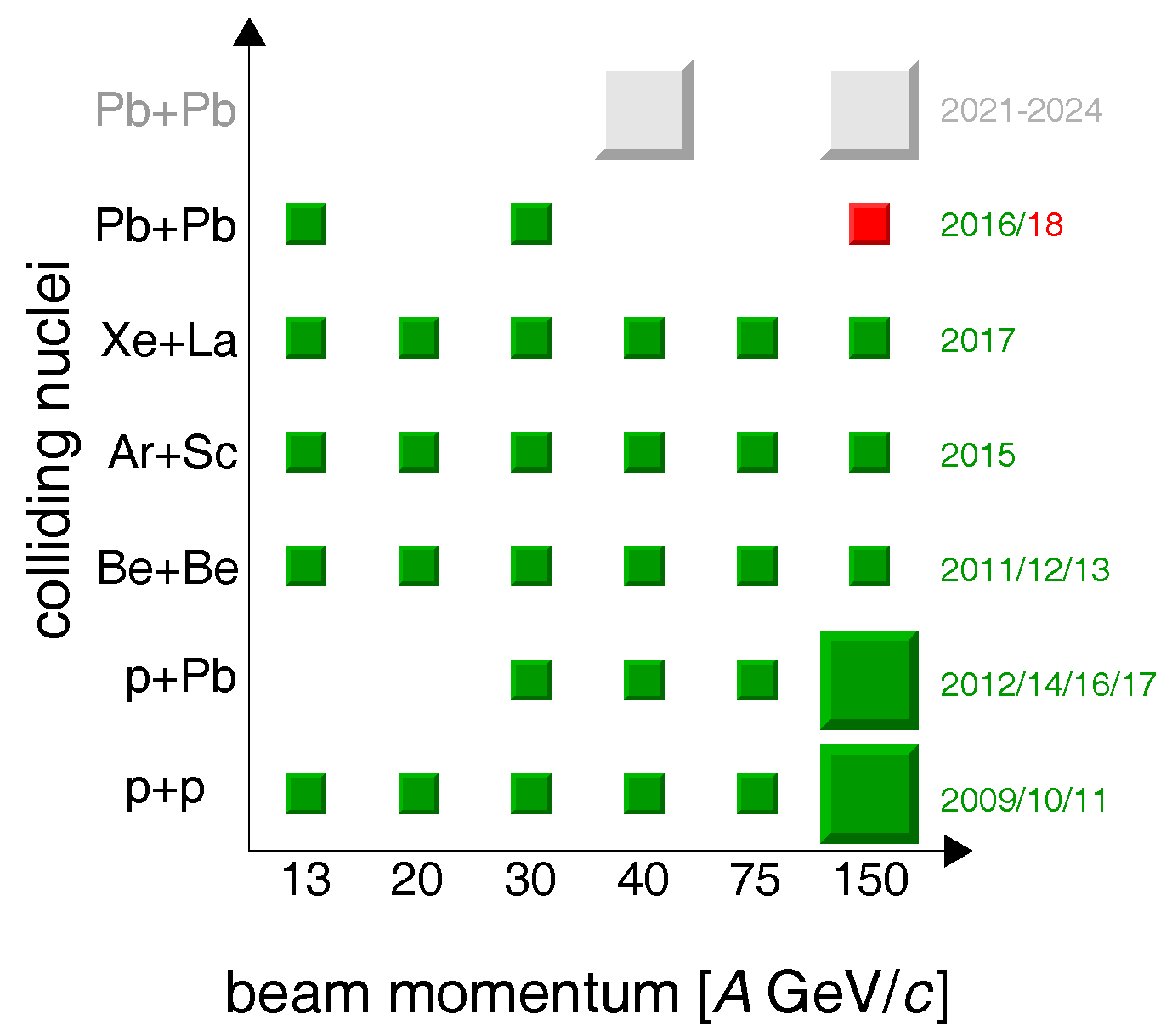

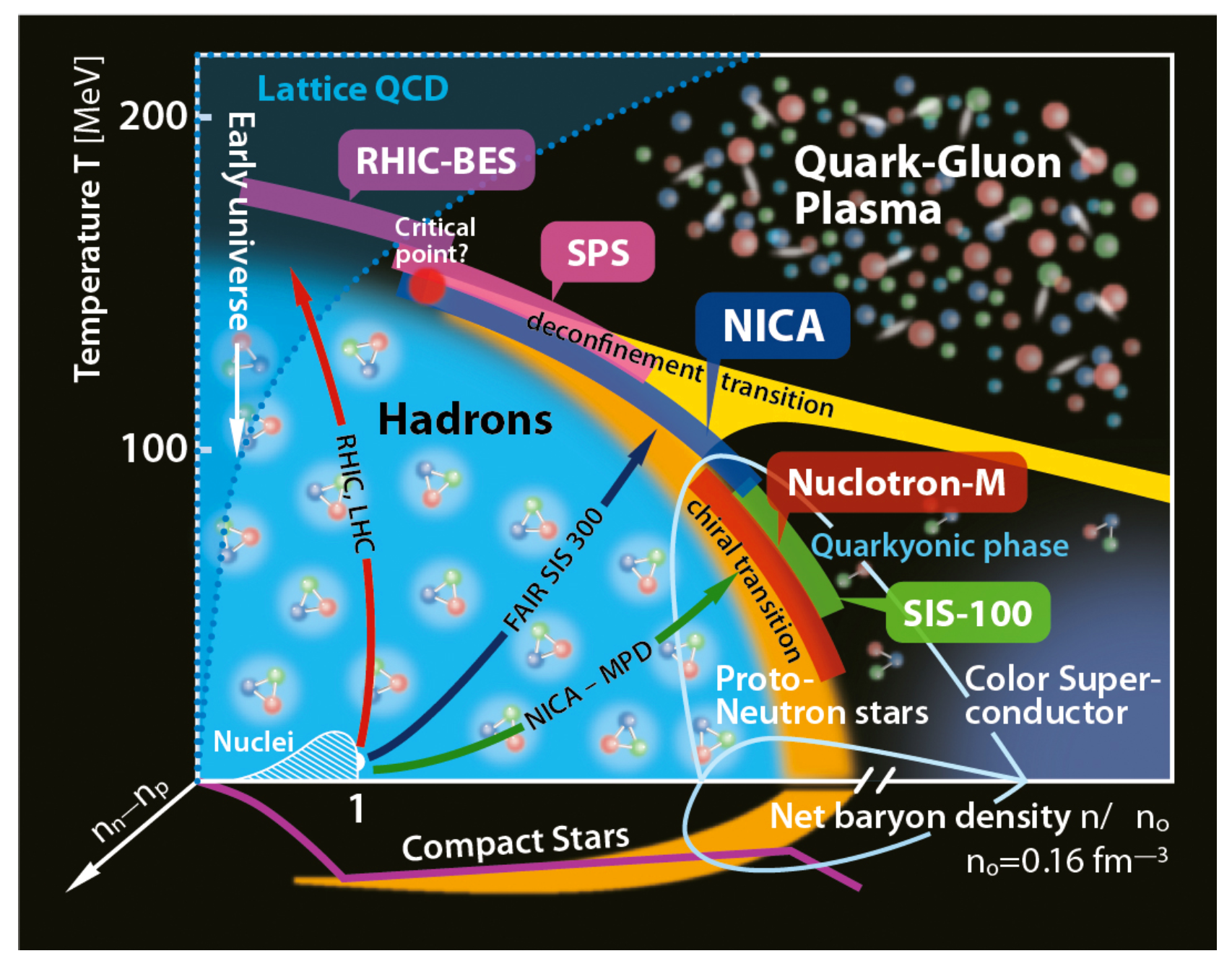

:1. Introduction

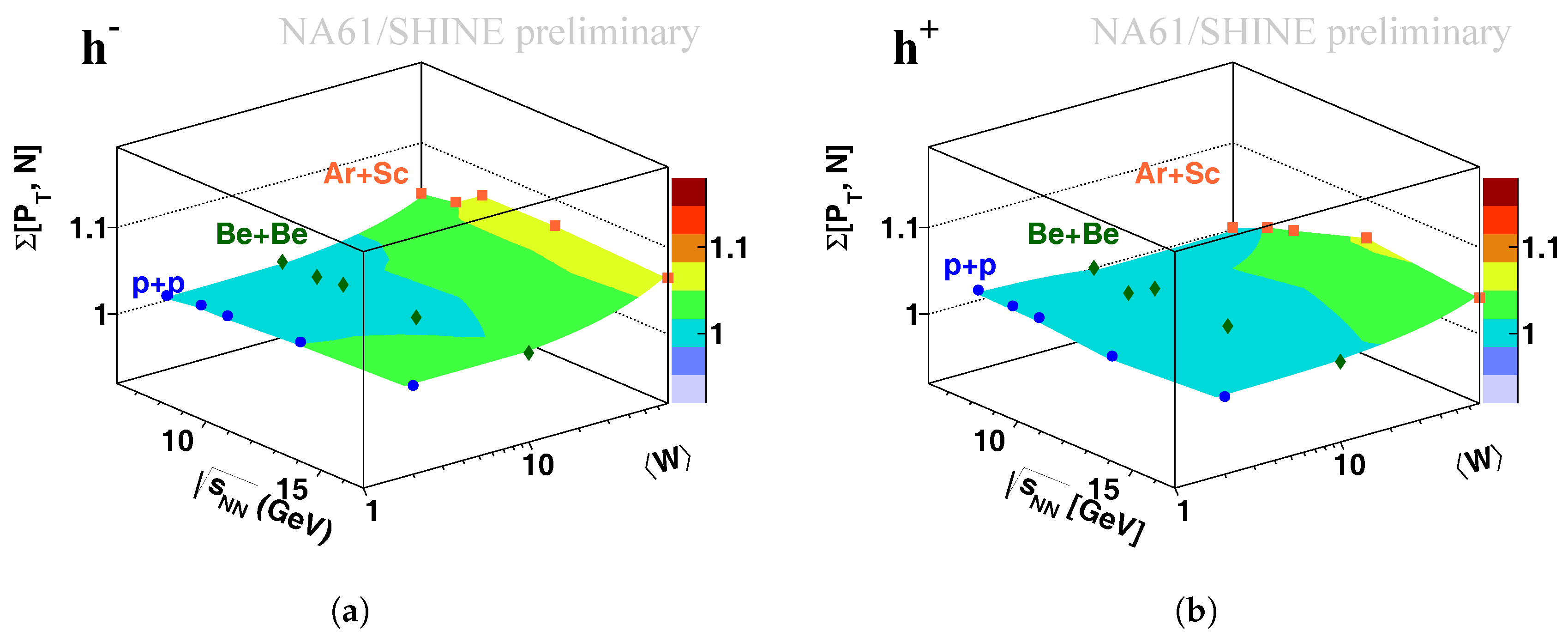

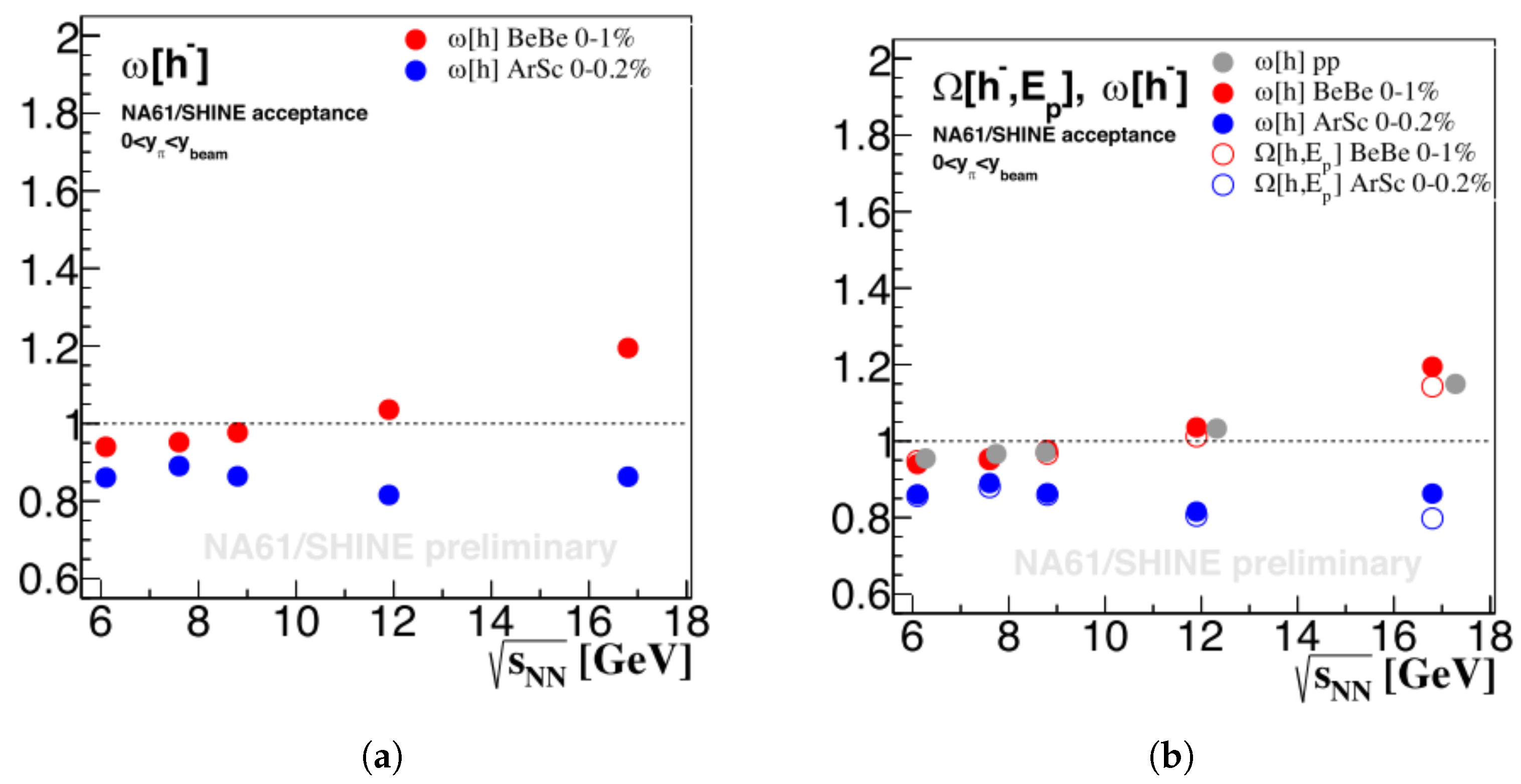

2. New NA61/SHINE Results

2.1. Irregularities—The Horn

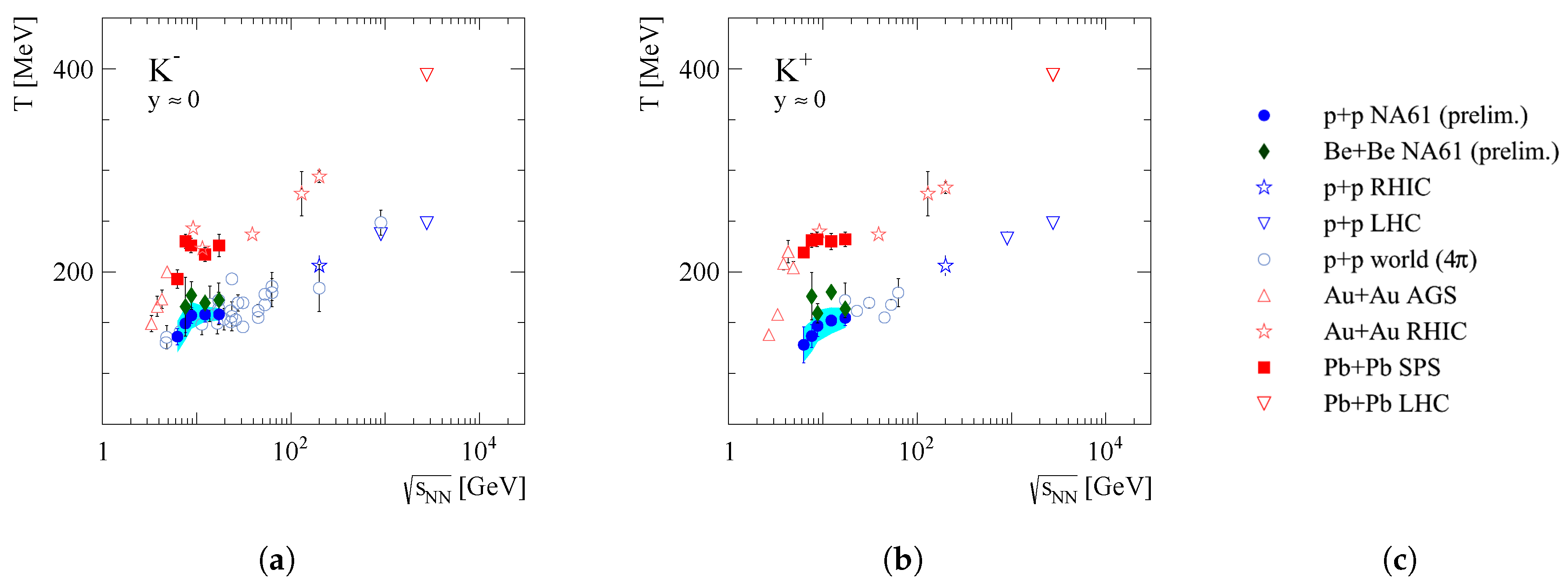

2.2. Irregularities—The Step

2.3. Fluctuations

3. System Size Dependence

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGS | Argonne National Laboratory |

| CERN | Conseil Europén pour la Recherche Nucléaire |

| CR | critical point |

| HG | hadron gas |

| J-PARC | Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex |

| LHC | Large Hadron Collider |

| HIC | heavy ion collision |

| QCD | quantum chromodynamics |

| QGP | quark-gluon plasma |

| RHIC | Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider |

| SPS | Super Proton Synchrotron |

References

- Antoniou, N.; et al. [NA49-future Collaboration]; Study of Hadron Production in Hadron Nucleus and Nucleus Nucleus Collisions at the CERN SPS; CERN-SPSC-2006-034; CERN: Genève, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abgrall, N.; et al. [NA61/SHINE Collaboration]; Calibration and Analysis of the 2007 Data; CERN-SPSC- 2008-018; CERN: Genève, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abgrall, N.; et al. [NA61/SHINE Collaboration]. Measurements of Cross Sections and Charged Pion Spectra in Proton-Carbon Interactions at 31 GeV/c. Phys. Rev. C 2011, 84, 034604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; et al. [Pierre Auger Collaboration]. Properties and performance of the prototype instrument for the Pierre Auger Observatory. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2004, 523, 50–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, T.; et al. [KASCADE Collaboration]. The cosmic-ray experiment KASCADE. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2003, 513, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morison, I. Introduction to Astronomy and Cosmology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-470-03333-3. [Google Scholar]

- Satz, H. Ultimate Horizons. Probing the Limits of the Universe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 1612-3018. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T.; Bastian, N.U.F.; Wu, M.R.; Typel, S.; Klähn, T.; Blaschke, D.B. High-density phase transition paves the way for supernova explosions of massive blue-supergiant stars. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1712.08788. [Google Scholar]

- Benic, S.; Blaschke, D.; Alvarez-Castillo, D.E.; Fischer, T.; Typel, S. A new quark-hadron hybrid equation of state for astrophysics—I. High-mass twin compact stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2015, 577, A40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barducci, A.; Casalbuoni, R.; De Curtis, S.; Gatto, R.; Pettini, G. Chiral Symmetry Breaking in QCD at Finite Temperature and Density. Phys. Lett. B 1989, 231, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasz, A.M.; Jackson, A.D.; Shrock, R.E.; Stephanov, M.A.; Verbaarschot, J.J.M. Phase diagram of QCD. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 58, 096007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berges, J.; Rajagopal, K. Color superconductivity and chiral symmetry restoration at nonzero baryon density and temperature. Nucl. Phys. B 1999, 538, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Forcrand, P.; Philipsen, O. The Chiral critical point of Nf = 3 QCD at finite density to the order (μ/T)4. J. High Energy Phys. 2008, 2008(11), 012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazavov, A.; et al. [HotQCD Collaboration]. Equation of state in ( 2+1 )-flavor QCD. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 094503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazavov, A.; Ding, H.-T.; Hegde, P.; Kaczmarek, O.; Karsch, F.; Laermann, E.; Maezawa, Y.; Ohno, H.; Petreczky, P.H.; Wagner, M.; et al. The QCD Equation of State to from Lattice QCD. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 054504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caines, H. The Search for Critical Behavior and Other Features of the QCD Phase Diagram–Current Status and Future Prospects. Nucl. Phys. A 2017, 967, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Cosmic Separation of Phases. Phys. Rev. D 1984, 30, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromerth, M.J.; Rafelski, J. Hadronization of the quark Universe. arXiv, 2002; arXiv:astro-ph/0211346. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckel, T.; Schaffner-Bielich, J. A little inflation in the early universe at the QCD phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 041301, Erratum in 2011, 106, 069901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, B. The Trajectory of the Cosmic Plasma Through the Quark Matter Phase Diagram. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 043544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdzicki, M.; Gorenstein, M.I. On the Early Stage of Nucleus–Nucleus Collisions. Acta Phys. Polon. B 1999, 30, 2705. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, M.P. [NA61/SHINE Collaboration]. Identified kaon production in Ar+Sc collisions at SPS energies. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1712.02417. [Google Scholar]

- Alt, C.; et al. [NA49 Collaboration]. Pion and kaon production in central Pb+Pb collisions at 20A and 30A GeV: Evidence for the onset of deconfinement. Phys. Rev. C 2008, 77, 024903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdzicki, M. [NA49 Collaboration]. Report from NA49. J. Phys. G 2004, 30, S701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduszkiewicz, A. [NA61/SHINE Collaboration]. Recent results from NA61/SHINE. Nucl. Phys. A 2017, 967, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seryakov, A. [NA61/SHINE Collaboration]. Rapid change of multiplicity fluctuations in system size dependence at SPS energies. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1712.03014. [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzicki, M. [NA61/SHINE Collaboration]. Fluctuations and correlations from NA61/SHINE. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1801.00178. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turko, L. Looking for the Phase Transition—Recent NA61/SHINE Results. Universe 2018, 4, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe4030052

Turko L. Looking for the Phase Transition—Recent NA61/SHINE Results. Universe. 2018; 4(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe4030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurko, Ludwik. 2018. "Looking for the Phase Transition—Recent NA61/SHINE Results" Universe 4, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe4030052